Abstract

Despite increasing numbers of adolescents experiencing poor mental wellbeing, adolescents are often reluctant to seek help for mental health problems. In response, there is increasing interest in the development of evidence-based interventions to increase help-seeking behavior. However, the evidence base may lack validity if help-seeking measures used in adolescent research contain age-inappropriate language or content such as seeking help from a spouse; no previous review has assessed this. A review of adolescent mental health help-seeking research was conducted to identify help-seeking measures used, assess their psychometric properties and linguistic appropriateness in adolescent populations, and organize measures by facet of help-seeking for ease of future use. We found 14 help-seeking measures used in adolescent research, but only 17/72 (24%) studies found used one of the identified measures. Help-seeking measures identified were categorized into one of four help-seeking facets: attitudes toward help-seeking, intentions to seek help, treatment fears regarding help-seeking, and barriers to help-seeking. The content and language of measures were deemed appropriate for all but one help-seeking measure. Recommendations for future research include greater utilization of identified measures, particularly in researching help-seeking behavior in different cultures, subcultures and between stages of adolescence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Increasing numbers of young people experience poor mental health (Meltzer et al. 2003), with 20–25% of mental health disorders being diagnosed in adolescence and emerging adulthood (Gore et al. 2011). It is recommended for those suffering from poor mental health to communicate their difficulties to others as a method of seeking assistance and further treatment options; this is known as mental health help-seeking (Rickwood et al. 2012). These difficulties may be communicated to informal sources of help such as family members, or formal sources such as mental health practitioners. While the prevalence of poor mental health is increasing in young people, mental health help-seeking remains low: only one-third of adolescents meeting diagnostic criteria for a mental health diagnosis seek professional help (Green et al. 2005; World Federation for Mental Health 2009). Adolescents suffering from serious and debilitating mental health difficulties may still avoid seeking help or considerably delay getting appropriate help (Biddle et al. 2006; Goodman et al. 2002). Failing to seek help or delaying the help-seeking process can lead to adverse health outcomes such as substance abuse, engaging in risky sexual behavior, lower quality of adult life and premature death (Anderson and Lowen 2010; Brindis et al. 2002, 2007; Laski 2015).

Current research suggests that when adolescents engage in help-seeking, they are more comfortable doing so from informal sources such as parents (Rickwood et al. 2005). While parents can be a valuable resource for initiating the referral process for formal help-seeking (Langeveld et al. 2010), parental referrals occur disproportionately in families with a higher socioeconomic status (Benjet et al. 2016). This finding places economically vulnerable adolescents at risk as they are otherwise unwilling to speak with formal sources of help (Leavey et al. 2011). Investigations into why adolescents may be unwilling to engage in formal help-seeking have uncovered barriers such as fears of unfriendly clinicians, the fear of receiving a “stigmatizing” mental health diagnosis, and the fear of being treated “like a child” by clinicians (Rickwood et al. 2007; Zachrisson et al. 2006; Corry and Leavey 2017). Barriers to informal help-seeking have also been identified such as fearing negative judgment from friends and family (Gulliver et al. 2010). The fear of negative judgment from others is heightened in certain cultures (Chen et al. 2014), with parents of Moroccan and Turkish adolescents fearing judgment from the community if their child sought help (Flink et al. 2013). In order to improve help-seeking behavior in adolescents, it is imperative to understand why such help-seeking barriers exist and how they can be broken down.

There is a growing policy interest in developing early intervention programs to break down barriers to adolescent help-seeking (Biddle et al. 2006; Rickwood et al. 2007; Rothì and Leavey 2006). In order to develop effective interventions to encourage help-seeking, the research base must be examined to achieve greater understanding of these help-seeking barriers and how they may be overcome. However, a review by the World Health Organization posits that the adolescent help-seeking research base may be flawed in two key areas that impact the development of interventions (Barker 2007). The first issue put forth by the review refers to a lack of knowledge of how reliable and valid help-seeking measures are when used in adolescent populations. Previous reviews of help-seeking measures on adult populations have found that reporting psychometric properties in help-seeking research is a relatively uncommon practice: only 38% of help-seeking studies identified reported psychometric properties (Wei et al. 2015). This limits our knowledge of whether help-seeking measures are reliable and valid outside of populations beyond the initial assessment population. The second issue identified is the lack of a clear definition of what help-seeking as a research area encompasses. While help-seeking involves a number of topics such as attitudes towards clinicians and fearing negative judgment from others (Rickwood et al. 2007; Zachrisson et al. 2006; Corry and Leavey 2017), no previous review has attempted to identify and synthesize the multiple facets of help-seeking behavior and the measures available to assess these factors. The review argues that greater clarity is needed regarding the multiple facets of help-seeking behavior and the measures available to assess these facets.

