Abstract

Purpose of Review

The integration of information across sensory modalities into unified percepts is a fundamental sensory process upon which a multitude of cognitive processes are based. We review the body of literature exploring aging-related changes in audiovisual integration published over the last 5 years. Specifically, we review the impact of changes in temporal processing, the influence of the effectiveness of sensory inputs, the role of working memory, and the newer studies of intra-individual variability during these processes.

Recent Findings

Work in the last 5 years on bottom-up influences of sensory perception has garnered significant attention. Temporal processing, a driving factors of multisensory integration, has now been shown to decouple with multisensory integration in aging, despite their co-decline with aging. The impact of stimulus effectiveness also changes with age, where older adults show maximal benefit from multisensory gain at high signal-to-noise ratios. Following sensory decline, high working memory capacities have now been shown to be somewhat of a protective factor against age-related declines in audiovisual speech perception, particularly in noise. Finally, newer research is emerging focusing on the general intra-individual variability observed with aging.

Summary

Overall, the studies of the past 5 years have replicated and expanded on previous work that highlights the role of bottom-up sensory changes with aging and their influence on audiovisual integration, as well as the top-down influence of working memory.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Sumby WH, Pollack I. Visual contribution to speech intelligibility in noise. J Acoust Soc Am. 1954;26:212–5.

Altieri N, Stevenson RA, Wallace MT, Wenger MJ. Learning to associate auditory and visual stimuli: behavioral and neural mechanisms. Brain Topogr. 2015;28(3):479–93. doi:10.1007/s10548-013-0333-7.

Sommers MS, Tye-Murray N, Spehar B. Auditory-visual speech perception and auditory-visual enhancement in normal-hearing younger and older adults. Ear Hear. 2005;26(3):263–75.

Stein B, Meredith MA. The merging of the senses. Boston: MIT Press; 1993.

Fister JK, Stevenson RA, Nidiffer AR, Barnett ZP, Wallace MT. Stimulus intensity modulates multisensory temporal processing. Neuropsychologia. 2016;88:92–100.

Stevenson RA, James TW. Audiovisual integration in human superior temporal sulcus: inverse effectiveness and the neural processing of speech and object recognition. NeuroImage. 2009;44(3):1210–23. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.09.034.

Stevenson RA, VanDerKlok RM, Pisoni DB, James TW. Discrete neural substrates underlie complementary audiovisual speech integration processes. NeuroImage. 2011;55(3):1339–45. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.12.063.

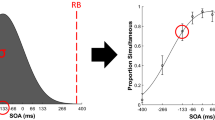

•• Stevenson RA, Baum SH, Krueger J, Newhouse PA, Wallace MT. Links between temporal acuity and multisensory integration across life span. 2017. This study demonstrated the co-occuring decline in temporal processing and perceptual binding of speech signals. Importantly, these processes, while coupled during development, become decoupled during healthy aging. Also see 72.

Stevenson RA, Fister JK, Barnett ZP, Nidiffer AR, Wallace MT. Interactions between the spatial and temporal stimulus factors that influence multisensory integration in human performance. Exp Brain Res Exp Hirnforsch. 2012; doi:10.1007/s00221-012-3072-1.

Stevenson RA, Segers M, Ncube BL, Black KR, Bebko JM, Ferber S et al. The cascading influence of low-level multisensory processing on speech perception in autism. 2017. doi:10.1177/1362361317704413.

Meredith MA, Nemitz JW, Stein BE. Determinants of multisensory integration in superior colliculus neurons. I. Temporal factors. J Neurosci. 1987;7(10):3215–29.

Meredith MA, Wallace MT, Stein BE. Visual, auditory and somatosensory convergence in output neurons of the cat superior colliculus: multisensory properties of the tecto-reticulo-spinal projection. Exp Brain Res Exp Hirnforsch. 1992;88(1):181–6.

Royal DW, Carriere BN, Wallace MT. Spatiotemporal architecture of cortical receptive fields and its impact on multisensory interactions. Exp Brain Res Exp Hirnforsch. 2009;198(2–3):127–36. doi:10.1007/s00221-009-1772-y.

Meredith MA, Stein BE. Spatial factors determine the activity of multisensory neurons in cat superior colliculus. Brain Res. 1986;365(2):350–4.

