Abstract

Mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) have been evaluated in terms of efficacy; however, little is known about implementation factors of MBIs in schools. The purpose of the current study was to systematically review MBI studies published in school psychology journals. This systematic review examined peer-reviewed MBI literature in nine school psychology journals from 2006 to 2020 to examine prevalence of MBI intervention studies, specific techniques taught in MBIs, if and how fidelity of MBI implementation was evaluated, and how mindfulness skills were measured for youth participating in MBIs. A total of 46 articles (out of 4415) were related to mindfulness and 23 articles (0.52%) focused on the implementation of MBIs in schools. Nine different mindfulness techniques were implemented as part of MBIs in studies with some of the most common including awareness, breathing, and meditation. This study also found scarce evidence of implementation fidelity, and limited use of mindfulness measures within MBI studies. Future research and limitations are also discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Brief History of Mindfulness in the United States

Mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) became a secularized practice of Buddhist traditions when Jon Kabat-Zinn brought the practice to the western world at the end of last century (Sun, 2014). As a research-based practice, secular mindfulness started with the mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) program, a psychological treatment for chronic illness for adults in the 1990s (Kabat-Zinn, 1990). From there, mindfulness in the United States (U.S.) evolved as an evidence-based intervention for mental health disorders, such as depression and anxiety, with the gold standard program mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT; Segal et al., 2002). In the last decade, secular mindfulness practices have been introduced to the public to prevent and support mental health in daily life (e.g., Khoury et al., 2015).

While mindfulness started to accumulate evidence for its effectiveness, other scholars were concerned with understanding the underlying mechanisms of action or change and definitions of mindfulness were offered. Bishop et al. (2004) offered one of the first, and widely used operationalized definition. According to the authors, mindfulness requires two components: (1) self-regulation of attention, that is oriented to the present moment, and (2) responding to the events with curiosity, openness, and acceptance (Bishop et al., 2004).

Further, Shapiro et al. (2006) proposed a three-axiom model of mechanisms that could explain how mindfulness works. The three are axioms: (1) intention, purposeful; (2) attention, observing moment to moment; (3) attitude, mindfulness qualities such as acceptance, compassion, kindness. Together they could explain the underlying mechanism of mindfulness (Shapiro et al., 2006). The work of Bishop et al. (2004) and Shapiro et al. (2006) were critical to bolster American mindfulness academic research, which also extended to practice.

Mindfulness in Schools

In considering mindfulness and what MBIs mean for youth, researchers have put forth similar definitions that have been used for adults. For example, Klingbeil et al. (2017) suggested that mindfulness is a compendium of skills, hence they can be taught and measured. Additionally, Renshaw (2020) recently proposed that mindfulness is comprised of two main components: (1) present to moment awareness (PMA; e.g., noticing sensations in the body); and (2) responding with acceptance (RWA; e.g., practicing kindness when feeling frustrated). In this sense, PMA relates to the practice of orientating the attention to the present moment and RWA comprises the mindfulness qualities that are associated to the experience of awareness. Renshaw and Cook (2017) suggested that mindfulness is a practice in itself, but can also be used within intervention programs. According to their definition, it is a technique that actives a mindfulness process to improve a specific outcome. Furthermore, they suggest that mindfulness within intervention can include “…specific practices that active mindfulness processes, such as mindful breathing or the mindful body scan exercise, for the purpose of achieving an immediate therapeutic effect…” (pp. 6). Although various techniques are considered to facilitate mindfulness (e.g., deep breathing), limited research has closely examined what techniques are included or taught within MBIs for youth.

Previous Systematic Reviews

Although many mindfulness techniques have been examined for use with adults, research on MBIs or mindfulness techniques for children began in the 1990s and is less developed than the adult counterpart. In 2008, Thompson and Gauntlett-Gilbert wrote perhaps one of the first reviews on mindfulness intervention for children describing efficacy and implications for future practice. The authors found limited empirical studies in their review, which emphasized the need at the time for more rigorous research to understand the effects on children. Black et al. (2009) focused their review on sitting meditation with children and adolescents, finding medium effect sizes for psychological outcomes. That same year, Burke (2010) published a systematic review focusing only on mindfulness-based interventions, such as MBSR and MBCT, for children and adolescents. Burke (2010) reviewed a total of 15 studies that highlighted the feasibility of these interventions for the younger population; however, just like previous reviews, Burke (2010) also noted the infancy of the methodology (e.g., rigor of controls, research design) used in the reviewed studies. No information about the specific mindfulness skills or techniques were discussed.

Growing interest and implementation of MBIs in schools began to occur in the early 2000’s when Napoli et al. (2005) conducted the first empirical study in school, a randomized controlled trials of 6 months of mindfulness training sessions to students in grades K through 3, finding increased attention and social skills (Renshaw & Cook, 2017). A decade later, Zenner et al. (2014) published the first systematic review and meta-analysis of MBIs in schools, including 24 studies with 19 of those being published articles. The work of Zenner et al. (2014) highlighted the growth of interest in mindfulness interventions for the school community, finding positive pooled effect sizes of different psychological outcomes like attention (g = 0.80), resiliency (g = 0.36), and stress (g = 0.39). A few years later, Klingbeil et al. (2017) replicated and extended the findings of previous work. They found 76 studies, with 46 of those being conducted at a school setting. Klingbeil et al. (2017) reported that mindfulness in schools continues to grow, with small positive effects for internalized problems (g = 0.39), externalized problems (g = 0.29), and social competence (g = 0.36).

