Abstract

We study the criminal histories of 14,608 males and females in a full Stockholm birth cohort born in 1953 to age 64. Using an update of The Stockholm Birth Cohort Study data, we explore the amount of crimes recorded in the cohort before and after the advent of adulthood. We break down the age/crime curve into separate parameters, including onset, duration, and termination. Throughout, we utilize the large number of females (49%; n = 7 161) in the cohort, and compare long-term patterns of male and female criminal careers. Next, we focus on adulthood, and explore the existence and parameters of the adult-onset offender and its contribution to the overall volume of crime in the cohort. While crime peaks in adolescence, the main bulk of crimes in the cohort occurred after the dawning of adulthood. Nearly half of all male, and more than two-thirds of all female, crimes in the cohort occurred after age 25. In the case of violence, the majority of offences — around two-thirds for both genders — took place in adulthood. Around 23% of all males and 38% of all females with a criminal record in the cohort were first recorded for a criminal offence in adulthood. While a majority were convicted only once, a proportion of adult-onset offenders had a considerable risk of recidivism and repeated recidivism. These results suggest that quite a substantial proportion of the population initiate crime in adulthood, and that these offenders account for a nonnegligible proportion of adult crime.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Longitudinal criminological research rose to fame during the 1980s and 1990s following a set of influential criminal career studies (e.g., Blumstein et al., 1986; Farrington, 1986; Moffitt, 1993; Sampson & Laub, 1993). Since then, numerous developmental and life-course studies have deepened our knowledge of the complex relationship between age and crime (for recent overviews, Britt, 2019; Le Blanc, 2020). By now, it is well known that the aggregate age/crime curve conceals substantial complexity at the individual level, and may be broken down into multiple individual trajectories where some are characterized by an early onset and a subsequent frequent trajectory, while most offenders have more of a short burst of crime that begins and ends in adolescence (see Jolliffe et al., 2017; Piquero, 2008). Still others have a relatively stretched out but low-frequent trajectory, and some studies have also suggested the existence of a group which is defined by a relatively late onset of crime, often termed adult-onset offenders (e.g., Andersson et al., 2012).

To be sure, childhood and adolescence are key life-course stages for the development of criminal behavior. Whether one is a proponent of the universality of the age/crime curve (e.g., Gottfredson & Hirschi, 1990) or not (Blumstein et al., 1986), crime can be considered a youth phenomenon in the sense that participation and offending frequency typically peak in the teenage years (Cullen, 2011; Farrington, 2003). Still, developmental and life-course criminology has shown that crime does not end by the transition to adulthood and, moreover, crime in adulthood cannot merely be reduced to a matter of distant risk factors (e.g., Laub & Sampson, 2003). More generally, the life-course paradigm stresses the importance of studying the full arc of life, since not only adolescents but also adults experience fundamental biological, psychological, and social changes that are developmentally meaningful (Elder et al., 2003).

Within criminology, however, the themes of continuity and change in crime have mainly been studied up until the stage of adulthood, with a strong focus on the years of adolescence and early adulthood (e.g., Jolliffe et al., 2017). Prospective longitudinal studies with longer follow-up periods do exist, e.g., in the UK (Farrington et al., 2021), the USA (Laub & Sampson, 2003), New Zealand (Beckley et al., 2016), Canada (LeBlanc, 2020), and in Scandinavia (Bergman & Andershed, 2009; Sivertsson & Carlsson, 2015). However, many of these have been based on strata of the general population with an increased risk for delinquency, e.g., male juvenile delinquents. In order to account for continuity and change in crime across the life course, including adult-onset offending, one would need large population-representative samples of both males and females and follow them over a period covering most of their lives (Beckley et al., 2016; Moffitt, 2018). Such studies are very rare.

The Stockholm Birth Cohort Study (SBC), formerly known as the Metropolitan study, has been valuable for scholars in order to describe and analyze patterns and explanations of criminal careers up to the beginning phases of adulthood (e.g., Andersson, 1990; Andersson F., 2013; Estrada & Nilsson, 2012; Kratzer & Hodgins, 1999; Nilsson et al., 2014; Wikström, 1990). Like the majority of criminal career research, these studies were hampered by only being able to follow the criminal careers of this cohort up to age 30. Recently, however, the SBC was updated with new register data including, among other things, information on convictions, marital status, occupation, income, and health histories, following the cohort to age 64 (Almqvist et al., 2019). The updated SBC thus makes it possible to explore criminal careers to retirement age in a large, population-representative cohort of individuals, making it a unique dataset in not only Sweden, but internationally.

The Current Study

This study builds on existing work on criminal careers and traces the criminal histories of 14,608 males and females in a full Stockholm birth cohort born in 1953 to age 64. Our approach is descriptive and exploratory, with the overarching aim of providing an update on one of the few population-representative longitudinal datasets that are able to trace crime from childhood to retirement age. In that sense, our study adds to the empirical knowledge base that much developmental and life-course criminology is built upon, and, particularly, to crime in adulthood and to the phenomenon of adult-onset offending.

We begin by exploring the male and female cohort members’ cumulative life-time risk of having a criminal record to age 64, and the amount of recorded crimes committed by the cohort in adulthood. Next, we present the aggregate age/crime participation curve for the cohort to age 64, followed by a breakdown into a set of criminal career parameters, including onset, duration, and termination. We also study the association between age of onset and career duration and crime frequency, respectively. Having done so, we turn our attention to the stage of adulthood, specifically, where we explore the existence and parameters of adult-onset offenders, their contribution to the overall volume of crime in the cohort, and their risk of recidivism and repeated recidivism. Throughout, we utilize the large number of females (49%; n = 7 161) in the cohort, and compare and contrast long-term patterns of male and female criminal careers.

The Long View of Crime and Criminal Careers

The criminal career paradigm introduced a set of basic concepts making it possible to measure and describe the longitudinal sequence of crimes committed by an individual offender (Blumstein et al., 1986). Since then, the longitudinal study of crime has generated a number of key empirical observations, including (1) the crime distribution is heavily skewed with a small number of offenders committing a large number of offences at the tail end of the distribution, (2) the peak age of offending tends to occur during middle to late adolescence, (3) following adolescence is a steady decline in crime participation, (4) there is a strong degree of continuity in crime over the life span, and (5) an early onset of crime predicts a longer criminal career characterized by higher offending frequency (DeLisi & Piquero, 2011; Farrington, 2003). Influential theories within developmental and life-course criminology are built on the robustness of these patterns in predominantly male samples (see Farrington, 2005).

As longitudinal studies have become updated, providing longer follow-up lengths, criminal career researchers’ attention to crime in adulthood has increased. In this context, the importance of adulthood has mainly been reflected in the increasing number of desistance studies (e.g., Laub & Sampson, 2003), and to some extent by studies that quantify and theorize the phenomenon of adult-onset offending (e.g., Eggleston & Laub, 2002). Also, the few longitudinal studies that follow population-representative cohorts over the life-span have provided estimates for the life-time risk of a criminal record. In the most recent follow-up of the CSDD, Farrington et al. (2021) found that 44% of the London boys had been convicted of at least one crime by age 61. In the Dunedin study, a population-representative cohort of males and females born in the early 1970s in New Zealand, Beckley et al. (2016) showed that 42.2% of males and 14.8% of females were convicted at age 38. In Sweden, too, a register-based study on cohorts born during the early 1960s showed that the cumulative prevalence for a criminal conviction by age 50 was 42.4% among males and 12% among females (Sivertsson, 2018). In other words, despite quite different contexts, seen across the larger arc of the life course, being officially recorded for a criminal offence is not a rare event, at least not among males.

