Abstract

Purpose of review

This review aims to provide an overview of recent neurodevelopmental network models of PTSD in youth as an avenue towards a better understanding of treatment options for this group. Present empirically supported psychosocial intervention components for youth exposed to trauma in the context of the neurodevelopmental network model of PTSD in youth.

Recent findings

Key brain regions and regional connections implicated in childhood trauma may be targeted by the specific components taught in interventions. Intervention components may have differential use and effectiveness by community therapists and depending on patient presentation.

Summary

Treatments for PTSD in youth are effective with cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) and eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) techniques among the psychosocial treatment options endorsed for use. Researchers have begun to identify the most successful and commonly used components of treatments. The current review identifies components of CBT and EMDR, their potential for packaging to meet patient profiles and main presenting issues, and also discusses the augmentation of exposure techniques with D-cycloserine (DCS) and other options such as cue-centered therapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

References and Recommended Reading

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance

Bradley R, Greene J, Russ E, Dutra L, Westen D. A multidimensional meta-analysis of psychotherapy for PTSD. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(2):214–27.

Cohen JA, Mannarino AP, Deblinger E. Treating trauma and traumatic grief in children and adolescents. New York: Guilford Press; 2006.

Chambless DL, Hollon SD. Defining empirically supported therapies. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1998;66(1):7–18.

American Psychological Association. Evidence-based practice in psychology. Am Psychol. 2006;61(4):271–85.

Costello EJ, Erkanli A, Fairbank JA, Angold A. The prevalence of potentially traumatic events in childhood and adolescence. J Trauma Stress. 2002;15(2):99–112.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th edition: DSM-5 ed. Washington: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

Bonanno GA, Brewin CR, Kaniasty K, Greca AML. Weighing the costs of disaster: consequences, risks, and resilience in individuals, families, and communities. Psychol Sci Public Interest. 2010;11(1):1–49.

Kendall-Tackett KA, Williams LM, Finkelhor D. Impact of sexual abuse on children: a review and synthesis of recent empirical studies. Psychol Bull. 1993;113(1):164–80.

Weems CF, Graham RA. Resilience and trajectories of posttraumatic stress among youth exposed to disaster. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2014;24(1):2–8.

Calhoun LG, Tedeschi RG. The foundations of posttraumatic growth: An expanded framework. In: In: Handbook of posttraumatic growth: research and practice. New York: Routledge; 2006. p. 17–37.

Prati G, Pietrantoni L. Optimism, social support, and coping strategies as factors contributing to posttraumatic growth: a meta-analysis. J Loss Trauma. 2009;14(5):364–88.

Haskett ME, Nears K, Ward CS, McPherson AV. Diversity in adjustment of maltreated children: Factors associated with resilient functioning. Clin Psychol Rev. 2006;26(6):796–812.

Kerig PK. Linking childhood trauma exposure to adolescent justice involvement: the concept of posttraumatic risk-seeking. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2019;26:e12280.

• Russell JD, Neill EL, Carrión VG, Weems CF. The network structure of posttraumatic stress symptoms in children and adolescents exposed to disasters. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;56(8):669–77 Provides a review and first empirical study of the network structure of PTSD symptoms in youth.

• Weems CF, Russell JD, Neill EL, McCurdy BH. Annual research review: pediatric posttraumatic stress disorder from a neurodevelopmental network perspective. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2019;60(4):395–408 Presents the neurodevelopmental network perspective.

Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA. Equifinality and multifinality in developmental psychopathology. Dev Psychopathol. 1996;8(4):597–600.

• Carrión VG, Weems C. Neuroscience of pediatric PTSD. Oxford University Press; 2017. Summary of the literature on the neuroscience of pediatric PTSD.

Weems CF, Saltzman KM, Reiss AL, Carrion VG. A prospective test of the association between hyperarousal and emotional numbing in youth with a history of traumatic stress. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2003;32(1):166–71.

• Herringa RJ. Trauma, PTSD, and the developing brain. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2017;19(10):69–85 Summary of research on Trauma and the developing brain.

Menon V. Large-scale brain networks and psychopathology: a unifying triple network model. Trends Cogn Sci. 2011;15(10):483–506.

