Abstract

Developmental coordination disorder (DCD) is a highly prevalent, chronic disability, which significantly impacts a child’s ability to perform everyday motor-based tasks. Although first and foremost a disorder involving coordinated movement, DCD also is associated with a range of psychological problems. In this article, we review evidence documenting the social and emotional problems experienced by children with DCD. We then examine potential causal explanations, including recent evidence suggesting that DCD is a primary stressor that “triggers” exposure to a complex set of secondary stressors, which collectively lead to psychological distress. Within this context, we consider how various personal and environmental factors might mediate or interrupt the trajectory of poor psychological outcomes in DCD. We identify limitations in the current evidence and suggest directions for future research, including the proposition that evidence-based interventions be leveraged as a means of establishing causal pathways while simultaneously providing much needed support to children with DCD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Developmental coordination disorder (DCD) is a common and chronic health condition, which impacts a child’s ability to perform everyday tasks at home, at school, and at play [1–4]. While there is no question that DCD is a disorder of coordinated movement, it has been associated with a wide range of psychological problems. Whether these social and emotional problems are comorbid (i.e., co-occur) with DCD, or whether they are secondary consequences of DCD, is an issue of considerable debate [5]. In this article, we review the now vast body of literature that has established the specific types of psychological problems associated with DCD. Emerging evidence supports the position that DCD is the primary disorder and that the psychological issues arise from a complex set of factors, including personal factors (e.g., lower self-esteem and poorer social skills), social factors (e.g., fewer friendships and greater social isolation), and environmental factors (e.g., inadequate social and academic supports) [6••, 7–9]. Causal explanations are explored, including some that have received less attention to date. Implications are discussed for evidence-based management of these children and also for future research.

What Is Developmental Coordination Disorder?

DCD is a motor-based learning disorder and has been recognized as a diagnosable health condition for the last 25 years [1, 10, 11]. The most recent Diagnostic and Statistical Manual [1] (DSM-V) has incorporated far more current evidence into its description of the characteristics of DCD than the previous edition. DCD is described as a motor skill disorder, which is present when “the acquisition and execution of coordinated motor skills is substantially below that expected given the individuals’ chronological age and opportunity for skill learning and use” [1; F82]. The European Academy of Childhood Disability recently summarized existing evidence and recognized DCD as a unique and separate neurodevelopmental disorder, even though it often co-exists with other neurobehavioral disorders such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), specific language impairment, and dyslexia [12•]. With an estimated prevalence of 1.8–6 % [13], it is likely that there is a child with DCD in every classroom in the world; yet, few educational or healthcare systems acknowledge or understand it [2, 12•, 14, 15]. The motor skill deficits of these children impact on everyday self-care (e.g., doing up snaps or zippers, brushing teeth, climbing stairs), academic performance (e.g., printing, using scissors, keyboarding, physical education class), and leisure activities (e.g., ball sports, bicycle riding). The underlying motor deficits vary across children and are still not fully understood; however, they have significant impact on the child’s ability to learn and perform everyday tasks that require coordination [16•]. Despite the fact that motor deficits impact on the skills that children typically learn as preschoolers, problems can be subtle and often go unnoticed until they begin to affect academic performance [17–19].

Compelling evidence shows that the motor problems of children with DCD are life-long [20–23]. Indeed, Criterion B of DSM-V formally acknowledges the ongoing impact of motor skill difficulties on the pre-vocational and vocational activities that are typical of adolescence and adulthood [1]. The potential temporal causality of DCD also has been suggested through the addition of Criterion C, which states that symptom onset is in the early developmental period. Finally, the fact that DCD is a primary motor deficit is reflected in Criterion D, which indicates that the motor skill delay is not better explained by other intellectual or neurological causes [1].

What Are the Implications of Having DCD?

The consequences of DCD on children’s physical health have been well documented in the past decade in both clinical and population-based samples. These include reduced physical fitness [24, 25] and participation in physical activity [26–28], and an increased likelihood that children with DCD will become overweight/obese [29–32]. The psychological, or mental health, issues associated with DCD are the focus of the remainder of this article.