In the following section, we focus specifically on the theoretical and empirical controversies surrounding adult-onset offending. Given our aim to also contribute to the empirical knowledge base on gender and criminal careers, we also lend particular focus to prior longitudinal studies that have systematically explored and contrasted male and female criminal careers over some portion of adulthood.

Adult-Onset Offending

Adolescence concerns a relatively short period of life. In contrast, adulthood, by any chronological definition, covers a much longer phase of the life course. Despite the well-established age/crime curve, crime is thus not merely a youth phenomenon, since quite a substantial proportion of the total volume of crime in a given cohort may be expected to occur in adulthood (Eggleston & Laub, 2002). It is also well known that some proportion of offenders experience their first conviction as adults (Beckley et al., 2016; Eggleston & Laub, 2002). How to explain these events, however, remains a debated topic. According to Moffitt’s (1993) famous taxonomy, adult offending fits into either the small percentage of life-course persistent offenders (LCPs), or the normative adolescence-limited offenders (ALs). In other words, for Moffitt, a proportion of the adult-onset offenders are actually LCPs who were able to go undetected by the criminal justice system, and the rest are ALs who ended up being convicted in adulthood due to various social circumstances. Since the maturity gap is the main explanation for the ALs committing crime, the adult conviction should, if anything, mark the end of their career and the beginning of adulthood. According to the taxonomy, there is no need for an additional analytical category to explain crime in adulthood (Moffitt, 2008). Instead, all crime in adulthood could be traced to persistent traits established early in life, and/or normative youth delinquency which may have been prolonged a few years for a smaller proportion of the AL group, for whom the maturity gap has not yet closed.

In contrast, from a life-course view, individuals carry individual propensities and/or social disadvantages which are important dynamic variables in explaining persistence (Sampson & Laub, 1993, 1997), and desistance (Laub & Sampson, 2003). Importantly, this suggests that individuals convicted in adulthood may not merely be explained by individual-level traits and/or social disadvantages in childhood, but also be understood as a result of proximate events and/or social circumstances preceding the conviction. For example, in a British cohort study, Sapouna (2017) found that adult-onset offenders tended to have experienced negative events in adulthood, such as mental illness and drug use. On a higher abstraction level, then, the controversy concerns whether criminal events in adulthood can be traced to the belonging of certain groups (such as the LCP or AL) or whether they should primarily be explained by the near context in which they are committed.

Some have argued that adult-onset offenders account for a more significant proportion of crimes than many seem to have anticipated (Andersson et al., 2012; Eggleston & Laub, 2002; Sivertsson, 2018). Others have replied that such studies tend to overestimate adult-onset offending (Moffitt, 2006; Sohoni et al., 2014). A reason for this is often the limitation of official crime data. Generally, studies using self-reported questionnaires suggests that crime is much more prevalent than it appears to be in official records. For example, a study by Farrington et al. (2014) compared conviction data and self-reported criminal offending in the Cambridge Study of Delinquent Development (CSDD) to age 48 and found clear discrepancies between the two; compared to conviction measures, the mean number of crimes was over 30 times greater, the age of onset was earlier and the career duration longer in the self-report data. The few studies that utilized both self-reported and official data to examine adult-onset offending found that a substantial proportion of those who were arrested and convicted for the first time in adulthood had engaged in some level of undetected delinquency in their juvenile years (Beckley et al., 2016; McGee & Farrington, 2010; Sohoni et al., 2014).

At the same time, it is not clear to what extent a first criminal record in adulthood captures the continuity of undetected antisocial tendencies. After all, some degree of delinquency is so common in adolescence that it is to be considered normative rather than deviant, and even individuals who are never recorded for criminal offending tend to have self-reported delinquency in adolescence (e.g., McGee & Farrington, 2010; Moffitt et al., 1996). More restrictive definitions of juvenile offending have therefore been used to measure true adult onset. For example, McGee and Farrington (2010) argued that two-thirds of the males in the CSDD, who were first-time convicted for criminal offending at age 21 or later, were indeed true adult-onset offenders despite having self-reported criminal offending prior to age 21. These males’ offending, the authors noted, was not sufficiently serious or frequent to lead to a conviction in practice. Other, more restrictive measures for juvenile delinquency have also been used. For example, Kratzer and Hodgins (1999) utilized records on delinquency and antisocial behavior filed by the Child Welfare Committees and collected from unofficial sources such as schools, parents, neighbors, and shopkeepers. They found that 19% of the males and 24% of the females who were first recorded for a crime between age 18 and 30 (which they termed adult-starters) had unofficial records of delinquency recorded by the Child Welfare Agency between ages 13 and 18.

The controversy of adult-onset offending may also, in part, be traced to the operationalization of adulthood (Krohn et al., 2013). A main bulk of studies have defined adult-onset as being first-time arrested or convicted at age 18 or later since, in many jurisdictions, this is the age at which individuals are seen as adults in legal terms (e.g., DeLisi et al., 2018; Eggleston & Laub, 2002; Gomez-Smith & Piquero, 2005). There are, however, a number of reasons for why this cut-off point may need to be revised, at least from a developmental viewpoint. In modern, Western societies, the phase of adolescence tends to be prolonged (Moffitt, 2006), prompting Arnett (2000) to develop the notion of emerging adulthood to cover the often transitional stage of ages 18 to 25. According to Arnett (2000), this is an age phase where individuals are loosely attached to the markers of adulthood, such as stable relationships, jobs, and living arrangements, and in which they feel neither like juveniles nor adults, but a little bit of both. Recent work on brain maturation and development of the frontal lobes, which are central in controlling executive functions (such as the ability to exercise self-control), also suggests that such functions are not fully developed until the early- to mid-20 s (e.g., Belsky et al., 2020). Therefore, a more adequate definition of the adult-onset offender, particularly for younger cohorts, is being first-time arrested or convicted at age 25 or later, in the phase Arnett and others (Beckley et al., 2016) term social adulthood.

In a recent follow-up of the Dunedin study, Beckley et al. (2016) used a combination of self-report data and conviction data to analyze the criminal careers of adult-onset offenders to age 40. Based on Arnett’s (2000) age typology, they defined social adult-onset as those who were convicted at age 25 or later. Only 4% all males and 3% of all females in the Dunedin cohort met this criterion for social adult-onset. The adult-onset males represented one-tenth of all convicted males and were on average convicted two times over their lives, whereas the adult-onset females represented one-fifth of all convicted females and were on average convicted three times. Beckley et al. continued to analyze the adult-onset males on self-reported delinquency and found that a majority of them had displayed antisocial behavior and delinquency during their juvenile years (see also Sohoni et al., 2014). However, the authors also stated, statistical power was too low to analyze the adult-onset females, and for the same reason they had to include every male with a conviction at age 20 or later in the male adult-onset analyses. Overall, Beckley et al. (2016) questioned the need for a tailored theory, but also raised a continued need to study female adult-onset careers in larger population-based samples.

Gender and Crime in Adulthood

Moffitt explicitly contends that her taxonomy for explaining continuity and change in crime is gender-neutral (Moffitt et al., 2001). The taxonomy has therefore been a natural reference in studies that take on gender similarities and differences in longitudinal crime patterns (e.g., Andersson et al., 2012; Kratzer & Hodgins, 1999; Mazerolle et al., 2000). In short, the taxonomy predicts that the explanatory variables for criminal offending are similar in males and females; males are overrepresented in crime and chronic offending because they have a higher accumulation of risk factors (Moffitt et al., 2001). This aligns with the fact that males are heavily overrepresented in most crime types that are measured in official registers (Farrington, 2003). Criminal career patterns also exhibit many gender similarities, which essentially lend support to the gender-neutral position of the taxonomy (see Schwartz & Steffensmeier, 2017). For example, there is a clear association between age of onset and persistence, and females with an early onset of crime tend to have a similar versatility to that among early-onset males (Mazerolle et al., 2000). Moreover, chronic offending trajectories tend to be dominated by, or more prevalent in males than in females (Andersson et al., 2012; Block et al., 2010).

