Abstract

Psoriasis and atopic dermatitis are common, chronic inflammatory skin diseases. We discuss several aspects of these disorders, including: risk factors; incidence and prevalence; the complex disease burden; and the comorbidities that increase the clinical significance of each disorder. We also focus on treatment management strategies and outline why individualized, patient-centered treatment regimens should be part of the care plans for patients with either psoriasis or atopic dermatitis. Finally, we conclude that, while our theoretical knowledge of the optimum care plans for these patients is increasingly sophisticated, this understanding is, unfortunately, not always reflected in daily clinical practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Psoriasis: Affects More than Just Skin and Joints

Introduction

Psoriasis is a heterogeneous chronic inflammatory disease mediated by the immune system, which can affect the skin, nails, and joints [1, 2]. Psoriasis usually presents as red, scaling plaques on the scalp, lower back, and extensor aspects of the elbows and knees. Pustular psoriasis refers to two types: palmoplantar pustulosis, which forms painful pustules on the palms and/or soles; and generalized pustulosis, which is a serious disorder that appears as sterile pustules anywhere on the body [3].

Risk Factors

There is evidence that psoriasis may be hereditary, arising via complex interplay between multiple genes [4, 5]. Linkage analyses suggest that susceptibility to psoriasis is associated with genes that control inflammatory immune mechanisms, the cell cycle, and skin barrier function [5,6,7].

The histologic features of psoriasis—epidermal hyperplasia and altered keratinocyte differentiation—result from innate and adaptive immune response dysregulation [8]. Cells and molecules implicated in these immune responses, particularly activated T cells and dendritic cells, mediate the development of psoriasis [8, 9]. The inflammatory pathways implicated include the interleukin (IL)-23/IL-17 and nuclear factor-κB pathways [8, 10], while T-helper (Th) 1 and Th22 cells are also involved [8].

Environmental factors can trigger or exacerbate outbreaks of psoriasis in genetically predisposed individuals, including: weight gain, smoking, alcohol consumption, stress, withdrawal of corticosteroids, HIV infection, and the use of medications such as lithium, beta-blockers, or antimalarial agents [1, 7]. Various microorganisms have also been implicated in the pathogenesis of psoriasis, including fungi and viruses [11], although the strongest link has been provided for streptococcal infections [12]. Furthermore, obesity and psoriasis have overlapping genetic predispositions and interacting immune functions [13].

Incidence and Prevalence

According to a systematic review of population-based studies, the incidence of psoriasis varies according to age and geographic region, with a greater frequency in countries more distant from the equator [1]. The prevalence of psoriasis varies from 0% (Taiwan) to 2.1% (Italy) in children, and from 0.9% (United States) to 8.5% (Norway) in adults. While psoriasis appears to occur more frequently in women than men aged ≤18 years, the overall incidence between sexes is equal in adults. In a US study spanning 30 years, the incidence of psoriasis increased in adults over time, from 50.8/100,000 person-years between 1970 and 1974 to 100.5/100,000 person-years between 1995 and 1999 [1].

The Global Psoriasis Atlas, an international, population-based cohort study, will examine trends in incidence, prevalence, and mortality among patients with psoriasis over a 15-year period [14]. This study will help to address the need for more global, longitudinal studies providing such data.

Clinical Significance of Psoriasis

Physical Comorbidities

Psoriasis has been linked with a range of physical comorbidities [15] including: psoriatic arthritis; cardiovascular disease; Crohn’s disease; chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; sleep disorders; kidney disease; metabolic syndrome; and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease [16,17,18,19,20,21,22].

Psychosocial and Psychiatric Comorbidities

Risk factors for a variety of psychosocial and psychiatric comorbidities appear to be higher among patients with psoriasis compared with the general population [22]. For example, individuals may become secluded—prompting depression—when psoriatic lesions appear, thus treatment may promote an improvement in mood partly because of an improvement in psychodynamic issues [23]. Additionally, stress can exacerbate psoriasis, which itself is a stress-inducing disease [24].

