Abstract

Context

This study assesses if, and how, existing methods for economic evaluation are applicable to the evaluation of personalized medicine (PM) and, if not, where extension to methods may be required.

Methods

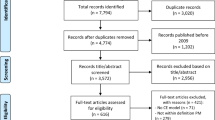

A structured workshop was held with a predefined group of experts (n = 47), and was run using a modified nominal group technique. Workshop findings were recorded using extensive note taking, and summarized using thematic data analysis. The workshop was complemented by structured literature searches.

Results

The key finding emerging from the workshop, using an economic perspective, was that two distinct, but linked, interpretations of the concept of PM exist (personalization by ‘physiology’ or ‘preferences’). These interpretations involve specific challenges for the design and conduct of economic evaluations. Existing evaluative (extra-welfarist) frameworks were generally considered appropriate for evaluating PM. When ‘personalization’ is viewed as using physiological biomarkers, challenges include representing complex care pathways; representing spillover effects; meeting data requirements such as evidence on heterogeneity; and choosing appropriate time horizons for the value of further research in uncertainty analysis. When viewed as tailoring medicine to patient preferences, further work is needed regarding revealed preferences, e.g. treatment (non)adherence; stated preferences, e.g. risk interpretation and attitude; consideration of heterogeneity in preferences; and the appropriate framework (welfarism vs. extra-welfarism) to incorporate non-health benefits.

Conclusions

Ideally, economic evaluations should take account of both interpretations of PM and consider physiology and preferences. It is important for decision makers to be cognizant of the issues involved with the economic evaluation of PM to appropriately interpret the evidence and target future research funding.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Schleidgen S, Klingler C, Bertram T, Rogowski WH, Marckmann G. What is personalized medicine: sharpening a vague term based on a systematic literature review. BMC Med Ethics. 2013;14:55.

Faulkner E, Annemans L, Garrison L, Helfand M, Holtorf AP, Hornberger J, et al. Challenges in the development and reimbursement of personalized medicine-payer and manufacturer perspectives and implications for health economics and outcomes research: a report of the ISPOR personalized medicine special interest group. Value Health. 2012;15(8):1162–71.

Berger AC, Olson S. The economics of genomic medicine: workshop summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies; 2013.

Rogowski WH, Grosse SD, Khoury MJ. Challenges of translating genetic tests into clinical and public health practice. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10(7):489–95.

Annemans L, Redekop K, Payne K. Current methodological issues in the economic assessment of personalized medicine. Value Health. 2013;16(6 Suppl):S20–6.

Bloss G, Haaga JG. Economics of personalized health care and prevention: introduction. Forum Health Econ Policy. 2013;16(2):35–45.

Sorich MJ, Wiese MD, O’Shea RL, Pekarsky B. Review of the cost effectiveness of pharmacogenetic-guided treatment of hypercholesterolaemia. Pharmacoeconomics. 2013;31(5):377–91.

Vegter S, Boersma C, Rozenbaum M, Wilffert B, Navis G, Postma MJ. Pharmacoeconomic evaluations of pharmacogenetic and genomic screening programmes: a systematic review on content and adherence to guidelines. Pharmacoeconomics. 2008;26(7):569–87.

Payne K, Newman WG, Gurwitz D, Ibarreta D, Phillips KA. TPMT testing in azathioprine: a ‘cost-effective use of healthcare resources’? Personal Med. 2009;6(1):103–13.

Wong WB, Carlson JJ, Thariani R, Veenstra DL. Cost effectiveness of pharmacogenomics: a critical and systematic review. Pharmacoeconomics. 2010;28(11):1001–13.

Phillips KA, Ann Sakowski J, Trosman J, Douglas MP, Liang SY, Neumann P. The economic value of personalized medicine tests: what we know and what we need to know. Genet Med. 2014;16(3):251–7.

Basu A. Economics of individualization in comparative effectiveness research and a basis for a patient-centered health care. J Health Econ. 2011;30(3):549–59.