At the same time, there are a number of challenges to the gender-neutral feature of the taxonomy. These challenges are predominantly tied to age and to crime in adulthood. For one thing, the relatively few cohort studies that have systematically compared criminal career parameters across gender suggest that male overrepresentation is mainly a matter of crime participation during adolescence, and that the gender differences in both participation and frequency in adulthood are much smaller (Bergman & Andershed, 2009; Block et al., 2010; Wikström, 1990). An early observation of this pattern was made by Wikström (1990), in a detailed exposition of criminal careers in the Metropolitan cohort from ages 13 to 25. Wikström found that participation and frequency were generally much higher for males than for females, with 31% of all males in the cohort having participated in crime compared to merely 6% of the females; the frequency was 9.1 for males and 4.5 for the females. However, this was age-contingent; while differences were large during the teenage years, they were practically non-existent in crimes per offender rates during the early 20 s (p. 72).

Following Moffitt, females should have an earlier onset of delinquent behavior compared to males since they enter puberty earlier, where an earlier onset of puberty is tied to an earlier onset of delinquency through the frustration caused by the maturity gap (Moffitt et al., 2001). In contrast, the large bulk of criminal career studies which takes on gender differences and similarities indicates that females have a later onset in registered crime than do males (Andersson et al., 2012; Block et al., 2010; Mazerolle et al., 2000; Sivertsson, 2018). For example, Block et al. (2010) made a thorough exploration of criminal career parameters in the Dutch Criminal Career and Life-Course Study, where a sample of males and females could be traced over a substantial portion of adulthood. They found that while male participation peaked in adolescence, the female participation curve was much more stretched out, with a peak in early adulthood. Moreover, considerably more women had a first recorded crime in adulthood. Similarly, in a more recent follow-up of the Metropolitan cohort that employed the influential group-based trajectory method to contrast individual offending trajectories to age 30, Andersson et al. (2012) found that there was an adult-onset trajectory in females that was not found in males. Such gender differences, Block et al. (2010) stated, challenge widely accepted conclusions of developmental and life-course criminology and also require us to rethink life-span patterns in and out of crime for women (p. 93).

Data and Methods

The current study is based on the most recent follow-up of the Stockholm Birth Cohort study (Almquist et al., 2019), formerly known as the Metropolitan study (Janson, 1975).

The original study included all individuals who were born in 1953 and lived in the greater metropolitan area of Stockholm in 1963, a total of 15,117 individuals. In 2004, The Stockholm Birth Cohort Study was created by matching the anonymized Project Metropolitan to a temporary research database called the Work and Mortality Database (WMD), generating a sample of 14,294 of the original cohort members (Stenberg & Vågerö, 2006). This made it possible to prospectively study crime in the cohort to age 30 and welfare outcomes such as education, occupation, and income up to age 53 (e.g., Estrada & Nilsson, 2012; Nilsson et al., 2014).

The current study utilizes the second follow-up of the original Metropolitan cohort, conducted as part of Reproduction of Inequality Through Linked Lives (RELINK). In order to collect and merge new administrative data, a new matching procedure was employed in 2018/2019, from which 14,608 individuals of the original metropolitan cohort were identified (Almqvist et al., 2019). This constitutes the study population for the current paper. The people whose criminal careers we trace here were thus born in Stockholm in 1953, grew up in the 1960s, and entered adulthood in the late 1970s. We will return to these contextual elements of the study in relation to the notion of adult-onset offending, and to gender differences and similarities in criminal careers, later in the paper.

Data and Measures

We use three data sources to measure criminal offending: Child Welfare Committee (CWC) data covering ages 9 to 19, individual crime level (INCRI) data as measured in the National Police register between ages 13 and 29, and crime conviction data from age 20 through to 64. The triangulation of these data sources has two particular advantages for the purpose of our study. First, the measures originate from different registers and authorities but overlap during certain age periods. This enables a validation of the measurement of the age/crime relationship. Second, both CWC and INCRI cover indicators for deviance and crime before the minimum age of criminal responsibility in Sweden (i.e., age 15). In the case of adult-onset offending, this feature of our study design makes it less likely that individuals with a high propensity for deviance and criminal behavior, whatever the causes for this behavior may be, are able to remain undetected.

CWC Data

The origins of the CWC data can be found in the so-called Social Register, which collects data from municipalities and other (national) agencies covering a breadth of welfare problems relating to the cohort members and their families (for a description of the register and the collection of CWC data, see Project Metropolitan, 2005a and 2005b, Codebook II and Codebook IV). At the time of data collection, each Swedish municipality had to record its decisions and interventions regarding social welfare cases (Janson, 1980). Data were coded according to a detailed manual to minimize subjective factors. In essence, the part of the CWC data that we utilize comprise “criminal acts and other forms of deviant behaviors being the causes of the CWC’s actions during each year” (Project Metropolitan, 2005b, Codebook IV, p. 10). These records were coded yearly between 1962 and 1972, thus covering ages 9 to 19. Since the police were allowed to file records for offences committed by offenders below the age of 15 only in extremely serious cases (Project Metropolitan, 2005b, Codebook IV, p. 34), CWC data is a more accurate measure than police data when covering the cohort’s offending prior to age 15.

In contrast to the police records, CWC data also contains information on criminal and antisocial behavior from unofficial sources such as schools, parents, neighbors, and shopkeepers (Project Metropolitan, 2005b, Codebook IV, p. 34). It should, however, be noted that CWC only covers information on cohort members living in the city of Stockholm, and that the data does not measure the number of criminal acts, but instead the number of actions taken by the CWC. The frequency measures are therefore not comparable to criminal justice data. We separate between behavior that was clearly considered lawbreaking at the time (e.g., typical youth crime such as theft and vandalism), and other indicators for individual level problems, such as alcohol misuse and adaption problems. In light of Moffitt’s (1993) concept of heterotypic continuity, this feature of the CWC data is valuable in capturing a breadth of early deviance, and therefore a particularly important part of our study design when it comes to the validity of adult-onset offending (see also Kratzer & Hodgins, 1999). Another difference between coverage in CWC and INCRI data concerns drug use. Possession, but not use, was considered a criminal offence when the cohort members were in their teenage years. This means that the apprehension of drug use was recorded by the social services and included in the CWC, whereas possession had to be apprehended to lead to a criminal record in INCRI.

Criminal Justice Data

The original Metropolitan study collected individual level crime (INCRI) data from the National Crime Register, administered by the Swedish National Police Board. The first collection was undertaken in 1979 and included the number of crimes reported to the Police between 1966 and the first part of 1979. In 1984, the crime data were updated to also cover the period up to and including the first part of 1984, meaning that INCRI covers ages 13 to 30 for the full cohort (Project Metropolitan, 2005a, 2005b, Codebook IV, p. 35).Footnote 1 The date information in INCRI concerned the date when the crime was committed, not when it was officially registered. Crime was categorized into the following seven crime types: Violence (assault, robbery, rape, molestation, unlawful intrusion), Theft (including receiving stolen goods), Fraud, Vandalism, Traffic (including driving without a license, and driving under the influence of alcohol or narcotics), Narcotic (manufacturing, smuggling, selling and possession), and Other (all other chapters and paragraphs in the penal code or special sanction laws; for specific chapters and paragraphs, see Project Metropolitan, 2005a, 2005b, Codebook IV, pp. 35f).