In 2001, Skinner and Piek published a pivotal article, which drew attention to the psychosocial implications of having poor motor coordination as a child. At a time when many studies were focused only on the motor impairments of children with DCD, Skinner and Piek demonstrated that children with DCD had lower global self-worth than their typically developing peers, experienced more anxiety, and perceived that they had less social support; moreover, these psychological issues worsened in older children [33]. More than a decade later, studies using a wide variety of sampling procedures and methods have affirmed that children with DCD are at increased risk for numerous social, emotional, and mental health difficulties, including peer problems [34]; decreased participation in social activities [35]; social isolation and loneliness [36]; increased risk for peer victimization [37]; reduced self-concept and/or self-esteem [38–40]; and increased symptoms of anxiety and depression [41–46]. Although the evidence consistently shows that these psychological issues co-exist with DCD, causality has yet to be established.

Recently, Cairney and colleagues [5, 6••] described a conceptual model for testing causal pathways from DCD to the emergence of psychological problems. Termed the “environmental stress hypothesis,” this model positions the core motor impairment of DCD as a primary stressor, which almost inevitably leads a child to be exposed to multiple secondary stressors (e.g., frustration with and withdrawal from physical activities; reduced opportunities for social interaction with peers; increased risk for obesity; poor academic performance; and vulnerability to teasing, bullying, and social exclusion). Over time, exposure to these secondary stressors may lead a child to make negative self-appraisals and develop low self-esteem. In turn, it is the low self-esteem and feelings of incompetence that ultimately give rise to internalizing disorders such as depression and anxiety. Although this model has only recently been proposed, preliminary evidence is very supportive. For example, Lingam and colleagues (2012) reported findings from a 3-year longitudinal study in which children identified with probable DCD at age 7 were re-assessed for mental health difficulties at age 10. Similar to prior research, their findings showed that children at risk for DCD were significantly more likely to develop mental health problems relative to their peers [7]. Even more interesting, Lingam et al. found that several factors mediated the connection between DCD and subsequent mental health problems. Specifically, those children with probable DCD who had higher verbal intelligence, higher self-esteem, stronger academic performance, good social communication skills, and an absence of bullying were less likely to develop mental health difficulties over time [7].

Consistent with this notion of “intermediary” factors, Wilson, Piek, and Kane (2013) [9] recently reported that social skills fully mediated the relationship between motor coordination and emotional problems in a large sample of 4- to 6-year-old children. The authors suggested that children with poor motor coordination may not learn important peer-related social skills, because they tend to withdraw from many of the situations in which these skills are learned (i.e., active physical play). In turn, less effective social skills may place a child at risk for emotional problems—either directly or indirectly—by constraining children’s social participation. However, given that their data were cross-sectional rather than longitudinal, conclusions about causality are not possible. This also is true of recent findings reported by Rigoli, Piek, and Kane (2012) [8]. In their study, adolescents from a normative, non-clinical sample were found to have poorer emotional well-being if they had poorer motor coordination abilities; moreover, this relationship was fully mediated by the impact that motor coordination exerted on self-perceptions of competence. In other words, adolescents who were less coordinated viewed themselves more negatively, and that, in turn, was related to poorer emotional well-being. Once again, owing to the cross-sectional nature of the data, causality cannot be verified. In addition, for both of these studies by Piek and colleagues, it is not known if the same relationships would hold had the study samples included children across the full range of motor coordination ability (i.e., children with typical motor coordination ability as well as more children who would have met formal diagnostic criteria for DCD).

What Are the Limitations of the Research to Date?

