Abstract

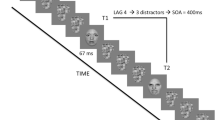

Mindfulness improves attentional control and regulates emotion. In the current study, two experiments were conducted to examine the role of sustained mindfulness practice in attentional capture by emotional distractors in different perceptual load conditions. Individuals with previous experience in mindfulness meditation and those without meditation experience participated. Participants were required to identify and respond to a target letter in a visual search task in high and low perceptual load conditions. They were instructed to ignore the distractors (Experiment 1: happy or angry faces; Experiment 2: pleasurable or unpleasurable IAPS images), which were present in 25% of total trials. Results indicated that distractors with positive emotional information captured the attention and interfered with the task performance of non-meditators in the high-load condition. However, mindfulness meditators reduced the interference from positive emotional information in the high-load condition. Moreover, mindfulness meditators processed negative emotional distractors more than non-meditators without compromising the visual-search performance in the high-load condition. Given that processing negative emotion requires more attentional resources than processing positive emotion, it may show that mindfulness meditators have more attentional resources. Additionally, those who practiced mindfulness meditation reported greater psychological well-being and fewer depressive symptoms. The findings suggest that mindfulness might improve attentional control for positive and pleasurable distractors. It reflects a diminished need in meditators to seek satisfaction from external pleasurable distractions. The findings have practical implications for managing hedonic compulsive behaviors and theoretical implications for understanding the interactive role of emotion and attention in mindfulness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Notes

Attentional capture refers to a momentary shift of attention when an unexpected or infrequent object is presented, even when subjects are unaware of the stimulus. Experimental studies of attentional capture (more specifically, implicit capture of attention) often index a change in performance on the primary task, e.g., an increase in reaction time, distractor interference score or a decrease in accuracy (Forster & Lavie, 2008a; Simons, 2000).

Of the total 18 participants excluded from Experiment 1 of the present study, three participants were left-handed (1 MM, 2 NM), and two explicitly reported being distracted by the external environment (1 MM, 1 NM). One participant attempted the study twice (1 NM); data from the first attempt could not be considered for analysis as the participant completed only the experiment (letter search task) on the first attempt and left the questionnaire unfilled. Two participants were removed because they could not understand the task properly (2 MM), which they mentioned in their feedback. Two more participants’ overall reaction time data showed high variability, indicating either anticipatory or slow responding (1 MM, 1 NM). Eight participants had high error rates (M > 25%; 6 MM, 2 NM), which might mean the failure to understand the task correctly or an inability to pay attention to the task (Gupta et al., 2016). We recognize that the high number of exclusions could be due to the use of an online platform where the external distractions increased, and control and understanding of the task decreased. Even with such a high number, the participants in the final analysis were well within the required sample size indicated by the G-Power analysis. NM = non-meditator, MM = mindfulness meditator.

To test if the results of the two experiments suggested an actual reduction in emotional interference in the mindfulness meditator group and not just a speed-accuracy trade-off strategy adopted by the group, an index of distraction was generated for accuracy similar to DI for reaction time. Accuracy for emotional stimuli was subtracted from accuracy for no-distractor condition. The results of three-way mixed ANOVA did not reveal any group differences in Experiment 1 (F(1,67) = 0.002, p = 0.96) and Experiment 2 (F(1,65) = 0.007, p = 0.93).

There was an apparent gender disparity between both groups, with more females in the mindfulness meditator group and more males in the non-meditator group participating in the study. Hence, further statistical analysis was applied to the final sample in each experiment to test whether the gender differences affected the distractor interference results. A four-way mixed ANOVA was performed on DI using load (high, low) and distractor condition (positive, negative) as within-group factors and group (mindfulness meditator, non-meditator) and gender (male, female) as between-group factors. There was no main effect of gender, and gender did not interact with any other variable in Experiment 1 (p > 0.07, for all) and Experiment 2 (p > 0.08, for all).

References

Baer, R. A. (Ed.). (2015). Mindfulness-based treatment approaches: Clinician's guide to evidence base and applications. Elsevier.

