Abstract

Limited empirical evidence is available regarding the uptake and effectiveness of school-based mental health and wellbeing programs implemented in Australian schools. This study aimed to characterise the delivery of programs in primary (elementary) schools across New South Wales, Australia, and to assess this information against published ratings of program effectiveness. Delivery of programs in four health-promoting domains—creating a positive school community; teaching social and emotional skills; engaging the parent community; and supporting students experiencing mental health difficulties—were reported by 597 school principals/leaders via online survey. Although three quarters of principals reported implementing at least one program, many of these programs were supported by little or no evidence of effectiveness. There was also variability in the use of evidence-based programs across the four domains. Findings indicate a need to provide educators with improved support to identify, implement, and evaluate effective evidenced-based programs that promote student mental health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Schools in Australia and internationally are increasingly being tasked with an important role in fostering students’ mental health and wellbeing alongside their academic development. Evidence that social-emotional competency is supportive of students’ academic and behavioural development, in addition to their mental health and wellbeing (Grove & Laletas, 2020), is leading to the inclusion of social-emotional learning (SEL) as a key element in systemic reform initiatives based on the implementation of multi-tiered systems of support frameworks (Stoiber & Gettinger, 2016). Reform progress is most advanced in the United States (US), where the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL, 2013; Weissberg et al., 2015), was established in 1994 with the aim of generating high-quality evidence-based SEL programs for implementation in schools. These programs deliver formal teaching, modelling, and skills practice in five core social-emotional competencies: recognising and managing emotions and behaviours, setting and achieving positive goals, appreciating the perspectives of others, establishing and maintaining positive relationships, and making responsible decisions (Elliott et al., 2015).

Consistent with an Implementation Science approach to quality improvement in education (Fixsen et al., 2015; Meyers et al., 2019; Nilsen, 2015; Nordstrum et al., 2017), the online CASEL Guide (CASEL, 2013) adopts a systematic framework (with criteria and rationale) for evaluating the quality of universalFootnote 1 programs teaching these five competencies and provides best-practice guidelines to school leaders and to policy makers on how to select and implement SEL programs across preschool, elementary, middle, and high school grades. Meta-analytic evidence (Durlak et al., 2011) demonstrates that the enhanced social and emotional competencies resulting from these SEL programs (Hedge’s g effect size [ES] 0.57) may bring about reductions in conduct problems (ES 0.22) and emotional distress (ES 0.24), and improvements in social behaviour (ES 0.24) and academic learning outcomes (ES 0.27), which can remain over follow-up intervals of six months to 18 years (Taylor et al., 2017). However, as SEL is embedded in the cultural context in which it is taught (Collie et al., 2017), school leaders and policy makers outside the US require similar evidence hubs providing high-quality information on the effectiveness of programs, and effective supports for program implementation, in their local communities. To varying degrees, the CASEL model has been adapted in other jurisdictions [e.g., the United Kingdom (Early Intervention Foundation, 2014)] as the evidence-base from local evaluations of school-based mental health promotion programs becomes available. In Australia, however, few impact evaluations of such programs have been undertaken.

Little is known regarding the uptake of SEL and other mental health and wellbeing programs by Australian schools, and particularly, the extent to which schools implement programs with an existing evidence base. The Australian Commonwealth and State Education Ministers have recognised the importance of integrating the teaching of social and emotional competencies with academic learning (Education Council, 2019; MCEETYA, 2008). Accordingly, formal teaching and practice of four of the five CASEL competencies is operationalised in the Australian Curriculum through the Personal and Social Capability (ACARA, 2020) strand of the General Capabilities, which develops skills in self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, and social management (relationship skills). While the idea of general capabilities is widely supported by educators, who recognise their importance for students, the matrix design of the Australian Curriculum, together with the emphasis placed on subject curriculum, reduces the likelihood of teachers explicitly including the capabilities in their planning and teaching, especially those capabilities not perceived to directly support subject learning (Gilbert, 2019).

Further, while all Australian schools are required to deliver a mental health and wellbeing curriculum, the stratified provision of educational services in Australia (by States and Territories and government and non-government providers) has spawned a diversity of policies governing this practice. This has left schools to navigate a plethora of programs and service providers in planning and implementing their mental health programming, within a school accountability context that privileges narrow forms of academic achievement and which provides variable amounts of direction and support for evidence-based program identification and implementation (Bowles et al., 2017; Powell & Graham, 2017; Wyn, 2007). Recent reviews describing the cultural and contextual characteristics that have shaped SEL delivery in Australia have highlighted this flexibility in program selection relative to more directed approaches often adopted in other jurisdictions (Collie et al., 2017; Humphrey, 2013). While seeking to respect the professionalism and professional judgement of educators, such flexibility also creates additional burden for those educators who may not have the time or requisite research knowledge to decipher the most appropriate programs from the many that are marketed to them. The sheer number and diversity of programs in operation across Australian schools also presents challenges to deriving an evidence-base on the effectiveness of school-based mental health programs in diverse Australian contexts.

Recent Initiatives to Support School-Based Mental Health Provision in Australia

A series of national initiatives funded by the Australian Government has provided some support for local delivery of school-based mental health promotion, prevention, and early intervention (Collie et al., 2017; Humphrey, 2013). These comprised MindMatters for secondary (middle/high) school students (7th through 12th grades; ages ~ 12–18 years) commencing in 2000, KidsMatter Primary for primary (elementary) school students (foundation [kindergarten] through 6th grade; ages ~ 5–12 years) from 2006, and KidsMatter Early Childhood for preschool aged children from 2010 (Graetz et al., 2008; Littlefield et al., 2017). In November 2018, these were integrated, and replaced by Be You—a single national education-based initiative to support the mental health and wellbeing of children and young people from birth to school-leaving (Australian Government, 2021). These initiatives have provided flexible training, information, and resources to schools, including an online directory of mental health-related programs (including SEL) from which schools could select those best suited to their needs and context. However, unlike the CASEL and Early Intervention Foundation approaches, the mental health programs featured in these initiatives were not restricted to those supported by evidence of their effectiveness. To our knowledge, the extent to which school leaders in Australia prefer evidence-based programs over other available programs has not previously been investigated. This information is a critical first step to better understanding the navigational challenges educators experience and how program information provision might be improved.

