Abstract

Background

Depression and physical function are particularly important health domains for the elderly. The Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) and the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS®) physical function item bank are two surveys commonly used to measure these domains. It is unclear if these two instruments adequately measure these aspects of health in minority elderly.

Objective

The aim of this study was to estimate the readability of the GDS and PROMIS® physical function items and to assess their comprehensibility using a sample of African American and Latino elderly.

Methods

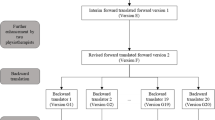

Readability was estimated using the Flesch–Kincaid and Flesch Reading Ease (FRE) formulae for English versions, and a Spanish adaptation of the FRE formula for the Spanish versions. Comprehension of the GDS and PROMIS® items by minority elderly was evaluated with 30 cognitive interviews.

Results

Readability estimates of a number of items in English and Spanish of the GDS and PROMIS® physical functioning items exceed the U.S. recommended 5th-grade threshold for vulnerable populations, or were rated as ‘fairly difficult’, ‘difficult’, or ‘very difficult’ to read. Cognitive interviews revealed that many participants felt that more than the two (yes/no) GDS response options were needed to answer the questions. Wording of several PROMIS® items was considered confusing, and interpreting responses was problematic because they were based on using physical aids.

Conclusions

Problems with item wording and response options of the GDS and PROMIS® physical function items may reduce reliability and validity of measurement when used with minority elderly.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Blazer D, Williams CD. Epidemiology of dysphoric and depression in an elderly population. Am J Psychiatry. 1980;137:439–44.

Macdonald AJD. Mental health in old age. BMJ. 1997;315:413–7.

Balfour JL, Kaplan GA. Neighborhood environment and loss of physical function in older adults: evidence from the Alameda County Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;155:507–15.

West LA, Cole S, Goodkind D, et al. 65+ in the United States: 2010. Special studies. Current population reports. US Department of Health and Human Services, US Department of Commerce, United States Census Bureau. 2014. Available at: http://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2014/demo/p23-212.pdf. Accessed 2 June 2016.

Chang C-H, Wright BD, Cella D, Hays RD. The SF-36 physical and mental health factors were confirmed in cancer and HIV/AIDS patients. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60:68–72.

A profile of older Americans: 2011. Administration on aging. US Department of Health and Human Services. 2011. Available at http://www.aoa.gov/Aging_Statistics/Profile/2011/docs/2011profile.pdf. Accessed 2 June 2016.

US Census Bureau projections show a slower growing, older, more diverse nation a half century from now. United States Census Bureau. 2012. Available at https://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/population/cb12-243.html. Accessed 2 June 2016.

Passel JS, Cohn DV. US population projections: 2005–2050. Pew Research Center. 2008. Available at: http://pewsocialtrends.org/files/2010/10/85.pdf. Accessed 2 June 2016.

Stewart AL, Napoles-Springer AM. Health-related quality-of-life assessments in diverse population groups in the United States. Med Care. 2000;38(9 Suppl):II102–24.

Stewart L, Napoles-Springer AM. Advancing health disparities research: can we afford to ignore measurement issues? Med Care. 2003;41(11):1207–20.

Hargraves LJ, Hadley J. The contribution of insurance coverage and community resources to reducing racial/ethnic disparities in access to care. Health Serv Res. 2003;38:809.

Lubben JE, Weiler PG, Chi I. Health practices of the elderly poor. Am J Public Health. 1989;79:731–4.

Economic Policy Institute. Majority of elderly Blacks and Hispanics are on the cusp of poverty, a new EPI report finds. Available at: http://www.epi.org/press/majority-elderly-blacks-hispanics-cusp-poverty/. Accessed 2 June 2016.

McWilliams JM. Health consequences of uninsurance among adults in the United States: recent evidence and implications. Milbank Q. 2009;87:443–94.

Deshpande PR, Rajan S, Sudeepthi BL, et al. Patient-reported outcomes: a new era in clinical research. Perspect Clin Res. 2011;2(4):137–44.

Calderon JL, Beltran RA. Pitfalls in health communication: healthcare policy, institution, structure, and process. MedGenMed. 2004;6(1):9.

