Abstract

Prognosis and appropriate treatment goals for older adults with diabetes vary greatly according to frailty. It is now recognised that changes may be needed to diabetes management in some older people. Whilst there is clear guidance on the evaluation of frailty and subsequent target setting for people living with frailty, there remains a lack of formal guidance for healthcare professionals in how to achieve these targets. The management of older adults with type 2 diabetes is complicated by comorbidities, shortened life expectancy and exaggerated consequences of adverse effects from treatment. In particular, older adults are more prone to hypoglycaemia and are more vulnerable to its consequences, including falls, fractures, hospitalisation, cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality. Thus, assessment of frailty should be a routine component of a diabetes review for all older adults, and glycaemic targets and therapeutic choices should be modified accordingly. Evidence suggests that over-treatment of older adults with type 2 diabetes is common, with many having had their regimens intensified over preceding years when they were in better health, or during more recent acute hospital admissions when their blood glucose levels might have been atypically high, and nutritional intake may vary. In addition, assistance in taking medications, as often occurs in later life following implementation of community care strategies or admittance to a care home, may dramatically improve treatment adherence, leading to a fall in glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) levels. As a person with diabetes gets older, simplification, switching or de-escalation of the therapeutic regimen may be necessary, depending on their level of frailty and HbA1c levels. Consideration should be given, in particular, to de-escalation of therapies that may induce hypoglycaemia, such as sulphonylureas and shorter-acting insulins. We discuss the use of available glucose-lowering therapies in older adults and recommend simple glycaemic management algorithms according to their level of frailty.

Similar content being viewed by others

Frailty, rather than age, determines the prognosis for older adults with diabetes, and should therefore be a key determinant of target setting and treatment choices when individualising care. |

Frailty-dependent glycaemic treatment targets and de-escalation thresholds have previously been described and are generally accepted. |

There is a lack of formal guidance for healthcare professionals on the best routes to achieve these targets. |

We summarise here the relative merits of various drug classes as they pertain to older adults with diabetes and recommend simple glycaemic management algorithms according to their level of frailty. |

Digital Features

This article is published with digital features, including a summary slide, to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.13953110.

Introduction

A recently published UK national collaborative stakeholder initiative [1] provides guidance on the assessment of frailty in older adults with type 2 diabetes, and on appropriate glucose target setting. Although the choice of medications was briefly mentioned, accumulating evidence, including analyses from large-scale cardiovascular outcomes trials (CVOTs), means that clearer guidance can now be provided on the relative benefits and potential risks of available treatment options in this population. This article builds upon our previous work [1] to discuss degrees of frailty in older adults with type 2 diabetes, and how treatment goals should vary accordingly. Our aim is to provide prescriptive guidance for glycaemic management in older adults with diabetes according to frailty, including frailty-specific glycaemic targets.

We believe that detailed advice is needed for healthcare professionals caring for older people with diabetes on how to safely prescribe newer glucose-lowering therapy and when to intensify or de-escalate treatment. Primary care teams often lack the confidence to make what may seem like radical changes to established therapeutic regimens; rather, maintaining the ‘status quo’ may feel ‘safer’. Furthermore, a pervading view is that type 2 diabetes is a progressive disease that requires continual escalation of treatment until a ‘final’ intensified regimen is arrived at. Increasing age and frailty status, however, ought to require that periodic reassessments are made of the treatment regimen. Changes, including the de-prescribing of certain elements or switching to newer and perhaps unfamiliar drugs, may be required and may be more beneficial to patient safety, adherence and care.

While valuable evidence-based guidance has been published on the overall management of people aged ≥ 65 years with diabetes [2, 3], and international guidance is available that addresses the overall management of frailty in older adults [4], there is limited formal and practical guidance, for primary care teams in particular, on how to vary type 2 diabetes therapy in older people according to their level of frailty. However, the importance of this is beginning to be addressed in recent publications [5, 6]. Historically, there has been a lack of routine assessment of frailty, functional status and comorbidities in clinical trials on diabetes, which has contributed largely to the insufficient characterization of older study participants [7].

The lack of clear guidance and pathways in complex patients is a recognised contributor to clinical inertia [8]. In order to overcome treatment inertia, we feel it is important to provide guidance on de-prescribing/de-escalation and to highlight the complications and comorbidities of type 2 diabetes in older adults that should be considered as part of a holistic and multifactorial management approach. Medical, psychological and functional issues, such as sarcopenia, heart failure, hypertension, lipid profile, urinary incontinence, cognitive decline, depression, diet, physical condition, falls and fractures, swallowing difficulties, an increased need for assistance with the administration of medication by carers or care home staff and polypharmacy can all impact upon adherence and the pharmacodynamic response to glucose-lowering therapies.

We hope that the information provided here (based on the literature and expert opinion) will be useful to primary care and community teams (general practitioners, practice nurses, nurse practitioners, community nurses etc.) as well as diabetologists working with older adults and geriatricians caring for people with diabetes. Our aim is to encourage appropriate revision of therapy according to individual need and frailty status.

This article is based on previous studies reported in the literature and on expert opinion. As such, it does not report results from studies performed by the authors with human participants or animals.

Degrees of Frailty and Treatment Goals in Older Adults with Type 2 Diabetes

Frailty has been described as “a condition characterised by loss of biological reserves across multiple organ systems and vulnerability to physiological decompensation after a stressor event” [9]. There are several ways to assess frailty, but tools like the electronic Frailty Index (eFI) [10], Rockwood scale [10] and Timed up and Go [11, 12] can be used to confirm clinical suspicion. The eFI makes use of existing electronic health records and uses a ‘cumulative deficit’ model to assess frailty on the basis of accumulation of up to 36 deficits, including clinical signs and symptoms such as tremor or problems with vision, diseases, disabilities or abnormal test values [10]. Other tools for measuring frailty in routine clinical practice are available and, in particular, the FRAIL scale, a 5-item questionnaire that has been validated in multiple populations [13], is increasingly being used, as it does not require a procedure and can be completed in several minutes.