Of particular relevance to the present study characterising the use of primary school-based mental health and wellbeing programs, the KidsMatter Primary (2006–2018) initiative (Graetz et al., 2008; Littlefield et al., 2017) provided a framework through which primary schools were supported to deliver a universal approach to improving all children’s mental health and wellbeing, supplemented with targeted early intervention strategies for students at risk or already experiencing mental health difficulties. It provided a conceptual framework (rationale) to support a whole-of-school approach and implementation process, comprising step-by-step guides to support implementation and maintenance, as well as staff training, and support personnel. An online Programs Guide, compiled in 2009 by the Australian Psychological Society, provided information on a suite of approximately 100 programs suitable for primary school-aged students. The programs were mapped to the four components of the KidsMatter framework identified as important for driving whole-school improvement (Slee et al., 2009):

Component 1: Creating a positive school community through programs building respectful relationships and a sense of belonging and inclusion;

Component 2: Providing social and emotional learning for students through formal teaching of social and emotional competences in the curriculum and relevant opportunities for the practice of these skills, according to the five CASEL competencies of self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, social management (relationship skills), and responsible-decision making;

Component 3: Working with parents and carers of children, including programs providing support and information about parenting, children’s development, and mental health;

Component 4: Supporting children at risk of or experiencing mental health difficulties, via school-based programs for children with emotional, social, and behavioural problems, and policies and practices to support improved educator capacity to recognise early problems and assist families in accessing relevant health and community service providers.

For each of the SEL programs featured in Component 2, the Program Guide provided additional information regarding that program’s area of focus (i.e., the CASEL competencies developed), the extent of available evidence supporting its effectiveness, and the degree of formal structure provided to the SEL sessions and opportunities for skills practice. Notable variation between programs featured in the Guide existed not only in the extent of available evidence supporting their effectiveness, but also in their coverage of the CASEL competencies and structured learning sessions. More recently, as part of a wider systematic review, more than 200 school-based mental health and wellbeing programs available in Australia were reviewed (Dix et al., 2020), with notable variability in the quality of evidence supporting program effectiveness. Less than one quarter (23%) of programs had any associated published studies or reports assessing their impact on behavioural outcomes, and only one Australian study was of sufficient quality to meet the criteria for inclusion in the broader systematic review.

The Present Study

Establishing the uptake of mental health promotion and early intervention programs by Australian schools, particularly the extent to which evidence-based programs are implemented, may help inform the development of more effective policy and resourcing to support school-based mental health promotion in Australia, and provide a baseline against which future improvements in practice can be evaluated. The present study thus sought to characterise the diversity of school-based mental health and wellbeing programs being delivered in the Australian state with the largest population of primary school students, New South Wales (NSW). The study aimed to identify the variety and extent of uptake of different programs delivered in both government and non-government schools across the state, the length of program delivery, the grade/stage levels targeted by the programs, and school leaders’ perceptions of their effectiveness. These program data, reported by primary school principals via online survey, were assessed according to the four components of school-based mental health promotion implemented within the KidsMatter framework, and in the context of the supporting evidence available for these programs, including the recent evidence ratings conducted by Dix et al. (2020).

Method

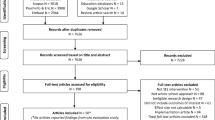

Recruitment

In November 2015, the school principals (or their delegate from the school leadership team) of 689 government and non-government (Catholic, Independent) schools in NSW with a 6th-grade enrolment were invited to participate in an online survey of school-based mental health promotion policies and practices. These were the principals of a subset (83%) of 829 schools who, as part of the NSW Child Development Study (Carr et al., 2016, Green et al., 2018), had administered an online, self-reported Middle Childhood Survey (MCS) of child mental health and wellbeing to 27,808 6th-grade students during 2015 (Laurens et al., 2017) and had indicated willingness to be contacted regarding a principal survey. According to data obtained from the Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority, these 689 schools constituted almost one third (29.1%) of the 2,371 schools in NSW with a 6th-grade enrolment during 2015.

Procedure

Participants received information about the study and a unique link to the online survey via email. Responses were monitored during a two-month administration period, with system-generated reminder emails issued to non-responders, followed by a telephone reminder.

Instrument

The online Survey of School Promotion of Emotional and Social Health (SSPESH) comprised two sections. The first section was a 14-item instrument that assessed the implementation of whole-school policies and practices in the four health-promoting components (creating a positive school community, teaching social and emotional skills, engaging the parent community, and supporting students experiencing mental health difficulties). The second section (detailed below) recorded the wellbeing programs and frameworks being implemented in a school. Data from the first section of the survey have been analysed in detail previously (Dix et al., 2019). The present study analyses data from the second section of the survey.

Principals could report the delivery of up to five (5) school-based mental health promotion programs by selecting from a menu of 96 programs featured in the KidsMatter Primary Programs Guide (Littlefield et al., 2017). Principals could also respond via free-text to provide detail on programs that were used in their school but which were not listed in the program menu. For each program reported, principals were asked to indicate:

-

I.

The calendar year in which delivery of the program in their school commenced—six response options, ranging from 2010 or earlier (scored 6) to 2015 (scored 1);

-

II.

The school grades targeted by the program – five response options: Early Stage 1 (Kindergarten); Stage 1 (Grades 1–2); Stage 2 (Grades 3–4); Stage 3 (Grades 5–6); or All or most stages; and

-

III.

The principal’s perception of the effectiveness of the program—four response options: Not at all (scored 0); Somewhat (1); Moderately (2); and Extremely (3).

Principals were also asked to report their school’s implementation of any whole-school mental health and wellbeing frameworks. Principals could indicate by check-box their school’s implementation of up to nine frameworks commonly adopted in Australian schools by 2015, including: KidsMatter Primary; KidsMatter Early Childhood; MindMatters (pre-2014) or MindMatters Redeveloped (from 2014); School Wide Positive Behaviour Support/Positive Behaviour for Learning; Health Promoting Schools; Cybersafety; Child Protection; and Dare to Lead, and/or nominate alternative frameworks by free-text. Although these frameworks vary in the extent to which they provide a conceptual framework (rationale) to support a whole-of-school prevention approach, a detailed implementation process, staff training, and support personnel, they nonetheless provide some indication of whether school principals access external resources to promote mental health and wellbeing in their school.

Analytical Approach

Programs Selected from the Programs Menu

The programs delivered were categorised according to each of the four health-promoting components (creating a positive school community, teaching social and emotional skills, engaging the parent community, and supporting students experiencing mental health difficulties), and their effectiveness in eliciting positive effects on behavioural outcomes was rated drawing on available evidence (Dix et al., 2020), rated at three levels: ‘low’—programs for which an underlying theoretical framework was identified but no published study of program effectiveness was available; ‘medium’—programs for which there was only indirect evidence available (i.e., empirical evidence of effectiveness from similar/related programs, but no research involving the specific program); and ‘high’—published studies or reports on the program’s impact on behavioural outcomes available, but without consideration of the methodological quality of those investigations.