Calderon JL, Zadshir A, Norris K. A survey of kidney disease and risk-factor information on the world wide web. MedGenMed. 2004;6(4):3.

Fongwa MN, Setodji CM, Paz SH, et al. Readability and missing data rates in CAHPS 2.0 Medicare Survey in African American and White Medicare respondents. Health Outcomes Res Med. 2010;1(1):e39–49.

Johnson C. Proposal guidelines for new content on the 2007–2008 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). 13 Dec 2006. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/proposal_guidelines_2007-8.pdf. Accessed 2 June 2016.

Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, et al. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res. 1983;17:37–49.

Greenberg SA. The Geriatric Depression Scale. The Hartford Institute for Geriatric Nursing, New York University, College of Nursing. Available at: https://consultgeri.org/try-this/general-assessment/issue-4. Accessed 2 June 2016.

Rose M, Bjorner JB, Becker J, et al. Evaluation of a preliminary physical function item bank supported the expected advantages of the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS). J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61:17–33.

Bruce B, Fries JF, Ambrosini D, et al. Better assessment of physical function: item improvement is neglected but essential. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11(6):R191.

Hays RD, Spritzer KL, Amtmann D, et al. Upper-extremity and mobility subdomains from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) adult physical functioning item bank. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;94:2291–6.

Hays RD, Spritzer KL, Fries JF, et al. Responsiveness and minimally important difference for the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement and Information System (PROMIS) 20-item physical functioning short-form in a prospective observational study of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(1):104–7.

Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, et al. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res. 1983;17:37–49.

Instructional Web Server. The University of Western Ontario. BioPsychoSocial Assessment Tools for the Elderly—Assessment Summary Sheet. Available at: https://instruct.uwo.ca/kinesiology/9641/Assessments/Psychological/Ger_DS.html. Accessed 2 June 2016.

Burke WJ, Roccaforte WH, Wengel SP. The short form of the Geriatric Depression Scale: a comparison with the 30-item form. Recent evidence and development of a shorter version. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 1991;4:173–8.

Stanford/VA/NIA Aging Clinical Research Center (ACRC), Stanford University. Available at: https://web.stanford.edu/~yesavage/GDS.html. Accessed 2 June 2016.

Cella D, Riley W, Stone A, et al. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(11):1179–94.

Cella D, Hernandez L, Bonomi AE, et al. Spanish language translation and initial validation of the functional assessment of cancer therapy quality-of-life instrument. Med Care. 1998;36:1407–18.

Cella D, Gershon R, Bass M, et al. Assessment Center. PROMIS Health Organization. 2007–2013. Available at: https://www.assessmentcenter.net/documents/PROMIS%20Physical%20Function%20Scoring%20Manual.pdf. Accessed 2 June 2016.

PROMIS. Dynamic tools to measure health outcomes from the patient perspective. National Institutes of Health. Available at: http://www.nihpromis.org/. Accessed 2 June 2016.

Meade C, Smith C. Readability formulas: cautions and criteria. Patient Educ Couns. 1991;17:153–8.

Pinero-Lopez MA, Modamio CP, Fernandez-Lastra C, et al. Quality health information: readability-measurement formulas for English and Spanish written materials. Eur J Clin Pharm. 2013;15(2):136–9.

Willis GB. Cognitive interviewing: a tool for improving questionnaire design. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2005.

Blair J, Brick PD. Methods for the analysis of cognitive interviews. Available at: https://www.amstat.org/sections/srms/proceedings/y2010/Files/307865_59514.pdf. Accessed 2 June 2016.

Knafl K, Deatrick J, Gallo A, et al. The analysis and interpretation of cognitive interviews for instrument development. Res Nurs Health. 2007;30(2):224–34.

Calderon JL, Morales LS, Liu H, et al. Variation in the readability of items within surveys. Am J Med Qual. 2006;21(1):49–56.

Nutbeam D. Defining and measuring health literacy: what can we learn from literacy studies? Int J Public Health. 2009;54:303–5.

