Abstract

Adolescents with autism spectrum disorders (ASDs) often have difficulty with social interactions. This study aimed to increase social interactions in adolescents with ASD. Teachers developed friendship goals based on social skills outlined in the teaching-family model. Teachers provided reinforcement to students for displaying positive behaviors linked to goals throughout the school day. The current study also examined student, parent, and teacher perceptions of adolescent social interactions using interviews and surveys. During their interviews, adolescents reported that they were often lonely. Parents indicated that their children needed to learn skills to improve peer interactions. Observers used a behavioral system to quantify the types of social interactions displayed by adolescents. After a baseline period, teachers developed an intervention focusing on friendship goals to encourage students to engage in social interactions. The intervention had a limited impact on improving social interactions. The findings for the current study indicated limited improvement in social interactions resulting from the teacher-directed intervention. Parents, adolescents, and teachers highlighted the need for adolescents with ASDs to find ways to utilize social skills to reduce loneliness and improve peer support. Future research investigating the impact of teaching interaction/friendship skills around the students’ interests (e.g., sports) may help them learn skills to interact more with peers. Additionally, assessing the impact of individualized planning to improve each adolescent’s skills may be more influential in changing social behavior than a system-wide intervention, such as the one implemented in this study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a broad diagnostic category associated with problems in the areas of social communication, emotional intelligence, social recognition, and social interactions (Laugeson et al. 2012). Social impairment is arguably the most limiting symptom of this diagnosis, and social interaction and communication with others are pivotal for academic success and improved communication skills for adolescents with ASD (Sansosti 2010). However, social interactions may occur less frequently for adolescents with ASD than their typically developing peers (Cappadocia et al. 2012). Due to these social deficits, adolescents with ASD can be isolated and bullied at school, which increases their risk for low self-esteem and internalizing problems (e.g., depression; Tse et al. 2007). Thus, improving social involvement may boost mental health. In addition, improving social skills also increases vocational development, which will improve the future of youth with ASD (Tse et al. 2007). Research to determine factors influencing the interactions of and tools for measuring the social involvement of adolescents with ASD will contribute to literature and the growing need for interventions to improve social skills for adolescents with ASDs.

Adolescents with ASD spend less time in social interactions compared to their peers (Humphrey and Symes 2010). Isolation and loneliness may take a toll, eventually leading to negative and turbulent experiences in day-to-day interactions (Hughes et al. 2013). Improving communication skills and abilities to engage in social exchanges with peers reduces social isolation for youth with ASD (Koegel et al. 2013; Stichter et al. 2007). Several factors may contribute to improved interactions. For example, Koegel et al. (2013) found that communication skills increased in adolescents with ASD when their interactions with other youth focused on activities they found interesting. Feldman and Matos (2013) reported that adult involvement in classroom interactions facilitated the involvement of youth with autism in social exchanges. Furthermore, providing instruction about making friendship bids, speaking to, and interacting with classmates may increase the frequency of social interactions with peers and improve social development and reduce the feelings of isolation for adolescents with ASD (Tse et al. 2007). Instruction on social skills and interpersonal communication should be pivotal educational experiences for adolescents with ASD, but planning in this area can be under-developed in classroom settings where busy teachers have little time to implement and assess the impact of interventions to improve social involvement.

Most adolescents with ASD report having at least one friend (Bauminger and Kasari 2000; Locke et al. 2010). They define their friends as a person to talk with or do things with and as someone they can trust, who is kind (Locke et al. 2010). Adolescents with ASD may understand they have fewer friends, poorer social skills, and that their friendships might not be as close as their peers’ friendships (Bauminger et al. 2008; Rao et al. 2007). Establishing friendships with peers may be difficult because adolescents with ASD lack abilities to build relationships with others (Samuels and Stansfield 2012). These deficits reduce opportunities to build friendships and engage in interactions. Continued research will increase knowledge and provide information to develop interventions to improve the social development of adolescents with ASD.