For programs delivering formal teaching of SEL competencies (Component 2), we additionally drew on the information compiled by the Australian Psychological Society for the KidsMatter Primary Programs Guide, which remained publicly available online at the time of survey completion in 2015. This information provided ratings of: (i) the evidence of program effectiveness (i.e., availability of empirical studies demonstrating positive program impacts on behavioural measures); (ii) degree of structure to the lessons; and (iii) coverage of the five CASEL social and emotional competencies within each program. Each of these three ratings comprised four levels, as detailed in Table 1.

Analyses were conducted to determine whether any of four demographic features of a school were associated with the delivery of a program in each component. These school demographics included: (i) the Index of Community Socio-Educational Advantage 2014, which is derived for each school in Australia, based on information including parental education and occupation, the school’s geographical location, and the proportion of Indigenous students (ACARA, 2015); (ii) the location of the school (metropolitan, regional or remote); (iii) the total enrolment size; and (iv) the number of full-time equivalent teaching staff. Bivariate associations between each demographic variable and the delivery of a program in each component were examined using analysis of variance (for continuous variables) or chi-square (for categorical variables). To correct for the conduct of multiple comparisons (n = 16), a p value of < 0.003 was applied to determine statistical significance.

Other Programs Detailed via Free-Text Response

Any free-text response providing additional information relating to the 96 programs listed in the selection menu was incorporated into that analysis. Responses naming other programs were classified based on the available information, supplemented by further online research, according to whether the program derived from a provider external to the school or was developed “in-house”. Responses were also classified according to the skill targeted for development (e.g., resilience, peer relationships), incorporating information from respondents who indicated these skills as being targeted without naming a specific program. Any responses detailing programs addressing physical wellbeing, or numeracy or literacy, rather than mental health and wellbeing, were not analysed further.

Health Promotion Frameworks

Information on the adoption of health promotion frameworks was compiled from the check-box and free-text sections for descriptive reporting.

Results

Survey responses were received from 598 (86.8%) of the 689 school principals invited to participate. The representativeness of this sample of schools on a range of sociodemographic indices relative to all 2,371 primary schools in NSW has been demonstrated previously (Dix et al., 2019). Two thirds of principal respondents (66.9%; n = 400) were from government schools. Schools were located predominantly in metropolitan (63.4%; n = 379) or regional (35.3%; n = 211) rather than remote (1.3%; n = 8) areas. On average, 48.9% of students within these schools were girls, 9.2% of Indigenous status, and 23.7% from a language background other than English. Based on schools’ ICSEA scores, 29.3% of children in participating schools were in the lowest quartile of socio-educational advantage and 22.3% in the highest quartile. Mean survey response time was 10.7 min. Survey responses regarding programs from one principal were all missing, yielding a final sample of 597 respondents for the present study.

Programs Selected from the Programs Menu

The principals of 442 schools (74.0%) reported delivery of at least one of the programs listed in the program menu, comprising a total of 68 programs (Dix et al., 2020, provides citations for these programs, where publicly available). Multiple programs were delivered (two in 21.1% of schools, three in 17.3%, four in 6.9%, and five in 5.2%) in the majority of these 442 schools (n = 301, 50.4%), with a single program delivered in 141 (23.6%) schools. These programs are grouped in Table 2 according to the health-promoting component addressed by the program, along with detail on the number (and percentage) of schools delivering each program, the mean number of years each program had been in use, the mean reported effectiveness of the program, and the stages (grade levels) targeted by the program.

In 2.8% (n = 17) of schools, principals reported the delivery of a program in each of the four health-promoting components, 16.1% (n = 96) of principals reported programs in three of the four components, 28.6% (n = 171) programs in two components, and 26.3% (n = 158) in a single component only. The analysis of school demographics in relation to the delivered programs in each component were all non-significant: that is, on the four demographic variables considered (socio-educational advantage, school location, size, and number of full-time equivalent teaching staff), schools delivering programs in the four components did not differ systematically from schools that did not deliver those programs.

Positive School Community (Component 1)

Almost one third of schools (n = 195; 32.7%) delivered programming identified in the Programs Guide as supporting the development of a positive school community though building respectful relationships and a sense of belonging and inclusion. Most programs were targeted to students at all or most stages (grades). On average, principals reported that delivery of these programs had been in place for between four and five years (M = 4.3 years), and that they were moderately effective (M = 2.2; with effectiveness ratings distributed as: 0% not at all, 17.7% somewhat, 45.3% moderately, and 37.0% extremely).

One-fifth (19.4%) of principals reported delivery of the Peer Support Program by Peer Support Australia, for which the review by Dix et al. (2020) indicated an evidence rating of high. This program had, on average, been in use in schools for more than five years and been targeted to students at all or most stages, with a mean effectiveness rating by principals between moderately and extremely effective (M = 2.3). As shown in Table 2, 13 of the 18 reported programs in this component were delivered in fewer than five schools, with most of those programs (10) delivered in individual schools only. For the other four most commonly reported programs in this component, the Dix et al. (2020) review indicated an evidence rating of high for the Friendly Schools and Families (i.e., Friendly Schools Plus) program, but a rating of low for the Better Buddies, Bully Busters, and Peer Mediation programs. Overall for this component, about two-thirds (64.5%) of the programs delivered had at least one published study or report on the program’s impact on behavioural outcomes.

Social-Emotional Learning (Component 2)

Almost two-thirds (n = 358; 60.0%) of principals reported the delivery of programs providing formal teaching and practice of social and emotional competencies, using the 39 programs listed in Table 2 and detailed further in Table 3. As with Component 1, most of these SEL programs were targeted to students at all or most stages/grades. On average, principals reported that delivery of SEL programs had been in place for between three and four years (M = 3.6), and that they were moderately effective (M = 2.1; with effectiveness ratings distributed as: 0.4% not at all, 22.4% somewhat, 48.1% moderately, and 29.1% extremely).