Baijal, S., & Gupta, R. (2008). Meditation-based training: a possible intervention for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Psychiatry (edgmont), 5(4), 48–55. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19727310%0A. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=PMC2719552

Bailey, N. W., Freedman, G., Raj, K., Sullivan, C. M., Rogasch, N. C., Chung, S. W., Hoy, K. E., Chambers, R., Hassed, C., Van Dam, N. T., Koenig, T., & Fitzgerald, P. B. (2019). Mindfulness meditators show altered distributions of early and late neural activity markers of attention in a response inhibition task. PLoS ONE, 14(8), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0203096

Bishop, S. R., Lau, M., Shapiro, S., Carlson, L., Anderson, N. D., Carmody, J., Segal, Z. V., Abbey, S., Speca, M., Velting, D., & Devins, G. (2004). Mindfulness: A proposed operational definition. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 11(3), 230–241. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy/bph077

Bodhi, B. (2011). What does mindfulness really mean? A Canonical Perspective. Contemporary Buddhism, 12(1), 19–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/14639947.2011.564813

Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(4), 822–848. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822

Cairncross, M., & Miller, C. J. (2020). The effectiveness of mindfulness-based therapies for ADHD: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Attention Disorders, 24(5), 627–643. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054715625301

Calvo, M. G., Gutiérrez-García, A., & Del Líbano, M. (2015). Sensitivity to emotional scene content outside the focus of attention. Acta Psychologica, 161, 36–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2015.08.002

Carretié, L. (2014). Exogenous (automatic) attention to emotional stimuli: A review. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 14(4), 1228–1258. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13415-014-0270-2

Chambers, R., Gullone, E., & Allen, N. B. (2009). Mindful emotion regulation: An integrative review. Clinical Psychology Review, 29(6), 560–572. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2009.06.005

Chambers, R., Lo, B. C. Y., & Allen, N. B. (2008). The impact of intensive mindfulness training on attentional control, cognitive style, and affect. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 32(3), 303–322. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-007-9119-0

Chan, D., & Woollacott, M. (2007). Effects of level of meditation experience on attentional focus: Is the efficiency of executive or orientation networks improved? Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 13(6), 651–657. https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2007.7022

Chiesa, A., Calati, R., & Serretti, A. (2011). Does mindfulness training improve cognitive abilities? A systematic review of neuropsychological findings. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(3), 449–464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.11.003

Chiesa, A., Serretti, A., & Jakobsen, J. C. (2013). Mindfulness: Top-down or bottom-up emotion regulation strategy? Clinical Psychology Review, 33(1), 82–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2012.10.006

Christopher, M. S., Neuser, N. J., Michael, P. G., & Baitmangalkar, A. (2012). Exploring the psychometric properties of the five facet mindfulness questionnaire. Mindfulness, 3(2), 124–131. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-011-0086-x

Cisler, J. M., Olatunji, B. O., Feldner, M. T., & Forsyth, J. P. (2010). Emotion regulation and the anxiety disorders: An integrative review. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 32(1), 68–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-009-9161-1

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis (pp. 18–74). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Compton, R. J. (2003). The interface between emotion and attention: A review of evidence from psychology and neuroscience. Behavioral and Cognitive Neuroscience Reviews, 2(2), 115–129. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534582303255278

Creswell, J. D. (2017). Mindfulness interventions. Annual Review of Psychology, 68(September), 491–516. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-042716-051139

Desbordes, G., Gard, T., Hoge, E. A., Hölzel, B. K., Kerr, C., Lazar, S. W., Olendzki, A., & Vago, D. R. (2015). Moving beyond mindfulness: Defining equanimity as an outcome measure in meditation and contemplative research. Mindfulness, 6(2), 356–372. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-013-0269-8

Eltiti, S., Wallace, D., & Fox, E. (2005). Selective target processing: Perceptual load or distractor salience? Perception and Psychophysics, 67, 876–885. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193540

Erthal, F. S., De Oliveira, L., Mocaiber, I., Pereira, M. G., Machado-Pinheiro, W., Volchan, E., & Pessoa, L. (2005). Load-dependent modulation of affective picture processing. Cognitive, Affective and Behavioral Neuroscience, 5(4), 388–395. https://doi.org/10.3758/CABN.5.4.388

Farb, N. A. S., Anderson, A. K., Irving, J. A., & Segal, Z. V. (2014). Mindfulness interventions and emotion regulation. In J. J. Gross (Ed.), Handbook of emotion regulation (pp. 548–567). The Guilford Press.

