Abstract

Sleep disturbance has emerged as a significant factor in the development and course of psychopathology. Its cross-cutting nature, demonstrated impact on co-occurring disorders, and the presence of efficacious interventions to address it, make sleep a desirable treatment target among individuals suffering from various mental and physical health disorders. In the past several years, researchers and clinicians alike have come to appreciate the role that sleep disturbance plays in the development and course of suicidal thought and behavior. The present review synthesizes the sleep and suicide literature published since 2012. A search of the PubMed and psycINFO databases yielded 41 articles that were appropriate for the present review. Consistent with prior reviews, sleep disturbance, insomnia, and nightmares were, overall, positively associated with suicidal thought and behavior. Future studies should seek to expand current lines of research in the sleep and suicide arena beyond global constructs and into investigations of mechanism.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As the tenth leading cause of death in the USA, suicide remains a pressing public health concern [1]. The increasing severity of the suicide problem was underscored in a recent National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) data brief which reported that the adjusted, national suicide rate rose 24 % between 1999 and 2014 [2]. During this time, sleep has emerged as a critical factor in the development, course, and resolution of conditions like depression and post-traumatic stress disorder [3–5]. Reports of a link between sleep and suicidal thoughts and behavior have also been available for some time [6], although the first meta-analysis examining the strength of this relationship was not published until 2012 [7]. A somewhat sizable body of work in this area has since been published.

As proposed by others [8, 9], the relationship between sleep and suicide may become manifest via numerous putative mechanisms. These include but are not limited to the following: a) fragmentation of the sleep cycle (e.g., difficulty falling asleep resulting in decreased total sleep time), b) disruption of neurotransmitters and hormones associated with the sleep-wake processes and with psychopathology, c) psychological distress or increased feelings of hopelessness, d) sleep disturbance blunted response to treatments aimed at reducing psychopathology, e) impaired executive functioning, and f) increased prevalence of medical comorbidities.

Until recently, the literature regarding the sleep-suicide relationship has remained largely at the construct and conceptual level. Similarly, investigations of the relationships among sleep variables and suicidal thought and behavior most often occurred at the level of generalized “sleep disturbance.” Finally, given the existence of several efficacious treatments for common sleep disorders (e.g., insomnia, sleep apnea, nightmares) [10], sleep disturbance represents a highly modifiable risk factor for suicide. In order for sleep medicine to augment suicide prevention strategies, however, it is important to solidify our understanding of the relationships of sleep variables to suicide outcomes and particularly whether sleep disturbance is an independent risk factor for suicide or simply a proxy for psychopathology like depression. To that end, publications have increasingly examined the relationship of specific disorders (e.g., insomnia) in the development and course of suicidal thought and behavior, while controlling for psychopathology. The present review synthesizes the literature on this topic published since 2012 and reports on the unique associations that insomnia, nightmares, and generalized sleep disturbance each have with suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and suicide.

Methods

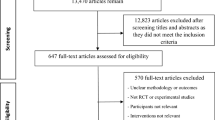

A systematic review of the literature was conducted using both PsycINFO and PubMed databases. Using Boolean search logic and MeSH terms, the search was driven using the following terms: suicide or suicidal or suicide attempt or suicidal thought or suicidal ideation and sleep or sleep disturbance or sleep disorder or nightmare or dream or insomnia or shift work or shiftwork or sleep apnea or sleep disordered breathing or sleep initiation disorder or sleep maintenance disorder or sleep psychology or sleep epidemiology. In order to supplement the literature search, a hand search was conducted using the references sections of the reviewed articles. Eligible articles met the following criteria : 1) available in English, 2) utilized human subjects over 18 years of age, 3) original research, 4) published in a peer reviewed journal, 5) reported data on suicidal ideation, attempts, or deaths, 6) reported data on sleep pathology, pattern, or quality, 7) the association between suicide and sleep outcomes were reported or presented in such a way that the relationship could be interpreted and were published between January 1, 2012 and January 1, 2016.

Results

The literature search resulted in 1003 articles from PubMed and 839 from PsycINFO databases. A total of 12 articles were also identified by hand-searching the reference sections of the reviewed articles. This sample of articles was then reduced by including only articles published between January 1, 2012 and January 1, 2016. Of the 96 articles remaining, 65 were identified as warranting further review. Seventeen articles were excluded because the relationship between sleep and suicide was not interpretable. Another seven articles were excluded because they were not considered original research (e.g., case studies, commentaries). This left a total of 41 articles that met all inclusion criteria (see Fig. 1).