Researchers have reviewed studies examining interventions to improve social the skills of adolescents with ASD, identifying several effective intervention strategies (e.g., Mason et al. 2015; McDonald and Machalicek 2013). Reinforcement and token economies have been successful in improving social communication (Matson and Boisjoli 2009). Mason et al. (2015) found that the reinforcement of verbal responses increased the verbal responding of a 15-year-old and a 17-year-old male with ASD. These adolescents worked one-on-one with behavioral technicians from a university program. Koegel et al. (2014) used a reinforcement and token system to improve the conversation skills of a 14-year-old boy with ASD. Points that could lead to earning rewards, such as increased computer time, were awarded for appropriate conversation, question asking, and interacting with a graduate student, who served as a conversation partner. This intervention was successful in increasing the levels of conversation and question asking. Less information is available about whether reward systems are effective in the classroom, in the hands of teachers (Parsons et al. 2013). Additionally, research examining class-wide interventions to improve the social communication of adolescents with ASD will determine if these types of interventions are effective when there are several adolescents with ASD in the same classroom.

One goal of this study was to examine the parent and adolescent perceptions of social skills and friendships for adolescents with ASD. Parents completed surveys and adolescents completed interviews to examine their perceptions of the adolescents’ social skills and friendships. Another goal of this study was to evaluate the outcomes of a teacher-directed intervention, emphasizing “friendship behaviors” to improve adolescents’ social skills. Behavior observations and teacher interviews were used to assess the impact of a friendship intervention to improve socialization with peers. It was anticipated that social behaviors (i.e., interactions with others, asking questions, and expression of positive emotions) would increase after the implementation of the intervention.

Method

Participants

Twenty youth (17 boys and 3 girls) enrolled in a private high school for adolescents with ASD participated in this study. Average age was 16 years, 2 months (ages ranged from 14 to 19 years). All of the youth were diagnosed with a primary diagnosis of ASD (90 %, n = 18) or a significant cognitive delay (10 %; one boy and one girl). The youth with cognitive delays as a primary diagnosis also exhibited symptoms that were consistent with a secondary diagnosis of ASD. The majority of youth were Caucasian (n = 17) and three were African-American. The high school included three classrooms, and on a typical day, a class size averaged about six or seven youth with 18 to 20 youth attending school regularly.

There was one lead teacher and at least one assistant teacher per classroom. There were six teachers (four males and three females). Five teachers were Caucasian and one was African-American. All had received special training for working with adolescents with ASD, and teachers were certified intervention specialists. There was a certified education specialist and an educational assistant working in each classroom. The assistant principal, a Caucasian female with a master’s degree in special education, consulted with the teachers on a daily basis. Two college students and a licensed psychologist served as observers and interviewers. There was a male and female college student and the psychologist was a female. Observers/interviewers were Caucasian.

The setting for the current study was a private high school for youth with ASD. The students at the high school were experiencing significant conversational and social skill deficits, which precluded their enrollment in public schools and in inclusive classroom settings. Teachers in the school setting were using key principles and goal setting developed through the Teaching-Family Model (TFM). Grounded in behavioral principles, the TFM is an evidence-based intervention with over 30 years of research supporting its impact on increasing grades, improving behavioral functioning, and reducing restrictiveness in different treatment settings (e.g., James 2011; Kingsley 2006; Kirigin 2001; see http://teaching-family.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/tfabibliography.pdf for a bibliography). The high school was certified as a TFM program by the Teaching-Family Association (www.teaching-family.org; http://www.teaching-family.org/aboutthemodel.pdf; http://teaching-family.org/teaching-family-research-development/). Students earned points for the attainment of their behavioral and academic goals, which they could exchange for prizes or “computer time” at the end of the week.

In addition to an individualized academic program (morning program), the school offered life skills and job readiness programming to help students prepare to be independent and productive adults (afternoon programming). Students also participated in other services including speech and occupational therapy, as well as specialized music and art programming.

Procedures

A university-based institutional review board approved this study. Parents provided consent and children provided assent to participate in this study.

At the outset of the project, parents completed a survey and students completed interviews to gather information on their perceptions of friendships and social skills. Parents returned surveys assessing their perceptions of their child’s friendships and social skills. Parents provided demographic information and then responded to seven questions: (1) How does your child make friends? (2) How many friends does your child have at school? (3) Does your child seem to enjoy social activities? (4) Please write down reasons for your answer about whether your child enjoys social activities. (5) Does your child ever appear lonely? (6) If they answered yes to question 5, they provided information about why their child appeared lonely and (7) What types of friendship skills are difficult for your child to engage in and why? Adolescents participated in semi-structured interviews that lasted approximately 5 to 10 min. Interview questions included: (1) “How do you make friends at school?” (2) “What do you talk about with your friends at school?” and (3) “Do you feel ‘O.K.’ telling your friends about personal or private things or secrets?”

