Abstract

Background

A growing body of research has identified health-related quality-of-life effects for caregivers and family members of ill patients (i.e. ‘spillover effects’), yet these are rarely considered in cost-effectiveness analyses (CEAs).

Objective

The objective of this study was to catalog spillover-related health utilities to facilitate their consideration in CEAs.

Methods

We systematically reviewed the medical and economic literatures (MEDLINE, EMBASE, and EconLit, from inception through 3 April 2018) to identify articles that reported preference-based measures of spillover effects. We used keywords for utility measures combined with caregivers, family members, and burden.

Results

Of 3695 articles identified, 80 remained after screening: 8 (10%) reported spillover utility per se, as utility or disutility (i.e. utility loss); 25 (30%) reported a comparison group, either population values (n = 9) or matched, non-caregiver/family member or unaffected individuals’ utilities (n = 16; 3 reported both spillover and a comparison group); and 50 (63%) reported caregiver/family member utilities only. Alzheimer’s disease/dementia was the most commonly studied disease/condition, and the EQ-5D was the most commonly used measurement instrument.

Conclusions

This comprehensive catalog of utilities showcases the spectrum of diseases and conditions for which caregiver and family members’ spillover effects have been measured, and the variation in measurement methods used. In general, utilities indicated a loss in quality of life associated with being a caregiver or family member of an ill relative. Most studies reported caregiver/family member utility without any comparator, limiting the ability to infer spillover effects. Nevertheless, these values provide a starting point for considering spillover effects in the context of CEA, opening the door for more comprehensive analyses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Inclusion of caregiver and family member (‘spillover’) quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) in cost-effectiveness analyses (CEAs) is recommended by multiple national guidance bodies. |

Caregiver and family member QALYs can include spillover utilities (the independent utility loss due to a family member’s illness) that are rarely reported in the literature; more common are caregivers’/family members’ utilities, sometimes in combination with a comparator utility. |

Research gaps remain in spillover effect estimation and incorporation methods, slowing the adoption of these additional measures of burden into cost-effectiveness evaluations. |

1 Background

The burden of family caregiving is familiar to most [1]. Spouses’ health declines when their partners are hospitalized [2], adult children become anxious and fatigued caring for parents with dementia [3], and parents lose sleep while caring for disabled children [4]. Yet the consequences of illness in a family are in fact a complicated interplay of the physical, psychological, and emotional, ranging from strain, grief, and guilt, to gratification, interdependence, and joy, and affect caregiving as well as non-caregiving members [5]. While some families experience solace and relief when their relative’s health improves, changes in family dynamics and caregiving responsibilities may come as well: extended life for an elderly frail parent incurs extended caretaking needs; successful treatment for a severely ill child may result in a lifelong disability, with the associated care needs and emotional trauma for the parents [5,6,7]. The shifting locus of care to outpatient settings and the home increases families’ involvement in care, and the corresponding effects on their health and well-being [1].

Current recommendations for societal perspective economic evaluation include both patients’ and family members’ effects in assessing the cost effectiveness of health technologies and interventions [8,9,10,11]. The effects, both health and otherwise, that are incurred by caregivers and non-caregiving family members (hereafter called ‘spillover effects’) are challenging, both to measure and to incorporate into cost-effectiveness analysis (CEAFootnote 1). Measures of health-related spillover effects include utility valuations, via direct or indirect utility elicitation techniques, used to calculate quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs), and valuations that adopt a broader perspective, including care-related effects, that cannot be used for QALYs but rather capture the value assigned to the caring experience [12, 13]. A recommended, QALY-based measurement approach that is suitable across the variations in effects, including patient diseases/conditions, patient/caregiver/family member relationship, and extent of caregiver/family member involvement, has yet to be identified. Moreover, incorporating spillover effects into CEA poses its own challenges; although frameworks have been proposed, questions remain and inclusion has not yet become the norm [14,15,16].

The costs incurred in the course of providing informal care are also recommended for inclusion in societal perspective CEAs [9]. The time and effort of caregiving are also ‘spillover’ effects of illness, but are included on the cost side of the CEA equation. While out-of-pocket expenses and time spent caregiving are relatively simple to quantify, assigning value to time is more daunting. Multiple valuation approaches have been proposed without clear guidance for a preferred method [17, 18]. Including informal time costs in CEA is becoming more common, although it is still the exception [17, 19]. This review focuses exclusively on QALY-related spillover effects, and readers are referred elsewhere for considerations of cost spillovers [17, 18].

This review presents health utilities associated with caregivers and family members of individuals with health conditions and diseases—including spillover utilities and disutilities,Footnote 2 and caregiver and family member utilities, reported with and without comparator utilities. We also included preference-based, caregiver-specific utilities (i.e. spillover effects measured from the perspective of caregivers’ experiences and including domains other than health), although these are not consistent with a QALY framework [20]. This compilation serves two functions. First, it provides a state-of-the-field overview of preference-based measures of caregivers’ and family members’ health-related quality of life, and second, it provides a catalog of the available data from which caregiver and family member QALYs may be derived to inform CEAs. Our primary goal for this review was to inform the inclusion of spillover effects in CEAs. Secondarily, we sought to advance the methods of spillover valuation and incorporation by expanding the collective knowledge base of measurement techniques, data, and, subsequently, evaluations that include spillover effects.