Conviction data were collected in 2018 as part of the new follow-up of the Metropolitan cohort (Almquist et al., 2019). Conviction data may generally be considered a back-end measure of criminal offending (Nygaard Andersen & Skardhamar, 2017). Still, Swedish conviction data have a relatively broad coverage of criminal offences. In fact, the life-time risk of being convicted for a crime to age 50 was over 40% for males and around 12% for females in cohorts born during the early 1960s (Sivertsson, 2018), making a convicted crime a relatively common “event” in the life course in Sweden. This may be due to a number of reasons. First, Swedish police and prosecutors are bound by the legality principle, meaning that there are no legal grounds for the use of discretion in the handling of criminal offences at apprehension (von Hofer, 2014). With the exception of minor traffic offences, such as speeding, Swedish police are thus bound to report apprehended offences to a prosecutor. The prosecutor then decides whether to take the case to court, or to impose a waiver of prosecution or a summary sanction order, both of which are typically decided in cases without a prison sentence in the penalty scale, and/or when the offender is relatively young. Importantly, both summary sanction orders and waivers of prosecution require that there is no uncertainty with regard to the guilt of the suspect, which in practice means that the suspect has to admit to having committed the crime. In sum then, Swedish conviction data have a relatively high degree of coverage in relation to the number of offences committed, when contrasted to many other countries (von Hofer, 2014).

It should be noted that although INCRI and crime conviction data both originate from the criminal justice system, the former has been available as a processed dataset whereas the latter was extracted directly from the convictions register and therefore constituted raw unprocessed data. For the purpose of comparison, we have as far as possible followed the operationalization of crime made in INCRI (all codebooks can be found at www.stockholmbirthcohort.su.se). Aside from the operationalization of crime types (see above), this also includes the frequency and timing of crime, where we have consistently counted the number of recorded crimes (not convictions), and measured the date of the criminal offence and not the date of the conviction, as there is a lag in studies that use the date of conviction (Farrington, 2003). However, due to differences in definitions and/or coverage between the two registers, we present the two separately when we begin to outline the age/crime relationship in the cohort. As the two registers overlap during a significant age span (20–29), this also presents a validation of the recent data collection and our processing of the conviction data. In the next analyses, however, for pedagogical reasons, we combine the two data sources into criminal justice (CJ) data. For the overlapping age period between ages 20 and 29, we base the measures on conviction data.

Methodological Considerations

Any definitive, and chronological, cut-off age to define the beginning of adulthood is arbitrary (Krohn et al., 2013). We therefore employ Kaplan–Meier cumulative probability functions that provide continuous estimates for the onset of recorded offending (Allison, 2014), in combination with the tabulation of descriptive statistics. The tabulation has, for pedagogical reasons, been based on a fixed cut-off for the chronological definition of adulthood. While previous studies have often used a legal definition of adulthood (i.e., age 18), in line with a number of recent studies we argue that age 25 is a more reasonable cut-off from a developmental point of view (e.g., Beckley et al., 2016). It should, however, be noted that the notion of emerging adulthood is based on middle-class contemporary cohorts, where social adulthood has become postponed as individuals from older cohorts transitioned into typical adulthood markers earlier than younger cohorts (Arnett, 2000). Since we explore crime in a Swedish cohort born in 1953, we therefore want to highlight that 25 may be seen as a conservative cutoff-age to define adulthood in the current study.

Given the long follow-up of the 1953 cohort, decease and migration are two events that need consideration. The cohort is fully covered to age 64 with mortality data and migration data, and the event data used to estimate Kaplan–Meier functions is right-censored at the year of decease and latest recorded year of outmigration (i.e., based on time at risk for a criminal record). The survival curves for mortality and outmigration are presented in Appendix A. In total, around 81.1% of all males and 83.8% of all females in the cohort were alive and had not migrated from Sweden at the age of 64.Footnote 2 The tabulation of the descriptive statistics is based on grouped age-periods and in these analyses we included all individuals who were alive and had not migrated at the beginning of that age-period.

Analytical Strategy

We employ descriptive methods derived from the criminal career approach to present a nuanced profile of crime and criminal careers in the 1953 cohort. Participation and frequency are two fundamental parameters according to this approach, which essentially breaks down the average number of crimes in a cohort into the proportion of the population that was recorded for a criminal event during a given time period (i.e., participation), and the frequency of recorded crimes among recorded offenders during a given time period (Blumstein et al., 1986). Following the criminal career approach, we also present average measures for age of onset, age of termination, and career duration. Age of onset measures the age at the first recorded offence, age of termination measures the age at the finally recorded crime, and career duration is the elapsed time between the two. For purposes of comparison with other criminal career studies, these measures are based on events defined as crime only (i.e., not adaption problems and/or misuse, according to CWC data).

As noted above, we also estimate Kaplan–Meier cumulative probability functions where we take into account the right-censored data due to mortality and outmigration. In essence, this is a non-parametric method that provides estimates for the cumulative proportion of the cohort members at risk (i.e., alive and had not outmigrated) who were convicted of a crime by a given point in time (see Allison, 2014). We first employ this method to provide estimates for the life-time risk of a recorded crime to age 64. This analysis includes all cohort members who were at risk at age 9 (according to CWC records). Process time stopped at the age when the individual was recorded for a crime (i.e., the event), the age at decease, latest recorded outmigration, or age at follow-up (i.e., age 64). Next, we analyzed recidivism and repeated recidivism among adult-onset offenders. In the recidivism analyses, we include all cohort members who were first-time convicted for a criminal offence at age 25 or later and who did not have any CWC record for a crime, adaption problems, or misuse (826 males and 411 females). Consequently, when estimating the risk of repeated recidivism, process time stopped at the date of the next convicted crime (i.e. the event), the year of decease, latest recorded outmigration, or the year at follow-up (i.e. 2018).

Results

Figure 1 illustrates the cumulative life-time risk of being recorded for a crime between ages 9 and 64 among males (a) and females (b).Footnote 3 Following Arnett’s (2000) age typology, we have marked the beginning of adulthood with a dashed vertical line. Almost half (48.1%) of all male cohort members at risk for a criminal record were ever recorded for a crime at age 64. The corresponding figure for female cohort members was 15.3%. The males also display a much steeper increase in the risk of acquiring a criminal record over adolescence and into emerging adulthood; thereafter, a much less steep but relatively stable development across adulthood follows. The females, in contrast, show a more gradual decrease from early adolescence and onwards. This pattern is in line with previous research and confirms that the gender difference in recorded crime is much larger in adolescence and emerging adulthood than in adulthood (see also Andersson et al., 2012; Block et al., 2010; Sivertsson, 2018).

Next, Table 1 shows the number of recorded crimes that the males and females in the Metropolitan cohort have accumulated according to criminal justice records over the full study period (ages 13 to 64) and in adulthood (ages 25 to 64).Footnote 4

First, we should note that, males account for the majority of crimes (around 86.2%). Their overrepresentation is particularly large with respect to vandalism (92.6%) and violent crime (90.8%), and the least so for fraud (around 74%). Importantly, Table 1 shows that a substantial percentage of all recorded criminal offences were committed in adulthood, close to half of all male (46.7%) and around two-thirds of all female crimes (67.2%). In the case of violence, around two-thirds of both male and female offences were committed in adulthood (65.2% and 67% respectively). In the largest crime category, theft, a clear gender difference also emerges: Theft is much more concentrated to adolescence among males than among females — only 28% of all thefts among males were committed in adulthood, compared to 61.9% of all thefts among females.