An A-B single-case research design was used to examine the effects of the intervention on students’ behavior. There was a four-week baseline period where behavior observations were completed, followed by 7 weeks of intervention. During baseline, class instruction and implementation of the TFM program continued as usual. As part of the TFM program, teachers developed two to three behavioral goals for each student (i.e., following instructions, accepting “no” for an answer, showing respect). Each student’s goals also had specific behavioral steps to break down the behaviors for successful goal attainment. Teachers provided corrective feedback and reinforcement linked to each student’s goals throughout the day and reviewed progress toward goals with students at the end of the school day. Students received points when they exhibited behaviors consistent with their goals. They also received behavior-specific praise if they successfully performed one of the behavioral steps for their goals or actually successfully performed one of their goals. Teachers recorded point totals at the end of each school day in a log and students accumulated points throughout the week. Students could “spend” their points at a point store at the end of the week. Students could purchase either items, such as food or games, or rewards (e.g., increased computer time) at the point store.

Following baseline, teachers continued implementing the TFM program but added the intervention for this study, which consisted of three behavioral goals for all students: (1) beginning a conversation with another person, (2) joining in an interaction with others, and (3) offering to help a classmate. The component behaviors required (component parts of each goal) are presented in Table 1.

The behavioral goals focusing on friendship skills were added to existing goals for each student. Teachers awarded points for reaching friendship behavioral goals and other student goals throughout the day. Teachers discussed progress toward goals with students at the end of the day. Teachers implemented this intervention on a daily basis, throughout the school day, for 7 weeks. Observers recorded behavior observations throughout this intervention period.

After the intervention had been completed, teachers and the assistant principal completed interviews to discuss their perceptions about the implementation of the intervention and their views of student behavior before and during the intervention period. This data provided information about social validity and provided information about future ideas for improving the intervention. Teachers and the assistant principal also suggested ideas for improving adolescents’ social skills in the future.

Measurement: Behavior Observations

Students’ social behaviors were observed by three of the authors in the classroom using a structured direct observation code. Behavioral categories were modified from those developed by Gottman (1983) to assess social behaviors. Categories included the following: (1) positive emotional expression (toward another person), (2) negative emotional expression, (3) asking questions, (4) interaction with a peer, and (5) interaction with a teacher. A positive emotional expression was defined as positive feelings directed toward another person in a positive manner or with a positive tone (i.e., making a positive verbal statement, smiling, laughing). A negative emotional expression was defined as negative feelings, expressions, or emotional tone expressed toward a peer (frowning, yelling, or making a negative verbal statement). Asking a question involved asking another person to answer a question. Interaction with a peer or teacher consisted of talking with a teacher or peer. In order to deter reliability decay, observers reviewed the observation categories on a weekly basis (Bakeman and Gottman 1986).

Observers recorded behaviors at the end of a 2-min scanning period. One observer verbally signaled the start and end of a scan sample of the classroom, when there were two observers present in the classroom. If there were two observers present to determine inter-rater reliability, they stood at the sides of the classroom, at a distance, so they could not see what the other observer was recording. Observers scanned the room from the front to the back of the room and then recorded which behavioral categories occurred by placing a check mark in a box on a grid with categories for each of the five behaviors. Observers also recorded field notes below the grid as needed. Scan sampling has been used in previous research focusing on social interactions (e.g., Buhs and Ladd 2001).

Data Analyses

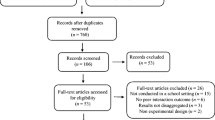

Researchers entered the data from behavior observations into a data analysis program (SPSS Version 20). Data from behavior observations were analyzed using percentages and chi-square analyses. Kappa coefficients were utilized to determine interobserver agreement for behavior observations. Descriptive analyses (frequency counts) were used to analyze descriptive data from interviews and surveys. In addition, content coding was used to determine key themes in qualitative data from interviews and surveys. Three of the researchers reviewed transcripts of the interview data (provided by teachers and students) and information recorded by parents on surveys in six meetings to determine key themes in the data (Strauss and Corbin 1990). Disagreements were resolved by consensus.