Frailty is not a simple correlate of age, necessarily progressive nor irreversible [9]. Some older adults with diabetes have numerous diabetes-related comorbidities, limited cognitive or physical functioning and a severe degree of frailty, whereas others may have few or no comorbidities and be very active with only a mild degree of frailty.

Prognosis, and hence appropriate diabetes treatment goals, for older adults with diabetes vary greatly according to frailty, and therefore need to be individualised [14]. For example, older and more frail people with diabetes who have significant comorbidity or substantial cognitive or functional impairments are less likely to live long enough to reap the benefits of long-term intensive diabetes management, such as a reduced risk of vascular complications. They are also more likely to suffer serious adverse effects from hypoglycaemia. Indeed, a recent systematic review suggested that both low (< 42 mmol/mol; < 6%) and high (> 75 mmol/mol; > 9%) glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) levels were associated with more harm than benefit in older adults [14]. In this review, an HbA1c between 59 and 64 mmol/mol (7.5 and 8.0%) was associated with the most favourable outcomes. It is therefore reasonable to set less intensive glycaemic goals in these individuals, although it is important to clarify that the majority of studies that contributed to this systematic review were conducted before the widespread availability of agents that can achieve normoglycaemia with only a very small risk of hypoglycaemia. Improved diabetes control may thus be beneficial in some situations, yet de-escalating treatments that have an adverse side-effect profile may be beneficial in others. As a result, the 2019/20 General Medical Services (GMS) contract Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) [15] now recognises that frailty should be accounted for in the routine care of older people with diabetes and acknowledges that higher glycaemic targets may be appropriate in older adults living with frailty.

A further issue to consider when assessing HbA1c in older adults is the accuracy of the metric itself. There are multiple comorbidities that confound HbA1c values (Table 1). Any condition that increases red blood cell turnover, such as bleeding conditions (e.g. peptic ulcer disease) or haemolytic conditions (e.g. significant valvular disease), will artificially lower HbA1c values [16]. Conversely, for the majority of older adults who have reduced red blood cell turnover, increased cellular membrane friability and iron deficiency anaemia can result in an artificial elevation of the HbA1c value [17,18,19]. Even in healthy older adults eligible for inclusion in intensive glycaemic control trials, lower levels of fasting plasma glucose were found to be required to achieve a similar HbA1c [20].

Once established, apart from age and gender, frailty is the single biggest predictor of mortality in older adults [10]. As a result, frailty, rather than comorbidity, underpins target setting, recommended interventions and treatment goals in older adults with diabetes (Table 2). It is important to remember that frailty is a dynamic process; a person’s frailty categorisation may change, hence the need for regular reassessment, particularly following a change in circumstances, such as moving to a care home, hospitalisation, increased adherence to medications or weight loss due to decreased appetite. Re-evaluation of frailty should occur, as a minimum, at the annual diabetes review, but earlier if there has been a change in health status, and 3 months after any intervention (escalation or de-escalation). Targets may need to be re-evaluated based on the development and diagnosis of co-existing chronic illnesses and/or changes in cognitive function and functional status. Individuals should be assessed for any signs of change in physical or mental status, or in vision or cardiovascular (CV) status. Frailty may improve if either recurrent hypoglycaemia or profound hyperglycaemia are rectified [21].

Diet and Exercise

Frail older people with diabetes may also suffer from malnutrition or sarcopenia [22, 23]. Therefore, the management of diabetes in older people should also focus on diet and exercise [24]. Any resulting weight loss from lifestyle intervention in frail older people with diabetes or overweight should be modest (e.g. 5–7%) [24, 25]. Optimal nutrition with adequate protein intake is recommended for maintaining muscle volume in such patients [24]. However, it should be noted that there are potential disadvantages associated with high protein intake: for example, red meat intake may increase the risk of end-stage renal disease [26]. Therefore, maintaining a daily protein intake of 0.8 g protein/kg is recommended for both healthy individuals and those with diabetes and chronic kidney disease [27].

As it is now clear that the functional deficits associated with frailty in older adults with diabetes can be reversed [28], it is important that older adults with type 2 diabetes are encouraged to exercise regularly, if such activities can be carried out safely [24]. These exercises include weight-bearing activity, aerobic activity and/or resistance training [24]. Loss of skeletal muscle strength is accelerated in older adults with type 2 diabetes versus those without type 2 diabetes [29]. Mild exercise is likely to reduce muscle atrophy [30, 31] and improve quality of life (QoL).

Hypoglycaemia in Older Adults with Diabetes

Hypoglycaemic events can be distressing for people with diabetes at any age. Many learn to recognise the symptoms and self-manage impending events, but repeated exposure to hypoglycaemia can lead to impaired counter-regulation and ‘hypoglycaemia unawareness’, such that symptoms become attenuated and/or manifest only at very low glucose levels, rendering the person less able to respond [32]. Consequently, hypoglycaemia becomes increasingly problematic with age. Furthermore, in frail older adults, hypoglycaemic symptoms such as dizziness, confusion and visual disturbances, which often present more commonly than adrenergic symptoms (palpitations, sweating, tremors), can be mistaken for dementia or neurological problems [33, 34]. Indeed, vague nonspecific symptoms of confusion, loss of confidence, imbalance and falls, impaired sleep or nightmares and cognitive decline are all common in frail older adults with and without diabetes [35].

Older adults with type 2 diabetes are more prone to hypoglycaemia as a result of various factors, including polypharmacy [36, 37], endocrine deficits, suboptimal water and food intake and cognitive impairment, as well as cardiovascular disease (CVD) and renal dysfunction [34, 38, 39]. In addition to being at increased risk of hypoglycaemia, frail older adults are more vulnerable to its consequences. Hypoglycaemia in older people increases the risk of serious outcomes, such as falls, fractures, cognitive decline, hospitalisation, CV events (thought to involve cardiac conduction disturbances) and all-cause mortality [40]. In the landmark ACCORD trial, the risk of severe hypoglycaemia increased with age and, for participants reporting severe hypoglycaemia, mortality was increased threefold [41]. This study also showed a potential harm for people with type 2 diabetes and high CV risk who were treated intensively to achieve an ambitious glycaemic target [42], and this has led to guidelines relaxing recommended HbA1c targets for older adults. Additionally, the presence of comorbidities such as osteoporosis or of conditions requiring anticoagulation may further compound the effects of a fall resulting from a hypoglycaemic episode. Even mild hypoglycaemic events can be consequential for older people, since they can raise concerns about an individual’s driving competence, social isolation issues, self-care capacity, confidence and cognitive status, as well as impacting upon emotional wellbeing [21] [40].