To address the limitations of cross-sectional studies, prospective longitudinal research is needed, starting when children are young, before the psychological problems have emerged. Moreover, these studies require a population-based approach that captures the full range of children with DCD – not just those children with the most severe problems who have been referred for clinical services or those in a normative range of ability. Referred children are not likely to be representative of the majority of children with DCD, whose problems go undetected by the health and education systems [41, 47]. In addition, with the exception of Lingam et al. (2012) [7], only a single mediating variable has been considered at a time, which limits the amount of variance in psychological outcomes that can be explained. Therefore, large-scale studies are needed that can examine the effects of multiple mediating factors.

Also largely unexplored is the role that comorbidity of other disorders might play as either a primary or secondary stressor in a larger causal model. Evidence strongly suggests that those children with more than one developmental disorder are at the greatest risk for poor psychological outcomes. For example, Missiuna and colleagues [41] used a comprehensive, population-based screening approach to identify children aged 9–14 years who had motor and/or attention impairments. Self-report and parent-report measures showed that children who met diagnostic criteria for DCD had significantly more symptoms of depression and anxiety than typically developing children; however, children who had both DCD and ADHD were found to be at the greatest risk [41]. A number of other research studies also have found that comorbidity increases the risk for psychological problems [48, 49]. However, to date, we do not know precisely how comorbidities contribute to the development of psychological difficulties in children with DCD. This is an area that requires further exploration.

What Factors Have Yet to Be Considered?

In addition to exploring what factors may give rise to psychological problems in children with DCD, Cairney et al. [6••] also explored those factors that might “interrupt” the pathway from secondary stressors to psychological problems. For example, factors internal to the child (e.g., temperament, coping skills, perceived competence) and external to the child (e.g., social support; timely access to appropriate health services; accommodations) might influence the secondary stressors associated with DCD in a protective fashion. The importance of identifying such factors cannot be overstated, as some of these variables are modifiable and could be targeted through intervention. A focus on interventions that may be preventative is particularly important in light of the mounting evidence that DCD is a chronic condition that cannot be “fixed” and will persist into adulthood [20–22, 50].

The trajectory through which DCD might lead to mental health issues became evident when Missiuna and colleagues conducted an in-depth qualitative study with 13 parents of children with DCD to explore what their families first noticed [51]. The stress experienced by families was considerable as they took their child from one health professional to another, seeking a diagnosis and repeatedly emphasizing during each visit that “something’s wrong with my child” [51, 52]. Moreover, consider the potential impact of this process on the child, who is already frustrated trying to keep up with their peers. Now, he or she must listen repeatedly to descriptions of their difficulties while possibly also enduring any combination of genetic testing, MRIs, muscle biopsies, motor impairment testing, and psychological assessment – all without an answer [15]. Sugden and colleagues postulated that the first “clinic door” through which a child passes shines a spotlight on particular clusters of symptoms, hence influencing the assessment process and the diagnosis that may be given [53]. As an illustrative example, handwriting problems are the primary reason for referral of children with DCD to occupational therapy [54]; however, handwriting difficulty is generally only the “tip of the iceberg” [55]. Associated psychosocial issues may never be identified or addressed. Conversely, child psychiatrists [56] and physicians [14, 57] may recognize symptoms of ADHD, anxiety, or depression, but owing to a lack of awareness about DCD, the underlying motor disorder may go undetected. Parental efforts to seek an explanation—without finding one [19]—may be one factor that impacts on a child’s self-esteem and later mental health problems.

Assuming that the child with DCD and their family eventually reach the point of having the child’s motor coordination difficulties identified, the impact of subsequent services on the child and family is rarely considered. For example, the majority of intervention approaches described to date focus at the level of changing the child’s underlying motor impairment and are delivered in a 1:1 context, which often does not meet the needs of the child or family [58–60]. Although there may be circumstances in which this may be an appropriate approach, it is worth considering how singling a child out, assessing their motor deficits, and providing remediation might impact on a child’s emotional well-being. Instead, more inclusive approaches that extend beyond the individual child to encompass education of the family, the school, and the community may lead to better understanding of the child’s motor challenges; in turn, a more supportive environment may be protective and prevent the onset of further problems. A qualitative study of nine resilient adults with DCD indicated that their positive recollections were not of therapeutic situations but of being supported by families and others [23]. They expressed that accommodations, or modifications, made at home (e.g., a reminder board to guide morning routines; an electric toothbrush), at school (e.g., using a laptop or peer note-taker), and in the community (e.g., keeping score during a sports match rather than playing competitively; helping peers with homework in exchange for help with a challenging physical task), as well as intra-personal strengths (i.e., finding something they were good at; using humor to keep things in perspective), had increased their ability to participate successfully in different settings and to make a successful transition to adulthood.

