Abstract

This article reviews the available literature on group-based social skills interventions for adolescents with autism. Forty-four studies were identified that were published in peer-reviewed journals. While each identified treatment utilized a group format, there was significant heterogeneity among the implemented procedures and evaluative methods. Studies were compared on a number of dimensions, and trends in the field were identified. The findings suggest that there is significant evidence for the usefulness of social skills groups as an intervention for adolescents with autism, and the evidence base is rapidly growing. In addition to a summary of the existing literature, recommendations for areas of future research are identified.

Similar content being viewed by others

Research on the developmental progression of individuals with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) has highlighted the persistent difficulties with social interactions and engagement as they enter adolescence and young adulthood (see Schall & McDonough 2010 for a review). Sigman and Ruskin (1999) even go so far as to assert that individuals with ASD are as severely affected by the core symptoms of autism in adolescence as in early childhood due to their rapidly changing social landscape. Schall and McDonough (2010) noted that while adolescents with ASD generally show improvements in basic communication competencies, they continue to exhibit distinct impairment in social communication. Seltzer et al. (2003) studied a large group of adolescents and adults with ASD and found that, while significant improvements occurred in several domains over time, the two areas showing the least improvement with age were the presence of friendships and the presence of circumscribed interests.

Without the appropriate skill set to negotiate complex social situations, adolescents with ASD can unfortunately fall victim to a host of unpleasant consequences. Bullying and victimization rates are much higher for individuals on the autism spectrum in comparison with their typically developing peers (Carter 2009; Little 2001; van Roekel et al. 2010), with evidence of victimization rates up to four times higher among adolescents with ASD. Evidently, these teens’ social and communicative difficulties result in a susceptibility to bullying, and social skills interventions are unmistakably warranted to help prevent this unfortunate outcome. In addition, adolescence is a time when many individuals with ASD begin to experience the devastating effects of other comorbid psychiatric diagnoses, such as depression and anxiety (Ghaziuddin et al. 2002; Kim et al. 2000). A recent study found that 70 % of adolescents with ASD had symptoms consistent with at least one comorbid disorder, and 41 % had two or more comorbid diagnoses (Simonoff et al. 2008). As friendships have consistently been found to be a protective factor against mental health issues (Miller & Ingham 1976), it is reasonable to assume that by helping adolescents with ASD to develop friendships, we may be able to improve not only their ASD symptoms, but their comorbid symptoms as well.

Clearly, there is evidence that continued intervention efforts are needed as individuals with autism navigate their adolescent years. While adolescence has been a historically understudied age range in the ASD literature (Reichow & Volkmar 2009), researchers are beginning to understand the importance of intervention at this critical developmental stage. Of the thirty-two autism treatments examined within the National Standards Project (National Autism Center 2009), only seven examined effectiveness in adolescents. At the time, social skills training was identified as a treatment with “emerging” effectiveness. An explicit skill training model, particularly in a group context, appears to be a promising avenue for improving social competencies within this population.

The purpose of this systematic review is to summarize and synthesize the available research literature on social skills group interventions for adolescents with ASD.

Methods

Search Procedures

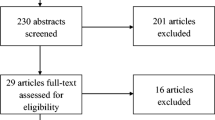

Online searches were conducted within multiple research databases, including PsycINFO, PsycArticles, and Education Resources Information Center (ERIC). The following broad keyword search categories were used (specific search queries included within parentheses): a focus on social skills (i.e., social skills or social competence or social engagement or social interactions or socialization), a group intervention format (i.e., group or intervention or treatment or program), and a focus on individuals with an autism diagnosis (autism or Asperger or ASD or PDD or pervasive developmental disorder). In addition to the initial yield of search results obtained through available databases, additional studies were identified through systematic analysis of the reference lists of articles meeting inclusion criteria.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Search results were required to meet pre-established criteria in order to be included within the current review. Articles were required to be a peer-reviewed original research investigation (not a review/summary article) published in (or translated to) English through August 2013. Next, they needed to describe an intervention procedure (not simply a descriptive study highlighting characteristics or differences between populations). Participants were required to be adolescents with autism (i.e., most of the participants were between the ages of 13–17 and possessed an ASD diagnosis). Because of the focus on group-based interventions, at least three individuals were required to concurrently participate in the same intervention and they could not all be members of a single family. Finally, studies were required to both directly (a) target and (b) measure social competency changes/outcomes. Described procedures were required to include explicit instruction, discussion, and/or practice of social skills/competencies and not just exposure to an ongoing recreational activity and/or general environmental manipulations. Additionally, at least one outcome/dependent measure was required to be directly related to social skills, competence, and/or engagement.

Inter-Rater Reliability of Search Procedures

In order to ensure that all articles were identified correctly, a minimum of two co-authors independently evaluated the merits of each article using an inclusion criteria checklist. Original consensus was reached on 88 % of the articles (44 of the 50 originally identified articles). Initial disagreements were jointly reviewed and analyzed by the authors until 100 % agreement was obtained.

Results

Search Findings

Initial database searches yielded 1,495 peer-reviewed articles. After applying all inclusion criteria to the remaining articles, a total of 44 original investigations were identified that directly targeted social skills in adolescents with ASD in a group format. These studies are summarized in Table 1.

