Abstract

Introduction

The Satisfaction with Iron Chelation Therapy (SICT) instrument was developed based on a literature review, in-depth patient and clinician interviews, and cognitive debriefing interviews. An, open-label, single arm, multicenter trial evaluating the efficacy and safety of deferasirox in patients diagnosed with transfusion-dependent iron overload, provided an opportunity to assess the psychometric measurement properties of the instrument.

Methods

Psychometric analyses were performed using data at baseline from 273 patients with a range of transfusion-dependent iron overload conditions who were participating in a multinational study. Responsiveness was further evaluated for all patients who also had subsequent satisfaction domain scores collected at week 4.

Results

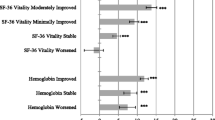

Baseline SICT domain scores had acceptable floor and ceiling effects and internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s alpha: 0.75–0.85). Item discriminant and item convergent validity were both excellent although one item in each analysis did not meet the specified criterion. Small to moderate correlations were observed between SICT and Short Form 36 Health Survey (SF-36) domain scores. Patients with the highest levels of serum ferritin at baseline (>3100 ng/mL) were the least satisfied about the Perceived Effectiveness of ICT and vice versa. Satisfaction improved in all patients, although there were no clear differences observed between groups of patients defined according to changes in serum ferritin levels from baseline to week 4 (stable, improved, or worsened).

Conclusions

The SICT domains are reliable and valid. Further testing using a more specific criterion (such as assessing patient global ratings of change in satisfaction domains that correspond to the SICT domains) could help to establish with greater confidence the responsiveness of the instrument.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Olivieri NF, Brittenham GM. Iron-chelating therapy and the treatment of thalassemia. Blood. 1997;89:739–761.

Information Center for Sickle Cell and Thalassemic Disorders. Effects of iron overload: hemochromatosis, tranfusional iron overload. 1999. Available at: http://sickle.bwh.harvard.edu/hemochromatosis.html. Accessed June 26, 2010.

Inati A. Recent advances in improving the management of sickle cell disease. Blood Rev. 2009;23(Suppl 1):S9–13.

Ismail A, Campbell M, Ibrahim H, Jones G. Health related quality of life in Malaysian children with thalassaemia. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4:39.

Vidler V. Compliance with iron chelation therapy in beta thalassaemia. Paediatr Nurs. 1998;10:17–18.

Payne KA, Desrosiers MP, Caro JJ, et al. Clinical and economic burden of infused iron chelation therapy (ICT) in the United States. Transfusion. 2007;47:1820–1829.

Payne KA, Rofail D, Baladi JF, et al. Iron chelation therapy: clinical effectiveness, economic burden and quality of life in patients with iron overload. Adv Ther. 2008;25:725–742.

Scalone L, Mantovani LG, Krol M, et al. Costs, quality of life, treatment satisfaction and compliance in patients with beta-thalassemia major undergoing iron chelation therapy: the ITHACA study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24:1905–1917.

Shumaker SA, Berzon RA. The international assessment of HRQL. Theory, translations, measurement and analysis. Oxford, UK: Rapid Communications; 1995.

Rebulla P. Transfusion reac tions in thalassemia. A survey from the Cooleycare programme. The Cooleycare Cooperative Group. Haematologica. 1990;75(Suppl 5):122–127.

Giardina PJ, Grady RW. Chelation therapy in betathalassemia: an optimistic update. Semin Hematol. 2001;38:360–366.

Alymara V, Bourantas D, Chaidos A, et al. Effectiveness and safety of combined iron-chelation therapy with deferoxamine and deferiprone. Hematol J. 2004;5:475–479.

Cappellini MD. Removing the burden - iron overload and deferasirox (ICL670). US Oncological Disease 2006;67-68. Available at: www.touchcardiology.com/files/article_pdfs/onco_6726. Accessed June 16, 2010.

Vichinsky E, Pakbaz Z, Onyekwere O, et al. Patient-reported outcomes of deferasirox (Exjade, ICL670) versus deferoxamine in sickle cell disease patients with transfusional hemosiderosis. Substudy of a randomized open-label phase II trial. Acta Haematol. 2008;119:133–141.

Abetz L, Baladi JF, Jones P, Rofail D. The impact of iron overload and its treatment on quality of life: results from a literature review. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4:73.

Rofail D, Abetz L, Viala M, Gait C, Baladi JF, Payne K. Satisfaction and adherence in patients with iron overload receiving iron chelation therapy as assessed by a newly developed questionnaire. Value Health. 2009;12:109–117.

Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Medical Care. 1992;30:473–483.

Guy RG, Norvell M. The neutral point on a Likert Scale. J Psychol. 1977;95:199–204.

Ray JJ. Acquiescence and problems with forced-choice scales. J Social Psychol. 1990;130:397–399.

Ware JE, Kosinski M, Dewey JE. How to score version two of the SF-36 health survey. Lincoln, RI: QualityMetric Inc.; 2000.

Cronbach LJ. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika. 1951;16:297–334.

Nunnally JC. Psychometric Theory. 2nd edition. New York, USA: McGraw Hill; 1978.

Campbell DT, Fiske DW. Convergent and discriminant validation by the multitrait-multimethod matrix. Psychol Bull. 1959;56:81–105.

Rock DL, Fordyce WE. Item convergent validity: a new method of analysis for frequency of continuously scaled data. J Exp Educ. 1982;51:38–41.

Kline P. Handbook of psychological testing. 2nd edition. London, UK: Routledge; 1999.

Juniper EF, Guyatt GH, Willan A, Griffith LE. Determining the minimal important change in a disease-specific quality of life questionnaire. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47:81–87.

Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd edition. New York, USA: Erlbaum; 1988.

Addison GM, Beamish MR, Hales CN, Hodgkins M, Jacobs A, Llewellin P. An immunoradiometric assay for ferritin in the serum of normal subjects and patients with iron deficiency and iron overload. J Clin Pathol. 1972;25:326–329.

Jacobs A, Miller F, Worwood M, Beamish MR, Wardrop CA. Ferritin in the serum of normal subjects and patients with iron deficiency and iron overload. Br Med J. 1972;4:206–208.

Guyatt GH, Osoba D, Wu AW, Wyrwich KW, Norman GR. Methods to explain the clinical significance of health status measures. Mayo Clin Proc. 2002;77:371–383.

Hays RD, Woolley JM. The concept of clinically meaningful difference in health-related quality-of-life research. How meaningful is it? Pharmacoeconomics. 2000;18:419–423.

Hall JA, Dornan MC. Patient sociodemographic characteristics as predictors of satisfaction with medical care: a meta-analysis. Soc Sci Med. 1990;30:811–818.

Lee Y, Kasper JD. Age differences in ratings of medical care among older adults living in the community. Aging. 1999;11:132–135.

Byles JE, Hanrahan PF, Schofield MJ. “It would be good to know you’re not alone”: the health care needs of women with menstrual symptoms. Fam Prac. 1997;14:249–254.

Hays R, Hayashi T. Beyond internal consistency reliability: rationale and user’s guide for Multi-trait Analysis Program on the microcomputer. Behav Res Meth Instrum Comput. 1990;22:167–175.

Cattell RB. Personality and Mood by Questionnaire. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1973.

Sitzia J, Wood N. Patient satisfaction: a review of issues and concepts. Soc Sci Med. 1997;45:1829–1843.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rofail, D., Viala, M., Gater, A. et al. An instrument assessing satisfaction with iron chelation therapy: Psychometric testing from an open-label clinical trial. Adv Therapy 27, 533–546 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-010-0049-y

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-010-0049-y