While crime peaks in adolescence, when it comes to the actual number and share of crimes, a substantial amount does occur in the stage of adulthood. The extent to which these crimes can be traced back to former juvenile delinquents, suggesting continuity, or to de novo adult-onset offenders is a theme we return to later. First, we study the age/crime relationship, and the overall criminal careers among the Metropolitan males and females to age 64.

Age and Crime to Age 64 Among Males and Females Born in 1953

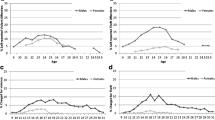

Figure 2 shows age/crime participation curves from ages 9 to 64 among males (a) and females (b). For males, the typical age/crime pattern emerges, that is, an increase through the early years of adolescence up to a peak in late adolescence/early 20s. Then a marked decrease over emerging adulthood follows, and a more modest decrease across adulthood. There is a clear coherence between the three registers, although the CWC data captures less crime in late adolescence compared to the INCRI, and conviction data displays a somewhat higher participation than INCRI during the cohort’s twenties.

As can be seen in Fig. 2b, the female participation level is much lower than the male across the full life span, but particularly so in adolescence and emerging adulthood. Interestingly, comparing CWC and INCRI data reveals that, in contrast to the males, a much larger proportion of females were apprehended and recorded for criminal offences by the Social Services than by the criminal register. Seen across all three registers, this suggests that the modal peak age of criminal offending occurred earlier among females than among males, a finding which deviates from many other studies relying on criminal justice data (e.g., Block et al., 2010; Sivertsson, 2018) and is more in line with studies using alternative sources for criminal offending and antisocial behavior (e.g., Moffitt et al., 2001). This peak, it should be noted, is primarily driven by young females’ narcotic offences.Footnote 5 In other words, the original hypothesis of the taxonomy that females should engage in antisocial behavior before males do due to the dynamics of puberty and the maturity gap is supported by our data. The decline across adulthood is also less distinct among females than among males, a finding mirrored in previous studies of gender and criminal careers (Estrada & Nilsson, 2012).

Criminal Career Parameters to Age 64

Following the criminal career approach, we now turn to the different components of the age/crime curve, that is, age of onset, age of termination, career duration, participation, and individual crime frequency. In Table 2a–b, we present participation and frequency in overall crime and by crime categories according to the CWC data (ages 9 to 19) and CJ data (ages 13 to 64) respectively.Footnote 6 Thus, 19% of the males and 5.5% of the females were recorded for a crime in the CWC data. Theft was the most common crime category among both males (14.7%) and females (3.6%) followed by traffic crimes among males (4.7%) and narcotic crimes among the females (2.3%). Males were overrepresented in all crime categories, but less so in narcotic crimes. Also, the overrepresentation of males in recorded adaption problems is not as distinct as when it comes to most crime categories (5.4% and 3.8% respectively). Turning to the CJ data, 45.1% of the males and 12.9% of the females were ever recorded for a crime between ages 13 and 64. Traffic crime was most prevalent among the males (22.9%) whereas theft was most prevalent among females (6.1%).

Overall, as we know from previous studies on crime and gender, males are heavily overrepresented in the prevalence of crime over the life course according to the CJ data. When analyzing individual crime frequency, the most apparent change compared to the previous participation measures is that the gender differences are much smaller, particularly when comparing CWC records in youth. This is in line with many other studies which direct attention to gender similarities and differences in criminal careers (e.g., Block et al., 2010). As noted, analyzing the Metropolitan cohort in 1990, Wikström (1990: 72) reached the same conclusion and stated that “there is practically no [gender] difference in crimes per offender rates at the oldest ages.” It should be noted that the frequency is actually higher for females in narcotic crime according to both CWC and CJ records, and in the case of fraud according to CJ data.

Table 3a–b presents age of onset, age of termination, and career duration based between ages 9 and 64. Compared to females, males have, on average, an earlier age of onset (21.6 and 25.1 respectively), a later age of termination (32.3 and 31.3 respectively), and thus also longer career duration (10.7 and 6.1 respectively). Males’ comparatively earlier age of onset may seem contradictory when considering Fig. 1, but — as we show later — the peak age of offending among the females does not generate any noticeable shift in their mean age of onset across the full study period, due to the relatively high percent of adult-onset offenders in the female offender pool. In other words, the findings in Table 3 align relatively well with comparative longitudinal datasets from other countries, such as the UK (e.g., Prime et al., 2001) and New Zealand (Mazerolle et al., 2000). There is notable dispersion around these average measures, however, indicating a substantial heterogeneity in individual criminal careers.

As a final step at this stage of analysis, Fig. 3 shows the association between age of onset and career duration (a) and crime frequency (b) by gender.

As expected, while a number of year-to-year discrepancies can be observed, a clear association emerges, where both males and females with an early onset exhibit longer and more frequent careers in crime. For those whose onset occur very early, however, a distinct gender difference can be observed in terms of frequency, with a clear association between age of onset and frequency for males, but less so for females. However, for those whose onset occur around or after the normative peak of delinquency in late adolescence, the frequencies are very similar in males and females. In general, males and females exhibit similar patterns of career duration and frequency with regard to age of onset. These findings indicate a highly skewed crime distribution among both male and female offenders in the cohort, where those with a very early onset of crime will account for the majority of all offences.

The Criminal Careers of Adult-Onset Offenders

We now turn specifically to the adult-onset offender. Of all male and female offenders in the cohort, around 23% of the males and 38% of the females were first-time convicted in adulthood. Table 4a–b shows criminal career measures between ages 25 and 64 in these respective offender groups. To be clear, the adult-onset males and females in Table 4 did not have any CWC record for crime, misuse, or adaption problems during ages 9 to 19.

Compared to the overall criminal careers (Table 3), the criminal career of the adult-onset offender is markedly less frequent and also shorter. The adult-onset males were on average convicted for 2.4 crimes and had a career duration of, on average, around 3.5 years, whereas the figures among adult-onset females were 2.2 crimes and 2.3 years. It should, however, be noted that the dispersion around the criminal career means suggests that there is some degree of meaningful variation among the adult-onset offenders too. When it comes to the offences they were convicted for, the largest category was traffic crime, for which around 42% of the males and 39% of the females were convicted. The main gender difference in the crime mix was that a violent crime was more common in adult-onset males whereas a theft crime was more common in adult-onset females.

Table 4 also shows how much of the total number of crimes per crime category that the adult-onset males and females contributed to in adulthood within their respective populations. As can be seen, the lion’s share of all adult crime is committed by offenders who debuted prior to age 25, and this is particularly the case among the males. Still, a non-negligible share of adult crimes is accounted for by adult-onset offenders. Among the males, adult-onset offenders account for 11.2% of all male crimes in adulthood; the corresponding percentage among the females is 22.3%. These results are in line with the few previous studies that compared male and female adult-onset offenders, where adult-onset females contributed much more to total adult crime among females than did adult-onset males among males (Beckley et al., 2016; Sivertsson, 2018). The variation is quite large between different crime types and there are clear gender differences in this regard. The category to which adult-onset females contributed the most was violent crime (32.2%) whereas the category to which adult-onset males contributed the most was fraud (14%). The contribution to theft crime in adulthood was very small for the adult-onset males (4.2%) whereas the adult-onset females contributed 19.7% of all female thefts in adulthood.