While each identified treatment utilized a group format, there was significant heterogeneity among the implemented procedures and evaluative methods. A number of dimensions served as a means for distinguishing between identified group interventions, including theoretical basis, delivery format, specifically targeted skills, treatment individualization/customization, generalization and maintenance considerations, duration and intensity of treatment, participants per group, inclusion of typically developing peers, the cognitive range of the participants, and intervention context. In addition, differences were noted in the study designs and the methods of assessing change presented in the articles. Each of these important domains is addressed below.

Study Designs

The reviewed investigations vary considerably with regard to research designs. While single-case designs are frequently used in autism research, only a handful of investigations (e.g., Dotson et al. 2010; Mitchell et al. 2010; Webb et al. 2004) used this type of design, which may be attributed to difficulties adopting single-case methods to a group intervention context. Some articles assessed program feasibility characteristics, such as fidelity and consumer satisfaction (e.g., White et al. 2010a), while others used qualitative methods, such as categorizing participant and parent responses to socially relevant inquiries and questionnaires (Fullerton & Coyne 1999; Rose & Anketell 2009). A large proportion of studies (39 %) used a pre-post design to assess treatment effects without a specified control group (e.g., Herbrecht et al. 2009; MacKay et al. 2007; Stichter et al. 2010; Tse et al. 2007). In contrast, a very small number (six of the 44) used a randomized controlled trial (RCT; Laugeson et al. 2012; Laugeson et al. 2009; White et al. 2013) to evaluate treatment effects. Many researchers who opted to study efficacy using uncontrolled or quasi-controlled methods indicated their intention of implementing a RCT after the establishment of initial efficacy and feasibility, following NIMH current research evaluation recommendations (Smith et al. 2007). Additional implementations of carefully controlled RCTs will likely be required to provide clearer evidence of treatment acceptability and effectiveness.

Setting

Many of the studies examined in this review took place in clinic settings (63 %), often associated with large research universities. However, some described investigations evaluated adolescent social skills groups in school settings (Minihan et al. 2011; Williams 1989) and other settings, such as on horseback (Gabriels et al. 2012), at a musical theater company (Corbett et al. 2011), in computer workshops (Wright et al. 2011), and in summer camps (Lopata et al. 2008). While most studies reviewed took place in the USA, several were conducted in other countries, such as Germany (Herbrecht et al. 2009), Scotland (MacKay et al. 2007), Ireland (Minihan et al. 2011; Rose & Anketell 2009), Italy (Valenti et al. 2010), and South Korea (Shin et al. 2012).

Number of Participants per Group

There is an established trend of including groups of four to six participants within a given social skills group paradigm. While not all publications reviewed noted the exact number of participants within each individual group, most fell within this range. This number of participants may be perceived as the ideal balance of group camaraderie and ample opportunities for individual attention, but no studies to date have evaluated the effect of participant numbers on treatment effectiveness.

The Program for the Education and Enrichment of Relational Skills (PEERS) group falls on the higher end of the range with eight to ten participants in each group (Laugeson et al. 2009). The PEERS intervention yielded significant treatment gains immediately following intervention as well as during a 14-week follow-up assessment. These findings suggest that while groups of four to six participants seem to be favored among researchers, it is possible to deliver group interventions to larger numbers of adolescents. However, another factor to consider during group size determinations may be the teaching strategy that will be employed. Specifically, didactic lessons may be easier to scale up for larger groups. Other groups that focus primarily on experiential or activity-based strategies may find that smaller groups allow participants more opportunities for practice and feedback on their use of targeted skills.

Cognitive Level of Participants

All of the articles reviewed described interventions to treat individuals with ASD without intellectual disability. Most studies required a full-scale IQ of 70 or greater for inclusion in the intervention. Only one study reported a slightly lower threshold, with IQs of greater than 50 required, but all participants were still described as “high-functioning” (Mesibov 1984). Herbrect et al. (2009) examined the relationship between a participant’s IQ and response to a group social skills intervention and unsurprisingly found that higher IQ and language ability predicted better response to treatment. It seems that a specific threshold of intellectual capacity is necessary to optimally benefit from the types of group interventions reviewed, but adaptations for those with more limited intellectual functioning should be considered and tested in the future.

Theoretical Basis

While many social skills groups are guided by applied behavior analysis (ABA) principles—reinforcement, shaping, and scaffolding of skills (e.g., Dotson et al. 2010; Stichter et al. 2012; White et al. 2010a) and some were explicitly behaviorally based (Mitchell et al. 2010), many group interventions were also informed by other theories. For example, several existing groups were self-described as using cognitive-behavioral principles (e.g., White et al. 2013), while others were based on theory of mind (Ozonoff & Miller 1995) or psychodynamic perspectives (Tyminski & Moore 2008). However, the majority of social skills group interventions are based in behavioral and cognitive-behavioral principles.

Delivery Formats

The format of intervention delivery varied significantly among identified studies. Some studies, such as Dotson et al.’s (2010) teaching interaction procedure adhered to a set didactic lesson plan, whereas others, such as the group work intervention used by MacKay et al. (2007), use a more activity-based approach. Many groups use a combination of these strategies. For example, Stichter et al. (2010) developed and implemented the Social Competence Intervention (SCI), which addressed social skills through didactics, discussion, modeling, and both structured and naturalistic practice opportunities.

