Abstract

Adolescents with disabilities face many challenges common to their typically developing peers. However, the ways that they resolve them may differ. The focus of this narrative overview was to summarize results from the disabilities in adolescence literature, highlight common research directions, evaluate the overall big picture of this literature, and draw conclusions based on general interpretations. Evidence suggests that the literature in this field of study is lacking. Suggestions for improvement include increasing the number of studies that focus specifically on adolescence across the various types of disabilities, establishing a theoretical base to anchor research, forming cohesion across disabilities among researchers, and taking a comprehensive approach to intervention studies. By addressing these issues in future research, scholarly knowledge will be increased, but more importantly, the lives of young people with disabilities can be greatly enhanced.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Almost 12 % of the U.S. population has been diagnosed with a disability (US Census Bureau 2010). Of children 3–17 years of age, about 15 % have one or more developmental disabilities including autism spectrum disorder, cerebral palsy, intellectual disability, and other developmental delays (Boyle et al. 2011). The term disability often serves as an umbrella expression, highlighting physical impairments—problems in body function or structure, activity limitations—difficulties in executing a task or action, and participation restrictions—constraints in functioning in life situations. The complexity of the construct extends beyond the subcategorizations of disability (e.g., intellectual, developmental, cognitive, physical) to reflect not only the features of an individual’s body and/or mind, but also the interaction between these features and the individual’s environment, including cultural implications associated with a given disability within the society in which an individual lives (Vygotsky 1978). The societal and cultural views of disability can take on additional meaning during the adolescent years (see Al-Kandari 2015; Morin et al. 2013; Scior et al. 2013; Siperstein et al. 2011).

Adolescence is a time of marked biological changes, cognitive adjustments, and social transitions. While not all youth experience these transformations equally, disproportionately more young people with disabilities are prone to challenges than their typically developing peers. Understandably, most adolescents with disabilities desire to have developmental experiences and social opportunities similar to their typically developing peers. However, when struggles related to their disabilities make it more difficult, or impossible, to participate in social activities at the same rate and level as their peers, negative psychosocial outcomes like stress and loneliness can result (Asher and Paquette 2003; Locke et al. 2010; Whitehouse et al. 2009). The focus of this narrative overview is to summarize the empirical findings that represent our field’s understanding of adolescence and disabilities and to highlight common directions in the research. Our purpose is to provide insight into how societal views of disability within the adolescent population relate to empirical evidence of development for these youth.

Current State of Adolescents with Disabilities

Before examining the developmental literature, it may be beneficial to briefly review the current state of societal efforts, including social policy, with regard to adolescents with disabilities. The two most salient areas implicate education, and academic-peer interactions in educational settings.

Educational Focus on Integration and Inclusion

The current emphasis to provide educational opportunities for adolescents with disabilities is on integration and inclusion. Strengthened by the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001, the purpose of the reissued Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (2004) was to ensure that all students receive comparable education in the least restrictive environment regardless of intellectual, physical, or emotional exceptionality. Inclusion occurs at various levels and in diverse contexts throughout the school day based on the individual needs of the learners and the availability of school resources. Positive consequences of inclusion allow students with special needs to attend the same schools as siblings and neighbors, interact in general education classrooms with chronological same-aged classmates, have individualized and relevant learning objectives (IEPs), and receive the support necessary to learn (e.g., special education and related services). Integration should occur on a regular basis for as much of the school day as possible, as if the inclusion students did not have a disability (Billingsley et al. 2014).

Greater Acceptability and Opportunities

Along with the inclusion emphasis in academics, current social policy focuses on providing youth with disabilities more opportunities to interact with their peers. Educators are encouraged to integrate students with disabilities in both academic and non-academic settings to maximize interactive experiences with all their peers (Ryndak et al. 2000). As a result, greater acceptability and involvement of individuals with disabilities across various activities, including participation in physical activity (Murphy and Carbone 2008; U.S. Department of Education 2011), will not only increase the overall health of individuals with disabilities, but will also allowing interactions to occur between adolescents with disabilities and their typically developing peers outside of academic settings. Encouragingly, a variety of programs promoting these engagement opportunities exist (i.e., Aggies Elevated 2015; Langtree 2015; Think College 2016; Unified sports 2016).

Societally, we are making strides toward integrating adolescence with disabilities with their typically developing peers. Significant and important work remains nonetheless. For example, one potential problem, identified by scholars, is that many of the current approaches are disability specific; programs are created for a particular disability (e.g., Down Syndrome, Autism Spectrum Disorder, Cerebral Palsy, etc.), which make each approach strong and applicable for some disabilities to the exclusion of other disabilities. Not only is this occurring in the practical and applied aspect of adolescents with disabilities, the literature in the field may be following a similar pattern—focusing narrowly on specific disabilities and missing potential generalization across disabilities.

Purpose of the Review

Not unlike their typically developing peers, adolescents with disabilities are faced with many challenges associated with the adolescent years. The purpose of this narrative overview was to summarize the disabilities in adolescence literature, highlight common research directions, evaluate the overall big picture of this literature, and draw conclusions based on general interpretations. This review will systematically explore areas that most directly impact development in adolescence (family, friends/peers, school/extracurricular activities, technology, bullying, and psychosocial development). We chose to focus on these areas because of their salience in the lives of adolescents with disabilities, their potential influence in helping this population navigate adolescence and prepare for the transition to adulthood, and because they are the most widely studied areas in typically developing adolescents. We note that there are many other areas that relate to the development of adolescents with disabilities (e.g., sexuality, offending, independence, social interaction, etc.), however, we feel these are nested in the areas examined in this review. The anticipated result of the review is to consider whether the literature is promoting greater understanding of adolescents with disabilities or if the field is inadvertently disabling the adolescent disability literature. A second goal of this review is to highlight the extent to which researchers are collaborating across areas of disability to enhance independence and growth across disabilities or if the lines of inquiry are overtly disability specific (i.e., focused only on one type of disability).

Methods

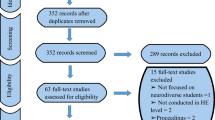

Source of Information

A search of the disability and adolescence literature was conducted using the following databases: EBSCOhost, Google Scholar, and PsychInfo. Manual searches of disability specific journals (Research in Developmental Disabilities; Journal of Intellectual Disability Research; American Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities [formerly American Journal on Mental Retardation]; The Journal of Special Education; Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders) were also conducted. Finally, lines of inquiry followed for reference lists spawned from initial searches, along with targeted searches of prominent researchers and programs.

Search Terms and Selection Criteria

The research review on adolescence and disabilities focused primarily on studies published from the years 2000–2016, in order to understand the current state of the field of research in the area. Keywords searched included disability, adolescence/adolescent, teenager/teen, intellectual disability, developmental disability, family, parents, siblings, psychosocial development, friends and peers, school, relationship, special education, technology, disability sport, identity formation, bullying, attachment, parental attachment, friend and peer attachment, autonomy, self-esteem, inclusion. Search terms were entered independently, combined and meshed. Studies were reviewed based on title, abstract, and article content. Beyond the year limitation, criteria for article selection for inclusions in the full review included: (a) studies that used at least some participants who were in the adolescent developmental stage (~9 to ~21 years of age), (b) focused on some type of disability (including intellectual, developmental, physical, cognitive, or a combination of disabilities [dual-diagnosis]), and (c) emphasized family relationships, friend and peer interactions, school, technology, bullying, and/or psychosocial development of adolescents with disabilities rather than interventions. Both quantitative and qualitative studies were included in the review.