2 Methods

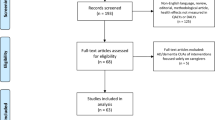

Our objective was to report the universe of articles that reported a preference-based measure of caregiver or family member spillover effects. We conducted a systematic review of the medical and economic literatures to identify articles containing utilities for family caregivers and non-caregiving family members, including three electronic databases: MEDLINE, EMBASE, and EconLit. We refined search terms by testing them against a set of known-to-us papers to ensure capture of relevant articles. The final search strategy combined terms describing utility measures with terms describing caregivers, family members, and burden: utility, disutility, preference weight, QALY, standard gamble, time trade-off, EuroQoL (EQ-5D), Short-Form 6-Dimension (SF-6D), Health Utilities Index (HUI), Quality of Wellbeing Scale (QWB), CarerQol, Carer Experience Scale (CES), Child Health Utility-9 dimensions (CHU-9D), and variants thereof; spillover, caregiver, family, partner, spouse, child, sibling, parent, grandparent, next of kin, burden, consequence, and associated variants. Figure 1 shows the search process (the full search specifications are included in the online supplementary material).

PRISMA diagram of the search process. *Examples of search terms: [spillover, caregivers, family, partner, spouse, parent, child, sibling, grandparent, next of kin, burden, impact, consequences] AND [utility, disutility, preference weight, standard gamble, time trade-off, visual analog, QALY, SF-6D, EQ-5D, CarerQol, CES, HUI, QWB, CHU-9D]. **No caregiver or family member utility reported (n = 75); duplicate (n = 12); invalid score (utility reported > 1.0 or as WTP utility; n = 4); no English full-text available (n = 4); not peer-reviewed (n = 2). PRISMA Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses, QALY quality-adjusted life-year, SF-6D Short-Form 6-Dimension, EQ-5D EuroQol-5 dimensions, CES Carer Experience Scale, HUI Health Utilities Index, QWB Quality of Wellbeing Scale, CHU-9D Child Health Utility-9 dimensions, WTP willingness to pay

2.1 Eligibility Criteria

We included peer-reviewed articles published in English that reported a preference-based measure of caregiver or family member utility or disutility, including caregiver-focused measures for which population tariffs exist (i.e., CarerQol [20] and CES [21]), from the inception of each database through 3 April 2018. We included articles that reported on multiple patient diseases and/or using multiple preference-based methods/instruments, but excluded articles that reported only the EQ-VAS or a visual analog scale measure unless the scores were transformed into utilities using a known algorithm [22].

We defined family member as anyone identified as having a familial relationship to the patient regardless of distance (e.g., cousins would meet our inclusion criterion). We assumed that all family members classified in articles as caregivers were such; we did not impose any criteria on this role. We included articles reporting on ‘informal caregivers’ unless they were described as exclusively non-familial, such as neighbors, church members, and the like, but excluded paid caregivers.

We included articles reporting on all patient diseases and conditions, including those that specified no disease, meaning they included caregivers regardless of the patient’s disease. We also included articles reporting on patient health states, defined as a distinct phase of a disease or condition (such as chemotherapy or hospitalization); a disease was defined as a diagnosed condition. We excluded disease transmission among family members from our definition of spillover effects. We included death as a health state when it was directly related to a disease or condition, such as maternal mortality, but we did not specifically search for bereavement. We imposed no age limit on patients or caregivers/family members.

We included articles reporting on studies specifically designed to measure spillover utility, those measuring caregiver/family member utility among other outcomes, and caregiver or patient interventions that included utility as an outcome. We excluded reviews, reports, study protocols, commentaries, editorials, and conference papers, as well as articles that reported what appeared to be invalid utilities, such as scores > 1.0 or those described as ‘WTP utilities’.

2.2 Data Collection

After excluding duplicates, two authors (EW and LJ) independently screened titles and abstracts; conflicts were resolved by consensus. We repeated this process with the full-text articles remaining after screening. We recorded the reason for each exclusion using Covidence systematic review software (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, VIC, Australia).

We extracted data that would allow a reader to identify potentially useful values for an analysis: patients’ disease/condition; patients’ age (adult/child/either); valuation measure used (EQ-5D, standard gamble, etc.); sample source (e.g., medical centers, patient association, population); country of sample; affected person’s role (i.e., family member/family caregiver/informal caregiver); caregiver/family member age (mean or other summary measure); sample size; utility (mean or median); if relevant to study design: comparison group source, sample size, and utility (mean or median); and if relevant, the reporting of utilities by strata, and other notes. We created a table entry for each patient disease/condition for which a relevant utility was reported in an article; articles that reported utility for more than one patient disease/condition were included in an entry for each. We included multiple utilities measured using different methods (e.g., HUI2 and HUI3) or applying different valuation weights for the same measure (e.g., Canadian and US weights for SF-6D) in one entry. If both caregiver/family member utilities and spillover disutilities were reported, we included each. If utilities were reported for the same condition/disease for multiple countries, we reported the one with the largest country-specific sample size. For all other instances of multiple utilities reported for the same disease/condition, we included those we deemed most salient to most readers and noted the availability of others in the ‘notes’ comment. We included the scores/values as reported by authors, but performed no manipulations or calculations on reported data. We grouped the entries into three categories: (1) spillover utilities or disutilities; (2) caregiver and/or family member utility reported with a matched or population comparison group; and (3) caregiver and/or family member utility reported alone.