Other teaching strategies used in various groups include modeling (e.g., Laugeson et al. 2012), role-plays (e.g., Tse et al. 2007), rehearsal opportunities (e.g., Minihan et al. 2011), group discussion (e.g., MacKay et al. 2007), video-feedback (Ozonoff & Miller 1995), Social Stories (Broderick et al. 2002), incentive systems (Mitchell et al. 2010), review of videotaped conversations (Fullerton & Coyne 1999), visually presented information (Fullerton & Coyne 1999), interpersonal therapy (Mishna & Muskat 1998), and even art therapy (Epp 2008) and music therapy (Hillier et al. 2012). Of this multitude of teaching strategies, role-play activities were used most frequently and were identified by one researcher as the “most important technique” employed within the intervention paradigm (Mesibov 1984, p. 400).

Only one study compared two different delivery formats: one intended to address social knowledge deficits (Skillstreaming) and the other intended to address social performance deficits (Sociodramatic Affective Relational Intervention; Lerner & Mikami 2012). The authors found that both interventions resulted in improvements in clinician-rated socials skills and reciprocated friendship nominations, but in different ways. The results indicated that participants in the social performance intervention rapidly established friendships within the group, whereas participants in the social knowledge intervention gradually formed these friendships. However, at the conclusion of this brief (4 weeks) intervention, both groups showed equivalent gains in social skills and friendships, suggesting that interventions targeting social knowledge or social performance may have comparable effects on ultimate social competence. Many researchers appear to believe that both methods are useful, as many social skills groups incorporate both didactic and practice opportunities.

Intervention Duration and Intensity

Research has not reached consensus on the amount and intensity of treatment necessary to obtain clinically significant skill gains, as multiple factors affect intervention efficacy. However, almost half of the investigations identified by this review (46 %) described groups that held weekly sessions for approximately 10–16 weeks, with each session lasting approximately 40 min to 2 hours (e.g., Laugeson et al. 2012; McMahon et al. 2013; Stichter et al. 2012).

Investigations examining short-term social skills interventions (<10 weekly sessions) have yielded limited evidence of effectiveness. One study examining two different social skills group interventions found statistically significant results (based on unblinded interventionist ratings on the SSRS-Teacher Survey) after 90 min of treatment every week for 4 weeks (Lerner & Mikami 2012). However, the researchers acknowledged the inherent limitations of such unblended measures and noted that the skill growth observed by the treatment providers was not reported by parents on the SSRS-Parent Survey, thus concluding that interventions of longer duration were likely necessary to produce generalized gains.

Similarly, Rose and Anketell (2009) reported on a pilot social skills intervention that was delivered through 1-hour weekly sessions over 5 weeks. Preliminary qualitative information about the usefulness of the intervention was gathered using non-standardized parent questionnaires, but no standardized data was collected to support the efficacy of the intervention. These researchers concluded that ongoing research was likely needed to support the use of this brief intervention. Likewise, an 8-week intervention conducted by Barnhill et al. (2002) resulted in parent and participant endorsements of new friendships among group members, but no statistically significant results on standardized measures of emotion recognition or paralanguage skills.

Studies with longer-term implementation (>10 weekly sessions) were associated with a greater likelihood of significant treatment gains. For example, a 12-week intervention adapted from the Skillstreaming curriculum resulted in significant outcomes with moderate effect sizes (Tse et al. 2007). Similarly, the PEERS curriculum has strong evidence of treatment effectiveness after 12–14 sessions (Laugeson et al. 2009; Laugeson et al. 2012). Many other interventions of this length or longer periods have also found similarly positive results (e.g., Minihan et al. 2011; Mitchell et al. 2010; Stichter et al. 2012). The available evidence seems to indicate that several months of weekly group intervention may serve as a minimum threshold to reliably improve participants’ levels of social competence.

An intensive social skills curriculum was noted in a summer program implemented by Lopata et al. (2008). Lopata’s summer treatment program took place for 6 hours per day, 5 days per week over 6 weeks, resulting in a total intervention duration of 180 hours, much higher than any other studies reported. Moderately large effect sizes were reported on both parent and staff ratings (up to d = 0.59) after intervention. While these data are very encouraging, there were noted limitations regarding the lack of blind raters or a no-treatment comparison group.

As an alternative to a set number of group sessions, Tyminski and Moore (2008) implemented a group intervention during which students “graduated” at different rates depending on individual progress. The length of intervention ranged from 4 months to 3 years, with an average duration of 14 months. The results of the study indicated that length of intervention had no impact on outcomes, suggesting that the majority of improvement likely occurred early on in treatment.

Individualization/Customization

While most studies reviewed remained limited to the group curriculum, a large proportion of the included studies (41 %) identified individual target skills for participants and incorporated these into treatment. For example, Mitchell et al. (2010) identified three to five target skills for each participant based on their parent’s responses to the Social Skills Rating System (SSRS; Gresham & Elliott 1990) with corroboration from direct behavioral observations. These skills were then embedded into the pre-determined curriculum.

As an alternative means of curriculum adaptation, Minihan et al. (2011) described an intervention in which the content of group lessons were dictated by parental responses to the Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS; Constantino & Gruber 2005). Based on the SRS, a list of the high priority skills for each participant was combined and used to develop the corresponding group curriculum.

White et al. (2010b) used both (a) individual treatment plans and (b) customized group modules. Fifteen modules were available to each group, but the thirteen identified as most applicable in a particular intervention cycle were selected to tailor the content of the group sessions to the specific needs of participants. The researchers identified this strategy as a method to adhere to a manual-based intervention while retaining sufficient flexibility to meet the specific needs of each individual.