Analysis

We began the initial search for articles with a general ‘adolescent with disabilities’ query. Relevant articles were included that matched the population criteria. Results were further whittled, by excluding research that focused on areas outside of the topics identified for the review. Once articles were determined as a quality fit for the review, each article was reviewed for specific findings related to adolescence and disability within each area of focus (family, friends and peers, school, technology, extracurricular activities, bullying, and psychosocial developmental aspects). From this analysis, main findings were extracted, synthesized, and combined by common themes into narrative form to promote understanding of the current strengths and weaknesses of the literature in the field.

Results

Family Relationships (Bi-directional Impact)

Family relationships play an important development role for adolescents with disabilities. As these young people seek to form an identity and explore relationships outside of the family, adolescents with disabilities rely heavily on their family. It is important to underscore the bi-directional impact of these relationship, especially with this subpopulation of adolescents; the individual with disabilities will impact the family while the family will impact the individual with disabilities. All family members play a role, but parental and sibling responsibilities differ noticeably in the life of the adolescent with disabilities.

Parents

An individual with disabilities’ transitioning from childhood to adolescence poses new challenges for parents, particularly mothers. As the adolescent develops an independent sense of self, parents often explore how to best help their child with the transitions. This assistance can include ways to teach the adolescent with disabilities about potential limitations of their disability, ways to grant and limit freedom to their child, and ways to redefine their roles as parents. Even though extensive empirical literature on identity development and autonomy granting exists for typically developing adolescents, the same is not true for adolescents with disabilities. It seems unrealistic to assume that parents of adolescents with disabilities should look to the typically developing literature for guidance in raising a child with disabilities. Exploration in the role of the family in psychosocial development, specific to adolescents with disabilities, seems needed. Unfortunately, because of the difficulties associated with the psychosocial development process for young people with disabilities, most of the research on parent–child relationships with this population focuses on negative outcomes associated with it, such as stress, rather than on family’s role on the developmental process itself.

Empirical studies on the family’s role for development in adolescents with disabilities are relatively new and abundantly skewed toward the examination of parental stress. This body of literature makes a clear case that disabilities can have an overall negative impact on parents’ psychological wellbeing and family functioning. Because they often fill the role of primary caregiver, mothers are especially vulnerable to unique types of parenting stress (Ulus et al. 2012). To illustrate this point, Ekas and Whitman (2010) found that adolescents with autism spectrum disorder exhibited a more challenging profile of autism spectrum disorder symptoms, cognitive impairments, and co-occurring behavioral problems than younger children with autism spectrum disorder. Parents, especially mothers, of youth and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder, were at particularly high risk for poor psychological well-being as compared to parents of children without disabilities (Ekas and Whitman 2010). To further underscore this point, Hartley and Schultz (2015) sought to identify which support needs were important to mothers, compared to fathers, of children with autism spectrum disorder. Using a sample of 73 married couples of children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder, researchers interviewed the parents, administered a 54-item questionnaire, and had parents complete a 10-day online dairy to assess important support needs that were being met and that remained unfulfilled. They found that, compared to fathers, mothers of children with autism spectrum disorder endorsed a significantly higher number of important support needs, and indicated significantly more needs remaining unmet (Hartley and Schultz 2015).

Researchers have identified similar negative outcomes for parents of adolescents with other disabilities. Parents of adolescents with Mild to Borderline Intellectual Disabilities more often perceive their parenting behavior as flawed, suggesting that a sense of competence, among these parents, may be lower than for other parents. The added presence of negative externalizing behaviors, common in adolescents diagnosed with Mild to Borderline Intellectual Disabilities, further contributed to a reduced sense of parental competence, less acceptance of the child, and diminished closeness with the child (Schuiringa et al. 2015). The view of their parenting as flawed is further perpetuated as parent–child relations are realigned, including possible adjustments in role responsibilities and decision-making, during the complex process of transitioning from childhood to adolescence and then from adolescence to young adulthood (Betz et al. 2015).

Parents of adolescents with intellectual disabilities also experience high levels of stress and/or mental health problems, which can be related to subjective factors such as feeling social isolation and life dissatisfaction. Additionally, they may experience disappointment, embarrassment, shame, and guilt as they recognize that their child may never reach the goals they had envisioned for them. These negative feelings result from both logical and illogical beliefs that they caused their child to have disabilities (Azeem et al. 2013). Communication issues for parents of adolescents with intellectual disabilities are frequently linked to this stress. Jones et al. (2014) found that talking to an adolescent about difference and disability is a difficult task for parents. Many struggle to grasp the level of content and optimal timing of interactions with their child with intellectual disabilities. As a result, much of the communication within the parent–child dyad ends up being reactive instead of proactive, often occurring after the adolescent was bullied, or as an explanation for why the child could not participate in an activity with their typically developing peers (Jones et al. 2014).

Throughout this literature, there is little mention of the positive aspects of parenting adolescents with disabilities. A good start to changing this trend came from Mitchell and Hauser-Cram (2010) as they explored ways to help parents develop healthy relationships with their adolescent with disabilities. They examined the role that early-parenting stress and child-behavior problems play in the future mother-adolescent and father-adolescent relationships. They concluded that support and assistance to reduce stress, for both parents, during the early childhood year could benefit both parents in their future relationship with their adolescent child with disabilities. Further, they determined that there is a pressing need for emphasis on early intervention and education programs to help families, parents, and children manage and diminish problem behaviors, toward enhancing ensuing parent-adolescent relationship (Mitchell and Hauser-Cram 2010).

The current research, across disabilities, demonstrates that parents experience stress as they seek to comprehend their child’s disability, particularly mothers who more often assume a caregiving role. As parents endeavor to find the appropriate way to integrate themselves and their children with disabilities into the community, stress induced fears and uncertainty can lead to strained communication in the parent–child relationship and reduced social interaction for the child. However, understanding how to communicate with their child about their disability, including differences and limitations, in conjunction with early intervention and education programs, help parents and families to successfully navigate the adolescent period.

Siblings

An individual with disabilities’ transition into adolescence relates to sibling relationships as well. Similar to typically developing sibling dyads, several factors play into the sibling relationship quality and the closeness that adolescents with disabilities have with their siblings. Typically developing siblings’ understanding of their sibling’s disability and its implications impacts the level and quality of relationship. As the individual with disabilities gets older, the siblings, those younger and older, often take on a parent/caretaker role and begin to realize that it might 1 day be their responsibility to care for their brother/sister.

Researchers posited that there may be more similarities than difference between typically developing sibling dyads and dyads that include a sibling with an intellectual disability (Doody et al. 2010). They contended that the primary difference between typically developing sibling dyads (n = 123) and those with a sibling with a disability (n = 63) was evidenced as the older sibling took on adult roles and responsibilities. It is important to acknowledge the similarities between typically developing sibling dyads and those dyads with an adolescent with disabilities. However, the complexities of the relationship within a typically developing-disability dyad is related to the type and severity of the disability as well as added dimensions such as behavioral and health concerns. Some initial work is underway to illustrate these differences.