Where Do We Go From Here?

We previously noted that longitudinal studies are necessary to establish temporal causation. However, it is becoming increasingly difficult to justify prospective, longitudinal studies that monitor the onset and progression of anxiety and depression without attempting to change the outcome. If, as suggested by Cairney et al. [5, 6••], there are “intermediary” factors that can mediate or change the mental health trajectory of children with DCD, then another way of establishing causality would be to trial interventions that target potential mediating variables and then monitor psychological outcomes. “Partnering for Change” (P4C) is an evidence-based intervention that is attempting to do this [61]. The intervention was developed on the basis of theory and research about the needs of children with DCD in conjunction with research about strategies and accommodations that are useful to enhance children’s participation [62]. Working from a chronic disease management perspective, the goals of P4C are to facilitate earlier identification of children with DCD and build the capacity of teachers and parents to successfully manage DCD over the long-term. In so doing, it is hypothesized that P4C will improve children’s participation (i.e., increased engagement and successful involvement) in school and at home, as well as preventing the onset of secondary consequences associated with DCD, including mental health problems [62]. As the name emphasizes, Partnering for Change is an intervention that moves away from working with individual children who have DCD to partnering and collaborating with educators and parents. The intent is to encourage successful participation by problem-solving about ways to accommodate children’s motor skill challenges through modification of their social and physical environments—for example, moving the carpet used in circle time next to the wall so children can lean against it; using nerf balls in physical education to decrease fear of being hit with the ball; changing desk and chair heights so all children are seated more securely; and encouraging diversity in school activities and leadership roles that allow children to develop different types of talents and expertise.

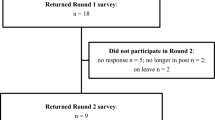

A feasibility study of P4C has been completed, and it was reported to be successful by all participants [61]. Occupational therapists who delivered this model unequivocally recommended it as a preferred method of providing service to children with DCD [63]. A large-scale implementation study is now underway to document the extent to which P4C serves to build capacity and support around the child. Individual child outcomes also are being evaluated, including psychological well-being and participation [64]. While this study is trying to alter some of the external factors that mediate mental health outcomes (e.g., social support, accommodation), other longitudinal studies are still required that will directly address the intra-personal variables that may make a child with DCD more resilient. Systematic exploration of these potentially modifiable environmental and intra-personal factors is needed before we will be ready to unequivocally answer the question of causality.

Conclusion

The pathway through which DCD influences children’s physical health and weight status is now being studied longitudinally in a population-based sample of 600 preschool children with and without DCD; it will consider factors such as family activity levels, physical fitness, participation, motivation, perceived competence, and ADHD [65]. Studies like this are also needed before we will be able to answer questions about causality and the direct or indirect pathways through which DCD impacts on mental health. The challenge to researchers is this: With such compelling evidence that many or most children with DCD experience psychological distress, should we be continuing to conduct correlational studies to examine its presence? We think not. Instead, we suggest that researchers can seek to establish causality by investigating interventions that have the potential to “interrupt” the trajectory from DCD to mental health problems. In so doing, researchers will be able to address important questions about causal pathways while simultaneously providing much needed support to children with DCD and their families. For example, longitudinal studies might include a “monitoring” or baseline period followed by the staggered introduction of an intervention that aims to change one or more factors known to be potential mediators in the psychological outcomes of children with DCD (e.g., self-esteem, social skills, and bullying). Outcomes could then be monitored over time to evaluate the extent to which intervention changes the mediator variable as well as the eventual psychological outcome (i.e., depression).

