Abstract

A large proportion of children and youth are growing up in harmful caring environments that can affect their behavioral strategies later in life. Despite the existing of an extensive literature regarding prevalence, characteristics of delinquent and criminal behavior, as well as, individual and environmental risk factors, there are gaps that remains unexplained regarding this problem. There is little evidence about what is known about the relational experiences in children and adolescents and the development of criminal and antisocial behavior. This scoping review was developed to address the matter of criminal and antisocial behavior by analyzing how this is associated with children and adolescent’s relational experiences with primary caregivers. In addition, the review examines recommendations provided in this field regarding intervention strategies to prevent or reduce the prevalence of delinquent behaviors. A total of 528 studies were identified in the databases of ProQuest, Web of Science (Core Collection) and PsychINFO. After applying the exclusion and inclusion criteria, 17 published studies were included in the analysis. The results show the presence of an association between the experience of physical and sexual abuse and the occurrence of criminal and antisocial behavior in children and adolescents. Similar findings relate to experiences of emotional care; sensitivity, warmth and closeness were identified as important protective factors for these behaviors, whereas hostility, rejection and detachment were risk factors for the development of delinquent behaviors. Further, there is a suggested need to enhance parenting skills through program activities and address the internal working model of the child/adolescent through therapy to prevent/reduce the development of criminal and antisocial behavior in these vulnerable populations. The study ends with a discussion of needed research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Attachment theory suggests that healthy development in children depends on having a responsive and sensitive attachment figure (Daniel et al. 2010). It is from this attachment relationship that the child forms an internal working model, which refers to the psychological construct through which the child views him- or herself and others and influences the affective components of behavior and interaction (Aldgate and Jones 2006; Bowlby 1969). It was established early on that delinquent behavior could originate based on a child’s experiences within his or her family; for example, mother–child separation during the first 5 years of life has been demonstrated to be associated with persistent stealing (Bowlby 1950, p. 572). Later, different styles of attachment were identified, typically categorizing infants as secure or insecure, with insecure infants commonly divided into insecure/avoidant, insecure/ambivalent and disorganized attachment styles (Ainsworth et al. 1978; Daniel et al. 2010). Disorganized attachment is often observed in children exposed to severe traumas, such as abuse, and has shown promise as a predicator of deficient social functioning and aggression development (Benum 2006). At present, developmental psychology emphasizes the impact of traumas and relational vulnerability and highlights the important function of parents as affect regulators and relational motivational systems when understanding the behavioral development of children (Nordanger and Braarud 2014; Nordanger et al. 2011; Wennerberg 2011).

Studies has examined the association between parent–child attachment, maltreatment and criminal and anti-social behavior. Experiences of neglect have been identified as a risk factor for criminal arrests during adulthood and have also been found to be associated with an increased risk of criminal behavior in children registered in the child welfare system (Grogan-Kaylor and Otis 2003; Clausen 2004). Further, antisocial tendencies in prison inmates have been found to be associated with attachment style, with inmates scoring high on avoidant attachment (Hansen et al. 2011). Additionally, an empirical study concluded that poor attachment to parents was significantly associated with delinquency in boys and girls, suggesting that the attachment relationship could be a target for interventions to prevent or reduce delinquent behavior (Hoeve et al. 2012). According to Savage (2014), parental attachment and physical aggression and violent behavior in children were found to be significantly associated, documenting, overall, that children categorized as secure had the lowest levels of aggression.

Current Study

Previous review studies in this field have more often examined various attachment styles in association with criminal and antisocial behavior. The results of such review studies provide us with important knowledge about these individuals’ inner state of attachment security. However, research regarding delinquent children and adolescents’ relational experiences with primary caregivers has yet to be summarized into a review, leaving a gap in the ability to inform and guide policies and interventional programs based on this knowledge. Given the need to identify key concepts of this population’s relational experiences and to identify gaps in this field of research, we conducted a scoping review of the literature. The aim of this study was to review and analyze the association between relational experiences with primary caregivers in children and the development of criminal and antisocial behaviors. The scoping review addressed three main research questions: (1) What are the main reported exposure variables related to caregiving experiences by children and adolescents exhibiting criminal and antisocial behaviors? (2) What recommendations does the literature provide relating to interventional strategies regarding the matter of criminal and antisocial behavior? (3) What knowledge gaps exist to guide priorities for future research and programming directions?

Methods

The methodology used in this study was a scoping review, which is a type of review used to synthetize scientific knowledge and identify research gaps (Arksey and O’Malley 2005). We developed three thematic filters related to relational experiences, criminal behavior and primary caregivers and searched the ProQuest, Web of Science, (using the Core Collection) and PsychINFO electronic databases. Within these databases and using descriptors or control vocabulary (thesaurus), thematic filters were created with MESH (Medical Subject Headings) terms and keywords. The search strings were as follows: (a) Relational experiences with the search terms “attachment, bond, bonding, closeness and connectedness”; (b) Criminal behavior with the search terms crime, delinquency, offending, violation, misconduct, antisocial behavior and externalizing behavior; (c) Primary caregivers with the search terms “parents, parental, parenting, caregiving style, maternal-infant attachment, maternal attachment, child-parent relationship, parent–child relationship, maternal sensitivity, parental sensitivity, paternal sensitivity and caregiver bonds”. In all databases, Boolean operators “AND”, “OR” and “NOT” were used to retrieve all existing literature.