Smith et al. (2015) sought to understand both the impact of autism spectrum disorder severity on sibling resources (relationship networks, coping strategies, and psychosocial adjustment) and whether autism spectrum disorder severity and typically developing adolescent sibling resources predicted a sense of coherence—an individual’s understanding of a stressor, manageability of it, and whether there is an emotional investment in adjusting to it. Using a sample of 96 11–18 years-old typically developing siblings, these researchers employed a 217-item questionnaire to examine psychosocial adjustment, supportive relationships, coping strategies, and sense of coherence. They found that both autism spectrum disorder severity and the resources of the typically developing adolescent sibling influenced a sense of coherence in typically developing adolescent siblings of individuals with autism spectrum disorder (Smith et al. 2015). However, they acknowledged both design and methodology limitations that made inferring causal relationships and extending generalizability, particularly to minority and lower socioeconomic status groups difficult.

Pollard et al. (2013) examined anxiety for Down Syndrome and autism spectrum disorder sibling relationships. They found that reporting more negative interchanges within the sibling relationship was related to higher levels of anxiety, while fewer negative interchanges decreased anxiety levels in typically developing siblings. Additionally, sibling relationship quality moderated the relation between sibling disability type and anxiety (Pollard et al. 2013). For adolescents with intellectual disabilities, mothers reported more warmth in the sibling relationship for same-sex dyads, and same-sex siblings reported more positive sibling interactions (Begum and Blacher 2011).

Additional research focusing on sibling relationships and disabilities has shown a positive directional effect for both members of the dyad. In fact, acknowledging negative outcomes associated with a sibling with disabilities, many typically developing siblings indicated that the positives outweighed the negatives (Caplan 2011). Most siblings sought to accentuate the positive experiences they have with their sibling with disabilities and downplay the negative incidents, indicating that they would not change anything about their experience, even though they recognize the challenges it presents to the family (Graff et al. 2012).

Beyer (2009) reported that typically developing siblings of individuals with autism spectrum disorder have either comparable or more favorable relationship quality than typically developing siblings without a family member with disabilities. Relationship characteristics in typically developing-autism spectrum disorder dyads include high levels of admiration, tolerance, empathy, and selflessness coupled with low levels of both quarrelling and competition (Ferraioli and Harris 2010). These findings suggest that siblings of individuals with autism spectrum disorder have supportive relationships and these relationships may contribute to the typically developing sibling’s overall adjustment and wellbeing. Indeed, siblings of individuals with disabilities often are more resilient and have deeper, more developed compassion for others compared to their peers without a family member with disabilities (Caplan 2011).

Begum and Blacher (2011) concluded that relationships between siblings, particularly same-sex dyads, are important to adolescents with intellectual disabilities. Social opportunities are less prevalent for youth with disabilities than for typically developing youth (Tonkin et al. 2014). Given the limited social sphere, sibling relationships provide an opportunity for adolescents with intellectual disabilities to learn requisite skills and appropriate behaviors through observation and experience. Sibling relationships also socialize and prepare adolescents with intellectual disabilities for social functioning in other peer contexts, as the sibling provides opportunities to experiment with behaviors and learn from observed interactions between the typically developing sibling and others (Begum and Blacher 2011). Further, the older sibling, without intellectual disabilities, is likely to assume a caretaking role, particularly if the older sibling is female. As a result, the sibling is more likely to report feeling greater levels of warmth/closeness and lower levels of conflict compared to a typically developing adolescent sibling dyad (Cuskelly 2016; Floyd et al. 2009).

While researchers have found positive outcomes in sibling relationships when one member of the dyad has a disability, the bi-directional impact on the typically developing sibling can also have a negative connotation. As the sibling of a person with autism spectrum disorder, for example, develops through adolescence and early adulthood, her/his cognitive capacity increases to understand the possible causes of a disability and to recognize the impact of the symptoms on all family members. Ferraioli and Harris (2010), studying the impact that autism spectrum disorder has across the developmental lifespan, found that as a knowledge of the causes and potential impacts of disabilities increased during adolescence, new challenges emerged. For example, the sibling may feel an increase of sadness and disappointment as she/he can now anticipate the long-term impact of the disability on the sibling with disabilities’ life and realize how limited that life may be. As the typically developing sibling ages, she/he develops a sense of duty for the welfare of their sibling with disabilities, realizing that once their parents die, the responsibility to care for her/his sibling becomes hers/his. Beyond the current sibling situation, the typically developing sibling also recognizes the possibility of transmitting to his/her own children the genetic material associated with the disabilities, which may cause the sibling to ponder whether he/she really wants to have children (Ferraioli and Harris 2010).

Owing to their experiences growing up with an adolescent sibling with disabilities, the typically developing sibling may struggle more than normal with developmental tasks of the early college years (Caplan 2011). Compulsive altruism often influences normal developmental dilemmas associated with college, such as leaving home, forming new relationships, and making vocational choice in characteristic ways. These siblings often serve as a support for their parents and may feel like they have abandoned their family to pursue a college education or may feel guilt and selfishness for their choice. Additionally, they may seek to take on exaggerated responsibility (much like they do with their sibling with disabilities) for the difficulties of roommates, friends, and peers. Lastly, they may choose a vocation based on parental wishes instead of their own desire to avoid disappointing their parents. This is especially true when they feel that their parents have already experienced enough disappointment as a result of their sibling with disabilities incapability to reach dreams and goals (Caplan 2011).

Further negative feelings can occur when behavior problems arise in siblings with disabilities and the typically developing sibling’s identifying features of the disability in themselves. Petalas et al. (2012)explored the interactions between genetic liability (e.g., the Broad Autism Phenotype) and environmental stressors in predicting the adjustment of siblings of individuals with autism spectrum disorder and the quality of the sibling relationships. They found that sibling adjustment was associated with the extent of behavior problems in the child with autism spectrum disorder and with the extent of the typically developing sibling’s Broad Autism Phenotype features (i.e. difficulties in language, cognition, socialization, and emotional experience). Relationships between siblings were more negative when the child with autism spectrum disorder had more behavior problems and when there was evidence of critical expressed emotion (relationship with relatively high criticism, e.g., use of highly critical evaluative phrases such as “I hate it” when speaking about their sibling’s behavior) in the family environment. Typically developing siblings with more Broad Autism Phenotype features, who had brothers/sisters with autism spectrum disorder with a greater number of behavior problems, had more behavior problems themselves. Additionally, sibling conflict was more frequent in siblings with more Broad Autism Phenotype features who had parents with mental health problems (Petalas et al. 2012).

Research in sibling relationships has shown both positive and negative impacts and outcomes for the typically developing sibling. The typically developing sibling is provided with opportunities to process situations, manage stress, take responsibility, become more resilient, and practice patience and compassion. For the sibling with disabilities, they are provided with a role model, which provides opportunities to experiment with certain behaviors and attitudes and learn vicariously from the typically developing sibling’s actions. Conversely, the typically developing sibling can experience more pressure to achieve and protect their sibling with disabilities, which can carry over into other relationships. Siblings with disabilities can negatively impact relationships if they have behavior issues that the typically developing sibling struggles to understand or that negatively impact the family dynamic.