Medications used to treat comorbidities may also exacerbate psoriasis in patients, potentially leading to depression, anxiety, and low self-esteem [15, 23,24,25]. Management of psoriasis should, therefore, incorporate a strategy to address both physical and non-physical comorbidities [24].

Burden of Psoriasis

The burden of psoriasis spans physical, psychologic, and social aspects. At present, psoriasis is an incurable disease that is often diagnosed before patients are aged 30 years. Consequently, individuals may live most of their adult life with a chronic, debilitating, and potentially stigmatizing illness [26], which may not always be acknowledged by clinicians [27].

Moderate-to-severe psoriasis may lead to an estimated 14 days of work absenteeism per year (26 days for severe psoriasis) compared with an average of 4.4 days in the general population [28]. One study, which assessed work absenteeism and reduced productivity, estimated that the psoriasis-associated loss to the UK economy was approximately £1.07 billion per year, although the actual loss is likely to be higher due to comorbid mental health issues and early retirement through ill health. Prompt referral of patients with psoriasis to specialist care, and multidisciplinary management of psoriasis alongside any comorbid disorders is, therefore, recommended [28].

Management of Psoriasis

Psoriasis-management decisions should be based on an assessment of the severity of disease, the presence of comorbidities, the need for referral to specialist care, and—where possible—identification of psoriasis trigger factors (Fig. 1) [29,30,31]. A US national survey of 1657 patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis found that almost 40% were not receiving treatment at the time, while around 25% of those with severe psoriasis received systemic therapy, phototherapy, or both; and 35% received topical medications alone [32]. The Multinational Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (MAPP) survey was initiated to gain a greater understanding of the real-world impact of psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, and treatment on patients’ daily lives [33]. This survey corroborated the results of the earlier study: moderate-to-severe psoriasis is under-treated with unmet needs throughout screening, assessment, and diagnosis (particularly in the case of psoriatic arthritis) [34]. Over recent years, a new generation of biologic treatments for psoriasis has emerged, including monoclonal antibodies targeting tumor necrosis factor-α (infliximab, adalimumab, and etanercept), IL-12/IL-23 (ustekinumab), and IL-17 (secukinumab and ixekizumab) [35, 36].

Flow diagram highlighting the key decision-making points and options available for clinicians when assessing patients with psoriasis [30]. For patients with mild-to-moderate psoriasis, topical treatment is regarded as being sufficient, with the addition of ultraviolet (UV) light in the case of an inadequate response. Moderate-to-severe disease requires management with systemic therapy, such as cyclosporin [29, 30]. However, cyclosporin has been associated with kidney damage, as well as an increased risk of non-melanoma skin cancer during UV light treatment, and, therefore, long-term therapy is not recommended [30, 31]. Similarly, methotrexate has been linked to hepatotoxicity in patients with psoriasis and diabetes and/or obesity [30]. Biologic agents, such as tumor necrosis factor-α antagonists, may be necessary for patients with psoriatic arthritis who require rapid and effective disease control [30]. Biologic agents are associated with higher treatment costs than other medications, while their use is linked to the development of harmful anti-drug antibodies and their efficacy may be reduced in obese patients [30]. (Ref. [30], copyright 2014, reproduced with permission of Blackwell)

General Outcome Measures

Changes in general well-being may be an important indicator of a patient’s response to psoriasis treatment. One of the most commonly used outcome measures for assessing the impact of psoriasis on quality of life is the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI [37, 38]). Another widely used quality-of-life measure is the European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D™) questionnaire [39], which has been validated in psoriasis [40]. The Short Form (36) Health Survey (SF-36) is another non-disease-specific measure of health status, which has shown validity in psoriasis [40, 41]. These surveys provide useful assessments of general physical functioning, including mobility and pain; and psychosocial functioning, including depression.