Models such as the one proposed by Cairney et al. [5, 6••] provide an ideal framework from which to explore not only the relationships among the array of factors that place children with DCD at risk for psychological problems in the first place, but also the extent to which specific interventions can alter the trajectory that is currently observed from motor coordination difficulties to mental health problems. We have suggested Partnering for Change [61] as one intervention that targets many of the potentially modifiable factors and for which empirical data are now being collected.

Without question, the literature has clearly established that many children with DCD are struggling and experiencing negative mental health outcomes. We invite other researchers to begin to think of intervention studies as a viable means of mapping trajectories and establishing causality.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. Arlington: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; 2013.

Barnett AL. Motor assessment in developmental coordination disorder: From identification to intervention. Int J Disabil Dev Educ. 2008;55:113–29. doi:10.1080/10349120802033436.

Summers J, Larkin D, Dewey D. Activities of daily living in children with developmental coordination disorder: dressing, personal hygiene, and eating skills. Hum Mov Sci. 2008;27:215–29. doi:10.1016/j.humov.2008.02.002.

Wang TN, Tseng MH, Wilson BN, Hu FC. Functional performance of children with developmental coordination disorder at home and at school. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2009;51:817–25.

Cairney J, Veldhuizen S, Szatmari P. Motor coordination and emotional-behavioral problems in children. Curr Opin Psychiatr. 2010;23:324–9. doi:10.1097/YCO.0b013e32833aa0aa.

Cairney J, Rigoli D, Piek J. Developmental coordination disorder and internalizing problems in children: the environmental stress hypothesis elaborated. Dev Rev. 2013;33:224–38. This important paper draws together current evidence and outlines a model that suggests that DCD is a primary stressor that cannot be changed and that typically leads to secondary stressors, which subsequently contribute to heightened risk of depression and anxiety. Of importance, the model posits that secondary stressors may be mediated by inter- and intra-personal factors that are potentially modifiable.

Lingam R, Jongmans MJ, Ellis M, Hunt LP, Golding J, Emond A. Mental health difficulties in children with developmental coordination disorder. Pediatrics. 2012;129:e882–91. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-1556.

Rigoli D, Piek JP, Kane R. Motor skills and psychosocial correlates in a normal adolescent sample. Pediatrics. 2012;129:e892–900. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-1237.

Wilson A, Piek JP, Kane R. An investigation of the relationship between motor ability and internalising symptoms in pre-primary children: the mediating role of social skills. Infant Child Dev. 2012;22:151–64. doi:10.1002/icd.1773.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-III-R. Arlington: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; 1987.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV. Arlington: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; 1994.

Blank R, Smits-Engelsman B, Polatajko H, Wilson P. European Academy for Childhood Disability (EACD): recommendations on the definition, diagnosis and intervention of developmental coordination disorder (long version). Dev Med Child Neurol. 2012;54:54–93. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8749.2011.04171.x. A panel of international experts synthesized evidence regarding the diagnosis and management of children with DCD—in essence, producing best-practice guidelines that are now being implemented in many European countries.

Lingam R, Hunt L, Golding J, Jongmans M, Emond A. Prevalence of developmental coordination disorder using the DSM-IV at 7 years of age: a UK population-based study. Pediatrics. 2009;123:e693–700. doi:10.1542/peds.2008-1770.

Gaines R, Missiuna C, Egan M, McLean J. Educational outreach and collaborative care enhances physician’s perceived knowledge about developmental coordination disorder. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8(1):21. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-8-21.

Rodger S, Mandich A. Getting the run around: accessing services for children with developmental co-ordination disorder. Child Care Health Dev. 2005;31:449–57. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2214.2005.00524.x.

