Abstract

Background

Fatigue is one of the most common symptoms of major depressive disorder (MDD). The Fatigue Associated with Depression Questionnaire (FAsD) was developed to assess fatigue and its impact in patients with MDD. The current article presents the qualitative research conducted to develop and examine the content validity of the FAsD and FASD–Version 2 (FAsD–V2).

Methods

Three phases of qualitative research were conducted with patients recruited from a geographically diverse range of clinics in the US. Phase I included concept elicitation focus groups, followed by cognitive interviews. Phase II employed similar techniques in a more targeted sample. Phase III included cognitive interviews to examine whether minor edits made after Phase II altered comprehensibility of the instrument. Concept elicitation focused on patients’ perceptions of fatigue and its impact. Cognitive interviews focused on comprehension, clarity, relevance, and comprehensiveness of the instrument. Data were collected using semi-structured discussion guides. Thematic analyses were conducted and saturation was examined.

Results

A total of 98 patients with MDD were included. Patients’ statements during concept elicitation in phases I and II supported item development and content. Cognitive interviews supported the relevance of the instrument in the target population, and patients consistently demonstrated a good understanding of the instructions, items, response options, and recall period. Minor changes to instructions for the FAsD–V2 did not affect interpretation of the instrument.

Conclusions

This qualitative research supports the content validity of the FAsD and FAsD–V2. These results add to previous quantitative psychometric analysis suggesting the FAsD–V2 is a useful tool for assessing fatigue and its impact in patients with MDD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Residual symptoms of major depressive disorder (MDD) are associated with increased risk of relapse and impaired functioning. |

Fatigue is one of the most common symptoms of depression, and it often persists after other symptoms have remitted. |

The Fatigue Associated with Depression Questionnaire–Version 2 (FAsD–V2) was developed specifically to measure fatigue and its impact in patients with MDD. |

Items of the FAsD–V2 were developed and refined based on qualitative research with patients. This qualitative research is described in the current paper. |

The current qualitative results and previously published quantitative results suggest that the FAsD–V2 is a valid measure of fatigue and its impact in patients with MDD. |

1 Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a heterogeneous condition diagnosed based on a range of possible symptoms [1]. In recent years, research on depression has focused on a symptom-specific approach to treatment, often targeting residual symptoms that persist after other symptoms have responded to treatment [2–7]. Residual symptoms are an important target for research and treatment because they are predictive of relapse [7–12] and they contribute to psychosocial and occupational impairment after other symptoms have resolved [9, 13–17].

One depressive symptom that has been the focus of a growing body of research is fatigue [18–23]. Fatigue is one of the most common symptoms of MDD [24–27], and it has been shown to be a residual symptom that may persist in approximately 20–38 % of patients who have remitted [14, 28, 29]. Furthermore, fatigue may interfere with occupational functioning more than other depressive symptoms [30, 31]. Because fatigue is a common symptom with potential lasting serious impact, there is growing interest in its treatment and assessment [23]. Fatigue is typically included as an item in most patient-reported or clinician-rated measures of depression [32–35], and there are more detailed measures of fatigue developed for use in other patient populations [36, 37]. However, no previous measure of fatigue and its impact was developed specifically for patients with MDD.

Therefore, the Fatigue Associated with Depression Questionnaire (FAsD) was developed to assess fatigue and its impact among patients with depression [38]. This patient-reported outcome (PRO) measure allows for a brief yet detailed assessment of this important symptom. In a previously published psychometric validation study, the FAsD demonstrated good factor structure, internal consistency reliability, test–retest reliability, construct validity, and responsiveness to change [38, 39]. Prior to and concurrent with this quantitative evaluation of the FAsD, a series of qualitative studies was conducted to inform the development of the FAsD and examine its content validity. Content validity is the extent to which an instrument contains the relevant and important aspects of the concept it intends to measure, and it is established primarily through qualitative research with the target population [40–43].

While the first phase of qualitative research on the FAsD has been briefly described [38], phases II and III have not been previously published or presented. The purpose of the current article is to present the qualitative research conducted to develop the FAsD and ultimately the FAsD–V2, which is presented here for the first time. This research provides support for the FAsD–V2 as well as insight into fatigue and its impact among patients with depression.

