Abstract

A systematic review of empirical papers comparing the application of DSM-IV and DSM5 diagnostic criteria for Autism Spectrum Disorders identified 12 papers. The application of DSM5 diagnostic criteria resulted in an approximately one third reduction in Autism Spectrum Disorders. The reduction was approximately two thirds for mild forms of Autism. The implications for practice and research are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

The American Psychiatric Association (2013) published revised diagnostic criteria for autism spectrum disorders (ASD) which involved substantial changes. These changes included (1) elimination of individual categories of ASD, such as autistic disorder, pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specific, and Asperger syndrome; (2) introduction of coding of disorder severity; (3) reduction in the number of symptom domains from three to two by collapsing DSM-IV’s domains of communication and social behavior into one domain; (4) changes in the number of symptoms required for diagnosis in each of the domains; and (5) introduction of a new disorder, social (pragmatic) communication disorder. Although these new criteria have been approved, they were not subject to extensive empirical evaluation prior to development.

Between 2012 and 2013, a number of studies have been reported that appear to demonstrate that DSM5 criteria reduce the diagnosis of ASD, which has raised considerable concern (Tsai and Ghazuiddin 2013); however, there has been no systematic review and synthesis of this literature. Further, it is unclear if this possible reduction of ASD diagnoses will be uniform across all individuals with ASD or whether it will impact certain subgroups of individuals formerly diagnosed with DSM-IV ASD. Therefore, the aim of this paper was to systematically search the literature to locate all current empirical papers comparing DSM-IV and DSM5 criteria for ASD and to synthesize their findings.

Method

Procedure

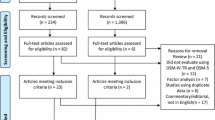

On 24 June 2013, the second author searched PschINFO© using the keywords “Autism” and “DSM 5”. The inclusion criterion was that the article had to compare DSM-IV and DSM5 diagnostic criteria for autism spectrum disorders empirically. Articles that reported sensitivity and specificity, factor analytic studies, reviews, and editorials were excluded. The search identified 995 articles of which 13 studies met inclusion criteria. On 15 July 2013, the second author gathered studies using the terms “Autism AND DSM 5 AND DSM 4” on PschINFO©. The second search identified 436 articles of which 19 articles met inclusion criteria. These searches yielded 32 non-overlapping articles that met inclusion criteria. On 29 July 2013, the second author searched Google Scholar© for all articles that cited these 32 articles that also met the inclusion criteria. This search identified 24 articles that met criteria. These searches yielded 56 non-overlapping articles of which 27 reported data and 29 did not. Finally, the second author categorized the 27 empirical articles into those that (a) directly compared DSM-IV and DSM5 criteria; (b) evaluated the psychometric properties of DSM5 criteria, such as specificity and specificity; and (c) other empirical studies. The study by Huerta et al. (2012) was excluded since although, this study’s abstract reported a reduction of 9 % in the number of child diagnosed with DSM5 autism, the basis for the calculation was unclear. On 6 December 2013, the first author additionally searched PubMed© and Google Scholar© using the terms “Autism” AND “DSM5”. This search located an additional two articles of which one met inclusion criteria. Twelve articles that met the inclusion criterion were retained.

The second author then tabulated features of the retained studies including sample characteristics and methods and instruments used for diagnosis. We distinguished two types of studies. Studies using method 1 compared diagnostic criteria in heterogeneous populations, such as large samples of individuals who may have ASD or clinic samples of individuals who may or may not have a variety of disorders, including ASD who were subsequently evaluated for DSM-IV and DSM5 ASD. Studies using method 2 compared diagnostic criteria in homogenous populations of individuals who had or were very likely to have ASD, such as studies of individuals all of whom met DSM-IV or clinical criteria for ASD who were subsequently evaluated for DSM5 ASD.