Friends and Peers

Many young people with disabilities may either not see difference between themselves and their typically developing peers, or they may choose to look beyond their disabilities seeking normalcy. Often, adolescents with disabilities do not perceive themselves as different from their peers. However, their peers frequently perceive and treat them differently. Similar to their typically developing peers, adolescents with disabilities value the importance of friendship. Regrettably, lower levels of social skills connected with their disability lead adolescents with disabilities to struggle establishing meaningful connections with their typically developing peers, hindering the development of meaningful friendships. Middle childhood and adolescence are periods when youth become increasingly aware of individual differences, which can lead to rejection and stigmatizing of individuals with disabilities.

Paradoxically, the actual disability has little baring on how individuals with disabilities conceptualize themselves, but it is a determining factor for how others conceptualize them. Skär (2003) interviewed twelve adolescents with disabilities multiple times at the participant’s home seeking to better understand how adolescents with disabilities perceived social roles and relationships to peers and adults. Adolescent with disabilities gave a description of themselves as regular members of the adolescent group, even though they were fully cognizant of their disability. At the same time, however, the adolescents felt that others, both their typically developing peers and adults, saw them as drastically distinctive because of their disability. The relationships to friends of the same age were either markedly defective or non-existent, while relationships to adults were often characterized as ambivalent or asymmetric, conceivably as a result of these beliefs held by the adolescent with disabilities (Skär 2003). Diamond et al. (2007) illuminate another potential reason for challenges in establishing and maintaining friendships for adolescents with disabilities. They report that these youths often feel powerless and alienated, more than their typically developing peers (see also Brown et al. 2003).

Common concerns of parents and other adults regarding adolescents with disabilities is that they have fewer friends, fewer opportunities for friendships, and lower participation rates in social and recreational activities, possibly resulting in greater loneliness throughout their teenage years (Solish et al. 2010). Fewer opportunities to participate in activities contributes to lower rates of quality friendships (Orsmond et al. 2004), which can lead to less access to protective functions of friendship including confidence, self-esteem and sense of belonging. This is exacerbated in the social lives of adolescents with severe disabilities, which researchers suggest that peer interactions and durable friendships are rare or altogether absent for this population (e.g., Petrina et al. 2014; Webster and Carter 2007).

Adolescents with disabilities have friendships that are characterized by less warmth/closeness and less positive reciprocity than the friendships of their typically developing peers. Likewise, adolescents with disabilities spent less time with friends outside of school and were less likely to have a cohesive group of friends. For adolescents with disabilities, internalizing behaviors may actually prevent the social interaction needed to develop friendships (Tipton et al. 2013). As a result, youth with disabilities are often perceived as less socially competent and of lower social status than their typically developing peers, and they struggle to resolve social conflict with peers (Solish et al. 2010).

Even with the difficulties in the development of friendships highlighted above, most adolescents with disabilities report satisfying friendships. These friendships are most often developed and maintained with peers who also have disabilities, and tend to be more stable and positive than friendships with typically developing peers. Indeed, friendships in disability-typically developing dyads are less common; nevertheless, most modern typically developing students tend to have fairly tolerant attitudes towards peers with disabilities. Bossaert et al. (2011) highlight that certain qualities are more likely to enhance positive views that adolescents have of their peers with disabilities. These characteristics include being female, having a close family member or a good friend with a disability, and having frequent contact with a person with a disability (Bossaert et al. 2011).

While opportunities for shared activities, such as participation in sports and recreational activities, are less frequent for young people with disabilities than their typically developing peers, when they do occur, they contribute to friendship quality. Martin and Smith (2002) studied friendship quality among those who participate in youth disability sport using the Sport Friendship Quality Scale (Weiss and Smith 1999) with a sample of 85 males and 65 females who competed in disability sport. They found that adolescent athletes with disabilities viewed their friendships as having a positive and a negative dimension to them, with much of the negative being attributed to conflict experiences. Additionally, females reported higher levels of positive friendship acts compared to males. However, there was no difference in perceptions of the negative dimension of friendships between the genders (Martin and Smith 2002).

Matheson et al. (2007) studied friend qualities that adolescents with and without disabilities identify as the most important. They found that those with disabilities deemed different qualities important than typically developing adolescents. In fact, typically developing adolescents often identified intimacy/disclosure, support, reciprocity, conflict management, and trust/loyalty as the most important. Instead, adolescents with disabilities valued companionship, similarity, proximity, and stability (Matheson et al. 2007).

Relationships, namely friendship and peer interactions, gain in importance for all students throughout adolescence. It is particularly noteworthy for those with disabilities as they integrate at school and prepare transition to adulthood. Thus, it is important to understand descriptors, development, and processes of friendships among individuals with disabilities. Adolescents with disabilities and their friends identity five descriptors for their friendships: (a) excitement and motivation, (b) shared humor, (c) normalized supports, (d) mutual benefits, and (e) differing conceptions of friendships (Rossetti 2015). Additionally, there are five aspects that relate to the formation of positive peer relationships: (a) perceived similarity in interests and ability, (b) the role of the adolescent without disabilities in the relationship, (c) amount of time spent together, (d) peer reactions towards students with disabilities, and (e) adult behavior towards students with disabilities (Kalymon et al. 2010). Salmon (2013) studied the process of friendship development and maintenance among adolescents with disabilities—the variety of strategies utilized to make and keep friends. These include disrupting norms about friendship, the process of coming out as disabled, connecting with and developing friendships with others through stigma, and choosing self-exclusion (Salmon 2013).

Friendship creation and development can be difficult for adolescents with disabilities, particularly as they seek to understand their disability and how they assimilate with others. These difficulties are further perpetuated by a lower level—or complete lack—of involvement in recreational and extracurricular activities. Despite these difficulties, adolescents with disabilities still report positive friendships, most often with other individuals with disabilities. However, disability-typically developing dyads do exist. Even though they identify different friend qualities as most important, there are similarities between typically developing adolescents and adolescents with disabilities in friendship descriptors and friendship formation and maintenance.

School, Technology, and Extracurricular Activities

School type impacts the ability of adolescents with disabilities to succeed in various aspects of life, including feeling normal by participating in activities and developing positive relationships. Government mandates encourage the practice of inclusion, which reflects a philosophy that students with disabilities should be educated, to the maximum extent appropriate, in general education classrooms. This enhances the development of social and life skills for adolescents with disabilities both inside and outside of the classroom. Technology provides additional opportunities for adolescents to safely explore their identity and independence, while also improving their overall quality of life. Extracurricular activities provide opportunities for adolescents with disabilities to develop friendships, form an identity beyond their disability, extend their autonomy, and develop greater self-confidence.

Jamieson et al. (2009) sought to understand the nature of friendships of adolescents with disabilities when they attend inclusive high schools. Opportunities to interact with their typically developing peers at school through inclusion course allows for more opportunities for adolescents with disabilities to develop friendships and participate in activities that may not otherwise be available to them. Further, courses allows the individual with disabilities to see beyond their disability, this was aided when the individual, their friends, or others facilitate accessibility (Jamieson et al. 2009). Due to academic difficulties and underachievement, students with disabilities receive varying levels of special education services. However, inclusive education has been associated with improved academic outcomes for students with disabilities (Dessemontet et al. 2012; Kurth and Mastergeorge 2010). In fact, Westling and Fox (2009) found that students with disabilities, taught in general education classes, tended to perform better on measures of achievement, including reading and mathematics, than students taught in partial or complete pull-out programs. In order for inclusion to be successful, adaptations to meet individual student needs are necessary (Kurth and Keegan 2012). It is more challenging to suitably integrate adolescents with severe disabilities into general education courses. This is particularly true since the limited involvement of adolescents with severe disabilities in general education courses and extracurricular activities may reflect, in part, a perception that many students with severe disabilities lack the social and behavioral skills needed to participate actively in inclusive activities with their peers (Carter and Hughes 2006; Kleinert et al. 2007; Lyons et al. 2016).