Senkowski D, Talsma D, Grigutsch M, Herrmann CS, Woldorff MG. Good times for multisensory integration: effects of the precision of temporal synchrony as revealed by gamma-band oscillations. Neuropsychologia. 2007;45(3):561–71.

Schall S, Quigley C, Onat S, Konig P. Visual stimulus locking of EEG is modulated by temporal congruency of auditory stimuli. Exp Brain Res Exp Hirnforsch. 2009;198(2–3):137–51. doi:10.1007/s00221-009-1867-5.

Macaluso E, George N, Dolan R, Spence C, Driver J. Spatial and temporal factors during processing of audiovisual speech: a PET study. NeuroImage. 2004;21(2):725–32.

Miller LM, D'Esposito M. Perceptual fusion and stimulus coincidence in the cross-modal integration of speech. J Neurosci. 2005;25(25):5884–93.

Conrey B, Pisoni DB. Auditory-visual speech perception and synchrony detection for speech and nonspeech signals. J Acoust Soc Am. 2006;119(6):4065–73.

Dixon NF, Spitz L. The detection of auditory visual desynchrony. Perception. 1980;9(6):719–21.

Hillock AR, Powers AR, Wallace MT. Binding of sights and sounds: age-related changes in multisensory temporal processing. Neuropsychologia. 2011;49(3):461–7. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2010.11.041.

Keetels M, Vroomen J. The role of spatial disparity and hemifields in audio-visual temporal order judgments. Exp Brain Res Exp Hirnforsch. 2005;167(4):635–40. doi:10.1007/s00221-005-0067-1.

Powers AR 3rd, Hillock AR, Wallace MT. Perceptual training narrows the temporal window of multisensory binding. J Neurosci. 2009;29(39):12265–74. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3501-09.2009.

van Atteveldt NM, Formisano E, Blomert L, Goebel R. The effect of temporal asynchrony on the multisensory integration of letters and speech sounds. Cereb Cortex. 2007;17(4):962–74. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhl007.

van Wassenhove V, Grant KW, Poeppel D. Temporal window of integration in auditory-visual speech perception. Neuropsychologia. 2007;45(3):598–607. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2006.01.001.

Zampini M, Guest S, Shore DI, Spence C. Audio-visual simultaneity judgments. Percept Psychophys. 2005;67(3):531–44.

Wallace MT, Roberson GE, Hairston WD, Stein BE, Vaughan JW, Schirillo JA. Unifying multisensory signals across time and space. Exp Brain Res Exp Hirnforsch. 2004;158(2):252–8. doi:10.1007/s00221-004-1899-9.

Nidiffer AR, Stevenson RA, Fister JK, Barnett ZP, Wallace MT. Interactions between space and effectiveness in human multisensory performance. Neuropsychologia. 2016;88:83–91.

Bertelson P, Frissen I, Vroomen J, de Gelder B. The aftereffects of ventriloquism: patterns of spatial generalization. Percept Psychophys. 2006;68(3):428–36.

Bertelson P, Radeau M. Cross-modal bias and perceptual fusion with auditory-visual spatial discordance. Percept Psychophys. 1981;29(6):578–84.

Colonius H, Diederich A, Steenken R. Time-window-of-integration (TWIN) model for saccadic reaction time: effect of auditory masker level on visual-auditory spatial interaction in elevation. Brain Topogr. 2009;21(3–4):177–84. doi:10.1007/s10548-009-0091-8.

Frens MA, Van Opstal AJ, Van der Willigen RF. Spatial and temporal factors determine auditory-visual interactions in human saccadic eye movements. Percept Psychophys. 1995;57(6):802–16.

Lewald J, Guski R. Cross-modal perceptual integration of spatially and temporally disparate auditory and visual stimuli. Brain Res Cogn Brain Res. 2003;16(3):468–78.

Munhall K, Vatikiotis-Bateson E. Spatial and temporal constraints on audiovisual speech perception. In: Calvert G, Spence C, Stein BE, editors. The handbook of multisensory processes. Cambridge: MIT Press; 2004. p. 177–88.

Sarko DK, Nidiffer AR, Powers IA, Ghose D, Hillock-Dunn A, Fister MC et al. Spatial and temporal features of multisensory processes: bridging animal and human studies. In: Murray MM, Wallace MT, editors. The Neural Bases of Multisensory Processes. Frontiers in Neuroscience. Boca Raton (FL) 2012.

