Abstract

Background

Cognitive models explaining medically unexplained complaints propose that activating illness-related memory causes increased complaints such as pain. However, our previous studies showed conflicting support for this theory.

Purpose

Illness-related memory is more likely to influence reporting of complaints when its activation is enmeshed with that of self-related memory. We, therefore, investigated whether inducing this association would cause a stronger decrease in pain tolerance. In addition, we examined whether SFA acted as a moderator of this effect.

Methods

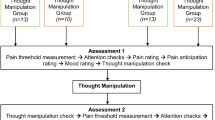

We used subliminal evaluative conditioning (SEC) to induce an association between activated self-related and illness-related memory. Seventy-six participants were randomly assigned to four combinations of two priming factors: (1) the self-referent word “I” versus the nonself-referent “X” to manipulate activated self-related memory and (2) health complaint (HC) words versus neutral words to manipulate activated illness-related memory. Pain tolerance was assessed using a cold pressor task (CPT).

Results

Participants primed with the self-referent “I” and HC words did not demonstrate the expected lower pain tolerance. However, SFA acted as a moderator of the main effect of the self-prime: priming with “I” resulted in increased pain tolerance in participants with low SFA.

Conclusions

The current study did not support the hypothesis that associations between activated self-related memory and illness-related memory cause increased reporting of complaints. Instead, activating self-related memory increased pain tolerance in participants with low SFA. This seems to indicate that the self-prime might cause an increase in SFA and suggests possible new ways to promote adaptive coping with pain.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Eriksen HR, Ursin H. Subjective health complaints, sensitization, and sustained cognitive activation (stress). J Psychosom Res. 2004;56(4):445–8.

Peveler R, Kilkenny L, Kinmonth AL. Medically unexplained physical symptoms in primary care: a comparison of self-report screening questionnaires and clinical opinion. J Psychosom Res. 1997;42(3):245–52.

Page LA, Wessely S. Medically unexplained symptoms: exacerbating factors in the doctor–patient encounter. J R Soc Med. 2003;96(5):223–7.

Henningsen P, Zipfel S, Herzog W. Management of functional somatic syndromes. Lancet. 2007;369(9565):946–55.

Henningsen P, Zimmermann T, Sattel H. Medically unexplained physical symptoms, anxiety, and depression: a meta-analytic review. Psychosom Med. 2003;65(4):528–33.

Brosschot JF. Cognitive–emotional sensitization and somatic health complaints. Scand J Psychol. 2002;43(2):113–21.

Brown RJ. Psychological mechanisms of medically unexplained symptoms: an integrative conceptual model. Psychol Bull. 2004;130(5):793–812.

Pennebaker JW. Selective monitoring of illness symptoms. The psychology of physical symptoms. New York: Springer; 1982. p. 48.

Watson D, Pennebaker JW. Health complaints, stress, and distress: exploring the central role of negative affectivity. Psychol Rev. 1989;96(2):234–54.

Fenigstein A, Scheier MF, Buss AH. Public and private self-consciousness: assessment and theory. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1975;43(4):522.

Cioffi D. Beyond attentional strategies: cognitive–perceptual model of somatic interpretation. Psychol Bull. 1991;109(1):25–41.

Williams PG, Wasserman MS, Lotto AJ. Individual differences in self-assessed health: an information-processing investigation of health and illness cognition. Heal Psychol. 2003;22:3–11.

Suls J, Fletcher B. Self-attention, life stress, and illness: a prospective study. Psychosom Med. 1985;47(5):469–81.

Skelton JA, Strohmetz DB. Priming symptom reports with health-related cognitive activity. Personal Soc Psychol Bull. 1990;16(3):449–64.

Rief W, Broadbent E. Explaining medically unexplained symptoms—models and mechanisms. Clin Psychol Rev. 2007;27(7):821–41. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2007.07.005.

de Wied M, Verbaten MN. Affective pictures processing, attention, and pain tolerance. Pain. 2001;90(1–2):163–72.

Godinho F, Magnin M, Frot M, Perchet C, Garcia-Larrea L. Emotional modulation of pain: is it the sensation or what we recall? J Neurosci. 2006;26(44):11454–61.