The articles included in this review are primarily cross-sectional, examine a range of populations, and utilize a number of different sleep and suicide variables. For ease of interpretation, we have organized the review that follows into four main subsections: generalized sleep disturbance, insomnia, nightmares, and other sleep variables or conditions (e.g., articles that addressed sleep quality, sleep duration, circadian rhythms, or sleep apnea). Table 1 also lists articles by these section headings, where an article may appear in more than one section if it addressed more than one of these topics. Finally, given the high profile of suicide among military veterans, the text includes a section on the sleep-suicide relationship among this population (the section is not included in Table 1).

Generalized Sleep Disturbance

Ten studies included in this review [11–13, 14•, 15, 16, 17•, 18–20] provided a characterization of the relationship among generalized sleep disturbance (e.g., utilized sleep variables that did not measure a specifically defined construct such as insomnia) and suicidal thought and behavior. All ten of the studies examined reported an initial significant association between sleep disturbance and suicidality. Notably, of these studies, nine also examined this relationship while controlling for comorbid psychopathology and in all but one the relationship between suicidality and sleep disturbance remained significant [12]. Two studies conducted longitudinal examinations of the relationship between sleep disturbance and suicidality [11, 17•]. Nadorff and colleagues [17•] followed psychiatric inpatients (N = 1529) biweekly over the course of a 6-week treatment episode and found that changes in sleep patterns were associated with greater suicidal ideation at both admission and discharge. Further, for those participants whose sleep did not improve during the treatment episode, suicidal ideation was significantly greater at discharge. Pigeon and colleagues [11] conducted retrospective chart reviews on a sample of veteran suicide decedents (N = 424) who had a documented visit to the Veterans Health Administration in the year prior to their death. After adjusting for comorbid psychopathology and age, those veterans with sleep disturbance had a shorter time to death as compared to those veteran suicide decedents without sleep disturbance. It is of note that three of these studies reported significant associations among sleep disturbance and either suicide attempts [18] or death by suicide [11, 16], providing further evidence that the relationship between sleep and suicide is not limited to ideation, but rather extends to behavior.

Insomnia

Eighteen studies reported on the relationship between insomnia and suicidality [15, 21, 22, 23•, 24–28, 29•, 30•, 31, 32, 33•, 34–37]. Four of these investigations were longitudinal in nature [22, 23•, 29•, 30•], and each reported a positive relationship between insomnia and suicidality (suicidal ideation [22, 29•], suicide attempts [23•], or suicide [30•]). Of these four studies, only Suh and colleagues’ [29•] findings relating suicidal ideation to insomnia did not hold up after accounting for comorbid psychopathology. A few studies reported null findings regarding the relationship between insomnia and suicide risk [32] and suicide attempt [21, 28], with three additional studies having nonsignificant findings after controlling for comorbid psychopathology [34–36]. The majority of studies that examined insomnia, however, reported that a significant association with greater suicidality remained after accounting for co-occurring psychopathology [15, 22, 23•, 24, 25, 27, 30•, 31, 33•, 37].

Nightmares

Seven studies explored the relationship between nightmares and suicidal thought and behavior [22, 27, 32, 34, 36, 38, 39]. The examination of the relationship between nightmares and suicidality presents an interesting angle with which to explore the sleep-suicide relationship. Nightmares, however, are often observed in the context of comorbid psychopathology (e.g., posttraumatic stress disorder or a significant trauma history). This makes it ever more important that researchers attempt to disentangle the unique effects of the presence or severity of nightmares from co-occurring or comorbid disorders. Of the seven studies included in this review, six reported positive associations between the presence or severity of nightmares and suicidal thought or behavior [17•, 22, 27, 36, 38, 39]. Of those, four studies further examined these relationships while controlling for other psychopathology and all four results remained significant [17•, 22, 27, 36].