James TW, Kim S, Stevenson RA, editors. Assessing multisensory interaction with additive factors and functional MRI. The International Society for Psychophysics; 2009; Galway, Ireland.

James TW, Stevenson RA. The Use of fMRI to Assess Multisensory Integration. In: Murray MM, Wallace MT, editors. The Neural Bases of Multisensory Processes. Frontiers in Neuroscience. Boca Raton (FL) 2012.

James TW, Stevenson RA, Kim S. Inverse effectiveness in multisensory processing. In: Stein BE, editor. The new handbook of multisensory processes. Cambridge: MIT Press; 2012.

Kim S, Stevenson RA, James TW. Visuo-haptic neuronal convergence demonstrated with an inversely effective pattern of BOLD activation. J Cogn Neurosci. 2012;24(4):830–42. doi:10.1162/jocn_a_00176.

Stevenson R, Bushmakin M, Kim S, Wallace M, Puce A, James T. Inverse effectiveness and multisensory interactions in visual event-related potentials with audiovisual speech. Brain Topography. 2012:1–19. doi:10.1007/s10548-012-0220-7.

Stevenson RA, Geoghegan ML, James TW. Superadditive BOLD activation in superior temporal sulcus with threshold non-speech objects. Exp Brain Res. 2007;179(1):85–95.

Stevenson RA, Kim S, James TW. An additive-factors design to disambiguate neuronal and areal convergence: measuring multisensory interactions between audio, visual, and haptic sensory streams using fMRI. Exp Brain Res. 2009;198(2–3):183–94. doi:10.1007/s00221-009-1783-8.

Senkowski D, Saint-Amour D, Hofle M, Foxe JJ. Multisensory interactions in early evoked brain activity follow the principle of inverse effectiveness. NeuroImage. 2011; doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.03.075.

Tye-Murray N, Sommers M, Spehar B, Myerson J, Hale S. Aging, audiovisual integration, and the principle of inverse effectiveness. Ear Hear. 2010;31(5):636–44. doi:10.1097/AUD.0b013e3181ddf7ff.

Meredith MA, Stein BE. Visual, auditory, and somatosensory convergence on cells in superior colliculus results in multisensory integration. J Neurophysiol. 1986;56(3):640–62.

Carriere BN, Royal DW, Wallace MT. Spatial heterogeneity of cortical receptive fields and its impact on multisensory interactions. J Neurophysiol. 2008;

Krueger J, Royal DW, Fister MC, Wallace MT. Spatial receptive field organization of multisensory neurons and its impact on multisensory interactions. Hearing Res. 2009;258(1–2):47–54. doi:10.1016/j.heares.2009.08.003.

Royal DW, Carriere BN, Wallace MT. Spatiotemporal architecture of cortical receptive fields and its impact on multisensory interactions. Exp Brain Res. 2009;198(2–3):127–36. doi:10.1007/s00221-009-1772-y.

Ma WJ, Zhou X, Ross LA, Foxe JJ, Parra LC. Lip-reading aids word recognition most in moderate noise: a Bayesian explanation using high-dimensional feature space. PLoS One. 2009;4(3):e4638.

Ross LA, Molholm S, Blanco D, Gomez-Ramirez M, Saint-Amour D, Foxe JJ. The development of multisensory speech perception continues into the late childhood years. Eur J Neurosci. 2011;33(12):2329–37. doi:10.1111/j.1460-9568.2011.07685.x.

Ross LA, Saint-Amour D, Leavitt VM, Javitt DC, Foxe JJ. Do you see what I am saying? Exploring visual enhancement of speech comprehension in noisy environments. Cereb Cortex. 2007;17(5):1147–53. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhl024.

Vroomen J, Keetels M. Perception of intersensory synchrony: a tutorial review. Atten Percept Psychophys. 2010;72(4):871–84. doi:10.3758/APP.72.4.871.

Stevenson RA, Zemtsov RK, Wallace MT. Individual differences in the multisensory temporal binding window predict susceptibility to audiovisual illusions. J Exp Psychol Hum Percept Perform. 2012;38(6):1517–29. doi:10.1037/a0027339.