Disease-Specific Outcome Measures

The most widely used psoriasis-specific survey is the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI), which quantifies the extent of the disease and provides an accurate assessment of treatment efficacy [42]. The PASI provides a composite index of the three main signs of psoriatic plaques (erythema, scaling, and thickness) weighted according to the affected regions of the body. Another measure of disease severity is the body surface area (BSA), which categorizes psoriasis as mild, moderate, or severe according to the proportion of the body that is affected [43].

Recurrence of lesions after treatment discontinuation is a common occurrence in psoriasis. There is evidence to support the concept that the expression of some psoriasis-associated genes in healed lesional skin remains abnormal after treatment [44]. Gaining an understanding of the processes involved and continuing to treat these “invisible” lesions may pave the way to achieve true resolution of disease.

Atopic Dermatitis

Introduction

Atopic dermatitis often begins in childhood, preceding the development of food allergy or asthma, and is characterized by intense itching and recurrent eczematous lesions [45, 46]. While a defective epidermal barrier is common to all patients with atopic dermatitis, it presents as a highly variable disease [46,47,48].

Risk Factors

The pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis is not fully understood: skin barrier defects driven by a combination of genetic and environmental factors, and immune dysregulation have been implicated [45, 49]. The variability in clinical presentation may be a consequence of the differing activation of polar immune axes. Cytokine production differs between patients with intrinsic (non-allergic) and extrinsic (allergic) atopic dermatitis [45].

The triggers of atopic dermatitis include diet, allergen exposure, stress, and irritants. Environmental factors that could trigger atopic dermatitis include colonization or infection of the skin with microbes, such as Staphylococcus aureus or the Herpes simplex virus. Such infections would usually trigger keratinocytes to produce antimicrobial peptides and initiate an immune response; however, keratinocytes from the skin of patients with atopic dermatitis are deficient in their ability to produce antimicrobial peptides [45]. In addition, the gut microbiome may be a factor, with gut bacterial depletion and altered metabolic activity at the age of 3 months being implicated in childhood atopy and asthma [50].

Incidence and Prevalence

Atopic dermatitis is the most common chronic inflammatory skin disease. The prevalence of the disease in Western countries has increased over the past 30 years, and approximately 15–20% of children and 1–3% of adults may be affected [48, 51]. Although it is commonly perceived as being primarily a childhood disease, atopic dermatitis may persist through to adulthood in up to 50% of cases. Furthermore, “late-onset” (at age 40 years+) and “very late-onset” (at age 60 years+) atopic dermatitis is increasingly being diagnosed [45].

Clinical Significance of Atopic Dermatitis

Physical Comorbidities

Atopic dermatitis is often accompanied by allergic rhinitis, asthma, and food allergy (the “atopic march”), as well as conjunctivitis [49, 52]. The prevalence of asthma among children with atopic dermatitis ranges from 14.2 to 52.7%, while 75% of children with severe atopic dermatitis develop allergic rhinitis [52]. The incidence of food allergies among those with atopic dermatitis appears to be more common than in the general population, but obtaining exact figures is hampered by varying definitions adopted across studies [52].

Psychiatric Comorbidities and Burden of Disease

An association has been found between an increased severity of atopic dermatitis and a greater frequency of psychologic disturbances, including anxiety, depression, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, autism, and suicidal ideation [52]. This supports the need to effectively manage the disease in order to improve the general well-being and quality of life of patients and their families [53, 54]. For example, parents of children with atopic dermatitis may be affected because of the time-consuming nature of implementing treatment regimens or dietary and household changes. Also, atopic dermatitis can have a substantial financial impact on both individual families and society (with US societal estimates ranging from <$100 to >$2000 per patient per year) [55].

