Abstract

This meta-analysis examined studies reporting on randomized controlled trials of the use of cognitive-behavioral approaches to intervention for children with autism spectrum disorder. Ten studies involving 402 children were located. The majority of the participants (mean age of 10.5 years) were high functioning, and all full-scale IQ scores reported for the individual participants were at or above 70. All interventions were administered by therapists in clinical settings, and most targeted anxiety and related issues. There was considerable variation in the intervention components used, the total training hours spent, and the modalities and time span over which the interventions were delivered. A large and statistically significant effect size was obtained from the meta-analysis, and extreme care is required in its interpretation because of substantial heterogeneity. There were some concerns about the use of child and parent reports as outcome measures and the quality of some studies. Further research is needed to investigate the feasibility of cognitive-behavioral approaches for low-functioning children with ASD by teachers in school settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The supports and interventions necessary for children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) are multifaceted and substantial and have considerable economic implication for families, social services systems, healthcare and education systems (Knapp et al. 2009). The need for support and intervention often continues beyond childhood, and outcomes for adults are often poor in many aspects of life, even for most high-functioning children with ASD (Barnhill 2007; Cimera and Cowan 2009). It is therefore essential that interventions for children with ASD should be highly effective, that the effects maintain, and that skills are generalized outside the intervention context.

Interventions for people with ASD are dominated by behavioral approaches with limited considerations of participant cognition. It has been suggested that a wider range of approaches, including interventions with a cognitive approach that address cognitive skills and changes in cognition should be researched to suit the wide diversity of needs of children with ASD (Duffy and Healy 2011; Kasari and Lawton 2010; Luckett et al. 2007). Further, interventions for people with ASD should include a focus on generalization of skills, an area that has long been identified as problematic in learners with ASD (McGee et al. 1983; Rincover and Koegel 1975).

One promising alternative to behavioral approaches for children with ASD is the cognitive-behavioral approach (CBA) (Volker and Lopata 2008; Wang and Spillane 2009). CBA is considered a further development of traditional behavioral strategies integrated with cognitive therapy, having an emphasis on social cognition, and facilitating behavioral changes through cognition (Beck and Fernandez 1998; Dobson and Dozois 2010). CBA has been extensively adopted and is one of the most researched forms of psychotherapy (Butler et al. 2006). When using CBA with typically developing children, therapists focus on the interaction of the learning process, the social environment, and the centrality of information-processing factors (Braswell and Kendall 1988). CBA has been applied successfully to modify children’s impulsive behaviors, to teach academically relevant tasks, as well as to improve problem solving, role taking, and self-control abilities (Little and Kendall 1979; Meichenbaum and Asarnow 1979; Meichenbaum and Goodman 1971).

There have been a number of studies on CBA interventions for adults with ASD; all reported encouraging results and some reported maintenance and generalization of treatment gains, specifically, reduction in social anxiety and in the avoidance of social situations (Cardaciotto and Herbert 2004; Dansey and Peshawaria 2009; Hare 1997; Weiss and Lunsky 2010). In addition, CBA is considered to have the potential to facilitate the generalization of skills in children with ASD (Chalfant et al. 2007; Sofronoff et al. 2007).

People with ASD may have difficulties with cognitive processing such as poor executive functioning, cognitive inflexibility, weak central coherence and impaired theory of mind (Baron-Cohen et al. 1985; Happé and Frith 2006; Hill 2004). Since these cognitive impairments are suggested to be intricately interlinked, interventions that directly address cognition as well as behavior (e.g., CBA interventions) may offer the opportunity for generalized improvement in adaptive functioning (Greig and MacKay 2005; Klinger and Williams 2009).

A number of literature reviews have included CBA interventions for children with ASD. Generally, reviewers have concluded that although there is extremely limited high quality empirical evidence, CBA appeared to be a feasible and effective treatment for specific mental health problems of children with high-functioning ASD. To date, some reviews provided narrative analyses (Anderson and Morris 2006; Donoghue et al. 2011; Moree and Davis 2010; Rotheram-Fuller and MacMullen 2011), some included non CBA interventions (Cappadocia and Weiss 2011; White et al. 2009), and some were limited to specific issues such as interventions for anxiety (Lang et al. 2010). Only two reviews of CBA interventions for children/adolescents with ASD did not restrict the included intervention studies to specific treatment targets (Kincade 2009; White 2004). These two reviews have limitations. Primarily, they were narrative and did not provide a meta-analytic synthesis of the research. Kincade (2009) reviewed 15 published journal articles but did not address important aspects of research design quality. The older White (2004) review included only two randomized controlled trial studies (RCTs). Neither of these two reviews included unpublished reports, with the attendant risk of publication bias. Since the review by Kincade (2009), more relevant CBA research studies have been published and many of them are group design studies which can provide stronger evidence regarding effectiveness (e.g., Drahota et al. 2011; Koning 2010; McNally Keehn 2010; Reaven et al. 2012; Scarpa and Reyes 2011; Sung et al. 2011; Wood et al. 2009a, b).

The present study provides a meta-analytic review of CBA interventions for children and adolescents with ASD. This review considers generalization to other settings and behaviors, as well as long term maintenance of the intervention effects. It includes all relevant RCTs, either in published journal articles or unpublished theses, and includes an analysis of study quality.

In this review, the following research questions are addressed:

-

1.

What are the types and qualities of CBA intervention studies with children having a reported diagnosis of ASD?

-

2.

What are the characteristics of participants and intervention programs?

-

3.

What are the common strategies used in these interventions?

-

4.

What measures are used?

-

5.

Did the treatment effect generalize and maintain?

-

6.

How effective are CBA interventions?

Methodology

A search was conducted of four databases: ERIC, CINAHL, ProQuest, and PsycINFO, in December 2012 using the descriptors “autism,” “autistic,” “Asperger*,” “pervasive developmental disorders-not otherwise specified,” and “PDD-NOS” to describe the population; “cognitive-behavio*,” and “cognitive behavio*” to describe the approach; and “treatment,” “intervention,” “program,” and “training” to describe the nature of the study. A study was included in the initial listing if it met the following criteria:

-

1.

It was a journal article, or a dissertation / thesis at or above master’s degree, or an original study reported in a published book.

-

2.

It was written in English.

-

3.

It was an intervention study that reported outcomes.

-

4.

The author(s) explicitly described the intervention as cognitive-behavioral.

-

5.

The participants in the study were described as adolescents or children with a reported diagnosis of ASD, i.e., autistic disorder, Asperger syndrome, or pervasive developmental disorder-not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS).

-

6.

In the case of studies including participants with and without ASD, outcomes for participants with ASD were reported separately.