Other Sleep Variables and Conditions

Sleep Quality

Nine of ten studies that examined sleep quality reported a positive relationship between sleep quality and suicidality [30•, 38, 40, 41•, 42–46]. Of the eight studies in this group that examined suicidal ideation, five did so why controlling for psychopathology. Notably, all five of these studies reported a significant association between poorer sleep quality and presence of suicidal ideation that remained significant after controlling for comorbid psychopathology [42–46]. The lone study of sleep quality and suicidality that reported null findings involved a cross-sectional examination of outpatient, female, fibromyalgia patients [47].

Sleep Duration

Between the years of 2012 and 2016, five cross-sectional studies, including several large community studies, reported on the relationship between sleep duration and suicide [14•, 41•, 42, 48, 49]. Studies generally reported a significant relationship between sleep duration and suicidal ideation [41•, 48, 49] such that less sleep was associated with increased frequency or intensity of suicidal ideation. In addition to ideation, another study that utilized data from suicide decedents reported a similar and significant relationship between sleep duration and suicide risk [14•]. The exception to this trend was a 2014 study of US military veterans receiving primary care services conducted by Chakravorty and colleagues [42] that did not find a significant relationship. While cross-sectional in nature, these studies provide a significant step forward in that they incrementally move the examination of the sleep-suicide relationship towards measures of sleep continuity and mechanism and away from global constructs of impairment.

Circadian Rhythm

Circadian rhythm and sleep rhythmicity were examined in two articles included as part of this review [15, 50]. The studies found that both lifetime problems with rhythmicity and having an eveningness chronotype were associated with an increased likelihood of suicidal ideation. Chan and colleagues’ 2014 [50] study utilizing a sample of outpatients diagnosed with major depressive disorder (N = 253) also reported a significant relationship between lifetime history of suicide attempt and eveningness chronotype. However, in Dell’Osso and colleagues’ 2014 [15] investigation of individuals diagnosed with posttraumatic stress disorder (N = 65), the relationship between rhythmicity and history of a suicide attempt was nonsignificant. It is premature to draw conclusions on the relationship among circadian factors and suicidality given the limited number of studies that examined during this time period.

Sleep Apnea

Two studies examined suicidal ideation in the context of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). Choi and colleagues [35] investigated the association between insomnia and suicidal ideation among participants diagnosed with OSA. They reported a weak association between greater insomnia (i.e., higher ISI total score) and greater suicidal ideation (as measured by a single item). This relationship was no longer significant after controlling for depression symptom severity. This study is actually included in the insomnia section of Table 1, but is discussed here as it provided one of the initial estimates of the prevalence of suicidal ideation among individuals diagnosed with OSA as 20.5 % of their sample (N = 117) reported at least some suicidal ideation. Edwards and colleagues [51•] built on this literature with a recent examination of the role that treatment for OSA played in depression severity. They reported significant reductions in suicidal ideation at 3-month follow-up among a subsample of patients with OSA who utilized continuous positive airway pressure and who had reported suicidal ideation at baseline. The study unfortunately again only used a single item to assess suicidal ideation and excluded a large number of their initial sample that was non-adherent to CPAP, limiting the inferences that can be drawn from the data.

Military Veterans

Nine of the articles reviewed utilized a veteran sample [11, 13, 19, 23•, 24, 34, 40, 41•, 42]. The relationship between sleep problems and suicide among veterans is of particular interest given the prevalence of sleep problems and elevated rate of suicide in this population. Of the nine studies reviewed that used veteran samples, four reported on insomnia symptoms, three indicated a positive association between insomnia symptoms and suicidal ideation [23•, 24, 42], whereas one reported the relationship as non-significant [34]. However, in the Chakravorty and colleagues study [42], the relationship between insomnia symptoms and SI was no longer significant when part of a multivariate model that controlled for other psychopathology. In this subset of studies, self-reported sleep quality demonstrated the most robust relationship to SI, as poorer sleep quality often remained significantly associated with increased likelihood or severity of SI when controlling for other risk factors [41•, 42] and in one study improved sleep quality mediated the relationship between an exercise intervention and improvements in suicidal ideation [40]. Other metrics of sleep problems were often no longer significant when included as part of multivariate analyses that accounted for co-occurring psychopathology (e.g., sleep duration [34, 42] and nightmares [34]). Additionally, and as described above, Pigeon and colleagues (2012) [11] provided data among a sample of veteran decedents indicating that the presence of sleep disturbance decreases survival time from last VHA visit.