It follows that the avoidance of hypoglycaemia must be a paramount concern in the diabetes management of the frail older adult, and it cannot be assumed that regimens previously well tolerated in this respect will remain so. The treatments for type 2 diabetes with the greatest propensity for causing hypoglycaemia are insulin and the insulin secretagogues: sulphonylureas (SUs) and glinides.

Review of Available Anti-hyperglycaemic Therapies

The pharmacological options for treating type 2 diabetes have increased greatly in recent years, and a comprehensive account is beyond the scope of this consensus report. For brevity, our consensus on the pros and cons of the various drug classes as they pertain to older adults are summarised in Table 3, and some further considerations are discussed below.

The two drug types with the longest history of use in type 2 diabetes are metformin and the SUs. Metformin is widely regarded as a well-tolerated drug and it is routinely used as first-line therapy, with other agents added over time, to maintain glycaemic control. It is contraindicated in severe renal failure and should be used with caution in those with impaired hepatic function or cardiac failure due to increased risk of lactic acidosis. It is important to remember that these situations arise and progress with age and that reduced renal function will lead to increased drug exposure. As such, assessment of estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) before treatment with metformin, and every 3–6 months thereafter, is recommended, with adjustments to the dose if necessary [43]. It is recommended that the total maximum daily dose of metformin in people with mildly to moderately decreased renal function (eGFR 45–59 mL/min/1.73 m2), which is 2000 mg, is halved once the eGFR drops to < 45 mL/min/1.73 m2 and that metformin is discontinued once the eGFR drops to < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 [43]. Metformin treatment is associated with reduced or maintained body weight, compared with weight gain for SUs [44].

SUs have had a more controversial history, with a well-documented hypoglycaemia risk as well as concerns over CV safety [45]. Recently published data from the CAROLINA CVOT were reassuring regarding CV risk [46], but the study did not include older frail adults. SUs vary in their duration of action and peak:trough ratios, and the shorter-acting second-generation SUs, such as gliclazide, carry a lower risk of hypoglycaemia than longer-acting SUs such as glyburide [45].

Thiazolidinediones (TZDs) are associated with a low risk of hypoglycaemia and, although not focussed on older adults, a meta-analysis of trials in participants with CVD found that pioglitazone lowered the risk of recurrent major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), stroke or myocardial infarction [47]. However, the risk of developing heart failure was increased [47]. Other concerns still surround the use of pioglitazone and the risk of bladder cancer [48], as well as a potential associated risk of osteoporosis and fractures [49,50,51], all of which are more frequent in older adults. Pioglitazone should therefore be used with caution in people with symptomatic heart disease or osteoporosis, and is contraindicated in those with a history of bladder cancer or active bladder cancer. Treatment with TZDs is associated with an increase in body weight [44].

Oral dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors (DPP-4is) have few side effects and are associated with a minimal risk of hypoglycaemia [52]. They have been formally evaluated in frail older adults, in whom they demonstrated an efficacy and safety profile similar to that seen in younger adults [53]. A recent meta-analysis of outcome data from completed CVOTs also suggested that, apart from saxagliptin, DPP-4is have a neutral effect on CV death, myocardial infarction, stroke and hospitalisation for heart failure [54]. However, their relatively high cost may be a barrier in some regions where medications have to be paid for directly. In terms of effect on body weight, DPP-4is have been shown to be weight-neutral or associated with reductions in body weight [44].

Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) may be safely initiated in primary care. Although they are given by subcutaneous (sc) injection, which requires sufficient visual, motor and cognitive skills for administration, there are once-weekly options [55], and a once-daily oral formulation of semaglutide is now available [56]. In a meta-analysis of older adults (> 65 years) eligible for enrolment in CVOTs, treatment with GLP-1 RAs was associated with a 15.2% reduction in MACE [57]. Of particular relevance to the older population, stroke, as a component of MACE, is significantly reduced by the use of GLP-1 RAs [58]. These benefits are manifested in months, rather than years, which may be especially relevant for the older frail adult, for whom life expectancy is more limited. There is also evidence that GLP-1 RAs have renoprotective effects [59]. Results of a meta-analysis found that treatment with GLP-1 RAs in adults with type 2 diabetes was associated with maintained or reduced body weight [44]. However, GLP-1 RAs may cause nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea, which could be problematic in frailer adults, in whom weight loss is a poor prognostic indicator. Similarly, their effect on appetite suppression, whilst being an advantage in younger populations, may be detrimental in the frail elderly patient. While GLP-1 RAs may be attractive choices in the healthy older adult, there is no evidence currently supporting their use in frail older adults.

Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT-2is), administered orally, are easy to initiate in primary care [60]. However, their glucose-lowering efficacy diminishes with declining renal function, which should be monitored regularly [61]. The benefit in MACE outcomes attributed to SGLT-2is is predominantly driven by their benefit in older adults. Indeed, a recent meta-analysis of outcome data from completed CVOTs stratified by age suggested that SGLT-2is reduced MACE outcomes in an older population by 16.9% whilst having no impact in younger populations [57]. Although the data were not specific to older adults, hospitalisations due to heart failure were also shown to be reduced (by 28%; p < 0.001) in a pooled analysis of three CVOTs with SGLT-2is [54]. Again, benefits manifested within months, particularly in heart failure, which may be especially relevant for the frail older adult. There is also evidence that SGLT-2is have renoprotective effects, slowing the progression of chronic kidney disease [59]. SGLT-2is cause weight loss through glucosuria and carry a risk of urinary incontinence [62]. In our clinical experience, the risk of candidiasis with SGLT-2is is also exaggerated in older adults. Finally, it should also be noted that the increased diuresis induced by SGLT-2is can lead to modest decreases in blood pressure that may be more pronounced in people with very high blood glucose concentrations, with a risk of hypotension and falls. While there is some evidence that SGLT-2is may be attractive choices in the healthy older adult, there is no evidence currently supporting their use in frail older adults.