Wilson PH, Ruddock S, Smits-Engelsman B, Polatajko H, Blank R. Understanding performance deficits in developmental coordination disorder: A meta-analysis of recent research. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2013;55:217–28. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8749.2012.04436.x. This meta-analysis provides the most comprehensive review of evidence concerning the motor skill difficulties of children with DCD. It suggests a pattern of numerous deficits in working memory, executive function, predictive control of movement, and many other areas; it also provides direction for impairment-focused research for the next several years.

Lingam R, Golding J, Jongmans MJ, Hunt LP, Ellis M, Emond A. The association between developmental coordination disorder and other developmental traits. Pediatrics. 2010;126:e1109–18. doi:10.1542/peds.2009-2789.

Roberts, G., Anderson, P. J., Davis, N., De Luca, C., Cheong, J., Doyle, L. W., & Victorian Infant Collaborative Study Group. Developmental coordination disorder in geographic cohorts of 8-year-old children born extremely preterm or extremely low birthweight in the 1990s. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2011;53:55–60. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8749.2010.03779.x.

Stephenson EA, Chesson RA. ‘Always the guiding hand’: parents’ accounts of the long-term implications of developmental co-ordination disorder for their children and families. Child Care Health Dev. 2008;34:335–43. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2214.2007.00805.x.

Cousins M, Smyth MM. Developmental coordination impairments in adulthood. Hum Mov Sci. 2003;22:433–59.

Fitzpatrick DA, Watkinson EJ. The lived experience of physical awkwardness: adults’ retrospective views. Adapt Phys Act Q. 2003;20:279–97.

Kirby A, Sugden D, Beveridge S, Edwards L. Developmental co-ordination disorder (DCD) in adolescents and adults in further and higher education. J Res Spec Ed Needs. 2008;8(3):120–31. doi:10.1111/j.1471-3802.2008.00111.x.

Missiuna C, Moll S, King G, Stewart D, Macdonald K. Life experiences of young adults who have coordination difficulties. Can J Occup Ther. 2008;75:157–66. doi:10.1177/000841740807500307.

Schott N, Alof V, Hultsch D, Meermann D. Physical fitness in children with developmental coordination disorder. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2007;78:438–50. doi:10.1080/02701367.2007.10599444.

Tsiotra GD, Nevill AM, Lane AM, Koutedakis Y. Physical fitness and developmental coordination disorder in Greek children. Pediatr Exerc Sci. 2009;21:186–95.

Cairney J, Hay JA, Veldhuizen S, Missiuna C, Faught BE. Developmental coordination disorder, sex, and activity deficit over time: a longitudinal analysis of participation trajectories in children with and without coordination difficulties. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2010;52:e67–72. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8749.2009.03520.x.

Cairney J, Kwan MYW, Hay JA, Faught BE. Developmental coordination disorder, gender, and body weight: examining the impact of participation in active play. Res Dev Disabil. 2012;33:1566–73.

Green D, Lingam R, Mattocks C, Riddoch C, Ness A, Emond A. The risk of reduced physical activity in children with probable developmental coordination disorder: a prospective longitudinal study. Res Dev Disabil. 2011;32:1332–42.

Cairney J, Hay J, Faught B, Hawes R. Developmental coordination disorder and overweight and obesity in children aged 9–14 y. Int J Obes. 2005;29:369–72. doi:10.1038/sj.ijo.0802893.

Cairney J, Hay J, Veldhuizen S, Missiuna C, Mahlberg N, Faught BE. Trajectories of relative weight and waist circumference among children with and without developmental coordination disorder. Can Med Assoc J. 2010;182:1167–72. doi:10.1503/cmaj.091454.

Wagner MO, Kastner J, Petermann F, Jekauc D, Worth A, Bös K. The impact of obesity on developmental coordination disorder in adolescence. Res Dev Disabil. 2011;32:1970–6.