Basu A, Meltzer D. Value of information on preference heterogeneity and individualized care. Med Decis Making. 2007;27(2):112–27.

Payne K, Thompson AJ. Economics of pharmacogenomics: rethinking beyond QALYs? Curr Pharmacogenomics Personal Med. In press.

Jones J, Hunter D. Consensus methods for medical and health services research. BMJ. 1995;311(7001):376–80.

Ding A, Eisenberg JD, Pandharipande PV. The economic burden of incidentally detected findings. Radiol Clin North Am. 2011;49(2):257–65.

Carlson JJ, Henrikson NB, Veenstra DL, Ramsey SD. Economic analyses of human genetics services: a systematic review. Genet Med. 2005;7(8):519–23.

Rogowski W. Genetic screening by DNA technology: a systematic review of health economic evidence. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2006;22(3):327–37.

Djalalov S, Musa Z, Mendelson M, Siminovitch K, Hoch J. A review of economic evaluations of genetic testing services and interventions (2004–2009). Genet Med. 2011;13(2):89–94.

Siebert U, Alagoz O, Bayoumi AM, Jahn B, Owens DK, Cohen DJ, et al. State-transition modeling: a report of the ISPOR-SMDM Modeling Good Research Practices Task Force–3. Value Health. 2012;15(6):812–20.

Karnon J, Stahl J, Brennan A, Caro JJ, Mar J, Moller J. Modeling using discrete event simulation: a report of the ISPOR-SMDM Modeling Good Research Practices Task Force–4. Value Health. 2012;15(6):821–7.

Mvundura M, Grosse SD, Hampel H, Palomaki GE. The cost-effectiveness of genetic testing strategies for Lynch syndrome among newly diagnosed patients with colorectal cancer. Genet Med. 2010;15(12):93–104.

Basu A, Jena AB, Goldman DP, Philipson TJ, Dubois R. Heterogeneity in action: the role of passive personalization in comparative effectiveness research. Health Econ. Epub 9 Oct 2013. doi:10.1002/hec.2996

Espinoza M, Manca A, Claxton K, Sculpher M. The value of heterogeneity for cost-effectiveness subgroup analysis: conceptual framework and application. Med Decis Making. Epub 18 Jun 2014.

Paget MA, Chuang-Stein C, Fletcher C, Reid C. Subgroup analyses of clinical effectiveness to support health technology assessments. Pharm Stat. 2011;10:532–8.

Laking G, Lord J, Fischer A. The economics of diagnosis. Health Econ. 2006;15(10):1109–20.

Grigore B, Peters J, Hyde C, Stein K. Methods to elicit probability distributions from experts: a systematic review of reported practice in health technology assessment. Pharmacoeconomics. 2013;31(11):991–1003.

Johnson ML, Crown W, Martin BC, Dormuth CR, Siebert U. Good research practices for comparative effectiveness research: analytic methods to improve causal inference from nonrandomized studies of treatment effects using secondary data sources: the ISPOR Good Research Practices for Retrospective Database Analysis Task Force Report–Part III. Value Health. 2009;12(8):1062–73.

Rogowski W, Burch J, Palmer S, Craigs C, Golder S, Woolacott N. The effect of different treatment durations of clopidogrel in patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes: a systematic review and value of information analysis. Health Technol Assess. 2009;13(31):1–102.

Siebert U, Rochau U, Claxton K. When is enough evidence enough? Using systematic decision analysis and value-of-information analysis to determine the need for further evidence. Z Evid Fortbild Qual Gesundhwes. 2013;107(9–10):575–84.

Rogowski WH, Grosse SD, Meyer E, John J, Palmer S. Using value of information analysis in decision making about applied research. The case of genetic screening for hemochromatosis in Germany. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2012;55(5):700–9.

Philips Z, Claxton K, Palmer S. The half-life of truth: what are appropriate time horizons for research decisions? Med Decis Mak. 2008;28(3):287–99.

Hatz MH, Schremser K, Rogowski WH. Is individualized medicine more cost-effective? A systematic review. Pharmacoeconomics. 2014;32(5):443–55.