Forster, S., & Lavie, N. (2008a). Attentional capture by entirely irrelevant distractors. Visual Cognition, 16(2–3), 200–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/13506280701465049

Forster, S., & Lavie, N. (2008b). Failures to ignore entirely irrelevant distractors: The role of load. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 14(1), 73–83. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-898X.14.1.73

Garland, E. L., Farb, N. A., Goldin, P. R., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2015). Mindfulness broadens awareness and builds eudaimonic meaning: A process model of mindful positive emotion regulation. Psychological Inquiry, 26(4), 293–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/1047840X.2015.1064294

Garland, E. L., & Howard, M. O. (2018). Mindfulness-based treatment of addiction: Current state of the field and envisioning the next wave of research. Addiction Science and Clinical Practice, 13(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13722-018-0115-3

Guendelman, S., Medeiros, S., & Rampes, H. (2017). Mindfulness and emotion regulation: Insights from neurobiological, psychological, and clinical studies. Frontiers in Psychology, 220. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00220

Gupta, R. (2011). Attentional, visual, and emotional mechanisms of face processing proficiency in Williams syndrome. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 5, 18.

Gupta, R. (2019). Positive emotions have a unique capacity to capture attention. Progress in Brain Research, 247, 23–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.pbr.2019.02.001

Gupta, R., & Deák, G. O. (2015). Disarming smiles: Irrelevant happy faces slow post-error responses. Cognitive Processing, 16(4), 427–434.

Gupta, R., Hur, Y. J., & Lavie, N. (2016). Distracted by pleasure: Effects of positive versus negative valence on emotional capture under load. Emotion, 16(3), 328–337. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000112

Gupta, R., & Singh, J. P. (2021). Only irrelevant angry, but not happy, expressions facilitate the response inhibition. Attention, Perception, and Psychophysics, 83(1), 114–121. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13414-020-02186-w

Gupta, R., & Srinivasan, N. (2015). Only irrelevant sad but not happy faces are inhibited under high perceptual load. Cognition and Emotion, 29(4), 747–754. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2014.933735

Hölzel, B. K., Lazar, S. W., Gard, T., Schuman-Olivier, Z., Vago, D. R., & Ott, U. (2011). How does mindfulness meditation work? Proposing mechanisms of action from a conceptual and neural perspective. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6(6), 537–559. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691611419671

Isbel, B., & Summers, M. J. (2017). Distinguishing the cognitive processes of mindfulness: Developing a standardised mindfulness technique for use in longitudinal randomised control trials. Consciousness and Cognition, 52(May 2016), 75–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2017.04.019

Jha, A. P., Krompinger, J., & Baime, M. J. (2007). Mindfulness training modifies subsystems of attention. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 7(2), 109–119. https://doi.org/10.3758/CABN.7.2.109

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1990). Full catastrophe living: The program of the stress reduction clinic at the University of Massachusetts Medical Center. Delta.

Kanfer, R., Ackerman, P. L., Murtha, T. C., Dugdale, B., & Nelson, L. (1994). Goal setting, conditions of practice, and task performance: A resource allocation perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 79(6), 826–835. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.79.6.826

Katterman, S. N., Kleinman, B. M., Hood, M. M., Nackers, L. M., & Corsica, J. A. (2014). Mindfulness meditation as an intervention for binge eating, emotional eating, and weight loss: A systematic review. Eating Behaviors, 15(2), 197–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2014.01.005

Koob, G. F., & Volkow, N. D. (2016). Neurobiology of addiction: A neurocircuitry analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry, 3(8), 760–773. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(16)00104-8

Kozasa, E. H., Sato, J. R., Lacerda, S. S., Barreiros, M. A. M., Radvany, J., Russell, T. A., Sanches, L. G., Mello, L. E. A. M., & Amaro, E. (2012). Meditation training increases brain efficiency in an attention task. NeuroImage, 59(1), 745–749. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.06.088

Kral, T. R. A., Schuyler, B. S., Mumford, J. A., Rosenkranz, M. A., Lutz, A., & Davidson, R. J. (2018). Impact of short- and long-term mindfulness meditation training on amygdala reactivity to emotional stimuli. NeuroImage, 181(July), 301–313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.07.013

Kramer, R. S. S., Weger, U. W., & Sharma, D. (2013). The effect of mindfulness meditation on time perception. Consciousness and Cognition, 22(3), 846–852. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2013.05.008

Kuo, C. Y., & Yeh, Y. Y. (2015). Reset a task set after five minutes of mindfulness practice. Consciousness and Cognition, 35(1), 98–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2015.04.023

Lang, P. J., Bradley, M. M., & Cuthbert, B. N. (2008). International affective picture system (IAPS): Affective ratings of pictures and instruction manual. University of Florida, Center for Research in Psychophysiology.