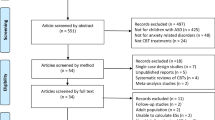

The initial search located 612 papers, 170 from ERIC, 44 from CINAHL, 191 from ProQuest, and 207 from PsycINFO. When duplicates were removed, there were 530 unique reports. All reports were screened by the first and second authors who viewed the report titles and abstracts. A report was excluded when information in its title or abstract unequivocally indicated any of the inclusion criteria were not met. Sixty three reports were reserved after the first-stage screening. Overall agreement for this first-stage screening process was 93.0 %. The third author reviewed reports where the first and second authors disagreed and all disagreements were resolved through discussion between all the authors.

In the second stage, the first and second author independently examined the full text of all the 63 reserved reports to confirm whether they fully met the inclusion criteria. Twenty-six reports were excluded, leaving 37 reports to be included. Overall agreement for this second-stage screening process was 98.4 %. All disagreements were resolved through discussion between all authors. Papers were excluded because the participants were not children (Cardaciotto and Herbert 2004; Hare 1997; Kruzynski 1998; Perry 2008; Weiss and Lunsky 2010; Zelazo 1997), they were not intervention studies reporting on outcomes (Attwood 2004; Barsky 2001; Gratton 2010), the author did not explicitly describe the intervention as cognitive-behavioral (Lerner 2013; Snell 2012), the participants did not have a reported diagnosis of ASD (Fitzgerald and Werner 1996; Grosso 2012), or because they included participants with or without ASD and outcomes for participants with ASD were not reported separately (Epp 2008; Gooding 2010; Kellner and Tutin 1995; Lim et al. 2007). The other excluded reports were either not written in English, did not report on intervention outcomes, or did not use a CBA.

To complete the search, the names of authors of the reports selected were searched in the ERIC and PsycINFO databases. Ancestral searches of the reference lists of all intervention studies and previous reviews in this area were carried out (i.e., Anderson and Morris 2006; Cappadocia and Weiss 2011; Lang et al. 2010; Rotheram-Fuller and MacMullen 2011; White 2004). Two further studies meeting the inclusion criteria were located (Ooi et al. 2008; Vickers 2002). Again, these were independently reviewed by the first and second authors, and it was agreed that both should be included. The final list included 27 articles, 6 theses, and 6 book chapters.

Then, both the first and second authors independently reviewed the methodologies of all the reports shortlisted and classified the research design. Twelve reports, based on ten studies, were identified as RCTs. One thesis and two journal articles reported on the same study (i.e., Drahota 2008; Drahota et al. 2011; Wood et al. 2009a), and were treated as a single study. The agreement for identification of the RCTs was 100 %.

Both the first and second authors independently extracted all the quantitative data (including study quality indicators and intervention components reported by authors for generalization or maintenance), scored the study quality, and coded data of intervention targets. The scoring of study quality indicators was based on criteria as documented in the Scoring Guidelines (see Appendix) and was derived from Gersten et al. (2005) with the maximum possible quality score being 18. For the data on intervention targets, both the first and second author independently coded 30 % of the studies (n = 3 studies). The authors’ agreement was 88.5 % for extracting quantitative data, 78.0 % for scoring study quality, and 87.5 % for coding the intervention targets. All disagreements were resolved through discussion between all the authors.

Following the data extraction, a meta-analysis was performed. Given the variation in the interventions and outcome measures, an a priori decision was made to employ a random effects analysis as recommended by Borenstein et al. (2009). Data were analyzed using the Comprehensive Meta-analysis program (Borenstein et al. 2005). Where multiple CBA intervention groups were compared with a no-treatment control (i.e., Sofronoff et al. 2005), each comparison was treated as a separate study for the purpose of analysis. Therefore, based on nine journal articles and three theses, 11 comparisons were conducted involving 128 effect size (ES) calculations. In calculating ES, the expected direction of change on the measure was first determined, and positive values were allocated to ESs that reflected better performance in the CBA group. Hedges’ g was calculated using pre- and post-test means and pooled post-test standard deviation data where available, or from dichotomous outcomes where reported (events or non-events). In the absence of such data, ES estimates were extracted from t values, means and p values or other available data. In one study (Sung et al. 2011), scores were assigned to the categorical data of severity of anxiety based on Clinical Global Impression Scale (i.e., normal = 1, borderline = 2, mildly ill = 3, moderately ill = 4, and markedly ill = 5), consistent with the original instrument scoring system. The means and standard deviations of these scores were used to calculate the effect sizes. In the same study, the three categories of data reporting participant improvement status (i.e., deteriorated, no change and improved) were resolved into two categories to generate dichotomous outcomes for calculating the effect sizes (i.e., the deteriorated category was combined with the no-change category to form one category of not improved, and the improved category was maintained). ESs were calculated for each outcome variable and time point within a study. Mean ES was calculated across outcome variables and time points in each study using a mixed effect analysis model, thus, confidence intervals are likely to be conservative.

Results

Participants

The reviewed studies enrolled 402 participants (M = 40.2 per study, 199 completed intervention, 173 completed control conditions, 30 dropped out before completion). Participant details are provided in Table 1. All studies specified their participant selection criteria with eight reporting a replicable selection process. The most frequently specified selection criterion was a lower limit on IQ scores.

The selection criteria were reflected in the characteristics of the selected participants. All reported mean IQ scores of study cohorts were above 100, except in one study (mean verbal IQ score = 96.8 in Sung et al. 2011). The overall mean full-scale IQ score was 106.0 and individual IQs ranged from 70 to 139 across the 203 participants with data reported. Most participants were either diagnosed with Asperger syndrome (n = 196, 48.8 %), or described as high functioning with autistic disorder (n = 71, 17.7 %). Others were diagnosed with PDD-NOS (n = 20, 5.0 %) or without sub-type diagnoses (n = 40, 10 %). Although nine studies reported the instruments or protocols for diagnosing ASD, only four provided scores on the level of autistic symptomology. Across all the reviewed studies, participant mean age was 10.5 years (ranged from 4.5 to 16 years) and nine studies included participants aged between 10 and 11 years old. The most frequently reported comorbidity was anxiety disorder. The gender ratio of participants was approximately seven males to one female. Participants in two studies (n = 56, 13.9 %) were using medication.

Study Characteristics and Intervention Features

Study characteristics and intervention features of the ten RCTs are summarized in Table 2. All the reviewed reports were dated between 2005 and 2012. All interventions used a manual or program documentation, and the Coping Cat CBA Program by Kendall and Hedtke (2006a, b) for treating anxiety in typically developing children was used or adopted in three interventions. All interventions were administered by psychologists or therapists in clinical settings and included the involvement of parents and/or peers. In addition to attending intervention sessions, parents also supported their child’s practice of learnt skills outside intervention sessions (six studies), and/or acted as social coaches (four studies). Most interventions were delivered in small groups (seven studies) and a few were delivered individually (three studies).

The time span over which the interventions took place varied from 6 weeks to 6 months (M = 13.7 weeks). All interventions had weekly sessions. While the length of individual sessions varied between 1 and 2 h (M = 97.5 min), the total training hours varied from 8 to 30 h (M = 19.7). The actual hours a therapist spent with each participant during the interventions ranged from 6.7 to 17.5 (M = 10.8 h). There were insufficient data on the therapist hours each parent received as well as hours the therapists/researchers spent in preparing the interventions. No studies reported post intervention follow-up training.