Insulin was once considered a treatment of last resort in type 2 diabetes, but the availability of long-acting basal insulin analogues, such as insulin degludec or insulin glargine U300, with a relatively low risk of hypoglycaemia compared with earlier products and flexible dose timing [63], has led to increasing use at earlier stages of type 2 diabetes, with easier initiation by primary care teams. Nevertheless, a lot of fear can still surround the use of insulin in older adults, with uncertainties over balancing glycaemic control/stability with hypoglycaemia risk, and how and when to initiate. The use of a long-acting basal insulin with a higher target fasting plasma glucose, in the 7–12 mmol/L range, can accomplish adequate glycaemic control with a low risk of hypoglycaemia. Furthermore, the ultra-long acting insulins offer a greater flexibility for administration by a caregiver should the older person with diabetes not have sufficient visual and motor skills, and/or cognitive ability, to administer insulin on their own. Degludec and insulin glargine U300 have been shown to have durations of action of beyond 42 h and up to 36 h, respectively [64, 65]. Dosing of each may be once daily at any time of the day, and preferably at the same time every day. On occasions when administration at the same time of the day is not possible, degludec allows for flexibility in dose timing as long as a minimum of 8 h between injections is ensured [64]. Similarly, when needed, people with diabetes may administer glargine U300 up to 3 h before or after their usual time of administration [64]. Multiple daily injections may be too complex for older frail adults, whilst providing an unnecessary degree of tight glycaemic control, and low doses of once-daily basal insulin analogues may be a reasonable option in many.

Glycaemic Management in Older Adults with Diabetes, According to Frailty

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) provide detailed treatment algorithms for the management of diabetes in healthy adults. Based on the knowledge that disease-modifying agents such as GLP-1 RAs and SGLT-2is have a similar benefit in older adults eligible to participate in the large, multinational, randomised controlled trials, we suggest that fit older adults aged < 75 years should follow an algorithm based on the ADA/EASD consensus statement [52]. The only potential exception is that of the use of TZDs for the management of diabetes in patients for whom hypoglycaemia should be avoided; this class of oral antihyperglycaemic drugs is relegated to a reserve position due to their impact on osteoporosis and risk of heart failure.

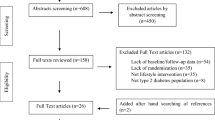

In line with the section of the ADA/EASD guidelines, however, we believe that the choice of agents for the management of diabetes in older adults should be based on frailty status and the extent of co-existing chronic illness and cognitive and functional status [6, 52, 66]. We recommend following the simple glycaemic management algorithm depicted in Fig. 1 for older adults with type 2 diabetes, according to their level of frailty.

Treatment escalation and simplification/de-escalation plan for older adults living with type 2 diabetes and with no or mild frailty (a), moderate frailty (b) or severe frailty (c). Moderate frailty is defined as individuals with > 2 comorbidities, some impairments in activities of daily living with a reduced life expectancy. Severe frailty comprises significant comorbidity, functional deficits and limited independence; i.e. conditions likely to cause a markedly reduced life expectancy. Severe frailty guidelines are largely ‘evidence-free’ and represent stakeholders’ recommendations. Patients may already be receiving treatment with metformin, SUs or their combination plus or minus basal or premix insulin. †At time of publication, treatment with any SGLT-2i can be initiated at eGFR > 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 for the management of hyperglycaemia: canagliflozin can be initiated at > 45 mL/min/1.73 m2 or > 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 in people with proteinuria; dapagliflozin can be initiated at any HbA1c for the management of heart failure. All SGLT-2is are less efficacious at reducing hyperglycaemia at lower eGFRs. ‡Expert recommendation. ASCVD Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, BNP B-type natriuretic peptide, degludec insulin degludec, DPP-4i dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor, eGFR estimated glomerular filtration rate, FPG fasting plasma glucose, GLP-1 RA glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist, HbA1c glycated haemoglobin, HF heart failure, IDegLira fixed-ratio combination of insulin degludec and liraglutide, IGlar U300 insulin glargine 300 units/mL, LixiLan fixed-ratio combination of insulin glargine and lixisenatide, NPH neutral protamine Hagedorn, SU sulphonylurea, SGLT-2i sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitor, TZD thiazolidinedione

Individuals may already be receiving treatment with metformin, SUs or their combination plus or minus basal or premix insulin. In some cases, discontinuation of certain drugs is advocated, but with suitable replacements suggested. When escalating therapy, the risk of hypoglycaemia should be considered for those on insulin or SUs. It is not necessary to automatically discontinue an SU if there is no evidence of hypoglycaemia, although the dose should be reduced in the short term. For people on neutral protamine Hagedorn (NPH) or premix insulin, switching to a basal insulin analogue (glargine, detemir, or degludec) with a DPP-4i can be considered.