In sum, eight of nine studies among veterans reported at least one significant association between a sleep variable and the presence or severity of SI. As in the broader literature, however, as the operationalization of sleep-related variables become more precise, their robustness as a risk factor for suicide lessens. While these findings add to the existing literature among veterans, they also highlight the need for future prospective work in this population.

Conclusions

The present report reviewed 41 articles published between January 1, 2012 and January 1, 2016 that examined the relationship of sleep variables to suicidal thought and behavior. Consistent with prior reviews, generalized sleep disturbance, insomnia, and nightmares were, overall, positively associated with suicidal thought and behavior.

There are some notable limitations to this review. Although articles were systematically selected, we did not assess quality of studies, nor were studies included or excluded on this basis. We also did not limit studies based on sample size. An additional limitation of this review is the focus on the presence or absence of statistically significant signals indicating a relationship between sleep and suicide. There is no discussion of the magnitude and/or effect size of the findings or a nuanced examination of potential confounders (e.g., prevalence of sedative-hypnotic use among study participants).

Nonetheless, the preponderance of studies controlled for psychopathology in some manner, which represents an advance as this has previously been noted as a shortcoming in the extant literature [52]. In a 2012 meta-analysis [7], there were no studies undertaken in military or veteran populations; the addition of nine such articles since that time also represents a needed advance.

The review reveals that several gaps remain in the literature. First, most of the studies reviewed are cross-sectional in nature precluding a thorough review of the longitudinal association of sleep disturbance with subsequent suicidal thoughts or behaviors. Eight of 41 studies were longitudinal in design, although three were retrospective chart review or psychological autopsy studies of suicide decedents [11, 16, 37]. Two of the longitudinal studies actually identified suicide decedents from long-term, prospective studies [14•, 30•], and three were prospective studies where suicidal ideation [17•, 23•, 29•] and/or suicide attempt [23•] were the outcomes of interest. Additional prospective studies are needed.

Second, the large majority of studies focused on suicidal ideation as an outcome, whereas far fewer focused on suicide attempts or suicide. This is true in the broader suicide literature as well and is not unexpected given that non-fatal suicide attempts, and certainly suicide, have low incidence rates. While suicidal ideation is an important outcome or occurrence, additional studies revealing that sleep disturbance or specific sleep disorders are robustly associated with suicidal behaviors would bolster the case for sleep problems representing an important modifiable risk factor for suicide.

Third, several important areas remain under-represented in the sleep-suicide literature. These include the association of objective measures of sleep architecture to suicide, for which no new studies were identified. In addition, only one study reported on the association of hypnotic medication use to suicide [33•]. Similarly, only one study assessed the association of OSA to suicide [51•]. Each of these three areas represents important areas of inquiry that remain gaps in the sleep-suicide literature.

In summary, prior reviews and meta-analyses have consistently supported a strong relationship between a variety of sleep problems and/or sleep disorders and the presence of suicidal thought and behavior, while acknowledging some shortcomings in the literature. The current review of the most recent sleep-suicide literature, first, lends further support to the presence of a sleep-suicide association. Second, there appears to be a trend to include appropriate statistical control for psychopathology, which strengthens the argument that sleep/sleep disturbance contributes independently to suicide risk.

Third, albeit modest in number, the addition of several studies using solid prospective designs also contributes to the argument for a causal link between sleep disturbance and suicidal thought and behavior. Finally, the review revealed an ongoing lack of sufficient information about the contribution of sleep apnea, hypnotic medications, and polysomnography-measured sleep to suicide risk and outcomes.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance

Xu JQ, Kochanek KD, Murphy SL, Arias E (2014) Mortality in the United States, 2012. NCHS Data Brief, no 168.

Curtin S, Warner M, Hedegaard H (2016) Increase in suicide in the United States, 1999–2014. Data Brief, no. 241.

Baglioni C, Battagliese G, Feige B, Spiegelhalder K, Nissen C, Voderholzer U, et al. Insomnia as a predictor of depression: a meta-analytic evaluation of longitudinal epidemiological studies. J Affect Disord. 2011;135:10–9.

Baglioni C, Riemann D. Is chronic insomnia a precursor to major depression? Epidemiological and biological findings. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2012;14:511–8.

Germain A. Sleep disturbances as the hallmark of PTSD: where are we now? Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170:372–82.