2 Methods

2.1 Overview: Three Phases of Qualitative Research

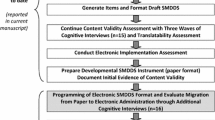

The three phases of qualitative research are summarized in Fig. 1. Phase I, which was conducted to support the development of the FAsD, began with four concept elicitation focus groups designed to identify key aspects of fatigue and its impact among patients with depression (N = 20). Qualitative information gathered during these focus groups was used to generate the initial set of items for the FAsD. These focus groups were followed by cognitive interviews with 18 additional patients, focused on evaluation of the draft FAsD. The instrument was edited based on patients’ comments, and this version was evaluated in a psychometric study [38]. Patient recruitment criteria for phase I did not specify inclusion/exclusion criteria related to racial/ethnic background or comorbidities. As a result, the phase I sample had a somewhat high proportion of Caucasian participants (Table 1), as well as some participants with comorbid conditions that could contribute to fatigue.

Phase II was conducted to examine the content validity of the FAsD in a more targeted sample. A more ethnically diverse sample was recruited from clinics in different geographic locations (Fig. 1; Table 1). In addition, participant exclusion criteria included a list of medical and psychiatric comorbidities that could contribute to fatigue. These criteria helped ensure that participants’ perceived depression-related fatigue was not actually caused by another condition. Phase II included a total of 44 patients who participated in five focus groups (N = 31) and 13 individual interviews. As in phase I, the focus groups were designed to elicit concepts related to fatigue and its impact. The individual interviews began with concept elicitation, followed by administration of the FAsD and a cognitive interview focused on clarity, comprehensiveness, and relevance of the instrument. All focus groups and cognitive interviews were facilitated by research staff trained in qualitative interviewing.

Based on discussions with regulatory authorities after completing phases I and II, the instructions of the FAsD were edited, resulting in Version 2 of the instrument (FAsD–V2). Phase III included 16 patients and focused on content validity of the FAsD–V2. The goal of phase III was to examine whether the minor edits to the instructions changed respondents’ interpretations of the instrument.

2.2 Participants

All participants were required to be (1) diagnosed with MDD, (2) at least 18 years of age, and (3) able to read and understand English. In phases II and III, participants were also required to have symptoms of depression, as indicated by a score of ≥5 on the 8-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-8) [44], to confirm that current self-reported symptoms were consistent with diagnoses of depression that appeared in medical charts. Potential participants were excluded if they reported (1) comorbid psychiatric conditions such as bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, or anxiety disorders; (2) medical conditions that might contribute to fatigue such as chronic fatigue syndrome, sleep apnea, cancer, multiple sclerosis, arthritis, and heart disease; or (3) that they were currently taking medication that could contribute to fatigue, such as mood stabilizers, antipsychotics, anxiolytics, or sleep aids.

With the exception of the phase I cognitive interviews, all participants were recruited from a geographically diverse range of clinical sites in the US (for locations, see Fig. 1). Sites were identified on CenterWatch (www.centerwatch.com), as well as based on the study team’s experiences conducting previous research on depression. Site staff identified potential study participants by reviewing patient medical charts and databases, as well as speaking to patients during regular clinic appointments. For the phase I cognitive interviews, participants were recruited via newspaper advertisements. All groups and interviews were held at the clinical site or at a nearby interview facility. All potentially eligible participants were screened using a standardized screening script. Demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1.

2.3 Measures

2.3.1 The Fatigue Associated with Depression Questionnaire (FAsD)

The FAsD was developed to assess fatigue and its impact in patients with MDD. The instrument was drafted based on literature review, patient focus groups, interviews with ten full-time clinicians who regularly treat depression (seven psychiatrists and three psychologists), and interviews with four clinical experts in depression (three psychiatrists and one psychologist). The instrument was then refined via cognitive interviews with patients [38]. The FAsD has demonstrated good factor structure, reliability, validity, and responsiveness to change [38, 39]. The FAsD includes a 6-item Fatigue Experience subscale and a 7-item Fatigue Impact subscale, and all items are answered on 5-point Likert scales with a recall period of 1 week. The scoring algorithm and recommendations for handling missing data have been published previously [38]. To assist with interpretation of change scores, responder definitions have been identified for the FAsD total score and subscales [39].