Lopata et al. (2008) also described the selection of three or four unique target skills for each child, unrelated to the group curriculum. While all participants in this study received feedback on their target skills, those that were randomized to a response-cost condition earned and lost points based on the use of these specific skills. These points were individually redeemed for edible reinforcers and summed across group members to earn larger incentives (e.g., field trips). These investigators found no significant difference between feedback conditions, but found an overall positive effect for the general intervention package. It is conceivable that individual target behaviors are useful during group interventions, but the way in which participants receive feedback on these target behaviors is less important.

Interestingly, one of the first published articles on group social skills intervention (Mesibov 1984) employed an individualized component. This intervention consisted of weekly 60-min group meetings that were preceded by 30-min individual meetings for each client, allowing for one-on-one teaching to be paired with group practice. A growing number of empirical investigations are incorporating individualization components into their curriculum, which may indicate that there is a unique therapeutic benefit to customizing procedures when working with a diverse range of participants.

Inclusion of Typically Developing Peers

Peer-mediated interventions have gained popularity in recent years, with some researchers actively incorporating typical peers into adolescent social skills groups. While no reviewed investigations reported the inclusion of typically developing peers prior to 2004, a number of more recent studies have reported use of this technology (starting with Carter et al. 2004). The majority of the groups identified by this review remain populated solely by teenagers with ASD. However, roughly a third (30 %) also included typically developing peers. Some, like the Multimodal Anxiety and Social Skills Intervention (MASSI; White et al. 2013) and the consultation model implemented by Minihan et al. (2011) have successfully included typically developing peers with promising results. When peers are involved in group interventions, they are typically trained beforehand and then participate in the groups as social models—providing opportunities for social interaction and peer feedback. Occasionally, peers have been incorporated in different ways. For example, Broderick et al. (2002) described a pilot project in which adolescents concurrently attended a social skills group and a local youth club as a supplemental experience. While no peer models were included in the intervention group itself, every client had weekly scheduled interactions with typical peers during their youth club attendance. Preliminary data reflected possible gains in self-esteem among participants with ASD.

Target Skills

The identified empirical studies also varied with regard to specific skills targeted by the intervention. Most of these investigations targeted global social competence, but some focused on a specific area, such as social cognition (Stichter et al. 2012), theory of mind skills (Ozonoff & Miller 1995), conversational skills (Dotson et al. 2010), emotional expressiveness (Tyminski & Moore 2008), social and emotional perspective taking (MacKay et al. 2007), understanding nonverbal communication (Barnhill et al. 2002), and self-determination (Fullerton & Coyne 1999). More than a few studies specifically targeted anxiety symptoms in conjunction with social skills (e.g., White et al. 2013).

Dependent Variables of Social Change

The intervention approaches covered in this review used a wide variety of dependent/outcome measures to assess the extent to which social improvements had indeed occurred. Most studies (73 %) used parent report questionnaires as an outcome measure. Parent measures that were most frequently used included the Social Skills Rating System (SSRS) and the Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS). In addition, some studies used adolescent report questionnaires and/or direct assessments, such as the Diagnostic Analysis of Nonverbal Accuracy (DANVA2). Interestingly, one study compared responses between parents and participants and found that while participants consistently rated their social skills/competence higher that their parents rated them (both before and after intervention), there was a significant positive correlation between the parent and participant ratings (MacKay et al. 2007). This suggests that participant self-report scores may be elevated but generally follow the same intervention trends as corresponding parent ratings. In contrast, however, Tse et al. (2007) found that adolescents reported greater improvements following a group intervention than their parents. Due to these conflicting results, it may be beneficial to continue examining social skill endorsement discrepancies that exist between parent and child.

In addition to parent and adolescent questionnaires, some studies examined results from interventionist ratings (which may be prone to biased endorsements) and teacher ratings (which have poor return rates). A few articles reported the use of ratings by blinded clinicians (e.g., Herbrecht et al. 2009; White et al. 2013), which represents one of the most rigorous forms of evaluation, as they are completed by experts unaware of the treatment status of participants.

A few studies examined direct, observable data from participants. McMahon et al. (2013) examined behavioral data from the group sessions themselves, documenting increases in the number of responding vocalizations made by group members. Similarly, Mitchell et al. (2010) conducted behavioral probes during training sessions and observed increases in the participants’ target skills, which included operationally defined introductions, initiated conversations, problem-solving skills, and group-joining skills. As a limitation, most of the studies that examined behavioral data collected it solely during the social skill group sessions. For example, Dotson et al. (2010) measured behavioral change during group sessions and also collected generalization data during these group sessions (i.e., participants engaged in brief side conversations with a typical peer who was also involved in the weekly group).

One study was identified that collected behavioral social data outside of the group sessions. Mitchell et al. (2010) gathered generalization data by creating natural opportunities for social probes in alternative locations within the same building, with people who were unrelated to the participant or the study. While this represents progress in the objective behavioral measurement of generalization, there is substantial room for improvement. In the future, researchers may increasingly consider using behaviorally based social probes conducted more distally from the site of intervention and, importantly, using interaction partners who are unknown to participants and of a similar age.