Finally, to explore variation in adult-onset criminal careers, we turn to the risk of recidivism and repeated recidivism. Figure 4a–b illustrates cumulative probability functions of recidivism over a 10-year period in adult-onset males and females respectively.

The pattern of adult-onset offenders’ reconviction risks thus replicates the well-known growth in reconviction probabilities in general, which we recognize from the criminal career literature (e.g., Piquero, Farrington, and Blumstein, 2007), and shows clear gender similarities. The reconviction risk (over a 10-year period) was around 20% among first-time convicted adult-onset males and females. Turning to repeated recidivism, over a 10-year period, the risk was around 53% for males and close to 60% for females, i.e., higher for females than males. In other words, whereas a majority of adult-onset offenders are convicted only once, a non-negligible proportion of these continue into recidivism. Finally, among those who recidivate, the risk for repeated recidivism is high. Again, this suggests a meaningful variation in adult-onset offenders that should be explored further.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to, descriptively and exploratory, trace the criminal histories of 14,608 males and females in a full Stockholm birth cohort born in 1953 to age 64, covering as much of the full arc of life as data allowed. Since studies with such long follow-up periods are rare within developmental and life-course criminology (e.g., Farrington, 2019; LeBlanc, 2020; Laub & Sampson, 2003), our study adds to the existing literature on long-term criminal careers in general, and on adult-onset offending and male and female criminal careers in particular.

We began by studying the cumulative life-time risk of being recorded for a crime in the full cohort to age 64, finding that nearly half of all males and 15% of all females were convicted at least once. This estimate lies very close to other longitudinal studies of crime with similar follow-up periods (e.g., Farrington et al., 2021), and suggests that quite a substantial proportion of the general population of males may be expected to become convicted for a crime over their lives. While the aggregate age/crime curve showed that crime participation peaks in adolescence, as expected, the main bulk of crimes recorded in the cohort occurred after the dawning of adulthood; indeed, nearly half of all male crimes and more than two-thirds of all female crimes in the cohort are committed after the age of 25. In the case of violence, the majority of violent offences — around two-thirds for both genders — in the cohort took place not in adolescence, but in adulthood. This indicates that adulthood is an important stage of the life course for criminal career researchers, and explaining adult criminal offending should be a high priority for life-course criminological theory.

Moreover, while a substantial share of all recorded adult crime can be referred to previously known offenders, our findings suggest that a non-negligible proportion of males and females were convicted for their first time at age 25 or later — around 23% of all males with a criminal record in the 1953 cohort were first recorded for a criminal offence in adulthood; for females, the number was around 38%. These figures are slightly lower compared to a previous Swedish study, which followed a somewhat younger generation of males and females born during the first half of the 1960s with conviction data between ages 15 and 50 (Sivertsson, 2018). Importantly, while that study was limited by only being able to measure crime as captured in convictions data from age 15 and onwards, and thereby could not account for undetected crime in early adolescence (see Sohoni et al., 2014), the adult-onset males and females in the current study had no record at all in neither CWC (including delinquency, adaption problems, or alcohol/drug misuse) nor CJ data between ages 9 and 24. This, we argue, strengthens the validity for the phenomenon of adult-onset offending (see also Kratzer and Hodgins, 1999).

CWC data, of course, does not extinguish the risk for undetection, and, thus, it is possible, even likely, that a number of cohort members who were involved in some form of delinquency during adolescence went unnoticed into the phase of adulthood, where they were first recorded and convicted. Indeed, studies using both self-reported and official data to examine adult-onset offending have found that a proportion of those who were arrested and convicted for the first time in adulthood had unofficial histories of criminal offending in adolescence. However, skepticism toward the concept of adult-onset offending on the basis of these findings has to be related to the fact that sporadic, non-serious delinquency is so common that even those who are never recorded for criminal offending tend to have self-reported it in adolescence (McGee & Farrington, 2010). If anything, it is unlikely that the relatively large proportion of adult-onset offenders and their share of adult crime in the current study could be accommodated by the LCP theory. Following the logic of heterotypic continuity (Moffitt, 1993), this would essentially mean that individuals whose persistence in antisocial behavior starts in early childhood and continues through adolescence (and who often grow up in a criminogenic environment) would somehow remain undetected by the Social Services and from a criminal record to age 25. Some share of adult-onset offending could probably be better accommodated by the AL theory, because the criminal careers of adult-onset offenders are similar to those of adolescence-limited offenders in that they tend to be brief and non-serious (Moffitt, 2006, p. 287).

However, our results also suggest meaningful variation in terms of criminal careers within the population of adult-onset offenders. While the majority of adult-onset offenders in the Stockholm cohort were convicted only once, a non-negligible proportion continue into recidivism and repeated recidivism — over a 10-year period, the risk for recidivism was around 20% for both adult-onset males and females. Among adult-onset recidivists, the risk for repeated recidivism over a 10-year period was high at around 60%. In other words, the general tendency for growing reconviction probabilities in a cohort of offenders was also present in adult-onset offenders. Again, it is unlikely that these recidivism processes can be accounted for by individual selection on early static risk factors; rather, they seem to indicate the possible presence of negative turning points. More generally, this heterogeneity in adult-onset offenders resonates well with Laub and Sampson’s (2003) assertion that explanations should be sought in the near, social context of the criminal event.

Our study also adds to the knowledge base on gender and criminal careers. In line with previous longitudinal studies on male and female crime across the life course, we found a set of clear gender differences (e.g., Block et al., 2010). Not surprisingly, seen across the full study period, males had a much higher participation rate and also offended at a higher frequency. Males also had an earlier onset of recorded crime, and a somewhat later termination, thus resulting in a longer career duration than females. When it comes to frequency, males with an early onset of crime offended at a much higher frequency than did females with a similar onset, echoing previous findings that chronic offending is much more prevalent in males (e.g., Block et al., 2010). These findings are much in line with the predictions made by Moffitt’s (1993) taxonomy (see Moffitt et al., 2001). However, the overall gender differences in criminal career parameters in the Stockholm birth cohort were mainly driven by differences in adolescence; when focusing on adulthood alone, gender differences become much smaller. Those males and females who were first time recorded for a criminal offence in mid-adolescence and beyond had close to identical frequencies (and career durations). Moreover, when studying the adult-onset offenders’ risk of recidivism and repeated recidivism, results were nearly identical across gender. This is not to say that explanations for adult-onset offending are necessarily gender-neutral, but rather, that future studies on the adult onset of crime and subsequent recidivism should not exclusively focus on the male population.

The prediction of the taxonomy that females should have an earlier onset of antisocial behavior than males since they enter puberty earlier has been challenged by prior studies on the basis that females, on average, tend to have a later onset of crime than males (e.g., Beckley et al., 2016; Block et al., 2010; Sivertsson, 2018). In this study, too, the mean age of onset was later in females, and adult-onset offending was considerably more prevalent in the female offender population (38% of all convicted females in the cohort) than in the male counterpart (23% of all convicted males). Interestingly, and in line with the prediction made by the AL theory concerning gender differences, we found that the modal peak of delinquency and antisocial behavior, according to CWC, actually occurred earlier in females than in males. This should be seen in light of the fact that the prevalence differences in CWC and Police records among females were much larger than for males, suggesting that female antisocial behavior, relative to boys’ antisocial behavior, was to a higher degree handled by the Social Services than by the criminal justice authorities. In other words, it may be that prior studies using official crime data to contrast female and male criminal careers have been particularly limited when it comes to capturing the early onset of female antisocial behavior.