Bernert RA, Joiner Jr TE, Cukrowicz KC, Schmidt NB, Krakow B. Suicidality and sleep disturbances. Sleep. 2005;28:1135–41.

Pigeon WR, Pinquart M, Conner K. Meta-analysis of sleep disturbance and suicidal thoughts and behaviours. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73:1160–7.

McCall WV, Black CG. The link between suicide and insomnia: theoretical mechanisms. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2013;15:389. doi:10.1007/s11920-013-0389-9.

Woznica AA, Carney CE, Kuo JR, Moss TG. The insomnia and suicide link: toward an enhanced understanding of this relationship. Sleep Med Rev. 2015;22:37–46. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2014.10.004.

Pigeon WR, Caine ED. Insomnia and the risk for suicide: does sleep medicine have interventions that can make a difference? Sleep Med. 2010;11:816–7.

Pigeon WR, Britton P, Ilgen MA, Chapman BP, Conner KR. Sleep disturbance preceding suicide among veterans. Am J Public Health. 2012;S1:93–7.

Betts KS, Williams GM, Najman JM, Alati R. The role of sleep disturbance in the relationship between post-traumatic stress disorder and suicidal ideation. J Anxiety Disord. 2013;27:735–41. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.09.011.

Bishop TM, Pigeon WR, Possemato K. Sleep disturbance and its association with suicidal ideation in Veterans. Mil Behav Health. 2013;1:81–4. doi:10.1080/21635781.2013.830061.

Gunnell D, Chang SS, Tsai MK, Tsao CK, Wen CP. Sleep and suicide: an analysis of a cohort of 394,000 Taiwanese adults. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2013;48:1457–65. doi:10.1007/s00127-013-0675-1. A cohort of nearly 400,000 individuals was used to assess the hazard ratios of baseline sleep duration and sleep problems for suicide mortality adjusted for a host of factors.

Dell’Osso L, Massimetti G, Conversano C, Bertelloni CA, Carta MG, Ricca V, et al. Alterations in circadian/seasonal rhythms and vegetative functions are related to suicidality in DSM-5 PTSD. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:352. doi:10.1186/s12888-014-0352-2.

Kodaka M, Matsumoto T, Katsumata Y, Akazawa M, Tachimori H, Kawakami N, et al. Suicide risk among individuals with sleep disturbances in Japan: a case-control psychological autopsy study. Sleep Med. 2014;15:430–5. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2013.11.789.

Nadorff MR, Ellis TE, Allen JG, Winer ES, Herrera S. Presence and persistence of sleep-related symptoms and suicidal ideation in psychiatric inpatients. Crisis. 2014;35:398–405. doi:10.1027/0227-5910/a000279. Sleep symptoms and suicidal ideation were assessed at baseline and over the course of an average six week inpatients stay among over 1,500 inpatients.

Jia CX, Zhang WC, Wei L, Zhang JY, Liu XC. Sleep disturbance and attempted suicide in rural China: a case-control study. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2015;203:463–8. doi:10.1097/NMD.0000000000000304.

McClure JR, Criqui MH, Macera CA, Ji M, Nievergelt CM, Zisook S. Prevalence of suicidal ideation and other suicide warning signs in veterans attending an urgent care psychiatric clinic. Compr Psychiatry. 2015;60:149–55. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2014.09.010.

Sit D, Luther J, Buysse D, Dills JL, Eng H, Okun M, et al. Suicidal ideation in depressed postpartum women: associations with childhood trauma, sleep disturbance and anxiety. J Psychiatr Res. 2015;66–67:95–104. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2015.04.021.

Chiu HF, Dai J, Xiang YT, Chan SS, Leung T, Yu X, et al. Suicidal thoughts and behaviors in older adults in rural China: a preliminary study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;27:1124–30. doi:10.1002/gps.2831.

Li SX, Lam SP, Chan JW, Yu MW, Wing YK. Residual sleep disturbances in patients remitted from major depressive disorder: a 4-year naturalistic follow-up study. Sleep. 2012;35:1153–61. doi:10.5665/sleep.2008.

Ribeiro JD, Pease JL, Gutierrez PM, Silva C, Bernert RA, Rudd MD, et al. Sleep problems outperform depression and hopelessness as cross-sectional and longitudinal predictors of suicidal ideation and behavior in young adults in the military. J Affect Disord. 2012;136:743–50. This study was the first to measure cross-sectional and longitudinal relationships between insomnia symptoms and suicidal ideation and behavior, controlling for depressive PTSD, anxiety, and substance abuse in military personnel.