Clerehan R, Buchbinder R, Moodie J. A linguistic framework for assessing the quality of written patient information: its use in assessing methotrexate information for rheumatoid arthritis. Health Educ Res. 2005;20(3):334–44.

Morales LS, Weidmer BO, Hays RD. Readability of CAHPS 2.0 child and adult core surveys. In: Lynamon ML, Kulka RA, editors. 7th conference on health survey research methods. Hyattsville: DHHS; 2001. Publication. no. (PHS) 01-1013. pp. 83–90.

Paz SH, Liu H, Fongwa MN, Morales LS, et al. Readability estimates for commonly used health-related quality of life surveys. Qual Life Res. 2009;18:889–900.

Ávila de Tomás JF, Veiga Paulet JA. Legibilidad de la información sanitariaofrecida a los ciudadanos. Una paroximación a través del Índice de Flesch. Centro de Salud. 2002;(Diciembre):589-597.

Calderón JL, Fleming E, Gannon MR, et al. Applying an expanded set of cognitive design principles to formatting the Kidney Early Evaluation Program (KEEP) longitudinal survey. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;51(4 Suppl 2):S83–92.

Mullin PA, Lohr KN, Bresnahan BW, et al. Applying cognitive design principles to formatting HRQOL instruments. Qual Life Res. 2000;9(1):13–27.

Krosnick JA, Alwin DF. An evaluation of a cognitive theory of response-order effects in survey measurement. Public Opin Q. 1987;51:201–19.

Lesher EL, Berryhill JS. Validation of the Geriatric Depression Scale—Short Form among inpatients. J Clin Psychol. 1994;50(2):256–60.

Kohout F, Berkman L, Evans D, et al. Two shorter forms of the CES-D Depression Symptoms Index. J Aging Health. 1993;5(2):179–93.

Amtmann D, Bamer A, Cook K, et al. Adapting PROMIS physical function items for users of assistive technology. Disabil Health J. 2010;3(2):e9.

Paz SH, Spritzer KL, Morales LS, et al. Evaluation of the Patient-Reported Outcomes Information System (PROMIS®) Spanish-Language Physical Functioning Items. Qual Life Res. 2013;22(7):1819–30.

Paz SH, Spritzer KL, Morales LS, et al. Age-related differential item functioning for the Patient-Reported Outcomes Information System (PROMIS®) Physical Functioning Items. Prim Health Care. 2013;3(131):12086. doi:10.4172/2167-1079.1000131

Lynch AD, Dodds NE, Yu L, et al. Individuals with knee impairments identify items in need of clarification in the Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS®) pain interference and physical function item banks: a qualitative study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2016;14(1):77.

Author contributions

Sylvia H. Paz helped design the study, collected and analyzed the data, wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and wrote intermediate versions following co-author revisions. Loretta Jones helped design the study and provided input for the manuscript. José L. Calderón provided input in several revisions of the manuscript. Ron D. Hays helped with the study design and provided input throughout the study and writing of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Sylvia H. Paz, José L. Calderón, and Ron D. Hays received support from the UCLA and Charles Drew University (CDU), Resource Centers for Minority Aging Research/Center for Health Improvement of Minority Elderly (RCMAR/CHIME) under National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Aging (NIH/NIA) grant P30-AG021684. Sylvia H. Paz was also supported by the UCLA Clinical and Translational Science Institute (CTSI) under NIH/National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) grant number UL1TR000124. Ron D. Hays was also supported by NCI (No. 1U2-CCA186878-01), and the UCLA/CDU Project EXPORT, National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD; 2P20MD000182). Loretta Jones was supported in part by NIH/NIMHD grant numbers U54MD007598 (formerly U54RR026138), P20MD00182, S21 MD000103, MD000182, U54RR022762, and R01MD007721-01A1, NIH/NCATS grant number UL1TR000124, and NIH/NIA RCMAR/CHIME grant number P30-AG021684. The Los Angeles Community Academic Partnership for Research in Aging (L.A. Capra) Center and Ward Economic Development Corporation (WEDC) were instrumental in providing community organizations. The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Conflict of interest