The authors then identified or calculated the percentage change in the proportion of individuals who met diagnostic criteria for ASD. The percentage change in the proportion of individuals with ASD was calculated by subtracting the number of individuals with DSM-IV ASD from the number of individuals with DSM5 ASD and expressing it as a percentage of the number of individuals with DSM-IV ASD. Where data were reported for subgroups, such as individuals with autism, pervasive developmental disorders not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS), Asperger syndrome, higher functioning ASD, etc.; the second author also calculated these data separately for each group.

Results

Table 1 displays the methodological features and percentage change in the diagnosis of DSN-IV and DSM5 ASD. The paper included a wide range of ages with participants ranging in age from 17 months to 88 years. Seven studies included children aged 5 or younger and four included participants aged over 21 years. Studies also included the full range of degrees of ASD from individuals at risk for various disorders, PDD-NOS, and autism disorder. The samples were also varied in the degree of intellectual disability (ID) from average intellect to profound ID. Finally, the sample came from a wide range of settings including preschoolers living at home, school, special education, community, and institutional populations. Thus, the samples in these papers were highly varied. Sample sizes were adequate to large ranging from 131 to 5,484 participants. Only one paper (Wilson et al. 2013) used method 1 (heterogeneous sample), and the remaining 11 papers used method 2 (homogenous samples).

The median overall change in diagnosis of ASD from all papers was −36.97 % = (range, −7 to −54 %). When changes were compared between less impaired subgroups (Asperger disorder, high functioning autism, and PDDNOS) and more impaired subgroups (AD, low IQ), there were large differences. The median reductions in the more impaired subgroups were −19.35 % (range, 0 to −26.3 %) and in the less impaired subgroups were −71.27 % (range, −16.6 to −100 %; Table 2).

Discussion

This systematic review of 12 empirical papers comparing the application of DSM-IV and DSM5 diagnostic criteria for ASD found consistent data across studies showing a median reduction of about a third. Reductions were not uniform, but were much smaller in individuals with more severe forms of ASD, but were approximately two thirds for less severe forms of ASD. We can be confident that these findings are robust because they were robust across populations, ages, methods, and researchers. Other data sources confirm that DSM5 criteria exclude individuals with mild forms of ASD. First, Mayes et al. (2014) found that DSM5 criteria were less likely to identify individuals with ASD compared to two psychometric measures and clinical diagnoses of ASD. Second, several studies have found that individuals who meet DSM5 criteria have more severe disabilities than individuals that meet DSM-IV, but not DSM5 criteria for ASD (Matson et al. 2012a; McPartland et al. 2012).

These findings have important implications for services and research. If services apply DSM5 criteria, this may lead to exclusion of many individuals with mild forms of ASD. It is unclear if this will actually happen since practitioners routinely apply diagnoses inaccurately based more on unmet child need than truth (MacMillan et al. 1996). Although practitioners and family members may be eager to diagnostically avoid labels such as ID in preference for more acceptable labels such as specific learning disabilities or emotional disorders, they may be less motivated to avoid diagnostic labels such as ASD, which sometimes give access to better services and are less stigmatizing that other labels. Only future monitoring of patterns of service use will show what may happen.

The American Psychiatric Association partially acknowledged the exclusion of mild forms of ASD when the added rider to the diagnostic criteria was that “Individuals with a well-established DSM-IV diagnosis of autistic disorder, Asperger’s disorder, or pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified should be given the diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder”, but this approach to diagnosis of autism is strange. It enables individuals who previously were diagnosed with ASD to continue to be eligible for services, but results in two odd consequences. First, consider two individuals with identical symptoms who meet DSM-IV criteria for ASD, one of whom was diagnosed before the publication of DSM5 and one diagnosed after: The first will be diagnosed with ASD and eligible for services, but the second will not. The second consequence is that the meaning of the DSM5 term ASD is obfuscated as it refers to different entities using the same term.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, DSM-5 (5th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

Gibbs, V., Aldridge, F., Chandler, F., Witzlsperger, E., & Smith, K. (2012). An exploratory study comparing diagnostic outcomes for autism spectrum disorders under DSM-IV-TR with the proposed DSM-5 revision. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42, 1750–1756.

