Abstract

Background

Health behavior change can improve physical and psychosocial outcomes in internal medicine patients.

Purpose

This study aims to identify predictors for health behavior change after an integrative medicine inpatient program.

Method

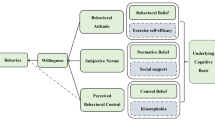

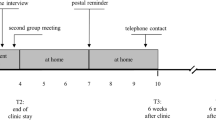

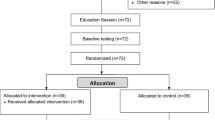

German internal medicine patients' (N = 2,486; 80 % female; 53.9 ± 14.3 years) practice frequency for aerobic exercise (e.g., walking, running, cycling, swimming), meditative movement therapies (e.g., yoga, tai ji, qigong), and relaxation techniques (e.g., progressive relaxation, mindfulness meditation, breathing exercises, guided imagery) was assessed at admission to a 14-day integrative medicine inpatient program, and 3, 6, and 12 months after discharge. Health behavior change was regressed to exercise self-efficacy, stage of change, and health locus of control (internal, external-social, external-fatalistic).

Results

Short-term increases in practice frequency were found for aerobic exercise: short- and long-term increases for meditative movement therapies and relaxation techniques (all p < 0.01). After controlling for sociodemographic characteristics, clinical characteristics, and health status, exercise self-efficacy or interactions of exercise self-efficacy with stage of change predicted increased practice frequency of aerobic exercise at 6 months; of meditative movement therapies at 3 and 6 months; and of relaxation techniques at 3, 6, and 12 months (all p < 0.05). Health locus of control predicted increased practice frequency of aerobic exercise at 3 months and of relaxation techniques at 3, 6, and 12 months (all p < 0.05).

Conclusion

Health behavior change after an integrative medicine inpatient program was predicted by self-efficacy, stage of change, and health locus of control. Considering these aspects might improve adherence to health-promoting behavior after lifestyle modification programs.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Roberts CK, Barnard RJ. Effects of exercise and diet on chronic disease. J Appl Physiol. 2005;98:3–30.

Campbell TC, Parpia B, Chen J. Diet, lifestyle, and the etiology of coronary artery disease: the Cornell China study. Am J Cardiol. 1998;82:18T–21T.

Expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults. Executive summary of the third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) expert panel on detection evaluation and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (adult treatment panel III). JAMA 2001;285:2486–97.

Lakka TA, Laaksonen DE, Lakka HM, et al. Sedentary lifestyle, poor cardiorespiratory fitness, and the metabolic syndrome. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35:1279–86.

van den Heuvel SG, Heinrich J, Jans MP, van der Beek AJ, Bongers PM. The effect of physical activity in leisure time on neck and upper limb symptoms. Prev Med. 2005;41:260–70.

Newsom JT, Huguet N, McCarthy MJ, et al. Health behavior change following chronic illness in middle and later life. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2012;67:279–88.

Ornish D, Scherwitz LW, Doody RS, et al. Effects of stress management training and dietary changes in treating ischemic heart disease. JAMA. 1983;249:54–9.

Nakao M, Myers P, Fricchione G, Zuttermeister PC, Barsky AJ, Benson H. Somatization and symptom reduction through a behavioral medicine intervention in a mind/body medicine clinic. Behav Med. 2001;26:169–76.

Paul A, Lauche R, Cramer H, Altner N, Dobos G. An Integrative Day-Care Clinic (IDCC) for chronically ill patients: concept and case presentation. Eur J Integr Med. 2012;4:e455–9.

Michalsen A, Grossman P, Lehmann N, et al. Psychological and quality-of-life outcomes from a comprehensive stress reduction and lifestyle program in patients with coronary artery disease: results of a randomized trial. Psychother Psychosom. 2005;74:344–52.

Lehmann N, Paul A, Moebus S, Budde T, Dobos GJ, Michalsen A. Effects of lifestyle modification on coronary artery calcium progression and prognostic factors in coronary patients—3-year results of the randomized SAFE-LIFE trial. Atherosclerosis. 2011;219:630–6.

Langhorst J, Mueller T, Luedtke R, et al. Effects of a comprehensive lifestyle modification program on quality-of-life in patients with ulcerative colitis: a twelve-month follow-up. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:734–45.

Elsenbruch S, Langhorst J, Popkirowa K, et al. Effects of mind-body therapy on quality of life and neuroendocrine and cellular immune functions in patients with ulcerative colitis. Psychother Psychosom. 2005;74:277–87.

Ornish D, Magbanua MJ, Weidner G. Changes in prostate gene expression in men undergoing an intensive nutrition and lifestyle intervention. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:8369–74.

Daubenmier JJ, Weidner G, Sumner MD, et al. The contribution of changes in diet, exercise, and stress management to changes in coronary risk in women and men in the multisite cardiac lifestyle intervention program. Ann Behav Med. 2007;33:57–68.

Dobos G, Altner N, Lange S, et al. Mind–body medicine as a part of German integrative medicine. Bundesgesundheitsbl Gesundheitsforsch Gesundheitsschutz. 2006;49:723–8.

Lauche R, Cramer H, Paul A, Dobos GJ, Rampp T. Introducing integrative integrated migraine care (IIMC): a model and case presentation. Eur J Integr Med. 2012;4:e37–40.

Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977;84:191–215.

Ewart CK, Taylor CB, Reese LB, DeBusk RF. Effects of early postmyocardial infarction exercise testing on self-perception and subsequent physical activity. Am J Cardiol. 1983;51:1076–80.

Rogers LQ, Matevey C, Hopkins-Price P, Shah P, Dunnington G, Courneya KS. Exploring social cognitive theory constructs for promoting exercise among breast cancer patients. Cancer Nurs. 2004;27:462–73.