Teachers’ view of their responsibility for student learning is an important factor that affects inclusion, and may differ across general and special education teachers. Jordan et al. (2009) found that teachers who take ownership for the education of students with special needs are more effective at teaching all students. Additionally, they discovered that the difference between effective and ineffective inclusion may lie in teachers’ beliefs about who has primary responsibility for students with special education needs. Teachers’ perceptions of self-efficacy regarding their ability to teach in inclusive settings appear to be similarly related. Teachers often report that lack of training contributes to their lack of self-confidence (Wilkins and Nietfeld 2004). Conversely, teachers who feel confident in their ability to include all students often identify their experiences and training in special education as a factor that contributed to this positive attribution (Lohrmann and Bambara 2006). Collaboration between teachers (particularly general and special education teachers) is an important strategy for supporting student learning in inclusive settings and ensuring that students receive appropriate support (Santoli et al. 2008).

While technology is frequently used in the classroom to enhance the educational environment (see Bargerhuff et al. 2010; Kennedy and Deshler 2010; Kennedy et al. 2013), positive outcomes also exist outside the classroom. Researchers have shown that individuals with disabilities successfully use technology to improve their quality of life, establish independence, and strengthen their identity (Muncert et al. 2011; Charnock and Standen 2013). Technology can help individuals with diverse communication disabilities to combat insufficient social participation (Shattuck et al. 2011). Social media, for example, provide opportunities for young people with communication disabilities, especially those living in rural areas, to use mainstream technology to overcome lack of proximity to build social connections and/or strengthen social networks. In order to benefit from learning to use social media in rural areas, parents and service providers need knowledge and skills to integrate assistive technology with the technology and social needs of this group (Raghavendra et al. 2015). Furthermore, technology can be utilized to teach adolescents with disabilities daily living skills and serve as a method to remind them to complete necessary daily activities, such as bathing, brushing teething, eating, and cleaning. Researchers highlight the positive effects of teaching individuals with disabilities to use various technologies to independently self-prompt their daily living tasks (Cullen and Alber-Morgan 2015). Self–prompting is presenting antecedent cues such as textual prompts, picture prompts, or video prompts in order to guide oneself accurately and efficiently through a task (Ayres and Cihak 2010; Van Laarhoven et al. 2010).

Sport participation is the most commonly studied extracurricular activity for adolescents with disabilities. Extracurricular disability sport participation provides athletes with an opportunity to interact with a best friend who provided them with a variety of important self-enhancing benefits. As mentioned previously, disability sport provides an important vehicle for promoting positive peer relations between adolescents with disabilities and both their typically developing peers and peers with disabilities (Martin and Smith 2002). Most of those with disabilities who participate in sports are committed to and enjoy their sports experience (Martin 2006). Individuals with disabilities often utilize sports as a means to improve their quality of life and form an identity (Anderson 2009; Hutzler et al. 2013).

Both special education and school type play a central role in how adolescents with disabilities are perceived and how well they succeed. Inclusive education promotes opportunities for the adolescent to participate in activities and programs that otherwise would be unavailable to them. Teachers’ attitude and beliefs about their role can greatly enhance or diminish the success of the adolescent. Technology plays an important role in academic, social, and life skill achievements. Extracurricular activities can assist in development of peer relationships and identity, but understanding the role that these activities play in the life of adolescents with disabilities outside of the sports realm is limited.

Bullying

Adolescents with disabilities are likely targets and victims of bullying, many times not realizing that it is occurring. While having a disability potentially makes them an easier mark, bullying is often the result of factors relating to the disability. These factors include attributes common to those with disabilities like lower social skills, increased problem behaviors, and a more trusting attitude. Tragically, these same behaviors, coupled with a desire for friends, frequently contribute to them becoming bullies. The impact of bullying is more emotionally difficult and damaging for those with disabilities.

Adolescents with disabilities are more likely to report that they had been bullied than students without disabilities, and the risk of being bullied increases when students reported having both a disability and a restriction in school participation (Rose et al. 2015). Using data from 12,048 adolescents, Sentenac et al. (2011) explored bullying victimization among adolescents with either a disability or a chronic illness across individual, social, and family factors. They found associations between bully victimization and weaker social support and difficulties communicating with their fathers. These associations were even stronger among students with disabilities (Sentenac et al. 2011). Additionally, many youth with disabilities experience social difficulties and relatively low levels of social competence. In fact, when compared with their typically developing classmates, students with disabilities were more likely to be disliked and to have peer acceptance problems (Chamberlain et al. 2007; Koster et al. 2010; Symes and Humphrey 2010). Although students with disabilities may be disproportionately at risk for involvement in peer victimization, the presence of a disability itself may not be the most important risk factor. Rather, factors that commonly accompany the disability, such as problems with social skills, communication difficulties, and/or internalizing and externalizing behaviors, may compromise their social status and further increase their risk for involvement as a victim or perpetrator (Bellini et al. 2007; Blake et al. 2012; Christensen et al. 2012).

Beyond the individual characteristics, bullying and victimization differ by disability. Zeedyk et al. (2014) interviewed youth, with and without disabilities, and their mothers to investigate incidences of bullying or victimization. Adolescents with autism spectrum disorder were victimized, physically and verbally, more frequently than their peers with intellectual disabilities and typically developing peers. Higher internalizing problems and conflict in friendships were found to be significant predictors of victimization. The emotional impact of bullying and victimization was higher in those with disabilities compared with their typically developing peers (Zeedyk et al. 2014).

Researchers have sought to understand the characteristics of adolescents with disabilities who are victims, bullies, or bully-victims. Students with disabilities, who experience high levels of peer victimization and are considered pure victims, have elevated rates of individual and social risk factors. These factors include depression and internalizing behavior problems, social communication and social competence difficulties. The youth also experience increased social isolation or affiliate with peers who do not support or protect them from bullying (Rose et al. 2013; Son et al. 2014; Turner et al. 2011). Youth with disabilities who are pure bullies tend to have higher levels of positive social characteristics and school bonding, and lower levels of school adjustment problems (Farmer et al. 2012). Furthermore, students with disabilities who affiliate with aggressive peers and peers who were perceived to be popular by classmates tend to be more likely identified as bullies and were less likely to be victimized as compared with other students with disabilities (Estell et al. 2009). Bully-victims perpetrate significantly more physical and verbal bullying than pure bullies, and were more frequent targets of physical, verbal, indirect, and cyber bullying than students identified as pure victims (Yang and Salmivalli 2013). This dynamic may be particularly problematic for youth with disabilities, as they struggle with developmentally appropriate social skills, and they may experience interpersonal relationship difficulties that lead to increased reactive aggression and emotion dysregulation (Rose and Espelage 2012). Difficulty making friends also appears to be a significant predictor of being a bully-victim for youth with disabilities (Zablotsky et al. 2014).