Given the increase of complexity and rigor of empirical studies, and the findings of several authors summarizing outcomes for students in schools, Renshaw et al. (2017) suggested that MBIs are an empirical based intervention. A meta-analysis by Dunning et al. (2019), only included randomized controlled trials (RCTs). which is the most methodologically stringent meta-analysis or systematic review in this area published so far, found positives changes in student variables such as mindfulness, attention, depression, anxiety/stress, and negative behaviors. Over a decade of studies have found that MBIs are safe, feasible and efficient in supporting social emotional outcomes in children and adolescent, with school psychologists having an important role in schools (Renshaw et al., 2017).

To this point, Bender et al. (2018) reviewed the mindfulness literature being published in the school psychology field through a systematic review of nine school psychology journals. Bender et al. (2018) noted an increase on overall mindfulness literature (e.g., theoretical, conceptual, review papers) and empirical studies investigating MBIs from 2006 to 2016. Their findings suggest that MBIs were most frequently implemented at the universal level (Tier 1), serving students from elementary to high school, and focused on students’ social-emotional/behavioral outcomes. Overall, the current literature suggest that mindfulness can be a feasible and effective intervention to support emotion regulation, attention, and other internalized and externalized behaviors in students.

Previous systematic reviews have evaluated outcomes of MBI and the effects it has on students (e.g., Felver et al., 2016). While this is critical to advance the field and establish mindfulness as an evidence-based intervention, there are other components of MBI implementation that are yet to be understood and researched (Renshaw, 2020). One of these areas of MBI implementation in schools that require examination of are the techniques used within MBIs. Techniques within MBIs can include specific practices that active mindfulness processes (Renshaw & Cook, 2017) and can involve different types of skills or techniques to achieve this effect. Crane et al. (2017) proposed three core principles for practicing mindfulness for adults: body scan, mindful movement and sitting meditation. In a recent systematic review evaluating MBIs that included these three core components, Emerson et al. (2020) found that less than a half of studies they reviewed (n = 31) reported utilizing these techniques. While they noted this as problematic, they did not provide further information on the types of techniques being implemented. In addition to these techniques (Crane et al., 2017), heartful techniques such as kindness and compassion (Rosenzweig, 2013) are considered to facilitate mindfulness and have been taught in MBIs (e.g., A mindfulness-based kindness curriculum; Center for Healthy Minds, 2017). Although there is flexibility in the techniques taught to facilitate mindfulness, limited research has examined the frequency and extent to which these ingredients are included in MBIs in schools for youth.

In Emerson et al.’s (2020) systematic review on MBI implementation research, the authors noted consistent findings on feasibility and effectiveness of different MBI programs, however several implementation elements were emphasized as needing further development. Among those elements, implementation fidelity and identifying mechanisms of change in MBIs in empirical studies were presented as crucial in order to truly generalize findings and advance the evidence of the field. Both of these elements have been largely missing from previous systematic reviews.

Treatment fidelity or implementation fidelity refers to the extent to which an intervention was implemented as intended. Emerson et al. (2020) commented on the limited information that researchers have provided in the area of treatment fidelity. For instance, Gould et al. (2016) found insufficient presence of implementation fidelity reports on MBIs research in schools. While 63% of studies indicated some form fidelity, only 20% reported a measure beyond participant’s attendance in the program. Previous reviews of MBIs in schools have not reported fidelity data, making it difficult to understand how well are MBIs implemented and how fidelity data may be impacting observed outcomes.

Lastly, the underlying mechanisms (or mechanisms of change) of mindfulness is still at its infancy stages in research. With the rising popularity of mindfulness there is a call to understand the mediator between MBIs and outcomes for youth (Renshaw, 2020). One fundamental way of understanding changes in mindfulness is through measuring the variable itself. Several measures have been created for youth (e.g., Abujaradeh et al., 2020; Briere, 2011; Greco et al., 2011; Johnson et al., 2017). The creation of these measures allows researchers and practitioners to understand how mindfulness changes with interventions. Moreover, specific measures have been created to study distinct mindfulness techniques such as self-compassion (e.g., Neff et al., 2021) and mindful eating (Hart et al., 2018). Hence, these measures can help further understand the mechanisms of change in mindfulness and are an important aspect in MBI research. However, little is known whether they are being used in MBI research, particularly with youth in schools. Previous systematic reviews have reported evidence of the effects of MBIs (i.e., Felver et al., 2016) and implementation fidelity (i.e., Gould et al., 2016) and integrity (i.e., Emerson et al., 2020); nonetheless these reviews are several years old, or do not include a comprehensive picture of some of the mindfulness techniques or active ingredients of the MBIs. Given the current gaps in the literature, a systematic review investigating techniques used in MBIs, the extent to which implementation fidelity is investigated, and what measures of mindfulness are used in MBI studies with youth.

Purpose of the Current Study

Although several studies have reviewed the outcomes and effects of MBIs in schools, none have detailed the mindfulness techniques being used in MBIs or other information regarding implementation. This information would help practitioners and researchers further understand critical components of MBIs implementation. Additionally, no study has systematically reviewed the fidelity of MBI implementation in schools or documented the mindfulness measures used in these studies. In order to do so, the current study will replicate and extend the work conducted by DE-IDENTIFIED by focusing on the following questions:

-

1.

What percentage of articles published in nine school psychology journals from 2006 to 2020 were related to mindfulness?

-

2.

What percentage of articles focused on the implementation of mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) with students in schools?

-

3.

What mindfulness techniques (e.g., deep breathing, body scan, visualization) are included in school-based MBIs?

-

4.

How is fidelity of MBI implementation measured?

-

5.

How are mindfulness skills measured for students in school-based MBIs?

