Abstract

Despite deficits in academic outcomes for individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), a relatively small proportion of intervention research has investigated interventions to address academic development for this population. This article includes a review of the research literature on the effectiveness of teaching academic skills to students with ASD using explicit and systematic scripted (ESS) programs. Nine studies were located and evaluated using descriptive analysis and quality indicators for single-case experimental design research. Results showed that only one study met all quality indicators for single-case research and that ESS programs are not evidence-based practices for individuals with ASD, though there is enough promise to warrant additional investigation. Limitations and areas of future research are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Recent estimates indicate the prevalence of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) among school-aged, K-12 students is one in 68 (Baio 2014). Characteristic deficits in social and communication skills of these students often negatively affect their academic success (Knight et al. 2013). Federal legislation in the USA requires all students receive high-quality instruction and have opportunities to learn in general education classrooms, though students with ASD are less likely to receive such instruction compared to their peers with or without other disabilities. For example, the US Department of Education (2009) recently reported participation levels of students with disabilities between 6 and 21 years of age in the general education environment; only 55.7 % of students with ASD participate in general education settings for 50 % or more of their academic day, compared to 82.1 % of students with other developmental delays. Despite this discrepancy, there are very few empirically validated interventions for teaching academic skills to students with ASD (Browder et al. 2008; Browder et al. 2006; Whalon et al. 2009). Academic interventions that better prepare students with ASD to participate in general education settings are needed to mitigate this deficit.

Academic interventions for students with ASD usually involve one-on-one discrete trial instruction or group instruction with students participating sequentially, which does not support acquisition of the skills and behaviors needed to increase access to inclusive environments (e.g., active responding during whole group instruction; e.g., Kamps and Walker 1990; Ledford et al. 2012). Research targeting academic skills for students with ASD has identified promising instructional components, including high rates of accurate responding (e.g., Lamella and Tincani 2012), immediate feedback (e.g., Ranick et al. 2013), carefully sequenced instructional targets (e.g., Knight et al. 2013), predictable instructional formats (e.g., Hume et al. 2012), and interspersed skill instruction (e.g., Volkert et al. 2008). However, translating these components into effective, academic instructional programs can be difficult for schools and teachers, who are more likely to adopt complete programs as opposed to isolated practices (Kasari and Smith 2013).

Published instructional programs that incorporate explicit and systematic procedures in a scripted manner allow consistent implementation across instructors of varying skill levels. Scripted programs control instructional delivery, increasing fidelity of implementation (Cooke et al. 2011). According to Watkins and Slocum (2004), scripts accomplish two goals:

-

1.

To assure that students access instruction that is extremely well designed from the analysis of the content to the specific wording of explanations, and

-

2.

To relieve teachers of the responsibility for designing, field-testing, and refining instruction in every subject that they teach. (p. 42)

Importantly, Cooke et al. (2011) compared scripted to nonscripted explicit instruction and found increased rates of on-task instructional opportunities during scripted instruction. Additionally, students indicated they enjoyed answering together (i.e., in unison) and instructors shared positive outcomes including greater student attention, consistent routine, and reduced likelihood of leaving out crucial concepts. Further, all elected to continuing the program indefinitely.

Historically, explicit and systematic scripted (ESS) instruction within published programs has fallen into two general categories—direct instruction (lower case di) and Direct Instruction (upper case DI). The commonality between the names and procedures, along with a recent increase in the number of programs for both categories, has created some confusion about the parameters of each category. di programs incorporate ESS instruction and generally follow a prescribed format outlined by Rosenshine (1986; i.e., review, presentation, guided practice, corrections and feedback, independent practice, and weekly and monthly reviews). DI programs have traditionally been considered those authored by Siegfried Engelmann and colleagues (e.g., Engelmann and Carnine 2003; Engelmann and Hanner 2008; Engelmann and Osborn 1998). In fact, Engelmann and Colvin (2006) developed a rubric for identifying authentic DI programs, pinpointing seven axioms or principles (i.e., presentation of information, tasks, task chains, exercises, sequences of exercises [tracks], lessons, and organization of content).