In the Web of Science database, only keywords in the form of natural words were used in the topic, title and summary fields.Footnote 1 Searches were limited to the timespan between 2004 and 2014. The main inclusion criteria used in this review were empirical studies focusing on specific experiences in children and parental behavior toward the child/adolescents in terms of neglect and abuse. Both early developmental studies and criminology studies were included to assess a variety of externalizing and anti-social behavior, violence, aggression and general delinquency. Neglect and abuse have both been distinguished as subtypes of child maltreatment, with abuse divided into physical abuse and sexual abuse (World Health Organization 2015). Neglect normally refers to a passive form of abuse where the caregiver fails to meet the basic physical or psychological needs of the child, i.e., providing food or giving adequate emotional care. The term physical abuse refers to an active form of abuse involving all behaviors causing physical harm to the child. Sexual abuse is also an active form of abuse that involves all sexual activities in which a child is forced or lured to participate and can be characterized as contact and non-contact abuse (Munro 2008). The terms abuse and neglect were treated as such separate constructs in this study.

We excluded from our review; (1) studies focusing solely on the association between the child or adolescents’ attachment style/security and criminal or antisocial behavior, and (2) studies evaluating only non-parental relationships, such as aspects of peer-attachments/relationships. Additionally, (3) studies assessing the social control, religion, cultural, environmental or socio-economic factors associated with criminal and anti-social behavior were excluded. Lastly, we excluded (4) non-original studies, such as theoretical or book reviews, editorials, books, theses and studies without abstracts.

A thematic analysis was performed on each of the included studies. For the coding/categorization of these studies, themes were developed to represent some level of patterned response within the data set, as described by Braun and Clarke (2006, p. 82). During the process of coding, we focused on the study characteristics necessary to answer our research questions and, thus, we retrieved information about the participants, the measured (exposure and outcome) variables and results from included studies. Furthermore, ethical approval was not required for this study, as all studies included were in the public domain.

Results

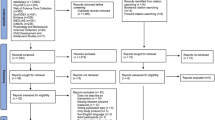

In Fig. 1, the results of the search strategy are systematically presented using the PRISMA flow chart (Moher et al. 2009). The figure outlines the number of studies that were initially identified and subsequently excluded based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. We identified 528 studies published between 2004 and 2014. Studies of non-parental relationships, family structures and socio-economic factors (n = 369), duplicate studies (n = 63), studies in other formats (n = 3) and studies without abstracts (n = 2) were excluded. An additional 43 studies were eliminated after assessing abstract eligibility, as they were not relevant to the aim of this study. Seventeen studies were selected after assessing full-text eligibility (n = 48). The following two main categories of relational experiences were identified: (1) studies evaluating the effect of physical and sexual abuse, and (2) studies evaluating the effect of emotional care.

Description of the studies

Table 1 outlines the methodological characteristics and main findings of the included studies. The studied populations were highly heterogeneous. Many studies were not based on a general population sample, instead focusing on specific groups, such as criminal offenders (Schimmenti 2014; Lahlah 2013; Kimonis 2013; Simons 2008; Wileman 2008; Palmer 2007; Kiriakidis 2006). Eleven studies evaluated both male and female participants (Schimmenti 2014; Nunes 2013; van der Voort 2013; Delhaye 2012; Sousa 2011; Ingoglia 2011; Johnson 2011; Hiramura 2010; Day 2009; Tyler 2006; Heaven 2004), whereas six studies exclusively evaluated male participants (Lahlah 2013; Kimonis 2013; Simons 2008; Wileman 2008; Palmer 2007; Kiriakidis 2006). Most studies were quantitative; however, some studies employed a cross-sectional (Nunes 2013; Lahlah 2013; Kimonis 2013; Delhaye 2012; Ingoglia 2011; Hiramura 2010; Day 2009; Simons 2008; Palmer 2007; Kiriakidis 2006; Heaven 2004) or longitudinal design (van der Voort 2013; Sousa 2011; Johnson 2011; Tyler 2006). Only one study was solely qualitative (Wileman 2008), whereas one study used mixed methods (Schimmenti 2014). Due to differences in study design, the number of individuals included in the studies ranged from 8 (Wileman 2008) to 1,007 (Johnson 2011).

Relational experiences

Physical and sexual abuse

Eight of the reviewed studies examined the relationship between physical and sexual abuse and criminal and anti-social behavior (Heaven et al. 2004; Kimonis et al. 2013; Lahlah et al. 2013; Schimmenti et al. 2014; Simons et al. 2008; Sousa et al. 2011; Tyler and Johnson 2006; Wileman et al. 2008). The measured exposure variables were child abuse, maltreatment and physical parenting, with the two terms including physical abuse, sexual abuse, and exposure to interpersonal violence/domestic violence and psychological aggression. The measured outcome variables were violent offending, sexual offending, persistent offending, psychopathy, aggression, felony and minor assault, status offenses and general delinquency.