Treatment Simplification/De-escalation Guidance in the Glycaemic Management of Older Adults with Diabetes

As a person with diabetes gets older, simplification, switching or de-escalation of the therapeutic regimen may be necessary, depending on the level of frailty and HbA1c levels. When contemplating modification of a diabetes regimen, it is helpful to conduct a basic audit of the status of the person with diabetes. An individual at advanced age (e.g. ≥ 75 years), identified as being moderately or severely frail, with an HbA1c value < 53 mmol/mol (< 7.0%) would suggest a high risk of occurrence of complications from hypoglycaemia. Consideration should be given to de-escalation of therapies that may induce this feared complication, such as SUs or SU + insulin combinations. A recent assessment of > 190,000 people with type 2 diabetes found that, while mean HbA1c was suboptimal in younger adults, it was approximately 52 mmol/mol (6.9%) in those aged ≥ 75 years [67]. HbA1c also tended to be lower in adults with advanced comorbidities, and the use of SUs increased with age, likely the legacy of a longer duration of disease and/or treatment. Furthermore, a recent cohort study of older people with type 2 diabetes found that those in poorer health were most likely to be using insulin at age 75 years, with subsequent discontinuation more common in healthier older adults [68]. These findings suggest that over-treatment of older adults is common, perhaps unintentionally, as a result of legacy regimens that have now become too potent as frailty has increased. There will, however, also be individuals whose QoL is impacted upon unintentionally by a too lax glycaemic control.

Many frail older adults with type 2 diabetes will have had their regimens intensified over preceding years when they were in better health, and many others will have had their regimens intensified or been started on SUs or insulin more recently during acute hospital admissions (e.g. for infections), when their blood glucose levels might have been atypically high. In addition, in older frail adults who start to receive assistance in taking their medications, either following admittance to a care home or in another setting, treatment adherence that may previously have been poor can suddenly improve dramatically, leading to a fall in HbA1c levels. It should not be assumed that treatment regimens that have been intensified historically or those that were initiated in hospitals should continue indefinitely. In the latter case, a return to pre-admission medications may be needed to avoid hypoglycaemia, although, in the case of longstanding symptomatic poor control, the escalated regimen may be appropriate if it is tolerated and the older adult is not severely frail. Primary care teams therefore need to consider each person with diabetes individually, but they should feel empowered to de-escalate a discharge regimen if appropriate. Evidence suggests that simplification, reduction or even complete withdrawal of hypoglycaemic medications in older people with diabetes is feasible without deterioration of glycaemic control [69]. As frailty ensues, older adults lose adipose tissue, which, in turn, reduces underlying insulin resistance. As a result, much smaller doses of insulin are often sufficient to provide adequate and reproducible glycaemic control.

For older adults with diabetes, attending medical appointments may be difficult or impractical. In such cases, teleconsultations may be a suitable alternative [70,71,72]. Remote blood glucose monitoring linked to web-based cloud technologies allows for the transfer of continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) data directly to healthcare professionals (e.g. intermittent CGM) [73, 74]. However, the suitability of these telemedicine activities for the individual should be carefully considered, as they may not be effective in all cases [71, 75].

Older adults with diabetes who have inadequate glycaemic control or recurrent hypoglycaemia on their current treatment regimen, who have had a significant change in circumstances, such as a move into a care home, or who are no longer be able to manage complex insulin therapy (may also apply to those with mild frailty whose cognitive or functional ability declines) may benefit from regimen simplification or de-escalation. We recommend following the simple algorithm depicted in Fig. 1 for treatment simplification/de-escalation in the glycaemic management of older adults with type 2 diabetes. De-escalation of non-insulin glucose-lowering regimens can be achieved by either lowering the dose or discontinuing some medications. Insulin regimens can either be de-escalated by reduction of the dose or simplified by switching to more manageable regimens with lower risk of hypoglycaemia such as, for example, from premix insulins to a basal insulin analogue with or without a GLP-1 RA or SGLT-2i [76, 77]. Glucose monitoring in older adults with type 2 diabetes should be increased after any switch in insulin therapy, with the dosages adjusted on an individual basis and dependent on the previous insulin regimen [64, 65]. It is important to be mindful that SUs and GLP-1 RAs raise endogenous insulin secretion, hence they decrease the unit-dose requirement for exogenous insulin compared with insulin monotherapy. A sensible approach would be either to reduce the dose of SU when administered in combination with insulin or to discontinue SU treatment altogether, in favour of insulin monotherapy with close metabolic monitoring during and after any change in regimen. TZDs also increase sensitivity to insulin, so, again, compensatory dose adjustments are required when these are used in combination with insulin. In a small proportion of individuals, stopping insulin suddenly can precipitate diabetic ketoacidosis, so insulin should be withdrawn slowly and response to each dose adjustment should be monitored, ideally within 1 month. A single early-morning urinary C-peptide to creatinine ratio measurement [78] can provide reassurance that there is sufficient residual pancreatic function to safely de-escalate and discontinue insulin, but this may have to be organised by secondary care teams for people living in the community.

Often during reviews of frail older adults, individuals will be identified with a low HbA1c (< 48 mmol/mol; < 6.5%). It should be considered that insulin resistance may have subsided sufficiently that no therapies are required. In this scenario, it is reasonable to discontinue all antihyperglycaemic agents and review control after 3 months against an individualised HbA1c goal. Anti-hyperglycaemic therapies can work in synergy, hence the removal of one (even low-dose) component of a regimen can result in a dramatic rise in HbA1c (rebound hyperglycaemia). This highlights the importance of monitoring HbA1c and reviewing the individual if medication is de-escalated. Care must be taken to identify those who may be at risk of rebound hyperglycaemia if on multiple agents even if HbA1c is < 48 mmol/mol (< 6.5%) and, therefore, in such circumstances, a pragmatic/sequential cessation of medication may be required. In such people, previous glycaemic control/HbA1c and medication commencement history may support rapid or slower discontinuation. HbA1c can rise sharply after stopping an SU, even if this has been taken for many years, so it may be appropriate to restart at a lower dose in such cases.

People living with diabetes should be reviewed after each change in regimen (i.e. a 3-month review programme with an HbA1c measurement after every withdrawal) to check that glycaemic control (and other risk factor management) is appropriate for their frailty category, and also to check whether frailty status has changed. In all cases, it is important to explain to the individual (and relatives) that the reasons for de-escalation are concerned with improving symptoms, function and QoL, frailty status and comorbidity in order to avoid the misconception that de-escalation represents ‘giving up hope’.