Method

A systematic literature search was conducted on nine peer-reviewed school psychology journals (School Psychology Review, School Psychology Forum, Journal of School Psychology, Journal of Applied School Psychology, School Psychology Quarterly, International Journal of School and Educational Psychology, Contemporary School Psychology, Psychology in Schools, and School Psychology International) from 2006 to 2020. These journals were selected because they had the terms “school” and “psychology” in the title, have recognition and impact in the field, and are recognized by national or international professional organizations in school psychology. These journals were also selected because they were found to be the most common publication outlets for school psychology faculty (Hulac et al., 2016). This method and rationale of journal selection is consistent with previous research that has conducted similar reviews (DE-IDENTIFIED, 2018; Hendricker et al., 2018). The first and third author reviewed articles related to mindfulness utilizing the following key words in the title, abstract or keywords: mindful, mindfulness, meditation, yoga, aware, awareness, breath, breathe, breathing, and self-regulation. Commentaries and introductions to special issues were excluded. This initial round yielded a total of 156 articles that were recorded utilizing Microsoft Office Excel, with an inter-rater reliability of 99%.

The next phase consisted of reviewing the 156 articles to include only articles that directly addressed mindfulness as the main topic. Articles that mentioned regulation in their titles, abstract or keywords but studied a different variable were excluded. For example, Chong (2007) studied beliefs that mediated self-regulation skills. While it could be argued that self-regulation may be a component of mindfulness, the object and theoretical framework of this study did not include mindfulness, therefore it was excluded. Additionally, although social-emotional learning (SEL) programming in schools is commonly implemented and there is conceptual and practical overlap of mindfulness and SEL (Feuerborn & Gueldner, 2019), articles examining SEL programs that did not directly discuss mindfulness as part of their programming were excluded. The first and third author used the mentioned table to track decisions, finally yielding a total of 46 articles with an inter-rater reliability of 100%.

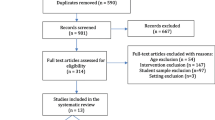

The third phase consisted of examining articles to determine if they were empirical in nature and focused on the implementation of an MBI in schools for students. MBIs implemented any tier (i.e., tier 1, 2, or 3) were included. Interventions that were directed towards teachers and other adults were excluded (n = 5). This phase yielded a total of 23 articles, to which the first and third author extracted the information required to answer the research questions. A flowchart (see Fig. 1) was prepared to illustrate the different phases of the review, as well as the inclusion and exclusion criteria for each phase. Systematic review guidelines set forth by PRISMA (Page et al., 2021) was followed to improve the quality of methodology and reporting of findings. See Fig. 1 for the current study’s PRISMA flowchart.

In order to quantify the techniques implemented within MBIs, a frequency count of techniques were calculated and categories created. First, various mindfulness techniques reported in MBIs were reviewed. Second, MBI technique categories were created based on the description provided by authors and similitude among the different studies. Finally, the yielded categories were compared to the current literature for accuracy. The nine categories were as follows:

-

1)

Breathing: any technique that has the breath as a core component. Techniques mentioned in articles that included the word “breath” or “breathing” were coded in this category.

-

2)

Body scan or body sweep: involves systematic “sweeping” of each part of the body, starting from the toes and moving up to the head (Anālayo, 2020).

-

3)

Awareness: includes awareness of body, sensation, emotions, thoughts, mindful movement, sound practice.

-

4)

Heartfulness: includes practices such as compassion, kindness, gratitude, reducing self-judgment; involves the “warmer” mindfulness techniques related to the “heart” (Voci et al., 2019)

-

5)

Yoga: “a discipline that integrates techniques harnessing the mind and body in relief of stress, relaxation, and transcendence from the material” (Taneja, 2014).

-

6)

Mandala Coloring: “colouring in the intricate shapes and patterns [of mandalas] allows students to experience a focused and aware state inherent to mindfulness” (Carsley & Heath, 2018, p.255).

-

7)

Meditation: includes sitting meditation, mindful meditation, centering meditation. It is defined as “a practice in which an individual trains their mind or induces a mode of consciousness to allow the mind to involve within peaceful thoughts” (Santhanam et al., 2018).

-

8)

Visualization: refers to the “practice of conscious control of mental imagery” (Margolin et al., 2011, p. 241). In other words, control of perceptual information that comes from imagination rather than physical stimuli.

-

9)

Other: any technique that did not fall into the above-mentioned categories (e.g., discussion of topics related to the context).

Results

Research Question 1: What Percentage of Articles Published in Nine School Psychology Journals from 2006 to 2020 Were Related to Mindfulness?

The current study found a total of 46 mindfulness articles published in school psychology journals between 2006 and 2020, out of 4415 (1.09%) (Fig. 2). An increasing number of articles were published over the years with the fewest being published in 2010 (n = 1), increased in 2013 (n = 2), remained stable until 2015, and then in 2016 (n = 9) and 2017 (n = 14), a larger increase occurred. A decline was observed in 2018 (n = 9), 2019 (n = 5), and 2020 (n = 5). No articles related to mindfulness were found in years 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, or 2011 (Fig. 2).

Research Question 2: What Percentage of Articles Focused on the Implementation of MBIs?

Of the 46 articles, 23 focused on implementing an MBI in schools for students (50%). Similar to the overall mindfulness publication trend described above, mindfulness-based intervention articles increased from 2010 (n = 1), increased in 2014 (n = 2), remained stable until 2016, and then in 2017 (n = 9) a larger increase occurred. A decline was observed in 2018 (n = 5), and 2019 (n = 1). No articles related to mindfulness-based interventions were found in years 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2011, 2013, or 2022 (Fig. 2).

Research Question 3: What Techniques (e.g., Deep Breathing, Body Scan, Visualization) in MBIs Are Most Commonly Taught to Students?