Despite this distinction, there has been confusion on the actual differences between di and DI. Watkins (2008) noted di “is a set of teaching practices, and Direct Instruction is a research-based, integrated system of curriculum design and effective instructional delivery based on over 30 years of development” (p. 25). Watkins further reported that the programs developed by Engelmann and colleagues best represent DI suggesting that other programs can also be considered DI. Additionally, the Association for Science in Autism Treatment (see http://www.asatonline.org/treatment/procedures/direct for details) published a definition of DI as follows:

A systematic approach to teaching and maintaining basic academic skills. It involves the use of carefully designed curriculum with detailed sequences of instruction including learning modules that students must master before advancing to the next level. Students are taught individually or in small groups that are made up of students with similar academic skills. Instructors follow a script for presenting materials, requiring frequent responses from students, minimizing errors, and giving positive reinforcement (such as praise) for correct responding.

This definition does not specifically identify program authors or publishers, leaving it ambiguous as to whether di or DI is described. Furthering the confusion, the National Institute for Direct Instruction (NIFDI 2012) lists the programs authored by Engelmann and colleagues as being DI along with non-Engelmann authored programs such as those authored by Carnine, Archer, and others. Thus, to avoid confusion, it seems logical to categorize published programs as explicit and systematic scripted (ESS) programs rather than to attempt to categorize them as di or DI.

ESS programs are typically developed for use with students at three levels of support—primary (general education), secondary (strategic instruction), or tertiary (intensive instruction; Fuchs and Fuchs 2007). Although not necessarily designed for students with ASD, there are many features of such programs that may be effective for teaching academic skills to these individuals. Watkins et al. (2011) described these features as follows:

systematic and planful teaching, a structured learning environment, predictable routines, consistency, and cumulative review. In addition, the programs permit training and supervision of staff to ensure standardized instructional delivery. Instruction is individualized through the use of placement tests to ensure a match between instruction and the child’s assessed needs and ongoing data-based decision making. (p. 306)

Although ESS programs appear to be well suited for students with ASD, the empirical base is not fully understood. Watkins et al. (2011) examined the efficacy of DI with students with ASD. They found no studies that evaluated the effectiveness of DI with a group of students with ASD but did find several studies that included one or more participants with ASD (i.e., Flores and Ganz 2007, 2009; Ganz and Flores 2009). Improved student performance was noted across these studies. It is possible that a broader base of evidence exists for using ESS programs with individuals with ASD, though no research reviews have been conducted on the use of the full range of these programs with this population. A very recent review of evidence-based practices by the National Professional Development Center on Autism Spectrum Disorders (Wong et al. 2013) concluded that a practice termed “direct instruction” fell short of an established evidence-based practice and was instead a “focused intervention practice with some support.” However, this review did not include a description of the range of di and DI or other ESS programs within the category they called direct instruction.

The similarity between instructional procedures used in ESS programs and those described as best practice for children with ASD point to a promising match that could address a long-standing academic deficit with this population. However, the confusion between di and DI has likely limited comprehensive consolidation and review of the extant literature in this area. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to review the research literature on the effectiveness of the full range of published ESS programs (beyond traditional DI) for students with ASD. The specific research questions are as follows:

-

1.

What is the nature of the research base examining ESS curricula with children with ASD?

-

2.

What is the quality of the research base on ESS curricula for children with ASD?

Method

Search Procedures

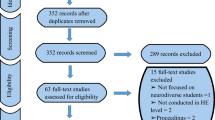

Studies were located using a multi-step search of the literature consisting of (a) an electronic search of four databases: PsycINFO, Education Resources Information Center, PsycARTICLES, ProQuest; (b) a search of the tables of contents (print and online only) of relevant journals; and (c) an ancestral search of the reference lists of articles included in this review. The databases were searched with the Boolean terms (autis*) or (ASD) or (Asperger*) or (developmental disability) or (developmental delay*) or (pervasive developmental delay) or (PDD) and (direct instruction) or (Direct Instruction) or (scripted instruction) or (explicit instruction) or (systematic instruction). The search was restricted to articles written in English and between the years of 1970 and 2013 in peer-reviewed journals. Tables of contents of relevant journals were searched using the following criteria for inclusion of an article for additional review: (1) the title must include the term autism or developmental disability; (2) the title must include a reference to direct, explicit, systematic, or scripted instruction; and (3) the title must not indicate the article is a review or meta-analysis. Forty-five manuscripts were located via the database search and table-of-contents search of relevant journals. Each manuscript was then evaluated using the inclusion process and criteria described below.

Inclusion Process and Criteria

The first author reviewed the title, abstract, and method section of each of the 45 manuscripts to assess for the following criteria:

-

1.