Lahlah et al. (2013) found a direct and significant association between child abuse and severe violent offending in a probation office sample, showing that child abuse was one of the strongest predictors of severe violent offending after controlling for socioeconomic status and gender attitudes. Child abuse was constructed with the manifest and variables for sexual abuse, physical assault, psychological aggression, and exposure to intimate partner violence (Lahlah et al. 2013). When examining the impact of parental characteristics on levels of delinquency in adolescents, Heaven et al. (2004) found that physical parenting was associated with an increased probability of delinquency in boys. Physical parenting refers to the use of physical punishment by parents to control the behavior of an adolescent (Heaven et al. 2004, p. 178). By examining the developmental experiences of child sexual abusers and rapists, Simons et al. (2008) found a significant association between an offender’s own experiences of child abuse, in terms of physical abuse, sexual abuse and domestic violence, and his or her sexual offending behavior. Similarly, Sousa et al. (2011) found that exposure to child abuse, in this case, severe physical disciplining and domestic violence, was associated with increased odds of anti-social and criminal behavior. In that study, domestic violence was measured in terms of moderately severe abusive behavior by either parent, including physical violence, threats of physical harm and breaking things. Overall, the findings of that study showed that exposure to both abuse and domestic violence was more highly associated with increased anti-social behavior during adolescence than was no exposure or single exposure to either domestic violence or abuse (Sousa et al. 2011).

Other studies have found only partially significant associations between these exposures and criminal and antisocial behavior. Kimonis et al. (2013) described a significant association between physical abuse and aggression; however, a similarly significant association was not identified for the exposure of sexual abuse. Neither did they find a significant association between physical abuse and callous-unemotional traits (CU/psychopathy) in their sample, noting that this insignificant association could “explain inconsistencies in the link between psychopathic traits and history of abuse as reported in prior research” (Kimonis et al. 2013, p. 172). Tyler and Johnson (2006) reported that having experienced physical abuse was significantly associated with participating in delinquency in adolescence. However, sexual abuse was not found to be associated with delinquency in that study, which showed only an indirect effect mediated by running away.

By qualitatively assessing childhood experiences in a subsample of participants scoring high on psychopathy, Schimmenti et al. (2014) found that 7/10 had experienced relational traumas involving both physical and sexual abuse. Similarly, in another qualitative study, Wileman et al. (2008) reported that participants in their study recalled childhood experiences of both physical violence and exposure to domestic violence. With respect to child abuse, the literature provides clear assumptions of how early care environments influence the lives of children. For example, based on their sample of sexual offenders, Simons et al. (2008, p. 559) stated that “… these individuals have observed and experienced violence as a means to achieve autonomy and sexual abuse to achieve intimacy.” Similarly, regarding their sample of psychopathic offenders, Schimmenti et al. (2014, p. 267) stated that their “… states of mind regarding attachment and their adult attachment attitudes have been generated by early negative experiences and disrupted interactions with caregivers”.

Emotional care

Thirteen of the reviewed studies examined the association between perceptions/experiences of parental emotional care in children/adolescents and the development of criminal and anti-social behavior. The impact factors measured by these studies represented core elements of attachment theory, as they included dimensions of parental care and connectedness, such as warmth, empathy, sensitivity, affection, closeness and support, and parental detachment, as indicated by rejection and separation.

Kimonis et al. (2013) found that adolescent boys who reported their mothers as being less warm, affectionate and involved in their lives tended to score higher on callous-unemotional (CU) Traits. Emotional neglect was found to be most highly associated with CU traits after controlling for the influence of other childhood maltreatment measures such as sexual and physical abuse. Only measurements of maternal care were evaluated in their study. Similarly, Hiramura et al. (2010) found both aggression and delinquency to be associated with low maternal care, including lack of warmth, empathy and affection. Further, paternal overprotection, in terms of intrusion and lack of independence, was found to be an important predictor of aggressive and delinquent behavior. Impaired empathic skills were documented by both Schimmenti et al. (2014) and Kimonis et al. (2013). In another study, Kiriakidis (2006) reported that an offender’s perceptions of the quality of parental care received from his or her mother and father were associated with their belief that he or she would be able to stop offending in the future. Parenting was also found to have an impact on adolescent levels of delinquency in a study conducted by Heaven et al. (2004) in which adolescents reporting low levels of parental care (affection, warmth and nurturance) also reported high levels of delinquency. Similar associations were documented by Lahlah et al. (2013) when assessing parental connectedness, as low levels of perceived parental emotional warmth were demonstrated to have a direct association with self-reported violent delinquency in a probation sample. In terms of the effect of the perception of low parental emotional care, this association was also evident in the study conducted by Palmer and Gough (2007) in which offenders reported their parents as being less warm than did non-offenders. Similarly, Day and Padilla-Walker (2009) demonstrated the influence of parental connectedness on externalizing behavior, finding that, overall, parental connectedness is a protective factor, enhancing the development of prosocial behavior in adolescents. Furthermore, they found that fathers parenting was more consistently associated with problem behavior in adolescents, whereas maternal parenting was more consistently associated with positive behaviors in adolescents. However, Day and Padilla-Walker (2009) did not specify what it is that fathers and mothers do differently that may produce different outcomes in children’s well-being.