A large number of intervention components were identified and each intervention had a unique combination of intervention components. The mean number of components implemented in the interventions was 10.6. Some components were common across most studies such as practice of skills (ten studies), affective education or training regarding emotion (nine studies), homework assignments (eight studies), relaxation (seven studies), and visual support (seven studies). The three commonly discussed components in CBA literature for the general population and adults with intellectual disabilities were used in some of the reviewed studies (i.e., cognitive restructuring in six studies, problem solving in three studies, and self-instruction in one study) and three studies did not refer to these components at all.

Intervention Outcome Measurement

There were 91 outcome variables measured across studies (M = 9.1 per studies). These variables were used to indicate improvement in eight categories of intervention targets (i.e., anxiety reduction in eight studies, changes in cognition in seven studies, problematic emotions other than anxiety in four studies, problematic behavior other than anxiety-related in three studies, social skills improvement in three studies, parental or teachers’ issues in two studies, other constructs in two studies, and other specific problems in two studies). The most frequently measured target was anxiety (seven studies). While four reports included measures of all stated intervention targets, some intervention targets were seldom measured (i.e., specific problems not measured in the two targeting studies, parental’ or teachers’ issues measured in one targeting study, and other constructs measured in one targeting study). On the other hand, some researchers measured variables not specified as intervention targets (problematic behavior other than anxiety related in one study, problematic emotions other than anxiety in one study, social skills improvement in one study, parental or teachers’ issues in one study, other constructs in one study).

There were five main categories of outcome measures used: standard rating scales or inventory checklists completed by parents, participants, therapists, or teachers measured 59 outcome variables; diagnostic interviews with parents or with both participants and parents measured 16 variables; knowledge or ability tests measured 6 variables; rating scales developed by authors using parent reports measured six variables, and behavior observations measured four variables. The most frequently used measures were standard rating scales or inventory checklists completed by parents (n = 37 outcome variables in 8 studies) and by participants (n = 17 outcome variables in 4 studies). The most frequently used standard measures were the Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale (SCAS) (four studies), the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule (ADIS) (four studies), and the Clinical Global Impression (CGI) (three studies). Only one study did not include parent/participant reports and checked interrater reliability/interobserver agreement on all outcome measures. Three other studies included parent/participant reports in some measures and checked interrater reliability/interobserver agreement on all other measures not using parent/participant reports. All reported reliability was above 80 % except one measure for child behavior observation (interobserver agreement = 76 % in Koning 2010).

Effectiveness of Intervention

There was considerable variation in intervention features and outcome variables across the studies and the appropriateness of reporting an overall summary ES metric was questioned. After consideration, it was decided to report a summary metric along with examination of possible moderators. Hedges’ g was calculated for the ten RCTs based on 11 intervention group and control group comparisons. A forest plot of the meta-analysis is presented in Fig. 1. The relative weighting of studies in the overall estimate is indicated by the size of the squares in the figure. The resulting overall ES of 0.89 was statistically significant (95 % CI [0.50, 1.29]; p < 0.0001). Heterogeneity was significant (Q = 27.77, p = 0.002) and a moderate to high amount of variance was accounted for by between-study heterogeneity (I 2 = 63.99).

Given the level of heterogeneity, six possible moderators (i.e., intervention time span, total training hours, group or individual treatment, parent involvement, research design quality score, and total study quality score) were examined by dichotomizing the studies on each moderator. The detailed ES comparisons of studies dichotomized with these possible moderators are shown in Table 3. All ES comparison results were nonsignificant, indicating that these moderators were not significantly related to ES. This lack of statistical significance was possibly due to the small number of studies and related low statistical power. The comparisons with moderators of intervention time span, total training hours, and group/individual treatment resulted in small ES differences. The comparison with moderators of parent involvement, research design quality score and total study quality score, however, resulted in large ES differences, indicating their potential as moderators.

In addition, three types of outcomes were examined. The overall ES of all outcomes measuring anxiety and anxiety related issues was 1.07 and was statistically significant (95 % CI [0.48, 1.66]; p < 0.001) (in seven studies, with 93 individual ES). The overall ES of all outcomes measuring social skills was 0.98 and was statistically significant (95 % CI [0.47, 1.49]; p < 0.001) (in three studies, with 11 individual ES). The overall ES of all other outcomes was 0.81and was statistically significant (95 % CI [0.25, 1.37]; p = 0.005) (in six studies, with 24 individual ES).

Interventionists using a CBA appear to have assumed that intervention effects would be generalized and maintained by strategies such as parent/teacher involvement and practice, and thus incorporated them. Only some of the reviewed studies specified their intervention components for generalization purposes (seven studies) and none did for maintenance. The specified strategies for generalization were home practice (four studies), parent training and participation in sessions (three studies), school involvement (two studies), and video modeling (one study). Participant behavior changes were measured at home and in contrived social settings in three studies, providing some limited evidence of generalization of skills outside intervention settings. Follow- up measurements on outcomes variables, primarily based on parent reports, were taken at six weeks to six months post intervention in seven studies and mostly indicated that effects were maintained. The social validity of the interventions effect was checked in four studies. The measures used were mainly questionnaires, and all results were positive with high ratings.

In order to evaluate possible publication bias, a funnel plot was constructed with missing studies imputed using the Duval and Tweedie trim-and-fill procedure. The resulting plot is presented in Fig. 2. The plot was asymmetrical and four missing studies were imputed. The adjusted overall random effects ES was 0.58 (95 % CI [0.18, 0.99]). In addition, the classic fail-safe N was 142, indicating that an additional 142 studies with a mean ES of 0 were needed to reduce the overall calculated ES to a non-significant level (α = 0.05). The Orwin fail-safe N was 77, indicating that an additional 77 studies with mean ES of 0 would be needed to reduce overall ES to below a trivial value, set at 0.1.

Study Quality

An acceptable and appropriately documented randomization method was reported in six of the reviewed studies. A participant attrition rate below 10 % in both intervention and control groups was reported in only three studies. Preintervention equivalence of control and comparison groups or adjustments made in data analysis was reported in five studies on all outcome measures and in three studies on some outcomes. Raters were blind to treatment conditions for all measures in one study, and blind for measures not using parent or self-reports in four studies. The remaining five studies used either measures by raters not blind to treatment conditions or reported by parents or participants. Many studies provided clear descriptions of the intervention setting (six studies) and procedural fidelity checking (nine studies), but only a few provided data on procedural fidelity (three studies).

The study quality scores of individual studies are displayed in Table 2. The quality of the reviewed studies varied widely with research design quality scores varying from 25.0 to 75.0 % of the maximum possible score (M = 56.3 %), and total study quality scores from 25.0 to 83.3 % of the maximum possible score (M = 60.6 %). The average study quality score was 58.3 % for published journal articles and 70.4 % for the three doctoral dissertations.