Participants had to have an ASD diagnosis. If participants with and without an ASD diagnosis were involved in the study, the data needed to be disaggregated by disability category.

-

2.

The independent variable had to be a published, explicit, and systematic scripted program. Studies that called the independent variable “direct instruction” were excluded if the instructional program was not formally published.

-

3.

The research design had to be experimental or quasi-experimental. Group and single-case design studies were included. Studies had to be published in English in a peer-reviewed journal. There was no restriction on date of publication.

Nine of the 45 studies met the inclusion criteria listed above. The researchers then conducted an ancestral search of the nine included studies by reviewing the titles in reference lists from each study and applying the aforementioned criteria for evaluating article titles. No additional articles were retrieved via ancestral search.

Study Information

The nine studies were summarized based on the following characteristics: participant (e.g., age, gender, assessment information) and setting (e.g., public or private institution, instructor), measures, program and procedures, design, and findings. The first, second, and third authors extracted the relevant information from each study and populated a table (see Table 1); the fifth author checked the accuracy of each cell within the table. All discrepancies were discussed until all authors reached 100 % consensus on the information included within the table.

The quality of each study was also assessed using the seven quality indicators (with 21 subindicators) developed by Horner et al. (2005) to evaluate the rigor of single-case experimental designs. Although not all of the included studies used a single-case experimental design, all used a within-subject design rendering the guidelines established by Horner and colleagues suitable for included studies. Although Kratochwill and colleagues (2013) have established more recent guidelines for evaluating single-case experimental designs, the updated guidelines eliminate articles from inclusion in the review if they do not include a basic method for minimizing threats to internal validity. As such, critical information about the state of other quality indicators (e.g., description of participants) may be lost. A brief description of the quality indicators is shown in Table 2 (see Horner et al. 2005 for a full description).

When assessing each article based on the quality indicators, the second and third authors assessed the extent to which each study met or failed to meet every quality indicator and subindicator (see Table 2). The fourth author completed an independent review. Interrater agreement across subindicators for the nine studies was 94 %. All disagreements were discussed among all authors until consensus was reached on the appropriate classification.

Results

In alignment with our research questions, two sets of analyses were conducted in this review. These analyses included a descriptive analysis of the studies and an assessment of the quality of each.

Descriptive Analysis

Eighteen participants with ASD, 16 male and two female, were reported across the nine studies. Two of the reviewed studies (Flores and Ganz 2007, 2009) included the same two participants with ASD; participants were counted only once for the present analysis. Mean age of the participants was 9.8 years (range = 4.8 to 16 years). Participant functioning level varied, with IQ scores reported for nine participants within one standard deviation of the mean (one participant was above the mean of 100, and eight were below); one participant scored between one to two standard deviations below the mean, six participants scored greater than two standard deviations below the mean, and two had no IQ scores reported. Race/ethnicity was reported in two studies. Thompson et al. (2012) included three African-American participants, and Flores and Ganz (2009) reported one Native American participant (note: this participant was not identified as such in the 2007 study). Four studies (note: Flores and Ganz (2007, 2009) was conducted in the same location during the spring and fall semesters) were conducted in private schools for children with autism and related disorders, four studies were held in a public school setting within a self-contained classroom, and one study was conducted in a university psychology clinic.

Most studies (n = 7) focused on dependent measures related to language or literacy instruction. Within those studies, four targeted discrete behaviors, such as responding to questions that required an inference or analogy, and three included broad reading outcomes, such as scores on standardized or curriculum-based assessments. The remaining two studies targeted math outcomes, with one (i.e., Thompson et al. 2012) assessing correct written and oral responses when presented with an analog clock or wristwatch, and the other (i.e., Whitby 2013) targeting math word problems answered correctly on a standardized and curriculum-based measure.

The program and procedures for six reviewed studies involved DI programs (i.e., Corrective Reading Comprehension Level A, Language for Learning, Corrective Reading Decoding Level A and B1, and Connecting Math Concepts Level B) administered by an adult instructor; additional ESS programs included the Solve It! Problem Solving Routine Curriculum (adult administered) and the web-based MimioSprout and Headsprout ® Early Reading Programs (same reading program under different parent companies), which were computer administered with adult support. Five studies included delivery of complete lessons/episodes within the program, with four studies implementing a component/portion/exercise of a typical, full daily lesson. Four studies completed an entire level/program. Instruction was typically administered daily (n = 7) with two studies administering instruction 3 days per week. Instructional minutes were either not specified, noted as “varied,” or ranged from 16 to 30 min per day with a total intervention length either not specified (n = 6) or ranging from 5 months to 28 weeks.

