Abstract

External validity is a crucial but under-researched topic when considering using discrete choice experiment (DCE) results to inform decision making in clinical, commercial or policy contexts. We present the theory and tests traditionally used to explore external validity that focus on a comparison of final outcomes and review how this traditional definition has been empirically tested in health economics and other sectors (such as transport, environment and marketing) in which DCE methods are applied. While an important component, we argue that the investigation of external validity should be much broader than a comparison of final outcomes. In doing so, we introduce a new and more comprehensive conceptualisation of external validity, closely linked to process validity, that moves us from the simple characterisation of a model as being or not being externally valid on the basis of predictive performance, to the concept that external validity should be an objective pursued from the initial conceptualisation and design of any DCE. We discuss how such a broader definition of external validity can be fruitfully used and suggest innovative ways in which it can be explored in practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Viney et al. [23] provide another useful example of testing and accounting for scale differences when combining two or more stated preference data sets.

A somewhat more sophisticated approach might also attribute some of the motivation for this decomposition to DM uncertainty about his or her evaluations, but this is beyond the basic RU paradigm.

By process validity we mean that the decision process described by a mathematical and/or statistical model is plausible/valid at the desired level of representation because it bears a semblance to the actual decision process(es). For example, if DMs are actually using threshold-based satisficing as their decision rule, while the mathematical representation of the process employs instead utility maximisation, then we would understand that the process validity of the model is lower than if it were to represent the actual decision rule. This differs from internal validity, which refers to a DM’s consistency with the behavioural axioms (e.g. non-satiation, transitivity, Sen’s expansion/contraction properties) underpinning the random utility maximisation framework.

References

Louviere J, Lancsar E. Discrete choice experiments in health: the good, the bad, the ugly and toward a brighter future. Health Econ Policy Law. 2009;4:527–46.

Ben-Akiva M, Lerman SR. Discrete choice analysis: theory and applications to travel demand. Cambridge: The MIT Press Series in Transportation Studies; 1985.

Louviere JJ, Hensher DA, Swait JD. Stated choice methods: analysis and applications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2000.

Swait J, Louviere JJ. The role of the scale parameter in the estimation of and comparison of multinomial logit models. J Mark Res. 1993;30:305–14.

Swait J, Ben-Akiva M. Empirical test of a constrained choice discrete model: mode choice in São Paulo, Brazil. Transp Res Part B Methodol. 1987;21(2):103–15. doi:10.1016/0191-2615(87)90010.

Habib K, Swait J, Salem S. Using repeated cross sectional travel surveys to enhance forecasting robustness: accounting for changing mode preferences. Toronto: University of Toronto; 2013.

Brownstone D, Small KA. Valuing time and reliability: assessing the evidence from road pricing demonstrations. Transp Res Part A Policy Pract. 2005;39(4):279–93. doi:10.1016/j.tra.2004.11.001.

Fifer S, Rose J, Greaves S. Hypothetical bias in stated choice expeirments: Is it a problem? And if so, how do we deal with it?. Sydney: University of Sydney; 2012.

Cameron TA, Poe GL, Ethier RG, Schulze WD. Alternative non-market value-elicitation methods: are the underlying preferences the same? J Environ Econ Manag. 2002;44(3):391–425. doi:10.1006/jeem.2001.1210.

Adamowicz W, et al. Perceptions versus objective measures of environmental quality in combined revealed and stated preference models of environmental valuation. J Environ Econ Manag. 1997;32(1):65–84.

Carlsson F, Martinsson P. Do hypothetical and actual marginal willingness to pay differ in choice experiments? Application to the valuation of the environment. J Environ Econ Manag. 2001;41(2):179–92. doi:10.1006/jeem.2000.1138.

Bateman I, Carson R, Day B, Hanemann M, Hanley N, Hett T, et al. Economic valuation with stated preference techniques: a manual. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar; 2002.

Vossler CA, Watson SB. Understanding the consequences of consequentiality: Testing the validity of stated preferences in the field. J Econ Behav Organ. 2013;86(0):137–47. doi:10.1016/j.jebo.2012.12.007.

Carson R. Contingent valuation: a comprehensive bibliography and history. Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar; 2011.

Carson R, Czajkowski M. The discrete choice experiment approach to environmental contingent valuation. In: Hess S, Daly A, editors. Handbook of choice modelling. Forthcoming.