• Mozolic JL, Hugenschmidt CE, Peiffer AM, Laurienti PJ. Multisensory integration and aging. 2012. This chapter provides an excellent summary of multisensory processing in aging.

Diederich A, Colonius H, Schomburg A. Assessing age-related multisensory enhancement with the time-window-of-integration model. Neuropsychologia. 2008;46(10):2556–62.

Setti A, Burke KE, Kenny RA, Newell FN. Is inefficient multisensory processing associated with falls in older people? Exp Brain Res. 2011;209(3):375–84.

Setti A, Finnigan S, Sobolewski R, McLaren L, Robertson IH, Reilly RB, et al. Audiovisual temporal discrimination is less efficient with aging: an event-related potential study. Neuroreport. 2011;22(11):554–8.

• Chan YM, Pianta MJ, McKendrick AM. Reduced audiovisual recalibration in the elderly. Frontiers in aging neuroscience. 2014; 6. This study is the first to show a decrease in multisensory plasticity in older adults relative to younger adults.

Chan YM, Pianta MJ, McKendrick AM. Older age results in difficulties separating auditory and visual signals in time. J Vis. 2014;14(11):13.

Hay-McCutcheon MJ, Pisoni DB, Hunt KK. Audiovisual asynchrony detection and speech perception in hearing-impaired listeners with cochlear implants: a preliminary analysis. Int J Audiol. 2009;48(6):321–33. doi:10.1080/14992020802644871.

Stevenson RA, Wallace MT. Multisensory temporal integration: task and stimulus dependencies. Exp Brain Res Exp Hirnforsch. 2013;227(2):249–61. doi:10.1007/s00221-013-3507-3.

van Eijk RL, Kohlrausch A, Juola JF, van de Par S. Audiovisual synchrony and temporal order judgments: effects of experimental method and stimulus type. Percept Psychophys. 2008;70(6):955–68.

Colonius H, Diederich A. Multisensory interaction in saccadic reaction time: a time-window-of-integration model. J Cogn Neurosci. 2004;16(6):1000–9. doi:10.1162/0898929041502733.

Stevenson RA, Ghose D, Fister JK, Sarko DK, Altieri NA, Nidiffer AR, et al. Identifying and quantifying multisensory integration: a tutorial review. Brain Topogr. 2014; doi:10.1007/s10548-014-0365-7.

McGurk H, MacDonald J. Hearing lips and seeing voices. Nature. 1976;264(5588):746–8.

Shams L, Kamitani Y, Shimojo S. Illusions. What you see is what you hear. Nature. 2000;408(6814):788.

Sekuler R, Sekuler A, Lau R. Sound changes perception of visual motion. Nature. 1997;384:308–9.

• DeLoss DJ, Pierce RS, Andersen GJ. Multisensory integration, aging, and the sound-induced flash illusion. Psychol Aging. 2013;28(3):802. This study showed increased binding of audiovisual stimuli at wide temporal offsets, highlighting the link between temporal processing and perceptual binding in older adults. Additionally, this study suggested an association between larger TBWs and increased levels of falls in older adults.

• McGovern DP, Roudaia E, Stapleton J, McGinnity TM, Newell FN. The sound-induced flash illusion reveals dissociable age-related effects in multisensory integration. Frontiers in aging neuroscience. 2014;6:250. This study highlighted that changes in multisensory integration with aging are related to changes in perceptual sensitivity explicitly. Also see 72.

• Setti A, Burke KE, Kenny R, Newell FN. Susceptibility to a multisensory speech illusion in older persons is driven by perceptual processes. Frontiers in psychology. 2013;4. This study highlighted that changes in multisensory integration with aging are related to changes in perceptual sensitivity explicitly. Also see 71.

•• Bedard G, Barnett-Cowan M. Impaired timing of audiovisual events in the elderly. Exp Brain Res. 2016;234(1):331–40. This study demonstrated the co-occuring decline in temporal processing and perceptual binding of simple sensory signals. Importantly, these processes become decoupled during healthy aging. Also see 8.

Hillock-Dunn A, Wallace MT. Developmental changes in the multisensory temporal binding window persist into adolescence. Dev Sci. 2012;15(5):688–96. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7687.2012.01171.x.