As demonstrated by current research in the field of adolescents with disabilities, they are more likely to be bullied than their typically developing peers. Much of the risk of bully victimization relates more to difficulties associate with their disability than the disability itself, including social deficits and externalizing behaviors. While they are bullied more frequently, these adolescents may also be bullies themselves. Social abilities along with their friend group, or lack thereof, contribute to the frequency of being bullied, bullying others, or a combination of bullying and being bullied.

Psychosocial Development Issues

Adolescents with disabilities often lag behind their typically developing peers psychosocially. Adolescents with disabilities desire the same developmental milestones as their typically developing peers such as establishing friendships, developing an identity, and evaluating their familial relationships. Unfortunately, they routinely lack the cognitive, emotional, and behavioral ability/autonomy to do so. The limited research on psychosocial development of adolescents with disabilities has centered primarily on self-concept, positive parent and peer relationships, and optimism and depression (Humphrey et al. 2013; Mueller and Prout 2009).

Identity

The identity development was central to Erikson’s model of human development. During adolescence, individuals seek to develop a personal identity, independent of their parents and peers, while also ensuring that they are meeting societal norms (Erikson 1963). Extensive literature, exploring identity development in typically developing youth, abounds. However, the majority of the scant research on identity development in adolescents with disabilities focuses narrowly on the progression and development of sexual identity (Wilkinson et al. 2015; Swango-Wilson 2010) or the developmental process of social identity through social construction of what these youth observe from peers and siblings (Zolkowska and Kaliszewska 2014).

As adolescents with disabilities explore their identity, they recognize that everyone is different, redefining how they perceive themselves. Lingam et al. (2013) used qualitative interviews to gain an in-depth understanding of the experiences and aspirations of a group of young people with disabilities. They found that, for these youth, identity formation is a combination of their life experiences and how they perceived their disability, including the ensuing differences and difficulties. Furthermore, the adolescents’ self-perception was specifically influenced by their perception of how friendship groups saw them in school and their perception of their family’s attitude toward them at home. Finally, a positive sense of identity and self-worth stemmed from being part of a social network that provided a sense of belonging, preferably one that valued differences as well as similarities (Lingam et al. 2013).

Attachment

Attachment relationships are of even greater importance to young people with disabilities, because of their reduced coping resources. However, forming these attachment relationships may be more difficult for individuals with disabilities because the methods of communication and behaviors they express may be more difficult for the caregiver to decipher (Clasien de Schipper et al. 2006), which in turn may decrease the caregivers’ sensitivity and responsiveness to the child. Parental factors, such as increased stress associated with caring for a child with disabilities and accepting the diagnosis of disability, may also negatively impact the development of attachment relationships (Janssen et al. 2002).

Abubakar et al. (2013) extensively explored attachment patterns in individuals with disabilities. Adolescents with disabilities may become more strongly attached to their peers who are experiencing similar conditions. As a result, adolescents with disabilities often have higher scores in peer attachment measures compared with those without disabilities. Further, youth with disabilities generally have a similar quality of attachment with both mothers and peers, but they have significantly lower attachment with fathers (Abubakar et al. 2013). It is interesting to note that research focusing on young children indicates a positive relationship between paternal involvement in the child’s caretaking and the quality of father–child attachment (Newland et al. 2008). However, during adolescence, individuals with learning disabilities report less secure attachment relationships with both mothers and fathers compared to their typically developing peers (Al-Yagon 2012). Moreover, there is growing evidence to suggest that youth with intellectual disabilities may be less likely to be classified as securely attached compared to their typically developing peers and peers with other types of disabilities (Weiss et al. 2011).

Autonomy

Autonomy is not solely a function of behaviors one can do independently, but rather of accepting responsibility, and making decisions for oneself in a context of social connectedness (Crittenden 1990). Self-determination is essentially a person’s ability to independently make meaningful life choices and encompasses activities such as problem solving, decision making, goal setting, self-observation and evaluation, self-management and reinforcement, acquiring an internal locus of control, experiencing positive attributions of efficacy and outcome expectancy, developing a realistic and positive self-image, and self-awareness (Clark et al. 2004). Obtaining a sense of autonomy constitutes a major goal for most individuals with disabilities, particularly in the transition from childhood to adolescence and adolescence to adulthood. Autonomy, for adolescents with disabilities, includes taking responsibility for their behavior, making decisions regarding their lives, and maintaining supportive social relationships (Crittenden 1990). One area where adolescents with disabilities can begin to exercise autonomy with the support and influence of family members involves making medical decisions (Racine et al. 2012). Terrone et al. (2014) studied the relationship between adolescent autonomy and their perceptions of feelings and attitudes experienced within the family in adolescents with and without disabilities. While all family members influence the level of autonomy in typically developing adolescents, mothers, once again, had a significant influence on the level of autonomy of adolescents with disabilities (Terrone et al. 2014).

Self-Esteem

There is evidence that for people with disabilities stigmatization can have a negative impact on their psychological well-being, lowering their self-esteem and negatively affecting their mood (Abraham et al. 2002; Dagnan and Waring 2004; Szivos-Bach 1993). Those who were most aware of being stigmatized had the lowest self-esteem scores (Szivos 1991). Disability has been associated with a lower sense of self-worth, greater anxiety, and less integrated view of self for some, while others have no differences in global self-esteem comparing groups of children and adolescents with and without disabilities (Shields et al. 2007).

Studies that involve people with disabilities have shown that negative social comparisons are related to lower self-esteem scores and higher levels of depression. Dagnan and Sandhu (1999) investigated the relationship between social comparison, depression and self-esteem in individuals with disabilities. They found that total social comparison scores positively associated with total self-esteem scores and negatively associated with reported levels of depression (Dagnan and Sandhu 1999). Literature beyond the Dagnan and Sandhu study focused on self-esteem for those with physical disabilities (see Jemtå et al. 2009; Manuel et al. 2003; Miyahara and Piek 2006).

Research into aspects of psychosocial development of adolescents with disabilities is markedly limited in comparison to other areas that are important to their growth. However, there have been some key findings that can be built upon to further develop research in the area. Being a part of a social network, along with friend and family perceptions, play an important role in identity development. Adolescents with disabilities tend to have high attachment levels to both peers and parents, particularly mothers. However, these attachments are often not secure. During the transition from childhood to adolescence and then from adolescence to adulthood, the need for autonomy increases. Families of adolescents with disabilities need to encourage, support, and assist in activities that encourage safe and secure autonomy development. Stigmatization can be a key contributor to low self-esteem in adolescents with disabilities, especially during this developmental period when they become more aware of the perceptions of others and comparison is increased.

Discussion

Adolescents with disabilities have similar desires and face many of the challenges common to their typical developing peers. However, the ways that they navigate this developmental stage differs from their typically developing peers. Relationships, both within and outside the family, play a role in the overall development of the adolescent with disabilities.

Family relationships are bi-directional in nature and play an important role in the success of the individual. While parents often experience stress as they seek to better understand and communicate with their child, intervention and educational programs can help them navigate the adolescent period. Siblings experience both positive and negative outcomes from having a brother or sister with a disability. This family dynamic can help them to be more responsible, resilient, and compassionate. On the other hand, aspects of the disability can lead to embarrassment and struggle for the typically developing sibling. While they have limitations in friendship development, due to accessibility and sociability, most adolescents with disabilities develop healthy relationships—most commonly in disability dyads. Adolescents with disabilities describe their friends in ways that are similar to their typically developing peers. However, this population is more likely to be victims of bullying due to difficulties associated with the disability, such as social deficits and problem behaviors. School type and teachers’ attitudes and beliefs about educating adolescents with disabilities play a central role in academic success of adolescents with disabilities. Technology and extracurricular activities can contribute to the development of life skills, and assist in relationships and identity formation.