Discussion

The present review examined RCTs on cognitive behavioral interventions for children with ASD. The earliest report located was dated 2005, indicating that development in this research area is relatively recent. Overall, the research studies focused on high-functioning children with ASD aged around 10 years old, were mostly interventions for anxiety, and were restricted to clinical settings with therapists.

Participant Characteristics

It has been suggested that symptoms of ASD might moderate the efficacy of CBA interventions for anxiety of typically developing youth (Puleo and Kendall 2011). However, with limited reports on participant level of autistic symptomology, this review could not examine the moderating effects of the degree of autistic symptomology on intervention outcome. In addition, the focus of the reviewed interventions was on participants within normal range of intellectual ability and around the age of 10 years. This narrow focus did not allow examination of the effects of CBA on children with ASD having intellectual disabilities and/or beyond this narrow age range.

Intervention Features

Other than all interventions being conducted by therapists in clinical settings and nearly all intervention targets being anxiety reduction, the reviewed interventions were heterogeneous in many other important features such as programs used, intervention modalities, time span over which intervention took place, numbers of sessions, total intervention hours, and intervention components. Each reviewed intervention implemented a unique package of multiple components. Based on the currently available information, it is impossible to identify the key components that contributed to the efficacy of the CBA. This difficulty in concluding which components contribute to efficacy has also been noted for multiple component interventions in other fields, such as nursing (Edwards et al. 2006).

All reviewed interventions used program manuals and a few manuals allowed flexibility or adopted a modular approach, by which individual components in the manuals were selected and implemented to meet the specific needs of the participants (Cool Kids in Chalfant et al. 2007; Building Confidence FCBT in Wood et al. 2009a). This flexibility was useful to address individual needs (Kendall et al. 1998), but introduces further variation within individual studies.

Across the interventions, the terminology and descriptions of interventions were often inconsistent. Although both reported on the same study, Drahota (2008) reported the use of behavioral experimentation but Drahota et al. (2011) did not mention behavioral experimentation and reported the use of exposure, which was not mentioned in Drahota (2008). Some studies explicitly reported the use of cognitive restructuring; some used a simplified version of cognitive restructuring (Chalfant et al. 2007); others did not report the use of cognitive restructuring, but reported the use of “thinking tools,” which appeared to be similar (Sofronoff et al. 2005, 2007).

Many intervention components used in the reviewed studies (e.g., practice of skills, homework, visual support, relaxation, and affective education or training regarding emotion) are typical components of interventions for children with ASD, regardless of whether a cognitive framework is used (Attwood 2003; Beaumont and Sofronoff 2008; Groden and LeVasseur 1995; Howlin et al. 1999; National Research Council 2001). On the other hand, some often-discussed CBA components such as cognitive restructuring, self-instruction, and problem solving were not commonly documented/implemented in the reviewed studies (Crawley et al. 2010; Graham 2005; Meichenbaum and Goodman 1971; Scott 2009). The considerable heterogeneity of the interventions, together with the possible absence of consensus in component terminology and description of interventions, do not facilitate the investigation of the underlying mechanisms.

Measurement of Outcome Variables

The outcomes variables in the reviewed studies were mainly severity of anxiety or related issues and were measured with standardized measures. Although behavioral changes were measured in five studies, only three studies provided observational measures of the actual changes in natural or contrived settings.

The majority of the standardized measures (e.g., rating scales and inventory checklists) were completed by either participants’ parents or the participants themselves. In the measurement process, fewer than half of the reviewed studies reported that assessors were blind to participant treatment conditions. Only one study had all outcomes measured by assessors blind to participant condition. With the informants or assessors being aware of participant treatment condition, the outcome data would possibly be at higher risk of bias (Gersten et al. 2005). These issues are of concern when interpreting the improvement indicated for most of the outcome variables measured.

There were additional issues regarding the major informants being the parents and the participants. Discrepancies between their reports were raised in two reviewed studies (i.e., McNally Keehn 2010; Wood et al. 2009a). Some studies examined these discrepancies and found that compared to their parents, high-functioning adolescents with ASD reported more psychiatric symptoms and empathetic features but fewer autistic traits (Hurtig et al. 2009; Johnson et al. 2009). Parents’ reports may be limited when reporting on perceptions of their child’s feelings and emotions. Self-reports on emotions and related cognition might also be unreliable and invalid (Mazefsky et al. 2011). Sofronoff et al. (2005) discarded self-reported data due to the participants’ difficulty with accessing and reporting their own emotions. McNally Keehn (2010) argued that the accuracy of self-reporting on emotions and thoughts by individuals with ASD is questionable because they appear to lack insight into these mental states. Although intervention training might have increased participant awareness of symptoms or understanding of themselves, such measures might be more useful as indicators of change in awareness, rather than actual improvement, in symptoms such as anxiety disorders (Drahota 2008; Reaven et al. 2009). The very few direct observations of behavioral changes, the dependence on standard rating scales completed by parents or participants, and the informants or raters being aware of treatment conditions are all problematic, as is the reliability of self-reports about emotion and cognition.

Efficacy of Interventions

The significant and large ESs (0.89) obtained in the current meta-analysis is suggestive of the overall efficacy of CBA interventions for children with ASD. This finding is primarily applicable to anxiety interventions for children with ASD within the normal range of intellectual abilities and around the age of 10 years. Given, the diversity in intervention components and measured outcomes, the overall summary effect size should be viewed with caution. Further, the interpretation of this result has to be made in the context of the problems with the outcome measures used, the small number of studies reviewed, as well as the quality of the studies. Attempts were made to examine possible moderator variables but the findings were not statistically significant, although the low power of tests and the small number of studies need to be considered in interpreting the findings. Parent involvement, research design quality, and total study quality appeared to be potential moderators with large ES difference between studies dichotomized with these features. Although evidence of publication bias was found, the estimated effect size was only reduced to a medium level after adjustment for imputed missing studies. In addition, given the limited size of the corpus of published research, an implausibly large number of missing studies would be required to reduce the calculated ES to either a trivial or non-significant level.

There appears to be a lack of attention paid to generalizing or maintaining the intervention effects gained. The current data are thus inadequate to demonstrate which strategies are effective for generalization or maintenance. Nonetheless, the few generalization strategies used in the reviewed studies were those suggested in the wider literature for generalization and maintenance, being mainly parental involvement and repeated practice (Eveleigh 2010; Reaven and Hepburn 2006).

The importance of assessing intervention effectiveness in real life, i.e., social validity, is widely acknowledged but seldom practiced in behavioral intervention research for individuals with disabilities (Brosnan and Healy 2011; Finn and Sladeczek 2001; Kroeger and Sorensen-Burnworth 2009). Given the relative complexity of the reviewed interventions and the considerable therapist hours invested, it is reasonable to check the interventions’ social validity in order to rationalize their possibly higher cost. Not all reviewed studies reported on social validity and the measures used were rating scales and questionnaires completed by parents, which are potentially subjective.