Some authors have only found partially significant associations between the dimensions of emotional care and criminal and antisocial behavior. Johnson et al. (2011) found that early parental support (trust, affection and closeness) was associated with lower offending during young adulthood. However, this effect was only significant when variables for peer delinquency and adolescent delinquent behavior were included in the model. As for the relationship between later parental support (beyond 17–24 years of age) and offending, Johnson et al. (2011) found a modest negative effect; thus, the presence of parental support continued to influence lower offending into young adulthood. A mediating effect was also described by van der Voort et al. (2013) when examining the longitudinal predictors of maternal sensitivity, temperament, and delinquent and aggressive behaviors in children. In that study, low levels of effortful control (self-regulation) in children were associated with increased delinquency and aggression. However, maternal sensitivity was a predictor of less delinquent behavior in adolescents after controlling for effortful control.

Other researchers have been more concerned with the effects of neglect, separation, rejection and emotional detachment on criminal and antisocial behavior. Schimmenti et al. (2014) reported experiences of neglect, rejection and separation following the loss of a parent or living in residential care. Prevalent in the study conducted by Wileman et al. (2008) were narratives of unavailability, inadequacy and disruption of parental attachments in early life, through rejection, absence, death and inconsistent father figures. Similar experiences of detachment were also identified in several of the reviewed studies. For instance, Delhaye et al. (2012) reported that delinquent youth scored significantly higher on measures of detachment, suggesting a conflictual and radical form of distancing from parents, including distrust and perceived alienation. Similarly, Ingoglia et al. (2011) found that adolescents with parental detachment tended to report higher levels of aggressive and disruptive behavior. Nunes et al. (2013) identified similar associations, documenting that high levels of parental rejection (measured as disappointment, hostility and conflictual interaction between the parent and child) were correlated with high levels of aggression and delinquency.

Intervention

Our analysis showed that only a few authors have addressed intervention and prevention efforts; specifically, only six interventional studies were included in this review. Wileman et al. (2008, p. 68) argued that knowledge regarding deficient parental relationships and childhood experiences of trauma may provide us with a greater understanding of the personal and social settings in which antisocial and criminal behaviors are grounded. Thus, they stated that prevention and management programs must be “… aimed especially at providing protective factors including the improvement of social skills and a sense of belonging and a positive environment” (Wileman et al. 2008, p. 68). Similarly, Lahlah et al. (2013, p. 1047) stated that “interventions designed to combat juvenile violence should be linked to strategies that combat violence within communities (child abuse/domestic violence)”. Kiriakidis (2006) highlighted the fact that enhancing parenting skills was important to facilitating the reduction or prevention of criminal behavior, suggesting that young offenders within correctional institutions should be offered educational programs regarding the role of parenting and socioemotional functioning in children, as these educational efforts could prevent the continuation of poor parenting practices across generations. Similarly, Kimonis et al. (2013, p. 174) suggested that interventions should be “… aimed at strengthening parental and particularly maternal affection and involvement …”. Similar considerations were evident in van der Voort et al. (2013, p. 445) study, suggesting that “sensitive parenting may therefore not only be important in early years when children are forming attachment relationships with their primary caregivers, but also in later life for the prevention or reduction of antisocial behaviors”.

Other authors have been more concerned with addressing the internal working model of offenders. Simons et al. (2008) implied that there is a need to address maladaptive strategies through therapy to prevent re-offending. Similarly, Schimmenti et al. (2014, p. 268) stated that “treatments addressing disorganized states of mind and childhood trauma during detention might reduce the risk of violent behaviors and recidivism”. Concerns regarding the importance of addressing the internal working models of the individual through interventional work were also present in the study conducted by in Kiriakidis (2006, p. 201), who suggested that “the potential possibility of concentrating on the young offenders’ attitudes and beliefs and challenging them could be a promising alternative for altering their intentions of future reoffending”.

Discussion

Primary caregivers play a vital role in the behavioral development of their children as they constitute a secure base (Bowlby 1969; Ainsworth 1978), from with a child seek support and guidance on both practical and emotional levels regarding a complexity of life occurring events. The caregiving history of abused children highlights the need to address how criminal and antisocial behavior can portray outcome variables, consequently due to inadequate relational exposure variables. In this sense, our results offer an overview of the key concepts of relational experiences associated with the development of criminal and antisocial behavior in children and adolescents, as well as, the implications it has for future research and interventional work within the field of child welfare.

This review identified several studies that found an association between childhood abuse, including specific experiences of physical and sexual abuse and domestic violence, and the development of criminal and antisocial behavior. These experiences, both separately and in combination, have been documented as significant risk factors for the development of delinquent behaviors. Furthermore, emotional care, including warmth, affection, and closeness/connectedness, and parental support have been documented as important protective factors. However, not all studies have identified a direct association between the various relevant exposure variables and the development of criminal and antisocial behavior. The following section discusses the topics of developmental traumas and affect regulation, as this have emerged as interesting mechanisms by which to understand the findings in this review. Additionally, measures of intervention, limitations and suggestions for further research will be discussed.

