Abstract

Background

Data describing patients’ priorities, or main concerns, are essential to inform important decisions in healthcare, including treatment planning, diagnostic testing, and the development of programs to improve access and delivery of care. To date, the majority of studies performed does not account for variability in patients’ priorities, and as a consequence may not effectively inform end users. The objective of this study was to examine the value of segmentation analysis as a method to illustrate variability in priorities for treatment of chronic hepatitis C (HCV).

Methods

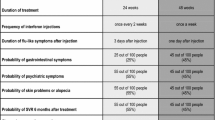

We elicited patients’ main concerns when considering antiviral therapy for HCV using a Best–Worst Scaling experiment (Case 1) with ten objects. Latent class analysis was used to estimate part-worth utilities and the probability that each respondent belongs to each segment.

Results

In the aggregate, subjects (N = 162) had three main concerns: (1) not being cured; (2) experiencing a lot of side effects; and (3) developing viral resistance to therapy. Segmentation into two groups demonstrated that both groups prioritized the likelihood of cure and coping with side effects, but that only one group (n = 78) was concerned about developing viral resistance to therapy, while subjects in the second group (n = 84) prioritized being able to keep up with their responsibilities. Further segmentation revealed distinct clusters of patients with unique priorities.

Conclusions

Patients’ priorities vary significantly. Preference studies should consider including methods to determine whether distinct clusters of priorities and/or concerns exist in order to accurately inform end users’ decision making.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Bridges JFP. Stated preference methods in health care evaluation: an emerging methodological paradigm in health economics. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2003;2:213–24.

Bridges JFP, Onukwugha E, Johnson FR, Hauber AB. Patient preference methods: a patient-centered evaluation paradigm. ISPOR Connect. 2007;13:4–7.

Flynn TN, Louviere JJ, Peters TJ, Coast J. Best–worst scaling: what it can do for health care research and how to do it. J Health Econ. 2007;26:171–89.

Ryan M, Farrar S. Using conjoint analysis to elicit preferences for health care. BMJ. 2000;320:1530–3.

Constantinescu F, Goucher S, Weinstein A, Fraenkel L. Racial disparities in treatment preferences for rheumatoid arthritis. Med Care. 2009;47:350–5.

Fraenkel L, Cunningham M, Peters E. Subjective numeracy and preference to stay with the status quo. Med Decis Mak. 2015;35:6–11.

Rosen HR. Chronic hepatitis C infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2429–38.

Shiratori Y, Imazeki F, Moriyama M, Yano M, Arakawa Y, Yokosuka O, et al. Histologic improvement of fibrosis in patients with hepatitis C who have sustained response to interferon therapy. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132:517–24.

Shindo M, Hamada K, Oda Y, Okuno T. Long-term follow-up study of sustained biochemical responders with interferon therapy. Hepatology. 2001;33:1299–302.

Kasahara A, Hayashi N, Mochizuki K, Takayanagi M, Yoshioka K, Kakumu S, et al. Risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma and its incidence after interferon treatment in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 1998;27:1394–402.

Yoshida H, Arakawa Y, Sata M, Nishiguchi S, Yano M, Fujiyama S, et al. Interferon therapy prolonged life expectancy among chronic hepatitis C patients. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:483–91.

Davis GL, Alter MJ, El-Serag H, Poynard T, Jennings LW. Aging of hepatitis C virus (HCV)-infected persons in the United States: a multiple cohort model of HCV prevalence and disease progression. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:513–21.

Finn A, Louviere JJ. Determining the appropriate response to evidence of public concern: the case of food safety. J Public Policy Mark. 1992;11:12–25.

Flynn TN, Marley AAJ. Best-worst scaling: theory and methods. In: Hess S, Daly A, editors. Handbook of choice modeling. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited; 2014. p. 178–201.

Bridges JF, Joy S, Gallego G, Blauvelt BM, Geschwind JF, Pawlik T. Priorities for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) control: a comparison of policy needs in five European countries. J Comp Policy Anal Res Pract. 2012;14:352–68.

Ross M, Bridges JF, Ng X, Wagner LD, Frosch E, Reeves G, et al. A best-worst scaling experiment to prioritize caregiver concerns about ADHD medication for children. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66:208–11.

Imaeda A, Bender D, Fraenkel L. What is most important to patients when deciding about colorectal screening? J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:688–93.

Najafzadeh M, Lynd LD, Davis JC, Bryan S, Anis A, Marra M, et al. Barriers to integrating personalized medicine into clinical practice: a best-worst scaling choice experiment. Genet Med. 2012;14:520–6.