2.3.2 The FaSD–Version 2 (FAsD–V2)

Following discussions with regulatory authorities, the instructions of the FAsD were edited, resulting in Version 2 (Appendix A). Only two edits were made. First, the following material was deleted from the experience subscale instructions: “Some people experience fatigue when they are depressed. The following items ask you to rate fatigue you have experienced that you think may be related to depression”. Second, the following was deleted from the impact subscale instructions: “Now think about the impact of this fatigue that is related to depression”. These changes were made so that patients were not asked to attribute their fatigue specifically to depression. No changes were made to the items, recall period, response options, or scoring of the FAsD.

2.4 Data Collection: Two Qualitative Methods

This qualitative research followed standard methods used to support PRO measure development for use in clinical trials, including concept elicitation and cognitive interviews [40, 45, 46]. For concept elicitation, interviews or focus groups are conducted with individuals from the target patient population to inform the content of an instrument [41]. To identify content of the FAsD, phase I concept elicitation was performed in focus groups and replicated in phase II focus groups and individual interviews. All concept elicitation focus groups and interviews were conducted using semi-structured discussion/interview guides to facilitate and standardize the discussions. These guides were developed based on literature review and interviews with clinicians who specialize in treating depression. They were designed to elicit patients’ perceptions of their fatigue and its impact, as well as language used to describe these concepts so that the patients’ language could be incorporated into the FAsD. The discussion guides began by asking participants to briefly describe their depression symptoms, thus allowing for spontaneous report of fatigue. After symptoms were spontaneously reported during this introductory discussion, the remainder of the guide focused specifically on eliciting patient descriptions of fatigue experience and impact.

After drafting an instrument, the second step of qualitative research is to conduct cognitive interviews to assess and refine the draft instrument based on patients’ perceptions [42, 47]. Cognitive interviews in phases I and II focused on the first version of the FAsD, whereas the interviews in phase III focused on FAsD–V2. The purpose of these interviews was to confirm the content validity of the FAsD items while evaluating the instrument in terms of ease of use, clarity, comprehensibility, comprehensiveness, possible redundancy, and relevance to patients with depression. Interviews were conducted according to a structured interview guide that focused on evaluating patients’ understanding of the instructions, questions, response options, and recall period. For example, participants were instructed to describe how they understood the instrument’s instructions, how they interpreted each item, and how they selected a response.

All methods and materials were approved by an Independent Review Board [Ethical and Independent Review Services (E&I), which was known as the Ethical Review Committee at the time this study was initiated; protocol numbers A2-6535, A2-9866/10701, and A-10701], and all patients provided written informed consent to the interviewer or focus group moderator prior to completing any study measures or procedures. Focus groups and interviews were audio recorded and transcribed so that the qualitative data could be coded and analyzed.

2.5 Qualitative Data Analysis

A qualitative analysis software program, ATLAS.ti, was used to analyze the focus group and interview transcripts. This software allows for systematic assessment of the concepts and themes discussed by patients. For the qualitative analysis, a coding dictionary of themes, concepts, and terms was developed. For concept elicitation transcripts, the coding dictionary included concepts relating to fatigue and its impact. For cognitive interviews, the dictionary included codes related to comprehension of each item, as well as recall period, response options, and instructions.

In each of the three study phases, two trained staff members coded (i.e. labeled and categorized patients’ statements) the transcripts, and a senior project leader reviewed the codes and coordinated the coders’ efforts. For coding each set of transcripts, two coders began by independently coding the same transcript. The two coders then met with the project leader to compare and reconcile codes. Coding differences were discussed, and when agreement between the two coders was sufficient, the remaining transcripts were coded. Coders for phase II were new to the project team and blind to the transcripts, codes, and results of phase I qualitative research.

Participant quotes were categorized by thematic code, and saturation was documented (e.g. see phase II saturation grids in Tables 2 and 3). Saturation is defined as the point at which no substantially new themes, concepts, or terms are introduced as additional focus groups or interviews are conducted [46].