Within the field of developmental psychology, the term developmental trauma is commonly used when referring to complex traumas involving violence or sexual abuse that occur in interpersonal relationships (Nordanger et al. 2011). Typical symptoms and functional difficulties in children exposed to complex interpersonal traumas often include problems regulating affects, attention and behavior, and exposed children have often been portrayed as having an impaired ability to assess consequences and being “pulled” toward situations involving crime and drugs (Nordanger et al. 2011). Furthermore, the development of empathy in children can be impaired by complex traumas, including having unclear internal working models/representations of him or herself and others (Nordanger et al. 2011).

Young children have an underdeveloped ability to regulate their own emotions and are therefore dependent on the presence of sensitive adults to keep them within an optimal span of what has been referred to as a “tolerance-window”, which ranges from a state of hypo- to hyperactivity (Nordanger and Braarud 2014). Common signs of hypo- and hyperactivity have been identified as increased and decreased heartrate and respiration, respectively (Nordanger and Braarud 2014), which indicate that an individual is experiencing discomfort or dysregulation. Experiences derived from early interactive relationships with primary attachment figures are important developmental factors influencing the flexibility and span of this window (Nordanger and Braarud 2014). Parents play a significant role as affect regulators for their children. Knowledge about the experiences of abuse and neglect in children and adults can help us to understand the developmental path of criminal and antisocial behaviors. For instance, impulsiveness, aggression and externalizing behavior have been found to be typically associated with the state of hyperactivity (Nordanger and Braarud 2014). It has been hypothesized that patterned behavioral responses can develop during states of hypo- or hyperactivity and grow more extreme and persistent due to the lack of, or primitive strategies of affect regulation (Nordanger and Braarud 2014; Siegel 2012). Thus, in consideration of the development of criminal and antisocial behavior, this “tolerance window” may contribute to elucidating the mechanisms that play a role in the association between a history of developmental trauma and self-destructive behavior (Nordanger and Braarud 2014).

Our analysis identified that in the reviewed studies, warmth, affection, closeness/connectedness and support from parents constituted important protective factors, while low levels of these factors, including detachment and rejection, constituted important risk factors. Parental sensitivity has been found to be associated with less delinquency in adolescence after controlling for effortful control in children (van der Voort et al. 2013). These findings call into question whether sensitive parenting alone contributes to regulation, maintaining the “tolerance-window” within its optimal span of activation, and, ultimately, preventing the development of delinquent and aggressive behavior in children. A child’s primary attachment figure functions as a relational motivational system, and sensitive caregiving influences the development of emotional bonds and closeness in children (Wennerberg 2011). With respect to the documented associations between the aspects of emotional care and criminal and anti-social behavior, researchers have typically used attachment theory to substantiate the meaning of this relationship. Similar to exposure to relational traumas involving child abuse, a primary caregiver’s emotional availability and sensitivity can influence behavioral development in children. Day and Padilla-Walker (2009) reported that maternal connectedness was positively associated with prosocial behavior in adolescents after controlling for self-regulation. Furthermore, Johnson et al. (2011) found parental support to be associated with lower levels of delinquency, describing this effect as persistent even in models considering peer influence. Thus, sensitive and supportive parenting seems to function as a “buffer” that reduces the risk of a child or adolescent from taking a developmental path that involves criminal and antisocial behavior. As Johnson et al. (2011, p. 793) suggested, “… poor relationships with parents are related to a greater likelihood of associating with deviant peers, which in turn increases offending”. Additionally, Johnson et al. stated that, “This is consistent with a social learning perspective, which argues that parents help to shape the peer networks of their offspring and limit the time they spend with deviant others” (Johnson et al. 2011, p. 796).

Emotional neglect often involves ignoring or overlooking signals from children and not responding to their contact attempts in a sensitive manner (Kvello 2010). Previous review studies have often assessed attachment style, and atypical attachment styles were frequently identified in these samples (Savage 2014; Hoeve et al. 2012). In our review Wileman et al. (2008) identified indications of an avoidant attachment style and primary group deficiency in their sample, with primary group deficiency involving having an absent parent or being left uncared for on several occasions. These results were in accordance with findings indicating that children with insecure/avoidant attachment typical have perceived their mothers as cold or rejecting (Daniel et al. 2010). In our study Schimmenti et al. (2014) documented disorganized attachment styles in their sample and stated that early attachment relationships were important to understanding the psychological origin of violent behavior, which coincided with findings indicating disorganized children to often be aggressive and controlling (Daniel et al. 2010). Children with an avoidant attachment style typically feel unloved and may have negative expectations about others, whereas ambivalent children tend to devaluate themselves and view others as unreliable (Daniel et al. 2010). Obtaining knowledge about attachment relationships and their mental representations in children can therefore be a viable way to understand the development of criminal and anti-social behavior. Still, the extent to which an unloved child has a reduced ability to love him- or herself and whether devaluation prevents a child from living up to his or her actual potential remain the subjects of mere speculation. However, to the extent that we make these assumptions, emotional neglect can be explained as resulting in relational vulnerability and reflect an individual’s ability to seeks support from others (Wennerberg 2011).