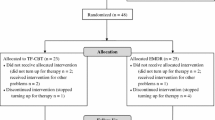

Carrion VG, Kletter H, Weems CF, Berry RR, Rettger JP. Cue-centered treatment for youth exposed to interpersonal violence: a randomized controlled trial. J Trauma Stress. 2013;26(6):654–62.

Scheeringa MS, Weems CF. Randomized placebo-controlled D-Cycloserine with cognitive behavior therapy for pediatric posttraumatic stress. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2014;24(2):69–77.

Scheeringa MS, Weems CF, Cohen JA, Amaya-Jackson L, Guthrie D. Trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder in three-through six year-old children: a randomized clinical trial. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2011;52(8):853–60.

Taylor LK, Weems CF. Cognitive-behavior therapy for disaster-exposed youth with posttraumatic stress: results from a multiple-baseline examination. Behav Ther. 2011;42(3):349–63.

Weems CF, Taylor LK, Costa NM, Marks AB, Romano DM, Verrett SL, et al. Effect of a school-based test anxiety intervention in ethnic minority youth exposed to Hurricane Katrina. J Appl Dev Psychol. 2009;30(3):218–26.

• ISTSS Guidelines Committee. Posttraumatic stress disorder prevention and treatment guidelines: methodology and recommendations [Internet]. Oakbrook Terrace, IL: International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies; 2018 [cited 2019 May 31]. Available from: http://www.istss.org/getattachment/Treating-Trauma/New-ISTSS-Prevention-and-Treatment-Guidelines/ISTSS_PreventionTreatmentGuidelines_FNL-March-19-2019.pdf.aspx. Treatment Guidelines for PTSD.

Silverman WK, Ortiz CD, Viswesvaran C, Burns BJ, Kolko DJ, Putnam FW, et al. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children and adolescents exposed to traumatic events. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2008;37(1):156–83.

Ramirez de Arellano MA, Lyman DR, Jobe-Shields L, George P, Dougherty RH, Daniels AS, et al. Trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy for children and adolescents: assessing the evidence. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(5):591–602.

Foa EB, Keane TM, Friedman MJ, Cohen JA, editors. Effective treatments for PTSD: practice guidelines from the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies. New York: Guilford Press; 2009.

Schubert S, Lee CW. Adult PTSD and its treatment with EMDR: a review of controversies, evidence, and theoretical knowledge. J EMDR Pract Res. 2009;3(3):117–32.

van der Kolk BA, Spinazzola J, Blaustein ME, Hopper JW, Hopper EK, Korn DL, et al. A randomized clinical trial of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR), fluoxetine, and pill placebo in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder: treatment effects and long-term maintenance. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(1):37–47.

Mowrer OH. Learning theory and behavior. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1960.

Kowalik J, Weller J, Venter J, Drachman D. Cognitive behavioral therapy for the treatment of pediatric posttraumatic stress disorder: a review and meta-analysis. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2011;42(3):405–13.

Cohen JA, Deblinger E, Mannarino A. Trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy for sexually abused children. Psychiatr Times. 2004;21(10):109–21.

Cohen JA, Deblinger E, Mannarino AP, Steer RA. A multisite, randomized controlled trial for children with sexual abuse–related PTSD symptoms. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43(4):393–402.

Cohen JA, Mannarino AP. A treatment outcome study for sexually abused preschool children: Initial findings. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;35(1):42–50.

Cohen JA, Mannarino AP. Factors that mediate treatment outcome of sexually abused preschool children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;35(10):1402–10.

Cohen JA, Mannarino AP. A treatment study for sexually abused preschool children: outcome during a one-year follow-up. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36(9):1228–35.

Deblinger E, Lippmann J, Steer R. Sexually abused children suffering posttraumatic stress symptoms: initial treatment outcome findings. Child Maltreat. 1996;1(4):310–21.

Deblinger E, Stauffer LB, Steer RA. Comparative efficacies of supportive and cognitive behavioral group therapies for young children who have been sexually abused and their nonoffending mothers. Child Maltreat. 2001;6(4):332–43.

Deblinger E, Steer RA, Lippmann J. Two-year follow-up study of cognitive behavioral therapy for sexually abused children suffering post-traumatic stress symptoms. Child Abuse Negl. 1999;23(12):1371–8.