All techniques described in MBIs were examined, coded into categories (i.e., breathing, body scan or body sweep, awareness, heartfulness, yoga, mandala colouring, meditation, visualization, other) and were listed and counted for frequency (see Fig. 3). Awareness was the most taught technique to students with 21 (out of 23) studies referencing this technique in their MBI. Another frequent technique included in school-based MBIs was breathing (n = 12), meditation (n = 8), yoga (n = 7), and body scan or body sweep (n = 7). Heartfulness (n = 4), mandala coloring (n = 2), visualization (n = 2), and other (n = 1) were included less frequently.

Research Question 4: How Is Fidelity of MBI Implementation Measured?

Out of the 23 studies, 9 (39.1%) articles reported fidelity in their MBI implementation procedures (Table 1). Of these studies, six studies utilized a self-report implementation checklist (completed by facilitators/teachers), four used direct observation completed by an observer (e.g., researchers), and two studies employed both methods. Direct observations were conducted using an implementation checklist with items retrieved from the intervention steps presented in manuals and/or intervention plan.

Research Question 5: How Are Mindfulness Skills Measured for Students?

Five out of 23 studies (21.7%) utilized a mindfulness scale to measure mindfulness skill change for students (Table 1). Mindfulness was measured by self-report on the Cognitive and Affective Mindfulness Scale-Revised (CAMS-R), Mindful Attention Awareness Scale for Children (MAAS-C), or Mindful Student Questionnaire (MSQ). Of the five studies that measured mindfulness directly, two studies reported significant changes in mindfulness skills post intervention including. For instkance, Devcich et al. (2017)found that students reported increased levels of mindfulness as measured by the MAAS-C, which was positively correlated with subjective well-being. Furthermore, Carsley and Health (2018) found that their participants reported increased states mindfulness and decreased test anxiety, with baseline scores mediating post treatment measures.

Discussion

Mindfulness interventions in schools have become increasingly implemented for youth in educational contexts (Klingbeil et al., 2017). MBI outcome research has been most prevalent, with less understanding of what specific mindfulness techniques are being used in MBIs in schools, how fidelity is being measured, and if mindfulness skills are evaluated within studies. Given its current relevance in the field and in research, it is important to advance the understanding of mindfulness as a variable of change in the school community.

The present study systematically reviewed nine school psychology journals from 2006 to 2020 to examine the prevalence of current mindfulness research and investigate characteristics of MBIs. In the current review, there was noticeable increase of mindfulness research in the literature since 2016 (see Fig. 2). In a previous study conducted by DE-IDENTIFIED (2018), researchers found 17 articles related to mindfulness and of those 17, eight that consisted of MBI implementation across school psychology journals. The current study found a growth of 29 MBI articles since the publication of that previous study. This indicates that since 2016 there has been a 3.3 increase of empirical studies published. This increase follows the trend observed in other reviews conducted using a wider range of journals (Dunning et al., 2019; Klingbeil et al., 2017). It is important to note that there is a sharp decrease in 2020, which may be due to several factors. First, nationwide school closures due to COVID-19 occurred early in 2020, with instruction and any other supports provided for students going remote and/or online. It could be the case that in-person MBI intervention research may have been discontinued. Additionally, given the impacts of multiple pandemics, racism and COVID-19, there has been a necessary (and overdue) urgency for research related to anti-racism, social justice, and COVID-19. Finally, as the state of literature advances toward more complex research designs, it could be possible that newer projects require longer time, funding, and revisions before they get published.

Gaps in the literature indicate that MBIs are yielding positive effects for participants; however, little is known about core components that constitute the mindfulness practices. This review intended to better understand the various core components used in MBIs in schools by recording each techniques frequency use and categorizing them, according to the literature. Although mindfulness has a fairly agreed upon definition that involves the self-regulation of attention to increase awareness of the present moment with an open attitude (Bishop et al., 2004), there are varying practices of to allow one to practice engagement with mindfulness. For example, Renshaw (2020) proposes two behavioral components of Mindfulness. The first one is present moment awareness (PMA), which involves “orientating one’s attention to the here and now” (p. 146). This component could align well with mindfulness techniques categories such as awareness, body scan, yoga, breathing, and meditation. The second component is responding with acceptance (RWA), which “refers to the quality of one’s reactions to the contents of PMA” (p. 146); this reaction is one of curiosity and persistence, which is reflected in the heartfulness techniques of mindfulness.

On the other hand, Crane et al., (2017) conceptualized MBIs as a practice that “supports the development of greater attentional, emotional and behavioral self-regulation, as well as positive qualities such as compassion, wisdom, equanimity” (p. 994) with three core techniques: body scan, mindful movement and sitting meditation. While the proposed categories expand the work of Crane et al., (2017), in the current study, we found seven MBIs used body scan, eight MBIs used a form of meditation (including sitting meditation), and mindful movement was coded in the awareness category. Crane et al., (2017) also included the development of recognition of experiences, which may interpret as a process of awareness.

In terms of the specific types of mindfulness skills taught in MBI studies reviewed, awareness, breathing, meditation, yoga, and body scan or body sweeps were the most taught techniques among the intervention studies. Using the literature as a guide, MBI techniques listed and described in the 23 reviewed articles were analyzed and coded. These categories aided the process of understanding the techniques that are being included and studied in the MBIs in school research. This is not surprising given that yoga and breathing techniques are ancient western practices that have been around over 2000 years. Mindfulness, an eastern invention, is inspired by some of the Buddhist elements to form its practical basis (Shapiro et al., 2006). Therefore, yoga, breathing, and mediation are the first techniques that became popular, hence, studied (e.g., Bray et al., 2012; Felver et al., 2015).