3 Results

Our search yielded 5205 records. After removing duplicates, we screened 3695 studies by title and abstract, and assessed 177 full-text articles for eligibility; 80 articles remained for inclusion in our review (Fig. 1). Of these 80 articles, 8 (10%) reported spillover utility/disutility: 4 reported spillover disutility as the difference between population utility and the observed family caregiver utility [23,24,25,26], 1 reported disutilities only [27], 1 reported both the difference between the observed caregiver utility and the population utility, as well as a utility for a hypothetical scenario in which the ill relative did not need caregiving [28], and 2 reported spillover utilities only, elicited using a direct method to isolate the spillover effect per se [29, 30]. Twenty-five (30%) reported a comparison group, either general population norms (n = 9; 3 of which also reported disutility) (Table 1) or matched, non-caregiver/family members or hypothetical scenarios’ utilities (n = 16) (Table 2). Fifty (63%) reported caregiver/family member utilities only (Table 3).Footnote 3

Some articles reported utilities for multiple conditions or using multiple measurement methods, or for multiple strata of caregivers/family members. Across all 80 articles, Alzheimer’s disease and other types of dementia were the most frequent focus (15 articles), followed by cancer (6 articles) (Tables 1, 2, 3). Over half of the studies focused on caregivers/family members of ill adults (47, or 59%), 14 on ill children (18%), and the remainder focused on adults and children combined. The EQ-5D was the most common instrument used to measure caregiver/family member utility (58, or 69%, of uses among 84 in total; some articles reported multiple measurement methods). Indeed, 95% of articles used generic (i.e., indirect) measurement instruments: the SF-6D was used in 13 instances (16%), and the HUI and QWB were used three and two times, respectively. The caregiver-focused instruments (the CarerQol and CES) were used in seven instances (six uses and one use, respectively; 9%). Six articles (8%) reported caregiver/family member utility in the context of a patient and/or caregiver intervention trial. Most spillover effects research has been conducted in Europe (53 articles, 66%), followed by the US and Canada (20 articles, 25%). The earliest article reporting on this topic was published in 1988; nearly half (49%) were published between 2015 and 2018 (Tables 1, 2, 3).

4 Discussion

The past two decades have seen research on spillover health effects progress from a conceptual framework [15] to methods for measurement and incorporation into CEAs [14, 16, 27, 31, 32]. In 2016, the Second Panel on Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine endorsed the inclusion of caregiver and family member effects in societal perspective CEAs, while at the same time acknowledging current limitations in measurement methodology and practice [9]. Dutch and National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines also recommend inclusion of spillover effects [10, 11]. This systematic review facilitates adherence to current recommendations by providing a catalog of preference-based values for spillover effects available to date. It is broader and more comprehensive than a previous review that focused on spillover utility only; this review includes caregiver and family member utilities from which spillover can be estimated or derived, and preference-based measures of caregiving effects beyond health [13]. Spillover costs for informal care are also recommended for inclusion, and have been reviewed and discussed elsewhere [17, 18].

Along with this catalog and the opportunity to incorporate spillover effects into CEAs come a host of questions, all of which have practical and policy implications: what is and is not considered spillover by different investigators; how can and cannot spillover be captured using different measures and populations; and how and under what circumstances it should or should not be included in CEAs.

4.1 What is Spillover and How can it be Measured?

‘Spillover’ results from caregiving, simply caring about others, or a combination of the two. What constitutes caregiving for one person may be ordinary behavior for another—the distinction, for example, between ‘regular’ parenting and caregiving for sick children [33]. Caregiving is often shared among family members, it sometimes vacillates between family and paid caregivers (such as when patients cycle between home and hospital), and it changes in nature and intensity over time [34]. Caregiving can provide sustenance to family members who might otherwise feel a lack of control or disengaged from an ill relative, moderating the otherwise burden of care [5]. While the literature tends to focus on primary caregivers, other family members both provide care and experience spillover effects of illness [5, 35]. The inconsistent description of caregiving and family involvement in the literature injects variability into both the estimation of spillover QALYs and how to interpret the policy implications of family-based CEAs.

Health utility scores can capture the health-related spillover effects of caregivers and family members if the health-specific spillover effects are isolated; meaning, the utility associated with solely the caring for or caring about component of having an ill relative. These utility scores can be used to calculate QALYs for CEAs. Care-related measures, such as the CarerQOL, albeit preference-based, include non-health domains in addition to health, and as such are incompatible with CEAs. However, utility scores that reflect only the change in health-related quality of life (HRQOL) associated with spillover are available for just a small set of conditions, therefore other measures of caregiver/family member effects may yield values suitable for use in CEAs when certain assumptions hold.

Most articles in this review fall into the category of conventionally-defined health utility scores: the utility of a caregiver or non-caregiving family member of an ill relative. These scores may include the impact of spillover but also the underlying health of the individual. Elderly caregivers, for example, are likely to have chronic health conditions simultaneous with their caregiving responsibilities, therefore their utility scores will reflect a combination of both effects. In some of these articles, utilities are reported for a matched sample, such as non-caregivers or family members of healthy individuals, or from general population norms, allowing for the calculation of a ‘spillover utility’. In the majority of articles reviewed, however, a comparison group utility is not reported, but an analysis could use an appropriate population norm to derive a spillover utility, carefully considered to match the demographics of the caregiver sample. The underlying assumption in this literature is that spillover effects are additive, yet this has not been empirically demonstrated; interaction effects have been hypothesized [30]. While a growing supply of spillover utility data is available in the literature, much of it requires assumptions such as this to be able to use these utilities in a CEA. A further challenge is that the current literature rarely distinguishes between caring for and caring about effects, which may be difficult to disentangle.

Caregiver-focused ‘utility equivalents’ are preference-based but are distinct from QALYs. These measures—the CarerQol and CES—include a different and more comprehensive set of dimensions than are typically included in QALY-based measures (e.g., fulfillment, financial problems, relational problems). While they may accurately capture caregiver-relevant dimensions [36], their valuations are based on a care-related quality-of-life scale so cannot be used to estimate QALYs, and therefore can neither be combined with patient QALYs in CEAs nor compared with CEAs based on QALYs [20]. They are of particular value, however, for comparatively evaluating caregiver interventions. An early prototype of a caregiver-specific measure that was QALY-based but focused on caregiver-relevant dimensions—the Caregiver Quality of Life Index (CGLI)—was largely supplanted by these instruments [37].