Fujisaki W, Shimojo S, Kashino M, Nishida S. Recalibration of audiovisual simultaneity. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7(7):773–8. doi:10.1038/nn1268.

Vroomen J, Keetels M, de Gelder B, Bertelson P. Recalibration of temporal order perception by exposure to audio-visual asynchrony. Brain Res Cogn Brain Res. 2004;22(1):32–5. doi:10.1016/j.cogbrainres.2004.07.003.

Noel JP, De Niear MA, Stevenson R, Alais D, Wallace MT. Atypical rapid audio-visual temporal recalibration in autism spectrum disorders. Autism Research. 2016.

Van der Burg E, Alais D, Cass J. Rapid recalibration to audiovisual asynchrony. J Neurosci. 2013;33(37):14633–7.

Van der Burg E, Goodbourn PT. Rapid, generalized adaptation to asynchronous audiovisual speech. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2015;282(1804):20143083.

Powers AR 3rd, Hevey MA, Wallace MT. Neural correlates of multisensory perceptual learning. J Neurosci. 2012;32(18):6263–74. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6138-11.2012.

Stevenson RA, Wilson MM, Powers AR, Wallace MT. The effects of visual training on multisensory temporal processing. Exp Brain Res Exp Hirnforsch. 2013;225(4):479–89. doi:10.1007/s00221-012-3387-y.

Schlesinger JJ, Stevenson RA, Shotwell MS, Wallace MT. Improving pulse oximetry pitch perception with multisensory perceptual training. Anesth Analg. 2014;118(6):1249–53. doi:10.1213/ANE.0000000000000222.

•• Setti A, Stapleton J, Leahy D, Walsh C, Kenny RA, Newell FN. Improving the efficiency of multisensory integration in older adults: audio-visual temporal discrimination training reduces susceptibility to the sound-induced flash illusion. Neuropsychologia. 2014;61:259–68. This study provided novel evidence that sensory training paradigms in older adults may be able to improve temporal perception, and that these improvements may generalize to changes in multisenosry integration.

Ross LA, Saint-Amour D, Leavitt VM, Molholm S, Javitt DC, Foxe JJ. Impaired multisensory processing in schizophrenia: deficits in the visual enhancement of speech comprehension under noisy environmental conditions. Schizophr Res. 2007;97(1–3):173–83. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2007.08.008.

Foxe JJ, Molholm S, Del Bene VA, Frey H-P, Russo NN, Blanco D et al. Severe multisensory speech integration deficits in high-functioning school-aged children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and their resolution during early adolescence. Cerebral Cortex. 2013:bht213.

Stevenson RA, Baum SH, Segers M, Ferber S, Barense MD, Wallace MT. Multisensory speech perception in autism spectrum disorder: from phoneme to whole-word perception. Autism Res. 2017;

• Stevenson RA, Nelms CE, Baum SH, Zurkovsky L, Barense MD, Newhouse PA, et al. Deficits in audiovisual speech perception in normal aging emerge at the level of whole-word recognition. Neurobiol Aging. 2015;36(1):283–91. doi:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.08.003. This study showed that declines in multisensory integration of speech signals in older adults is more pronounced at higher levels of the speech-processing hierarchy.

•• Jansen SD, Keebler JR, Chaparro A. Shifts in maximum audiovisual integration with age. Multisensory Research. In Press. This study showed that the signal-to-noise level at which older adults obtain maximal multisensory gain is shifted higher (less noise) relative to younger adults. Importantly, this shift was linked explicitly to declines in working memory, providing a novel link between sensory perception and cognitive abilities in aging.

• Tye-Murray N, Spehar B, Myerson J, Hale S, Sommers M. Lipreading and audiovisual speech recognition across the adult lifespan: implications for audiovisual integration. Psychol Aging. 2016;31(4):380. This study highlights in increased importance that visual acuity has on the ability of older adults to make use of multisensory benefits. Also see 90 and 91.

Gordon MS, Allen S. Audiovisual speech in older and younger adults: integrating a distorted visual signal with speech in noise. Exp Aging Res. 2009;35(2):202–19.

• Diaconescu AO, Hasher L, McIntosh AR. Visual dominance and multisensory integration changes with age. NeuroImage. 2013;65:152–66. This study highlights in increased importance that visual acuity has on the ability of older adults to make use of multisensory benefits. Also see 88 and 91.