Generalization and Maintenance Techniques

While most of the identified studies primarily focused on immediate treatment effects, more recent investigations have also attended to generalization and maintenance considerations. Assessing whether skills gains are (a) appropriately generalizing to other settings and (b) maintaining beyond the duration of treatment are arguably the most important considerations in any intervention research (Stokes and Baer 1977). Specific techniques have been incorporated into existing projects to promote generalization and maintenance. For example, many interventions include follow-up homework assignments (e.g., McMahon et al. 2013). While homework assignments vary between interventions, they generally involve in-home or community practice of the skill(s) addressed in the group session. Some studies required comprehensive homework assignments consisting of both (a) skill practice guidelines and (b) written responses to socially relevant questions (Mitchell et al. 2010). In addition, these researchers implemented an incentive system to encourage consistent homework completion. Homework assignments have been described as “key” to obtaining generalization of skills by Frankel et al. (2010), as they encourage application of core socialization techniques outside of the time-limited context of each group session.

Another strategy intended to promote generalization and maintenance of skills is the inclusion of a parent component. Parents who are either directly involved in the treatment or informed about the skills being targeted may be in a better position to assist their child in accurate use of these skills outside of the group, thereby leading to widespread, generalized use. Laugeson et al. (2009, 2012) evaluated the Program for the Education and Enrichment of Relational Skills (PEERS) program, which included both homework and parent components. Specifically, a concurrent parent group was conducted alongside the adolescent group, in which parents were provided with education and information about the same skill curriculum as their children. These studies found significant changes to social functioning that maintained after treatment. Generalization measures (completed by teachers) were also significant 14 weeks after intervention, providing evidence of both generalization and maintenance of the skills learned during the initial PEERS intervention.

Other researchers have incorporated parents into the treatment in different ways. For example, Mitchell et al. (2010) conducted parent education sessions every 3 weeks of their 12-week adolescent group intervention. These parent-oriented sessions consisted of psychoeducation, instruction of pragmatic strategies to enhance and generalize their child’s target social skills, and review of video recordings from the group sessions to illustrate behavioral strategies to use at home. In another study, parents met with the group leaders three times over the course of the 11-month intervention to exchange information related to intervention progress and current difficulties (Herbrecht et al. 2009). Several articles indicated the need to increase parent participation within the intervention process, with several proposing future inclusion of parent training components (e.g., Corbett et al. 2011; Tse et al. 2007).

In addition to home practice and parent feedback meetings, MacKay et al. (2007) reported using community outings as a generalization technique. These researchers suggested that outings provided participants with opportunities to practice their skills in a naturalistic setting, and they found statistically significant results on all outcome measures. Across multiple investigations, there is a growing consensus that the ultimate goal of treatment must focus on generalization considerations.

Discussion

There is a rapidly growing evidence base for group interventions that promote social skills in adolescents with ASD. While this population has historically received less research attention, the field has rapidly expanded in response to the critical socialization needs of these individuals.

Findings from this review indicate several key themes and trends across social skills groups. Most of the articles identified in this review evaluated program effectiveness using a pre-post design. However, researchers appear to be transitioning from these preliminary feasibility studies to more rigorously controlled trials, with several RCTs having been conducted and published in recent years (e.g., Laugeson et al. 2012; Lerner & Mikami 2012; White et al. 2013). With regard to treatment setting, most of the studies examined in this review took place in clinic settings, but a small number of studies suggest that social skills groups may be effective in school and community settings (e.g., Barnhill et al. 2002; Kempe & Tissot 2012). The majority of studies were conducted in the USA, but with a growing number of articles describing international participants and projects (e.g., Herbrecht et al. 2009), which provide preliminary evidence for the generalizability of this form of intervention to a variety of cultures and contexts.

Presently, no studies were identified that assessed the relative merit of smaller versus larger groups of participants. However, smaller groups of four to six participants (e.g., Epp 2008; Stichter et al. 2010; White et al. 2013) appear to be the current preference, likely because they allow the researchers a logically manageable group, with the flexibility to conduct both experiential and practice-based techniques. There is, however, evidence that larger groups may be feasible, particularly when delivering didactic lessons (e.g., Laugeson et al. 2012). In terms of participant characteristics, this review did not identify any studies that evaluated social skills group efficacy for individuals with co-occurring intellectual disability, and the findings from several studies seem indicative of certain cognitive prerequisites to adequately benefit from the described programs. However, adaptations for individuals with more limited intellectual capacities will undoubtedly need empirical examination in the future.

The majority of groups reviewed were theoretically based in broad behavioral or cognitive-behavioral principles (e.g., White et al. 2013), although a number of group interventions were based on theory of mind and other theoretical orientations (e.g., Begeer et al. 2010; Ozonoff & Miller 1995). While the various delivery formats implemented in each study initially appear to be very unique, most interventions include some combination of didactic teaching and experiential components (e.g., group discussion and/or rehearsal opportunities). Role-plays were specifically identified as a common and useful treatment technique. In terms of social competencies, most of the reviewed interventions targeted social skills comprehensively, while a smaller number of studies identified a more specific aspect of social competence, such as social cognition or nonverbal communication (e.g., Barnhill et al. 2002). A number of studies targeted anxiety symptoms in addition to social skills (e.g., White et al. 2010a; White et al. 2013), suggesting that the performance deficits associated with co-occurring anxiety symptoms are a core intervention consideration. Mood symptoms, and specifically how these traits interact with social performance, must be considered when developing future interventions for adolescents on the spectrum.