3 Results

3.1 Phase I: Development of the FAsD

A total of 20 patients participated in four concept elicitation focus groups (Table 1). Patients provided detailed descriptions of fatigue, including ‘tired’, ‘effort’, ‘slowed down’, lack of ‘motivation’, lack of ‘energy’, ‘exhausted’, ‘wiped out’, ‘drained’, ‘heavy’, ‘weak’, and ‘paralyzing’. All terms included in the FAsD were spontaneously reported by focus group participants. Some of these terms arose spontaneously during the detailed discussion of fatigue, while other terms such as ‘fatigue’ itself, were mentioned by participants during the introductory discussion of depression symptoms before the moderator introduced the topic of fatigue. Participants also described substantial impact of fatigue on multiple areas of their lives, including work/productivity, social activities, relationships with significant others (including sexual activity), and activities of daily living. No new important concepts or themes emerged in the third or fourth focus groups. Therefore, it was determined that saturation was reached after the second focus group, and these four focus groups were considered sufficient for eliciting concepts related to fatigue associated with depression. The concepts and terms identified in these focus groups were used when drafting the FAsD, which ensured that the content of the FAsD was grounded in patients’ perceptions and descriptions of fatigue.

The FAsD was drafted based on results of the four focus groups, as well as literature review and clinician interviews. This preliminary FAsD was then administered to 18 patients with depression who participated in cognitive interviews. All participants reported that the preliminary FAsD was clear and relevant to their condition. Suggestions for changes to the instrument were minor. Only one item, which asked about ‘weakness’, was unclear to a substantial number of participants (n = 7). Because other participants said this item was relevant, it was not dropped from the instrument, but it was clarified as ‘physically weak’.

The cognitive interviews also included questions about response options and recall period. Response options for Fatigue Experience items are presented as a 5-point Likert-type frequency scale because most participants talked about fatigue symptoms in terms of frequency rather than severity (e.g. how often they felt tired). Fatigue Impact items were worded in terms of severity for clarity and ease of reading (i.e. how severe was the impact). In the cognitive interviewing study, no concerns were reported by participants regarding these response options. A 1-week recall period was selected to limit a recall bias that may occur with longer recall periods, while providing a sufficient duration to capture the experience and impact of fatigue. While some participants in cognitive interviews indicated that they would prefer a longer recall period, the majority indicated that a 1-week period was appropriate. Therefore, the 1-week recall period was retained.

In response to patients’ comments in the cognitive interviews, minor edits were made to the instrument, yielding a 16-item draft of the FAsD to be administered in the subsequent psychometric validation study, which has been described elsewhere [38, 39]. Item reduction was performed in this validation study, resulting in the 13-item version of the FAsD that was published [38] and administered in the phase II cognitive interviews described below.

3.2 Phase II: Content Validity of the FAsD in a More Targeted Sample

The phase II sample was more diverse than the phase I sample in terms of racial/ethnic background (Table 1). Unlike the phase I sample, the phase II sample was also subject to exclusion criteria stating that potential patients were not eligible if they had psychiatric comorbidities, medical conditions, or current pharmaceutical treatment that could contribute to fatigue. Of the 44 patients in phase II (i.e. 31 in focus groups plus 13 interviews), 42 (95.5 %) met these strict inclusion/exclusion criteria. The other two participants met criteria based on their responses at screening but then reported medical conditions after completing their focus group participation (one patient reported polycystic fibrosis and another reported both asthma and hypothyroidism). Because of the difficulty removing qualitative data from individual participants in a focus group, data from these two participants were included along with the 42 participants who met the strict criteria.

Concept elicitation results in phase II were similar to the results of phase I, yielding similar descriptions of fatigue and its impact. In the five phase II focus groups, patients reported the same fatigue experiences and impact as the patients in phase I (see saturation grids in Tables 2 and 3). Phase II patients spontaneously described the concepts represented by every item of the FAsD without prompting from the moderators or interviewers. When asked in an open-ended way to describe fatigue and its impact, participants mentioned every concept that is included in the 13 items of the FAsD, often using the same language as the FAsD items. For example, in the first focus group, participants mentioned language from every FAsD item except the two items assessing impact on household chores and impact on school functioning. Then, in the second group, participants spontaneously raised household chores, and participants in the third group raised school functioning. Thus, every concept included in the FAsD was spontaneously reported by the third focus group. All FAsD concepts were also spontaneously reported by patients in the 13 individual interviews. Concept saturation was achieved by the fourth focus group and the ninth individual interview.