The most widely used program, delivered in one quarter of schools surveyed (n = 148), was Bounce Back!, which was rated by Dix et al. (2020) as having moderate evidence. Overall, one third of the SEL programs delivered across the surveyed schools (33.6%; 191 of 569 programs) were programs for which there is low evidence (or lack of evidence) of effectiveness (Dix et al., 2020). Further, little more than half of the 569 programs delivered (57.2%; n = 326) included the recommended series of formally structured sessions with comprehensive instructions (i.e., detailed facilitator notes, examples, responses, etc.) to ensure consistent implementation (Littlefield et al., 2017). Similarly, little more than half (58.9%; n = 335) delivered consistent opportunities for guided in-lesson skill practice for at least four of the five CASEL competencies (self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, social management, and responsible decision making).

Working with Parents and Carers of Children (Component 3)

Just over one quarter of principals (n = 170; 28.5%) reported delivering programs to engage parents and carers in bolstering children’s mental health and wellbeing, including programs providing support and information about parenting, children’s development, and mental health. On average, these programs had been offered over a period of three to four years (M = 3.8), again typically to students across all or most stages, and were considered by principals to be moderately effective (M = 2.1; with effectiveness ratings distributed as: 1.6% not at all, 24.2% somewhat, 38.2% moderately, and 36.0% extremely). The most common program delivered, in one sixth of schools, was Seasons for Growth, for which Dix et al. (2020) indicated low evidence available for the parent component (though a high evidence rating is available for the associated children and young people’s component of this program). The next two most commonly used programs, 1–2–3 Magic and Emotion Coaching Program and the Triple P parenting programs, had high evidence ratings (Dix et al., 2020). The remaining 12 programs reported by principals were each delivered in fewer than 10 schools, with variable quality of evidence available in support of program effectiveness (Dix et al., 2020). Overall for this component, just over two-fifths (41.5%) of the programs delivered had at least one published study or report on the program’s impact on behavioural outcomes.

Supporting Children at Risk of or Experiencing Mental Health Difficulties (Component 4)

Fewer than one quarter of principals (n = 135; 22.6%) reported using a recognised program targeting students with emotional, social, and/or behavioural problems. On average, these programs had been delivered for three years (M = 3.1), with variability across schools in the stage targeted by the programs. Principals perceived the programs to be less than moderately effective on average (M = 1.9; with effectiveness ratings distributed as: 0.8% not at all, 28.2% somewhat, 53.4% moderately, and 17.6% extremely). The most common program delivered, in one tenth of schools, was the school-based version of the Cool Kids program targeting worries and anxiety (internalising problems), for which a medium evidence rating was assigned (Dix et al., 2020). A high evidence rating was associated with the FRIENDS for Life program for anxiety problems delivered in 24 schools, but only a low evidence rating for the Stop, Think, Do program targeting social, emotional, and behavioural disorders delivered in 35 schools (Dix et al., 2020). The remaining 11 programs were each delivered in fewer than 10 schools; most of these programs were supported by high quality evidence in Dix et al. (2020), though only low evidence was available for several. Overall for this component, less than one third (29.3%) of the programs delivered had at least one published study or report on the program’s impact on behavioural outcomes.

Other Programs Detailed via Free-Text Response

One third of principal respondents (36.2%; n = 216) used the free-text section of the survey instrument to provide additional information about school programming. While ten principals (1.7%) indicated that, though their school had not yet implemented any mental health promotion programs they were considering which programs were needed within their school community, another three suggested that such programs were not suited to the needs of their school (e.g., a small school which relied on student and staff relationships to monitor student mental health and resolve difficulties). Four principals indicated the presence of designated personnel (e.g., school counsellor or psychologist) available to support student mental health and wellbeing in the absence of formal programming.

In total, 113 principals (18.9%) indicated delivery of other programs that were not listed in the menu of 96 programs, and which do not appear within the Dix et al. (2020) review of around 200 school-based mental health and wellbeing programs in use in Australia. Seventy of these 113 principals (61.9%) identified programs that were obtained from a provider external to the school, 28 (24.8%) described programs developed “in-house” by the school, and insufficient information was available to classify the remaining 15 responses. Six principals reported use of a specific program delivered under a partnership between NSW Government child and adolescent mental health and education services, Getting on Track in Time—Got it! (NSW Ministry of Health, 2017); this program provided specialist mental health early intervention services for children in kindergarten to 2nd-grade with behavioural concerns and emerging conduct problems. Five principals reported supplementing program delivery with designated personnel to support student social and emotional wellbeing (e.g., police liaison officer, school chaplain). The type of programs most commonly reported by principals addressed peer support (10 principals), bullying (5 principals), resilience (5 principals), and social skills (5 principals). Where ratings of effectiveness were provided by principals for these other programs (ratings given for 42 programs, 37.2%), these were perceived as either moderately (40.5%) or extremely (59.5%) effective.

Health Promotion Frameworks

The majority of principals (85.6%) indicated the implementation of one or more health promotion frameworks within their schools, including almost two-thirds (64.8%) indicating use of two or more. These included Child Protection (implemented in 61.0% of schools), Cybersafety (49.6%), School-Wide Positive Behaviour Support/Positive Behaviour for Learning (44.4%), KidsMatter Primary (26.0%), Health Promoting Schools (16.8%) and the Dare to Lead (4.7%) frameworks. The other frameworks provided in the check-box menu – KidsMatter Early Childhood, MindMatters (pre-2014), and MindMatters (post-2013)—were not targeted to the primary schooling years, and accordingly, were each reported by fewer than 20 school principals. Almost two-thirds of principals (61.1%) reported implementing a framework that encompassed multi-tiered systems of support (Tier 1, universal; Tier 2, targeted; and Tier 3, intensive)—that is, the KidsMatter, MindMatters, and School-Wide Positive Behaviour Support/Positive Behaviour for Learning frameworks. In the free-text response section, 18 principals (3.0%) indicated the implementation of a Restorative Practice/Justice framework in their schools.

Discussion

This survey of the leadership of one quarter of NSW government and non-government primary schools in 2015 indicated that half reported delivery of two or more school-based mental health promotion programs, while a quarter reported delivering none of these programs. Almost two-thirds of the principals surveyed used programs that provided formal teaching and practice of social and emotional competencies (Component 2), while one third used programs to support development of a positive school community (Component 1). One quarter reported delivery of programs to engage parents/carers in strengthening children’s mental health and wellbeing (Component 3) and to provide targeted support for children with mental health difficulties (Component 4). Universal programs supporting a positive school community were the most established (delivered, on average, for more than four years), while targeted programs for students with mental health difficulties had been delivered for the least time (three years on average) and had the lowest effectiveness ratings by principals, generally falling just short of moderately effective. With respect to the implementation of a health promotion framework to guide program selection, more than eight in 10 principals reported using one or more frameworks (including six in 10 principals reporting use of a framework that encompassed multi-tiered systems of support); one quarter reported application of the KidsMatter Primary national mental health promotion initiative that had provided a public, online Programs Guide summarising the evidence (or lack of evidence) available regarding specific programs and resources to support program implementation.