Bryan CJ, Clemans TA, Hernandez AM, Rudd MD. Loss of consciousness, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, and suicide risk among deployed military personnel with mild traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2013;28:13–20. doi:10.1097/HTR.0b013e31826c73cc.

Klimkiewicz A, Bohnert AS, Jakubczyk A, Ilgen MA, Wojnar M, Brower K. The association between insomnia and suicidal thoughts in adults treated for alcohol dependence in Poland. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;122:160–3. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.09.021.

Maniam T, Chinna K, Lim CH, Kadir AB, Nurashikin I, Salina AA, et al. Suicide prevention program for at-risk groups: pointers from an epidemiological study. Prev Med. 2013;57(Suppl):S45–6. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.02.022.

Nadorff MR, Nazem S, Fiske A. Insomnia symptoms, nightmares, and suicide risk: duration of sleep disturbance matters. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2013;43:139–49. doi:10.1111/sltb.12003.

Pompili M, Innamorati M, Forte A, Longo L, Mazzetta C, Erbuto D, et al. Insomnia as a predictor of high-lethality suicide attempts. Int J Clin Pract. 2013;67:1311–6. doi:10.1111/ijcp.12211.

Suh S, Kim H, Yang HC, Cho ER, Lee SK, Shin C. Longitudinal course of depression scores with and without insomnia in non-depressed individuals: a 6-year follow-up longitudinal study in a Korean cohort. Sleep. 2013;36:369–76. doi:10.5665/sleep.2452. This longitudinal study of 1,282 non-depressed individuals investigated the longitudinal associations between insomnia and depression, and insomnia and suicidal ideation over a six year period.

Bernert RA, Turvey CL, Conwell Y, Joiner Jr TE. Association of poor subjective sleep quality with risk for death by suicide during a 10-year period: a longitudinal, population-based study of late life. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71:1129–37. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1126. Twenty suicide decedents from a large epidemiolgic study were matched to 400 controls to assess the association of sleep items and total sleep quality index to suicide controlling for depression severity.

Kato T. Insomnia symptoms, depressive symptoms, and suicide ideation in Japanese white-collar employees. Int J Behav Med. 2014;21:506–10. doi:10.1007/s12529-013-9364-4.

Nadorff MR, Anestis MD, Nazem S, Claire HH, Samuel WE. Sleep disorders and the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicide: independent pathways to suicidality? J Affect Disord. 2014;152–154:505–12. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2013.10.011.

Pigeon WR, Woosley JA, Lichstein KL. Insomnia and hypnotic medications are associated with suicidal ideation in a community population. Arch Suicide Res. 2014;18:170–80. doi:10.1080/13811118.2013.824837. Based on one of the few community-wide studies using a battery of well-validated instruments, this secondary analysis examined the association of hypnotic medications to suicidal ideation, while controlling for a variety of demographic and clinical variables.

Richardson JD, Cyr KS, Nelson C, Elhai JD, Sareen J. Sleep disturbances and suicidal ideation in a sample of treatment-seeking Canadian Forces members and veterans. Psychiatry Res. 2014;218:118–23. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2014.04.008.

Choi SJ, Joo EY, Lee YJ, Hong SB. Suicidal ideation and insomnia symptoms in subjects with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Sleep Med. 2015;16:1146–50. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2015.04.026.

Golding S, Nadorff MR, Winer ES, Ward KC. Unpacking sleep and suicide in older adults in a combined online sample. J Clin Sleep Med. 2015;11:1385–92. doi:10.5664/jcsm.5270.

Sun L, Zhang J, Liu X. Insomnia symptom, mental disorder and suicide: a case-control study in Chinese rural youths. Sleep Biol Rhythms. 2015;13:181–8. doi:10.1111/sbr.12105.

Lai YC, Huang MC, Chen HC, Lu MK, Chiu YH, Shen WW, et al. Familiality and clinical outcomes of sleep disturbances in major depressive and bipolar disorders. J Psychosom Res. 2014;76:61–7. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2013.10.020.