Results

Nine parents (eight females, one male) completed surveys; all were Caucasian. Four were in their “40s” and five were in their “50s.” Eight of the parents reported all of their adolescent’s friends were “at school.” One parent reported her child did not have any friends at school. One parent said her son had eight friends at school, but the others typically reported one, two, or three friends. Two parents reported their child had no skills for making friends, and one parent did not provide a response for this question. Seven parents reported their child appeared lonely. Four parents (44 %) reported they arranged meetings with friends for their adolescent. When asked whether their child enjoyed social activities, 33 % (n = 3) of the parents indicated “no,” 33 % indicated “yes,” and 33 % reported “sometimes.” Parents who reported their child did not enjoy social activities were likely to write that their child needed a parent to go with them to support their involvement with peers at social events. Parents reported that encouraging social skills around adolescents’ favorite activities had the potential to engage them in interactions. Parents wrote that adolescents needed to work on improving empathy skills, turn-taking in conversations, “fitting in,” and having patience with others (e.g., “he needs things done his own way in his own time”).

Thirteen of the twenty students at the school completed interviews to assess their perceptions of their friendships. There were eleven boys and two girls; three were African-American and ten were Caucasian. Seven of the youth (1 girl and 6 boys) were unable to explain how they made friends. Five of the youth (1 girl and 4 boys) reported they made friends by “talking” or “introducing myself.” One boy said he would make friends by “joining a conversation that is going on.” The students also provided information about what they talked about with friends. Specifically, two students, one boy and one girl, reported, “You speak to your friends about “anything.” Another boy said, “They talk about things that are already occurring in a conversation.” Two boys and one girl mentioned they speak about games, movies, or cartoons with friends. Two boys said, “I talk about my weekend.” One boy said he discussed “history” with his friends. Another boy reported he discussed sports with friends. Finally, another boy stated he spoke about “current events” with friends. Nine of the youth reported they would discuss personal or private things with a friend.

Two observers were present for 34 % of the observations. Kappa coefficients are presented in Table 2. Interobserver agreement for different behavioral categories was good.

Two hundred and three behavioral observations were recorded by the three observers. The frequencies for each type of behavior, across the 203 observations, were as follows: positive emotional expression 6.9 % (n = 14), negative emotional expression 7.4 % (n = 15), asking questions 43.3 % (n = 88), interaction with a peer 68.2 % (n = 137), and interaction with a teacher 60.7 % (n = 122).

Chi-square analyses were used to assess the behaviors observed before the implementation of the intervention, and then during the intervention period. Table 3 presents the frequencies of behavioral observations by category before and during the intervention.

There were significant differences for positive emotional expression, X 2 = 4.596, p = .024, and for asking questions, X 2 = 4.389, p = .026. Expression of positive emotion increased and questions decreased during the intervention. Chi-squares for change in negative emotional expression, interactions with peers, and interactions with teachers did not reveal significant differences. It is noteworthy that interactions with peers increased and interactions with teachers decreased after the implementation of the intervention, although differences were not statistically significant.

All of the teachers, except one, reported they believed using the three friendship goals was helpful in reinforcing skills that adolescents needed to be able to interact more with others in their classrooms. For example, one female teacher reported, “While the friendship goals were in effect I felt that the adolescents were, ‘respecting’ children’s (other peers) problems more.” She believed teaching the adolescents to respect each other was an important social goal. However, one teacher stated he was not sure all of the students recalled the friendship goals. Thus, he did not have complete confidence in the goals as being helpful to all of the students.

Teachers also discussed future goals for improving social skills. All of the teachers believed incorporating more field trips into their routine and ensuring the students were engaging in interactions during recreational activities would improve socialization among students.

The assistant principal felt that the intervention improved teachers’ focus on the development of social skills. She mentioned that the point store, as a reward system, might be more important to some of the students and less important to others. Specifically, she mentioned, “Some youth are motivated by the point store, while others are not. Some have difficulty waiting until the end of the week to earn a reward at the point store, which reduces value of the system.” She wanted to discuss the idea of tying the point system to privileges during flexible time (a time when adolescents could select what they wanted to do) so that students could earn time to participate in valued activities (e.g., computer time). Moreover, she felt that iPads and computers could detract from social opportunities. She stated that, “There are at least two computers at the back or corners of the rooms and this causes distraction.” She planned to work with staff to move classroom computers to an unoccupied classroom and meet with teachers to develop ideas for earning computer time for accomplishing personal goals.