4.2 How and Under What Circumstances Should Spillover be Included in Cost-Effectiveness Analyses?

Incorporation of spillover effects into CEAs faces significant methodological questions, including concerns regarding prioritizing caregiver health over patient health, equity in decision making, and ‘double counting’ of benefits. At the most basic level, spillover and patient QALYs can be summed to arrive at total QALYs, and this is currently the most common approach observed in practice. Some have proposed a weighting factor be applied to adjust for the relative importance of spillover effects compared with changes in health for the primary patient [14]. In the extreme, including spillover QALYs could tilt decisions toward benefiting caregivers/family members over the patient, although this is not the intended purpose of considering these effects [38]. Whose QALYs to include in spillover is also an unanswered question as evidence suggests effects extend beyond the primary caregiver [39] and perceptions of relevance (i.e. ‘closeness’) vary across individuals [40]. The articles in this review provide the data to inform family-based CEAs but do not inform the questions underlying appropriate incorporation approaches.

Equity issues are significant in including spillover effects in CEAs. If spillover is included, cost-effectiveness ratios for interventions targeting diseases/conditions that require caretaking and/or negatively affect family members could be favored over diseases/conditions that do not. Interventions that affect oftentimes isolated patients, such as homeless individuals, could be undervalued relative to those that affect more connected individuals, such as children. At the same time, not including spillover could result in policy decisions that disregard the interests of caregivers and families [38, 41]. While it might be sensible to consider the effect of pediatric conditions on parents as well as the child, as successful treatment confers benefits on both, in cases such as dementia, patients’ and families’ interests may at times be at odds: successful treatment may prolong the patient’s life and extend the caretaking burden for the family. Including spillover QALYs in CEAs is both a methodological decision, including the ‘what’ and ‘how’ aspects, and a normative decision, including the ‘if’ and ‘when’ aspects. Whether it is normatively justifiable to include spillover in economic evaluation recognizing the potential reallocation of resources that may ensue is as yet unresolved [38, 41]. It is clear, however, that including spillover necessitates the accurate and normative definition of ‘who qualifies’, as who is or is not included can have an impact on the results, regardless of how those results are used in policy.

Another concern raised with regard to including spillover in CEAs is double counting: spillover effects may already be implicitly included in utilities. Patients’ anxiety or depression, for example, may be a function of their condition’s effect on their family, rather than or in addition to its effect on themselves, indicating that family spillover may be at least in part reflected in patient utilities. Moreover, it may be difficult for caregivers or family members to disentangle their health from their ill relative’s, therefore their ‘spillover’ utility may include more than the effect on themselves individually. Although reasonable concerns, difficulty in measurement ought not preclude the incorporation of an endorsed component of effects. Advances in measurements, most of which use direct utility elicitation methods, have been made to attempt to accurately capture spillover independently, although with unconfirmed success [27, 28, 30]. Judicious use of sensitivity analysis may be a reasonable approach for the time being to minimize the effect of potential measurement error on CEA results.

4.3 Study Limitations

Considerations should be noted regarding our review. While our search is comprehensive as of our end date, articles including utilities for spillover effects are being published with increasing frequency [19], and will soon render our catalog incomplete. We are in the process of developing an online, open-access repository of spillover effect utilities, which will be updated regularly as a public resource. Moreover, our catalog excludes the gray literature or unpublished sources. Unpublished utilities that are in the pipeline, via conference presentations and abstracts, will likely find their way into the published literature in the future and will be incorporated into successive versions of the catalog. Publication bias is not a concern for this review because our results are descriptive and not intended for inference. We limited the data included in our tables to ensure accessibility for readers—essentially a size that was viewable on a standard size page or computer screen—therefore details that are important to some may have been omitted. Finally, we made subjective judgments about the relative salience of utilities in articles reporting multiples, but describe others in the ‘notes’ section of the tables.

5 Conclusions

The scope of CEAs is expanding from patient-based analyses to caregiver/patient dyadic and family-based analyses. While this expansion is consistent with theoretical principles of maximizing health benefits, prevailing methodological consensus, and demographic and health system changes, it raises practical challenges for CEA and highlights data gaps. It is likely, at least for the time being, that QALYs are here to stay [42]. Caregiver and family member spillover effects will therefore be primarily measured in QALYs and will consequently require utilities. This review provides a catalog of utilities to facilitate the calculation of QALYs and inform CEAs. Additional research is needed on methods of measuring and incorporating spillover QALYs to promote, among other things, an accurate reflection of societal preferences for caregiver/family effects relative to patients’ effects. It is our goal to advance the inclusion of spillover in CEA by providing this accessible overview of the spillover effects of HRQOL literature. We also aspire to expand the knowledge base of spillover-based CEAs, from which we will answer these remaining questions.

Data Availability

All data used in this study are publicly available in the form of published journal articles. The summary data included in the tables are extracted directly from the articles. All data are therefore reported directly in the paper or available to the public.

Notes

We use ‘CEA’ to include cost-utility analysis for ease of reading.

Disutility is the utility loss associated with a particular state of health, as opposed to the utility of that state of health.

Multiple studies reported utilities for more than one disease/condition, each of which is represented in the tables as a separate entry.

References

Wittenberg E, Prosser LA. Health as a family affair. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(19):1804–6.

Christakis NA, Allison PD. Mortality after the hospitalization of a spouse. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(7):719–30.

Richardson TJ, Lee SJ, Berg-Weger M, Grossberg GT. Caregiver health: health of caregivers of Alzheimer’s and other dementia patients. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2013;15(7):367.

Tilford JM, Grosse SD, Robbins JM, Pyne JM, Cleves MA, Hobbs CA. Health state preference scores of children with spina bifida and their caregivers. Qual Life Res. 2005;14(4):1087–98.