Based on the documented associations between experiences of physical and sexual abuse and emotional neglect, and the development of criminal and antisocial behavior it has been suggested that parenting skills needs to be enhanced. It has been argued that interventional actions should be implemented in the form of interventional programs and individual therapy, thus focusing on both transgenerational aspects and the internal working model of the offender when explaining the development of delinquent behaviors. Clearly, individual therapy has a focus on enhancing an individual’s awareness regarding their experiences of developmental traumas and determining how the meaning subscribed to these traumas influences their behavioral strategies as they create mentalized images of themselves and others. Furthermore, this self-awareness can be a promising strategy to approach some aspects of affect regulation, thus helping the individual to develop strategies that increase the span of his or her tolerance window.

Limitations

Since the method used was a scoping review, an in-depth assessment of the quality of the reviewed studies was not conducted. Although no structured approach was used to evaluate the quality it is noted that all the included articles were published in peer-reviewed journals. This study was limited to articles published during 2004–2014, thereby leaving grey-literature and early developmental studies unaccounted for. Most of the reviewed studies documents an association between factors of abuse and neglect and criminal and antisocial behavior. However, heterogeneity is present in these results as some studies have only partially documented this association.

Some researchers have evaluated information about experiences of child abuse, and others have evaluated different experiences of emotional neglect. However, only two studies (Kimonis et al. 2013; Lahlah et al. 2013) have the strength of comparability relating to the exposure variables as they have included both types of exposure, reporting on its associations relating to the development of criminal and antisocial behavior. This scoping review indicates by its approach of attachment theory and developmental trauma psychology that the aspects of “internal working models” and the “tolerance window” can contribute to understanding the documented associations between childhood experiences of abuse and neglect by, theoretically, substantiating that there is a link between past and future. However, only by the execution of longitudinal studies can we make these assumptions with some degree of certainty. This calls to note the limitation that most of the studies in this review were cross-sectional. Another important limitation of the current review is that the extensive literature search did not result in many qualitative studies reporting on how children and adolescents themselves, psychologically speaking, experienced being abused or neglected. Developmental traumas have been described as occurring during the meeting between a specific objective event and an individual’s mental interpretation of such an event (Wennerberg 2011). It is difficult to say how important physical or sexual abuse or emotional neglect are in the development of criminal and antisocial behavior. Meaning that it is not enough to uncover what the child or adolescent has experienced; we need to know how they subscribe meaning to these experiences to be able to widen our knowledge about these documented associations. Only two of the studies in this scoping review (Schimmenti 2014; Wileman 2008) have the strength of the qualitative design needed to provide in-depth knowledge regarding the way children and adolescents subscribe meaning to their lived experiences of abuse and neglect.

Further research

By systematically reviewing through the method of a scoping review we can forward several implications for future research. From our results, we end up with important implications for future research. Emotional neglect showed a stronger association with delinquent behavior than did child abuse, including measures of sexual and physical abuse, in the reviewed studies of Kimonis et al. (2013) and Lahlah et al. (2013). However, the information reviewed was not sufficient to draw the generalized conclusion that child abuse has less influence in this regard. Thus, there is a need for future research to examine the two dimensions of relational experiences simultaneously to better draw conclusions regarding the development of criminal and antisocial behavior. This will allow for comparability which represents a limitation in this field of research today. The availability of qualitative studies was almost non-existent, providing us with minimal knowledge of how the delinquent adolescents themselves make casual interpretations regarding their criminal pathway and their lived experiences of maltreatment. It is therefore urged that future research address this gap by conducting extensive qualitative research regarding this matter. Qualitative based research on the subject could substantiate the existing evidence based research with important narratives, possibly coinciding with the existing research. Furthermore, qualitative and quantitative research could provide greater grounds for developing efficient interventional programs and greater assurance of their successfulness as it is empowered by the explicitly of what the adolescent think he or she needs.

Our review also documented that there exists a tendency to differentiate between mothers and fathers regarding the matter of parenting, typically subscribing parenting by the mother with the emotional characteristics and leaving paternal influence in this matter unaccounted for. The results of Day and Padilla-Walker (2009) study implicates that a gender perspective in future research can be important. Future research should examine this differentiation by assessing dimensions of both maternal and paternal emotional care more explicitly and its association with criminal and antisocial behavior. This is of importance as such associations may report on a need for addressing the question of interventional strategies accordingly to the possible influence of a gender perspective. Our theoretical point of departure for this review was attachment theory. However, our results also indicated that a social learning perspective (Bandura 1977) could be a viable theoretical perspective, as the current literature also provided evidence of criminal and anti-social behavior in association with both generational transition issues and peer influence. Consequently, future reviews regarding the development of criminal and antisocial behavior should be expanded to analyze the associations between gender, generational and environmental factors. Such meta- analyses may address this gap in the research, further ensuring that possible meditating effects are not overlooked or unaccounted for regarding this matter.