The lack of clarity and knowledge on validity of help-seeking measures hinders adolescent help-seeking interventions for two reasons. Firstly, no review has explored whether measures used in the current adolescent help-seeking research base are reliable, valid and age-appropriate. For example, measures which include questions pertaining to the workplace or the raising of children are often not relevant to adolescents. If interventions are developed using data gathered from measures that are not valid or age-appropriate, this limits the validity of interventions as measures are not truly capturing the beliefs and behaviors of adolescents. Secondly, the lack of clarity on help-seeking measures and which help-seeking facet they measure may act as a deterrent for future help-seeking research. It is paramount that researchers are aware of potential measures to use in the field, which facets of help-seeking they assess and whether they are valid and age-appropriate for adolescent use. This clarity can facilitate future research and aid the development of interventions by exploring help-seeking barriers in various populations and potentially identifying new help-seeking barriers.

Current Study

While the number of adolescents experiencing poor mental health is increasing, mental health help-seeking remains low. Policy interest in evidence-based help-seeking interventions is increasing, but the research base contains limitations. No previous review has explored whether help-seeking measures used in adolescent research are reliable, valid and age-appropriate for this population, potentially harming the validity of interventions. To address this limitation, a review of adolescent mental health help-seeking research was conducted with three aims. The first aim was to identify and organize all help-seeking measures used in adolescent research by their corresponding facet of help-seeking. The second aim was to record the psychometric properties of these measures to gauge their reliability and validity for adolescent populations. The third aim was to review the content and linguistic appropriateness of identified measures to ensure that questions are applicable and understandable to adolescents.

Methods

Search Strategy

The search terms “help-seeking”, “adolescence”, “adolescent”, “youth”, “young people” and “mental health” were used to locate journal articles in the following databases: Science Direct, Web of Knowledge, JSTOR, Wiley Online Library, SAGE Journals Online, PubMed, Google Scholar and Ingenta. Articles were also obtained via reference-chaining of articles deemed to be relevant for the review. This search was undertaken by three reviewers between January 2012 and September 2016.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Studies were retained if they assessed attitudes, beliefs, intentions or engagements toward mental health help-seeking in adolescents; no restriction was placed on year of publication. Journal articles were excluded if they were not written in English, if they assessed physical health help-seeking only, or if the study’s sample did not include an adolescent population. For the purpose of this review, this was defined as a lower limit of 11 years old and an upper limit of 18 years old.

Data Extraction

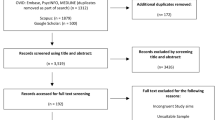

Where articles met the inclusion criteria, information was recorded as to how help-seeking was measured in the study. The psychometric properties of measures were also recorded where applicable. If a study used a pre-existing measure, the origin article of the measure was sourced to obtain information on its content and original psychometric properties. Measures were then read by the reviewers to ensure that there was no age-inappropriate content for adolescents such as discussing spouses or work colleagues. The extraction progress can be summarized in Fig. 1.

Results

Search Results

Following the review’s inclusion criteria, 72 studies were retained which assessed factors related to help-seeking in an adolescent population; this process has been outlined in Fig. 2. Out of 72 studies, 14 measures were identified which measured facets of help-seeking. These measures were found to assess four distinct facets: attitudes toward help-seeking, intentions to seek help, treatment fears regarding help-seeking, and barriers to help-seeking. However, use of these scales was found to be low as only 17/72 (24%) studies used an identified scale. Of the 17 studies identified, 12/17 (71%) reported at least one psychometric property.

Each identified scale, its original psychometric properties and its psychometric properties when used in adolescent research can be viewed in Table 1. We discuss these scales in respect to their corresponding help-seeking facet.