Natter M, Feurstein M. Real world performance of choice-based conjoint models. Euro J Oper Res. 2002;137(2):448–58. doi:10.1016/S0377-2217(01)00147-3.

Kamakura W, Ozer M. A multi-trait multi-method validity test of partworth estimates. In: Gustafsson A, Hermann A, Huber F, editors. Conjoint measurement: methods and applications. Berlin: Springer; 2000.

Mueller S, Osidacz P, Francis IL, Lockshin L. Combining discrete choice and informed sensory testing in a two-stage process: can it predict wine market share? Food Qual Pref. 2010;21(7):741–54. doi:10.1016/j.foodqual.2010.06.008.

Araña JE, León CJ. Dynamic hypothetical bias in discrete choice experiments: evidence from measuring the impact of corporate social responsibility on consumers demand. Ecol Econ. 2013;87:53–61. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2012.12.005.

Horsky D, Nelson P, Posavac SS. Stating preference for the ethereal but choosing the concrete: how the tangibility of attributes affects attribute weighting in value elicitation and choice. J Consum Psychol. 2004;14(1–2):132–40. doi:10.1207/s15327663jcp1401&2_15.

Lusk JL, Norwood FB. Bridging the gap between laboratory experiments and naturally occurring markets: an inferred valuation method. J Environ Econ Manag. 2009;58(2):236–50. doi:10.1016/j.jeem.2008.12.003.

Mark TL, Swait J. Using stated preference and revealed preference modeling to evaluate prescribing decisions. Health Econ. 2004;13(6):563–73. doi:10.1002/hec.845.

Viney R, Savage E, Louviere J. Empirical investigation of experimental design properties of discrete choice experiments in health care. Health Econ. 2005;14(4):349–62. doi:10.1002/hec.981.

Ryan M, Watson V. Comparing welfare estimates from payment card contingent valuation and discrete choice experiments. Health Econ. 2009;18(4):389–401. doi:10.1002/hec.1364.

Kesternich I, Heiss F, McFadden D, Winter J. Suit the action to the word, the word to the action: hypothetical choices and real decisions in Medicare Part D. J Health Econ. 2013;32:1313–24. doi:10.1016/j.jhealeco.2012.11.006.

San Miguel F, Ryan M, Amaya-Amaya M. ‘Irrational’ stated preferences: a quantitative and qualitative investigation. Health Econ. 2005;14(3):307–22.

Lancsar E, Louviere J. Deleting ‘irrational’ responses from discrete choice experiments: a case of investigating or imposing preferences? Health Econ. 2006;15(8):797–811.

Ryan M, Watson V, Entwistle V. Rationalising the ‘irrational’: a think aloud study of discrete choice experiment responses. Health Econ. 2009;18(3):321–36. doi:10.1002/hec.1369.

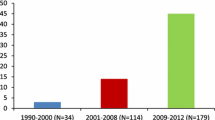

de Bekker-Grob EW, Ryan M, Gerard K. Discrete choice experiments in health economics: a review of the literature. Health Econ. 2012;21(2):145–72. doi:10.1002/hec.1697.

Kennedy CA. Revealed preference valuation compared to contingent valuation: radon-induced lung cancer prevention. Health Econ. 2002;11(7):585–98. doi:10.1002/hec.724.

Blumenschein K, Johannesson M, Yokoyama KK, Freeman PR. Hypothetical versus real willingness to pay in the health care sector: results from a field experiment. J Health Econ. 2001;20(3):441–57. doi:10.1016/S0167-6296(01)00075-3.

Hall J, Kenny P, King M, Louviere J, Viney R, Yeoh A. Using stated preference discrete choice modelling to evaluate the introduction of varicella vaccination. Health Econ. 2002;11:457–65.

Manski C. The structure of random utility models. Theory Decision. 1977;8:229–54.

Swait J, Ben-Akiva M. Incorporating random constraints in discrete models of choice set generation. Transp Res Part B Methodol. 1987;21(2):91–102. doi:10.1016/0191-2615(87)90009-9.

Swait J, Ben-Akiva M. Empirical test of a constrained choice discrete model: mode choice in São Paulo, Brazil. Transp Res Part B Methodol. 1987;21(2):103–15. doi:10.1016/0191-2615(87)90010-5.

Lancaster K. A new approach to consumer theory. J Polit Econ. 1966;74:132–57.