Whilst focus is made on de-escalation and avoidance of hypoglycaemia, it is equally important to remember that complex regimens and multiple medications will contribute to pill burden and polypharmacy, which can have a significant impact on the individual (who may already be on multiple other medications, given associations with comorbidities). Therefore, a regular review of medication is recommended, and considerations should be made for simplification of regimens, where possible, to reduce pill burden, including consideration of combination therapies. This may also improve overall adherence to medication regimens, not just those for the treatment of diabetes, and help reduce both the cost of treatment and medication errors.

Summary and Conclusions

The management of older adults with type 2 diabetes is complicated by comorbidities, shortened life expectancy and exaggerated consequences of adverse effects from treatment, such as hypoglycaemia. The assessment of frailty should be a routine component of a diabetes review for all older adults, and then glycaemic targets and therapeutic choices should be modified accordingly. After each intervention, frailty should be reassessed, cognisant of the fact that frailty is a dynamic process and may be improved by the elimination of both hyper- and hypoglycaemia.

References

Strain WD, Hope SV, Green A, Kar P, Valabhji J, Sinclair AJ. Type 2 diabetes mellitus in older people: a brief statement of key principles of modern day management including the assessment of frailty. A national collaborative stakeholder initiative. Diabet Med. 2018;35:838–45.

International Diabetes Federation. Global guideline for managing older people with type 2 diabetes. 2013. https://www.idf.org/e-library/guidelines/78-global-guideline-for-managing-older-people-with-type-2-diabetes.html. Accessed 14 Oct 2020.

LeRoith D, Biessels GJ, Braithwaite SS, et al. Treatment of diabetes in older adults: an Endocrine Society* clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endo Metab. 2019;104:1520–74.

Sinclair AJ, Abdelhafiz A, Dunning T, et al. An international position statement on the management of frailty in diabetes mellitus: summary of recommendations 2017. J Frailty Aging. 2018;7:10–20.

Hambling CE, Khunti K, Cos X, et al. Factors influencing safe glucose-lowering in older adults with type 2 diabetes: a PeRsOn-centred ApproaCh To IndiVidualisEd (PROACTIVE) Glycemic Goals for older people: a position statement of Primary Care Diabetes Europe. Prim Care Diabetes. 2019;13:330–52.

American Diabetes Association. 12. Older adults: standards of medical care in diabetes—2020. Diabetes Care. 2020;43:S152–S62.

Sinclair AJ, Heller SR, Pratley RE, et al. Evaluating glucose-lowering treatment in older people with diabetes: lessons from the IMPERIUM trial. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2020;22:1231–42.

Strain WD, Blüher M, Paldánius P. Clinical inertia in individualising care for diabetes: is there time to do more in type 2 diabetes? Diabetes Ther. 2014;5:347–54.

Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, Rikkert MO, Rockwood K. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet. 2013;381:752–62.

Clegg A, Bates C, Young J, et al. Development and validation of an electronic frailty index using routine primary care electronic health record data. Age Ageing. 2016;45:353–60.

Podsiadlo D, Richardson S. The timed “Up & Go”: a test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39:142–8.

Nordin E, Rosendahl E, Lundin-Olsson L. Timed, “Up & Go” test: reliability in older people dependent in activities of daily living—focus on cognitive state. Phys Ther. 2006;86:646–55.

Morley JE, Malmstrom TK, Miller DK. A simple frailty questionnaire (FRAIL) predicts outcomes in middle aged African Americans. J Nutr Health Aging. 2012;16:601–8.

Sinclair AJ, Abdelhafiz AH, Forbes A, Munshi M. Evidence-based diabetes care for older people with type 2 diabetes: a critical review. Diabet Med. 2019;36:399–413.

NHS England. 2019/20 General Medical Services (GMS) contract quality and outcomes framework (QOF). Guidance for GMS contract 2019/20 in England. 2019. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/gms-contract-qof-guidance-april-2019.pdf. Accessed 14 Oct 2020.

Kiniwa N, Okumiya T, Tokuhiro S, Matsumura Y, Matsui H, Koga M. Hemolysis causes a decrease in HbA1c level but not in glycated albumin or 1,5-anhydroglucitol level. Scand J Clin Lab Investig. 2019;79:377–80.

English E, Idris I, Smith G, Dhatariya K, Kilpatrick ES, John WG. The effect of anaemia and abnormalities of erythrocyte indices on HbA1c analysis: a systematic review. Diabetologia. 2015;58:1409–21.

Guo W, Zhou Q, Jia Y, Xu J. Increased levels of glycated hemoglobin A1c and iron deficiency anemia: a review. Med Sci Monit. 2019;25:8371–8.

Ahmad J, Rafat D. HbA1c and iron deficiency: a review. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2013;7:118–22.

Heller SR, DeVries JH, Wysham C, Hansen CT, Hansen MV, Frier BM. Lower rates of hypoglycaemia in older individuals with type 2 diabetes using insulin degludec versus insulin glargine U100: results from SWITCH 2. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2019;21:1634–41.

McCluskey L, Jagger O, Strain WD. Hypoglycemia associated with impaired mobility and diminished confidence in an elderly person with type 2 diabetes. Diabet Hypoglycemia. 2014;7:11–4.

Liu GX, Chen Y, Yang YX, et al. Pilot study of the Mini Nutritional Assessment on predicting outcomes in older adults with type 2 diabetes. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2017;17:2485–92.

Sanz Paris A, Garcia JM, Gomez-Candela C, et al. Malnutrition prevalence in hospitalized elderly diabetic patients. Nutr Hosp. 2013;28:592–9.

American Diabetes Association. 12. Older adults: standards of medical care in diabetes—2021. Diabetes Care. 2021;44:S168–S79.

Franz MJ, Bantle JP, Beebe CA, et al. Nutrition principles and recommendations in diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(Suppl 1):S36-46.

Lew QJ, Jafar TH, Koh HW, et al. Red meat intake and risk of ESRD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28:304–12.

Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes Diabetes Work Group. KDIGO 2020 clinical practice guideline for diabetes management in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2020;2020(98):S1–115.

Rodriguez-Mañas L, Laosa O, Vellas B, et al. Effectiveness of a multimodal intervention in functionally impaired older people with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2019;10:721–33.