Based on this review, no evidence is found regarding the efficacy of CBA for lower-functioning children with ASD or for interventions carried out in school settings. Evidence is extremely limited for its efficacy with difficulties other than anxiety. There is also the need to measure the social validity of these interventions with more comprehensive and objective methods.

Study Quality

The superiority of randomized controlled trials depends on the group equivalence achieved through the random allocation of participants into treatment or control conditions, adjustment for pretest and posttest covariance difference being made, raters being blind to the group allocation, and ensuring procedural fidelity. Only half of all the reviewed studies met half or more than half of all the research design quality criteria satisfactorily. The average study quality scored just over half of the possible maximum, and study quality appeared to be a possible variance moderator of the ESs in that lower quality studies produced higher ESs.

Recommendations for Further Research

Although it is argued that CBA might be particularly suitable to children with ASD with higher cognitive abilities (Klinger and Williams 2009; Ozonoff 1999; Whyte 2009), the current narrow focus restrains the development of a thorough understanding of the application of CBA to children with ASD and with lower cognitive abilities (Rotheram-Fuller and MacMullen 2011). One of the very few research studies intervening with participants with ASD and with lower cognitive abilities incorporated CBA as a major component of its treatment protocol, and positive effects were reported (Pardini et al. 2012). Positive results were also reported in studies on CBA interventions for anger management for adults with intellectual disabilities (Taylor and Novaco 2005). As 50 to 70 % of individuals with ASD have intellectual disabilities (Matson and Shoemaker 2009), there may be potential benefits in extending CBA interventions to children with ASD and intellectual disabilities. To deepen the understanding on the feasibility of CBA for children with ASD, it may be important to quantify participant verbal IQ as well as level of autistic symptomology in the future studies.

To expand the application of CBA for children with ASD, the potential of implementing CBA in school settings by classroom teachers should be investigated. The possible efficacy of CBA carried out by teachers in school settings and the potential of facilitating the application of learnt skills in daily natural contexts were demonstrated in some studies (Bauminger 2002, 2007a, b; Bolton et al. 2012). To extend the application of learnt skills to the children’s daily lives, given the possible moderating effects of parent involvement found in this review, future research should include active parent involvement in the child’s home environment. Given the current success of CBA interventions with anxiety, exploring the feasibility of CBA for impulsive behaviors, academic tasks, problem solving ability, role taking, and self-control would be reasonable directions to take. CBA has been used with success to intervene on these targets in typically developing children (e.g., Kendall and Braswell 1985; Little and Kendall 1979; Meichenbaum and Asarnow 1979; Meichenbaum and Goodman 1971).

Due to the high treatment cost and high service needs in the population with ASD, an effective and acceptable intervention should include only the effective components or necessary features (Foster et al. 2007; Jacobson and Mulick 2000). Future research should include more comparison studies to clarify the relative effectiveness of individual components and features. Parental involvement and the teaching of problem solving and self-instructions are two such components to be considered. Some indicative support for parental involvement is found in this review, and the teaching of problem solving and self-instructions are suggested for programming generalization and maintenance in the literature (Kendall and Finch 1979; Little and Kendall 1979; Meichenbaum and Asarnow 1979).

One problem in interpreting the intervention results is the heterogeneity of CBA interventions. A question to ask is whether RCT is the best research method to investigate the relative efficacy of elements in complex multiple-component interventions. A reasonable alternative research method may be small-n designs; which are recommended for investigating multiple-component interventions, comparing alternative interventions in special education, and for children with ASD (Horner et al. 2005; Odom et al. 2005; Odom et al. 2010; Sheffield and Waller 2010).

In order to objectively measure the intervention outcomes and mitigate the issues with standardized measures, observations in natural settings of the behaviors concerned as well as the measures of actual improvement in participant quality of life should be more frequently used in future studies. Observation of actual behavior changes and the actual improvement in participant quality of life could also serve to measure social validity, which is currently measured with parent questionnaires only in the reviewed studies.

Conclusion

The present review suggested that CBA to manage anxiety, delivered in clinical settings, could be highly effective for high-functioning children with ASD. This conclusion is qualified by the heterogeneity of the reviewed interventions, the heavy reliance on standard rating scales completed by participants and parents, and the lack of satisfactory documentation of randomization of participants in some studies. Future research should investigate the feasibility of CBA in school settings, the applicability for lower-functioning children with ASD, and also address difficulties other than anxiety. Small n designs are recommended for detailed comparisons of the various intervention components, in particular for determining which common cognitive components (i.e., cognitive restructuring, self-instruction and problem solving) are appropriate and necessary for children with ASD. The observation of targeted behaviors in natural settings by observers blind to intervention conditions should be used to measure the intervention outcomes.

References

*Indicates study included in the review

Anderson, S., & Morris, J. (2006). Cognitive behaviour therapy for people with Asperger syndrome. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 34, 293–303. doi:10.1017/S1352465805002651.

Attwood, T. (2003). Cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT). In L. H. Willey (Ed.), Asperger syndrome in adolescence: living with the ups and downs and things in between (pp. 38–68). London: Jessica Kingsley.

Attwood, T. (2004). Cognitive behaviour therapy for children and adults with Asperger’s syndrome. Behaviour Change, 21, 147–161. doi:10.1375/bech.21.3.147.55995.

Baker, J. E., & Myles, B. S. (2003). Social skills training for children and adolescents with Asperger syndrome and social-communication problems. US: Autism Asperger.

Barnhill, G. P. (2007). Outcomes in adults with Asperger syndrome. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 22, 116–126. doi:10.1177/10883576070220020301.

Baron-Cohen, S., Leslie, A. M., & Frith, U. (1985). Does the autistic child have a “theory of mind” ? Cognition, 21, 37–46. doi:10.1016/0010-0277(85)90022-8.

Barsky, S. J. (2001). A comprehensive treatment program for elementary students with Asperger’s syndrome. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database. (UMI No. 3040758)

Bauminger, N. (2002). The facilitation of social-emotional understanding and social interaction in high-functioning children with autism: intervention outcomes. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 32, 283–298. doi:10.1023/A:1016378718278.

Bauminger, N. (2007a). Brief report: group social-multimodal intervention for HFASD. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37, 1605–1615. doi:10.1007/s10803-006-0246-3.

Bauminger, N. (2007b). Brief report: individual social-multi-modal intervention for HFASD. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37, 1593–1604. doi:10.1007/s10803-006-0245-4.

Beaumont, R., & Sofronoff, K. (2008). A multi-component social skills intervention for children with Asperger syndrome: the Junior Detective Training Program. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49, 743–753. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01920.x.