The shortage of literature on psychosocial development of adolescents with disabilities is alarming, because of its importance for this populations’ transition to adulthood. Social groups, peers, and parents are keys to the development of identity, attachment, and autonomy. During the adolescent development stage, where comparisons increase and they become more aware of their differences, this population may be at greater risk for lower self-esteem. While there are difficulties and challenges during this stage, it is possible for the adolescent with disabilities to successfully traverse this developmental period, when supports and key relationships are in place.

This narrative review of developmental issues relating to adolescents with disabilities provides evidence that the current state of our knowledge base for this group of adolescents is lacking. Indeed, there has been little done to methodically investigate this important stage of development for youth with disabilities, resulting in a disabling the adolescent disability literature. The need for systematic and comprehensive investigations into these developmental issues is imperative, from a policy perspective, given the current emphasis on inclusion for the development of social skills and networks for children and adolescents with disabilities and the push for educational and vocational opportunities for adults with disabilities. The work that has been done is laudable, but there is still a great deal left to accomplish. A good first step in embarking on a systematic approach to research in this field would require consideration of four key points that emerged from the literature review. Salient issues include increasing the number of studies that focus specifically on adolescence across the various types of disabilities, establishing a theoretical base to anchor research, forming cohesion across disabilities among researchers, and taking a comprehensive approach to intervention studies. By addressing these issues in future research in this field, scholarly knowledge will be increased, but more importantly, the lives of young people with disabilities will be greatly enhanced.

This review of literature made it clear that studying the developmental implications of disabilities decrease as individuals age. The richness, both in quality and quantity, of the disability literature for childhood (not included in this review), is encouraging. However, there is insufficient research into most developmental aspects of adolescence. This is most alarming because the developmental transitions of adolescence are paramount to the important milestone for persons with disabilities of transitioning to adulthood. We need extensive and systematic inquiry of adolescents in both depth and breath, especially as it relates to overcoming disability related barriers. A better understanding of developmental aspects and relationships for adolescents with disabilities would provide understanding to the individual, families, providers, and others who interact with and support this population.

Currently, the research in adolescents with disabilities also lacks uniform theoretical grounding. Most studies avoid explicitly invoking a theoretical stance, reducing both the scholarly utility and the collaborative value of the research. Going forward, human development theories can be applied to enhance and guide the inquiry within this population. Social Cognitive Theory (Bandura 1977, 1986) is one example of how we could provide a theoretical foundation to understand how adolescents with disabilities develop, as well as cultivate and preserve relationships. Through this lens, researchers could examine how observational learning occurs in adolescents with disabilities as they seek to understand appropriate behaviors and comprehend changes that are occurring. Additionally, researchers can develop an understanding of the types of appraisals that are used in self-efficacy. Finally, exploring triadic reciprocal determinism (observed behavior, cognition and other personal factors, and environmental factors) would allow for deeper understanding of what is the most salient aspect of adolescent development in disabilities, regardless of the type of disability. Erikson’s Theory of Psychosocial Development (Erikson 1950, 1963, 1968) is another example of how scholars can utilize a theoretical framework to understand the developmental processes of adolescents with disabilities. Through this lens, researchers could seek to better understand differences between adolescents with disabilities and their typically developing peers in terms of how they navigate the crises of each developmental stage. Several other theories could also be appropriately applied. The idea is to anchor our research theoretically so, as we progress in our knowledge base, common ground exists for interdisciplinary collaboration.

Researchers in the area of adolescents with disabilities need to work together to develop a common core of disabilities. The adolescents with disabilities literature is often disability specific and research applicability and generalizability across disabilities is scarce. Obviously, there is some advantage to provide disability specific knowledge. However, from a wide-lens perspective, those positives are outweighed by the inability to apply the findings from one study to another across disabilities. As was demonstrated in the review, research across multiple types of disabilities is meager and not up to date. Individuals with disabilities vary depending on the type and level of disability; even those with similar diagnoses can frequently differ in behaviors, needs, and attitudes. Nonetheless, examining disabilities as a whole would be most useful, especially to those who work with a variety of disabilities. Most intervention programs, special education programs, and extracurricular activity programs work with a heterogeneous group of young people with disabilities. A systematic understanding of how to support and encourage positive development and interactions in adolescents with disabilities could promote greater support for this population.

A comprehensive assessment of adolescent development and disabilities would also provide greater understanding of the impact of various disabilities on development and interactions and increase the worthwhileness of intervention opportunities. These interventions could include the individual, their family members, teachers/staff, and/or other professionals—taking a team approach to make the individual with disabilities’ life more meaningful while promoting independent choices. These interventions are needed to help the adolescent with disabilities successfully traverse the adolescent developmental period and prepare for adulthood. Families are empowered when interventionists involve parents and facilitate their understanding of available family resources and services for their child with disabilities. Additionally, relevant interventions for the adolescent with disabilities can help them feel more involved, enabling them to take an active role in decisions about their lives. One way to do this might be to provide the adolescent with disabilities the necessary social training to interact in a variety of settings and augment their understanding of the skills necessary to build and maintain healthy relationships, no matter the type or level of disability. When researchers in the area of disabilities work together and develop a common core of disabilities, research studies in the adolescents with disabilities literature will increase in utility. Additionally, meeting the greater need for collaboration and understanding of the impact of disabilities will promote applicability and usefulness for providers, parents, interventionists, educators, and others.

Conclusion

Adolescents with disabilities face many of the same challenges as their typically developing peers. However, the ways they resolve them may differ. Additionally, the type and level of disability may impact the subsequent adjustment and integration. While the current research of adolescents with disabilities has helped to promote initial understanding of challenges for this population, there are still significant issues that need to be addressed to fully understand the developmental trajectories of these youth and to truly have an impact on the lives of those with disabilities. This includes a need for better understanding the developmental patterns unique to adolescents with disabilities in relation to relationships (familial and friendships), school and extracurricular activities, and overall psychosocial development. As we extensively and systematically expand our knowledge we can enable, instead of disable, the adolescents with disabilities literature. This will promote greater acceptance of all individuals and increase quality of life for all involved.

References

Abraham, C., Gregory, N., Wolf, L., & Pemberton, R. (2002). Self-esteem, stigma and community participation amongst people with learning difficulties living in the community. Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology, 12, 430–443.

Abubakar, A., Alonso-Arbiol, I., Vijver, F., Murugami, M., Mazrui, L., & Arasa, J. (2013). Attachment and psychological well-being among adolescents with and without disabilities in Kenya: The mediating role of identity formation. Journal of Adolescence, 36, 849–857.

Aggies Elevated. (2015). Retrieved from http://www.aggieselevated.com/

Al-Kandari, H. Y. (2015). High school students’ contact with and attitudes towards persons with intellectual and developmental disabilities in Kuwait. Australian Social Work, 68(1), 65–83. doi:10.1080/0312407x.2014.946429.