Despite school leaders’ intentions to promote students’ mental health and wellbeing, as evidenced by the uptake of health promotion programs in a majority of schools, many leaders did not select evidence-based programs. Approximately two-thirds of the programs delivering Components 1 or 2 had some empirical evidence of effectiveness, but only two-fifths of programs in Component 3 and less than one third in Component 4 were similarly evidenced. However, it is important to note that no quality assessment of the associated empirical evidence has been conducted and the threshold for achieving a ‘high’ level of evidence in the Dix et al. (2020) study was low. Furthermore, almost half of the SEL programs delivered (Component 2) lacked the recommended series of formally structured sessions with comprehensive implementation instructions and consistent opportunities for guided in-lesson skill practice of the CASEL competencies (self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, social management, and responsible decision making). These findings indicate that when detail regarding the evidence-base for programs is publicly available, school leadership may be unaware of this information or may not prioritise it in their decision-making process. Indeed, factors such as cost, popularity, and fit may be given greater consideration, particularly in light of the lack of consistent high-quality evidence against which to benchmark program options. Svane et al., (2019, p. 213) describe schools as taking “a hit and miss approach to wellbeing”, with the lack of program evaluation eroding capacity to develop an understanding of effective strategies for promoting wellbeing in schools. Determining how best to support educators in program identification and selection is critical, with qualitative research needed into why they select the programs they do and the extent to which they value robust empirical evidence as a key consideration in their program selection. Prior research in professional fields such as education and social work suggests that the type of evidence typically made available to practitioners through government or public health and education sources may not be the only sort they value, and that a range of evidence, including that which testifies to feasibility of practical implementation, is necessary to support professional judgement of contextual validity (Gleeson et al., 2020; Mockler & Stacey, 2020).

Notwithstanding the lack of existing evidence available for many of the programs delivered, responding principals nonetheless generally perceived the programs to have been at least moderately effective. The SSPESH instrument did not explicate any criteria regarding how principals should assign their effectiveness rating according to the four response levels specified, and these perceptions should not be interpreted as reliable and valid evaluations of effectiveness. Indeed, it is unclear how school leaders are monitoring program outcomes and evaluating effectiveness, beyond anecdotal evidence from staff and students (McFadden & Williams, 2020). Within Implementation Science, evaluation frameworks provide a structure for appraising implementation endeavours (Nilsen, 2015). For example, Proctor and colleagues (Proctor et al., 2011) propose a framework encompassing evaluation of acceptability, adoption (uptake), appropriateness, costs, feasibility, fidelity, penetration (integration within the setting), and sustainability. Embedding quality monitoring systems as part of the program design and delivery needs to become a mainstay in Australia. Program developers are well positioned to offer school personnel simple tools to monitor engagement and impact as part of their program, and principals should prioritise such features during program selection. Such an approach would provide invaluable operational data to support formal program evaluations and justification for ongoing funding.

While the aim of school-based management and decentralisation of decision-making has been to increase principals’ power to make contextually relevant decisions in and for their schools, it has also significantly increased administrative load (Heffernan, 2018), reducing capacity for the increasingly intensive work associated with evidence evaluation, program selection, and evaluation of effectiveness. This is an important consideration, given recommendations emerging from the Australian Government’s 2020 Productivity Commission Report on the Inquiry on Mental Health that student social-emotional health and wellbeing should be elevated in the National School Reform Agreement to “an even footing with academic progress and student engagement as an important goal that schools across all sectors of the education system must work towards, and report on their progress” [p. 19; (Productivity Commission, 2020)]. Several strategies, in addition to dedicated additional funding of $150 million per year nationally, were offered in the Inquiry Report (Productivity Commission, 2020) to achieve improved student mental health outcomes, including the requirement for all schools to develop clear leadership and accountability structures (e.g., a dedicated wellbeing leader or team) to support whole-of-school strategies, as well as clear strategies to support individual students and their families, and build links with services in the local community. The report further recommended (pp. 19–20) that: nationally consistent wellbeing measurement be rolled out across all schools; principals be held accountable for annual reporting on outcomes and improvement over time; data collected should contribute to an evidence base for future interventions; and extensive evaluation should be conducted of the policies and processes that schools put in place to support their students.

The current and potential future pressures on school leaders make the accurate provision and accessibility of rigorous evidence on school-based mental health programs even more critical. This alone, however, is not enough, for our research indicates that information is being provided with inadequate corresponding information as to the effectiveness of various programs and, also, that principals are not always choosing programs for which there is such information available. Subsequent to this survey in 2015, the NSW Department of Education developed resources to guide NSW government schools in the selection of evidence-based mental health and wellbeing programs (NSW Department of Education, 2021); having only recently (in 2020) been made available to schools, the outcomes of this guidance are not yet known, and will be specific to NSW public schools. A national approach that explicitly engages educators and school leaders to ensure that ensuing resources, programs, and policies are both evidence-based and flexible enough to meet the needs of schools may help mitigate fragmentation of policies and resources across jurisdictions and education sectors. We argue that this need is not being met by the most recent national initiative to support student mental health and wellbeing, Be You (Australian Government, 2021), which as of May 2021 provided evidence of effectiveness ratings for only a limited subset (~ 40) of programs for which the program providers applied to be listed in the current Programs Directory. The new Australian Education Research Organisation (AERO), emerging from the 2017 Review to Achieve Educational Excellence in Australian Schools chaired by David Gonski (Gonski et al., 2018), might assist in providing a more comprehensive source of evidence-based programs and information for principals and teachers. This, together with the commissioning of SEL programs and multi-tiered systems of support implementation trials, could better enable educators to engage with the intentions of Australian Curriculum’s Personal and Social Capability.