Currently, social skills program treatment intensity ranges from 6 hours up to 180 hours of total intervention, with the majority of programs taking place weekly for 10–16 weeks. The available evidence appears to indicate that several months of weekly group intervention is the minimum amount necessary to reliably improve participants’ social skills. Treatments of shorter duration yielded more limited evidence of social gains and generalization of these skills (e.g., Barnhill et al. 2002; Rose & Anketell 2009), while treatments of a significantly longer duration do not yet use proper assessment methods and/or present compelling data to support prolonged participation in these programs (e.g., Tyminski & Moore 2008). Researchers may wish to empirically examine the benefits of continued participation in groups beyond the typical 10–16-week range to determine whether ongoing participation leads to measurable social competence gains.

A trend toward providing a degree of programmatic flexibility and customization within the group curriculum was noted among many of the reviewed investigations. Individualization was achieved in a variety of ways, including treatment plans or target behaviors unique to each participant or customization of the broader group topics based on individual participant needs (e.g., Lopata et al. 2008; Minihan et al. 2011; Rose & Anketell 2009). These modifications allow researchers and clinicians to (a) target a large number of participants through the use of a group intervention and also (b) address the areas of greatest need for each individual. This blend of group and individual treatment optimizes the efficient delivery of services and may become a strategy used more and more widely in the current era of managed health-care restrictions.

The use of generalization and maintenance techniques also differed between interventions. Some common techniques included homework assignments and varying degrees of parental and peer involvement. Of particular importance, an emerging trend was noted toward the incorporation of typically developing peers into the group interventions in recent years (e.g., Corbett et al. 2011; Dotson et al. 2010; Mackay et al. 2007). Peer-mediated treatment strategies appear to be growing in both popularity and associated research evidence, with this component increasingly changing the landscape of social skills groups. Positive findings from these investigations indicate that researchers may wish to consider including typically developing peers as models and facilitators in group interventions.

Presently, the literature suggests that social skills group interventions can be effective. Efficacy has been measured through a variety of means and most commonly through parent report measures (e.g., Gabriels et al. 2012; Shin et al. 2011; Valenti et al. 2010). Very few studies reported the use of rigorous measurement techniques such as blinded clinician ratings or objectively coded naturalistic behavioral observations (e.g., Koegel et al. 2012; McMahon et al. 2013). As the initial efficacy results indicate the usefulness of social skills groups for adolescents with ASD, these more advanced measurements of change are suggested for use in the next wave of intervention studies. Lastly, as is evident from the great heterogeneity in intervention components described above, next steps for researchers will necessarily include comparing treatments and intervention components to find which aspects are most helpful for this population.

In summary, the research evidence in favor of social skills groups as a valuable intervention for adolescents with ASD is growing larger and larger. As the field expands, the use of more and more complex research methods and measurements is encouraged to allow for a more nuanced understanding of the most promising treatment components, duration, size, and curriculum-based decisions. In addition, a number of new technologies have been identified for use in social skills groups and the use of these practices (e.g., peer models, role-plays, individualization) has yielded promising outcomes. Further manualization of effective treatment procedures, along with independent replications of promising delivery models, is also needed to propel the field forward. Overall, there is a rapidly growing evidence base supporting the use of novel socialization procedures for adolescents with ASD. It is anticipated that empirical investigations will continue to improve in both number and experimental rigor as the field continues to address the complex needs of this growing population.

References

Barnhill, G. P., Tapscott Cook, K., Tebbenkamp, K., & Smith Myles, B. (2002). The effectiveness of social skills intervention targeting nonverbal communication for adolescents with Asperger syndrome and related pervasive developmental delays. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 17(2), 112–118. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/10883576020170020601

Begeer, S., Gevers, C., Clifford, P., Verhoeve, M., Kat, K., Hoddenbach, E., & Boer, F. (2010). Theory of mind training in children with autism: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 41(8), 997–1006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10803-010-1121-9

Broderick, C., Caswell, R., Gregory, S., Marzolini, S., & Wilson, O. (2002). ‘Can I join the Club?’. A social integration scheme for adolescents with Asperger syndrome. Autism, 6(4), 427–431. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1362361302006004008

Carter, C., Meckes, L., Pritchard, L., Swensen, S., Wittman, P. P., & Velde, B. (2004). The Friendship Club: an after-school program for children with Asperger syndrome. Family & Community Health: The Journal of Health Promotion & Maintenance, 27(2), 143–150.

Carter, S. (2009). Bullying of students with Asperger syndrome. Issues in Comprehensive Pediatric Nursing, 32(3), 145–154. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01460860903062782

Constantino, J. N., & Gruber, C. P. (2005). Social Responsiveness Scale. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services.

Corbett, B. A., Gunther, J. R., Comins, D., Price, J., Ryan, N., Simon, D., & Rios, T. (2011). Brief report: theatre as therapy for children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 41(4), 505–511.

Dotson, W. H., Leaf, J. B., Sheldon, J. B., & Sherman, J. A. (2010). Group teaching of conversational skills to adolescents on the autism spectrum. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 4(2), 199-209. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2009.09.005

Epp, K. M. (2008). Outcome-based evaluation of a social skills program using art therapy and group therapy for children on the autism spectrum. Children & Schools , 30(1), 27–36.

Frankel, F., Myatt, R., Sugar, C., Whitham, C., Gorospe, C. M., & Laugeson, E. (2010). A randomized controlled study of parent-assisted children’s friendship training with children having autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40(7), 827–842. doi:10.1007/s10803-009-0932-z.