The majority of studies (n = 6) employed a single-case experimental design, with the remaining three using a form of within-subject repeated measures (n = 1) or pre-post case study analysis (n = 2). Generally speaking, participants demonstrated improved outcomes following lesson/program implementation. In most cases, this improvement involved performance on targeted behaviors, though three studies employed standardized and curriculum-based assessments, which revealed improved posttest scores in general.

Quality Analysis

Table 2 depicts which quality indicator and subindicators were met or not met for each of the reviewed studies. Studies were required to meet all subindicators within a quality indicator in order to meet the requirements for each indicator. One study (i.e., Whitby 2013) met all of the quality indicators identified by Horner et al. (2005). A second study (i.e., Thompson et al. 2012) met six quality indicators, and a third study (i.e., Ganz and Flores 2009) met five quality indicators. The remaining six studies met four or fewer quality indicators. The most common subindicators not met by the studies were repeated measurement during baseline (n = 4), internal validity (n = 4), and change in trend/level (n = 4).

Eight studies met the quality indicator participant and setting; across subindicators, one study did not meet participant description, and one study did not meet setting description. Four studies met the quality indicator dependent variable; across subindicators, two studies did not meet valid and well described, two studies did not meet measured repeatedly, and one study did not meet interobserver agreement. Four studies met the quality indicator independent variable; across subindicators, four studies did not meet description, and one study did not meet overt measurement of IV. Two of the studies met the quality indicator baseline; across subindicators, four studies did not meet repeated measurement and pattern, and three studies did not meet description. Five of the studies met the quality indicator experimental control/internal validity; across subindicators, two studies did not meet three demonstrations of effect, four studies did not meet internal validity, and four studies did not meet change in trend/level. Seven studies met the quality indicator external validity; across the subindicator, two studies did not meet at least three replications across participants, settings, and materials. Finally, seven studies met the quality indicator social validity; across subindicators, seven studies did not meet magnitude of change.

Discussion

The present review identified a handful of research studies examining published ESS programs for children with ASD. A promising feature of the literature published to date is the variability of participants’ severity levels (i.e., range of IQ and language deficits) and ages, targeted dependent variables, type of program used, and facilitators of the intervention. Although a small sample of studies, the range of the literature suggests ESS programs might have broad applicability for children with ASD. However, limitations with the size and quality of the research base must be addressed before any conclusions can be drawn. In the discussion that follows, we describe the research in this area and speak to limitations in the size and quality of existing research with the goal of clarifying important areas for future research and providing guidance to practitioners in need of academic curricula for children with ASD.

Nature of Research on ESS Programs

Our first question sought to describe the extant literature on ESS programs for children with ASD. The descriptive review of the literature revealed diversity among participants, intervention agents, and dependent and independent variables. Participants ranged in age from 4 to 16 years old and with documented IQs of 64 to 107. This variability is somewhat expected as there are a number of published ESS programs explicitly written for students of varying ages and development. The application to individuals on the more severe end of the autism spectrum is important to note, however, as individuals with more severe disabilities often receive inadequate academic instruction and teachers need programs that meet the needs of these diverse learners (Allor et al. 2014). Intervention agents also represented a diverse group in the reviewed studies, with researchers, behavioral therapists, teachers, and parents involved as implementers of various ESS programs. The ability for teachers and parents to implement ESS programs is a positive attribute of these curricula. Feasibility of implementation may be a selling point for school districts and could be enhanced by scripted protocols and computer-based instruction (e.g., Headsprout® Early Reading).

The most commonly used programs targeted language or literacy skills, though two math ESS programs were also examined among the reviewed studies. Student outcomes were generally positive. It is important to note, however, that many of the reviewed studies differed from ESS research with other populations (i.e., non-ASD) in which (a) the complete ESS program was administered to children and (b) standardized assessments were used to evaluate development in the targeted domain (e.g., Kamps and Greenwood 2005; Shippen et al. 2005). Complete implementation of ESS programs to children with ASD, along with careful analysis of necessary modifications, is an important area for future research.