Attitudes Toward Help-Seeking

Three scales were used in help-seeking research to assess adolescents’ attitudes toward seeking help. The first scale was the Attitudes Toward Seeking Professional Psychiatric Help Scale (ATSPPHS; Fischer and Turner 1970), consisting of 29 items which evaluate attitudes toward seeking help from professional sources. It has four sub-scales: recognition of personal need for professional help, tolerance of stigma associated with psychological help, interpersonal openness, and confidence in mental health professionals. The ATSPPHS was also adapted into a ten-item short form version of the scale (ATSPPHS-SF; Fischer and Farina 1995).

Similarly, the Inventory of Attitudes toward Seeking Mental Health Services scale (IASMHS; Mackenzie et al. 2004) assesses inclination to seek help from a trained mental health professional and consists of 24 items within three sub-scales: psychological openness, help-seeking propensity, and indifference to stigma. While the ATSPPHS and ATSPPHS-SF do not include questions that would be inappropriate or inapplicable to adolescents, the IASMHS includes questions pertaining to co-workers and spouses. The adolescent study which used the IASMHS did not detail how these questions were managed (Perry et al. 2014).

Intentions to Seek Help

Five scales measured help-seeking intentions. The General Help Seeking Questionnaire (GHSQ; Wilson et al. 2005) examines the intentions of the respondent to seek help from several sources. These sources range from informal sources (such as family and teaching staff) to professional sources such as the family doctor. This was the most commonly used measure identified in the review.

Two scales assessing the use of professional sources of help are the Intentions to Seek Professional Help Questionnaire (ISPHQ; O’Connor et al. 2014) and the Intentions to Seek Counseling Inventory (ISCI; Cash et al. 1978). The ISPHQ consists of five questions on willingness to use professional help and how proactive they would be in seeking treatment. The ISCI presents participants with 17 known influencers of poor mental health (such as anxiety and loneliness) and asks how likely they would be to seek counseling for each of these influencers. For assessing utilization of social support, the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS; Zimet et al. 1988) is a 12-item questionnaire which measures the quality of support and ability to seek help from significant others, friends and family.

The Children’s Coping Strategies Checklist (CCSC; Ayers et al. 1996) contains 45 items which correspond to the following sub-scales: (a) problem-focused strategies; (b) direct emotion-focused strategies; (c) distraction strategies; (d) avoidant strategies; and (e) support-seeking strategies. The CCSC uniquely considers help-seeking along with several behaviors and strategies that young people may use to negate negative feelings. Although the CCSC was primarily developed for use with children, it was found to be reliable for use in an adolescent sample (Rodriguez et al. 2014). We found that all scales used to measure help-seeking intentions used language that was appropriate and relevant to adolescents.

Treatment Fears Regarding Help-Seeking

The main scale used for the analysis of treatment fear is the Thoughts About Psychotherapy Survey (TAPS; Deane and Chamberlain 1994). This scale has been adapted from the Thoughts About Counseling Scale (Pipes et al. 1985), adding more questions and additional sub-scales. The TAPS contains four sub-scales which assess the following factors: (a) therapist responsiveness (perceived competence of counselors or therapists); (b) image concerns (how the respondent feels about themselves); (c) coercion concerns (perceived lack of autonomy by accessing therapy); and (d) stigma concerns (how they believe others view their diagnosis). This scale was considered to be appropriate and applicable to adolescents.

Barriers to Help-Seeking

Five scales were identified for assessing barriers to help-seeking in adolescents. The Barriers to Adolescents Seeking Help scale (BASH; Kuhl et al. 1997) includes 37 items assessing 13 help-seeking barriers such as self-sufficiency and knowledge of resources. This scale was shortened to form the BASH-B (Vogel et al. 2006), an 11-item version which specifically retains items relating to barriers to professional help-seeking.

The Barriers to Help-Seeking Scale (BHSS) (Mansfield et al. 2005) consists of 31 items corresponding to five sub-scales: (a) need of control and self-reliance; (b) minimizing problems and resignation; (c) concrete barriers and distrust of caregivers; (d) concerns about privacy; and (e) concerns about emotional control. The Self-Stigma of Seeking Help scale (SSOSH; Vogel et al. 2006) assesses the degree to which participants may avoid help-seeking to preserve autonomy and self-worth. The scale contains ten items related to the factor of self-stigma, a concept which refers to the internalization of stigmatizing attitudes about mental illness such as negative social attitudes and stereotypical behaviors about people with mental illness (Dinos et al. 2004; Major and O’Brien 2005). Finally, the Barriers to Access to Care Evaluation scale (BACE) (Clement et al. 2012) is a 30-item questionnaire which assesses both stigma and non-stigma related barriers to seeking mental health services. The stigma subscale can be divided into self-stigma (judging oneself) and external stigma (fearing judgment from others), while non-stigma barrier questions enquire about knowledge of resources, previous negative experience with healthcare workers and fears of negative repercussions such as involuntary hospitalization. We found that all scales used to measure barriers to help-seeking used language that was appropriate and relevant to adolescents.