Zhu YC, Wu SK, Cairney J. Obesity and motor coordination ability in Taiwanese children with and without developmental coordination disorder. Res Dev Disabil. 2011;32:801–7. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2010.10.020.

Skinner RA, Piek JP. Psychosocial implications of poor motor coordination in children and adolescents. Hum Mov Sci. 2001;20(1–2):73–94.

Wagner MO, Bös K, Jascenoka J, Jekauc D, Petermann F. Peer problems mediate the relationship between developmental coordination disorder and behavioral problems in school-aged children. Res Dev Disabil. 2012;33:2072–9.

Sylvestre A, Nadeau L, Charron L, Larose N, Lepage C. Social participation by children with developmental coordination disorder compared to their peers. Disabil Rehabil. 2013;35:1814–20. doi:10.3109/09638288.2012.756943.

Poulsen AA, Ziviani JM, Cuskelly M, Smith R. Boys with developmental coordination disorder: loneliness and team sports participation. Am J Occup Ther. 2007;61(4):451–62. doi:10.5014/ajot.61.4.451.

Campbell W, Missiuna C, Vaillancourt T. Peer victimization and depression in children with and without motor coordination difficulties. Psychol Sch. 2012;49:328–41. doi:10.1002/pits.21600.

Cocks N, Barton B, Donelly M. Self-concept of boys with developmental coordination disorder. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 2009;29:6–22. doi:10.1080/01942630802574932.

Engel-Yeger B, Hanna Kasis A. The relationship between developmental co-ordination disorders, child’s perceived self-efficacy and preference to participate in daily activities. Child Care Health Dev. 2010;36:670–7. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2214.2010.01073.x.

Poulsen AA, Johnson H, Ziviani JM. Participation, self-concept and motor performance of boys with developmental coordination disorder: a classification and regression tree analysis approach. Aust Occup Ther J. 2011;58(2):95–102. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1630.2010.00880.x.

Missiuna, C.M., Cairney, J., Pollock, N., Campbell, W., Russell, D.J., Macdonald, K., et al. Psychological distress in children with developmental coordination disorder and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Res Dev Disabil. 2014. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2014.01.007.

Piek JP, Barrett NC, Smith LM, Rigoli D, Gasson N. Do motor skills in infancy and early childhood predict anxious and depressive symptomatology at school age? Hum Mov Sci. 2010;29(5):777–86.

Piek JP, Bradbury GS, Elsley SC, Tate L. Motor coordination and social-emotional behaviour in preschool-aged children. Int J Disabil Dev Educ. 2008;55(2):143–51. doi:10.1080/10349120802033592.

Piek JP, Rigoli D, Pearsall-Jones JG, Martin NC, Hay DA, Bennett KS, et al. Depressive symptomatology in child and adolescent twins with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and/or developmental coordination disorder. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2007;10(4):587–96.

Pearsall-Jones JG, Piek JP, Rigoli D, Martin NC, Levy F. Motor disorder and anxious and depressive symptomatology: a monozygotic co-twin control approach. Res Dev Disabil. 2011. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2011.01.042.

Pratt ML, Hill EL. Anxiety profiles in children with and without developmental coordination disorder. Res Dev Disabil. 2011;32:1253–9. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2011.02.006.

Missiuna C, Gaines R, McLean J, DeLaat D, Egan M, Soucie H. Description of children identified by physicians as having developmental coordination disorder. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2008;50:839–44. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8749.2008.03140.x.

Eggleston M, Hanger N, Frampton C, Watkins W. Coordination difficulties and self-esteem: a review and findings from a New Zealand survey. Aust Occup Ther J. 2012;59:456–62. doi:10.1111/1440-1630.12007.

Rasmussen P, Gillberg C. Natural outcome of ADHD with developmental coordination disorder at age 22 years: a controlled, longitudinal, community-based study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39:1424–31. doi:10.1097/00004583-200011000-00017.

Drew S. Developmental co-ordination disorder in adults. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell; 2005.