Lavie, N. (2010). Attention, distraction, and cognitive control under load. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 19(3), 143–148. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721410370295

Lavie, N., Hirst, A., De Fockert, J. W., & Viding, E. (2004). Load theory of selective attention and cognitive control. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 133(3), 339–354. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-3445.133.3.339

Levinson, D. B., Stoll, E. L., Kindy, S. D., Merry, H. L., & Davidson, R. J. (2014). A mind you can count on: Validating breath counting as a behavioral measure of mindfulness. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 1202. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01202

Lichtenstein-Vidne, L., Henik, A., & Safadi, Z. (2012). Task relevance modulates processing of distracting emotional stimuli. Cognition and Emotion, 26(1), 42–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2011.567055

Lin, Y., Tang, R., & Braver, T. S. (2022). Investigating mindfulness influences on cognitive function: On the promise and potential of converging research strategies. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review, 29(4), 1198–1222. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-021-02008-6

Lodha, S., & S., Gupta, R. (2020). Book review: Stress Less, Accomplish More: Meditation for Extraordinary Performance. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1830.

Lodha, S., & Gupta, R. (2022). Mindfulness, Attentional Networks, and Executive Functioning: A Review of Interventions and Long-Term Meditation Practice. Journal of Cognitive Enhancement, 6(4), 531–548. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41465-022-00254-7

Lodha, S., & Gupta, R. (2023). Irrelevant angry, but not happy, faces facilitate response inhibition in mindfulness meditators. Current Psychology, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04384-9

Lovibond, P. F., & Lovibond, S. H. (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33(3), 335–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-U

Lundqvist, D., Flykt, A., & Öhman, A. (1998). The Karolinska directed emotional faces (KDEF). CD ROM from Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Psychology section, Karolinska Institutet, 91(630), 2–2. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/t27732-000

Lutz, A., Slagter, H. A., Dunne, J. D., & Davidson, R. J. (2008). Attention regulation and monitoring in meditation. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 12(4), 163–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2008.01.005

Magalhaes, A. A., Oliveira, L., Pereira, M. G., & Menezes, C. B. (2018). Does meditation alter brain responses to negative stimuli? A systematic review. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 12(November). https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2018.00448

Menezes, C. B., De Paula Couto, M. C., Buratto, L. G., Erthal, F., Pereira, M. G., & Bizarro, L. (2013). The improvement of emotion and attention regulation after a 6-week training of focused meditation: A randomized controlled trial. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/984678

Most, S. B., Smith, S. D., Cooter, A. B., Levy, B. N., & Zald, D. H. (2007). The naked truth: Positive, arousing distractors impair rapid target perception. Cognition and Emotion, 21(5), 964–981. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930600959340

Okon-Singer, H., Hendler, T., Pessoa, L., & Shackman, A. J. (2015). The neurobiology of emotion-cognition interactions: Fundamental questions and strategies for future research. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 9(FEB), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2015.00058

Okon-Singer, H., Tzelgov, J., & Henik, A. (2007). Distinguishing between automaticity and attention in the processing of emotionally significant stimuli. Emotion, 7(1), 147–157. https://doi.org/10.1037/1528-3542.7.1.147

Ortner, C. N. M., Kilner, S. J., & Zelazo, P. D. (2007). Mindfulness meditation and reduced emotional interference on a cognitive task. Motivation and Emotion, 31(4), 271–283. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-007-9076-7

Padmala, S., Sambuco, N., Codispoti, M., & Pessoa, L. (2018). Attentional capture by simultaneous pleasant and unpleasant emotional distractors. Emotion, 18(8), 1189–1194. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000401

Pandey, S., & Gupta, R. (2022a). Irrelevant angry faces impair response inhibition, and the go and stop processes share attentional resources. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-19116-5

Pandey, S., & Gupta, R. (2022b). Irrelevant positive emotional information facilitates response inhibition only under a high perceptual load. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-17736-5

Pavot, W., & Diener, E. (2008). The Satisfaction With Life Scale and the emerging construct of life satisfaction. Journal of Positive Psychology, 3(2), 137–152. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760701756946

Peirce, J., Gray, J. R., Simpson, S., MacAskill, M., Höchenberger, R., Sogo, H., Kastman, E., & Lindeløv, J. K. (2019). PsychoPy2: Experiments in behavior made easy. Behavior Research Methods, 51(1), 195–203. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-018-01193-y

Pessoa, L., McKenna, M., Gutierrez, E., & Ungerleider, L. G. (2002). Neural processing of emotional faces requires attention. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 99(17), 11458–11463. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.172403899

Pool, E., Brosch, T., Delplanque, S., & Sander, D. (2016). Attentional bias for positive emotional stimuli: A meta-analytic investigation. Psychological Bulletin, 142(1), 79–106. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000026