Ratcliffe J, Flynn T, Terlich F, Stevens K, Brazier J, Sawyer M. Developing adolescent-specific health state values for economic evaluation: an application of profile case best-worst scaling to the Child Health Utility 9D. Pharmacoeconomics. 2012;30:713–27.

Youden WJ. Use of incomplete block replications in estimating tobacco-mosaic virus. Contributions. Boyce Thompson Institute for Plant. Research. 1937;8:41–8.

Youden WJ. Experimental designs to increase accuracy of greenhouse studies. Contributions. Boyce Thompson Institute for Plant Research. 1940;11:219–28.

Deal K. Segmenting patients and physicians using preferences from discrete choice experiments. Patient. 2014;7:5–21.

Brown DS, Poulos C, Johnson FR, Chamiec-Case L, Messonnier ML. Adolescent girls’ preferences for HPV vaccines: a discrete choice experiment. Adv Health Econ Health Serv Res. 2014;24:93–121.

Carroll FE, Al-Janabi H, Flynn T, Montgomery AA. Women and their partners’ preferences for Down’s syndrome screening tests: a discrete choice experiment. Prenat Diagn. 2013;33:449–56.

Cunningham CE, Chen Y, Deal K, Rimas H, McGrath P, Reid G, et al. The interim service preferences of parents waiting for children’s mental health treatment: a discrete choice conjoint experiment. J Abnorm Child Psych. 2013;41:865–77.

Fraenkel L, Suter L, Cunningham CE, Hawker G. Understanding preferences for disease modifying drugs in osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2014;66:1186–92.

Goossens LM, Utens CM, Smeenk FW, Donkers B, van Schayck OC, Rutten-van Molken MP. Should I stay or should I go home? A latent class analysis of a discrete choice experiment on hospital-at-home. Value Health. 2014;17:588–96.

Guo N, Marra CA, FitzGerald JM, Elwood RK, Anis AH, Marra F. Patient preference for latent tuberculosis infection preventive treatment: a discrete choice experiment. Value Health. 2011;14:937–43.

Lagarde M. Investigating attribute non-attendance and its consequences in choice experiments with latent class models. Health Econ. 2013;22:554–67.

Naik-Panvelkar P, Armour C, Rose JM, Saini B. Patient preferences for community pharmacy asthma services: a discrete choice experiment. Pharmacoeconomics. 2012;30:961–76.

Waschbusch DA, Cunningham CE, Pelham WE, Rimas HL, Greiner AR, Gnagy EM, et al. A discrete choice conjoint experiment to evaluate parent preferences for treatment of young, medication naive children with ADHD. J Clin Child Adolescent Psychol. 2011;40:546–61.

Whitty JA, Stewart S, Carrington MJ, Calderone A, Marwick T, Horowitz JD, et al. Patient preferences and willingness-to-pay for a home or clinic based program of chronic heart failure management. PLoS One. 2013;8:e58347.

Wong YN, Egleston BL, Sachdeva K, Eghan N, Pirollo M, Stump TK, et al. Cancer patients’ trade-offs among efficacy, toxicity, and out-of-pocket cost in the curative and noncurative setting. Med Care. 2013;51:838–45.

Woodward AT. A latent class analysis of age differences in choosing service providers to treat mental and substance use disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64:1087–94.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The authors would like to thank Dorthe Welch and Lanette Errante for recruiting and interviewing the subjects for this study. We are, as always, indebted to the Veterans.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

This study was approved by the Veterans Administration Central Institutional Review Board and has been performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of interest

Drs. Fraenkel, Monto, and Bridges have no declaration of personal interests. Dr. Lim has served as consultant for Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, Janssen, and Merck, and has received research funding from Abbott, Achillion, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, and Janssen (paid to institution). Dr. Reyna has served on advisory groups, including committees of the National Academy of Sciences, Psychonomic Society, and other nonprofit organizations. She has been a paid consultant for Xerox. Dr. Garcia-Tsao has served as a consultant for Abbvie and Fibrogen, is Associate Editor for Hepatology, and serves on committees of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

Funding

This study was funded in full by the VA Health Services and Research Department (IIR 10-131).

Author contributions

Analyses were performed by Liana Fraenkel. All authors had a substantial role in the design of the study and writing the manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fraenkel, L., Lim, J., Garcia-Tsao, G. et al. Variation in Treatment Priorities for Chronic Hepatitis C: A Latent Class Analysis. Patient 9, 241–249 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-015-0147-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-015-0147-7