Missiuna C, Moll S, Law M, King S, King G. Mysteries and mazes: parents’ experiences of children with developmental coordination disorder. Can J Occup Ther. 2006;73(1):7–17. doi:10.2182/cjot.05.0010.

Ahern K. “Something is wrong with my child”: a phenomenological account of a search for a diagnosis. Early Ed Dev. 2000;11:187–201.

Sugden D, Kirby A, Dunford C. Movement difficulties in children: developmental co-ordination disorder. Int J Disabil Dev Educ. 2008;55:93–6.

Dunford C, Street E, O’Connell H, Kelly J, Sibert JR. Are referrals to occupational therapy for developmental coordination disorder appropriate? Arch Dis Child. 2004;89:143–7. doi:10.1136/adc.2002.016303.

Missiuna C. (2010). Poor handwriting is only a symptom: children with developmental coordination disorder. OT Now (electronic article), (Original version published in 2002).

Kirby A, Salmon G, Edwards L. Should children with ADHD be routinely screened for motor coordination problems? The role of the paediatric occupational therapist. Br J Occup Ther. 2007;70:483–6.

Wilson BN, Neil K, Kamps PH, Babcock S. Awareness and knowledge of developmental co-ordination disorder among physicians, teachers and parents. Child Care Health Dev. 2012;39:296–300. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2214.2012.01403.x.

Bayona CL, McDougall J, Tucker MA, Nichols M, Mandich A. School-based occupational therapy for children with fine motor difficulties: evaluating functional outcomes and fidelity of services. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 2006;26:89–110. doi:10.1080/J006v26n03_07.

Reid D, Chiu T, Sinclair G, Wehrmann S, Naseer Z. Outcomes of an occupational therapy school-based consultation service for students with fine motor difficulties. Can J Occup Ther. 2006;73:215–24. doi:10.1177/000841740607300406.

Spencer KC, Turkett A, Vaughan R, Koenig S. School-based practice patterns: a survey of occupational therapists in Colorado. Am J Occup Ther. 2006;60(1):81–91. doi:10.5014/ajot.60.1.81.

Missiuna C, Pollock N, Campbell W, Bennett S, Hecimovich C, Gaines R, et al. Use of the Medical Research Council Framework to develop a complex intervention in pediatric occupational therapy: assessing feasibility. Res Dev Disabil. 2012;33:1443–52.

Missiuna C, Pollock N, Levac D, Campbell W, Sahagian Whalen S, Bennett S, et al. Partnering for Change: an innovative school-based occupational therapy service delivery model for children with developmental coordination disorder. Can J Occup Ther. 2012;79:41–50. doi:10.2182/cjot.2012.79.1.6.

Campbell WN, Missiuna CA, Rivard LM, Pollock NA. Support for everyone: experiences of occupational therapists delivering a new model of school-based service. Can J Occup Ther. 2012;79:51–9. doi:10.2182/cjot.2012.79.1.7.

Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care. $994,600 (2013-2015). Implementation and evaluation of Partnering for Change: an innovative model to transform health service provision for school-aged children with developmental coordination disorder. Missiuna, C., Pollock, N., Bennett, S., Camden, C., Campbell, W., McCauley, D., O’Reilly, D., Gaines, R., & Cairney, J.

Canadian Institutes of Health Research. $1,579,006 (2013-2018). Impact of developmental coordination disorder on the physical health of young children: a five-year study of motor coordination, physical activity, physical fitness and obesity. Cairney, J., Missiuna, C., Timmons, B.W., (Co-PIs), Howard, M., Kwan, M., Price, D., Rivard, L., Veldhuizen, S., Wade, T., Wahi, G.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

ᅟ

Conflict of Interest

Cheryl Missiuna and Wenonah N. Campbell declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Missiuna, C., Campbell, W.N. Psychological Aspects of Developmental Coordination Disorder: Can We Establish Causality?. Curr Dev Disord Rep 1, 125–131 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40474-014-0012-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40474-014-0012-8