Randall, J. G., Oswald, F. L., & Beier, M. E. (2014). Mind-wandering, cognition, and performance: A theory-driven meta-analysis of attention regulation. Psychological Bulletin, 140(6), 1411–1431. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037428

Sedlmeier, P., Eberth, J., Schwarz, M., Zimmermann, D., Haarig, F., Jaeger, S., & Kunze, S. (2012). The psychological effects of meditation: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 138(6), 1139–1171. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028168

Simons, D. J. (2000). Attentional capture and inattentional blindness. Trends in Cognitive ScienCes, 4(4), 147–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1364-6613(00)01455-8

Slagter, H. A., Lutz, A., Greischar, L. L., Francis, A. D., Nieuwenhuis, S., Davis, J. M., & Davidson, R. J. (2007). Mental training affects distribution of limited brain resources. PLoS Biology, 5(6), 1228–1235. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.0050138

Smith, K. S., Berridge, K. C., & Aldridge, J. W. (2011). Disentangling pleasure from incentive salience and learning signals in brain reward circuitry. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 108(27). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1101920108

Strauman, T. J. (2017). Self-Regulation and Psychopathology: Toward an Integrative Translational Research Paradigm. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 13, 497–523. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032816-045012

Tang, Y. Y., Ma, Y., Wang, J., Fan, Y., Feng, S., Lu, Q., Yu, Q., Sui, D., Rothbart, M. K., Fan, M., & Posner, M. I. (2007). Short-term meditation training improves attention and self-regulation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 104(43), 17152–17156. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0707678104

Tang, Y. Y., Tang, R., Posner, M. I., & Gross, J. J. (2022). Effortless training of attention and self-control: Mechanisms and applications. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 26(7), 567–577. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2022.04.006

Taylor, V. A., Grant, J., Daneault, V., Scavone, G., Breton, E., Roffe-Vidal, S., Courtemanche, J., Lavarenne, A. S., & Beauregard, M. (2011). Impact of mindfulness on the neural responses to emotional pictures in experienced and beginner meditators. NeuroImage, 57(4), 1524–1533. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.06.001

Thompson, E. R. (2007). Development and validation of an internationally reliable short-form of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS). Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 38(2), 227–242. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022106297301

Valentine, E. R., & Sweet, P. L. G. (1999). Meditation and attention: A comparison of the effects of concentrative and mindfulness meditation on sustained attention. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 2(1), 59–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674679908406332

Van Dam, N. T., van Vugt, M. K., Vago, D. R., Schmalzl, L., Saron, C. D., Olendzki, A., Meissner, T., Lazar, S. W., Kerr, C. E., Gorchov, J., Fox, K. C. R., Field, B. A., Britton, W. B., Brefczynski-Lewis, J. A., & Meyer, D. E. (2018). Mind the Hype: A Critical Evaluation and Prescriptive Agenda for Research on Mindfulness and Meditation. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 13(1), 36–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691617709589

Verdonk, C., Trousselard, M., Canini, F., Vialatte, F., & Ramdani, C. (2020). Toward a Refined Mindfulness Model Related to Consciousness and Based on Event-Related Potentials. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 15(4), 1095–1112. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691620906444

Wadlinger, H. A., & Isaacowitz, D. M. (2011). Fixing our focus: Training attention to regulate emotion. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 15(1), 75–102. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868310365565

Wang, Y., Xiao, L., Gong, W., Chen, Y., Lin, X., Sun, Y., Wang, N., Wang, J., & Luo, F. (2021). Mindful non-reactivity is associated with improved accuracy in attentional blink testing: A randomized controlled trial. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01377-4

Zeidan, F., Johnson, S. K., Diamond, B. J., David, Z., & Goolkasian, P. (2010). Mindfulness meditation improves cognition: Evidence of brief mental training. Consciousness and Cognition, 19(2), 597–605. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2010.03.014

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the fellowship from the University Grant Commission (378/(NET-NOV2017)) to Ms. Surabhi Lodha and IRCC, IITB seed grant to Prof. Gupta.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, SL and RG; Methodology, SL and RG; Formal analysis, SL and RG; Investigation, SL and RG; Resources, SL and RG; Data collection, SL; Data analysis, SL and RG; Writing, SL and RG; Funding acquisition, RG.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Link to Download Data

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Lodha, S., Gupta, R. Are You Distracted by Pleasure? Practice Mindfulness Meditation. J Cogn Enhanc 7, 61–80 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41465-023-00257-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41465-023-00257-y