Wittenberg E, Saada A, Prosser LA. How illness affects family members: a qualitative interview survey. Patient. 2013;6(4):257–68.

Roth DL, Fredman L, Haley WE. Informal caregiving and its impact on health: a reappraisal from population-based studies. Gerontologist. 2015;55(2):309–19.

Brouwer WBF, van Exel NJA, van den Berg B, van den Bos GAM, Koopmanschap MA. Process utility from providing informal care: the benefit of caring. Health Policy. 2005;74(1):85–99.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Methods for the development of NICE public health guidance. 3rd ed. 2012. https://www.nice.org.uk/process/pmg4/chapter/incorporating-health-economics. Accessed 18 Aug 2017.

Sanders GD, Neumann PJ, Basu A, Brock DW, Feeny D, Krahn M, et al. Recommendations for conduct, methodological practices, and reporting of cost-effectiveness analyses: second panel on cost-effectiveness in health and medicine. JAMA. 2016;316(10):1093–103.

Versteegh M, Knies S, Brouwer W. From good to better: new Dutch guidelines for economic evaluations in healthcare. Pharmacoeconomics. 2016;34(11):1071–4.

Cowles E, Marsden G, Cole A, Devlin N. A review of NICE methods and processes across health technology assessment programmes: why the differences and what is the impact? Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2017;15(4):469–77.

Al-Janabi H, Flynn TN, Coast J. QALYs and carers. Pharmacoeconomics. 2011;29(12):1015–23.

Wittenberg E, Prosser LA. Disutility of illness for caregivers and families: a systematic review of the literature. Pharmacoeconomics. 2013;31(6):489–500.

Al-Janabi H, van Exel J, Brouwer W, Coast J. A framework for including family health spillovers in economic evaluation. Med Decis Making. 2016;36(2):176–86.

Basu A, Meltzer D. Implications of spillover effects within the family for medical cost-effectiveness analysis. J Health Econ. 2005;24(4):751–73.

Hoefman RJ, van Exel J, Brouwer W. How to include informal care in economic evaluations. Pharmacoeconomics. 2013;31(12):1105–19.

Krol M, Papenburg J, van Exel J. Does including informal care in economic evaluations matter? A systematic review of inclusion and impact of informal care in cost-effectiveness studies. Pharmacoeconomics. 2015;33(2):123–35.

Grosse S, Jamison P, Soelaeman R, Tilford JM. Quantifying family spillover effects in economic evaluations: measurement and valuation of informal care time. Pharmacoeconomics. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-019-00782-9.

Lin P-J, D’Cruz B, Leech A, Neumann P, Aigbogun M, Oberdhan D, et al. Family and caregiver spillover effects in cost-effectiveness analyses of Alzheimer’s disease interventions. Pharmacoeconomics. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-019-00788-3.

Hoefman RJ, van Exel J, Brouwer WB. Measuring care-related quality of life of caregivers for use in economic evaluations: CarerQol tariffs for Australia, Germany, Sweden, UK, and US. Pharmacoeconomics. 2017;35(4):469–78.

Al-Janabi H, Flynn TN, Coast J. Estimation of a preference-based carer experience scale. Med Decis Making. 2011;31(3):458–68.

Hunink M, Weinstein M, Wittenberg E. Decision making in health and medicine integrating evidence and values. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2014.

Landfeldt E, Lindgren P, Bell CF, Guglieri M, Straub V, Lochmuller H, et al. Quantifying the burden of caregiving in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Neurol. 2016;263(5):906–15.

Poley MJ, Brouwer WB, van Exel NJ, Tibboel D. Assessing health-related quality-of-life changes in informal caregivers: an evaluation in parents of children with major congenital anomalies. Qual Life Res. 2012;21(5):849–61.

Brouwer WBF, van Exel NJA, van de Berg B, Dinant HJ, Koopmanschap MA, van den Bos GAM. Burden of caregiving: evidence of objective burden, subjective burden, and quality of life impacts on informal caregivers of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2004;51(4):570–7.

Crawford B, Hashim SSM, Prepageran N, See GB, Meier G, Wada K, et al. Impact of pediatric acute otitis media on child and parental quality of life and associated productivity loss in Malaysia: a prospective observational study. Drugs Real World Outcomes. 2017;4(1):21–31.

Prosser LA, Lamarand K, Gebremariam A, Wittenberg E. Measuring family HRQoL spillover effects using direct health utility assessment. Med Decis Making. 2015;35(1):81–93.

Davidson T, Krevars B, Levin LA. In pursuit of QALY weights for relatives: empirical estimates in relatives caring for older people. Eur J Health Econ. 2008;9(3):285–92.

Wittenberg E, Bray JW, Aden B, Gebremariam A, Nosyk B, Schackman BR. Measuring benefits of opioid misuse treatment for economic evaluation: health-related quality of life of opioid-dependent individuals and their spouses as assessed by a sample of the US population. Addiction. 2016;111(4):675–84.

Basu A, Dale W, Elstein A, Meltzer D. A time tradeoff method for eliciting partner’s quality of life due to patient’s health states in prostate cancer. Med Decis Making. 2010;30(3):355–65.

Tilford JM, Payakachat N. Progress in measuring family spillover effects for economic evaluations. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2015;15(2):195–8.

Brown Tilford JM. Measuring caregiver spillover effects associated with autism spectrum disorder: a comparison of the EQ-5D-3L and SF-6D. Pharmacoeconomics. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-019-00789-2.

Ungar WE. Economic evaluation in child health. New York: Oxford University Press; 2010.

Caregiving in the US 2015. Bethesda: National Alliance for Caregiving (NAC) and the AARP Public Policy Institute; 2015.

Bobinac A, van Exel NJA, Rutten FFH, Brouwer WBF. Caring for and caring about: disentangling the caregiver effect and the family effect. J Health Econ. 2010;29(4):549–56.