Quality of Research on ESS Programs

Despite the promise of ESS programs, only one of the reviewed studies, Whitby (2013), met all quality indicators for single-case experimental designs (Horner et al. 2005). A quality indicator that was routinely not met in the reviewed studies was that the description of the independent variable was often insufficient for replication. For example, in four studies, researchers discussed using portions of programs or selected exercises but did not provide detailed specifics of which portions or exercises (Flores and Ganz 2007, 2009; Ganz and Flores 2009; Thompson et al. 2012). Thompson et al. (2012) stated that portions of 16 lessons related to telling time in Connecting Math Concepts (CMC) Level B were implemented but did not specifically state which portions from which lessons including the prerequisite skill lessons and reviewed concepts within each skill. This deviation from scripted protocols may be problematic for replication as ESS programs are designed to build upon previously learned skills, teach prerequisite skills, and provide opportunities for maintenance and generalization of skills. It is therefore necessary to describe the independent variable by delineating components included within an instructional session. This information should include placement test information; specific details pertaining to tasks, exercises, or track administered; and the use of program materials such as a published student workbook.

A second issue was a lack of sufficient repeated measures across both baseline and intervention conditions for four of the studies. Three of the four studies (Grindle et al. 2013; Infantino and Hempenstall 2006; and Peterson et al. 2008) utilized a within-subjects design, but involved only a single assessment prior to and following the implementation of an ESS program. The fourth study (Whitcomb et al. 2011) employed a single-case experimental design, but administered too few assessments across baseline and intervention conditions to meet the evidence standards for repeated assessments within conditions (Horner et al. 2005).

Although not a specific problem in terms of quality indicators described by Horner et al. (2005), none of the studies provided a description of procedures used to teach the targeted domain area (e.g., reading, mathematics) to participants prior to the intervention. This omission has direct implications for interpretation of outcomes, as the comparison condition is somewhat unclear. In order to evaluate the outcomes within the context of other methods of instruction, it will be important for researchers to describe if participants (a) received no instruction in the academic area of interest prior to or during baseline, (b) received instruction in the academic area prior to or during baseline but the instruction was replaced with the program or portion of the program under study, or (c) received instruction in the academic area that was combined with the program or portion of the program under study. A more thorough description of “instruction as usual” conditions found prior to implementation of ESS programs as part of research studies will assist in clarifying whether the ESS programs are best used in isolation or in combination with other practices.

Our conclusion is that ESS programs are not evidence-based practices for individuals with ASD, though there is enough promise to warrant additional investigation. Our conclusions are consistent with those of Wong et al. (2013) and Watkins et al. (2011), the latter of whom stated in regard to DI: “While Direct Instruction cannot be considered research-validated for students with ASD, existing research suggests that Direct Instruction may be effective for teaching academic skills to many children with autism spectrum disorders” (p. 305). We make several suggestions below for research needed to determine whether ESS programs can be an effective method of instruction for children with ASD.

Establishing ESS programs as evidence based for students with ASD requires future research that provides clear descriptions of the independent variable including adequate program descriptions, procedural modifications, and component analyses. Clarifying modifications or adaptations to the independent variable is important for scripted or manualized programs to ensure the intervention can be replicated. Relatedly, research examining full ESS program implementation with fidelity would be beneficial in determining whether implementation of the full programs without adaptation or modification leads to gains in learning outcomes.

The use of standardized assessments that have been psychometrically validated, as well as within-program assessments (e.g., mastery tests, workbook exercises, first-time correct responses during lesson delivery), could be added to the often-used “researcher-developed” measures to strengthen inferences that can be made about the efficacy of ESS programs for children with ASD. For example, Flores and Ganz (2007) measured participants’ responses to orally delivered, researcher-developed probes for inferences, use of facts, and analogies. These are component skills associated with reading comprehension deficits among children with ASD (Nation et al. 2006), but the assessments are not able to speak to broad changes in overall reading comprehension. The researcher-developed measures used in many reviewed studies were likely selected as optimal assessments for the program subcomponents examined in a particular investigation; standardized assessments of comprehension may be too broad to detect changes when the interventions are limited to implementing specific portions of programs over short periods of time (e.g., 6 to 8 weeks). Thus, we suggest researcher-developed assessments be used in combination with standardized assessments to fully understand the nature of change following application of ESS programs. Such an approach would also allow for synthesis and comparison across studies with varied ESS programs or length of intervention periods.