Phase II did not reveal any new fatigue-related concepts that did not arise in the original qualitative work. Of the terms mentioned in phase II, but not included in the FAsD, many describe the same underlying construct as existing items in the FAsD (e.g. a participant used ‘drained’ to describe ‘exhaustion’). Some other terms, such as ‘overwhelmed’, ‘melancholy’, and ‘aches and pains’, are likely to be linked to depression but describe concepts that are distinct from fatigue. Additional terms such as ‘motionless’, ‘stressless’, ‘funk’, and ‘dying slow’ are too idiomatic or vague for an instrument designed to be completed by a wide range of patients.

As with concept elicitation, the 13 phase II cognitive interviews also yielded similar results to the phase I cognitive interviews. Participants reported that the FAsD instructions, item language, and recall period were clear and easy to understand. All participants said the differences between the five experience and impact response options were comprehensible and in the correct order. It was evident the participants understood the 13 FAsD items as intended, based on their descriptions of the items and their response choices. All participants considered their current circumstances, both personally and professionally, when interpreting the impact items.

3.3 Phase III: Content Validity of the FAsD–V2

Following two minor edits to the instructions of the FAsD (described in the Methods section), a cognitive interview study was conducted to examine the content validity of the revised instrument, referred to as the FAsD–V2. All 16 participants said the briefer FAsD–V2 instructions were clear and easy to understand, similar to previous findings for the original FAsD. No participants suggested altering the wording or layout of the instructions. Furthermore, all participants were able to read and interpret the FAsD–V2 instructions and complete the FAsD–V2 items correctly.

It was evident that participants understood the FAsD–V2 items as intended, based on their descriptions of the items. For example, when asked how they interpreted the item assessing the impact of fatigue on daily household chores, participants described ‘daily household chores’ as including ‘cooking’, ‘cleaning’, ‘sweeping’, ‘taking the trash out’, ‘laundry’, and ‘shopping for groceries’. All patients were able to provide a clear rationale for the response option they selected, suggesting that they understood the item when completing the instrument. Similar results were found for the other items. Overall, patients demonstrated a good understanding of the items, recall period, and response options of the FAsD–V2, suggesting that the edits to the instructions did not have an impact on participants’ comprehension of the instrument.

4 Discussion

Overall, the results from phases I, II, and III of qualitative research with 98 patients strongly support the content validity of the FAsD. In concept elicitation with 64 patients in phases I and II, patients with depression reported detailed descriptions of fatigue and its impact, and similar descriptions of fatigue experience and impact spontaneously emerged in both phases. For example, in phase II, participants spontaneously reported all concepts that were included in the 13 items of the FAsD, which were drafted based on the phase I focus groups. Furthermore, no new fatigue-related concepts were introduced in the later focus groups. Therefore, these data strongly suggest that saturation has been reached, and no new fatigue-related concepts are likely to emerge from additional qualitative research.

Across the three phases of qualitative research, cognitive interviews were conducted with 47 patients from a diverse range of geographical and ethnic/racial backgrounds. These participants consistently reported that the FAsD instructions, items, recall period, and response options were clear and comprehensible. These patients’ descriptions of the FAsD questions and their response choices reflected a good understanding of the items. Participants also reported that the instrument was relevant to their experiences with depression. Like the concept elicitation work, the cognitive interviews support the content validity of the FAsD–V2.

The development of the FAsD provides an example of how early interaction with regulatory bodies is increasingly playing a role in PRO instrument development. The FAsD was developed in accordance with recommendations in the draft and final PRO guidance documents issued by the US FDA [40, 48]. Because it was hoped that FAsD data may eventually be used to support pharmaceutical labeling claims, the FAsD was discussed with representatives from the FDA. The original FAsD instructions asked patients to rate fatigue specifically attributed to depression. The FDA questioned whether patients would truly know the source of this fatigue, and it was suggested that the attributional language be removed. The instrument developers agreed that this deletion was reasonable because the purpose of the FAsD is to assess fatigue and its impact among patients with depression, rather than patients’ beliefs about the source of this fatigue. Therefore, these minor edits to the instructions were made, resulting in the FAsD–V2 (Appendix A), which was examined in the phase III cognitive interviews. In these interviews, all participants were able to correctly interpret the FAsD–V2 instructions, and it was evident the participants comprehended the FAsD–V2 items as intended, based on their descriptions of the items and their responses. These results suggested that the minor edits to the instructions had no impact on comprehensibility or content validity of the FAsD–V2. Furthermore, because no changes were made to the items, recall period, response options, or scoring, the psychometric analysis supporting the original FAsD can be considered applicable to version 2 [38, 39]. In light of this experience, future researchers developing PRO measures for use in the regulatory context may want to avoid the use of attributional language.