Huerta, M., Bishop, S. L., Duncan, A., Hus, V., & Lord, C. (2012). Application of DSM-5 criteria for Autism Spectrum Disorder to three samples of children with DSM-IV diagnoses of Pervasive Developmental Disorder. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 169, 1056–1064.

MacMillan, D. L., Gresham, F. M., Siperstein, G. N., & Bocian, K. M. (1996). The labyrinth of IDEA: school decisions on referred students with subaverage general intelligence. American Journal on Mental Retardation, 101, 161–174.

Matson, J. L., Belva, B. C., Horovitz, M., Kozlowski, A. M., & Bamburg, J. W. (2012a). Comparing symptoms of autism spectrum disorders in a developmentally disabled adult population using the current DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria and the proposed DSM-5 diagnostic criteria. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 24, 403–414.

Matson, J. L., Hattier, M., & Williams, L. (2012b). How does relaxing the algorithm for autism affect DSM-V prevalence rates? Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42, 1549–1556.

Matson, J. L., Kozlowski, A. M., Hattier, M., Horovitz, M., & Sipes, M. (2012c). DSM-IV vs DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for toddlers with autism. Developmental Neurorehabilitation, 15, 185–190.

Mattila, M. L., Kielinen, M., Linna, S. L., Jussila, K., Ebeling, H., Bloigu, R., et al. (2011). Autism spectrum disorders according to DSM-IV-TR and comparison with DSM5. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 50, 583–592.

Mayes, S. D., Black, A., & Tierney, C. (2013). DSM-5 under-identifies PDDNOS: diagnostic agreement between the DSM-5, DSM-IV, and checklist for autism spectrum disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 7, 298–306.

Mayes, S. D., Calhoun, S. L., Murray, M. J., Pearl, A., Black, A., & Tierney, C. D. (2014). Final DSM-5 under identifies mild autism spectrum disorder: agreement between the DSM 5, CARS, CASD, and clinical diagnoses. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 8, 68–73.

Mazefsky, C., McPartland, J., Gastgeb, H., & Minshew, N. (2013). Brief report: comparability of DSM-IV and DSM-5 ASD research samples. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43, 1236–1242.

McPartland, J., Reichow, B., & Volkmar, F. (2012). Sensitivity and specificity of proposed DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for autism spectrum disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 51, 368–383.

Rieske, R. D., Matson, J. L., Beighley, J. S., Cervantes, P. E., Goldin, R. L., Jang, J. (2013). Comorbid psychopathology rates in children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorders according to the DSM-IV-TR and the proposed DSM-5. Developmental Neurorehabilitation, 7, 1–6.

Taheri, A., & Perry, A. (2012). Exploring the proposed DSM-5 criteria in a clinical sample. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42, 1810–1817.

Tsai, L. Y., & Ghazuiddin, M. (2013). DSM-5 ASD moves forward into the past. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 44, 321–330.

Wilson, C. E., Gillan, N., Spain, D., Robertson, D., Roberts, G., Murphy, C. M., et al. (2013). Comparison of ICD-10R, DSM-IV-TR and DSM-5 in an adult autism spectrum disorder diagnostic clinic. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43, 2515–2525.

Worley, J., & Matson, J. L. (2012). Comparing symptoms of autism spectrum disorders using the current DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria and the proposed DSM-V diagnostic criteria. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 6, 965–970.

Young, R., & Rodi, M. (2013). Redefining autism spectrum disorder using DSM-5: the implications of the proposed DSM-5 criteria for autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44, 758–765. doi:10.1007/s10803-013-1927-3.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sturmey, P., Dalfern, S. The Effects of DSM5 Autism Diagnostic Criteria on Number of Individuals Diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Systematic Review. Rev J Autism Dev Disord 1, 249–252 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-014-0016-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-014-0016-7