It is reassuring that 21 studies used a form of awareness (emotions, thoughts, present moment, body awareness, sensations) within their MBIs. Mindfulness is commonly described as the awareness of the present moment as it is (Kabat-Zinn, 1994). Therefore, it is not surprising that many MBI interventions included the practice of becoming aware of thoughts, emotions, and/or sensations. Some studies (e.g., Britton et al., 2014; Kang et al., 2018) used several awareness activities (such as awareness of sensations, thoughts, and emotions); others (e.g., Felver et al., 2017; Long et al., 2018) focused on only one form (such as body awareness, which is very close to yoga). Overall, awareness of sensations was the most common technique used in this category (n = 7), whereas awareness of the present moment was the least one used (n = 1).

Shapiro et al. (2006) defined mindfulness practice as one that involves a “heartful” attitude towards life that involves compassion and kindness, requires a specific intention when one practices mindfulness, as well as a regulation of the attention. In the current study, four studies included a form of heartfulness techniques in their intervention. For example, Wood et al. (2018) included a compassion practice as part of their intervention program, supporting executive function in preschoolers. Another example comes from Felver et al. (2019) who worked with harmful self-judgement in teenagers among other mindfulness techniques to improve resiliency in teenagers. These studies are similar to previous research that included self-compassion and other heartful techniques to support youth’s wellbeing (e.g., Bluth et al., 2015; Bluth & Eisenlohr-Moul, 2017).

Compassionate and kindness interventions may increase self-compassion, but not make a significant impact on awareness (Hildebrandt et al., 2017). Others have noted mindfulness techniques may be mediated by different variables. For instance, MBSR may be mediated by awareness, whereas compassion training may be mediated by emotional mechanisms (Roca et al., 2021). This suggests that while mindfulness techniques can improve well-being, the mechanism is not equal. Therefore, MBIs may not be developed under the same mechanism but there is a dearth of research in understanding these differences when applied to schools.

Consistent with the theoretical framework that mindfulness is comprised of several techniques (Crane et al., 2017), the review found that 66% of the reviewed articles included two or more mindfulness techniques in their intervention protocol. This means that the MBI programs of the reviewed articles are comprised of several mindfulness techniques, such as Learning to Breath, which is comprised of awareness, meditation and heartfulness techniques (Felver et al., 2019). From the categorized techniques, there seems to be a pattern of interventions using a cocktail of techniques that targets the components mentioned by Crane et al. (2017) and Renshaw (2020).

In terms of implementation fidelity rates, only 39.1% of the studies reported fidelity results as part of their protocol. While this study did not follow Gould et al. (2016) methodology to assess implementation fidelity, the intervention studies that did include evaluation of fidelity provided evidence that their studies included a comprehensive measure of fidelity. These comprehensive measures included implementation checklists and direct observations. These were completed by facilitators (i.e., teachers, interventionists, researchers), and the measures used the intervention manuals of the study to quantify adherence. This indicates that the studies that included evaluation of fidelity had distinct, specific, and measurables steps to complete the intervention.

Finally, the present study reviewed whether mindfulness scales, used to assess direct changes in mindfulness, were included in mindfulness intervention studies. Only 21.7% of the studies examined used a mindfulness measure, such as the Cognitive and Affective Mindfulness Scale Revised (CAMS-R), Mindful Attention Awareness Scale for Children (MAAS-C), and Mindful Student Questionnaire (MSQ). While this is an encouraging start, there is still a lack of clarity about how these measures are being used and lack of overall MBI studies utilizing measures of mindfulness. This finding of 21.7% in the current study is lower than a study conducted by Carsley et al. (2018) who found that 41.6% of their studies reviewed used a mindfulness scale. This discrepancy may be due to different methodology. For instance, Carsley et al. (2018) reviewed youth programs throughout all journals.

Future Directions

Future research should aim to understand the various techniques used in MBIs, further evaluation of MBI implementation fidelity, and use of mindfulness measures to examine the effects of the different techniques on youth’s mindfulness skills. For that to happen, researchers should further the validation of mindfulness as a construct using mindfulness scales (e.g., Farley et al., 2022), while also increasing intervention research that incorporates implementation science elements such as implementation fidelity (e.g., Karing & Beelmann, 2021).

It is important for practitioners and researchers to measure and evaluate skills that are being particularly targeted in intervention to make decisions and evaluate the impact of the techniques. In social-emotional learning programs for example, skills that are practiced or targeted in the intervention (e.g., self-awareness, sharing, regulating emotions) are also being measured to determine if the intervention has an effect on these behaviors. The same should hold true for MBIs. If MBIs are intended to target mindfulness skills, which are hypothesized to lead to positive outcomes for students (e.g., improved executive function skills, reduced anxiety), then understanding what mindfulness skills have improved is important. As Renshaw and Cook (2017) report, it is important for research to dismantle studies and understand the supposed active ingredients in MBIs. The current systematic review attempted to begin this dismantling by examining the type, range, and frequency of techniques are used in school-based MBIs.

As this review illustrated, studies are just beginning to take into consideration fidelity as an element of MBI implementation in schools. However, as discussed by Emerson et al. (2020) and Zenner et al. (2014), who found very few studies with implementation integrity in their review, MBIs in school research still requires a lot of attention in regard to this. This is consistent with the broader literature of Social Emotional Learning interventions (SEL; Bruhn et al., 2015; Green et al., 2021; Wanless & Domitrovich, 2015), in which implementation fidelity is being monitored by checklists being completed by the implementer. Nonetheless, it is important to note that SEL interventions across tiers are often time including a multi-method, multi-informant approach (Bruhn et al., 2015).

Less than a quarter of the studies examined used a mindfulness measure for youth to report their mindfulness skills. This lack of clarity of how these measures are used, the benefit and/or drawbacks of using them, and how it may improve an understanding of mechanisms of change in MBIs is needed in the field. The use of mindfulness measures may help practitioners and researchers examine the effects of the different techniques on youth’s mindfulness skills and these elements could help researchers discern what is the underlying mechanisms that supports the benefits of MBIs in youth.