Karvinen KH, Courneya KS, Campbell KL, et al. Correlates of exercise motivation and behavior in a population-based sample of endometrial cancer survivors: an application of the Theory of Planned Behavior. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2007;4:21.

Medina-Mirapeix F, Escolar-Reina P, Gascón-Cánovas JJ, Montilla-Herrador J, Jimeno-Serrano FJ, Collins SM. Predictive factors of adherence to frequency and duration components in home exercise programs for neck and low back pain: an observational study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2009;10:155.

Wallston KA. Hocus-pocus, the focus isn't strictly on locus: Rotter's social learning theory modified for health. Cogn Ther Res. 1992;16:183–99.

Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: toward an integrative model of change. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1983;51:390–5.

Wallston KA. Control and health. In: Anderson N, editor. Encyclopedia of health & behavior. Volume one. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2004. p. 217–20.

Prochaska JO, Velicer WF. The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. Am J Health Promot. 1997;12:11–2.

Marcus BH, Simkin LR. The transtheoretical model: applications to exercise behaviour. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1994;26:1400–4.

Plotnikoff RC, Hotz SB, Birkett NJ, Courneya KS. Exercise and the transtheoretical model: a longitudinal test of a population sample. Prev Med. 2001;33:441–52.

Evers KE, Prochaska JO, Johnson JL, Mauriello LM, Padula JA, Prochaska JM. A randomized clinical trial of a population- and transtheoretical model-based stress-management intervention. Health Psychol. 2006;25:521–9.

Rotter JB. Generalized expectancies for internal vs. external control of reinforcement. Psychol Monogr. 1966;80:1–28.

Wallston KA. Multidimensional health locus of control scale. In: Christensen AJ, Martin R, Smyth J, editors. Encyclopedia of health psychology. New York: Kluwer/Plenum; 2004. p. 171–2.

Slenker SE, Price JH, O'Connell JK. Health locus of control of joggers and nonexercisers. Percept Mot Skills. 1985;61:323–8.

Norman P, Bennett P, Smith C, Murphy S. Health locus of control and leisure-time exercise. Personal Individ Differ. 1997;23:769–74.

Dobos GJ, Deuse U, Michalsen A, editors. Chronische Erkrankungen integrativ: Konventionelle und komplementäre Therapie. München: Urban & Fischer; 2006.

Hoffmann B, Moebus S, Michalsen A, et al. Health-related control belief and quality of life in chronically ill patients after a behavioral intervention in an integrative medicine clinic—an observational study. Forsch Komp Klas Nat. 2004;11:159–70.

Lauche R, Cramer H, Moebus S, Paul A, Michalsen A, Langhorst J, et al. Effects of a 14-day inpatient stay at a clinic for internal and integrative medicine—an observational study. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012:875874.

Michalsen A, Hoffmann B, Moebus S, Bäcker M, Langhorst J, Dobos GJ. Incorporating of fasting therapy in an integrative medicine ward: evaluation of outcome, safety, and effects of lifestyle adherence in a large prospective cohort study. J Altern Complement Med. 2005;11:601–7.

Benson H, Stuart M. The wellness book. Mind–body medicine. New York: Fireside; 1999.

Kabat-Zinn J. An outpatient program in behavioral medicine for chronic pain patients based on the practice of mindfulness meditation: theoretical considerations and preliminary results. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1982;4:33–47.

Kabat-Zinn J. Full catastrophe living: using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness. New York: Delacorte; 1990.

Fuchs R, Schwarzer R. Selbstwirksamkeit zur sportlichen Aktivität: reliabilität und Validität eines neuen Meßinstruments. Z Differ Diagn Psychol. 1994;15:141–54.

Hasenbring M. Laienhafte Ursachenvorstellungen und Erwartungen zur Beeinflussbarkeit einer Krebserkrankung - erste Ergebnisse einer Studie an Krebspatiente. In: Bischoff C, Zenz H, editors. Patientenkonzepte von Körper und Krankheit. Bern: Hans Huber; 1989. p. 25–38.

World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision. http://apps.who.int/classifications/icd10/browse/2010/en. Accessed 06 Aug 2012.

Bullinger M, Kirchberger I. SF-36 Fragebogen zum Gesundheitszustand. Göttingen: Hogrefe; 1998.

Herrmann C, Buss U, Snaith RP. Hospital anxiety and depression scale—Deutsche version (HADS-D). Manual. Bern: Hans Huber; 1995.

Larkey L, Jahnke R, Etnier J, Gonzalez J. Meditative movement as a category of exercise: implications for research. J Phys Act Health. 2009;6:230–8.

Mazzeschi C, Pazzagli C, Buratta L, Reboldi GP, Battistini D, Piana N, et al. Mutual interactions between depression/quality of life and adherence to a multidisciplinary lifestyle intervention in obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:E2261–5.

Wallston KA. Control beliefs. In: Smelser NJ, Baltes PB, editors. International encyclopedia of the social and behavioral sciences. Oxford: Elsevier Science; 2001. p. 2724–6.

Luszczynska A, Schwarzer R. Multidimensional health locus of control: comments on the construct and its measurement. J Health Psychol. 2005;10:633–42.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all physicians, nurses, staff members, and patients for their help in data collection. This study was part of a quality assurance program and supported by a research grant from the Karl and Veronica Carstens Foundation, Essen, Germany.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cramer, H., Lauche, R., Moebus, S. et al. Predictors of Health Behavior Change After an Integrative Medicine Inpatient Program. Int.J. Behav. Med. 21, 775–783 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-013-9354-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-013-9354-6