Fullerton, A., & Coyne, P. (1999). Developing skills and concepts for self-determination in young adults with autism. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 14(1), 42–52. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/108835769901400106

Gabriels, R. L., Agnew, J. A., Holt, K. D., Shoffner, A., Zhaoxing, P., Ruzzano, S., . . . Mesibov, G. (2012). Pilot study measuring the effects of therapeutic horseback riding on school-age children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 6(2), 578–588. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2011.09.007

Ghaziuddin, M., Ghaziuddin, N., & Greden, J. (2002). Depression in persons with autism: implications for research and clinical care. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 32(4), 299–306. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1016330802348

Gresham, F. M., & Elliott, S. N. (1990). Social Skills Rating System. Circle Pines, MN: AGS.

Herbrecht, E., Poustka, F., Birnkammer, S., Duketis, E., Schlitt, S., Schmoetzer, G., & Boelte, S. (2009). Pilot evaluation of the Frankfurt Social Skills Training for children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 18(6), 327–335. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00787-008-0734-4

Hillier, A., Greher, G., Poto, N., & Dougherty, M. (2012). Positive outcomes following participation in a music intervention for adolescents and young adults on the autism spectrum. Psychology of Music, 40(2), 201–215. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0305735610386837

Jepsen, R. H., & VonThaden, K. (2002). The effect of cognitive education on the performance of students with neurological developmental disabilities. NeuroRehabilitation, 17(3), 201–209.

Kempe, A., & Tissot, C. (2012). The use of drama to teach social skills in a special school setting for students with autism. Support for Learning, 27(3), 97–102. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9604.2012.01526.x

Kim, J. A., Szatmari, P., Bryson, S. E., Streiner, D. L., & Wilson, F. J. (2000). The prevalence of anxiety and mood problems among children with autism and Asperger syndrome. Autism, 4(2), 117–132. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1362361300004002002

Koegel, L. K., Vernon, T. W., Koegel, R. L., Koegel, B. L., & Paulin, A. W. (2012). Improving social engagement and initiations between children with autism spectrum disorder and their peers in inclusive settings. Journal of Positive Behavior Support, 14(4), 220–227. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1098300712437042

Laugeson, E. A., Frankel, F., Gantman, A., Dillon, A. R., & Mogil, C. (2012). Evidence-based social skills training for adolescents with autism spectrum disorders: the UCLA PEERS program. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42(6), 1025–1036. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10803-011-1339-1

Laugeson, E. A., Frankel, F., Mogil, C., & Dillon, A. R. (2009). Parent-assisted social skills training to improve friendships in teens with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 39(4), 596–606. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10803-008-0664-5

Lerner, M. D., & Mikami, A. Y. (2012). A preliminary randomized controlled trial of two social skills interventions for youth with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 27(3), 147–157. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1088357612450613

Lerner, M. D., Mikami, A. Y., & Levine, K. (2011). Socio-dramatic affective-relational intervention for adolescents with Asperger syndrome & high functioning autism: pilot study. Autism, 15(1), 21–42. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1362361309353613

Little, L. (2001). Peer victimization of children with Asperger spectrum disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 40(9), 995–996. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200109000-00007

Lopata, C., Thomeer, M. L., Volker, M. A., & Nida, R. E. (2006). Effectiveness of a cognitive-behavioral treatment on the social behaviors of children with Asperger disorder. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 21(4), 237–244. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/10883576060210040501

Lopata, C., Thomeer, M. L., Volker, M. A., Nida, R. E., & Lee, G. K. (2008). Effectiveness of a manualized summer social treatment program for high-functioning children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38(5), 890–904. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10803-007-0460-7

MacKay, T., Knott, F., & Dunlop, A.-W. (2007). Developing social interaction and understanding in individuals with autism spectrum disorder: a groupwork intervention. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 32(4), 279–290. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13668250701689280

McMahon, C. M., Vismara, L. A., & Solomon, M. (2013). Measuring changes in social behavior during a social skills intervention for higher-functioning children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43(8), 1843–1856. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10803-012-1733-3

Mesibov, G. B. (1984). Social skills training with verbal autistic adolescents and adults: a program model. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 14(4), 395–404. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02409830

Miller, P. M., & Ingham, J. G. (1976). Friends, confidants and symptoms. Social Psychiatry, 11(2), 51–58. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF00578738

Minihan, A., Kinsella, W., & Honan, R. (2011). Social skills training for adolescents with Asperger’s syndrome using a consultation model. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 11(1), 55–69. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-3802.2010.01176.x

Mishna, F., & Muskat, B. (1998). Group therapy for boys with features of Asperger syndrome and concurrent learning disabilities: finding a peer group. Journal of Child and Adolescent Group Therapy, 8(3), 97–114. doi:10.1023/A:1022984118001.

Mitchell, K., Regehr, K., Reaume, J., & Feldman, M. (2010). Group social skills training for adolescents with Asperger syndrome or high functioning autism. Journal on Developmental Disabilities, 16(2), 52–63.

Morrison, L., Kamps, D., Garcia, J., & Parker, D. (2001). Peer mediation and monitoring strategies to improve initiations and social skills for students with autism. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 3(4), 237–250. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/109830070100300405

National Autism Center (2009). National Standards Report. Randolph, MA: National Autism Center.

Ozonoff, S., & Miller, J. N. (1995). Teaching theory of mind: a new approach to social skills training for individuals with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 25(4), 415–433.