Meerman EE, Verkuil B, Brosschot JF. Decreasing pain tolerance outside of awareness. J Psychosom Res. 2011;70(3):250–7.

Meerman EE, Brosschot JF, Verkuil B. The effect of priming illness memory on pain tolerance: a failed replication. J Psychosom Res. 72:408-9.

Pincus T, Morley S. Cognitive-processing bias in chronic pain: a review and integration. Psychol Bull. 2001;127(5):599–617.

Riketta M, Dauenheimer D. Manipulating self-esteem with subliminally presented words. Eur J Soc Psychol. 2003;33(5):679–99.

Dijksterhuis A. I like myself but I don't know why: enhancing implicit self-esteem by subliminal evaluative conditioning. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2004;86(2):345–55.

Hull JG, Slone LB, Meteyer KB, Matthews AR. The nonconsciousness of self-consciousness. J Personal Soc Psychol. 2002;83(2):406–24.

Verkuil B, Brosschot JF, Thayer JF. A sensitive body or a sensitive mind? Associations among somatic sensitization, cognitive sensitization, health worry, and subjective health complaints. J Psychosom Res. 2007;63(6):673–81.

Vleeming RG, Engelse JA. Assessment of private and public self-consciousness: a Dutch replication. J Personal Assess. 1981;45(4):385–9.

Kiefer M. The N400 is modulated by unconsciously perceived masked words: further evidence for an automatic spreading activation account of N400 priming effects. Cogn Brain Res. 2002;13(1):27–39.

Levy B. Improving memory in old age through implicit self-stereotyping. J Personal Soc Psychol. 1996;71(6):1092–107.

Pierce T, Lydon J. Priming relational schemas: effects of contextually activated and chronically accessible interpersonal expectations on responses to a stressful event. J Personal Soc Psychol. 1998;75(6):1441–8.

Spalding LR, Hardin CD. Unconscious unease and self-handicapping: behavioral consequences of individual differences in implicit and explicit self-esteem. Psychol Sci. 1999;10(6):535.

Kawakami K, Dovidio JF, Dijksterhuis A. Effect of social category priming on personal attitudes. Psychol Sci. 2003;14(4):315.

Macmillan NA, Creelman CD. Detection theory: a user's guide. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2005.

Price DD, McGrath PA, Rafii A, Buckingham B. The validation of visual analogue scales as ratio scale measures for chronic and experimental pain. Pain. 1983;17(1):45–56.

Bargh JA, Chartrand TL. The mind in the middle: a practical guide to priming and automaticity research. In: Reis HT, Judd CM, editors. Handbook of research methods in social and personality psychology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2000. p. 253–85.

Levy BR, Hausdorff JM, Hencke R, Wei JY. Reducing cardiovascular stress with positive self-stereotypes of aging. J Gerontol Ser B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2000;55(4):205–13.

Lowery BS, Eisenberger NI, Hardin CD, Sinclair S. Long-term effects of subliminal priming on academic performance. Basic Appl Soc Psychol. 2007;29(2):151.

Steyerberg WE, Harrell Jr FE. Statistical models for prognostication. In: D MM, Lynn J, editors. Interactive textbook of symptom research: methods and opportunities. 2003.

Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics. Boston: Allyn and Bacon; 2001.

Simmons JP, Nelson LD, Simonsohn U. False-positive psychology: undisclosed flexibility in data collection and analysis allows presenting anything as significant. Psychol Sci In Press.

Miller GA, Chapman JP. Misunderstanding analysis of covariance. J Abnorm Psychol. 2001;110(1):40–8.

Quirin M, Bode RC, Kuhl J. Recovering from negative events by boosting implicit positive affect. Cogn Emot. 2011;25(3):559–70.

Hofmann W, De Houwer J, Perugini M, Baeyens F, Crombez G. Evaluative conditioning in humans: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 2010;136:390–421.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO) to J.F.B. The funders did not have any role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Meerman, E.E., Brosschot, J.F., van der Togt, S.A.M. et al. The Effect of Subliminal Evaluative Conditioning of Cognitive Self-schema and Illness Schema on Pain Tolerance. Int.J. Behav. Med. 20, 627–635 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-012-9270-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-012-9270-1