Finally, the cohort we traced in this study was born in Stockholm in 1953, grew up in the 1960s, and entered adulthood in the late 1970s (Stenberg, 2018). As noted, for a Swedish cohort born in 1953, marking the transition to adulthood at age 25 is highly conservative, but for comparative purposes, we found it illustrative. Additionally, consider drug use and narcotic offences. In Sweden, drug use emerged as a social problem during the 1960s and 1970s, culminating in the political idea of a “drug-free society” and a repressive Swedish drug policy (e.g., Lenke & Olsson, 2002). While considered a social problem which authorities such as the CWCs reacted to, personal drug use was not formally criminalized until 1988. In our measures of the cohort’s criminal careers, this may be mirrored in the contrast between the CWC data (where drug use is relatively prevalent) and data from the criminal justice system (where it is not). Such contextual elements are of course present in, and inform all longitudinal studies (for an extensive description of the SBC and the 1953 cohort in this regard, see Stenberg, 2018).

Implications

Adulthood is an important stage of the life course for criminal career researchers and explaining adult criminal offending should be a high priority for life-course criminological theory. Whereas some (e.g., Gottfredson & Hirschi, 1990; Moffitt, 1993; Raine, 2013) argue that this can be done by focusing on traits and circumstances which occur in the earliest stages of life and then unfold in processes of both contemporary and cumulative continuity, others adopt a more dynamic, situational perspective and suggest a more complex interaction between the past and the present (e.g., Laub & Sampson, 2003; Wikström et al., 2012).

Criminal offending taking place in adulthood very often does have a history of subsequent criminal offending, i.e., it is a sign of behavioral continuity and/or cumulative disadvantage (Moffitt, 1993; Sampson & Laub, 1997). After all, in our study too, roughly 9 out of 10 male crimes in adulthood were committed by males with a history of offending prior to age 25; for females, the same number was 8 out of 10. However, the aggregate crime/curve also seems to be in part constituted by individuals who engage in crime after the advent of adulthood — in this study, more than one in every five male offenders and nearly two in every five female offenders appear to initiate criminal offending in adulthood.

Such findings seem to align with the life-course principle of life-span development, which highlights that life does not simply unfold, but is a dynamic process where adults, as well as adolescents, experience fundamental biological, psychological, and social changes that are developmentally important (Elder et al., 2003). As such, they may have a considerable impact on criminal offending. In other words, to deepen our understanding and to refine our explanations of criminal careers in adulthood, understanding the prevalence, causes, and correlates of adult-onset offending may prove to be key. Studies focusing on what Sampson and Laub (1993) termed potential negative turning points, which may lead to within-individual changes in criminal offending in adulthood, are very much needed. Finally, the male and female career patterns observed in this study suggest the need for further explorations of both gender-specific and generic explanations of crime.

Notes

To make sure that INCRI covers the whole 1953 cohort, born during the full calendar year, and to capture a 10-year overlap in data coverage, we only use INCRI data up to age 29.

A more detailed migration history was not available in the data, and it should thus be noted that there is a small proportion of individuals who migrate from and to the country back and forth. Still, given the old cohort and the fact that Sweden was not at this point in time a country of migration, this group should be very small and not render any substantial difference to the results.

To clarify, we measure the age at which the first criminal record was recorded in any of the three registers: CWC covering ages 9 to 19, INCRI covering ages 13 to 29, and convictions data covering ages 20 to 64. The data is right-censored at the age of decease. The mortality rate among males and females to age 64 was 11.4% and 6.8% respectively.

These figures do not include crimes recorded in CWC data. As noted in the “Data and Methods” section, CWC records are based on the number of interventions made by the social authorities and not the number of crimes committed by the child. Therefore, those counts are not comparable to CJ data.

For clarity, a breakdown of overall crime into violent, theft, and narcotic crime is shown in Appendix, Fig. 2. There is a consistent overlap between the three registers, with one exception. For narcotic crimes, the CWC data has captured a much higher number of juveniles than INCRI, and this is particularly the case among females. While INCRI records for narcotic crimes display a relatively flat age/crime curve, the curve shows a distinct peak in adolescence when considering the CWC data. As noted earlier, drug use was not considered a criminal offense at the time, but could lead to an investigation from the social sevices. Naturally, this contributes to the observed differences between INCRI and CWC data with respect to narcotics offenses.

The prevalence figures in Table 2 are slightly lower than those in Fig. 1. The reason for this is that the Kaplan–Meier cumulative probability functions handle right-censoring due to mortality whereas all cohort members who were alive at the beginning of the register are included in the denominator for the prevalence calculation in Table 2.

References

Allison, P. D. (2014). Event history and survival analysis. Sage.

Almquist, Y. B., Grotta, A., Vågerö, D., Stenberg, S. -Å., & Modin, B. (2019). Cohort profile update: The Stockholm Birth Cohort Study. International Journal of Epidemiology, 49(2), 367–367e.

Andersson, J. (1990). Continuity in crime: Sex and age differences. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 6(1), 85–100.

Andersson, F. (2013). The female offender: Patterning of antisocial and criminal behaviour over the life-course. Malmö Högskola

Andersson, F., Levander, S., Svensson, R., & Levander, M. T. (2012). Sex differences in offending trajectories in a Swedish cohort. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 22(2), 108–121.

Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55(5), 469–480.

Beckley, A. L., Caspi, A., Harrington, H., Houts, R. M., McGee, T. R., Morgan, N., Schroeder, F., Ramrakha, S., Poulton, R., & Moffitt, T. E. (2016). Adultonset offenders: Is a tailored theory warranted? Journal of Criminal Justice, 46, 64–81.

Belsky, J., Caspi, A., Moffitt, T. E., & Poulton, R. (2020). The origins of you: How childhood shapes later life. Harvard University Press.

Bergman, L. R., & Andershed, A.-K. (2009). Predictors and outcomes of persistent or age-limited registered criminal behavior: A 30-year longitudinal study of a Swedish urban population. Aggressive Behavior, 35(2), 164–178.

Block, R. C., Blokland, A. A. J., van der Werff, C., van Os, R., & Nieuwbeerta, P. (2010). Long-term patterns of offending in women. Feminist Criminology, 5, 73–107.

Blumstein, A., Cohen, J., Roth, J. A., & Visher, C. A. (1986). Criminal careers and career criminals. National Academy Press.

Britt, C. L. (2019). Age and crime. In: The Oxford handbook of developmental and life-course criminology, eds. David P. Farrington, Lila Kazemian, and Alex R. Piquero. Oxford University Press

Chesney-Lind, M., & Pasko, L. (2012). The female offender. Sage.

Cullen, F. T. (2011). Beyond adolescence-limited criminology: Choosing our future—The American Society of Criminology 2010 Sutherland address. Criminology, 49(2), 287–330.

DeLisi, M., & Piquero, A. R. (2011). New frontiers in criminal careers research, 2000–2011: A state-of-the-art review. Journal of Criminal Justice, 39(4), 289–301.

DeLisi, M., Tahja, K. N., Drury, A. J., Elbert, M. J., Caropreso, D. E., & Heinrichs, T. (2018). De novo advanced adult-onset offending: New evidence from a population of federal correctional clients. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 63(1), 172–177.

Eggleston, E. P., & Laub, J. H. (2002). The onset of adult offending: A neglected dimension of the criminal career. Journal of Criminal Justice, 30(6), 603–622.

Elder, G.H., Jr., Johnson, M.K., & Crosnoe, R. (2003). The emergence and development of life course theory. In: Mortimer, J.T., & Shanahan, M.J. (eds) Handbook of the life course. Springer

Estrada, F., & Nilsson, A. (2012). Does it cost more to be a female offender? A life-course study of childhood circumstances, crime, drug abuse, and living conditions. Feminist Criminology, 7(3), 196–219.