The description of participants in relation to specific characteristics of ASD was also limited in the reviewed studies. The method of diagnosis (e.g., medical vs. school-based, assessments administered) was not included in several studies. In addition, many studies did not describe participants’ overall level of functioning and only one study (Peterson et al. 2008) included information about participants’ language skills prior to intervention. Because many children with ASD present expressive and/or receptive language deficits and the nature of many ESS programs require prerequisite language capabilities, specific descriptions of language skills prior to intervention can help determine who may benefit most from exposure to the programs included in this review. Future research must include more detailed information on the participants with ASD, particularly related to current academic or academic-related skills.

Three of the reviewed studies employed either a parent (Infantino and Hempenstall 2006) or classroom teacher (Thompson et al. 2012; Whitcomb et al. 2011) as the intervention agent, with the remaining studies employing a researcher, graduate student, or highly trained behavioral tutor/therapist. Recent guidelines for developing ASD interventions call for incorporating contextual variables, including the planned intervention agent, in early stages of the research process (Dingfelder and Mandell 2011). Given the behavioral supports and instructional modifications necessary in some of the reviewed studies (e.g., Ganz and Flores 2009; Grindle et al. 2013), future research could include a careful evaluation of educator implementation to confirm the presumed feasibility of delivering ESS programs by teachers, instructional assistants, tutors, or parents.

Despite the findings identified in this review, there are potential limitations of the methods used. First, research studies that may have added to the evidence base could have been omitted from the current review based on our inclusion criteria. The boundaries of our review were limited to articles published through 2013; no attempts were made to seek currently in press articles, as such an approach is difficult to complete systematically and ensure all possible studies are included. Also, although ESS programs (specifically, DI programs authored by Engelmann and colleagues) are considered to be effective for students with disabilities (Kinder et al. 2005), the purpose of this review was to determine the effects of ESS programs on the academic skills of students with ASD. Thus, we included only studies that specifically detailed program effects for students with ASD. This limits the research base to only those studies that disaggregate the data based on disability type and potentially overlooks studies that report positive outcomes for students with ASD within larger groups of participants (e.g., Flores et al. 2013; Waldron-Soler et al. 2002).

Second, the present review analyzed all included studies together to determine whether ESS was an effective intervention for teaching academic content areas to children with ASD. It is possible, however, that a specific ESS such as Connecting Math Concepts could be effective for teaching math to children with ASD, but other ESS are not effective in teaching other targeted skills to children with ASD. As an additional research is conducted on ESS programs, it may become beneficial to review and synthesize the evidence to evaluate whether a specific ESS (such as one of the traditional DI programs) can be considered an evidence-based practice. A similar grouping issue arose for the different academic areas with reading/literacy, language, and math targets examined among the reviewed studies and each needing additional research before applying evidence-based criteria to a specific academic area.

Conclusion

In summary, ESS programs offer promise for students with ASD given their design and instructional features. Unfortunately, these programs cannot be considered evidence based until more rigorous and comprehensive research is conducted. Rather than concluding ESS programs should not be used, we urge researchers to continue examining the effectiveness of such programs for this population of students. With continued high-quality research, we may be able to better understand the potential academic outcomes for students with ASD.

References

References marked with an asterisk indicate studies included in the research review

Allor, J. H., Mathes, P. G., Roberts, J. K., Cheatham, J. P., & Otaiba, S. A. (2014). Is scientifically based reading instruction effective for students with below-average IQs? Exceptional Children, 80, 287–306. doi:10.1177/0014402914522208.

Baio, J. (2014). Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years—autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 sites, United States, 2010. Center for Disease Control and Prevention Surveillance Summaries, 63, 1–24. Retrieved from U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/ss/ss6103.pdf.

Browder, D. M., Wakeman, S. Y., Spooner, F., Ahlgrim-Delzell, L., & Algozzine, B. (2006). Research on reading instruction for individuals with significant cognitive disabilities. Exceptional Children, 72, 392–408.

Browder, D. M., Spooner, F., Ahlgrim-Delzell, L., Wakeman, S. Y., & Harris, A. (2008). A meta-analysis on teaching mathematics to students with significant cognitive disabilities. Exceptional Children, 74, 407–432.

Cooke, N. L., Galloway, T. W., Kretlow, A. G., & Helf, S. (2011). Impact of the script in a supplemental reading program on instructional opportunities for student practice of specified skills. The Journal of Special Education, 45, 28–42. doi:10.1177/0022466910361955.