Discussion

The adolescent population is experiencing an increase in poor mental wellbeing (Gore et al. 2011), but adolescents’ willingness to engage in mental health help-seeking remains low (Green et al. 2005; World Federation for Mental Health 2009). Encouraging help-seeking behavior in adolescence is important for reducing future risk behaviors and fostering a higher quality of adult life (Anderson and Lowen 2010; Brindis et al. 2007). Interventions to encourage help-seeking behavior should aim to break down barriers to help-seeking identified in research, but this research base contains limitations. No previous review has investigated whether help-seeking measures are valid and age-appropriate for adolescent use, potentially harming the validity of interventions. Help-seeking as a research topic may also be difficult to measure due to a lack of clear understanding of the multiple facets of help-seeking and how they can be assessed. To address these limitations, a review of adolescent help-seeking research was conducted.

This review identified help-seeking measures used in adolescent research, organized each measure into its respective help-seeking facet, noted the psychometric properties of each measure in adolescent use, and assessed the linguistic and content appropriateness of measures for adolescent use. The review uncovered 72 studies which used 14 pre-existing measures to assess four facets of adolescent help-seeking: attitudes toward help-seeking, intentions to seek help, treatment fears regarding help-seeking and barriers to help-seeking. However, an unexpected finding from the review revealed that use of these measures was relatively low. Of the 72 studies identified which measured adolescent help-seeking, only 17 (24%) used one of the measures identified in the review; 12/17 (71%) reported at least one psychometric property when used in an adolescent sample. These findings indicate the existence of numerous help-seeking measures that are applicable and valid for adolescent use, yet are not often utilized.

Studies that did not use a pre-existing measure used self-developed single-use measures or used techniques such as vignettes. Single-use scales most commonly included a list of sources, both formal and informal, from which participants might seek help from. Help-seeking vignettes were used in a number of ways. Vignettes would typically describe someone suffering from a mental illness such as depression. Participants were then asked if they would seek help if they were experiencing similar symptoms (Sawyer et al. 2012) or if they would be happy to talk to this person about their illness (Wright et al. 2011). Studies using single-use scales did not disclose how these measures were developed, their psychometric properties, their factor structures or whether they were subject to prior testing via pilot studies. As adolescent help-seeking has been critiqued as a research field which lacks clarity in the multiple facets that it encompasses (Barker 2007), it is possible that the low utilization of pre-existing measures is a direct result of the lack of clarity in the field. The current review may serve as a useful tool for prospective adolescent help-seeking researchers by identifying and categorizing help-seeking measures that are suitable for adolescent use into their respective help-seeking facet.

Although the use of established help-seeking measures in adolescent research was relatively low, it was found that adolescent studies which did use pre-existing measures were nearly twice as likely to report at least one psychometric property than adult studies (Wei et al. 2015). While this is a positive finding from the review, it should be noted that 100% of psychometric properties reported in adolescent research were reliability statistics. This is an understandable limitation as researchers may lack time and space in publications to conduct and report on validity assessments. Instead, conducting validity tests such as construct and criterion validity on adolescents may be an avenue for future research to further ensure the appropriateness of measures in this population.

All but one of the measures reviewed were deemed appropriate for adolescent use. In the IASMHS (Mackenzie et al. 2004) scale, participants are asked how they would feel if their spouse and their work colleagues knew that they had sought help from mental health services. The adolescent study that used the IASMHS did not comment on how these questions were managed in the study. Two recommendations can be made from this finding. Firstly, in studies where measures are used which include content not entirely applicable to the target population, researchers should uphold transparency and state how these questions were managed in the study. Secondly, future studies may adapt items from the IASMHS to be adolescent-friendly (such as “partner” and “classmates” respectively) and assess whether the measure retains the same factor structure in the population.