Limitations

There are limitations to acknowledge in this systematic review. First, is the limited range of journals included. Mindfulness is being studied by several fields, with their findings being published in journals such as Mindfulness. These findings are restricted to articles that were published in school psychology journals. While this comes with the advantage of having a better understanding of what is being published in the school psychology field, it also limits the scope of articles and information. In addition, the categorization process was “rudimentary”, using the authors’ knowledge and interpretation of the researcher’s intervention plan. Furthermore, the categories may create opportunities for overlapping techniques (e.g., Breathing meditation or Breath Awareness) that can overestimate the number of categories or frequency of times a technique is used. While there were potential limitations of the proposed categories, this was an attempt at a first step in understanding what techniques are included in MBIs in schools and helps to improve understanding of the commonalities of techniques used in these programs.

References

Abujaradeh, H., Colaianne, B. A., Roeser, R. W., Tsukayama, E., & Galla, B. M. (2020). Evaluating a short-form Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire in adolescents: Evidence for a four-factor structure and invariance by time, age, and gender. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 44(1), 20–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025419873039

Anālayo, B. (2020). Buddhist antecedents to the body scan meditation. Mindfulness, 11(1), 194–202. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-019-01259-8

Bannirchelvam, B., Bell, K. L., & Costello, S. (2017). A qualitative exploration of primary school students’ experience and utilisation of mindfulness. Contemporary School Psychology, 21(4), 304–316. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-017-0141-2

Bishop, S. R., Lau, M., Shapiro, S., Carlson, L., Anderson, N. D., Carmody, J., Segal, Z. V., Abbey, S., Speca, M., Velting, D., & Devins, G. (2004). Mindfulness: A proposed operational definition. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 11(3), 230–241. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy.bph077

Black, D. S., Milam, J., & Sussman, S. (2009). Sitting-meditation interventions among youth: A review of treatment efficacy. Pediatrics, 124, e532–e541. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2008-3434

Bray, M.A., Sassu, K.A., Kapoor, V., Margiano, S., Peck, H.L., Kehle, T.J., & Bertuglia, R. (2012). Yoga as an intervention for asthma. School Psychology Forum, 6(2), 39–49. Retrieved from https://www.nasponline.org/publications/periodicals/spf/volume-6/volume-6-issue-2-(summer-2012)/yoga-as-an-intervention-for-asthma

Briere, J. (2011). Mindfulness inventory for children and adolescents. Unpublished assessment inventory. University of Southern California. Los Angeles, CA.

Britton, W. B., Lepp, N. E., Niles, H. F., Rocha, T., Fisher, N. E., & Gold, J. S. (2014). A randomized controlled pilot trial of classroom-based mindfulness meditation compared to an active control condition in sixth-grade children. Journal of School Psychology, 52(3), 263–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2014.03.002

Bruhn, A. L., Hirsch, S. E., & Lloyd, J. W. (2015). Treatment Integrity in School-Wide Programs: A Review of the Literature (1993–2012). The Journal of Primary Prevention, 36(5), 335–349. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10935-015-0400-9

Burke, C. A. (2010). Mindfulness-based approaches with children and adolescents: A preliminary review of current research in an emergent field. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 19, 133–144. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-009-9282-x

Carsley, D., & Heath, N. L. (2018). Effectiveness of mindfulness-based colouring for test anxiety in adolescents. School Psychology International, 39(3), 251–272. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034318773523

Carsley, D., Heath, N. L., & Fajnerova, S. (2015). Effectiveness of a classroom mindfulness coloring activity for test anxiety in children. Journal of Applied School Psychology, 31(3), 239–255. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034318773523

Carsley, D., Khoury, B., & Heath, N. L. (2018). Effectiveness of mindfulness interventions for mental health in schools: A comprehensive meta-analysis. Mindfulness, 9(3), 693–707. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-017-0839-2

Crane, R. S., Brewer, J., Feldman, C., Kabat-Zinn, J., Santorelli, S., Williams, J. M. G., & Kuyken, W. (2017). What defines mindfulness-based programs? The warp and the weft. Psychological Medicine, 47(6), 990–999. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291716003317

Dariotis, J. K., Mirabal-Beltran, R., Cluxton-Keller, F., Feagans Gould, L., Greenberg, M. T., & Mendelson, T. (2017). A qualitative exploration of implementation factors in a school-based mindfulness and yoga program: Lessons learned from students and teachers. Psychology in the Schools, 54(1), 53–69. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.21979

Bender, S. L., Roth, R., Zielenski, A., Longo, Z., & Chermak, A. (2018). Prevalence of mindfulness literature and intervention in school psychology journals from 2006 to 2016. Psychology in the Schools, 55(6), 680–692. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22132

Devcich, D. A., Rix, G., Bernay, R., & Graham, E. (2017). Effectiveness of a mindfulness-based program on school children’s self-reported well-being: A pilot study comparing effects with an emotional literacy program. Journal of Applied School Psychology, 33(4), 309–330. https://doi.org/10.1080/15377903.2017.1316333

Dunning, D. L., Griffiths, K., Kuyken, W., Crane, C., Foulkes, L., Parker, J., & Dalgleish, T. (2019). Research review: The effects of mindfulness-based interventions on cognition and mental health in children and adolescents meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 60(3), 244–258. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12980

ElGarhy, S., & Liu, T. (2016). Effects of psychomotor intervention program on students with autism spectrum disorder. School Psychology Quarterly, 31(4), 491–506. https://doi.org/10.1037/spq0000164

Emerson, L. M., de Diaz, N. N., Sherwood, A., Waters, A., & Farrell, L. (2020). Mindfulness interventions in schools: Integrity and feasibility of implementation. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 44(1), 62–75. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025419866906

Farley, C., Renshaw, T., Franzmann, K., & Phan, M. (2022). Validating Multiple Mindfulness Measures [Conference Presentation]. Boston, MA, United States: NASP 2022 Convention.