•• Sekiyama K, Soshi T, Sakamoto S. Enhanced audiovisual integration with aging in speech perception: a heightened McGurk effect in older adults. Multisensory and sensorimotor interactions in speech perception. 2015:237. This study highlights in increased importance that visual acuity has on the ability of older adults to make use of multisensory benefits. Importantly, this finding persisted even after accounting for age-related hearing loss. Also see 88 and 90.

Akeroyd MA. Are individual differences in speech reception related to individual differences in cognitive ability? A survey of twenty experimental studies with normal and hearing-impaired adults. Int J Audiol. 2008;47(sup2):S53–71.

Rönnberg J, Rudner M, Lunner T, Zekveld AA. When cognition kicks in: working memory and speech understanding in noise. Noise Health. 2010;12(49):263.

Kjellberg A, Ljung R, Hallman D. Recall of words heard in noise. Appl Cogn Psychol. 2008;22(8):1088–98.

Engle RW. Working memory capacity as executive attention. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2002;11(1):19–23.

Maguinness C, Setti A, Burke K, Kenny RA, Newell FN. The effect of combined sensory and semantic components on audio-visual speech perception in older adults. Front Aging Neurosci. 2011;3:19.

Ten Oever S, Sack AT, Wheat KL, Bien N, Van Atteveldt N. Audio-visual onset differences are used to determine syllable identity for ambiguous audio-visual stimulus pairs. Front Psychol. 2013;4

Stevenson RA, Wallace MT, Altieri N. The interaction between stimulus factors and cognitive factors during multisensory integration of audiovisual speech. Front Psychol. 2014;5:352. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00352.

Frtusova JB, Winneke AH, Phillips NA. ERP evidence that auditory–visual speech facilitates working memory in younger and older adults. Psychol Aging. 2013;28(2):481.

•• Frtusova JB, Phillips NA. The auditory-visual speech benefit on working memory in older adults with hearing impairment. frontiers in psychology. 2016;7. This study of working memory showed that older adults’ with poorer hearing benefitted more from the inclusion of visual information than did those with better hearing - an effect most pronounced at the highest WM load. Thus, it appears not only that high WMC may influence multisensory integration of speech, but that multisensory integration of speech benefits WMC.

Besser J, Koelewijn T, Zekveld AA, Kramer SE, Festen JM. How linguistic closure and verbal working memory relate to speech recognition in noise—a review. Trends in amplification. 2013;17(2):75–93.

Janse E, Jesse A. Working memory affects older adults’ use of context in spoken-word recognition. Q J Exp Psychol. 2014;67(9):1842–62.

Peich M-C, Husain M, Bays PM. Age-related decline of precision and binding in visual working memory. Psychol Aging. 2013;28(3):729.

Borella E, Cantarella A, Joly E, Ghisletta P, Carbone E, Coraluppi D et al. Performance-based everyday functional competence measures across the adult lifespan: the role of cognitive abilities. International Psychogeriatrics. 2017:1–11.

Jenkins L, Myerson J, Joerding JA, Hale S. Converging evidence that visuospatial cognition is more age-sensitive than verbal cognition. Psychol Aging. 2000;15(1):157.

Cerella J, Hale S. The rise and fall in information-processing rates over the life span. Acta Psychol. 1994;86(2):109–97.

Wong NM, Ma EP-W, Lee TM. The integrity of the corpus callosum mitigates the impact of blood pressure on the ventral attention network and information processing speed in healthy adults. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience. 2017;9.

Hultsch DF, MacDonald SW, Dixon RA. Variability in reaction time performance of younger and older adults. J Gerontol Ser B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2002;57(2):P101–P15.

West R, Murphy KJ, Armilio ML, Craik FI, Stuss DT. Lapses of intention and performance variability reveal age-related increases in fluctuations of executive control. Brain Cogn. 2002;49(3):402–19.

MacDonald SW, Karlsson S, Rieckmann A, Nyberg L, Bäckman L. Aging-related increases in behavioral variability: relations to losses of dopamine D1 receptors. J Neurosci. 2012;32(24):8186–91.

Haynes B, Kliegel M, Zimprich D, Bunce D. Intraindividual reaction time variability predicts prospective memory failures in older adults. Aging Neuropsychol Cognit. 2016:1–14.