Beck, R., & Fernandez, E. (1998). Cognitive-behavioral therapy in the treatment of anger: a meta-analysis. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 22, 63–74. doi:10.1023/A:1018763902991.

Bolton, J. B., McPoyle-Callahan, J. E., & Christner, R. W. (2012). Autism: school-based cognitive-behavioral interventions. In R. B. Mennuti, R. W. Christner, & A. Freeman (Eds.), Cognitive-behavioral interventions in educational settings: a handbook for practice (2nd ed., pp. 469–501). New York: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

Borenstein, M., Hedges, L., Higgins, J., & Rothstein, H. R. (2005). Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (Version 2) [Computer software]. Englewood: Biostat.

Borenstein, M., Hedges, L., Higgins, J., & Rothstein, H. (2009). Introduction to meta-analysis. West Sussex: Wiley.

Braswell, L., & Kendall, P. C. (1988). Cognitive-behavioral methods with children. In K. S. Dobson (Ed.), Handbook of cognitive-behavioral therapies (pp. 167–213). New York: Guilford Press.

Brosnan, J., & Healy, O. (2011). A review of behavioral interventions for the treatment of aggression in individuals with developmental disabilities. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 32, 437–446. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2010.12.023.

Butler, A. C., Chapman, J. E., Forman, E. M., & Beck, A. T. (2006). The empirical status of cognitive-behavioral therapy: a review of meta-analyses. Clinical Psychology Review, 26, 17–31. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2005.07.003.

Cappadocia, M., & Weiss, J. A. (2011). Review of social skills training groups for youth with Asperger syndrome and high functioning autism. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 5, 70–78. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2010.04.001.

Cardaciotto, L., & Herbert, J. D. (2004). Cognitive behavior therapy for social anxiety disorder in the context of Asperger’s syndrome: a single-subject report. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 11, 75–81. doi:10.1016/s1077-7229(04)80009-9.

* Chalfant, A. M., Rapee, R., & Carroll, L. (2007). Treating anxiety disorders in children with high functioning autism spectrum disorders: a controlled trial. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37, 1842–1857. doi:10.1007/s10803-006-0318-4.

Cimera, R. E., & Cowan, R. J. (2009). The costs of services and employment outcomes achieved by adults with autism in the US. Autism, 13, 285–302. doi:10.1177/1362361309103791.

Crawley, S. A., Podell, J. L., Beidas, R. S., Braswell, L., & Kendall, P. C. (2010). Cognitive-behavioral therapy with youth. In K. S. Dobson (Ed.), Handbook of cognitive behavioral therapies (3rd ed., pp. 375–411). New York: The Guilford Press.

Dansey, D., & Peshawaria, R. (2009). Adapting a desensitisation programme to address the dog phobia of an adult on the autism spectrum with a learning disability. Good Autism Practice, 10, 9–14.

Dobson, K. S., & Dozois, D. J. (2010). Historical and philosophical bases of the cognitive-behavioral therapies. In K. S. Dobson (Ed.), Handbook of cognitive behavioral therapies (3rd ed., pp. 3–38). New York: The Guilford Press.

Donoghue, K., Stallard, P., & Kucia, J. (2011). The clinical practice of cognitive behavioural therapy for children and young people with a diagnosis of Asperger’s syndrome. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 16, 89–102. doi:10.1177/1359104509355019.

* Drahota, A. M. (2008). Intervening with independent daily living skills for high-functioning children with autism and concurrent anxiety disorders. Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences, 69(7-A), 2601.

* Drahota, A., Wood, J., Sze, K., & Dyke, M. (2011). Effects of cognitive behavioral therapy on daily living skills in children with high-functioning autism and concurrent anxiety disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 41, 257–265. doi:10.1007/s10803-010-1037-4.

Duffy, C., & Healy, O. (2011). Spontaneous communication in autism spectrum disorder: a review of topographies and interventions. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 5, 977–983. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2010.12.005.

Edwards, N., Peterson, W. E., & Davies, B. L. (2006). Evaluation of a multiple component intervention to support the implementation of a ‘Therapeutic Relationships’ best practice guideline on nurses’ communication skills. Patient Education and Counseling, 63(1–2), 3–11. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2006.07.008.

Epp, K. M. (2008). Outcome-based evaluation of a social skills program using art therapy and group therapy for children on the autism spectrum. Children and Schools, 30, 27–36. doi:10.1093/cs/30.1.27.

Eveleigh, E. L. (2010). Examining instructional efficiency among flashcard drill and practice methods with a sample of first grade students. Doctoral Dissertation, The Ohio State University, Ohio, United States

Finn, C. A., & Sladeczek, I. E. (2001). Assessing the social validity of behavioral interventions: a review of treatment acceptability measures. School Psychology Quarterly, 16, 176. doi:10.1521/scpq.16.2.176.18703.

Fitzgerald, G. E., & Werner, J. G. (1996). The use of the computer to support cognitive-behavioral interventions for students with behavioral disorders. Journal of Computing in Childhood Education, 7, 127–148.

Foster, E. M., Olchowski, A. E., & Webster-Stratton, C. H. (2007). Is stacking intervention components cost-effective? An analysis of the Incredible Years Program. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 46, 1414–1424. doi:10.1097/chi.0b013e3181514c8a.

Garcia-Winner, M. (2002). Thinking about you, thinking about me. San Jose: Michelle Garcia-Winner.

Garcia-Winner, M. (2007). Thinking about you, thinking about me (2 ed.). San Jose: Think Social Publishing.

Gersten, R., Fuchs, L. S., Compton, D., Coyne, M., Greenwood, C., & Innocenti, M. S. (2005). Quality indicators for group experimental and quasi-experimental research in special education. Exceptional Children, 71, 149–164.

Gooding, L. F. (2010). The effect of a music therapy-based social skills training program on social competence in children and adolescents with social skills deficits. (Doctoral Dissertation). Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses (UMI No. 3415221)

Graham, P. (2005). Jack Tizard lecture: cognitive behaviour therapies for children: passing fashion or here to stay? Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 10, 57–62. doi:10.1111/j.1475-3588.2005.00119.x.

Gratton, S. (2010). Psychological interventions. In R. Raghavan, S. H. Bernard, & J. McCarthy (Eds.), Mental health needs of children and young people with learning disabilities (pp. 97–115). Brighton: Pavilion.

Greig, A., & MacKay, T. (2005). Asperger’s syndrome and cognitive behaviour therapy: new applications for educational psychologists. Educational and Child Psychology, 22, 4–15.

Groden, J., & LeVasseur, P. (1995). Cognitive picture rehearsal: a system to teach self-control. In K. A. Quill (Ed.), Teaching children with autism: strategies to enhance communication and socialization (pp. 287–306). New York: Delmar Publishers.

Grosso, C. A. (2012). Children with developmental disabilities. In J. A. Cohen, A. P. Mannarino, & E. Deblinger (Eds.), Trauma-focused CBT for children and adolescents: treatment applications (pp. 149–174). New York: Guilford Press.