Hoefman RJ, van Exel J, Brouwer WB. Measuring the impact of caregiving on informal carers: a construct validation study of the CarerQol instrument. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013;11:173.

Mohide EA, Torrance GW, Streiner DL, Pringle DM, Gilbert R. Measuring the wellbeing of family caregivers using the time trade-off technique. J Clin Epidemiol. 1988;41(5):475–82.

McCabe C. Spillover effects and economic evaluations in health: some words of caution. Pharmacoeconomics. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-018-0729-z.

Bhadhuri A, Jowett S, Jolly K, Al-Janabi H. A comparison of the validity and responsiveness of the EQ-5D-5L and SF-6D for measuring health spillovers: a study of the family impact of Meningitis. Med Decis Making. 2017;37(8):882–93.

Canaway A, Al-Janabi H, Kinghorn P, Coast J. Close-person spill-overs in end-of-life care: using hierarchical mapping to identify whose outcomes to include in economic evaluation. Phamacoeconomics. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-019-00786-5.

Brouwer W. The inclusion of spill-over effects in economic evaluations: not an optional extra. Pharmacoeconomics. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-018-0730-6.

Neumann PJ, Cohen JT. QALYs in 2018—advantages and concerns. JAMA. 2018;319(24):2473–4.

Landfeldt E, Lindgren P, Bell CF, Guglieri M, Straub V, Lochmuller H, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy: a multinational, cross-sectional study. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2016;58(5):508–15.

Kuhlthau K, Kahn R, Hill KS, Gnanasekaran S, Ettner SL. The well-being of parental caregivers of children with activity limitations. Matern Child Health J. 2010;14(2):155–63.

Thomas GPA, Saunders CL, Roland MO, Paddison CAM. Informal carers’ health-related quality of life and patient experience in primary care: evidence from 195,364 carers in England responding to a national survey. BMC Fam Pract. 2015;16:62.

Song JI, Shin DW, Choi J-Y, Kang J, Baek Y-J, Mo H-N, et al. Quality of life and mental health in the bereaved family members of patients with terminal cancer. Psychooncology. 2012;21(11):1158–66.

Lee HJ, Park E-C, Kim SJ, Lee SG. Quality of life of family members living with cancer patients. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16(16):6913–7.

Zhou H, Zhang L, Ye F, Wang H-J, Huntington D, Huang Y, et al. The effect of maternal death on the health of the husband and children in a rural area of China: a prospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2016;11(6):e0157122.

Gupta S, Goren A, Phillips AL, Stewart M. Self-reported burden among caregivers of patients with multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2012;14(4):179–87.

Laks J, Goren A, Duenas H, Novick D, Kahle-Wrobleski K. Caregiving for patients with Alzheimer’s disease or dementia and its association with psychiatric and clinical comorbidities and other health outcomes in Brazil. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016;31(2):176–85.

Rochanathimoke O, Riewpaiboon A, Postma MJ, Thinyounyong W, Thavorncharoensap M. Health related quality of life impact from rotavirus diarrhea on children and their family caregivers in Thailand. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2018;18(2):215–22.

Brisson M, Senecal M, Drolet M, Mansi JA. Health-related quality of life lost to rotavirus-associated gastroenteritis in children and their parents: a Canadian prospective study. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2010;29(1):73–5.

Al-Janabi H, Van Exel J, Brouwer W, Trotter C, Glennie L, Hannigan L, et al. Measuring health spillovers for economic evaluation: a case study in meningitis. Health Econ. 2016;25(12):1529–44.

Acaster S, Perard R, Chauhan D, Lloyd AJ. A forgotten aspect of the NICE reference case: an observational study of the health related quality of life impact on caregivers of people with multiple sclerosis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:346.

Gupta S, Isherwood G, Jones K, Van Impe K. Assessing health status in informal schizophrenia caregivers compared with health status in non-caregivers and caregivers of other conditions. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15:162.

Persson J, Levin L-A, Holmegaard L, Redfors P, Jood K, Jern C, et al. Stroke survivors’ long-term QALY-weights in relation to their spouses’ QALY-weights and informal support: a cross-sectional study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2017;15(1):150.

Persson J, Aronsson M, Holmegaard L, Redfors P, Stenlof K, Jood K, et al. Long-term QALY-weights among spouses of dependent and independent midlife stroke survivors. Qual Life Res. 2017;26(11):3059–68.

Nogueira JM, Rodriguez-Miguez E. Using the SF-6D to measure the impact of alcohol dependence on health-related quality of life. Eur J Health Econ. 2015;16(4):347–56.

Sjolander C, Rolander B, Järhult J, Mårtensson J, Ahlstrom G. Health-related quality of life in family members of patients with an advanced cancer diagnosis: a one-year prospective study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2012;10:89.

Angelis A, Kanavos P, Lopez-Bastida J, Linertova R, Nicod E, Serrano-Aguilar P, et al. Social and economic costs and health-related quality of life in non-institutionalised patients with cystic fibrosis in the United Kingdom. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:428.

van Andel J, Westerhuis W, Zijlmans M, Fischer K, Leijten FSS. Coping style and health-related quality of life in caregivers of epilepsy patients. J Neurol. 2011;258(10):1788–94.

Kurien M, Andrews RE, Tattersall R, McAlindon ME, Wong EF, Johnston AJ, et al. Gastrostomies preserve but do not increase quality of life for patients and caregivers. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15(7):1047–54.

van Exel NJ, Koopmanschap MA, van den Berg B, Brouwer WB, van den Bos GA. Burden of informal caregiving for stroke patients. Identification of caregivers at risk of adverse health effects. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2005;19(1):11–7.