Farrington, D. P. (1986). Age and crime. Crime and Justice, 7, 189–250.

Farrington, D. P. (2003). Developmental and life-course criminology: Key theoretical and empirical issues-the 2002 Sutherland Award address. Criminology, 41(2), 221–225.

Farrington, D. P. (2005). Integrated developmental and life-course theories of offending. Advances in criminological theory, Vol. 14. Transaction Publishers

Farrington, D. P. (2019). The development of violence from age 8 to 61. Aggressive Behavior, 45(4), 365–376.

Farrington, D. P., Piquero, A. R., & Blumstein, A. (2007). Key issues in criminal career research. Cambridge University Press.

Farrington, D. P., Ttofi, M. M., Crago, R. V., & Coid, J. W. (2014). Prevalence, frequency, onset, desistance and criminal career duration in self-reports compared with official records. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 24(4), 241–253.

Farrington, D. P., Jolliffe, D., & Coid, J. W. (2021). Cohort profile: The Cambridge Study in delinquent development. Journal of Developmental and Life-Course Criminology, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40865-021-00162-y

Gomez-Smith, Z., & Piquero, A. R. (2005). An examination of adult onset offending. Journal of Criminal Justice, 33(6), 515–525.

Gottfredson, M. R., & Hirschi, T. (1990). A general theory of crime. Stanford University Press.

Janson, C-G. (1975). Project Metropolitan: A presentation. Project Metropolitan Research Report. No. 1. Stockholm University

Janson, C-G. (1980). Register Data I. A code book. Project Metropolitan Research Report No 12. Stockholm University

Jolliffe, D., Farrington, D. P., Piquero, A. R., MacLeod, J. F:, & van de Weijer, S. (2017). Prevalence of life-course-persistent, adolescence-limited, and late-onset offenders: A systematic review of prospective longitudinal studies. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 33, March-April: 4–14.

Kratzer, L., & Hodgins, S. (1999). A typology of offenders: A test of Moffitt’s theory among males and females from childhood to age 30. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 9(1), 57–73.

Krohn, M. D., Gibson, C. L., & Thornberry, T. P. (2013). Under the protective bud the bloom awaits: A review of theory and research on adult-onset and late-blooming offenders. In Gibson, C. L. & Krohn, M. D. (eds). Handbook of life-course criminology. Springer

Laub, J. H., & Sampson, R. J. (2003). Shared beginnings, divergent lives: Delinquent boys to age 70. Harvard University Press.

Le Blanc, M. (2020). On the future of the individual longitudinal age-crime curve. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, https://doi.org/10.1002/cbm.2159

Lenke, L., & Olsson, B. (2002). Swedish drug policy in the twenty-first century: A policy model going astray. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 582, 64–79.

Mazerolle, P., Brame, R., Paternoster, R., Piquerp, A., & Dean, C. (2000). Onset age, persistence, and offending versatility: Comparisons across gender. Criminology, 38(4), 1143–1172.

McGee, T. R., & Farrington, D. P. (2010). Are there any true adult-onset offenders? British Journal of Criminology, 50(3), 530–549.

Moffitt, T. E. (1993). Adolescence-limited and life-course persistent antisocial behavior: A developmental taxonomy. Psychological Review, 100(4), 674–701.

Moffitt, T.E. (2006). A review of research on the taxonomy of life-course persistent versus adolescence-limited antisocial behavior. In: Cullen, F.T., Wright, J.P. & Blevins, K.R. (eds) Taking stock: The status of criminological theory. Transaction.

Moffitt, T. E. (2018). Male antisocial behaviour in adolescence and beyond. Nature Human Behaviour, 2, 177–186.

Moffitt, T. E., Caspi, A., Dickson, N., Silva, P., & Stanton, W. (1996). Childhood-onset ersus adolescent-onset antisocial conduct problems in males: Natural history rom ages 3 to 18 years. Development and Psychopathology, 8(2), 399–424.

Moffitt, T. E., Caspi, A., Rutter, M., & Silva, P. A. (2001). Sex differences in antisocial behaviour. Cambridge University Press.

Nilsson, A., Estrada, F., & Bäckman, O. (2014). Offending, drug abuse and life chances: A longitudinal study of a Stockholm birth cohort. Journal of Scandinavian Studies in Criminology and Crime Prevention, 15(2), 128–142.

Nygaard Andersen, S., & Skardhamar, T. (2017). Pick a number: Mapping recidivism measures and their consequences. Crime & Delinquency, 63(5), 613–635.

Piquero, A. R. (2008). Taking stock of developmental trajectories of criminal activity over the life course. In The long view of crime: A synthesis of longitudinal research (pp. 23–78). Springer

Project Metropolitan. (2005a). Codebook II. Available Online via: https://www.su.se/polopoly_fs/1.525289.1604578693!/menu/standard/file/Codebook_II.pdf. Accessed 3 Oct 2020

Project Metropolitan. (2005b). Codebook IV. Available Online via: https://www.stockholmbirthcohort.su.se/polopoly_fs/1.63715.1323440987!/menu/standard/file/Codebook_IV.pdf. Accessed 3 Oct 2020

Raine, A. (2013). The anatomy of violence: The biological roots of crime. Pantheon.

Sampson, R. J., & Laub, J. H. (1993). Crime in the making: Pathways and turning points through life. Harvard University Press.

Sampson, R.J., & Laub, J.H. (1997). A life-course theory of cumulative disadvantage and the stability of delinquency. In: Thornberry, T. (ed) Developmental theories of crime and delinquency. Transaction Publishers.

Sapouna, M. (2017). Adult-onset offending: A neglected reality? Findings from a contemporary British general population cohort. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 61(12), 1392–1408.

Schwartz, J., & Steffensmeier, D. (2017). Gendered opportunities and risk preferences for offending across the life-course. Journal of Developmental and Life-Course Criminology, 3, 126–150.

Sivertsson, F. (2018). Adulthood-limited offending: How much is there to explain? Journal of Criminal Justice, 55, 58–70.

Sivertsson, F., & Carlsson, C. (2015). Continuity, change, and contradictions: Risk and agency in criminal careers to age 59. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 42(4), 382–411.

Sohoni, T., Paternoster, R., McGloin, J. M., & Bachman, R. (2014). ‘Hen’s teeth and horse’s toes’: The adult onset offender in criminology. Journal of Crime and Justice, 37(2), 155–172.

Stenberg, S. -Å. (2018). Born in 1953: The story about a post-war Swedish cohort, and a longitudinal research project. Stockholm University Press.

Stenberg, S. -Å., & Vågerö, D. (2006). Cohort profile: The Stockholm birth cohort of 1953. International Journal of Epidemiology, 35(3), 546–548.

von Hofer, H. (2014). Crime and reactions to crime in 34 Swedish birth cohorts: From historical descriptions to forecasting the future. Journal of Scandinavian Studies in Criminology and Crime Prevention, 15(2), 167–181.

Wikström, P.-O.H. (1990). Age and crime in a Stockholm cohort. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 6(1), 61–84.

Wikström, P.-O.H., Oberwittler, D., Treiber, K., & Hardie, B. (2012). Breaking rules: The social and situational dynamics of young people’s urban crime. Oxford University Press.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Stockholm University. This work was funded by the Swedish Research Council (Grant No. 2018–01452).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Carlsson, C., Sivertsson, F. Age, Gender, and Crime in a Stockholm Birth Cohort to Age 64. J Dev Life Course Criminology 7, 359–384 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40865-021-00172-w

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40865-021-00172-w