Park SW, Goodpaster BH, Strotmeyer ES, et al. Accelerated loss of skeletal muscle strength in older adults with type 2 diabetes: the health, aging, and body composition study. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:1507–12.

Kalyani RR, Corriere M, Ferrucci L. Age-related and disease-related muscle loss: the effect of diabetes, obesity, and other diseases. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2:819–29.

Cauza E, Strehblow C, Metz-Schimmerl S, et al. Effects of progressive strength training on muscle mass in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients determined by computed tomography. Wien Med Wochenschr. 2009;159:141–7.

Seaquist ER, Anderson J, Childs B, et al. Hypoglycemia and diabetes: a report of a workgroup of the American Diabetes Association and the Endocrine Society. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:1384–95.

Hope SV, Taylor PJ, Shields BM, Hattersley AT, Hamilton W. Are we missing hypoglycaemia? Elderly patients with insulin-treated diabetes present to primary care frequently with non-specific symptoms associated with hypoglycaemia. Prim Care Diabetes. 2018;12:139–46.

Freeman J. Management of hypoglycemia in older adults with type 2 diabetes. Postgrad Med. 2019;131:241–50.

Brož J, Urbanová J, Frier BM. Hypoglycemia in the elderly: watch for atypical symptoms. J Fam Pract. 2019;68:74.

Sinclair A, Dunning T, Rodriguez-Mañas L. Diabetes in older people: new insights and remaining challenges. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015;3:275–85.

Abdelhafiz AH, Rodriguez-Manas L, Morley JE, Sinclair AJ. Hypoglycemia in older people—a less well recognized risk factor for frailty. Aging Dis. 2015;6:156–67.

Pathak RD, Schroeder EB, Seaquist ER, et al. Severe hypoglycemia requiring medical intervention in a large cohort of adults with diabetes receiving care in U.S. integrated health care delivery systems: 2005–2011. Diabetes Care. 2016;39:363–70.

Yun JS, Ko SH, Ko SH, et al. Cardiovascular disease predicts severe hypoglycemia in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab J. 2015;39:498–506.

Sinclair AJ, Bellary S. Preventing hypoglycaemia: an elusive quest. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016;4:635–6.

Bonds DE, Miller ME, Bergenstal RM, et al. The association between symptomatic, severe hypoglycaemia and mortality in type 2 diabetes: retrospective epidemiological analysis of the ACCORD study. BMJ. 2010;340:b4909.

Gerstein HC, Miller ME, Byington RP, et al. Effects of intensive glucose lowering in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2545–59.

Aurobindo Pharma-Milpharm Ltd. Metformin 500 mg (PL 16363/0111) tablets SmPC. 2020. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/medicine/23244#gref. Accessed 09 Dec 2020.

Maruthur NM, Tseng E, Hutfless S, et al. Diabetes medications as monotherapy or metformin-based combination therapy for type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:740–51.

Sola D, Rossi L, Schianca GP, et al. Sulfonylureas and their use in clinical practice. Arch Med Sci. 2015;11:840–8.

Rosenstock J, Kahn SE, Johansen OE, et al. Effect of linagliptin vs glimepiride on major adverse cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes: the CAROLINA randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;322:1155–66.

de Jong M, van der Worp HB, van der Graaf Y, Visseren FLJ, Westerink J. Pioglitazone and the secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. A meta-analysis of randomized-controlled trials. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2017;16:134.

Lewis JD, Habel LA, Quesenberry CP, et al. Pioglitazone use and risk of bladder cancer and other common cancers in persons with diabetes. JAMA. 2015;314:265–77.

Zhu ZN, Jiang YF, Ding T. Risk of fracture with thiazolidinediones: an updated meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Bone. 2014;68:115–23.

Billington EO, Grey A, Bolland MJ. The effect of thiazolidinediones on bone mineral density and bone turnover: systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetologia. 2015;58:2238–46.

Schwartz AV, Chen H, Ambrosius WT, et al. Effects of TZD use and discontinuation on fracture rates in ACCORD bone study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100:4059–66.

Buse JB, Wexler DJ, Tsapas A, et al. 2019 Update to: management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes, 2018. A consensus report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care. 2018;2020(43):487–93.

Strain WD, Lukashevich V, Kothny W, Hoellinger MJ, Paldánius PM. Individualised treatment targets for elderly patients with type 2 diabetes using vildagliptin add-on or lone therapy (INTERVAL): a 24 week, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Lancet. 2013;382:409–16.

Sinha B, Ghosal S. Meta-analyses of the effects of DPP-4 inhibitors, SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP1 receptor analogues on cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, stroke and hospitalization for heart failure. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2019;150:8–16.

Milne N. How to use GLP-1 receptor agonist therapy safely and effectively. Diabetes Prim Care. 2020;22:135–6.

Novo Nordisk Limited. Rybelsus SmPC. 2020. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/11507/smpc#gref. Accessed 14 Oct 2020.

Strain WD, Griffiths J. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of GLP-1 receptor agonists and SGLT-2 inhibitors on cardiovascular outcomes in biologically healthy older adults. Br J Diabetes. 2021. https://doi.org/10.15277/bjd.2021.292.

Strain WD, Holst AG, Rasmussen S, Saevereid HA, James MA. Effects of liraglutide and semaglutide on stroke subtypes in patients with type 2 diabetes: a post hoc analysis of the LEADER, SUSTAIN 6 and PIONEER 6 trials (ePoster 398). European Society of Cardiology Congress (ESC 365), 29 Aug to 2 Sept 2020, Amsterdam.

Scheen AJ. Effects of glucose-lowering agents on surrogate endpoints and hard clinical renal outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab. 2019;45:110–21.

Brown P. How to use SGLT2 inhibitors safely and effectively. Diabetes Prim Care. 2021;23(1):5–7.

Davidson JA. SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with type 2 diabetes and renal disease: overview of current evidence. Postgrad Med. 2019;131:251–60.