Sylvia H. Paz, Loretta Jones, José L. Calderón, and Ron D. Hays have no conflicts of interest to declare. The study was approved by the UCLA Institutional Review Board (IRB) Research Ethics Committee and has been performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix

Appendix

English Instruments and Readability Scores

PROMIS® Physical Function Short Form (20a)

FRE | F-K | ||

|---|---|---|---|

PFA11 | Are you able to do chores such as vacuuming or yard work? | 81.8 | 4.8 |

PFA12 | Are you able to push open a heavy door? | 84.9 | 3.6 |

PFA16 | Are you able to dress yourself, including tying shoelaces and buttoning your clothes? | 63.4 | 7.6 |

Are you able to dress yourself, including tying shoelaces and doing buttons? | 67.7 | 6.7 | |

PFA34 | Are you able to wash your back? | 100.00 | 0.6 |

PFA38 | Are you able to dry your back with a towel? | 95.1 | 2.4 |

PFA51 | Are you able to sit on the edge of a bed? | 100.0 | 1.5 |

PFA55 | Are you able to wash and dry your body? | 94.3 | 2.3 |

PFA56 | Are you able to get in and out of a car? | 100.0 | 1.5 |

PFB19 | Are you able to squeeze a new tube of toothpaste? | 95.1 | 2.4 |

PFB22 | Are you able to hold a plate full of food? | 100.0 | 1.2 |

PFB24 | Are you able to run a short distance, such as to catch a bus? | 95.9 | 3.3 |

PFB26 | Are you able to shampoo your hair? | 90.9 | 2.3 |

PFC45 | Are you able to sit on and get up from the toilet? | 95.9 | 2.8 |

Are you able to get on and off the toilet? | 95.1 | 2.4 | |

PFC46 | Are you able to transfer from a bed to a chair and back? | 96.0 | 3.0 |

PFA1 | Does your health now limit you in doing vigorous activities, such as running, lifting heavy objects, participating in strenuous sports? | 34.2 | 12.0 |

PFA3 | Does your health now limit you in bending, kneeling, or stooping? | 80.3 | 4.7 |

PFA5 | Does your health now limit you in lifting or carrying groceries? | 72.6 | 5.8 |

PFC12 | Does your health now limit you in doing two hours of physical labor? | 83.0 | 4.9 |

PFC36 | Does your health now limit you in walking more than a mile (1.6 km)? | 83.8 | 5.0 |

Does your health now limit you in walking more than a mile? | 95.9 | 2.8 | |

PFC37 | Does your health now limit you in climbing one flight of stairs? | 95.9 | 2.8 |

Additional Items to Complete Short Forms 4a, 8a, 10a, and PROMIS® PF-57

FRE | F-K | ||

|---|---|---|---|

PFA21 | Are you able to go up and down stairs at a normal pace? | 96.0 | 3.0 |

PFA23 | Are you able to go for a walk of at least 15 minutes? | 89.8 | 4.1 |

PFC53 | Are you able to run errands and shop? | 94.3 | 2.3 |

PFA7 | How much do physical health problems now limit your usual physical activities (such as walking or climbing stairs)? | 40.0 | 9.6 |

PFB1 | Does your health now limit you in doing moderate work around the house like vacuuming, sweeping floors or carrying in groceries? | 57.6 | 10.6 |

PFA4 | Does your health now limit you in doing heavy work around the house like scrubbing floors, or lifting or moving heavy furniture? | 65.7 | 9.7 |

Geriatric Depression Scale

FRE | F-K | ||

|---|---|---|---|

Q.1 | Are you basically satisfied with your life? | 54.7 | 7.3 |

Q.2 | Have you dropped many of your activities and interests? | 56.7 | 7.5 |

Q.3 | Do you feel that your life is empty? | 100.0 | 0.8 |

Q.4 | Do you often get bored? | 100.0 | 0.5 |

Q.5 | Are you hopeful about the future? | 59.7 | 6.4 |

Q.6 | Are you bothered by thoughts you can t get out of your head? | 100.0 | 1.2 |

Q.7 | Are you in good spirits most of the time? | 100.0 | 1.0 |

Q.8 | Are you afraid that something bad is going to happen to you? | 81.8 | 4.8 |