• Sugarman MA, Woodard JL, Nielson KA, Smith JC, Seidenberg M, Durgerian S, et al. Performance variability during a multitrial list-learning task as a predictor of future cognitive decline in healthy elders. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2014;36(3):236–43. Older adults were tested with a variety of cognitive tests at a baseline and an 18 month followup session, during which they were classified as cognitively stable (similar performance across time points) or declining. Variability from trial to trial of a list-learning task showed greater predictive value of later cognitive decline than overall task performance, demonstrating that trial to trial variability may precede cognitive impairment.

Troyer AK, Vandermorris S, Murphy KJ. Intraindividual variability in performance on associative memory tasks is elevated in amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Neuropsychologia. 2016;90:110–6.

Hecox K, Galambos R. Brain stem auditory evoked responses in human infants and adults. Arch Otolaryngol. 1974;99(1):30–3.

•• Anderson S, Parbery-Clark A, White-Schwoch T, Kraus N. Aging affects neural precision of speech encoding. J Neurosci. 2012;32(41):14156–64. This study investigated the timing fidelity of early, subcortical processing of speech information using the auditory brainstem response (ABR). The results indicated that the ABR to speech in older adults is delayed, diminished in amplitude, and more variable trial to trial, compared to younger adults. These differences may propogate through the processing heirarchy and contribute to difficulties in speech processing in aging.

Anderson S, Parbery-Clark A, Yi H-G, Kraus N. A neural basis of speech-in-noise perception in older adults. Ear Hear. 2011;32(6):750.

•• Baum SH, Beauchamp MS. Greater BOLD variability in older compared with younger adults during audiovisual speech perception. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e111121. This study demonstrated that trial to trial variability in response amplitude to clear, audiovisual speech syllables is increased in older adults, despite no differences in mean response amplitudes, compared to younger adults. This increase in neural variability was noted without any differences in performance on a syllable recognition task, but was hypothesized as a possible mechanism for poor speech in noise performance noted in older adults.

D'Esposito M, Zarahn E, Aguirre GK, Rypma B. The effect of normal aging on the coupling of neural activity to the bold hemodynamic response. NeuroImage. 1999;10(1):6–14.

Huettel SA, Singerman JD, McCarthy G. The effects of aging upon the hemodynamic response measured by functional MRI. NeuroImage. 2001;13(1):161–75.

Leal SL, Noche JA, Murray EA, Yassa MA. Age-related individual variability in memory performance is associated with amygdala-hippocampal circuit function and emotional pattern separation. Neurobiol Aging. 2017;49:9–19.

Zheng L, Gao Z, Xiao X, Ye Z, Chen C, Xue G. Reduced fidelity of neural representation underlies episodic memory decline in normal aging. Cerebral Cortex. 2017:1–14.

Bidelman GM, Villafuerte JW, Moreno S, Alain C. Age-related changes in the subcortical–cortical encoding and categorical perception of speech. Neurobiol Aging. 2014;35(11):2526–40.

Garrett DD, Kovacevic N, McIntosh AR, Grady CL. The importance of being variable. J Neurosci. 2011;31(12):4496–503.

• Nomi JS, Bolt TS, Ezie CC, Uddin LQ, Heller AS. Moment-to-moment BOLD signal variability reflects regional changes in neural flexibility across the lifespan. J Neurosci. 2017;37(22):5539–48. This study examined variability in resting state fMRI locally across several regions of interest in older adults and younger adults. The data showed two separate trajectories with aging—with one network showing decreased variability in aging (perhaps indicative of reduced neural flexibility) as well as increased variability across different networks.

Acknowledgements

Support for SHB was provided by Autism Speaks Meixner Postdoctoral Fellowship (#9717). RAS is funded by NSERC Discovery Grant (RGPIN-2017-04656), SSHRD Insight Grant (435-2017-0936), and the University of Western Ontario Faculty Development Research Fund.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Sarah H. Baum and Ryan Stevenson declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Geropsychiatry &; Cognitive Disorders of Late Life

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Baum, S.H., Stevenson, R.A. Shifts in Audiovisual Processing in Healthy Aging. Curr Behav Neurosci Rep 4, 198–208 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40473-017-0124-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40473-017-0124-7