Hsia DS, Grove O, Cefalu WT. An update on sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors for the treatment of diabetes mellitus. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2017;24:73–9.

Pettus J, Santos Cavaiola T, Tamborlane WV, Edelman S. The past, present, and future of basal insulins. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2016;32:478–96.

Novo Nordisk A/S. Tresiba (insulin degludec) summary of product characteristics. 2020. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/tresiba#product-information-section. Accessed 17 Dec 2020.

Sanofi-Aventis Deutschland GmBH. Toujeo summary of product characteristics. 2020. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/toujeo-previously-optisulin#product-information-section. Accessed 17 Dec 2020.

American Diabetes Association. 9. Pharmacologic approaches to glycemic treatment: standards of medical care in diabetes—2019. Diabetes Care. 2019;42:S90–S102.

McCoy RG, Lipska KJ, Van Houten HK, Shah ND. Paradox of glycemic management: multimorbidity, glycemic control, and high-risk medication use among adults with diabetes. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2020;8(1):e001007.

Weiner JZ, Gopalan A, Mishra P, et al. Use and discontinuation of insulin treatment among adults aged 75 to 79 years with type 2 diabetes. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:1633–41.

Abdelhafiz AH, Sinclair AJ. Deintensification of hypoglycaemic medications-use of a systematic review approach to highlight safety concerns in older people with type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Complicat. 2018;32:444–50.

Tan LF, Ho Wen Teng V, Seetharaman SK, Yip AW. Facilitating telehealth for older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond: strategies from a Singapore geriatric center. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2020;20:993–5.

Abrashkin KA, Poku A, Ball T, Brown ZJ, Rhodes KV. Ready or not: pivoting to video visits with homebound older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68:2469–71.

Isakovic M, Sedlar U, Volk M, Bester J. Usability pitfalls of diabetes mHealth apps for the elderly. J Diabetes Res. 2016;2016:1604609.

Mappangara I, Qanitha A, Uiterwaal C, Henriques JPS, de Mol B. Tele-ECG consulting and outcomes on primary care patients in a low-to-middle income population: the first experience from Makassar telemedicine program. Indones BMC Fam Pract. 2020;21:247.

Bergenstal RM, Layne JE, Zisser H, et al. Remote application and use of real-time continuous glucose monitoring by adults with type 2 diabetes in a virtual diabetes clinic. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2021;23(2):128–32.

Sy SL, Munshi MN. Caring for older adults with diabetes during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180:1147–8.

Valentine V, Goldman J, Shubrook JH. Rationale for, initiation and titration of the basal insulin/GLP-1RA fixed-ratio combination products, IDegLira and IGlarLixi, for the management of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Ther. 2017;8:739–52.

Min SH, Yoon JH, Hahn S, Cho YM. Comparison between SGLT2 inhibitors and DPP4 inhibitors added to insulin therapy in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review with indirect comparison meta-analysis. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2017;33(1):e2818.

Hope SV, Jones AG, Goodchild E, et al. Urinary C-peptide creatinine ratio detects absolute insulin deficiency in type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2013;30:1342–8.

Pernicova I, Korbonits M. Metformin—mode of action and clinical implications for diabetes and cancer. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2014;10:143–56.

[No authors listed]. Effect of intensive blood-glucose control with metformin on complications in overweight patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 34). UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Lancet. 1998;352:854–65.

Aroda VR, Edelstein SL, Goldberg RB, et al. Long-term metformin use and vitamin B12 deficiency in the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101:1754–61.

Seino S, Sugawara K, Yokoi N, Takahashi H. β-Cell signalling and insulin secretagogues: a path for improved diabetes therapy. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2017;19(Suppl 1):22–9.

Toh S, Hampp C, Reichman ME, et al. Risk for hospitalized heart failure among new users of saxagliptin, sitagliptin, and other antihyperglycemic drugs: a retrospective cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:705–14.

Simes BC, MacGregor GG. Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors: a clinician’s guide. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2019;12:2125–36.

Davidson MA, Mattison DR, Azoulay L, Krewski D. Thiazolidinedione drugs in the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus: past, present and future. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2018;48:52–108.

Acknowledgements

Funding

The journal’s Rapid Service Fee was funded by Novo Nordisk. The authors are also grateful to Dr Claire Ives of Novo Nordisk for providing a Medical Accuracy Review of the outline and final draft.

Medical Writing, Editorial, and Other Assistance

Medical writing support was provided by Jane Blackburn and editorial assistance provided by Helen Marshall, of Watermeadow Medical, an Ashfield company, part of UDG Healthcare plc, funded by Novo Nordisk.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Disclosures

W. David Strain has been awarded research grants from Takeda, Novo Nordisk and Novartis, and has received support from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Exeter Clinical Research Facility and the NIHR Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRC) for the South West Peninsula. He has also participated in speaker bureaus sponsored by AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, MSD, Napp, Novartis, Novo Nordisk and Takeda. Su Down has received funding from the following companies for providing educational sessions and documents, and for attending advisory boards: Abbott, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, MSD, Mylan, Napp, Novo Nordisk, Roche, Sanofi and Viatris. Pam Brown has received funding from Abbott, Boehringer Ingelheim, AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Janssen, MSD, Napp and Novo Nordisk for providing educational sessions and documents, and for attending advisory boards and conferences. Amar Puttanna has received honoraria, travel expenses or conference registration fees from MSD, Napp, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi, Takeda, Eli Lilly and AstraZeneca, and has also participated in advisory boards for AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Menarini, Janssen and Novo Nordisk. Alan Sinclair has received advisory fees and speaker fees from MSD, Takeda, Novo Nordisk, Bayer, Eli Lilly and Boehringer Ingelheim.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previous studies reported in the literature and on expert opinion. As such, it does not report results from studies performed by the authors with human participants or animals.

Data Availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article, as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Strain, W.D., Down, S., Brown, P. et al. Diabetes and Frailty: An Expert Consensus Statement on the Management of Older Adults with Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Ther 12, 1227–1247 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13300-021-01035-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13300-021-01035-9