Alongside this, extensive work remains to be done to strengthen the evidence base on school-based mental health programs and their implementation. Further work is especially needed to improve the quality of evidence supporting program effectiveness. The effectiveness of any program in a particular school context will be influenced by factors such as dosage (i.e., the frequency and length of program delivery), fidelity (i.e., how closely the implementation adheres to the intervention manual), and quality of delivery (i.e., by qualified, experienced staff). Though school leaders may be motivated to address what they perceive as the unique needs of their community through adaptations to programs, rigorous effectiveness trials of established programs are required to identify the ‘active’ crucial components of successful programs that must be implemented with fidelity (Littlefield et al., 2017), as well as to determine their applicability to subgroups of students and cultural contexts (Collie et al., 2017). We highlight the utility of multi-level partnership models, such as promoting school-community-university partnerships to enhance resilience (PROSPER) in the US, to support high quality implementation and long-term sustainability of prevention programs (Nordstrum et al., 2017). This model incorporates three tiers, with local community strategic teams (extension educators and school personnel who deliver the program) provided with sustained, solution-focused and proactive assistance from state level teams (university-based prevention specialists and resources that support the translation of scientific theory and evidence into user-friendly interventions) via an intermediate-level prevention coordinator. This coordinator functions as a liaison between the university prevention team and local teams, providing the knowledge, skills, motivation, and technical assistance required for effective implementation of the program. This collaborative and dynamic approach provides important capacity to engage in a continuous evaluation and improvement process, where the program may be effectively adapted and aligned with a unique school context while maintaining fidelity to the program goals (Nordstrum et al., 2017; Redding et al., 2017). Capacity for such adaptions and alignments to local contexts are pertinent in multi-cultural Australian society, and in the context of geographic variation from large metropolitan schools to single-teacher remote schools.

Educators and school systems also require appropriate support and engagement from local mental health and social services agencies to meet the diverse needs of their school community. Previous work with this sample of NSW government and non-government schools identified that leaders perceived engaging and working effectively with parents/carers in supporting student mental health and wellbeing as the most challenging of the four components for schools to implement (Dix et al., 2019). The present study further indicated that the programs principals selected to engage parents/carers (Component 3) and support students at risk of or experiencing mental health difficulties (Component 4) had the least available evidence supporting their effectiveness, despite the availability of programs with high levels of evidence. Further embedding of multi-tiered systems of support within the school community is needed to provide a continuum of support for all students, spanning universal prevention for all, targeted interventions to improve the social, emotional, and behavioural skills of at-risk students who need additional support, as well as individualised intensive supports for students experiencing ongoing mental health and academic difficulties. Strong relationships and communication lines, and greater program integration between education, mental health, and social services agencies might assist schools in facilitating and coordinating better provision of universal and targeted interventions for students between the school and local community (American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on School Health, 2004).

Study Limitations

The present study was limited to school-based mental health and wellbeing programs delivered to primary school students in a single Australian state (NSW), and may not be generalisable to other educational jurisdictions within Australia (or elsewhere), nor to the secondary (middle/high) school context. Though our sample of schools were representative of NSW primary schools according to a range of sociodemographic indices (government vs. non-government, geographical location, socioeconomic profile, and proportions of Indigenous and female students, and students with a language background other than English; Dix et al., 2019), we had no means of ascertaining whether the principals who elected to participate were predisposed to prioritising mental-health and thus more likely to implement school-based programs.

This quantitative study also did not directly assess principals’ decision-making processes in relation to selecting programs for their school community, which might be usefully explored using qualitative methods. For example, exploring whether principals sought a program to meet government-mandated curriculum requirements, selected a program in response to an identified need, and/or engaged with external partners to select and implement programs and to monitor their effectiveness, are priority questions for research. Future studies might likewise examine how principal characteristics (such as age, gender, and experience) may relate to their decisions to implement school-based mental health and wellbeing programs, particularly those engaging the parent community, and to their perceptions of program effectiveness.

The study presents a snapshot of school-based practice up to 2015 only and does not capture programs implemented subsequently. Although data were obtained from principals regarding their own perception of program effectiveness, no formal measurement of the frequency, fidelity, and quality of program implementation was attempted. Instead, the study contextualised the programs being delivered using ratings of program effectiveness derived from a recent review of more than 200 school-based wellbeing programs delivered in Australia as of August 2020 (Dix et al., 2020), extending the effectiveness information originally compiled for the KidsMatter Primary Programs Guide.

The study was further limited in relying on a sole report (typically by the school principal) and might have identified additional programs or captured alternative perceptions of program effectiveness within the school if a broader consultation with school personnel was undertaken. Similarly, the limited sampling of remote schools (n = 8) means that study findings reflect predominantly the perceptions of principals leading metropolitan and regional primary schools. Further research to characterise the experience of remote school principals is merited.

Conclusion

The present study indicates that, though a majority of school leaders had implemented school-based mental health and wellbeing programs in their schools, most often via formal teaching and practice of social and emotional competencies (a requirement of the Australian Curriculum), a quarter of school leaders had not. Moreover, many leaders selected programs for which evidence of effectiveness was poor or absent. Further work is needed to support a national approach to strengthening the evidence on school-based mental health and wellbeing programs and their implementation, including the adoption of multi-tiered systems of support that encompass universal prevention for all students, targeted interventions to improve the social, emotional, and behavioural skills of at-risk students who need additional support, and individualised intensive supports for students experiencing ongoing mental health and learning difficulties. Until we do so, efforts taken to build mentally healthy learning communities Australia-wide will be inconsistent.

Data availability

The Survey of School Promotion of Emotional and Social Health (SSPESH) data is owned by the University of New South Wales. Researchers interested in using the SSPESH data in collaboration with New South Wales Child Development Study (NSW-CDS) investigators should contact A/Prof. Kristin Laurens (kristin.laurens@qut.edu.au; kristin.laurens@unsw.edu.au) and NSW-CDS Scientific Director Prof. Melissa Green (melissa.green@unsw.edu.au) with their expressions of interest.

Notes

Universal programs are non-targeted and often school-wide interventions that do not require students to meet specific eligibility criteria. They reflect a preventive approach with an emphasis on equipping students with the skills they need to become resilient and on supporting their wellbeing.