Conclusion

Children and youth develop through various forms of interpersonal relationships, with the child-parent attachment relationship being of great importance of their emerging into adulthood. This scoping review offers insight into how the literature addresses the issue of criminal and antisocial behavior, as it is associated with relational experiences between children and adolescents and their primary caregivers. Under the framework of attachment theory and relational vulnerability, this review provides an overview and understanding of the casual implications that the literature provides regarding the development of such behaviors. To date, this article provides the first review regarding this matter, summarizing both the state of current research, and gaps in this research field, as well as implications for interventional efforts. Lived experiences of maltreatment in terms of abuse and emotional neglect have an impact on the behavioral development of children and youth. Child abuse has been highlighted as a strong predictor for delinquent behaviors and its effect is also transferable when it comes to aspects of emotional care.

The results of this review provide an awareness of how children and youth depend on safe, caring environments so that they can emerge into adulthood with the belief that they can seek support in others, and that they are provided strategies for doing so through the means of safety and adequate affect regulation. Recommendations for interventional work reflects on this, as it is urged that educational parental programs focused at enhancing parenting skills can be a viable way to facilitate the reduction or prevention of criminal and antisocial behavior. Addressing matters of child abuse and neglect constitutes the daily practices for the professionals within social and child welfare institutions. Thus, this review underscores the need to raise awareness of the complexity of this problem, including the need to address the narratives relating to the developmental traumas of children and youth when constructing interventional programs and policies.

Notes

ts = (attachment or bond or bonding or closeness or connectedness) AND ts = (crime or delinquency or offending or violation or misconduct or “antisocial behavior or “externalizing behavior) AND ts = (parents or parental or parenting or “caregiving style” or “maternal-infant attachment” or “maternal attachment” or “child-parent relationship” or “parent–child relationship” or “maternal sensitivity” or “parental sensitivity” or “paternal sensitivity” or “caregiver bonds”) NOT ts = (“peer attachment” or “attachment to friends” or environmental or community or “social bonds” or neighborhood)) indexes = SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI Timespan = 2014–2004 years.

References

Ainsworth, M. D. S., Belhar, M. C., Waters, E., & Wall, S. (1978). Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation. Hillsdale N.J: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Aldgate, J., & Jones, D. (2006). The place of attachment in children’s development. In J. Aldgate, D. Jones, W. Rose & C. Jeffery (Eds.), The developing world of the child. London and Philadelphia: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. doi:10.1080/1364557032000119616.

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory: Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall.

Benum, K. (2006). Når tilknytningen blir traumatisert. En psykologisk forståelse av relasjonstraumer og dissosiasjon. In M. Jakobsen (Ed.), Dissosiasjon og relasjonstraumer. Integrering av det splittede jeg. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

Bowlby, J. (1950). Research into the origins of delinquent behaviour. The British Medical Journal, 1(4653), 570–573.

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss volume 1: Attachment. England: Penguin Books.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thmatic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in Psychology, 3(77), 77–101.

Clausen, S.-E. (2004). Har barn som mishandles større risiko for å bli kriminelle? Tidsskrift for Norsk psykologforening, 41, 971–978.

Daniel, B., Wassel, S., & Gilligan, R. (2010). Child development for child care and protection workers (2 ed.). London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Day, R. D., & Padilla-Walker, L. M. (2009). Mother and father connectedness and involvement during early adolescence. Journal of Family Psychology, 23(6), 900–904.

Delhaye, M., Kempenaers, C., Burton, J., Linkowski, P., Stroobants, R., & Goossens, L. (2012). Attachment, parenting, and separation-individuation in adolescence: A comparison of hospitalized adolescents, institutionalized delinquents, and controls. The Journal of Genetic Psychology: Research and Theory on Human Development, 173(2), 119–141.

Grogan-Kaylor, A., & Otis, M. D. (2003). The effect of childhood maltreatment on adult criminality: A tobit regression analysis. Child Maltreatment, 8(2), 129–137. doi:10.1177/1077559502250810.

Hansen, A. L., Waage, L., Eid, J., Johnsen, B. H., & Hart, S. (2011). The relationship between attachment, personality and antisocial tendencies in a prison sample: A pilot study. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 52, 268–276. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9450.2010.00864.x.

Heaven, P. C., Newbury, K., & Mak, A. (2004). The impact of adolescent and parental characteristics on adolescent levels of delinquency and depression. Personality and Individual Differences, 36(1), 173–185.

Hiramura, H., Uji, M., Shikai, N., Chen, Z., Matsuoka, N., & Kitamura, T. (2010). Understanding externalizing behavior from children’s personality and parenting characteristics. Psychiatry Research, 175(1–2), 142–147. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2005.07.041.

Hoeve, M., Stams, G. J., van der Put, C. E., Dubas, J. S., van der Laan, P. H., & Gerris, J. R. (2012). A meta-analysis of attachment to parents and delinquency. Journal of abnormal child psychology, 40(5), 771–785. doi:10.1007/s10802-011-9608-1.