Optimal management of atopic dermatitis requires a full appreciation of the breadth of the burden that it imparts. Targeting parents and caregivers with educational and psychosocial support can help to alleviate this burden, with improved medical, psychosocial, and family outcomes having the potential to decrease the associated financial costs [55]. Scoring Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD) is a composite index that was developed as a means of quantifying the extent, severity, and subjective symptoms of atopic dermatitis as an indicator of its clinical burden [56].

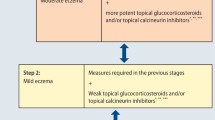

Management of Atopic Dermatitis

For the past several years, the topical application of corticosteroids and calcineurin inhibitors (e.g., tacrolimus and pimecrolimus) has represented the mainstay of anti-inflammatory therapy for atopic dermatitis [57]. However, since atopic dermatitis is such a varied disorder, there is an argument to stratify patients into distinguishable endotypes and phenotypes to better inform treatment decisions. Successful management of atopic dermatitis incorporates skin hydration, skin barrier repair, topical anti-inflammatory medications (e.g., corticosteroids), control of infection, and elimination of exacerbating factors. As there are no cures for food allergy or asthma, effective treatments for atopic dermatitis may be important for preventing the natural course of the “atopic march” [45].

Different treatment approaches may be appropriate for patients with extrinsic and intrinsic disease, as only extrinsic atopic dermatitis is associated with high levels of serum immunoglobulin E. The pathogenesis of both is largely driven by T cells, and treatment with cyclosporin, which suppresses T-cell activation, can be successful [58]. However, the differential expression of other immune molecules, such as IL-17, IL-22, and IL-23/IL-12p40, may be significant for the differential treatment of extrinsic and intrinsic atopic dermatitis [58].

Two recent studies have shown that neonates at high risk for atopic dermatitis can be prevented from developing the disease through the application of emollients from birth, which improves skin hydration and reduces skin permeability to allergens, thereby potentially correcting the subclinical dysfunction of the skin barrier and controlling the inflammatory process [59, 60]. Further studies may show whether this approach could reduce the incidence of food allergies as part of the “atopic march” [59, 60].

The skin microbiome is believed to be correlated with atopic dermatitis [61]. Staphylococcus aureus infections may predispose a patient to disseminated viral skin infections, which may be critical to outcomes in small children with atopic dermatitis [62].

There are conflicting reports on the importance of diet in the management of atopic dermatitis [63]. Low-level evidence suggests that the use of probiotics by pregnant and nursing mothers, or infants, reduces the risk of atopic dermatitis in infants [64]. In children likely to have vitamin D deficiency during the winter months, vitamin D supplementation has been shown to produce a clinically and statistically significant improvement in winter-related atopic dermatitis [65].

Future Treatment Options

Patients with atopic dermatitis often require systemic, immunomodulating, and immunosuppressive therapy, but the use of such regimens can be hampered by toxicity and inadequate response [66]. Interferon-γ induces heightened immune surveillance and immune system function during infection [67]. Treatment with recombinant interferon-γ is well-tolerated in patients with severe, unremitting atopic dermatitis, with clinical improvement reflecting decreases in absolute white blood cell and eosinophil counts [68]. This type of therapy shows particular promise among pediatric patients with atopic dermatitis, although further studies are needed to determine the effects of interferon-γ on the prevalence of skin infection [69].

Several cytokines have been implicated in atopic allergic disease [70, 71]. Treatment with the fully human immunoglobulin-G1 monoclonal antibody ustekinumab, which binds to IL-12 and IL-23 and prevents upregulation of IL-17-producing T cells, was associated with marked clinical improvement in a patient with refractory atopic dermatitis [66]. This follows the successful use of ustekinumab in patients with psoriasis, which also involves IL-12 and IL-23 [72]. In addition, evidence has indicated that dupilumab, a monoclonal antibody targeting IL-4 receptor α, may lead to a rapid improvement in atopic dermatitis across almost all measures of disease activity, with relatively mild and non-dose-limiting side effects. This is, therefore, a promising therapy for all moderate-to-severe cases of atopic dermatitis, regardless of endotype or phenotype [73,74,75].