Al-Yagon, M. (2012). Adolescents with learning disabilities: Socioemotional and behavioral functioning and attachment relationships with fathers, mothers, and teachers. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 41(10), 1294–1311. doi:10.1007/s10964-012-9767-6.

Anderson, D. (2009). Adolescent girls’ involvement in disability sport: Implications for identity development. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 33(4), 427–449.

Asher, S. R., & Paquette, J. A. (2003). Loneliness and peer relations in childhood. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 12, 75–78.

Ayres, K., & Cihak, D. (2010). Computer- and video-based instruction of food-preparation skills: Ac-quisition, generalization, and maintenance. Intel-lectual and Developmental Disabilities, 48, 195–208.

Azeem, M., Dogar, I., Shah, S., Cheema, M., Asmat, A., Akbar, M., et al. (2013). Anxiety and depression among parents of children with intellectual disability in Pakistan. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 22(4), 290–295.

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Bargerhuff, M. E., Cowan, H., & Kirch, S. A. (2010). Working toward equitable opportunities for science students with disabilities: Using professional development and technology. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology, 5(2), 125–135. doi:10.3109/17483100903387531.

Begum, G., & Blacher, J. (2011). The sibling relationship of adolescents with and without intellectual disabilities. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 32, 1580–1588.

Bellini, S., Peters, J. K., Benner, L., & Hopf, L. (2007). A meta-analysis of school-based social skills interventions for children with autism spectrum disorders. Remedial and Special Education, 28, 153–162.

Betz, C., Nehring, W., & Lobo, M. (2015). Transition needs of parents of adolescents and emerging adults with special health care needs and disabilities. Journal of Family Nursing, 21(3), 362–412.

Beyer, J. F. (2009). Autism spectrum disorders and sibling relationships: Research and strategies. Education and Training in Developmental Disabilities, 44, 444–452.

Billingsley, B., McLeskey, J., & Crockett, J. B. (2014). Principal leadership: Moving toward inclusive and high-achieving schools for students with disabilities (Document No. IC-8). Retrieved from University of Florida, Collaboration for Effective Educator, Development, Accountability, and Reform Center website: http://ceedar.education.ufl.edu/tools/innovation-configurations/

Blake, J. J., Lund, E. M., Zhou, Q., Kwok, O., & Benz, M. R. (2012). National prevalence rates of bullying victimization among students with disabilities in the United States. School Psychology Quarterly, 27, 210–222.

Bossaert, G., Colpin, H., Pijl, S. J., & Petry, K. (2011). The attitudes of Belgian adolescents towards peers with disabilities. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 32(2), 504–509.

Boyle, C., Boulet, S., Schieve, L., Cohen, R., Blumberg, S., Yeargin-Allsopp, M., et al. (2011). Trends in the prevalence of developmental disabilities in US children, 1997–2008. Pediatrics, 127(6), 1034–1042.

Brown, M. R., Higgins, K., Pierce, T., Hong, E., & Thoma, C. (2003). Secondary students’ perceptions of school life with regard to alienation: The effects of disability, gender, and race. Learning Disability Quarterly, 26, 227–238.

Caplan, R. (2011). Someone else can use this time more than me: Working with college students with impaired siblings. Journal of College Student Psychotherapy, 25, 120–131.

Carter, E. W., & Hughes, C. (2006). Including high school students with severe disabilities in general education classes: Perspectives of general and special educators, paraprofessionals, and administrators. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 31, 174–185. doi:10.1177/154079690603100209.

Chamberlain, B., Kasari, C., & Rotheram-Fuller, E. (2007). Involvement or isolation? The social networks of children with autism in regular classrooms. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37, 230–242. doi:10.1007/s10803-006-0164-4.

Charnock, D., & Standen, P. J. (2013). Second hand masculinity: Do boys with intellectual disabilities use computer games as part of gender practice? International Journal of Game-Based Learning, 3(3), 43–53.

Christensen, L. L., Fraynt, R. J., Neece, C. L., & Baker, B. L. (2012). Bullying adolescents with intellectual disability. Journal of Mental Health Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 5, 49–65.

Clark, E., Olympia, D., Jensen, J., Heathfield, L., & Jenson, W. (2004). Striving for autonomy in a contingency-governed world: Another challenge for individuals with developmental disabilities. Psychology in the Schools, 41(1), 143–153.

Clasien de Schipper, J., Stolk, J., & Schuengel, C. (2006). Professional caretakers as attachment figures in day care centers for children with intellectual disability and behavior problems. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 27, 203–216.

Crittenden, P. (1990). Toward a concept of autonomy in adolescents with a disability. Children’s Health Care, 19(3), 162–168.

Cullen, J. M., & Alber-Morgan, S. R. (2015). Technology mediated self-prompting of daily living skills for adolescents and adults with disabilities: A review of the literature. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 50(1), 43–55.

Cuskelly, M. (2016). Contributors to adult sibling relationships and intention to care of siblings of individuals with down syndrome. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 121(3), 204–218. doi:10.1352/1944-7558-121.3.204.

Dagnan, D., & Sandhu, S. (1999). Social comparison, self-esteem and depression in people with intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 43(5), 372–379.

Dagnan, D., & Waring, M. (2004). Linking stigma to psychological distress: Testing a social–cognitive model of the experience of people with intellectual disabilities. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 11, 247–254.

Dessemontet, R. S., Bless, G., & Morin, D. (2012). Effects of inclusion on the academic achievement and adaptive behav-iour of children with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 56, 579–587.

Diamond, K. E., Huang, H., & Steed, E. A. (2007). The development of social competence in children with disabilities. In P. K. Smith & C. H. Hart (Eds.), The Wiley-Blackwell handbook of childhood social development (2nd ed., pp. 627–645). West Sussex: Wiley.

Doody, M., Hastings, R., O’Neill, S., & Grey, I. (2010). Sibling relationships in adults who have siblings with or without intellectual disabilities. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 31, 224–231.

Ekas, N. V., & Whitman, T. L. (2010). Autism symptom topography and maternal socioemotional functioning. American Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 115, 234–249.

Erikson, E. H. (1950). Childhood and society. New York: Norton.

Erikson, E. H. (Ed.). (1963). Youth: Change and challenge. New York: Basic Books.

Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. New York: Norton.

Estell, D. B., Farmer, T. W., Irvin, M. J., Crowther, A., Akos, P., & Boudah, D. J. (2009). Students with exceptionalities and the peer group context of bullying and victimization in late elementary school. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 18, 136–150.

Farmer, T. W., Petrin, R. A., Brooks, D. S., Hamm, J. V., Lambert, K., & Gravelle, M. (2012). Bullying involvement and the school adjustment of rural students with and without disabilities. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 20, 19–36. doi:10.1177/1063426610392039.

Ferraioli, S., & Harris, S. (2010). The impact of autism on siblings. Social Work in Mental Health, 8, 41–53.

Floyd, F., Purcell, S., Richardson, S., & Kupersmidt, J. (2009). Sibling relationship quality and social functioning of children and adolescents with intellectual disability. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 114(2), 110–127.

Graff, C., Mandleco, B., Dyches, T., Coverston, C., Roper, S., & Freeborn, D. (2012). Perspectives of adolescent siblings of children with down syndrome who have multiple health problems. Journal of Family Nursing, 18(2), 175–199.

Hartley, S., & Schultz, H. (2015). Support needs of fathers and mothers of children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45, 1636–1648.