This review allowed for the examination of the adolescent help-seeking research base and the identification of gaps in knowledge that should be addressed for future interventions. Two research gaps were identified in this review. The first research gap identified was a lack of research from poor help-seeking countries such as Japan and Nigeria (Wang et al. 2007). An examination of help-seeking beliefs in countries with the lowest rates of help-seeking would provide valuable insight into adolescent help-seeking barriers, but this was not possible to achieve in this review. We also did not uncover any studies which primarily investigated ethnic minority populations or refugee youths. While adult research of these populations suggest the presence of population-specific help-seeking barriers such as lack of trust (Lindsey et al. 2013; Leavey et al. 2004, 2007; Chakraborty et al. 2009), there is insufficient evidence to establish whether these cultural help-seeking barriers exist in adolescence. Future research should explore help-seeking beliefs in these cultures and sub-cultures to identify barriers to help-seeking that should be deconstructed. The second research gap identified was a lack of research exploring help-seeking differences between younger and older adolescents. This would be of interest for future help-seeking interventions due to differences in physical and emotional changes and coping strategies between these age groups. Younger adolescents may struggle with social, biological and hormonal changes (Currie et al. 2001) and fear being infantilized by mental health services (Corry and Leavey 2017), while older adolescents may be challenged with school examinations (Currie et al. 2001) and view help-seeking as a threat to their newly-established sense of autonomy (Richardson et al. 2014). It would be beneficial to explore which stage of adolescence is most receptive to the breaking down of help-seeking barriers in order to maximize the success of future interventions.

Conclusion

There is a growing policy interest in adolescent mental health help-seeking due to its role in alleviating poor mental wellbeing. However, the validity of evidence-based adolescent help-seeking interventions may be hindered by research conducted with age-inappropriate measures. A review of adolescent help-seeking research was conducted to identify all help-seeking measures used, assess their psychometric properties, assess their linguistic appropriateness for adolescent use and categorize identified measures for the convenience of future researchers. This review uncovered 14 help-seeking measures used in adolescent help-seeking research. These measures were categorized into one of four help-seeking facets: attitudes toward help-seeking, intentions to seek help, treatment fears regarding help-seeking, and barriers to help-seeking. 13/14 measures were deemed appropriate for adolescent use and 71% of adolescent help-seeking studies reported at least one psychometric property, but only 24% of adolescent help-seeking studies used one of the validated measured identified in the review. Adolescent help-seeking studies frequently use single-use scales and vignettes, and lack information on any prior testing or psychometric properties. Future adolescent help-seeking research could benefit from using measures identified in the review to explore under-researched areas such as cultural barriers to help-seeking and differences in help-seeking between younger and older adolescents.

References

Anderson, J. E., & Lowen, C. A. (2010). Connecting youth with health services: Systematic review. Canadian Family Physician, 56, 778–784.

Ayers, T. S., Sandler, I. N., West, S. G., & Roosa, M. W. (1996). A dispositional and situational assessment of children’s coping: testing alternative models of coping. Journal of Personality, 64(4), 923–958.

Barker, G. (2007). Adolescents, social support and help-seeking behaviour: An international literature review and programme consultation and recommendations for action. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/43778/1/9789241595711_eng.pdf. Accessed 10 Oct 2016.

Beals-Erickson, S. E., & Roberts, M. C. (2016). Youth development program participation and changes in help-seeking intentions. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25(5), 1634–1645.

Benjet, C., Borges, G., Méndez, E., Albor, Y., Casanova, L., Orozco, R., Curiel, T., Fleiz, C., & Medina-Mora, M. E. (2016). Eight-year incidence of psychiatric disorders and service use from adolescence to early adulthood: longitudinal follow-up of the Mexican Adolescent Mental Health Survey. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 25, 163–173.

Biddle, L., Donovan, J., Gunnell, D., & Sharp, D. (2006). Young adults’ perceptions of GPs as a help source for mental distress: A qualitative study. British Journal of General Practice, 56, 924–931.

Bradford, S., & Rickwood, D. (2014). Adolescent’s preferred modes of delivery for mental health services. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 19, 39–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/camh.12002.

Brindis, C., Hair, E., Cochran, S., Cleveland, K., Valderrama, L., & Park, M. (2007). Increasing access to program information: A strategy for improving adolescent health. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 11, 27–35.

Brindis, C., Park, M. J., Ozer, E. M., & Irwin, C. E. Jr. (2002). Adolescents’ access to health services and clinical preventive health care: crossing the great divide. Pediatric Annals, 31, 575–81.