Another target for the potential treatment of atopic dermatitis is cyclic adenosine monophosphate phosphodiesterase, which is present at an abnormally high level in the leukocytes of patients with the disease [76]. Selective inhibition of phosphodiesterase with topical cipamfylline was efficacious in the treatment of atopic dermatitis, although results were inferior to those achieved with topical hydrocortisone [76]. Greater potential has been shown for the newer phosphodiesterase inhibitors, apremilast and topical AN2728, although few studies have been published and the long-term impact of treatment is unknown [77]. Future treatment options for atopic dermatitis have been reviewed in more detail elsewhere [78].

Patient-Centered Treatment Strategies for Psoriasis and Atopic Dermatitis

An individualized, patient-centered approach is essential for the effective management of psoriasis and atopic dermatitis, and their associated comorbidities (Fig. 2). Future directions for psoriasis and atopic dermatitis treatments may arise from more precise definitions of endotypes, which could facilitate tailored treatment plans. Such tailoring could mean that initiating treatment at an earlier age will help minimize or reduce comorbidities, thereby improving quality of life and reducing the detrimental impact on a patient’s home and work life. In addition, effective and appropriate education of patients and their family and/or support network is of prime importance.

Psoriasis and atopic dermatitis are chronic diseases that require patients to receive long-term treatment. While these disorders have a detrimental impact on many aspects of patients’ lives, patients may sometimes feel that this is not fully appreciated by their doctors. Crucially, good interpersonal communication between doctors and patients is the key to treatment success.

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not involve any new studies of human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

References

Parisi R, Symmons DP, Griffiths CE, Ashcroft DM. Global epidemiology of psoriasis: a systematic review of incidence and prevalence. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:377–85.

Weigle N, McBane S. Psoriasis. Am Fam Physician. 2013;87:626–33.

Psoriasis Association. Types of psoriasis. https://www.psoriasis-association.org.uk/pages/view/about-psoriasis/types-of-psoriasis. Accessed 3 May 2016.

Sundarrajan S, Arumugam M. Comorbidities of psoriasis – exploring the links by network approach. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0149175.

Wolf N, Quaranta M, Prescott NJ, et al. Psoriasis is associated with pleiotropic susceptibility loci identified in type II diabetes and Crohn disease. J Med Genet. 2008;45:114–6.

O’Rielly DD, Rahman P. Genetics of susceptibility and treatment response in psoriatic arthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2011;7:718–32.

Roberson ED, Bowcock AM. Psoriasis genetics: breaking the barrier. Trends Genet. 2010;26:415–23.

Sun L, Zhang X. The immunological and genetic aspects in psoriasis. Appl Inform. 2014;1:3.

Lowes MA, Suárez-Fariñas M, Krueger JG. Immunology of psoriasis. Annu Rev Immunol. 2014;32:227–55.

Nograles KE, Davidovici B, Krueger JG. New insights in the immunologic basis of psoriasis. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2010;29:3–9.

Fry L, Baker BS. Triggering psoriasis: the role of infections and medications. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:606–15.

Thorleifsdottir RH, Eysteinsdóttir JH, Olafsson JH, et al. Throat infections are associated with exacerbation in a substantial proportion of patients with chronic plaque psoriasis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2016;96:788–91.

Reich K. The concept of psoriasis as a systemic inflammation: implications for disease management. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26(Suppl 2):3–11.

International Federation of Psoriasis Associations. International Federation of Psoriasis Associations: WHO Global report on Psoriasis. http://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20160224005875/en/International-Federation-Psoriasis-Associations-Global-report-Psoriasis. Accessed 3 May 2016.

Gottlieb AB, Chao C, Dann F. Psoriasis comorbidities. J Dermatolog Treat. 2008;19:5–21.