Discussion

Consistent with existing literature, study results indicated that adolescents with ASD valued friendships, although parent report indicated that adolescents lacked skills and would benefit from interventions to improve social skills (Bauminger and Kasari 2000; Locke et al. 2010). Most parents reported that their child was lonely, which was consistent with the findings of previous studies (Hughes et al. 2013; Locke et al. 2010). Given that parents were providing a great deal of support for interactions outside of the school setting, it may have been advantageous to involve parents in the development of interventions. Social interactions with peers slightly increased and expression of positive emotions improved after teachers implemented the intervention. This may have been a precursor to significant amounts of involvement with peers, had the intervention period been longer. Interactions with adults reduced during the intervention period, perhaps because teachers were allowing adolescents more opportunities for interactions with their peers. Students were asking fewer questions during the intervention period, which may have been related to the lower frequency of interactions with teachers. However, further research is needed to confirm this idea.

However, over 50 % of the students’ interactions were with teachers, irrespective of the application of an intervention. Teachers’ encouragement of interactions with peers and awareness of reducing “one-on-one” interactions between themselves and youth may promote peer-to-peer interactions (Carter et al. 2013; Feldman and Matos 2013). Teachers can play a role in facilitating social interactions through incidental teaching opportunities where they can include other students in ongoing interactions. Teachers did report important areas for intervention, including improving empathy for others, reducing negative outbursts, respecting personal space of others, and improving students’ abilities to express their emotions with others. Developing behavioral goals in each of the aforementioned areas, and rewarding adolescents for reducing negative outbursts, respecting others’ personal space, and improving their skills for positive emotional expression during conversations with others may improve adolescents’ social skills in the future.

Students discussed a limited range of topics with friends, and the topics of conversation usually were limited to their own narrow range of interests. Developing situations in which adolescents can “practice” friendship goals may improve opportunities for adolescents with ASD to develop their social skills. Practice situations may be most effective when conversations revolve around an area of interest for students with ASD.

Limitations

Several factors could have limited the generalizability of study findings. For instance, some parents and youth did not provide complete interview and survey data, which may have limited the utility of our findings. In addition, observers did not record the sequence of events during behavioral interactions, which could have afforded data about the content and information reviewed in successful interactions. Observers did not record data about the number of youth involved in each interaction, so optimal group size for facilitating interactions could not be determined. It also may be the case that observers missed interactions occurring in different parts of the classroom as they were completing scan samples. However, the classrooms were small and the number of students in each class was small, making this unlikely. Some of the students may not have been sufficiently motivated to perform social behaviors, because there was a lag in receiving rewards, because they went to the point store at the end of the week. Moreover, other students may not have been motivated, because the rewards at the point store were not valuable to them. It also was not possible to determine the impact of TFM—whether components of this model influenced the adolescents’ social behaviors during the intervention period. However, findings still point to value added by when teachers added general social goals as a school-wide intervention. Findings are applicable to a special setting, a school for children with ASD, and future research is needed to determine the impact of goal setting in integrated classroom settings.

The results of this study provide new information about a teacher-directed social skills intervention that was integrated in a token system. Parent and teacher report supported the need for increased social skills training and provided ideas for interventions. Teacher report revealed that a “one size fits all” intervention may not be effective for many students. Other researchers have suggested that individualized planning using functional analyses of behavior is critical for advancing the skills of adolescents with ASD (Sansosti 2010). Teachers may benefit from consultation with school psychologists to develop individualized plans to improve peer interactions for adolescents with ASD. School psychologists can also provide advice on how to use functional analyses of behavior, develop goals, and assess the impact of interventions. In future studies, more immediate tangibles might be rewarding for adolescents. Improving social interactions should remain a high priority for interventions for youth with ASD (Laugeson et al. 2012). Individualized interventions that are part of the student’s educational planning may be needed to ensure social skills are developed and then generalized to interactions with peers (Cappadocia et al. 2012). After designing interventions, teachers and other school professionals can use existing token systems to reward social interactions. Observation of interactions can provide objective data about whether changes in social involvement occur.

References

Bakeman, R., & Gottman, J. M. (1986). Observing interaction: an introduction to sequential analysis. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Bauminger, N., & Kasari, C. (2000). Loneliness and friendship in high-functioning children with autism. Child Development, 71, 447–456.

Bauminger, N., Solomon, M., Aviezer, A., Heung, K., Gazit, L., Brown, J., & Rogers, S. J. (2008). Children with autism and their friends: a multidimensional study of friendship in high-functioning autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 36, 135–150.

Buhs, E. S., & Ladd, G. W. (2001). Peer rejection as an antecedent of young children’s school adjustment: an examination of mediating processes. Developmental Psychology, 37, 550–560.

Cappadocia, M., Weiss, J., & Pepler, D. (2012). Bullying experiences among children and youth with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42, 266–277.