Andrews R, Srinivasan T. Studying consideration effects in empirical choice models using scanner panel data. J Mark Res. 1995;XXXII:30–45.

Andrews R, Ainslie A, Currim I. On the recoverability of choice behaviors with random coefficient and choice models in the context of limited data and unobserved effects. Manag Sci. 2008;54(1):83–99.

Adamowicz W, Swait J. Are food choices really habitual? Integrating habits, variety seeking and compensatory choice in a utility maximizing framework. Am J Agric Econ. 2012;95(1):17–24.

Lucas RE. Econometric policy evaluation: a critique. In: Brunner K, Meltzer H, editors. The Phillips Curve and Labour Markets, Cargenie-Rochester Converence Series on Public Policy 1, 19–46. Reprinted in R.E. Lucas, JR. Studies in modern business cycle theory. Cambridge, MA: MIT press; 1976.

Coast J, Horrocks S. Developing attributes and levels for discrete choice experiments using qualitative methods. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2007;12(1):25–30.

Louviere J, Marley A, Flynn T. Best worst scaling: theory and applications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; Forthcoming.

Lancsar E, Wildman J, Donaldson C, Ryan M, Baker R. Deriving distributional weights for QALYs through discrete choice experiments. J Health Econ. 2011;30(2):466–78. doi:10.1016/j.jhealeco.2011.01.003.

Swait J. A non-compensatory choice model incorporating attribute cutoffs. Transp Res Part B Methodol. 2001;35(10):903–28.

Elrod T, Johnson RD, White J. A new integrated model of noncompensatory and compensatory decision strategies. Organ Behav Human Decision Process. 2004;95(1):1–19. doi:10.1016/j.obhdp.2004.06.002.

Castro M, Martinez F, Munizaga M. Estimation of a constrained multinomial logit model. Transportation. 2013;40:563–81.

Fiebig DG, Haas M, Hossain I, Street DJ, Viney R. Decisions about Pap tests: what influences women and providers? Social Sci Med. 2009;68(10):1766–74. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.03.002.

Johnson FR, Lancsar E, Marshall D, Kilambi V, Muhlbacher A, Bridges J, et al. Constructing experimental design for choice-format conjoint analysis studies: a report of the ISPOR Conjoint Analysis Experimental Design Task Force. Value Health. 2013;16:3–13.

Lancsar E, Louviere J. Conducting discrete choice experiments to inform healthcare decision making: a user’s guide. PharmacoEconomics. 2008;26(8):661–77.

Hole AR. A discrete choice model with endogenous attribute attendance. Econ Lett. 2011;110:203–5.

Ryan M, Netten A, Skatun D, Smith P. Using discrete choice experiments to estimate a preference-based measure of outcome: an application to social care for older people. J Health Econ. 2006;25:927–44.

Ratcliffe J, Brazier J, Tsuchiya A, Symmonds T, Brown M. Using DCE and ranking data to estimate cardinal values for health states for deriving a preference-based single index from the sexual quality of life questionnaire. Health Econ. 2009;18:1261–76.

Bansback N, Brazier J, Tsuchiya A, Anis A. Using a discrete choice experiment to estimate health state utility values. J Health Econ. 2012;31:306–18.

Sivey P, Scott A, Witt J, Joyce C, Humphreys J. Junior doctors’ preferences for specialty choice. J Health Econ. 2012;31:813–23.

King MT, Hall J, Lancsar E, Fiebig D, Hossain I, Louviere J, et al. Patient preferences for managing asthma: results from a discrete choice experiment. Health Econ. 2007;16(7):703–17. doi:10.1002/hec.1193.

Lancsar E, Hall J, King M, Kenny P, Louviere J, Fiebig D, et al. Using discrete choice experiments to investigate subject preferences for preventive asthma medication. Respirology. 2007;12(1):127–36.

Fiebig D. Discrete choice experiments in health economics: opportunities in a data deluge. International Choice Modelling Conference; Sydney, Australia; 2013.

Acknowledgments

Both authors declare no financial or non-financial conflicts of interest. This paper was undertaken in response to an invitation from PharmacoEconomics. The paper was conceived, written and revised jointly by EL and JS.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lancsar, E., Swait, J. Reconceptualising the External Validity of Discrete Choice Experiments. PharmacoEconomics 32, 951–965 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-014-0181-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-014-0181-7