Marinova P, Koychev I, Laleva L, Kancheva L, Tsvetkov M, Bilyukov R, et al. Nightmares and suicide: predicting risk in depression. Psychiatr Danub. 2014;26:159–64.

Davidson CL, Babson KA, Bonn-Miller MO, Souter T, Vannoy S. The impact of exercise on suicide risk: examining pathways through depression, PTSD, and sleep in an inpatient sample of veterans. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2013;43:279–89.

Swinkels CM, Ulmer CS, Beckham JC, Buse N, Calhoun PS. The association of sleep duration, mental health, and health risk behaviors among U.S. Afghanistan/Iraq Era veterans. Sleep. 2013;36:1019–25. doi:10.5665/sleep.2800. A cross sectional-study of 1,640 combat veterans included 20% women veterans and assessed the association of sleep duration and sleep quality with mental health and suicidal ideation.

Chakravorty S, Grandner MA, Mavandadi S, Perlis ML, Sturgis EB, Oslin DW. Suicidal ideation in veterans misusing alcohol: relationships with insomnia symptoms and sleep duration. Addict Behav. 2014;39:399–405. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.09.022.

Racine M, Choiniere M, Nielson WR. Predictors of suicidal ideation in chronic pain patients: an exploratory study. Clin J Pain. 2014;30:371–8. doi:10.1097/AJP.0b013e31829e9d4d.

Wigg CM, Filgueiras A, Gomes MM. The relationship between sleep quality, depression, and anxiety in patients with epilepsy and suicidal ideation. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2014;72:344–8.

Calandre EP, Navajas-Rojas MA, Ballesteros J, Garcia-Carrillo J, Garcia-Leiva JM, Rico-Villademoros F. Suicidal ideation in patients with fibromyalgia: a cross-sectional study. Pain Pract. 2015;15:168–74. doi:10.1111/papr.12164.

Gelaye B, Barrios YV, Zhong QY, Rondon MB, Borba CP, Sanchez SE, et al. Association of poor subjective sleep quality with suicidal ideation among pregnant Peruvian women. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2015;37:441–7. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2015.04.014.

Trinanes Y, Gonzalez-Villar A, Gomez-Perretta C, Carrillo-de-la-Pena MT. Suicidality in chronic pain: predictors of suicidal ideation in fibromyalgia. Pain Pract. 2015;15:323–32. doi:10.1111/papr.12186.

Bae SM, Lee YJ, Cho IH, Kim SJ, Im JS, Cho SJ. Risk factors for suicidal ideation of the general population. J Korean Med Sci. 2013;28:602–7. doi:10.3346/jkms.2013.28.4.602.

Kim JH, Park EC, Cho WH, Park CY, Choi WJ, Chang HS. Association between total sleep duration and suicidal ideation among the Korean general adult population. Sleep. 2013;36:1563–72. doi:10.5665/sleep.3058.

Chan JW, Lam SP, Li SX, Yu MW, Chan NY, Zhang J, et al. Eveningness and insomnia: independent risk factors of nonremission in major depressive disorder. Sleep. 2014;37:911–7.

Edwards C, Mukherjee S, Simpson L, Palmer LJ, Almeida OP, Hillman DR. Depressive symptoms before and after treatment of obstructive sleep apnea in men and women. J Clin Sleep Med. 2015;11:1029–38. doi:10.5664/jcsm.5020. One of the few studies to assess the relationship of obstructive sleep apnea to suicide, this study assessed depressive symptoms among 426 consecutive patients before and after CPAP therapy.

Bernert RA, Joiner TE. Sleep disturbances and suicide risk: a review of the literature. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2007;3:735–43.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the VISN 2 Center of Excellence for Suicide Prevention at the Canandaigua VAMC. The authors’ views or opinions do not necessarily represent those of the Department of Veterans Affairs, the National Institutes of Health, or the US Government.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Wilfred R. Pigeon and Caitlin E. Titus declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Todd M. Bishop is supported, in part, by the VA Advanced Fellowship Program in Mental Health Illness Research and Treatment.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Sleep and Psychological Disorders

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pigeon, W.R., Titus, C.E. & Bishop, T.M. The Relationship of Suicidal Thoughts and Behaviors to Sleep Disturbance: a Review of Recent Findings. Curr Sleep Medicine Rep 2, 241–250 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40675-016-0054-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40675-016-0054-z