Cakar, F. S., & Savi, S. (2014). An exploratory study of adolescent’s help-seeking sources. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 159, 610–614. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.12.434.

Cash, T. F., Kehr, J., & Salzbach, R. F. (1978). Help seeking attitudes and perceptions of counsellor behaviour. Journal of Counselling Psychology, 1(25), 264–269.

Chakraborty, A. T., McKenzie, K., Leavey, G., & King, M. (2009). Measuring perceived racism and psychosis in African-Caribbean patients in the United Kingdom: The modified perceived racism scale. Clinical Practice and Epidemiology in Mental Health, 5(1), 1.

Chen, H., Fang, X., Liu, C., Hu, W., Lan, J., & Deng, L. (2014). Associations among the number of mental health problems, stigma, and seeking help from psychological services: A path analysis model among Chinese adolescents. Children and Youth Services Review, 44, 356–362. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.07.003.

Clement, S., Brohan, E., Jeffery, D., Henderson, C., Hatch, S. L., & Thornicroft, G. (2012). Development and psychometric properties the Barriers to Access to Care Evaluation scale (BACE) related to people with mental ill health. BMC Psychiatry, 12(1), 36.

Coppens, E., Van Audenhove, C., Scheerder, G., Arensman, E., Coffey, C., Costa, S., Koburger, N., Gottlebe, K., Gusmão, R., O’Connor, R., Postuvan, V., Sarchiapone, M., Sisask, M., Székely, A., van der Feltz-Cornelis, C., & Hegerl, U. (2013). Public attitudes toward depression and help-seeking in four European countries baseline survey prior to the OSPI-Europe intervention. Journal of Affective Disorders, 150(2), 320–329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2013.04.013.

Corry, D. A., & Leavey, G. (2017). Adolescent trust and primary care: Help-seeking for emotional and psychological difficulties. Journal of Adolescence, 54, 1–8.

Currie, C., Samdal, O., Boyce, W., & Smith, R. (2001). Health behaviour in school-aged children: A WHO cross-national study (HBSC), research protocol for the 2001/2002 survey Child and Adolescent Health Research Unit (CAHRU), University of Edinburgh.

Deane, F. P., & Chamberlain, K. (1994). Treatment fearfulness and distress as predictors of professional psychological help-seeking. British Journal of Guidance and Counselling, 22(2), 207–217.

Dinos, S., Stevens, S., Serfaty, M., Weich, S., & King, M. (2004). Stigma: The feelings and experiences of 46 people with mental illness. British Journal of Psychiatry, 184, 176–181.

Elhai, J., Schweinle, W., & Anderson, S. (2008). Reliability and validity of the attitudes toward seeking professional psychiatric help scale—short form. Psychiatry Research, 159(3), 320–329.

Fischer, E. H., & Farina, A. (1995). Attitudes towards seeking professional psychological help: A shortened form and considerations for research. Journal of College Student Development, 36, 368–373.

Fischer, E. H., & Turner, J. L. (1970). Orientations to seeking professional help: Development and research utility of an attitude scale. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 35(1), 79–90. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0029636.

Fitzpatrick, C., Conlon, A., Cleary, D., Power, M., King, F., & Guerin, S. (2013). Enhancing the mental health promotion component of a health and personal development programme in Irish schools. Advances in School Mental Health Promotion, 6(2), 122–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/1754730X.2013.784617.

Flink, I. J. E., Beirens, T. M. J., Butte, D., & Raat, H. (2013). The role of maternal perceptions and ethnic background in the mental health help-seeking pathway of adolescent girls. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 15(2), 292–299.

Goodman, R., Ford, T., & Meltzer, H. (2002). Mental health problems of children in the community: 18 month follow up. British Medical Journal, 324, 1496–1497.

Gore, F. M., Bloem, P. J., Patton, G. C., Ferguson, J., Joseph, V., Coffey, C., Sawyer, S. M., & Mathers, C. D. (2011). Global burden of disease in young people aged 10–24 years: a systematic analysis. Lancet, 377, 2093–2102.

Green, H., McGinnity, Á, Meltzer, H., Ford, T., & Goodman, R. H. (2005). Mental health of children and young people in Britain. Palgrave: Hampshire.