One limitation of this research is that qualitative methods cannot definitively determine the optimal recall period for a PRO measure. A 1-week recall period was selected for the FAsD–V2 for several reasons. First, the 1-week recall period is commonly used to assess depression symptoms in psychiatric clinical research, as with the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression [32], Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale [49], Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology [34, 50], and Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale [33]. The 1-week recall period maximizes comparability between the FAsD–V2 and these other depression measures that are often used in clinical trials. Second, in the current series of qualitative studies, the great majority of patients preferred 1-week over any other recall period, and patients consistently believed they could accurately report fatigue over this timeframe. Third, weekly recall was selected instead of a shorter recall period because the FAsD–V2 is intended to assess change in patients’ perceptions of their overall fatigue and its impact, rather than brief fluctuations in fatigue. Still, these findings should be interpreted with caution because patients may not be aware of their own memory limitations. It could be argued that a shorter recall period, such as 24 hours, could yield more accurate data with less memory-related bias than a 1-week recall period. There is a growing body of research comparing various recall periods, and these studies do not consistently support one recall period over another [51–57]. Therefore, recall periods for PRO measures need to be selected based on the content, patient population, and purpose of each individual instrument. Future research may help identify advantages and disadvantages of various recall periods for patient reports of depression symptoms.

5 Conclusions

Results from this series of qualitative studies add to previously published quantitative psychometric data [38, 39] and suggest that the FAsD–V2 is a useful and valid instrument for assessment of fatigue and its impact in patients with depression. More broadly, findings highlight the importance of fatigue as a target of clinical intervention. The descriptions of fatigue spontaneously reported by patients provide a rich picture of the fatigue experienced by patients with depression. Furthermore, patients consistently reported that fatigue has a substantial impact on multiple domains of their lives, including occupational functioning, social functioning, and self-care. Because fatigue is often a residual symptom, it may continue to have this impact even after other symptoms of depression have remitted with treatment. Therefore, depression-related fatigue is an important area of future research, and the FAsD–V2 is a useful tool for evaluating and quantifying this symptom.

References

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Arlington: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

Fava M. Pharmacological approaches to the treatment of residual symptoms. J Psychopharmacol. 2006;20(3 Suppl):29–34.

Han C, et al. Management of chronic depressive patients with residual symptoms. CNS Drugs. 2013;27(Suppl 1):S53–7.

Israel JA. The impact of residual symptoms in major depression. Pharmaceuticals. 2010;3:2426–40.

Kennedy SH. Core symptoms of major depressive disorder: relevance to diagnosis and treatment. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2008;10(3):271–7.

Kurian BT, Greer TL, Trivedi MH. Strategies to enhance the therapeutic efficacy of antidepressants: targeting residual symptoms. Expert Rev Neurother. 2009;9(7):975–84.

Menza M, Marin H, Opper RS. Residual symptoms in depression: can treatment be symptom-specific? J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(5):516–23.

Judd LL, et al. Major depressive disorder: a prospective study of residual subthreshold depressive symptoms as predictor of rapid relapse. J Affect Disord. 1998;50(2–3):97–108.

Judd LL, et al. Psychosocial disability during the long-term course of unipolar major depressive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57(4):375–80.

Mintz J, et al. Treatments of depression and the functional capacity to work. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49(10):761–8.

Thase ME, et al. Relapse after cognitive behavior therapy of depression: potential implications for longer courses of treatment. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149(8):1046–52.

Zajecka J, Kornstein SG, Blier P. Residual symptoms in major depressive disorder: prevalence, effects, and management. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(4):407–14.

Kennedy N, Paykel ES. Residual symptoms at remission from depression: impact on long-term outcome. J Affect Disord. 2004;80(2–3):135–44.