Reichow, B., & Volkmar, F. R. (2009). Social skills interventions for individuals with autism: evaluation for evidence-based practices within a best evidence synthesis framework. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40(2), 149–166. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10803-009-0842-0

Rose, R., & Anketell, C. (2009). The benefits of social skills groups for young people with autism apectrum disorder: A Pilot Study. Child Care in Practice, 15(2), 127–144. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13575270802685377

Schall, C. M., & McDonough, J. T. (2010). Autism spectrum disorders in adolescence and early adulthood: characteristics and issues. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 32(2), 81–88.

Seltzer, M. M., Krauss, M. W., Shattuck, P. T., Orsmond, G., Swe, A., & Lord, C. (2003). The symptoms of autism spectrum disorders in adolescence and adulthood. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 33(6), 565–581. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/B:JADD.0000005995.02453.0b

Shin, S., Koh, M.-s., & Yeo, M.-H. (2012). A comparative study of the preliminary effects in the levels of adaptive behaviors: learning program for the development of children with autism (LPDCA). Journal of the International Association of Special Education, 13(1)

Sigman, M., & Ruskin, E. (1999). Continuity and change in the social competence of children with autism, Down syndrome, and developmental delays. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 64(1), 1–139.

Simonoff, E., Pickles, A., Charman, T., Chandler, S., Loucas, T., & Baird, G. (2008). Psychiatric disorders in children with autism spectrum disorders: prevalence, comorbidity, and associated factors in a population-derived sample. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 47(8), 921–929. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/CHI.0b013e318179964f

Smith, T., Scahill, L., Dawson, G., Guthrie, D., Lord, C., Odom, S.;Wagner, A. (2007). Designing research studies on psychosocial interventions in autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37(2), 354–366. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10803-006-0173-3

Stichter, J. P., Herzog, M. J., O'Connor, K. V., & Schmidt, C. (2012). A preliminary examination of a general social outcome measure. Assessment for Effective Intervention, 38(1), 40–52. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1534508412455213

Stichter, J. P., Herzog, M. J., Visovsky, K., Schmidt, C., Randolph, J., Schultz, T., & Gage, N. (2010). Social competence intervention for youth with Asperger syndrome and high-functioning autism: an initial investigation. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40(9), 1067–1079. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10803-010-0959-1

Stokes, T. F., & Baer, D. M. (1977). An implicit technology of generalization. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 10, 349–367. doi:10.1901/jaba.1977.10-349.

Tse, J., Strulovitch, J., Tagalakis, V., Meng, L., & Fombonne, E. (2007). Social skills training for adolescents with Asperger syndrome and high-functioning autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37(10), 1960–1968. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10803-006-0343-3

Tyminski, R. F., & Moore, P. J. (2008). The impact of group psychotherapy on social development in children with pervasive development disorders. International Journal of Group Psychotherapy, 58(3), 363–379. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1521/ijgp.2008.58.3.363

Valenti, M., Cerbo, R., Masedu, F., De Caris, M., & Sorge, G. (2010). Intensive intervention for children and adolescents with autism in a community setting in Italy: A single-group longitudinal study. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 4. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1753-2000-4-23

van Roekel, E., Scholte, R. H. J., & Didden, R. (2010). Bullying among adolescents with autism spectrum disorders: prevalence and perception. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40(1), 63–73. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10803-009-0832-2

Ware, J. N., Ohrt, J. H., & Swank, J. M. (2012). A phenomenological exploration of children’s experiences in a social skills group. The Journal for Specialists in Group Work, 37(2), 133–151. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01933922.2012.663862

Webb, B. J., Miller, S. P., Pierce, T. B., Strawser, S., & Jones, W. (2004). Effects of social skill instruction for high-functioning adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 19(1), 53–62. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/10883576040190010701

White, S. W., Albano, A. M., Johnson, C. R., Kasari, C., Ollendick, T., Klin, A., & Scahill, L. (2010a). Development of a cognitive-behavioral intervention program to treat anxiety and social deficits in teens with high-functioning autism. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 13(1), 77–90.

White, S. W., Koenig, K., & Scahill, L. (2010b). Group social skills instruction for adolescents with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 25(4), 209–219.

White, S. W., Ollendick, T., Albano, A. M., Oswald, D., Johnson, C., Southam-Gerow, M. A., . . . Scahill, L. (2013). Randomized controlled trial: multimodal anxiety and social skill intervention for adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43(2), 382–394. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10803-012-1577-x

White, S. W., Ollendick, T., Scahill, L., Oswald, D., & Albano, A. M. (2009). Preliminary efficacy of a cognitive-behavioral treatment program for anxious youth with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 39(12), 1652–1662. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10803-009-0801-9

Williams, T. I. (1989). A social skills group for autistic children. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 19(1), 143–155. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02212726

Wright, C., Diener, M. L., Dunn, L., Wright, S. D., Linnell, L., Newbold, K., . . . Rafferty, D. (2011). SketchUpTM: a technology tool to facilitate intergenerational family relationships for children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD). Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal, 40(2), 135–149. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1552-3934.2011.02100.x

Wright, S. D., D'Astous, V., Wright, C. A., & Diener, M. L. (2012). Grandparents of grandchildren with autism spectrum disorders (ASD): strengthening relationships through technology activities. Internation Journal of Aging and Human Development, 75(2), 169–184. http://dx.doi.org/10.2190/AG.75.2.d

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Miller, A., Vernon, T., Wu, V. et al. Social Skill Group Interventions for Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorders: a Systematic Review. Rev J Autism Dev Disord 1, 254–265 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-014-0017-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-014-0017-6