Q.9 | Do you feel happy most of the time? | 100.0 | 0.8 |

Q.10 | Do you often feel helpless? | 83.3 | 2.8 |

Q.11 | Do you often get restless and fidgety? | 66.7 | 5.6 |

Q.12 | Do you prefer to stay at home, rather than going out and doing new things? | 95.7 | 3.6 |

Q.13 | Do you frequently worry about the future? | 54.7 | 7.3 |

Q.14 | Do you feel you have more problems with memory than most? | 87.9 | 3.7 |

Q.15 | Do you think it is wonderful to be alive now? | 86.7 | 3.6 |

Q.16 | Do you often feel downhearted and blue? | 78.8 | 3.9 |

Q.17 | Do you feel pretty worthless the way you are now? | 95.1 | 2.4 |

Q.18 | Do you worry a lot about the past? | 92.9 | 2.2 |

Q.19 | Do you find life very exciting? | 73.8 | 4.4 |

Q.20 | Is it hard for you to get started on new projects? | 95.6 | 2.6 |

Q.21 | Do you feel full of energy? | 87.9 | 2.4 |

Q.22 | Do you feel that your situation is hopeless? | 71.8 | 5.2 |

Q.23 | Do you think that most people are better off than you are? | 95.9 | 2.8 |

Q.24 | Do you frequently get upset over little things? | 61.2 | 6.7 |

Q.25 | Do you frequently feel like crying? | 87.9 | 2.4 |

Q.26 | Do you have trouble concentrating? | 49.4 | 7.6 |

Q.27 | Do you enjoy getting up in the morning? | 82.3 | 3.7 |

Q.28 | Do you prefer to avoid social gatherings? | 54.7 | 7.3 |

Q.29 | Is it easy for you to make decisions? | 82.3 | 3.7 |

Q.30 | Is your mind as clear as it used to be? | 100.0 | 0.1 |

Spanish Instruments and Readability Scores

PROMIS® Physical Function Short Form (20a)

FREa | ||

|---|---|---|

PFA11 | ¿Puede realizar tareas, como pasar la aspiradora o trabajar en el jardín? | 10.1 |

PFA12 | ¿Puede abrir una puerta pesada empujándola? | 11.8 |

PFA16 | ¿Puede vestirse sin ayuda, incluso amarrarse los zapatos y abotonarse la ropa? | 11.4 |

PFA34 | ¿Puede lavarse la espalda? | 8.8 |

PFA38 | ¿Puede secarse la espalda con una toalla? | 8.2 |

PFA51 | ¿Puede sentarse en el borde de una cama? | 6.5 |

PFA55 | ¿Puede lavarse y secarse el cuerpo? | 7.3 |

PFA56 | ¿Se puede subir y bajar de un automóvil? | 6.5 |

PFB19 | ¿Puede apretar un tubo nuevo de pasta de dientes? | 6.8 |

PFB22 | ¿Puede sujetar un plato lleno de comida? | 7.6 |

PFB24 | ¿Puede correr una distancia corta, como para alcanzar un autobús? | 9.6 |

PFB26 | ¿Puede lavarse el cabello con champú? | 7.3 |

PFC45 | ¿Puede sentarse y levantarse del inodoro (excusado)? | 12.1 |

PFC46 | ¿Puede pasar de una cama a una silla y volver a la cama? | 6.5 |

PFA1 | ¿Limita su salud en este momento su capacidad para realizar actividades vigorosas, como correr, levantar objetos pesados o participar en deportes enérgicos? | 15.2 |

PFA3 | ¿Limita su salud en este momento su capacidad para inclinarse, arrodillarse o agacharse? | 12.3 |

PFA5 | ¿Limita su salud en este momento su capacidad para levantar o llevar las bolsas del supermercado? | 10.5 |

PFC12 | ¿Limita su salud en este momento su capacidad para realizar dos horas de trabajo físico? | 10.9 |

PFC36 | ¿Limita su salud en este momento su capacidad para caminar más de una milla (1.6 km)? | 8.9 |