References

ACARA. (2020). Australian Curriculum: Personal and Social Capability. Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA). https://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/f-10-curriculum/general-capabilities/personal-and-social-capability/

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on School Health. (2004). School-based mental health services. Pediatrics, 113(6), 1839. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.113.6.1839

Australian Government. (2021). be you. https://beyou.edu.au/

Bowles, T., Jimerson, S., Haddock, A., Nolan, J., Jablonski, S., Czub, M., & Coelho, V. (2017). A review of the provision of social and emotional learning in Australia, the United States, Poland, and Portugal. Journal of Relationships Research. https://doi.org/10.1017/jrr.2017.16

Carr, V. J., Harris, F., Raudino, A., Luo, L., Kariuki, M., Liu, E., Tzoumakis, S., Smith, M., Holbrook, A., Bore, M., Brinkman, S., Lenroot, R., Dix, K., Dean, K., Laurens, K. R., & Green, M. J. (2016). New South Wales Child Development Study (NSW-CDS): An Australian multiagency, multigenerational, longitudinal record linkage study. BMJ Open, 6(2), e009023. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009023

CASEL. (2013). 2013 CASEL guide: Effective social and emotional learning programs—Preschool and elementary school edition. Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning. https://casel.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/2013-casel-guide.pdf

Collie, R. J., Martin, A. J., & Frydenberg, E. (2017). Social and emotional learning: a brief overview and issues relevant to Australia and the Asia-Pacific. In E. Frydenberg, A. J. Martin, & R. J. Collie (Eds.), Social and Emotional Learning in Australia and the Asia-Pacific: Perspectives, Programs and Approaches (pp. 1–13). Springer Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-3394-0_1

Dix, K. L., Green, M. J., Tzoumakis, S., Dean, K., Harris, F., Carr, V. J., & Laurens, K. R. (2019). The Survey of School Promotion of Emotional and Social Health (SSPESH): A Brief Measure of the Implementation of Whole-School Mental Health Promotion. School Mental Health, 11(2), 294–308. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-018-9280-5

Dix, K. L., Kashfee, S. A., Carslake, T., Sniedze-Gregory, S., O'Grady, E., & Trevitt, J. (2020). A systematic review of intervention research examining effective student wellbeing in schools and their academic outcomes. Addendum: Wellbeing Programs in Australia. Evidence for Learning. https://evidenceforlearning.org.au/assets/Uploads/Addendum-Student-Health-and-Wellbeing-Systematic-Review-FINAL-25-Sep-2020.pdf

Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D., & Schellinger, K. B. (2011). The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Development, 82(1), 405–432. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01564.x

Early Intervention Foundation. (2014). Early Intervention Foundation Guidebook. Retrieved 22 January, 2020 from https://guidebook.eif.org.uk/

Education Council. (2019). Alice Springs (Mparntwe) Education Declaration. Education Council. http://www.educationcouncil.edu.au/site/DefaultSite/filesystem/documents/Reports%20and%20publications/Alice%20Springs%20(Mparntwe)%20Education%20Declaration.pdf

Elliott, S. N., Frey, J. R., & Davies, M. (2015). Systems for assessing and improving students’ social skills to achieve academic competence. In J. A. Durlak, C. E. Domitrovich, R. P. Weissberg, & T. P. Gullotta (Eds.), Handbook of social and emotional learning: Research and practice (pp. 301–319). The Guilford Press.

Fixsen, D., Blase, K., Metz, A., & Van Dyke, M. (2015). Implementation Science. In J. D. Wright (Ed.), International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences (Second Edition) (pp. 695–702). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.10548-3

Gilbert, R. (2019). General capabilities in the Australian curriculum: Promise, problems and prospects. Curriculum Perspectives, 39(2), 169–177. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41297-019-00079-z

Gleeson, J., Walsh, L., Rickinson, M., Kirkby, J., O’Donovan, R., & Grimmett, H. (2020). Challenges and Opportunities of Evidence Use in Practice in Australian Children’s Development Programs. Journal of Evidence-Based Social Work, 17(5), 593–610. https://doi.org/10.1080/26408066.2020.1781727

Gonski, D., Arcus, T., Boston, K., Gould, V., Johnson, W., O'Brien, L., Perry, L.-A., & Roberts, M. (2018). Through Growth to Achievement. Report of the Review to Achieve Educational Excellence in Australian Schools. Commonwealth of Australia. https://www.education.gov.au/educationalexcellencereview

Graetz, B., Littlefield, L., Trinder, M., Dobia, B., Souter, M., Champion, C., Boucher, S., Killick-Moran, C., & Cummins, R. (2008). kidsmatter: a population health model to support student mental health and well-being in primary schools. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 10(4), 13–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623730.2008.9721772

Green, M. J., Harris, F., Laurens, K. R., Kariuki, M., Tzoumakis, S., Dean, K., Islam, F., Rossen, L., Whitten, T., Smith, M., Holbrook, A., Bore, M., Brinkman, S., Chilvers, M., Sprague, T., Stevens, R., & Carr, V. J. (2018). Cohort Profile: The New South Wales Child Development Study (NSW-CDS)- Wave 2 (child age 13 years). International Journal of Epidemiology, 47(5), 1396–1397k. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyy115

Grove, C., & Laletas, S. (2020). Promoting student wellbeing and mental health through social and emotional learning. In L. J. Graham (Ed.), Inclusive Education for the 21st Century: Theory, Policy and Practice (pp. 317–335). Routledge.

Heffernan, A. (2018). Power and the ‘autonomous’ principal: Autonomy, teacher development, and school leaders’ work. Journal of Educational Administration and History, 50(4), 379–396. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220620.2018.1518318

Humphrey, N. (2013). Social and Emotional Learning: A Critical Appraisal. SAGE Publications Ltd.

Laurens, K. R., Tzoumakis, S., Dean, K., Brinkman, S. A., Bore, M., Lenroot, R. K., Smith, M., Holbrook, A., Robinson, K. M., Stevens, R., Harris, F., Carr, V. J., & Green, M. J. (2017). The 2015 Middle Childhood Survey (MCS) of mental health and well-being at age 11 years in an Australian population cohort. BMJ Open, 7(6), e016244. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016244

Littlefield, L., Cavanagh, S., Knapp, R., & O’Grady, L. (2017). KidsMatter: Building the Capacity of Australian Primary Schools and Early Childhood Services to Foster Children’s Social and Emotional Skills and Promote Children’s Mental Health. In E. Frydenberg, A. J. Martin, & R. J. Collie (Eds.), Social and Emotional Learning in Australia and the Asia-Pacific: Perspectives, Programs and Approaches (pp. 293–311). Springer Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-3394-0_16

MCEETYA. (2008). Melbourne Declaration on Educational Goals for Young Australians. Ministerial Council on Education, Employment, Training and Youth Affairs. http://www.curriculum.edu.au/verve/_resources/National_Declaration_on_the_Educational_Goals_for_Young_Australians.pdf

McFadden, A., & Williams, K. E. (2020). Teachers as evaluators: Results from a systematic literature review. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 64, 100830. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2019.100830