Happé, F., & Frith, U. (2006). The weak coherence account: detail-focused cognitive style in autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 36(1), 5–25. doi:10.1007/s10803-005-0039-0.

Hare, D. J. (1997). The use of cognitive-behavioral therapy with people with Asperger syndrome: a case study. Autism, 1, 215–225. doi:10.1177/1362361397012007.

Hill, E. L. (2004). Executive dysfunction in autism. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 8, 26–32. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2003.11.003.

Horner, R. H., Carr, E. G., Halle, J., Mcgee, G., Odom, S., & Wolery, M. (2005). The use of single-subject research to identify evidence-based practice in special education. Exceptional Children, 71, 165–179.

Howlin, P., Baron-Cohen, S., & Hadwin, J. (1999). Teaching children with autism to mind-read: a practical guide for teachers and parents. Chichester: Wiley.

Hurtig, T., Kuusikko, S., Mattila, M.-L., Haapsamo, H., Ebeling, H., Jussila, K., & Moilanen, I. (2009). Multi-informant reports of psychiatric symptoms among high-functioning adolescents with Asperger syndrome or autism. Autism, 13, 583–598. doi:10.1177/1362361309335719.

Jacobson, J. W., & Mulick, J. A. (2000). System and cost research issues in treatments for people with autistic disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 30, 585. doi:10.1023/A:1005691411255.

Johnson, S. A., Filliter, J. H., & Murphy, R. R. (2009). Discrepancies between self- and parent-perceptions of autistic traits and empathy in high-functioning children and adolescents on the autism spectrum. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 39, 1706–1714. doi:10.1007/s10803-009-0809-1.

Kasari, C., & Lawton, K. (2010). New directions in behavioral treatment of autism spectrum disorders. Current Opinion in Neurology, 23, 137–143. doi:10.1097/WCO.0b013e32833775cd.

Kellner, M. H., & Tutin, J. (1995). A school-based anger management program for developmentally and emotionally disabled high school students. Adolescence, 30, 813–825.

Kendall, P. C., & Braswell, L. (1985). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for impulsive children. New York: Guilford Press.

Kendall, P. C., & Finch, A. J. (1979). Developing nonimpulsive behavior in children: cognitive-behavioral strategies for self-control. In P. C. Kendall & S. D. Hollon (Eds.), Cognitive-behavioral interventions: theory, research, and procedures (pp. 37–80). New York: Academic Press.

Kendall, P. C., & Hedtke, K. A. (2006a). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxious children: therapist manual (3rd ed.). Ardmore: Workbook Publishing.

Kendall, P. C., & Hedtke, K. A. (2006b). The coping cat workbook (2nd ed.). Ardomre: Workbook Publishing.

Kendall, P. C., Chu, B., Gifford, A., Hayes, C., & Nauta, M. (1998). Breathing life into a manual: flexibility and creativity with manual-based treatments. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 5, 177–198. doi:10.1016/s1077-7229(98)80004-7.

Kincade, S. R. (2009). CBT and autism spectrum disorders: a comprehensive literature review. (Master’s thesis), University of Lethbridge, Alberta, Canada.

Klinger, L. G., & Williams, A. (2009). Cognitive-behavioral interventions for students with autism spectrum disorders. In M. J. Mayer, J. E. Lochman, & R. Van Acker (Eds.), Cognitive-behavioral interventions for emotional and behavioral disorders: school-based practice (pp. 328–362). New York: Guilford Press.

Knapp, M., Romeo, R., & Beecham, J. (2009). Economic cost of autism in the UK. Autism: the International Journal of Research and Practice, 13, 317–336. doi:10.1177/1362361309104246.

* Koning, C. (2010). Efficacy of CBT-based social skills intervention for school-aged boys with autism spectrum disorders. (Doctoral Dissertation), University of Alberta, Canada.

Kroeger, K. A., & Sorensen-Burnworth, R. (2009). Toilet training individuals with autism and other developmental disabilities: a critical review. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 3, 607–618. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2009.01.005.

Kruzynski, A. K. (1998). Play in toddlers with pervasive developmental disorder and autism: alternative assessment procedures and impact of treatment. (Master’s Thesis), McGill University, Quebec, Canada.

Lang, R., Regester, A., Lauderdale, S., Ashbaugh, K., & Haring, A. (2010). Treatment of anxiety in autism spectrum disorders using cognitive behaviour therapy: a systematic review. Developmental Neurorehabilitation, 13, 53–63. doi:10.3109/17518420903236288.

Lerner, M. D. (2013). Knowledge or performance: why youth with autism experience social problems? (Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation), University of Virginia, Virginia, United States.

Lim, S. M., Kattapuram, A., & Lian, W. B. (2007). Evaluation of a pilot clinic-based social skills group. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 70, 35–39.

Little, V., & Kendall, P. C. (1979). Cognitive-behavioral interventions with delinquents: problem solving, role-taking, and self-control. In P. C. Kendall & S. D. Hollon (Eds.), Cognitive-behavioral interventions: theory, research, and procedures (pp. 81–115). New York: Academic Press.

Luckett, T., Bundy, A., & Roberts, J. (2007). Do behavioural approaches teach children with autism to play or are they pretending? Autism: the International Journal of Research and Practice, 11, 365–388. doi:10.1177/1362361307078135.

Lyneham, H., Abbott, M., Wignall, A., & Rapee, R. (2003). The cool kids family program—therapist manual. Sydney, Australia: Macquarie University.

Matson, J. L., & Shoemaker, M. (2009). Intellectual disability and its relationship to autism spectrum disorders. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 30, 1107–1114. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2009.06.003.

Mazefsky, C. A., Kao, J., & Oswald, D. P. (2011). Preliminary evidence suggesting caution in the use of psychiatric self-report measures with adolescents with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 5, 164–174. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2010.03.006.

McGee, G. G., Krantz, P. J., Mason, D., & McClannahan, L. E. (1983). A modified incidental-teaching procedure for autistic youth: acquisition and generalization of receptive object labels. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 16, 329. doi:10.1901/jaba.1983.16-329.

* McNally Keehn, R. (2010). Effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy for children with high functioning autism and anxiety. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses. (UMI No. 3428759)

Meichenbaum, D. H., & Asarnow, I. (1979). Cognitive-behavior modification and metacognitive development: implications for the classroom. In P. C. Kendall & S. D. Hollon (Eds.), Cognitive-behavioral interventions: theory, research, and procedures (pp. 11–35). New York: Academic Press.

Meichenbaum, D. H., & Goodman, J. (1971). Training impulsive children to talk to themselves: a means of developing self-control. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 77, 115–126. doi:10.1037/h0030773.

Moree, B. N., & Davis, T. E., III. (2010). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety in children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorders: modification trends. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 4, 346–354. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2009.10.015.