Felver, J. C., Butzer, B., Olson, K. J., Smith, I. M., & Khalsa, S. B. S. (2015). Yoga in public school improves adolescent mood and affect. Contemporary School Psychology, 19(3), 184–192. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-014-0031-9

Felver, J. C., Celis-de Hoyos, C. E., Tezanos, K., & Singh, N. N. (2016). A Systematic Review of Mindfulness-Based Interventions for Youth in School Settings. Mindfulness, 7(1), 34–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-015-0389-4

Felver, J. C., Clawson, A. J., Morton, M. L., Brier-Kennedy, E., Janack, P., & DiFlorio, R. A. (2019). School-based mindfulness intervention supports adolescent resiliency: A randomized controlled pilot study. International Journal of School & Educational Psychology, 7(sup1), 111–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/21683603.2018.1461722

Felver, J. C., Felver, S. L., Margolis, K. L., Ravitch, N. K., Romer, N., & Horner, R. H. (2017). Effectiveness and social validity of the soles of the feet mindfulness-based intervention with special education students. Contemporary School Psychology, 21(4), 358–368. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-017-0133-2

Feuerborn, L. L., & Gueldner, B. (2019). Mindfulness and social-emotional competencies: Proposing connections through a review of research. Mindfulness, 10, 1707–1720. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-019-01101-1

Flook, L., Smalley, S. L., Kitil, M. J., Galla, B. M., Kaiser-Greenland, S., Locke, J., Ishijima, E., & Kasari, C. (2010). Effects of mindful awareness practices on executive functions in elementary school children. Journal of Applied School Psychology, 26(1), 70–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/15377900903379125

Frank, J. L., Bose, B., & Schrobenhauser-Clonan, A. (2014). Effectiveness of a school-based yoga program on adolescent mental health, stress coping strategies, and attitudes toward violence: Findings from a high-risk sample. Journal of Applied School Psychology, 30(1), 29–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/15377903.2013.863259

Garner, P. W., Bender, S. L., & Fedor, M. (2018). Mindfulness-based SEL programming to increase preservice teachers’ mindfulness and emotional competence. Psychology in the Schools, 55(4), 377–390. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22114

Gould, L. F., Dariotis, J. K., Greenberg, M. T., & Mendelson, T. (2016). Assessing fidelity of implementation (FOI) for school-based mindfulness and yoga interventions: A systematic review. Mindfulness, 7(1), 5–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-015-0395-6

Greco, L. A., Baer, R. A., & Smith, G. T. (2011). Assessing mindfulness in children and adolescents: Development and validation of the Child and Adolescent Mindfulness Measure (CAMM). Psychological Assessment, 23(3), 606–614. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022819

Green, A. L., Ferrante, S., Boaz, T. L., Kutash, K., & Wheeldon‐Reece, B. (2021). Social and emotional learning during early adolescence: Effectiveness of a classroom‐based SEL program for middle school students. Psychology in the Schools, 58(6), 1056–1069. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22487

Hart, S. R., Pierson, S., Goto, K., & Giampaoli, J. (2018). Development and initial validation evidence for a mindful eating questionnaire for children. Appetite, 129, 178–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2018.07.010

Hendricker, E., Bender, S. L., & Ouye, J. (2018). Family involvement in school-based behavioral screening: A review of six school psychology journals from 2004 to 2014. Contemporary School Psychology, 22, 344–354. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-017-0163-9

Hildebrandt, L. K., McCall, C., & Singer, T. (2017). Differential effects of attention-, compassion-, and socio-cognitively based mental practices on self-reports of mindfulness and compassion. Mindfulness, 8(6), 1488–1512. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-017-0716-z

Hulac, D., Johnson, N. D., Ushijima, S. C., & Schneider, M. M. (2016). Publication outlets for school psychology faculty: 2010 to 2015. Psychology in the Schools, 53(10), 1085–1093. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.21977

Idler, A. M., Mercer, S. H., Starosta, L., & Bartfai, J. M. (2017). Effects of a mindful breathing exercise during reading fluency intervention for students with attentional difficulties. Contemporary School Psychology, 21(4), 323–334. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-017-0132-3

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1990). Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain and illness. New York, NY: Delacorte.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1994). Wherever you go, there you are: Mindfulness meditation in everyday life. Hyperion.

Kang, Y., Rahrig, H., Eichel, K., Niles, H. F., Rocha, T., Lepp, N. E., Gold, J., & Britton, W. B. (2018). Gender differences in response to a school-based mindfulness training intervention for early adolescents. Journal of School Psychology, 68, 163–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2018.03.004

Khoury, B., Sharma, M., Rush, S. E., & Fournier, C. (2015). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for healthy individuals: A meta-analysis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 78(6), 519–528. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2015.03.009

Kielty, M., Gilligan, T., Staton, R., & Curtis, N. (2017). Cultivating Mindfulness with third grade students via classroom-based interventions. Contemporary School Psychology, 21(4), 317–322. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-017-0149-7

Klingbeil, D. A., Renshaw, T. L., Willenbrink, J. B., Copek, R. A., Chan, K. T., Haddock, A., Yassine, J., & Clifton, J. (2017). Mindfulness-based interventions with youth: A comprehensive meta-analysis of group-design studies. Journal of School Psychology, 63, 77–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2017.03.006