Koerber F, Waidelich R, Stollenwerk B, Rogowski W. The cost-utility of open prostatectomy compared with active surveillance in early localised prostate cancer. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):163.

Elliott RA, Shinogle JA, Peele P, Bhosle M, Hughes DA. Understanding medication compliance and persistence from an economics perspective. Value Health. 2008;11(4):600–10.

Issa AM. Personalized medicine and the practice of medicine in the 21st century. Mcgill J Med. 2007;10(1):53–7.

Robins J, Hernan M, Siebert U. Effects of multiple interventions. In: Ezzati M, Lopez AD, Rodgers A, Murray CJL, editors. Comparative quantification of health risks: global and regional burden of disease attributable to selected major risk factors. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004. p. 2191–230.

Bridges JF, Hauber AB, Marshall D, Lloyd A, Prosser LA, Regier DA, et al. Conjoint analysis applications in health–a checklist: a report of the ISPOR Good Research Practices for Conjoint Analysis Task Force. Value Health. 2011;14(4):403–13.

Reed Johnson F, Lancsar E, Marshall D, Kilambi V, Muhlbacher A, Regier DA, et al. Constructing experimental designs for discrete-choice experiments: report of the ISPOR Conjoint Analysis Experimental Design Good Research Practices Task Force. Value Health. 2013;16(1):3–13.

Johnson FR, Hauber AB, Ozdemir S, Lynd L. Quantifying women’s stated benefit-risk trade-off preferences for IBS treatment outcomes. Value Health. 2010;13(4):418–23.

Harrison M, Rigby D, Vass C, Flynn T, Louviere J, Payne K. Risk as an attribute in discrete choice experiments: a systematic review of the literature. Patient. 2014;7(2):151-170.

Ersig AL, Hadley DW, Koehly LM. Colon cancer screening practices and disclosure after receipt of positive or inconclusive genetic test results for hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Cancer. 2009;115(18):4071–9.

Rice T. The behavioral economics of health and health care. Annu Rev Public Health. 2013;34:431–47.

Hole AR. Modelling heterogeneity in patients’ preferences for the attributes of a general practitioner appointment. J Health Econ. 2008;27(4):1078–94.

Fiebig DG, Keane MP, Louviere J, Wasi N. The generalized multinomial logit model: accounting for scale and coefficient heterogeneity. Mark Sci. 2010;29(3):393–421.

Tremmel JC. A theory of intergenerational justice. Düsseldorf: Heinrich-Heine Universität; 2009.

Gough I. Lists and thresholds: comparing the Doyal-Gough theory of human need with Nussbaum’s capabilities approach. In: Comim F, Nussbaum M, editors. Capabilities, gender, equality: towards fundamental entitlements. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2014.

Brouwer WB, Culyer AJ, van Exel NJ, Rutten FF. Welfarism vs. extra-welfarism. J Health Econ. 2008;27(2):325–38.

Rogowski W. Current impact of gene technology on healthcare. A map of economic assessments. Health Policy. 2007;5(80):340–57.

Rogowski WH, Grosse SD, John J, Kääriäinen H, Kent A, Kristofferson U, et al. Points to consider in assessing and appraising predictive genetic tests. J Community Genet. 2010;1(4):185–94.

Grosse SD, Wordsworth S, Payne K. Economic methods for valuing the outcomes of genetic testing: beyond cost-effectiveness analysis. Genet Med. 2008;10(9):648–54.

Neumann PJ, Cohen JT, Hammitt JK, Concannon TW, Auerbach HR, Fang C, et al. Willingness-to-pay for predictive tests with no immediate treatment implications: a survey of US residents. Health Econ. 2012;21(3):238–51.

Smith RD, Sach TH. Contingent valuation: what needs to be done? Health Econ Policy Law. 2010;5(Pt 1):91–111.

Rogowski WH, Hartz SC, John JH. Clearing up the hazy road from bench to bedside: a framework for integrating the fourth hurdle into translational medicine. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8(194):1–12.