King NJ, Tonge BJ, Mullen P, Myerson N, Heyne D, Rollings S, et al. Treating sexually abused children with posttraumatic stress symptoms: a randomized clinical trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39(11):1347–55.

Pollio E, McLean M, Behl LE, Deblinger E. Trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy. In: Reece RM, Hanson RF, Sargent J, editors. Treatment of child abuse: common ground for mental health, medical, and legal practitioners. 2nd ed. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2014. p. 31–8.

Shapiro F. Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing: Basic principles, protocols, and procedures. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2001.

Oren E, Solomon R. EMDR therapy: an overview of its development and mechanisms of action. Rev. Eur Psychol AppliquéeEuropean Rev. Appl Psychol. 2012;62(4):197–203.

Aubert-Khalfa S, Roques J, Blin O. Evidence of a decrease in heart rate and skin conductance responses in PTSD patients after a single EMDR session. J EMDR Pract Res. 2008;2(1):51–6.

Neill EL. The use of empirically supported treatment components for trauma exposure: the role of therapist training and characteristics [Dissertation]. Ames: Iowa State University; 2019.

Neill EL. Therapists’ experiences with eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR). Iowa: Ames; 2016.

Gomez AM. Thought kits for kids [Internet]. Ana M. Gomez. 2020 [cited 2020 Jan 30]. Available from: https://www.anagomez.org

Solomon RM, Shapiro F. EMDR and the adaptive information processing model: potential mechanisms of change. J EMDR Pract Res. 2008;2(4):315–25.

Shapiro F. Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing: basic principles, protocols, and procedures. New York: Guilford Press; 1995.

Högberg G, Nardo D, Hällström T, Pagani M. Affective psychotherapy in post-traumatic reactions guided by affective neuroscience: memory reconsolidation and play. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2011;4:87–96.

Dudai Y. The neurobiology of consolidations, or, how stable is the engram? Annu Rev Psychol. 2004;55:51–86.

Nader K, Schafe GE, Le Doux JE. Fear memories require protein synthesis in the amygdala for reconsolidation after retrieval. Nature. 2000;406(6797):722–6.

Weems CF, Russell JD, Banks DM, Graham RA, Neill EL, Scott BG. Memories of traumatic events in childhood fade after experiencing similar less stressful events: results from two natural experiments. J Exp Psychol Gen. 2014;143(5):2046–55.

Weisz JR, Krumholz LS, Santucci L, Thomassin K, Ng MY. Shrinking the gap between research and practice: tailoring and testing youth psychotherapies in clinical care contexts. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2015;11:139–63.

Borntrager CF, Chorpita BF, Higa-McMillan CK, Daleiden EL, Starace N. Usual care for trauma-exposed youth: are clinician-reported therapy techniques evidence-based? Child Youth Serv Rev. 2013;35(1):133–41.

Beidas RS, Kendall PC. Training therapists in evidence-based practice: a critical review of studies from a systems-contextual perspective. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2010;17(1):1–30.

Garland AF, Bickman L, Chorpita BF. Change what? Identifying quality improvement targets by investigating usual mental health care. Adm Policy Ment Health Ment Health Serv Res. 2010;37(1–2):15–26.

Holmes SC, Johnson CM, Suvak MK, Sijercic I, Monson CM, Stirman SW. Examining patterns of dose response for clients who do and do not complete cognitive processing therapy. J Anxiety Disord. in press;

Wamser-Nanney R, Scheeringa MS, Weems CF. Early treatment response in children and adolescents receiving CBT for trauma. J Pediatr Psychol. 2016;41(1):128–37.

Chorpita BF, Daleiden EL, Weisz JR. Identifying and selecting the common elements of evidence based interventions: a distillation and matching model. Ment Health Serv Res. 2005;7(1):5–20.

Chorpita BF, Daleiden EL. Mapping evidence-based treatments for children and adolescents: application of the distillation and matching model to 615 treatments from 322 randomized trials. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77(3):566–79.

EMDR Humanitarian Assistance Programs. Answers to training questions. [Internet]. Trauma Recovery: EMDR Humanitarian Assistance Programs. 2017 [cited 2017 Dec 14]. Available from: https://www.emdrhap.org/content/events/answers-to-training-questions/

Becker CB, Zayfert C, Anderson E. A survey of psychologists’ attitudes towards and utilization of exposure therapy for PTSD. Behav Res Ther. 2004;42(3):277–92.