Abedini R, Salehi M, Lajevardi V, Beygi S. Patients with psoriasis are at a higher risk of developing nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015;40:722–7.

Gisondi P, Targher G, Zoppini G, Girolomoni G. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in patients with chronic plaque psoriasis. J Hepatol. 2009;51:758–64.

Gupta R, Debbaneh MG, Liao W. Genetic epidemiology of psoriasis. Curr Dermatol Rep. 2014;3:61–78.

Ogdie A, Gelfand JM. Clinical risk factors for the development of psoriatic arthritis among patients with psoriasis: a review of available evidence. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2015;17:64.

Mansouri B, Kivelevitch D, Natarajan B, et al. Comparison of coronary artery calcium scores between patients with psoriasis and type 2 diabetes. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:1244–53.

Machado-Pinto J, Diniz Mdos S, Bavoso NC. Psoriasis: new comorbidities. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91:8–14.

Wu Y, Mills D, Bala M. Psoriasis: cardiovascular risk factors and other disease comorbidities. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:373–7.

Oliveira Mde F, Rocha Bde O, Duarte GV. Psoriasis: classical and emerging comorbidities. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:9–20.

Ferreira BI, Abreu JL, Reis JP, Figueiredo AM. Psoriasis and associated psychiatric disorders: a systematic review on etiopathogenesis and clinical correlation. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2016;9:36–43.

Frew JW. The clinical significance of drug interactions between dermatological and psychoactive medications. Dermatol Ther. 2014;27:1–11.

Cordingley L, Nelson PA, Griffiths CE, Chew-Graham CA. Beyond skin: the need for a new approach to the management of psoriasis in primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2012;62:568–9.

Nelson PA, Chew-Graham CA, Griffiths CE, Cordingley L. Recognition of need in health care consultations: a qualitative study of people with psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:354–61.

Bajorek Z, Hind A, Bevan S. The impact of long term conditions on employment and the wider UK economy. http://www.theworkfoundation.com/Reports/397/The-impact-of-long-term-conditions-on-employment-and-the-wider-UK-economy. Accessed 4 May 2016.

Murphy G, Reich K. In touch with psoriasis: topical treatments and current guidelines. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25(Suppl 4):3–8.

Mrowietz U, Steinz K, Gerdes S. Psoriasis: to treat or to manage? Exp Dermatol. 2014;23:705–9.

Beyaert R, Beaugerie L, Van Assche G, et al. Cancer risk in immune-mediated inflammatory diseases (IMID). Mol Cancer. 2013;12:98.

Horn EJ, Fox KM, Patel V, Chiou CF, Dann F, Lebwohl M. Are patients with psoriasis undertreated? Results of National Psoriasis Foundation survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:957–62.

van de Kerkhof PC, Reich K, Kavanaugh A, et al. Physician perspectives in the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: results from the population-based Multinational Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis survey. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:2002–10.

Lebwohl MG, Kavanaugh A, Armstrong AW, Van Voorhees AS. US perspectives in the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: patient and physician results from the population-based Multinational Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (MAPP) survey. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2016;17:87–97.

Nast A, Jacobs A, Rosumeck S, Werner RN. Efficacy and safety of systemic long-term treatments for moderate-to-severe psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:2641–8.

Gómez-Garcia F, Epstein D, Isla-Tejera B, Lorente A, Vélez García-Nieto A, Ruano J. Short-term efficacy and safety of new biologic agents targeting IL-23/Th17 pathway for moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2016. doi:10.1111/bjd.14814.

Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)–a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:210–6.

Basra MK, Fenech R, Gatt RM, Salek MS, Finlay AY. The Dermatology Life Quality Index 1994–2007: a comprehensive review of validation data and clinical results. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:997–1035.

EuroQol Group. EuroQol—a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16:199–208.

Shikiar R, Willian MK, Okun MM, Thompson CS, Revicki DA. The validity and responsiveness of three quality of life measures in the assessment of psoriasis patients: results of a phase II study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4:71.

Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–83.

Feldman SR, Fleischer AB Jr, Reboussin DM, et al. The self-administered psoriasis area and severity index is valid and reliable. J Invest Dermatol. 1996;106:183–6.

EPG Health Media (Europe) Ltd. Psoriasis Knowledge Centre. Diagnosis and Disease Assessment. http://www.epgonline.org/psoriasis-knowledge-centre/disease-awareness/diagnosis/. Accessed 4 May 2016.

Clark RA. Gone but not forgotten: lesional memory in psoriatic skin. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131:283–5.

Leung DY, Guttman-Yassky E. Deciphering the complexities of atopic dermatitis: shifting paradigms in treatment approaches. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:769–79.

Weidinger S, Novak N. Atopic dermatitis. Lancet. 2016;387:1109–22.

Deleuran M, Vestergaard C. Clinical heterogeneity and differential diagnosis of atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170(Suppl 1):2–6.

Nutten S. Atopic dermatitis: global epidemiology and risk factors. Ann Nutr Metab. 2015;66(Suppl 1):8–16.

Wananukul S, Chatproedprai S, Tempark T, Phuthongkamt W, Chatchatee P. The natural course of childhood atopic dermatitis: a retrospective cohort study. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2015;33:161–8.

Arrieta MC, Stiemsma LT, Dimitriu PA, et al. Early infancy microbial and metabolic alterations affect risk of childhood asthma. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7:307ra152.

Shaw TE, Currie GP, Koudelka CW, Simpson EL. Eczema prevalence in the United States: data from the 2003 National Survey of Children’s Health. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131:67–73.

Simpson EL. Comorbidity in atopic dermatitis. Curr Dermatol Rep. 2012;1:29–38.

Lifschitz C. The impact of atopic dermatitis on quality of life. Ann Nutr Metab. 2015;66(Suppl 1):34–40.

Drucker AM, Wang AR, Qureshi AA. Research gaps in quality of life and economic burden of atopic dermatitis: the National Eczema Association burden of disease audit. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:873–4.

Carroll CL, Balkrishnan R, Feldman SR, Fleischer AB Jr, Manuel JC. The burden of atopic dermatitis: impact on the patient, family, and society. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:192–9.

Stalder JF, Taïeb A (co-ordinators). Severity scoring of atopic dermatitis: the SCORAD index. Consensus report of the European Task Force on atopic dermatitis. Dermatology. 1993;186:23–31.

Ring J, Alomar A, Bieber T, et al. Guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) part I. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:1045–60.

Suårez-Fariñas M, Dhingra N, Gittler J, et al. Intrinsic atopic dermatitis shows similar TH2 and higher TH17 immune activation compared with extrinsic atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132:361–70.

Horimukai K, Morita K, Narita M, et al. Application of moisturizer to neonates prevents development of atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134(824–30):e6.

Simpson EL, Chalmers JR, Hanifin JM, et al. Emollient enhancement of the skin barrier from birth offers effective atopic dermatitis prevention. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:818–23.

Grice EA, Segre JA. The skin microbiome. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2011;9:244–53.

Bin L, Kim BE, Brauweiler A, et al. Staphylococcus aureus α-toxin modulates skin host response to viral infection. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130:683–91.

Bronsnick T, Murzaku EC, Rao BK. Diet in dermatology: Part I. Atopic dermatitis, acne, and nonmelanoma skin cancer. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:1039.e1–1039.e12.

Cuello-Garcia CA, Brozek JL, Fiocchi A, et al. Probiotics for the prevention of allergy: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136:952–61.

Camargo CA Jr, Ganmaa D, Sidbury R, Erdenedelger K, Radnaakhand N, Khandsuren B. Randomized trial of vitamin D supplementation for winter-related atopic dermatitis in children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134(831–5):e1.