Ingoglia, S., Lo Coco, A., Liga, F., & Grazia Lo Cricchio, M. (2011). Emotional separation and detachment as two distinct dimensions of parent-adolescent relationships. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 35(3), 271–281. doi:10.1177/0165025410385878.

Johnson, W. L., Giordano, P. C., Manning, W. D., & Longmore, M. A. (2011). Parent–Child Relations and Offending During Young Adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40(7), 786–799.

Kimonis, E. R., Cross, B., Howard, A., & Donoghue, K. (2013). Maternal care, maltreatment and callous-unemotional traits among urban male juvenile offenders. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42(2), 165–177. doi:10.1007/s10964-012-9820-5.

Kiriakidis, S. P. (2006). Perceived parental care and supervision—relations with cognitive representations of future offending in a sample of young offenders. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 50(2), 187–203. doi:10.1177/0306624x05278517.

Kvello, Ø. (2010). Barn i risiko. Skadelige omsorgssituasjoner. Oslo: Gyldendal Norsk Forlag.

Lahlah, E., Lens, K. M. E., Bogaerts, S., & van der Knaap, L. M. (2013). When love hurts Assessing the intersectionality of ethnicity, socio-economic status, parental connectedness, child abuse, and gender attitudes in juvenile violent delinquency. Child Abuse & Neglect, 37(11), 1034–1049. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.07.001.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J & Altman, DG, The PRISMA Group (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 6(7): e1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097.

Munro, E. (2008). Effective child protection. London: Sage Publications.

Nordanger, D. Ø., & Braarud, H. C. (2014). Regulering som nøkkelbegrep og toleransevinduet som modell i en ny traumepsykologi. Tidsskrift for Norsk psykologforening, 51(7), 530–536.

Nordanger, D. Ø., Braarud, H. C., Albæk, M., & Johansen, V. A. (2011). Developmental trauma disorder: En løsning på barnetraumatologifeltets problem? Tidskrift for Norsk Psykologiforening, 48(11), 1086–1090.

Nunes, S. A. N., Faraco, A. M. X., Vieira, M. L., & Rubin, K. H. (2013). Externalizing and internalizing problems: Contributions of attachment and parental practices. Psicologia-Reflexao E Critica, 26(3), 617–625

Palmer, E. J., & Gough, K. (2007). Childhood experiences of parenting and casual attributions for criminal behavior among yonug offenders and non-offenders. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 37(4), 790–806.

Savage, J. (2014). The association between attachment, parental bonds and physically aggressive and violent behavior: A comprehensive review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 19(2), 164.

Schimmenti, A., Passanisi, A., Pace, U., Manzella, S., Di Carlo, G., & Caretti, V. (2014). The relationship between attachment and psychopathy: A study with a sample of violent offenders. Current Psychology, 33(3), 256–270. doi:10.1007/s12144-014-9211-z.

Siegel, D. J. (2012). Developing mind (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Publications.

Simons, D. A., Wurtele, S. K., & Durham, R. L. (2008). Developmental experiences of child sexual abusers and rapists. Child Abuse & Neglect, 32(5), 549–560. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.03.027.

Sousa, C., Herrenkohl, T. I., Moylan, C. A., Tajima, E. A., Klika, J. B., Herrenkohl, R. C., & Russo, M. J. (2011). Longitudinal study on the effects of child abuse and children’s exposure to domestic violence, parent–child attachments, and antisocial behavior in adolescence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 26(1), 111.

Tyler, K. A., & Johnson, K. A. (2006). A longitudinal study of the effects of early abuse on later victimization among high-risk adolescents. Violence and Victims, 21(3), 287–306.

van der Voort, A., Linting, M., Juffer, F., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., & van Ijzendoorn, M. H. (2013). Delinquent and aggressive behaviors in early-adopted adolescents: Longitudinal predictions from child temperament and maternal sensitivity. Children and Youth Services Review, 35(3), 439–446. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.12.008.

Wennerberg, T. (2011). Vi er våre relasjoner- om tilkytning, traumer og dissosiasjon. Oslo: Arneberg.

Wileman, B., Gullone, E., & Moss, S. (2008). Juvenile persistent offender, primary group deficiency and persistent offending into adulthood: Qualitative analysis. Psychiatry Psychology and Law, 15(1), 56–69. doi:10.1080/13218710701874005.

World Health Organization. (2015). Child maltreatment. Retrieved March 9, 2015, from http://www.who.int/topics/child_abuse/en/.

Acknowledgements

The study was funded by the Regional Knowledge Center for Children and Youth in Norway [RKBU-Vest-]. The author gratefully acknowledges the assistance of the co-authors Gaby Ortiz-Barreda and Ragnhild Hollekim for their ongoing guidance and all valuable advices on methodological matters and theoretical inputs when drafting this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Stormo, J.J., Ortiz-Barreda, G. & Hollekim, R. Relational Experiences as Explanatory Factors for the Development of Criminal and Antisocial Behavior: A Scoping Review. Adolescent Res Rev 2, 213–227 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-016-0050-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-016-0050-z