Cook JM, Schnurr PP, Foa EB. Bridging the gap between posttraumatic stress disorder research and clinical practice: the example of exposure therapy. Psychother Theory Res Pract Train. 2004;41(4):374–87.

Foy DW, Kagan B, McDermott C, Leskin G, Sipprelle RC, Paz G. Practical parameters in the use of flooding for treating chronic PTSD. Clin Psychol Psychother. 1996;3(3):169–75.

Whiteside SP, Deacon BJ, Benito K, Stewart E. Factors associated with practitioners’ use of exposure therapy for childhood anxiety disorders. J Anxiety Disord. 2016;40:29–36.

Davis M, Ressler K, Rothbaum BO, Richardson R. Effects of D-cycloserine on extinction: translation from preclinical to clinical work. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60(4):369–75.

Hofmann SG, Meuret AE, Smits JA, Simon NM, Pollack MH, Eisenmenger K, et al. Augmentation of exposure therapy with D-cycloserine for social anxiety disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(3):298–304.

Kushner MG, Kim SW, Donahue C, Thuras P, Adson D, Kotlyar M, et al. D-cycloserine augmented exposure therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62(8):835–8.

Ressler KJ, Rothbaum BO, Tannenbaum L, Anderson P, Graap K, Zimand E, et al. Cognitive enhancers as adjuncts to psychotherapy: use of D-cycloserine in phobic individuals to facilitate extinction of fear. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(11):1136–44.

Andersson E, Hedman E, Enander J, Djurfeldt DR, Ljótsson B, Cervenka S, et al. D-cycloserine vs placebo as adjunct to cognitive behavioral therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder and interaction with antidepressants: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(7):659–67.

Hofmann SG, Smits JA, Rosenfield D, Simon N, Otto MW, Meuret AE, et al. D-Cycloserine as an augmentation strategy with cognitive-behavioral therapy for social anxiety disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(7):751–8.

Alpert J. D-cycloserine augmentation of behavioral therapy for the treatment of anxiety disorders: a meta-analysis. Neuropsychiatry. 2012;2(4).

Ori R, Amos T, Bergman H, Soares-Weiser K, Ipser JC, Stein DJ. Augmentation of cognitive and behavioral therapies (CBT) with d-cycloserine for anxiety and related disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(5).

Rodrigues H, Figueira I, Lopes A, Gonçalves R, Mendlowicz MV, Coutinho ESF, et al. Does D-cycloserine enhance exposure therapy for anxiety disorders in humans? A meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9(7):e93519.

Xia J, Du Y, Han J, Liu G, Wang X. D-cycloserine augmentation in behavioral therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder: a meta-analysis. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2015;9:2101–17.

Otto MW, Kredlow MA, Smits JA, Hofmann SG, Tolin DF, de Kleine RA, et al. Enhancement of psychosocial treatment with d-cycloserine: models, moderators, and future directions. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;80(4):274–83.

• Mataix-Cols D, De La Cruz LF, Monzani B, Rosenfield D, Andersson E, Pérez-Vigil A, et al. D-cycloserine augmentation of exposure-based cognitive behavior therapy for anxiety, obsessive-compulsive, and posttraumatic stress disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(5):501–10 Summary of DCS augmentation trials.

Koopman C, Carrion V, Butler LD, Sudhakar S, Palmer L, Steiner H. Relationships of dissociation and childhood abuse and neglect with heart rate in delinquent adolescents. J Trauma Stress Off Publ Int Soc Trauma Stress Stud. 2004;17(1):47–54.

• Garrett A, Cohen JA, Zack S, Carrion V, Jo B, Blader J, et al. Longitudinal changes in brain function associated with symptom improvement in youth with PTSD. J Psychiatr Res. 2019;114:161–9 Shows the effect of CBT for pediatric PTSD in decreasing activation to emotional faces in the posterior cingulate, mid-cingulate, and hippocampus.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Carl F. Weems and Erin L. Neill declare no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Weems, C.F., Neill, E.L. Empirically Supported Treatment Options for Children and Adolescents with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: Integrating Network Models and Treatment Components. Curr Treat Options Psych 7, 103–119 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40501-020-00206-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40501-020-00206-y