Puya R, Alvarez-López M, Velez A, Casas Asuncion E, Moreno JC. Treatment of severe refractory adult atopic dermatitis with ustekinumab. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:115–6.

Ong PY, Leung DY. Bacterial and viral Infections in atopic dermatitis: a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2016;51:329–37.

Chang TT, Stevens SR. Atopic dermatitis: the role of recombinant interferon-gamma therapy. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2002;3:175–83.

Brar K, Leung DY. Recent considerations in the use of recombinant interferon gamma for biological therapy of atopic dermatitis. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2016;16:507–14.

Guilloteau K, Paris I, Pedretti N, et al. Skin inflammation induced by the synergistic action of IL-17A, IL-22, oncostatin M, IL-1α, and TNF-α recapitulates some features of psoriasis. J Immunol. 2010;184:5263–70.

Souwer Y, Szegedi K, Kapsenberg ML, de Jong EC. IL-17 and IL-22 in atopic allergic disease. Curr Opin Immunol. 2010;22:821–6.

Leonardi CL, Kimball AB, Papp KA, et al. Efficacy and safety of ustekinumab, a human interleukin-12/23 monoclonal antibody, in patients with psoriasis: 76-week results from a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (PHOENIX 1). Lancet. 2008;371:1665–74.

Nahm DH. Personalized immunomodulatory therapy for atopic dermatitis: an allergist’s view. Ann Dermatol. 2015;27:355–63.

Hamilton JD, Suarez-Farinas M, Dhingra N, et al. Dupilumab improves the molecular signature in skin of patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:1293–300.

Boyman O, Kaegi C, Akdis M, et al. EAACI IG Biologicals task force paper on the use of biologic agents in allergic disorders. Allergy. 2015;70:727–54.

Griffiths CE, Van Leent EJ, Gilbert M, Traulsen J. Randomized comparison of the type 4 phosphodiesterase inhibitor cipamfylline cream, cream vehicle and hydrocortisone 17-butyrate cream for the treatment of atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:299–307.

Moustafa F, Feldman SR. A review of phosphodiesterase-inhibition and the potential role for phosphodiesterase 4-inhibitors in clinical dermatology. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:22608.

Howell MD, Parker ML, Mustelin T, Ranade K. Past, present, and future for biologic intervention in atopic dermatitis. Allergy. 2015;70:887–96.

Acknowledgements

Sponsorship and article processing charges for this supplement were funded by Almirall S.A. This article is based on presentations from the 9th Skin Academy Symposium, April 9–10, 2016, Barcelona, Spain, sponsored by Almirall S.A. All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval to the version to be published. Medical writing support was provided by Chrissie Kouremenou of Complete Medical Communications, funded by Almirall S.A.

Disclosures

Christopher E. M. Griffiths has received honoraria and/or research funds from AbbVie, Actelion, Almirall S.A., Amgen, Celgene, Janssen, Leo Pharma, Lilly, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Sandoz, and UCB Pharma. Peter van de Kerkhof has participated in clinical trials, has been a consultant, and given lectures, for AbbVie, Almirall S.A., Amgen, Celgene, Centocor, Ely Lilly, Galderma, Janssen-Cilag, Leo Pharma, Mitsubishi, Novartis, Pfizer, Philips, and Sandoz. Magdalena Czarnecka-Operacz has been a consultant for Berlin-Chemie and Novartis, and a speaker for Allergopharma, Almirall S.A., Berlin-Chemie, Bioderma, Leo Pharma, Meda, Novartis, and Pierre-Fabre.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies, and does not involve any new studies of human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Data Availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced content

To view enhanced content for this article go to http://www.medengine.com/Redeem/6C47F0600685C21C.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Griffiths, C.E.M., van de Kerkhof, P. & Czarnecka-Operacz, M. Psoriasis and Atopic Dermatitis. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 7 (Suppl 1), 31–41 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-016-0167-9

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-016-0167-9