Gulliver, A., Griffiths, K. M., & Christensen, H. (2010). Perceived barriers and facilitators to mental health help-seeking in young people: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry, 10(113), 1–9.

Jackson Williams, D. (2013). Help-seeking among jamaican adolescents: An examination of individual determinants of psychological help-seeking attitudes. Journal of Black Psychology, 40, 359–383. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095798413488940.

Kuhl, J., Jarkon-Horlick, L., & Morrissey, R. F. (1997). Measuring barriers to help-seeking behavior in adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 26(6), 637–650. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022367807715.

Langeveld, J. H., Israel, P., & Thomsen, P. H. (2010). Parental relations and referral of adolescents to Norwegian mental health clinics. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 64(5), 327–333.

Laski, L. (2015). Realising the health and wellbeing of adolescents. British Medical Journal, 351, h4119.

Leavey, G., Hollins, K., King, M., Barnes, J., Papadopoulos, C., & Grayson, K. (2004). Psychological disorder amongst refugee and migrant schoolchildren in London. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 39, 191–195. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-004-0724-x.

Leavey, G., Rothi, D., Paul, R. (2011). Trust, autonomy and relationships: the help-seeking preferences of young people in secondary level schools in London (UK). Journal of Adolescence, 34(2), 685–693.

Leshem, B., Haj-Yahia, M. M., & Guterman, N. B. (2015). The characteristics of help seeking among Palestinian adolescents following exposure to community violence. Children and Youth Services Review, 49, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.12.022.

Lindsey, M. A., Chambers, K., Pohle, C., Beall, P., & Lucksted, A. (2013). Understanding the behavioral determinants of mental health service use by urban, under-resourced black youth: adolescent and caregiver perspectives. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 22(1), 107–121. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-012-9668-z.

Mackenzie, C. S., Knox, V. J., Gekoski, W. L., & Macaulay, H. L. (2004). An adaptation and extension of the attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help scale. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 34, 2410–2433. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2004.tb01984.x.

Major, B., & O’Brien, L. T. (2005). The social psychology of stigma. Annual Review of Psychology, 56, 393–421.

Mansfield, A. K., Addis, M. E., & Courtenay, W. (2005). Measurement of men’s help seeking: Development and evaluation of the barriers to help seeking scale. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 6(2), 95–108. https://doi.org/10.1037/1524-9220.6.2.95.

Meltzer, H., Gatward, R., Goodman, R., & Ford, T. (2003). Mental health of children and adolescents in Great Britain. International Review of Psychiatry, 15, 185–187.

O’Connor, P. J., Martin, B., Weeks, C. S., & Ong, L. (2014). Factors that influence young people’s mental health help-seeking behaviour: A study based on the Health Belief Model. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 70, 2577–2587. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.12423.

Perry, Y., Petrie, K., Buckley, H., Cavanagh, L., Clarke, D., Winslade, M., Hadzi-Pavlovic, D., Manicavasagar, V., & Christensen, H. (2014). Effects of a classroom-based educational resource on adolescent mental health literacy: A cluster randomised controlled trial. Journal of Adolescence, 37(7), 1143–1151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2014.08.001.

Pipes, R. B., Schwarz, R., & Crouch, P. (1985). Measuring client fears. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 53(6), 933–934.

Richardson, L. P., Ludman, E., McCauley, E., Lindenbaum, J., Larison, C., Zhou, C., Clarke, G., Brent, D., & Katon, W. (2014). Collaborative care for adolescents with depression in primary care: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of the American Medical Association, 312(8), 809–816.

Rickwood, D., Deane, F. P., Wilson, C. J., & Ciarrochi, J. (2005). Young people’s help-seeking for mental health problems. Australian E-Journal for the Advancement of Mental Health, 4(3), 218–251.

Rickwood, D., Thomas, K., & Bradford, S. (2012). Review of help-seeking measures in mental health: an Evidence Check rapid review brokered by the Sax Institute. https://www.saxinstitute.org.au/wp-content/uploads/02_Help-seeking-measures-in-mental-health.pdf. Accessed 12 Oct 2017.

Rickwood, D. J., Deane, F. P., & Wilson, C. J. (2007). When and how do young people seek professional help for mental health problems? The Medical Journal of Australia, 187(7), 35–39.