Dingfelder, H. E., & Mandell, D. S. (2011). Bridging the research-to-practice gap in autism intervention: an application of diffusion of innovation theory. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 41, 597–609. doi:10.1007/s10803-010-1081-0.

Engelmann, S., & Carnine, D. (2003). Connecting math concepts: level a (teacher’s presentation book, student material, and teacher’s guide). Columbus: SRA/McGraw-Hill.

Engelmann, S., & Colvin, G. (2006). Rubric for identifying authentic Direct Instruction programs. Retrieved from http://www.zigsite.com/PDFs/rubric.pdf.

Engelmann, S., & Hanner, S. (2008). Reading mastery reading strand level 1 (signature ed.) (teacher’s presentation book, student material, literature guide and teacher’s guide). Columbus: SRA/McGraw-Hill.

Engelmann, S., & Osborn, J. (1998). Language for learning (teacher’s presentation book, student material, and teacher’s guide). Columbus: SRA/McGraw-Hill.

*Flores, M., & Ganz, J. (2007). Effectiveness of Direct Instruction for teaching statement inference, use of facts, and analogies to students with developmental disabilities and reading delays. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 22, 244–251. doi: 10.1177/10883576070220040601.

*Flores, M., & Ganz, J. B. (2009). Direct Instruction on the reading comprehension of students with autism and developmental disabilities. Education and Training in Developmental Disabilities, 41, 39–53.

Flores, M. M., Nelson, C., Hinton, V., Franklin, T. M., Strozier, S. D., Terry, L., & Franklin, S. (2013). Teaching reading comprehension and language skills to students with autism spectrum disorders and developmental disabilities using direct instruction. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 48, 41–48.

Fuchs, L. S., & Fuchs, D. (2007). A model for implementing responsiveness to intervention. TEACHING Exceptional Children, 39, 14–20.

*Ganz, J., & Flores, M. (2009). The effectiveness of Direct Instruction for teaching language to children with autism spectrum disorder. Identifying materials. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 39, 75–83. doi: 10.1007/s10803-008-0602-6.

*Grindle, C. F., Hughes, J. C., Saville, M., Huxley, K., & Hastings, R. P. (2013). Teaching early reading skills to children with autism using Mimiosprout Early Reading. Behavioral Interventions, 28, 203–224. doi: 10.1002/bin.1364.

Horner, R. H., Carr, E. G., Halle, J., McGee, G., Odom, S., & Wolery, M. (2005). The use of single-subject research to identify evidence-based practice in special education. Exceptional Children, 71, 165–179.

Hume, K., Plavnick, J., & Odom, S. L. (2012). Promoting task accuracy and independence in students with autism across educational setting through the use of individual work systems. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42, 2084–2099. doi:10.1007/s10803-012-1457-4.

*Infantino, J., & Hempenstall, K. (2006). Effects of a decoding program on a child with autism spectrum disorder. Australasian Journal of Special Education, 30, 126–144. doi: 10.1080/10300110609409371.

Kamps, D., & Greenwood, C. (2005). Formulating secondary-level reading interventions. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 38, 500–509.

Kamps, D., & Walker, D. (1990). A comparison of instructional arrangements for children with autism served in a public school. Education and Treatment of Children, 13, 197–215.

Kasari, C., & Smith, T. (2013). Interventions in schools for children with autism spectrum disorder: methods and recommendations. Autism, 17, 254–267. doi:10.1177/1362361312470496.

Kinder, D., Kubina, R., & Marchand-Martella, N. E. (2005). Special education and Direct Instruction: an effective combination. Journal of Direct Instruction, 5, 1–36.

Knight, V. F., Spooner, F., Browder, D. M., Smith, B. R., & Wood, C. L. (2013). Using systematic instruction and graphic organizers to teach science concepts to students with autism spectrum disorders and intellectual disability. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 28, 115–126. doi:10.1177/1088357612475301.

Kratochwill, T. R., Hitchcock, J. H., Horner, R. H., Levin, J. R., Odom, S. L., Rindskopf, D. M., & Shadish, W. R. (2013). Single-case intervention research design standards. Remedial and Special Education, 34(1), 26–38. doi:10.1177/0741932512452794.

Lamella, L., & Tincani, M. (2012). Brief wait time to increase response opportunity and correct responding of children with autism spectrum disorder who display challenging behavior. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 24, 559–573. doi:10.1007/s10882-012-9289-x.