Brouwer WBF, van Exel NJA, van Gorp B, Redekop WK. The CarerQol instrument: a new instrument to measure care-related quality of life of informal caregivers for use in economic evaluations. Qual Life Res. 2006;15(6):1005–21.

Lutomski JE, van Exel NJA, Kempen GIJM, Moll van Charante EP, den Elzen WPJ, Jansen APD, et al. Validation of the Care-Related Quality of Life Instrument in different study settings: findings from The Older Persons and Informal Caregivers Survey Minimum DataSet (TOPICS-MDS). Qual Life Res. 2015;24(5):1281–93.

del Rio Lozano M, Garcia-Calvente MDM, Calle-Romero J, Machon-Sobrado M, Larranaga-Padilla I. Health-related quality of life in Spanish informal caregivers: gender differences and support received. Qual Life Res. 2017;26(12):3227–38.

Oldenkamp M, Hagedoorn M, Wittek R, Stolk R, Smidt N. The impact of older person’s frailty on the care-related quality of life of their informal caregiver over time: results from the TOPICS-MDS project. Qual Life Res. 2017;26(10):2705–16.

Hoefman R, Payakachat N, van Exel J, Kuhlthau K, Kovacs E, Pyne J, et al. Caring for a child with autism spectrum disorder and parents’ quality of life: application of the CarerQol. J Autism Dev Disord. 2014;44(8):1933–45.

Khanna R, Jariwala K, Bentley JP. Psychometric properties of the EuroQol Five Dimensional Questionnaire (EQ-5D-3L) in caregivers of autistic children. Qual Life Res. 2013;22(10):2909–20.

Khanna R, Jariwala K, Bentley JP. Health utility assessment using EQ-5D among caregivers of children with autism. Value Health. 2013;16(5):778–88.

Vrettos I, Kamposioras K, Kontodimopoulos N, Pappa E, Georgiadou E, Haritos D, et al. Comparing health-related quality of life of cancer patients under chemotherapy and of their caregivers. ScientificWorldJournal. 2012;2012:135283.

Bradshaw LE, Goldberg SE, Schneider JM, Harwood RH. Carers for older people with co-morbid cognitive impairment in general hospital: characteristics and psychological well-being. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;28(7):681–90.

Payakachat N, Tilford JM, Brouwer WB, van Exel NJ, Grosse SD. Measuring health and well-being effects in family caregivers of children with craniofacial malformations. Qual Life Res. 2011;20(9):1487–95.

Chevreul K. Social/economic costs and health-related quality of life in patients with cystic fibrosis in Europe. Eur J Health Econ. 2016;17:s7–18.

Chevreul K, Berg Brigham K, Michel M, Rault G. Costs and health-related quality of life of patients with cystic fibrosis and their carers in France. J Cyst Fibros. 2015;14(3):384–91.

Fitzgerald C, George S, Somerville R, Linnane B, Fitzpatrick P. Caregiver burden of parents of young children with cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2018;17(1):125–31.

Kraijo H, Brouwer W, de Leeuw R, Schrijvers G, van Exel J. The perseverance time of informal carers of dementia patients: validation of a new measure to initiate transition of care at home to nursing home care. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;40(3):631–42.

Bell CM, Araki SS, Neumann PJ. The association between caregiver burden and caregiver health-related quality of life in Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2001;15(3):129–36.

Fang M, Oremus M, Tarride J-E, Raina P, Canadian Willingness-to-pay Study Group. A comparison of health utility scores calculated using United Kingdom and Canadian preference weights in persons with Alzheimer’s disease and their caregivers. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2016;14(1):105.

Majoni M, Oremus M. Does being a retired or employed caregiver affect the association between behaviours in Alzheimer’s disease and caregivers’ health-related quality-of-life? BMC Res Notes. 2017;10(1):766.

Neumann PJ, Sandberg EA, Araki SS, Kuntz KM, Feeny D, Weinstein MC. A comparison of HUI2 and HUI3 utility scores in Alzheimer’s disease. Med Decis Making. 2000;20(4):413–22.

Oremus M, Tarride J-E, Clayton N, Canadian Willingness-to-Pay Study Group, Raina P. Health utility scores in Alzheimer’s disease: differences based on calculation with American and Canadian preference weights. Value Health. 2014;17(1):77–83.

Reed C, Barrett A, Lebrec J, Dodel R, Jones RW, Vellas B, et al. How useful is the EQ-5D in assessing the impact of caring for people with Alzheimer’s disease? Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2017;15(1):16.

Dahlrup B, Nordell E, Steen Carlsson K, Elmstahl S. Health economic analysis on a psychosocial intervention for family caregivers of persons with dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2014;37(3–4):181–95.

Knapp M, King D, Romeo R, Schehl B, Barber J, Griffin M, et al. Cost effectiveness of a manual based coping strategy programme in promoting the mental health of family carers of people with dementia (the START (STrAtegies for RelaTives) study): a pragmatic randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2013;347:f6342.

Orrell M, Yates L, Leung P, Kang S, Hoare Z, Whitaker C, et al. The impact of individual Cognitive Stimulation Therapy (iCST) on cognition, quality of life, caregiver health, and family relationships in dementia: a randomised controlled trial. PLoS Med. 2017;14(3):e1002269.

Stewart S, Harvey I, Poland F, Lloyd-Smith W, Mugford M, Flood C. Are occupational therapists more effective than social workers when assessing frail older people? Results of CAMELOT, a randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing. 2005;34(1):41–6.

Vroomen JM, Bosmans JE, Eekhout I, Joling KJ, Van Mierlo LD, Meiland FJM, et al. The cost-effectiveness of two forms of case management compared to a control group for persons with dementia and their informal caregivers from a societal perspective. PLoS One. 2016;11(9):e0160908.