Carter, E. W., Common, E. A., Srekovic, M. A., Huber, H. B., Bottema-Beutel, K., Gustafson, J. R., et al. (2013). Promoting social competence and peer relationships for adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Remedial and Special Education, 35, 91–101. doi:10.1177/0741932513514618.

Feldman, E. K., & Matos, R. (2013). Training paraprofessionals to facilitate interactions between children with autism and their typically developing peers. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 15, 169–179.

Gottman, J. M. (1983). How children become friends. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 48(3, Serial No. 201).

Hughes, C., Bernstein, R. T., Kaplan, L. M., Reilly, C. M., Brigham, N. L., Cosgriff, J. C., & Boykin, M. P. (2013). Increasing conversational interactions between verbal high school students with autism and their peers without disabilities. Focus on Autism And Other Developmental Disabilities, 28, 241–254.

Humphrey, N., & Symes, W. (2010). Perceptions of social support and experience of bullying among pupils with autistic spectrum disorders in mainstream secondary schools. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 25, 77–91. doi:10.1080/08856250903450855.

James, S. (2011). What works in group care?—a structured review of treatment models for group homes and residential care. Child and Youth Services Review, 33, 308–321.

Kingsley, D. (2006). The teaching-family model and post-treatment recidivism: a critical review of the conventional wisdom. International Journal of Behavioral and Consultation Therapy, 2, 481–497.

Kirigin, K. A. (2001). The teaching-family model: a replicable system of care. Residential Treatment for Children and Youth, 18, 99–110.

Koegel, R., Kim, S., Koegel, L., & Schwartzman, B. (2013). Improving socialization for high school students with ASD by using their preferred interests. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43, 2121–2134. doi:10.1007/s10803-013-1765-3.

Koegel, L. K., Park, M. N., & Koegel, R. L. (2014). Using self-management to improve the reciprocal social conversation of children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(5), 1055–1063. doi:10.1007/s10803-013-1956-y.

Laugeson, E. A., Frankel, F., Gantman, A., Dillon, A. R., & Mogil, C. (2012). Evidence-based social skills training for adolescents with autism spectrum disorders: the UCLA PEERS program. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42, 1025–1036.

Locke, J., Ishijima, E. H., Kasari, C., & London, N. (2010). Loneliness, friendship quality and the social networks of adolescents with high-functioning autism in an inclusive school setting. Journal of Research in Special Education Needs, 10, 74–81. doi:10.1111/j.1471-3802.2010.01148.x.

Mason, L., Davis, D., & Andrews, A. (2015). Brief report: token reinforcement of verbal responses controlled by temporarily removed verbal stimuli. Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 31, 145–153. doi:10.1007/s40616-015-0032-4.

Matson, J. L., & Boisjoli, J. A. (2009). The token economy for children with intellectual disability and/or autism: a review. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 30, 240–248.

McDonald, T. A., & Machalicek, W. (2013). Systematic review of intervention research with adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 7, 1439–1460.

Parsons, S., Charman, T., Faulkner, R., Ragan, J., Wallace, S., & Wittemeyer, K. (2013). Commentary—bridging the research and practice gap in autism: the importance of creating research partnerships with schools. Autism, 17, 268–280.

Rao, P., Beidel, D., & Murray, M. (2007). Social skills interventions for children with Asperger’s syndrome or high-functioning autism: a review and recommendations. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38, 353–361.

Samuels, R., & Stansfield, J. (2012). The effectiveness of social stories to develop social interactions with adults with characteristics of autism spectrum disorder. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 40, 272–285.

Sansosti, F. J. (2010). Teaching social skills to children with autism spectrum disorders using tiers of support: a guide for school-based professionals. Psychology in the Schools, 47, 257–281.

Stichter, J. P., Randolph, J., Gage, N., & Schmidt, C. (2007). A review of recommended social competency programs for students with autism spectrum disorders. Exceptionality, 15, 219–232.

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of qualitative research: grounded theory procedures and techniques. Newbury Park: Sage.

Tse, J., Strulovitch, J., Tagalakis, V., Meng, L., & Fombonne, E. (2007). Social skills training for adolescents with Asperger syndrome and high-functioning autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37, 1960–1968. doi:10.1007/s10803-006-0343-3.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nabors, L., Hawkins, R., Yockey, A.R. et al. Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Friendships and Social Interactions. Adv Neurodev Disord 1, 14–20 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41252-016-0001-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41252-016-0001-5