Abstract

Introduction

In general, church attendance can be associated with improved health behaviors and fewer related chronic diseases, suggesting a potential opportunity to counteract worsening health behaviors among some immigrants and thereby reduce health disparities. There is a paucity of research, however, on the relationship between religious involvement and immigrants’ health behaviors and whether it varies by host or home country context.

Aim

To examine the relationship between religious involvement, measured by church attendance, with health behaviors among Latino immigrants in the United States (U.S.) and to compare the relationship of home and host country attendance with these behaviors.

Methods

Data from the randomized New Immigrant Survey, including over 1200 immigrants to the U.S. from Mexico and Central America, were analyzed. Health measures included smoking, binge drinking, physical activity, and obesity. Descriptive and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed using measures of church attendance and ethnic/immigrant characteristics as well as other demographic and health care factors. Separate models were constructed for each behavior.

Results

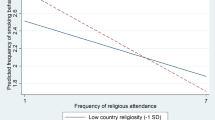

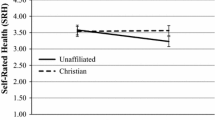

An association was found between U.S. church attendance and less smoking, less drinking, and greater physical activity but not with obesity. Threshold effects were found. However, almost no associations were found between health behaviors and home country church attendance.

Conclusion

The context in which people live warrants increased attention for successful health promotion initiatives for immigrant populations. The social, psychological, and religious resources in immigrant communities can be leveraged to potentially counteract worsening of chronic disease-related health behaviors of Latino immigrants in the U.S., thereby reducing health disparities.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Center for Communicable Diseases. Chronic disease and health promotion. 2017. http://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease. Accessed 4 December 2017.

World Health Organization. Noncommunicable diseases factsheet. 2017. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs355/en/. Accessed 4 December 2017.

Ellison C, Levin J. The religion-health connection: evidence, theory and future directions. Health Educ Behav. 1998;25:700–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/109019819802500603.

Koenig H, Kind D, Carson V. Handbook of religion and health. Second ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2012.

Krause N, Hill P, Emmons R, Pargament K, Ironson G. Assessing the relationship between religious involvement and health behaviors. Health Educ Behav. 2017;44:278–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198116655314.

Headey B, Hoehne G, Wagner GG. Does religion make you healthier and longer lived? Evidence for Germany. Soc Indic Res. 2014;119(3):1335–61.

Stark R. Religion and conformity. In: Day J, Laufer W, editors. Crimes, values, and religion. Norwood: Ablex; 1987. p. 111–20.

Ford J. Some implications of denominational heterogeneity and church attendance for alcohol consumption among Hispanics. J Sci Study Relig. 2006;45(20):253–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5906.2006.00304.x.

Hill T, Ellison CG, Burdette A, Musick M. Religious involvement and healthy lifestyles. Ann Behav Med. 2007;34(2):217–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/08836610701566993.

Benjamins MR, Ellison CG, Krause NM, Marcum JP. Religion and preventive service use: do congregational support and religious beliefs explain the relationship between attendance and utilization? J Behav Med. 2011;34(6):462–76.

Idler E. Religion as a social determinant of public health. New York: Oxford University Press; 2014.

Chatters L. Religion and health: public health research and practice. Ann Rev Public Health. 2000;21:355–67.

Levin J. God, faith, and health: exploring the spirituality-healing connection. New York: Wiley; 2001.

Garrusi B, Nakhaee N. Religion and smoking: a review of recent literature. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2012;43(3):279–92.

Feinstein M, Liu K, Ning H, Fitchett G, Lloyd-Jones DM. Incident obesity and cardiovascular risk factors between young adulthood and middle age by religious involvement. Prev Med. 2012;54(2):117–21.

Godbolt D, Vaghela P, Burdette, et al. Religious attendance and body mass: an examination of variations by race and gender. J Relig Health. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-017-0490-1.

Lara M, Gamboa C, Kahramanian I, Morales L, Bautista D. Acculturation and Latino health in the United States: a review of the literature and its sociopolitical context. Ann Rev Public Health. 2005;26:367–97. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144615.

Markides K, Eschbach K. Aging, migration, and mortality: current status of research on the Hispanic paradox. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2005;60(spec 2):68–75.

Rumbaut RG. Assimilation and its discontents: between rhetoric and reality. Int Migr Rev. 1997;31(4):923–60.

Pargament KI. APA handbook of psychology, religion, and spirituality. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2013.

Vega WA, Rodriguez MA, Gruskin E. Health disparities in the Latino population. Epidemiol Rev. 2009;31(1):99–112. https://doi.org/10.1093/epirev/mxp008.

Garcia G, Ellison CG, Sunil T. Religion and selected health behaviors among Latinos in Texas. J Relig Health. 2013;52(1):18–31.

Kegler M, Hall S, Kiser M. Facilitators, challenges, and collaborative activities in faith and health partnerships to address health disparities. Health Educ Behav. 2010;37(5):665–79. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198110363882.

Powell L, Shahabi L, Thoresen C. Religion and spirituality: linkages to physical health. Am Psychol. 2003;58(1):43–52.

Berkman L, Kawachi I, editors. Social epidemiology. New York: Oxford University Press; 2014.

Eriksson M. Social capital and health—implications for health promotion. Glob Health Action. 2011;4:5611.

Putnam R. Bowling alone. New York: Simon and Schuster; 2000.

Avalos H. Introduction to the U.S. Latina and Latino religious experience. Boston: Brill Academic Publishers; 2004.

Putnam R, Campbell D. American grace: how religion divides and unites us. New York: Simon and Schuster; 2011.