Tiberg I, Lindgren B, Carlsson A, Hallstrom I. Cost-effectiveness and cost-utility analyses of hospital-based home care compared to hospital-based care for children diagnosed with type 1 diabetes; a randomised controlled trial; results after two years’ follow-up. BMC Pediatr. 2016;16:94.

Campbell JD, Whittington MD, Kim CH, VanderVeen GR, Knupp KG, Gammaitoni A. Assessing the impact of caring for a child with Dravet syndrome: results of a caregiver survey. Epilepsy Behav. 2018;80:152–6.

Cavazza M, Kodra Y, Armeni P, De Santis M, López-Bastida J, Linertová R, et al. Social/economic costs and health-related quality of life in patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy in Europe. Eur J Health Econ. 2016;17:19–29.

Chevreul K, Gandré C, Brigham KB, López-Bastida J, Linertová R, Oliva-Moreno J, et al. Social/economic costs and health-related quality of life in patients with fragile X syndrome in Europe. Eur J Health Econ. 2016;17:43–52.

Chevreul K, Berg Brigham K, Brunn M, des Portes V, Network B-RR. Fragile X syndrome: economic burden and health-related quality of life of patients and caregivers in France. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2015;59(12):1108–20.

Agren S, Evangelista L, Davidson T, Stromberg A. Cost-effectiveness of a nurse-led education and psychosocial programme for patients with chronic heart failure and their partners. J Clin Nurs. 2013;22(15–16):2347–53.

Iqbal J, Francis L, Reid J, Murray S, Denvir M. Quality of life in patients with chronic heart failure and their carers: a 3-year follow-up study assessing hospitalization and mortality. Eur J Heart Fail. 2010;12(9):1002–8.

Squire L, Glover J, Corp J, Haroun R, Kuzan D, Gielen V. Impact of HF on HRQoL in patients and their caregivers in England: results from the ASSESS study. Br J Cardiol. 2017;24(1):30–4.

Cavazza M, Kodra Y, Armeni P, De Santis M, López-Bastida J, Linertová R, et al. Social/economic costs and quality of life in patients with haemophilia in Europe. Eur J Health Econ. 2016;17:53–65.

Al-Janabi H, Manca A, Coast J. Predicting carer health effects for use in economic evaluation. PLoS One. 2017;12(9):e0184886.

Hastrup LH, Van Den Berg B, Gyrd-Hansen D. Do informal caregivers in mental illness feel more burdened? A comparative study of mental versus somatic illnesses. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(6):598–607.

Péntek M, Gulácsi L, Brodszky V, Baji P, Boncz I, Pogány G, et al. Social/economic costs and health-related quality of life of mucopolysaccharidosis patients and their caregivers in Europe. Eur J Health Econ. 2016;17:89–98.

Hoefman R, Al-Janabi H, McCaffrey N, Currow D, Ratcliffe J. Measuring caregiver outcomes in palliative care: a construct validation study of two instruments for use in economic evaluations. Qual Life Res. 2015;24(5):1255–73.

Carod-Artal FJ, Mesquita HM, Ziomkowski S, Martinez-Martin P. Burden and health-related quality of life among caregivers of Brazilian Parkinson’s disease patients. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2013;19(11):943–8.

Martinez-Martin P, Forjaz MJ, Frades-Payo B, Rusinol AB, Fernandez-Garcia JM, Benito-Leon J, et al. Caregiver burden in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2007;22(7):924–1060.

Martinez-Martin P, Arroyo S, Rojo-Abuin JM, Rodriguez-Blazquez C, Frades B, de Pedro Cuesta J, et al. Burden, perceived health status, and mood among caregivers of Parkinson’s disease patients. Mov Disord. 2008;23(12):1673–80.

Chevreul K, Berg Brigham K, Clément MC, Poitou C, Tauber M. Economic burden and health-related quality of life associated with Prader–Willi syndrome in France. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2016;60(9):879–90.

van Dam PH, Achterberg WP, Caljouw MAA. Care-related quality of life of informal caregivers after geriatric rehabilitation. J Am Med Direct Assoc. 2017;18(3):259–64.

Daltio CS, Attux C, Ferraz MB. Willingness to pay in caregivers of patients affected by schizophrenia. J Mental Health Policy Econ. 2017;20(1):3–10.

Cramm JM, Strating MMH, Nieboer AP. Satisfaction with care as a quality-of-life predictor for stroke patients and their caregivers. Qual Life Res. 2012;21(10):1719–25.

Carod-Artal FJ, Ferreira Coral L, Trizotto DS, Menezes Moreira C. Burden and perceived health status among caregivers of stroke patients. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2009;28(5):472–80.

Chevreul K, Brigham KB, Gandré C, Mouthon L, Serrano-Aguilar P, Linertová R, et al. The economic burden and health-related quality of life associated with systemic sclerosis in France. Scand J Rheumatol. 2015;44(3):238–46.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the invaluable assistance of Paul Bain, PhD, Research and Education Librarian, Countway Library of Medicine, in developing and implementing the literature search strategy, and Angela Rose, University of Michigan Medical School, for research assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EW and LAP conceptualized the study; EW and LPJ developed the search strategy and reviewed articles; LPJ conducted the search and developed tables/figures of the results; EW wrote the first draft of the manuscript; EW, LPJ, and LAP provided feedback and edited interim drafts; EW completed the final draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

No funding was received for the conduct of this study.

Conflict of interest

Eve Wittenberg, Lyndon James, and Lisa Prosser have no conflicts of interest to report.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Wittenberg, E., James, L.P. & Prosser, L.A. Spillover Effects on Caregivers’ and Family Members’ Utility: A Systematic Review of the Literature. PharmacoEconomics 37, 475–499 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-019-00768-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-019-00768-7