Nierenberg AA, et al. Residual symptoms after remission of major depressive disorder with citalopram and risk of relapse: a STAR*D report. Psychol Med. 2010;40(1):41–50.

Ogrodniczuk JS, Piper WE, Joyce AS. Residual symptoms in depressed patients who successfully respond to short-term psychotherapy. J Affect Disord. 2004;82(3):469–73.

Paykel ES. Remission and residual symptomatology in major depression. Psychopathology. 1998;31(1):5–14.

Romera I, et al. Residual symptoms and functioning in depression, does the type of residual symptom matter? A post-hoc analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:51.

Arnold LM. Understanding fatigue in major depressive disorder and other medical disorders. Psychosomatics. 2008;49(3):185–90.

Demyttenaere K, De Fruyt J, Stahl SM. The many faces of fatigue in major depressive disorder. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2005;8(1):93–105.

Fava M. Symptoms of fatigue and cognitive/executive dysfunction in major depressive disorder before and after antidepressant treatment. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(Suppl 14):30–4.

Pae CU, et al. Fatigue as a core symptom in major depressive disorder: overview and the role of bupropion. Expert Rev Neurother. 2007;7(10):1251–63.

Papakostas GI, et al. Resolution of sleepiness and fatigue in major depressive disorder: a comparison of bupropion and the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60(12):1350–5.

Targum SD, Fava M. Fatigue as a residual symptom of depression. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2011;8(10):40–3.

Marcus SM, et al. Gender differences in depression: findings from the STAR*D study. J Affect Disord. 2005;87(2–3):141–50.

Maurice-Tison S, et al. How to improve recognition and diagnosis of depressive syndromes using international diagnostic criteria. Br J Gen Pract. 1998;48(430):1245–6.

Moayedoddin B, et al. Prevalence and clinical characteristics of the DSM IV major depression among general internal medicine patients. Eur J Intern Med. 2013;24(8):763–6.

Tylee A, et al. DEPRES II (Depression Research in European Society II): a patient survey of the symptoms, disability and current management of depression in the community. DEPRES Steering Committee. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999;14(3):139–51.

Barkham M, et al. Dose-effect relations in time-limited psychotherapy for depression. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996;64(5):927–35.

Nierenberg AA, et al. Residual symptoms in depressed patients who respond acutely to fluoxetine. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(4):221–5.

Lam RW, et al. Which depressive symptoms and medication side effects are perceived by patients as interfering most with occupational functioning? Depress Res Treat. 2012;2012:630206.

Swindle R, Kroenke K, Braun L. Energy and improved workplace productivity in depression. In: Swindle R, Kroenka K, Braun L, editors. Investing in health: the social and economic benefits of health care innovation. Research in Human Capital and Development. Emerald Group Publishing Limited; 2001. p. 323–341.

Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62.

Montgomery SA, Åsberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry. 1979;134:382–9.

Rush AJ, et al. The inventory for depressive symptomatology (IDS): preliminary findings. Psychiatry Res. 1986;18(1):65–87.

Rush AJ, et al. The 16-item quick inventory of depressive symptomatology (QIDS), clinician rating (QIDS-C), and self-report (QIDS-SR): a psychometric evaluation in patients with chronic major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54(5):573–83.

Chalder T, et al. Development of a fatigue scale. J Psychosom Res. 1993;37(2):147–53.

Mendoza TR, et al. The rapid assessment of fatigue severity in cancer patients: use of the brief fatigue inventory. Cancer. 1999;85(5):1186–96.

Matza LS, et al. Development and validation of a patient-report measure of fatigue associated with depression. J Affect Disord. 2011;134(1–3):294–303.

Matza LS, et al. The Fatigue Associated with Depression Questionnaire (FAsD): responsiveness and responder definition. Qual Life Res. 2013;22(2):351–60.

US FDA. Guidance for industry. Patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims. Silver Spring: US FDA; 2009.

Patrick DL, et al. Content validity: establishing and reporting the evidence in newly developed patient-reported outcomes (PRO) instruments for medical product evaluation: ISPOR PRO good research practices task force report. Part 1: eliciting concepts for a new PRO instrument. Value Health. 2011;14(8):967–77.