Rodriguez, E. M., Donenberg, G. R., Emerson, E., Wilson, H. W., Brown, L. K., & Houck, C. (2014). Family environment, coping, and mental health in adolescents attending therapeutic day schools. Journal of Adolescence, 37(7), 1133–1142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2014.07.012.

RothÌ, D. M., & Leavey, G. (2006). Mental health help-seeking and young people: A review. Pastoral Care in Education, 24, 4–13.

Salaheddin, K., & Mason, B. (2016). Identifying barriers to mental health help-seeking among young adults in the UK: a cross-sectional survey. British Journal of General Practice, 66(651), e686–e692.

Sawyer, M. G., Borojevic, N., Ettridge, K. a., Spence, S. H., Sheffield, J., & Lynch, J. (2012). Do help-seeking intentions during early adolescence vary for adolescents experiencing different levels of depressive symptoms? Journal of Adolescent Health, 50(3), 236–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.06.009.

Talebi, M., Matheson, K., & Anisman, H. (2016). The stigma of seeking help for mental health issues: Mediating roles of support and coping and the moderating role of symptom profile. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 46(8), 470–482.

Taylor-Rodgers, E., & Batterham, P. J. (2014). Evaluation of an online psychoeducation intervention to promote mental health help seeking attitudes and intentions among young adults: Randomised controlled trial. Journal of Affective Disorders, 168, 65–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.06.047.

Vogel, D. L., Wade, N. G., & Haake, S. (2006). Measuring the self-stigma associated with seeking psychological help. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53(3), 325–337. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.53.3.325.

Vogel, D. L., Wester, S. R., Wei, M., & Boysen, G. A. (2005). The role of outcome expectations and attitudes on decisions to seek professional help. Journal of Counselling Psychology, 52(4), 459–470.

Wang, P. S., Angermeyer, M., Borges, G., Bruffaerts, R., Chiu, W. T., de Girolamo, G., Fayyad, J., Gureje, O., Haro, J. M., Huang, Y., Kessler, R. C., Kovess, V., Levinson, D., Nakane, Y., Brown, O., Ormel, M. A., Posada-Villa, J. H., Aguilar Gaxiola, J., Alonso, S., Lee, J., Heeringa, S., Pennell, S., Chatterji, B. E., S., & Ustün, T. B. (2007). Delay and failure in treatment seeking after first onset of mental health disorders in the World Health Organization’s World Mental Health Survey Initiative. World Psychiatry, 6(3), 117–185.

Wei, Y., McGrath, P. J., Hayden, J., & Kutcher, S. (2015). Mental health literacy measures evaluating knowledge, attitudes and help-seeking: a scoping review. BMC Psychiatry, 15(1), 291.

Wilson, C. J., & Deane, F. P. (2012). Brief report: Need for autonomy and other perceived barriers relating to adolescents’ intentions to seek professional mental health care. Journal of Adolescence, 35(1), 233–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.06.011.

Wilson, C. J., Deane, F. P., Ciarrochi, J., & Rickwood, D. (2005). Measuring help-seeking intentions: properties of the general help-seeking questionnaire. Canadian Journal of Counselling, 39, 15–28.

World Federation for Mental Health (2009). Mental health in primary care: enhancing treatment and promoting mental health. In World Mental Health Day. Woodbridge, Va: World Federation for Mental Health.

Wright, A., Jorm, A. F., & Mackinnon, A. J. (2011). Labeling of mental disorders and stigma in young people. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 73(4), 498–506. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.06.015.

Zachrisson, H., Rodje, K., Mykletun, A. (2006). Utilization of health services in relation to mental health problems in adolescents: A population based survey. BMC Public Health, 6, 34.

Zimet, G. D., Dahlem, N. W., Zimet, S. G., & Farley, G. K. (1988). The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of Personality Assessment, 52, 30–41.

Leavey, G., Guvenir, T., Haase-Casanovas, S., & Dein, S. (2007). Finding help: Turkish-speaking refugees and migrants with a history of psychosis. Transcultural Psychiatry, 44(2), 258-274.

Funding

This study did not receive funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GL conceived of the study and edited the manuscript. ND searched databases for relevant articles, recorded their findings and was responsible for writing the manuscript. PH and EC searched databases for relevant articles and recorded their findings. DC edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Divin, N., Harper, P., Curran, E. et al. Help-Seeking Measures and Their Use in Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Adolescent Res Rev 3, 113–122 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-017-0078-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-017-0078-8