Steffen PR, Masters KS. Does compassion mediate the intrinsic religion-health relationship? Ann Behav Med. 2005;30(3):217–24.

Park JZ, Smith C. ‘To whom much has been given…’: religious capital and community voluntarism among churchgoing Protestants. J Sci Study Relig. 2000;39(3):272–86.

Kim ES, Konrath SH. Volunteering is prospectively associated health care use among older adults. Soc Sci Med. 2016;149(c):122–9.

Krause N. Church-based social support and change in health over time. Rev Relig Res. 2006;48(2):125–40.

Sloan R. Blind faith. New York: St. Martin’s Press; 2006.

Iannacone L. Religious practice: a human capital approach. J Sci Study Relig. 1990;29(3):297–314.

Portes A. Social capital: its origins and applications in modern sociology. Annu Rev Sociol. 1998;24:1–24.

Stauner N, Exline JJ, Pargament KI. Religious and spiritual struggles as concerns for health and well-being. Horizonte. 2016;14(41):48–75.

Solano J. The Central American religious experience in the U.S: Salvadorans and Guatemalans as case studies. In: Avalos H, editor. Introduction to the U.S. Latina and Latino religious experience. Boston: Brill Academic Publishers; 2004. p. 116–142.

Portes A, Rumbaut R. Immigrant America: a portrait. Fourth ed. Oakland: University of California Press; 2014.

Warner R, Warner G. Gatherings in diaspora: religious communities and the new immigration. Philadelphia: Temple University Press; 1998.

Foley M, Hoge T. Religion and the new immigrants: how faith communities form our newest citizens. New York: Oxford University Press; 2007.

Pew Research Center. The shifting religious identity of Latinos in the United States. 2014. http://www.pewforum.org/2014/05/07/theshifting-religious-identity-of-latinos-in-the-united-states. Accessed 23 Feb 2018.

Massey DS, Higgins ME. The effect of immigration on religious belief and practice: a theologizing or alienating experience. Soc Sci Res. 2011;40(5):1371–89.

Nicholson A, Rose R, Bobek M. Association between attendance at religious services and self-reported health in 22 European countries. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(4):519–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.06.024.

Connor P. International migration and religious participation: the mediating impact of individual and contextual effects. Sociol Forum. 2009;24(4):779–803.

Newlin K, Dyess SM, Allard E, Chase S, Melkus GD. A methodological review of faith-based health promotion literature: advancing the science to expand delivery of diabetes education to Black Americans. J Relig Health. 2012;51(4):1075–97.

Campbell MK, Hudson MA, Resnicow K, Blakeney N, Paxton A, Baskin M. Church-based health promotion interventions: evidence and lessons learned. Annu Rev Public Health. 2007;28:213–34.

Schwingel A, Glavez P. Divine interventions: faith-based approaches to health promotion programs for Latinos. J Relig Health. 2015;56(3):1052–63.

Department of Health, United Kingdom. Health and well-being. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/278140/Health_Behaviours_and_Wellbeing.pdf. Accessed 23 Feb 2018.

American Cancer Society. How smoking tobacco affects your cancer risk. Available at https://www.cancer.org/cancer/cancer-causes/tobacco-and-cancer/health-risks-of-smoking-tobacco.html. Accessed 23 Feb 2018.

Naimi TS, Brewer RD, Mokdad A, Clark D, et al. Binge drinking among US adults. JAMA. 2013;289(1):70–5.

He X, Baker D. Body mass index, physical activity, and the risk of decline in overall health and physical functioning in late middle age. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:1567–73.

Kaplan S, Caiman N, Golub M, Ruddock C, Billings J. The role of faith based institutions in addressing health disparities. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2006;7(2 suppl):9–19. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2006.0088.

Arredondo E, Elder J, Ayala G, Campbell N. Fe en Acción: Promoting physical activity among churchgoing Latinas. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(7):1109–15.

Silfee V, Haughton C, Lemon S, Lora V, Rosal M. Spirituality and physical activity and sedentary behavior among Latino men and women in Massachusetts. Ethn Dis. 2017;27(1):3–10.

Abraído-Lanza A, Chao M, Florez K. Do healthy behaviors decline with greater acculturation? Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(6):1243–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.01.016.

Trinitapoli J, Ellison CG, Boardman JD. U.S. religious congregations and the sponsorship of health-related programs. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68(2):2231–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.03.036.

Rozier M. Religion and public health: moral tradition as both problem and solution. J Relig Health. 2015;55(6):1891–906.

Baig AA, Benitez A, Locklin CA, et al. Picture good health; a church-based self-management intervention among Latino adults with diabetes. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(10):1481–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-015-3339-x.

Gross T, Story C, Harvey I, Whitt-Glover M. Pastors’ perceptions on the health status of the Black church and African-American communities. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2017; https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-017-0401-x.

Krause N, Shaw B, Liang J. Social relationships in religious institutions and healthy lifestyles. Health Educ Behav. 2011;38(1):25–38.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to acknowledge the assistance of the following during the course of the research and writing of this paper: Ana Abraído-Lanza, PhD; Angela Aidala, PhD; Nancy Foner, PhD; Joyce Moon-Howard, DrPH; Courtney Bender, PhD; and Victor Rodwin, PhD.

Funding

This study did not receive any funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The survey used in the study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Princeton University.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval (Animals)

This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Ethical Approval (Human Subjects)

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shapiro, E. Places of Habits and Hearts: Church Attendance and Latino Immigrant Health Behaviors in the United States. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 5, 1328–1336 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-018-0481-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-018-0481-2