Kurth, L., Engelniederhammer, A., Sasse, H., & Papastefanou, G. (2020). Effects of a short mindful-breathing intervention on the psychophysiological stress reactions of German elementary school children. School Psychology International, 41(3), 218–238. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034320903480

Long, A. C., Renshaw, T. L., & Camarota, D. (2018). Classroom management in an urban, alternative school: A comparison of mindfulness and behavioral approaches. Contemporary School Psychology, 22(3), 233–248. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-018-0177-y

Luiselli, J. K., Worthen, D., Carbonell, L., & Queen, A. H. (2017). Social validity assessment of mindfulness education and practices among high school students. Journal of Applied School Psychology, 33(2), 124–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-016-0664-z

Margolin, I., Pierce, J., & Wiley, A. (2011). Wellness Through a Creative Lens: Mediation and Visualization. Journal of Religion & Spirituality in Social Work: Social Thought, 30(3), 234–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/15426432.2011.587385

Matsuba, M. K., & Williams, L. (2020). Mindfulness and yoga self-care workshop for Northern Ugandan teachers: A pilot study. School Psychology International, 41(4), 351–367. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034320915955

Milligan, K., Cosme, R., Miscio, M. W., Mintz, L., Hamilton, L., Cox, M., Woon, S., Gage, M., & Phillips, M. (2017). Integrating mindfulness into mixed martial arts training to enhance academic, social, and emotional outcomes for at-risk high school students: A qualitative exploration. Contemporary School Psychology, 21(4), 335–346. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-017-0142-1

Napoli, M., Krech, P. R., & Holley, L. C. (2005). Mindfulness training for elementary students: The Attention Academy. Journal of Applied School Psychology, 21(1), 99–125. https://doi.org/10.1300/J370v21n01_05

Neff, K. D., Bluth, K., Tóth-Király, I., Davidson, O., Knox, M. C., Williamson, Z., & Costigan, A. (2021). Development and validation of the Self-Compassion Scale for Youth. Journal of Personality Assessment, 103(1), 92–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2020.1729774

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 10(1), 89. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01626-4

Renshaw, T. L., & Cook, C. R. (2017). Introduction to the special issue: Mindfulness in the schools—Historical roots, current status, and future directions. Psychology in the Schools, 54(1), 5–12. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.21978

Renshaw, T. L., Fischer, A. J., & Klingbeil, D. A. (2017). Mindfulness-based intervention in school psychology. Contemporary School Psychology, 21, 299–303. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-017-0166-6

Renshaw, T. L. (2020). Mindfulness-based intervention in schools. In C. Maykel & M. A. Bray (Eds.), Promoting mind–body health in schools: Interventions for mental health professionals (pp. 145–160). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000157-010

Roca, P., Vazquez, C., Diez, G., Brito-Pons, G., & McNally, R. J. (2021). Not all types of meditation are the same: Mediators of change in mindfulness and compassion meditation interventions. Journal of Affective Disorders, 283, 354–362. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.01.070

Rosenzweig, D. (2013). The Sisters of Mindfulness. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 69(8), 793–804. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22015

Rush, K. S., Golden, M. E., Mortenson, B. P., Albohn, D., & Horger, M. (2017). The effects of a mindfulness and biofeedback program on the on- and off-task behaviors of students with emotional behavioral disorders. Contemporary School Psychology, 21(4), 347–357. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-017-0140-3

Santhanam, P., Preetha, S., & Devi, R. G. (2018). Role of meditation in reducing stress. Drug Invention Today, 10(11).

Segal, Z. V., Williams, J. M. G., & Teasdale, J. D. (2002). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression: A new approach to relapse prevention. Guilford.

Shapiro, S. L., Carlson, L. E., Astin, J. A., & Freedman, B. (2006). Mechanisms of mindfulness. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62(3), 373–386. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20237

Sun, J. (2014). Mindfulness in context: A historical discourse analysis. Contemporary Buddhism, 15(2), 394–415. https://doi.org/10.1080/14639947.2014.978088

Taneja, D. K. (2014). Yoga and health. Indian Journal of Community Medicine, 39(2), 68–72. https://doi.org/10.4103/0970-0218.132716

Terjestam, Y., Bengtsson, H., & Jansson, A. (2016). Cultivating awareness at school: Effects on effortful control, peer relations and well-being at school in grades 5,7, and 8. School Psychology International, 37(5), 456–469. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034316658321

Thompson, M., & Gauntlett-Gilbert, J. (2008). Mindfulness with children and adolescents: Effective clinical application. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 13(3), 395–407. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104508090603

Voci, A., Veneziani, C. A., & Fuochi, G. (2019). Relating mindfulness, heartfulness, and psychological well-being: The role of self-compassion and gratitude. Mindfulness, 10, 339–351. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-018-0978-0

Wanless, S. B., & Domitrovich, C. E. (2015). Readiness to Implement School-Based Social-Emotional Learning Interventions: Using Research on Factors Related to Implementation to Maximize Quality. Prevention Science, 16(8), 1037–1043.

Wood, L., Roach, A. T., Kearney, M. A., & Zabek, F. (2018). Enhancing executive function skills in preschoolers through a mindfulness-based intervention: A randomized, controlled pilot study. Psychology in the Schools, 55(6), 644–660. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22136

Zenner, C., Herrnleben-Kurz, S., & Walach, H. (2014). Mindfulness-based interventions in schools: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00603

Acknowledgements

We thank Rachel A. Gardner, Ph.D for important contribution in the methodology procedures

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Palacios, A.M., Bender, S.L. & Berry, D.J. Characteristics of Mindfulness-Based Interventions in Schools: a Systematic Review in School Psychology Journals. Contemp School Psychol 27, 182–197 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-022-00432-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-022-00432-6