Ledford, J. R., Lane, J. D., Elam, K. L., & Wolery, M. (2012). Using response-prompting procedures during small-group direct instruction: outcomes and procedural variations. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 117, 413–434. doi:10.1352/1944-7558-117.5.413.

Nation, K., Clarke, P., Wright, B., & Williams, C. (2006). Patterns of reading ability in children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 36, 911–919. doi:10.1007/s10803-006-0130-1.

National Institute for Direct Instruction. (2012, March). Bibliography of the Direct Instruction curriculum and studies examining its efficacy. Eugene, OR: Author. Retrieved from http://www.nifdi.org/research/di-bibliography-332.

*Peterson, J. L., Marchand-Martella, N. E., & Martella, R. C. (2008). Assessing the effects of Corrective Reading Decoding B1 with a high school student with intellectual and developmental disabilities: A case study. Journal of Direct Instruction, 8, 41–52.

Ranick, J., Persicke, A., Tarbox, J., & Kornack, J. A. (2013). Teaching children with autism to detect and respond to deceptive statements. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 7, 503–508. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2012.12.001.

Rosenshine, B. V. (1986). Synthesis of research on explicit teaching. Educational Leadership, 43, 60–69.

Shippen, M. E., Houchins, D. E., Steventon, C., & Sartor, D. (2005). A comparison of two Direct Instruction reading programs for urban middle school students. Remedial and Special Education, 26, 175–182. doi:10.1177/07419325050260030501.

*Thompson, J. L., Wood, C. L., Test, D. W., & Cease-Cook, J. (2012). Effects of Direct Instruction on time telling by students with autism. Journal of Direct Instruction, 12, 1–12.

United States Department of Education. (2009). Twenty-eighth annual report to Congress on the implementation of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. Washington, D.C.: Author.

Volkert, V. M., Lerman, D. C., Trosclair, N., Addison, L., & Kodak, T. (2008). An exploratory analysis of task-interspersal procedures while teaching object labels to children with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 41, 335–350. doi:10.1901/jaba.2008.41-335.

Waldron-Soler, K. M., Martella, R. C., Marchand-Martella, N., Tso, M., Warner, D., & Miller, D. E. (2002). Effects of a 15-week Language for Learning implementation with children in an integrated preschool. Journal of Direct Instruction, 2, 75–86.

Watkins, C. L. (2008). From DT to DI: using Direct Instruction to teach students with ASD. The ABAI Newsletter, 31(3), 25–29.

Watkins, C. L., & Slocum, T. A. (2004). The components of Direct Instruction. In N. E. Marchand-Martella, T. A. Slocum, & R. C. Martella (Eds.), Introduction to Direct Instruction (pp. 28–65). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Watkins, C. L., Slocum, T. A., & Spencer, T. D. (2011). Direct Instruction: relevance and applications to behavioral autism treatment. In E. A. Mayville & J. A. Mulick (Eds.), Behavioral foundations of effective autism treatment (pp. 297–319). NY: Cornwall-on-Hudson.

Whalon, K. J., Al Otaiba, S., & Delano, M. E. (2009). Evidence-based reading instruction for individuals with autism spectrum disorders. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 24(1), 3–16. doi:10.1177/1088357608328515.

*Whitby, P. J. S. (2013). The effects of Solve It! on the mathematical word problem solving ability of adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 28, 78–88. doi:10.1177/1088357612468764.

*Whitcomb, S. A., Bass, J. D., & Luiselli, J. K. (2011). Effects of a computer-based early reading program (Headsprout®) on word lists and text reading skills in a student with autism. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 23, 491–499. doi: 10.1007/s10882-011-9240-6.

Wong, C., Odom, S. L., Hume, K., Cox, A. W., Fettig, A., Kucharczyk, S., & Schultz, T. R. (2013). Evidence-based practices for children, youth, and young adults with autism spectrum disorder. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina, Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute, Autism Evidence-Based Practice Review Group.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

A Review of Explicit and Systematic Scripted Instructional Programs for Students with Autism Spectrum Disorder

Julie L. Thompson and A. Leah Wood were at UNC-Charlotte when completing the work.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Plavnick, J.B., Marchand-Martella, N.E., Martella, R.C. et al. A Review of Explicit and Systematic Scripted Instructional Programs for Students with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Rev J Autism Dev Disord 2, 55–66 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-014-0036-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-014-0036-3