Patrick DL, et al. Content validity: establishing and reporting the evidence in newly developed patient-reported outcomes (PRO) instruments for medical product evaluation: ISPOR PRO good research practices task force report. Part 2: assessing respondent understanding. Value Health. 2011;14(8):978–88.

Rothman M, et al. Use of existing patient-reported outcome (PRO) instruments and their modification: the ISPOR good research practices for evaluating and documenting content validity for the use of existing instruments and their modification PRO task force report. Value Health. 2009;12(8):1075–83.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL. The PHQ-9: A new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatric Annals. 2002;32(9):1–7.

Brod M, Tesler LE, Christensen TL. Qualitative research and content validity: developing best practices based on science and experience. Qual Life Res. 2009;18(9):1263–78.

Leidy NK, Vernon M. Perspectives on patient-reported outcomes: content validity and qualitative research in a changing clinical trial environment. Pharmacoeconomics. 2008;26(5):363–70.

Collins D. Pretesting survey instruments: an overview of cognitive methods. Qual Life Res. 2003;12(3):229–38.

US FDA. Guidance for industry. Patient reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims. Silver Spring: US FDA; 2006.

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361–70.

Rush AJ, et al. The inventory of depressive symptomatology (IDS): psychometric properties. Psychol Med. 1996;26(3):477–86.

Broderick JE, et al. The accuracy of pain and fatigue items across different reporting periods. Pain. 2008;139(1):146–57.

Lai JS, et al. Classical test theory and item response theory/Rasch model to assess differences between patient-reported fatigue using 7-day and 4-week recall periods. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(9):991–7.

McGorry RW, et al. Accuracy of pain recall in chronic and recurrent low back pain. J Occup Rehabil. 1999;9(3):169–78.

Schneider S, et al. Temporal trends in symptom experience predict the accuracy of recall PROs. J Psychosom Res. 2013;75(2):160–6.

Shi Q, et al. Does recall period have an effect on cancer patients’ ratings of the severity of multiple symptoms? J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;40(2):191–9.

Stone AA, Broderick JE, Kaell AT. Single momentary assessments are not reliable outcomes for clinical trials. Contemp Clin Trials. 2010;31(5):466–72.

Stone AA, Broderick JE, Schwartz JE. Validity of average, minimum, and maximum end-of-day recall assessments of pain and fatigue. Contemp Clin Trials. 2010;31(5):483–90.

Acknowledgments

Ellen B. Dennehy, Elizabeth N. Bush, and Thomas J. Konechnik are employees and minor shareholders in Eli Lilly and Company. Lindsey Murray, Louis Matza, and Dennis Revecki are employees of Evidera, formally known as UBC, which received funding from Eli Lilly and Company. Glenn Phillips previously worked for, and is a minor shareholder in, Eli Lilly and Company. The authors acknowledge the contributions of Peter Classi, MS, for his previous work with the FAsD. The authors would also like to thank Jessica Jordan for qualitative coding and review of the manuscript, as well as Amara Tiebout for production assistance. Funding for time spent on data collection and qualitative coding was provided by Eli Lilly & Co.; however, no funding was provided for time spent writing this manuscript.

Author contribution

Conception and design: Louis S. Matza, Lindsey Murray, Glenn A. Phillips, Thomas J. Konechnik, and Dennis A. Revicki. Acquisition of data: Louis S. Matza, Lindsey Murray, and Ellen B. Dennehy. Drafting of the manuscript: Louis S. Matza, Lindsey Murray, Ellen B. Dennehy, and Elizabeth N. Bush. Statistical analysis: Louis S. Matza, and Lindsey Murray. Obtaining funding: Glenn A. Phillips, and Ellen B. Dennehy. Administrative, technical, or material support: Louis S. Matza, Lindsey Murray, Ellen B. Dennehy, and Elizabeth N. Bush. Supervision: Glenn A. Phillips, and Dennis A. Revicki. Other: Louis S. Matza. All authors contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data, as well as critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Louis S. Matza is the guarantor for the overall content of this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix A

Appendix A

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Matza, L.S., Murray, L.T., Phillips, G.A. et al. Qualitative Research on Fatigue Associated with Depression: Content Validity of the Fatigue Associated with Depression Questionnaire (FAsD-V2). Patient 8, 433–443 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-014-0107-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-014-0107-7