¿Limita su salud en este momento su capacidad para caminar más de una milla? | 10.0 | |

PFC37 | ¿Limita su salud en este momento su capacidad para subir un piso de escaleras? | 10.0 |

Additional Items to Complete Short Forms 4a, 8a, 10a, and PROMIS® PF-57

FREa | ||

|---|---|---|

PFA21 | ¿Puede subir y bajar escaleras a un paso normal? | 7.4 |

PFA23 | ¿Puede salir a caminar durante 15 minutos por lo menos? | 8.3 |

PFA53 | ¿Puede hacer mandados y compras? | 7.1 |

PFA7 | ¿Cuánto le limitaron sus problemas de salud física sus actividades físicas usuales (como caminar o subir escaleras)? | 12.6 |

PFB1 | ¿Limita su salud en este momento su capacidad para realizar trabajos moderados en el hogar, como pasar la aspiradora, barrer el piso (suelo) o entrar a la casa las compras del mercado? | 13.8 |

PFA4 | ¿Limita su salud en este momento su capacidad para realizar trabajos pesados en el hogar, como fregar (restregar) los pisos (el suelo), o levantar o mover muebles pesados? | 13.4 |

Geriatric Depression Scale

FREa | ||

|---|---|---|

Q.1 | ¿Esta usted satisfecho con su vida? | 7.3 |

Q.2 | ¿Ha usted abandonado muchos de sus intereses y actividades? | 10.7 |

Q.3 | ¿Siente usted que su vida esta vacia? | 6.9 |

Q.4 | ¿Se siente usted frequentemente aburrido? | 12.2 |

Q.5 | ¿Tiene usted mucha fe en el futuro? | 5.6 |

Q.6 | ¿Tiene usted pensamientos que le molestan? | 8.6 |

Q.7 | ¿La mayoria del tiempo esta usted de buen humor? | 6.8 |

Q.8 | ¿Tiene miedo que algo malo le vaya a pasar? | 6.1 |

Q.9 | ¿Se siente usted feliz la mayoria del tiempo? | 7.2 |

Q.10 | ¿Se siente usted a menudo impotente? | 8.6 |

Q.11 | ¿Se siente usted a menudo intranquilo? | 8.6 |

Q.12 | ¿Prefiere usted quedarse en su cuarto en vez de salir? | 6.4 |

Q.13 | ¿Se preocupa usted a menudo sobre el futuro? | 8.5 |

Q.14 | ¿Cree usted que tiene mas problemas con su memoria que los demas? | 6.9 |

Q.15 | ¿Cree usted que es maravilloso ester viviendo? | 9.5 |

Q.16 | ¿Se siente usted a menudo trlste? | 6.0 |

Q.17 | ¿Se siente usted inutil, echadizo? | 9.7 |

Q.18 | ¿Se preocupa usted mucho sobre el pasado? | 8.2 |

Q.19 | ¿Cree usted que la vida es muy interesante? | 7.2 |

Q.20 | ¿Es dificil para usted empezar proyectos nuevos? | 9.5 |

Q.21 | ¿Se siente usted lleno de energla? | 7.3 |

Q.22 | ¿Se siente usted sin esperanza? | 7.1 |

Q.23 | ¿Cree usted que los demas tienen mas suerte que usted? | 5.7 |

Q.24 | ¿Se siente usted muy nervioso sobre cosas pequenas? | 7.8 |

Q.25 | ¿Siente usted a menudo ganas de llorar? | 6.9 |

Q.26 | ¿Es dificil pare usted concentrarse? | 9.7 |

Q.27 | ¿Esta usted contento de levantarse por la manana? | 8.5 |

Q.28 | ¿Prefiere usted evitar grupos de gente? | 8.6 |

Q.29 | ¿Es facil pare usted tomar decisiones? | 8.6 |

Q.30 | ¿Esta su mente tan clara como antes? | 5.6 |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Paz, S.H., Jones, L., Calderón, J.L. et al. Readability and Comprehension of the Geriatric Depression Scale and PROMIS® Physical Function Items in Older African Americans and Latinos. Patient 10, 117–131 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-016-0191-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-016-0191-y