National Research Council. (2001). Educating children with autism. C. Lord & J. P. McGee (Eds.). Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Odom, S. L., Brantlinger, E., Gersten, R., Horner, R. H., Thompson, B., & Harris, K. R. (2005). Research in special education: scientific methods and evidence-based practices. Exceptional Children, 71, 137–148.

Odom, S. L., Collet-Klingenberg, L., Rogers, S. J., & Hatton, D. D. (2010). Evidence-based practices in interventions for children and youth with autism spectrum disorders. Preventing School Failure: Alternative Education for Children and Youth, 54, 275–282. doi:10.1080/10459881003785506.

Ooi, Y. P., Lam, C. M., Sung, M., Tan, W. T. S., Goh, T. J., Fung, D. S. S., & Chua, A. (2008). Effects of cognitive-behavioural therapy on anxiety for children with high-functioning autistic spectrum disorders. Singapore Medical Journal, 49, 215–220.

Ozonoff, S. J. (1999). Brief report: specific executive function profiles in three neurodevelopmental disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 29, 171–177. doi:10.1023/A:1023052913110.

Pardini, M., Elia, M., Garaci, F., Guida, S., Coniglione, F., Krueger, F., & Emberti Gialloreti, L. (2012). Long-term cognitive and behavioral therapies, combined with augmentative communication, are related to uncinate fasciculus integrity in autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42, 585–592. doi:10.1007/s10803-011-1281-2.

Perry, T. D. (2008). A pilot study of social cognition training for adults with high-functioning autism. (Master’s Thesis). Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses (UMI No. 1452917)

Puleo, C., & Kendall, P. (2011). Anxiety disorders in typically developing youth: autism spectrum symptoms as a predictor of cognitive-behavioral treatment. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 41, 275–286. doi:10.1007/s10803-010-1047-2.

Reaven, J., & Hepburn, S. (2006). The parent’s role in the treatment of anxiety symptoms in children with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders. Mental Health Aspects of Developmental Disabilities, 9, 73–80.

Reaven, J., Blakeley-Smith, A., Nichols, S., Dasari, M., Flanigan, E., & Hepburn, S. (2009). Cognitive-behavioral group treatment for anxiety symptoms in children with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders: a pilot study. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 24, 27–37. doi:10.1177/1088357608327666.

* Reaven, J., Blakeley-Smith, A., Culhane-Shelburne, K., & Hepburn, S. (2012). Group cognitive behavior therapy for children with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders and anxiety: a randomized trial. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 53, 410–419. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02486.x.

Rincover, A., & Koegel, R. L. (1975). Setting generality and stimulus control in autistic children. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 8, 235–246. doi:10.1901/jaba.1975.8-235.

Rotheram-Fuller, E., & MacMullen, L. (2011). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for children with autism spectrum disorders. Psychology in the Schools, 48, 263–271. doi:10.1002/pits.20552.

* Scarpa, A., & Reyes, N. M. (2011). Improving emotion regulation with CBT in young children with high functioning autism spectrum disorders: a pilot study. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 39, 495–500. doi:10.1017/S1352465811000063.

Scott, M. J. (2009). Simply effective cognitive behaviour therapy: a practitioner’s guide London: Routledge

Sheffield, K., & Waller, R. J. (2010). A review of single-case studies utilizing self-monitoring interventions to reduce problem classroom behaviors. Beyond Behavior, 19(2), 7–13.

Snell, J. A. (2012). Group therapy for children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses database. (UMI No. 3481088)

* Sofronoff, K., Attwood, T., & Hinton, S. (2005). A randomised controlled trial of a CBT intervention for anxiety in children with Asperger syndrome. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 46, 1152–1160. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.00411.x.

* Sofronoff, K., Attwood, T., Hinton, S., & Levin, I. (2007). A randomized controlled trial of a cognitive behavioural intervention for anger management in children diagnosed with Asperger syndrome. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37, 1203–1214. doi:10.1007/s10803-006-0262-3.

* Sung, M., Ooi, Y. P., Goh, T. J., Pathy, P., Fung, D. S., Ang, R. P., & Lam, C. M. (2011). Effects of cognitive-behavioral therapy on anxiety in children with autism spectrum disorders: a randomized controlled trial. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 42, 634–649. doi:10.1007/s10578-011-0238-1.

Taylor, J. L., & Novaco, R. W. (2005). Anger treatment for people with developmental disabilities. In Anger treatment for people with developmental disabilities: a theory, evidence and manual based approach (pp. 43–66). Chichester: Wiley.

Vickers, B. (2002). Cognitive behaviour therapy for adolescents with psychological disorders: a group treatment programme. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 7, 249–262. doi:10.1177/1359104502007002011.

Volker, M. A., & Lopata, C. (2008). Autism: a review of biological bases, assessment, and intervention. School Psychology Quarterly, 23, 258–270. doi:10.1037/1045-3830.23.2.258.

Wang, P., & Spillane, A. (2009). Evidence-based social skills interventions for children with autism: a meta-analysis. Education and Training in Developmental Disabilities, 44, 318–342.

Weiss, J. A., & Lunsky, Y. (2010). Group cognitive behaviour therapy for adults with Asperger syndrome and anxiety or mood disorder: a case series. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 17, 438–446. doi:10.1002/cpp.694.

White, A. H. (2004). Cognitive behavioural therapy in children with autistic spectrum disorders. In Bazian Ltd (Ed.), STEER: Succinct and Timely Evaluated Evidence Reviews, 4 (5). http://www.signpoststeer.org/. Accessed 23 Nov 2010.

White, S. W., Oswald, D., Ollendick, T., & Scahill, L. (2009). Anxiety in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Clinical Psychology Review, 29, 216–229. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2009.01.003.

Whyte, T. (2009). Asperger syndrome and anxiety: what does research tell us about the effectiveness of cognitive behaviour therapy? Good Autism Practice, 10(2), 27–34.

* Wood, J., Drahota, A., Sze, K., Har, K., Chiu, A., & Langer, D. A. (2009a). Cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety in children with autism spectrum disorders: a randomized, controlled trial. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 50, 224–234. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01948.x.

* Wood, J., Drahota, A., Sze, K., Van Dyke, M., Decker, K., Fujii, C., & Spiker, M. (2009b). Brief report: effects of cognitive behavioral therapy on parent-reported autism symptoms in school-age children with high functioning autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 39, 1608–1612. doi:10.1007/s10803-009-0791-7.

Wood, J. J., & McLeod, B. D. (2008). Child anxiety disorders: A family treatment manual for practitioners. New York: Norton.

Zelazo, P. (1997). Infant-toddler information processing treatment of children with pervasive developmental disorder and autism: part II. Infants & Young Children, 10(2), 1–13. doi:10.1097/00001163-199710000-00004.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ho, B.P.V., Stephenson, J. & Carter, M. Cognitive-Behavioral Approach for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders: a Meta-Analysis. Rev J Autism Dev Disord 1, 18–33 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-013-0002-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-013-0002-5