Abstract

Background

This study aimed to understand how respondents from three Asian countries interpret and perceive the EuroQol Visual Analogue Scale (EQ-VAS).

Method

Data were from a project that aimed to examine the cultural appropriateness of EQ-5D in Asia. Members of the general public from China, Japan, and Singapore were interviewed one-to-one in their preferred languages. Open-ended questions (e.g. What does “best imaginable health” mean to you?) were used to elicit participants’ interpretation of the labels of EQ-VAS. How the scale could be improved was also probed. Thematic and content analyses were performed separately for each country before pooling for comparison.

Results

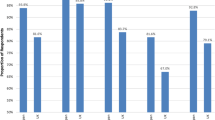

Sixty Chinese, 24 Japanese, and 60 Singaporeans were interviewed. Interpretations of the label “Best Imaginable Health” varied among the participants. Interestingly, some participants indicated that “Best Imaginable Health” is unachievable. Interpretations for “Worst Imaginable Health” also varied, with participants referring primarily to one of three themes, namely, “death,” “disease,” and “disability.” There were different opinions as to what changes in health would correspond to a 5- to 10-point change on the EQ-VAS. While participants opined that EQ-VAS is easy to understand, some criticized it for being too granular and that scale labels are open to interpretation. Findings from the three countries were similar.

Conclusion

It appears that interpretations of the EQ-VAS vary across Asian respondents. Future studies should investigate whether the variations are associated with any respondent characteristics and whether the EQ-VAS could be modified to achieve better respondent acceptance.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Devlin NJ, Brooks R. EQ-5D and the EuroQol group: past, present and future. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2017;15(2):127–37.

EQ-5D-5L User Guide. 2019. https://euroqol.org/publications/user-guides/. Accessed 29 May 2020.

Qian X. Tan RL-Y, Chuang L-H, Luo N. Measurement properties of commonly used generic preference-based measures in East and South-East Asia: a systematic review. PharmacoEconomics. 2020;38:159–70.

Vaismoradi M, Turunen H, Bondas T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs Health Sci. 2013;15(3):398–405.

Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62(1):107–15.

Torrance GW, Feeny D, Furlong W. Visual analog scales: do they have a role in the measurement of preferences for health states?. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications Sage CA; 2001.

Fox-Rushby J, Selai C. What concepts does the EQ-5D measure? Intentions and interpretations. In: Brooks R, editor. The measurement and valuation of health status using EQ-5D: a European perspective. Dordrecht: Springer; 2003. p. 167–82.

Busschbach J, Hessing D, de Charro F. Observations on one hundred students filling in the EuroQol questionnaire. In: Kind P, editor. EQ-5D concepts and methods: a developmental history. Dordrecht: Springer; 2005. p. 81–90.

Luo N, Cang S-Q, Quah H-MJ, How C-H, Tay EG. The discriminative power of the EuroQol visual analog scale is sensitive to survey language in Singapore. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2012;10(1):32.

Koh D, Bin Abdullah AMK, Wang P, Lin N, Luo N. Validation of Brunei’s Malay EQ-5D questionnaire in patients with type 2 diabetes. PloS One. 2016;11(11):e0165555.

Jaeschke R, Guyatt G, Keller J, Singer J. Measurement of health status: ascertaining the meaning of a change in quality-of-life questionnaire score. Control Clin Trials. 1989;10:407–15.

Luo N, Chew L-H, Fong K-Y, Koh D-R, Ng S-C, Yoon K-H, et al. Do English and Chinese EQ-5D versions demonstrate measurement equivalence? An exploratory study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1(1):7.

Chen P, Lin K-C, Liing R-J, Wu C-Y, Chen C-L, Chang K-C. Validity, responsiveness, and minimal clinically important difference of EQ-5D-5L in stroke patients undergoing rehabilitation. Qual Life Res. 2016;25(6):1585–96.

Zanini A, Aiello M, Adamo D, Casale S, Cherubino F, Della Patrona S, et al. Estimation of minimal clinically important difference in EQ-5D visual analog scale score after pulmonary rehabilitation in subjects with COPD. Respir Care. 2015;60(1):88–95.

Devlin NJ, Hansen P, Selai C. Understanding health state valuations: a qualitative analysis of respondents' comments. Qual Life Res. 2004;13(7):1265–77.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This study was funded by the EuroQol Group (EQ Project 2016290) and the Humanities and Social Sciences (HSS) Seed Fund from the National University of Singapore (1/2019).

Conflict of interest

Nan Luo, Michael Herdman, Zhihao Yang and Ataru Igarshi are members of the Euroqol Group. Rachel Lee-Yin Tan declare no conflict of interests.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee (NUS-IRB Ref No.: S-19-129E and B-16-252) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the studies.

Consent for publication

As part of informed consent for the study, participants gave consent for publication of the data derived from their participation in the research study.

Availability of data and material

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code Availability

NA.

Author contributions

NL and MH contributed to the study conception and design. AI and ZY collected the data in Japan and China respectively. RL-YT consolidated and analyzed the data. The first draft of the manuscript was written by RL-YT. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tan, R.LY., Yang, Z., Igarashi, A. et al. How Do Respondents Interpret and View the EQ-VAS? A Qualitative Study of Three Asian Populations. Patient 14, 283–293 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-020-00452-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-020-00452-5