Meyers, D. C., Domitrovich, C. E., Dissi, R., Trejo, J., & Greenberg, M. T. (2019). Supporting systemic social and emotional learning with a schoolwide implementation model. Evaluation and Program Planning, 73, 53–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2018.11.005

Mockler, N., & Stacey, M. (2020). Evidence of teaching practice in an age of accountability: When what can be counted isn’t all that counts. Oxford Review of Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2020.1822794

Nilsen, P. (2015). Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implementation Science, 10, 53. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-015-0242-0

Nordstrum, L. E., LeMahieu, P. G., & Berrena, E. (2017). Implementation science: Understanding and finding solutions to variation in program implementation. Quality Assurance in Education, 25(1), 58–73. https://doi.org/10.1108/QAE-12-2016-0080

NSW Ministry of Health. (2017). Getting On Track In Time—Got It! Program delivery implementation guidelines https://www.health.nsw.gov.au/mentalhealth/resources/Publications/got-it-guidelines.pdf

NSW Department of Education. (2021). Evidence-based mental health and wellbeing programs for schools. https://education.nsw.gov.au/student-wellbeing/counselling-and-psychology-services/mental-health-programs-and-partnerships/evidence-based-mental-health-wellbeing-programs-for-schools.

Powell, M. A., & Graham, A. (2017). Wellbeing in schools: Examining the policy–practice nexus. The Australian Educational Researcher, 44(2), 213–231. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-016-0222-7

Proctor, E., Silmere, H., Raghavan, R., Hovmand, P., Aarons, G., Bunger, A., Griffey, R., & Hensley, M. (2011). Outcomes for implementation research: Conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 38(2), 65–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7

Productivity Commission. (2020). Mental Health, Inquiry Report. Commonwealth of Australia. https://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/mental-health/report/mental-health.pdf

Redding, C., Cannata, M., & Haynes, K. T. J. P. J. (2017). With scale in mind: A continuous improvement model for implementation. Peabody Journal of Education, 92, 589–608.

Slee, P. T., Lawson, M. J., Russell, A., Askell-Williams, H., Dix, K. L., Owens, L., Skrzypiec, G., & Spears, B. (2009). KidsMatter Primary Evaluation Final Report. Centre for Analysis of Educational Futures, Flinders University of South Australia. http://hdl.handle.net/2328/26832

Stoiber, K., & Gettinger, M. (2016). Multi-Tiered Systems of Support and Evidence-Based Practices. In S. Jimerson, M. Burns, & A. VanDerHeyden (Eds.), Handbook of Response to Intervention. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-7568-3_9

Svane, D., Evans, N., & Carter, M.-A. (2019). Wicked wellbeing: Examining the disconnect between the rhetoric and reality of wellbeing interventions in schools. Australian Journal of Education, 63(2), 209–231. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004944119843144

Taylor, R. D., Oberle, E., Durlak, J. A., & Weissberg, R. P. (2017). Promoting positive youth development through school-based social and emotional learning interventions: a meta-analysis of follow-up effects. Child Development, 88(4), 1156–1171. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12864

Weissberg, R. P., Durlak, J. A., Domitrovich, C. E., & Gullotta, T. P. (2015). Social and emotional learning: Past, present, and future. In J. A. Durlak, R. P. Weissberg, & T. P. Gullotta (Eds.), Handbook of social and emotional learning: Research and practice (pp. 3–19). The Guilford Press.

Wyn, J. (2007). Learning to ‘become somebody well’: Challenges for educational policy. The Australian Educational Researcher, 34(3), 35–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03216864

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge support provided for the administration of the Survey of School Promotion of Emotional and Social Health (SSPESH) by the NSW Department of Education (represented by Robert Stevens, Susan Harriman, and Liliana Ructtinger), the Catholic Education Commission NSW (represented by Peter Grace), the Association of Independent Schools of NSW (represented by Robyn Yates and Susan Wright), and other stakeholder organisations including the NSW Primary Principals’ Association, NSW Teachers Federation, Independent Education Union NSW/ACT, Federation of Parents and Citizens Associations of NSW, Council of Catholic School Parents, NSW Parents’ Council, Isolated Children’s Parents’ Association, and the NSW Aboriginal Education Consultative Group. The authors also acknowledge the contributions of present and past members of the NSW-CDS Scientific Committee who oversee the project (http://nsw-cds.com.au/); and the staff and professional colleagues who supported SSPESH administration and/or data assembly or interpretation: Kate Tillack, Stephanie Dick, Luke Duffy, Philip Hull, Luming Luo, Brooke McIntyre, Alessandra Raudino, Stephen Lynn, and Claire Essery. The authors thank Principals Australia Institute for provision of the online survey. The information and perspectives expressed in the manuscript do not necessarily reflect the views of these contributing organisations or individuals.

Funding

This research was supported by funding from a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Project Grant (1058652), an Australian Research Council (ARC) Linkage Project (LP110100150, with the NSW Ministry of Health, NSW Department of Education, and the NSW Department of Community and Justice representing the Linkage Project Partners), an Australian Rotary Health Mental Health for Young Australians Research Grant (104090), and an ARC Future Fellowship awarded to KRL (FT170100294).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

In line with the ICMJE authorship guidelines, KRL, KLD, FH, ST, VJC, and MJG made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work, and to the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the data. KRL, LJG, KLD, FH, ST, KEW, JMS, TP, NW, MT, VJC, and MJG contributed to the drafting of the manuscript and/or to revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. KRL, LJG, KLD, FH, ST, KEW, JMS, TP, NW, MT, VJC, and MJG have given final approval of the version to be published, and agree to its accuracy.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethics approval

Ethical review of the study was provided by the University of NSW Human Research Ethics Advisory Panel D (Reference number: HC14348) and the NSW Department of Education’s State Education Research Approvals Process (SERAP reference number: 2015083), in accordance with the National Statement on Ethical Conduct of Human Research, including associated Guidelines approved under Sect. 95A of the Privacy Act 1988 relevant to Catholic and Independent schools, and Sect. 41 of the Privacy and Personal Information Protection Act 1998 relevant to NSW public schools.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. Information was gathered by identification code, and respondents were not personally identified with their responses.

Consent for publication

Informed consent for the publication of survey data in aggregated form (i.e., preventing identification of any individual school or respondent) was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Laurens, K.R., Graham, L.J., Dix, K.L. et al. School-Based Mental Health Promotion and Early Intervention Programs in New South Wales, Australia: Mapping Practice to Policy and Evidence. School Mental Health 14, 582–597 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-021-09482-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-021-09482-2