Fischer KE, Rogowski WH, Leidl R, Stollenwerk B. Transparency vs. closed-door policy: do process characteristics have an impact on the outcomes of coverage decisions? A statistical analysis. Health Policy. 2013;112(3):187–96.

Culyer A. Need: an instrumental view. In: Ashcroft RE, editor. Principles of health care ethics. Edited by Richard E. Ashcroft, et al. 2nd ed. Chichester: Wiley; 2007. p. 231–8.

Guindo LA, Wagner M, Baltussen R, Rindress D, van Til J, Kind P, et al. From efficacy to equity: Literature review of decision criteria for resource allocation and healthcare decision making. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2012;10(1):9.

Payne K, McAllister M, Davies LM. Valuing the economic benefits of complex interventions: when maximising health is not sufficient. Health Econ. 2013;22(3):258-271.

McAllister M, Dunn G, Payne K, Davies L, Todd C. Patient empowerment: the need to consider it as a measurable patient-reported outcome for chronic conditions. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:157.

Juengst ET, Flatt MA, Settersten Jr RA. Personalized genomic medicine and the rhetoric of empowerment. Hastings Cent Rep. 2012;42(5):34–40.

Sackett DL, Rosenberg WM, Gray JA, Haynes RB, Richardson WS. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t. BMJ. 1996;312(7023):71–2.

Montori VM, Brito JP, Murad MH. The optimal practice of evidence-based medicine: incorporating patient preferences in practice guidelines. JAMA. 2013;310(23):2503–4.

Acknowledgments

The workshop organization and funding, as well as the contribution by Uwe Siebert, Petra Schnell-Inderst, Beate Jahn, and Ursula Rochau, was supported by the COMET Center ONCOTYROL, which is funded by the Austrian Federal Ministries for Transport, Innovation and Technology, and for Economy, Family and Youth (via the Austrian Research Promotion Agency) and the Tiroler Zukunftsstiftung/Standortagentur Tirol (SAT).

We would like to acknowledge the helpful comments from various colleagues and, in particular, insights from members of the International ONCOTYROL Expert Task Force. Special thanks are extended to Elske van den Akker-van Marle for helpful comments during the workshop, and to Sebastian Schleidgen for helpful comments regarding definitions of PM.

The work of Wolf Rogowski in the preparation of this article was supported by the grant ‘Individualized Health Care: Ethical, Economic and Legal Implications for the German Health Care System’ of the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF; grant number 01GP1006B).

The contribution from Andrea Manca was made under the terms of a career development research training fellowship issued by the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR; grant CDF-2009-02-21). Oguzhan Alagoz is funded by grant CMII-0844423 from the National Science Foundation, and grant UL1TR000427 from the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program, through the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS). All other authors have no relevant funding sources to declare.

All of the authors have programmes of work, supported by various public funding bodies, on the economics of PMs and screening programmes which include the research topics addressed here. None of the authors have any direct financial conflicts of interest with regards to this study.

The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the ONCOTYROL Center for Personalized Cancer Medicine, the Helmholtz Center Munich, the UK NHS, the NIHR, or the UK Department of Health.

Author contributions

Wolf Rogowski and Katherine Payne conceived the framework underpinning this study. Wolf Rogowski lead the writing of the manuscript, with large contributions from Katherine Payne. Uwe Siebert initiated and coordinated the ONCOTYROL workshops. Petra Schnell-Inderst, Beate Jahn, and Ursula Rochau conducted literature searches and documented the workshops. Oguzhan Alagoz updated the literature searches. All authors, in particular Andrea Manca and Reiner Leidl, provided substantial intellectual input. All authors were involved in writing of the manuscript, and read and approved the final version. All authors act as guarantors individually.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rogowski, W., Payne, K., Schnell-Inderst, P. et al. Concepts of ‘Personalization’ in Personalized Medicine: Implications for Economic Evaluation. PharmacoEconomics 33, 49–59 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-014-0211-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-014-0211-5