Abstract

This study explored associations between peer victimization experiences and adolescents’ perceptions of life satisfaction. Public high school students (n = 1,325) completed a self-report questionnaire measuring being bullied and life satisfaction. Multiple logistic regression analyses were conducted to examine the relationships between being bullied and perceived life satisfaction across four race and gender groups. Results indicated that significant associations (p ≤ .05) were established for reduced life satisfaction and being bullied over the past 12 months due to religion for whites and black males (OR = 3.18–4.84); victimization due to gender for black males and white females (OR = 3.07–4.52); victimization for race/ethnicity for whites and black females (OR = 2.46–3.88); victimization for sexual orientation for males (OR = 3.42–4.51) and victimization for a disability for all four race/gender groups (OR = 2.92–7.35). Results suggest that perceived life satisfaction is related to a variety of differentially motivated victimization experiences, but not uniformly across race and gender groups. Implications for the delivery of race- and gender- specific prevention interventions are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Enhancing quality of life (QOL) is the cornerstone of health promotion efforts seeking to empower individuals to improve their overall health (Epp 1986; Raphael 1996). Research integrating these two areas has been limited, particularly with adolescents, although some noteworthy efforts have appeared (Huebner et al. 2004a, b; Proctor et al. 2008; Renwick et al. 1996). QOL research has been conceptualized as objective or subjective. The objective QOL perspective has been characterized by a focus on differences in external conditions of life, such as income levels, housing quality, and access to recreational services. In contrast, the subjective perspective has been characterized by a focus on differences in internal conditions, such as individuals’ life satisfaction reports, that is, their subjective evaluations of the quality of their lives. Subjective QOL research includes, but is not limited to, a person’s life satisfaction judgments with respect to their overall lives and/or specific domains (Diener et al. 1999). This research considers the USA high school students’ life satisfaction and its relationship with various types of peer- victimization experiences.

Despite variations in socioeconomic and cultural backgrounds, there are commonalities in adolescent developmental experiences. Characterized by conspicuous physical, mental, and emotional changes, adolescence is a critical period in psychological development. In particular, the psychosocial development of adolescents can be heavily influenced by peer group experiences (Jessor 1993).

Adolescent peer groups are frequently involved in bullying or victimization. School bullying has been identified as a problematic behavior among adolescents affecting academic achievement, prosocial skills and psychological well-being for both victims and perpetrators (Boulton et al. 2008; Hawker and Boulton 2000; Roland 2002). Bullying is usually defined as a specific form of aggression, which is intentional, repeated, and involves a disparity of power between the victim and the perpetrator(s) (Olweus 1993).

The prevalence of peer victimization in the USA is significant as a recent study of USA adolescents found prevalence rates of having been bullied at school at least once in the past 2 months were 20.8% physically, 53.6% verbally, 51.4% socially or 13.6% electronically (Wang et al. 2009). African–American adolescents report being bullied less frequently than White or Hispanic youth (Carlyle and Steinman 2007; Wang et al. 2009). Gay and lesbian youth are more likely to be bullied than heterosexual adolescents (Berlan et al. 2010). Special needs students are at increased likelihood peer victimization (Thompson et al. 2007). Additionally, males are more likely to be involved in bullying than females (Craig et al. 2009; Haynie et al. 2001). Bullying behavior has a tendency to peak in early adolescence and decrease in frequency as adolescence progresses (Eisenberg and Aalsma 2005).

Peer victimization in adolescence has been related to a variety of measures of psychopathology (Due et al. 2005; Fekkes et al. 2006; Van der Wall et al. 2003). Specifically, the experience of peer victimization has been linked to increased psychological stress, psychosomatic illness, depression, anxiety, poor physical health, lower self-esteem and suicide ideation (Due et al. 2005; Fekkes et al. 2006; Eisenberg et al. 2003; Saluja et al. 2007; Menesini et al. 2009; Park et al. 2006). Few studies have investigated linkages between peer victimization and life satisfaction among adolescents.

The distinction between life satisfaction and measures of psychopathology is important because life satisfaction measures have been found to be related to, but distinct from, traditional measures of psychopathology (Diener et al. 1999; Greenspoon and Saklofske 1997; Huebner 2004; Suldo and Shaffer 2008). Research on life satisfaction has supported the positive psychology orientation that defines mental health—as more than the absence of psychopathological symptoms (Huebner et al. 2006; Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi 2000). Specifically, life satisfaction is a broad construct with a wide network of correlates, which shows discriminant validity in relation to measures of psychopathology. For example, although measures of life satisfaction and depression are moderately correlated, general or overall life satisfaction is distinguishable from depression in that it shows different correlates (e.g., gender) and appears to be a prodromal indicator of depression, showing decreases before clinical levels of depression become apparent (Lewinsohn et al. 1991). Similarly, life satisfaction is distinguishable from low self-esteem (Huebner et al. 1999). Thus, an adolescent can be dissatisfied with life as a result of experiencing undesirable circumstances, yet not display symptoms of psychopathology. Similarly, an adolescent may be relatively satisfied with her or his life, but concurrently experience symptomatology (Antaramian et al. 2010; Suldo and Shaffer 2008).

Two studies have suggested linkages between quality of life and peer victimization in adolescents. Wilkins-Shurmer et al. (2003) found that being bullied was related to decreased health related quality of life in a sample of youth age 10–14 in Australia. Martin et al. (2008) also explored the relationship between life satisfaction and peer victimization experiences and found that decreased life satisfaction was significantly correlated with reported physical and relational victimization in a sample of middle school students in the Southeastern USA.

Although these studies suggest linkages between life satisfaction and victimization, there is a need for research that considers the specific nature of the linkages. For example, differences in adolescents’ life satisfaction may relate to differences in the perceived motivation for the victimization. Thus, this research examined various types of victimization experiences based on differences in the perceived motivations for the bullying (e.g., bullying based on religion, gender, race, sexual orientation and disability). Therefore, the purpose of this study was to examine the associations between selected self-reported adolescent victimization experiences and perceptions of life satisfaction among public high school students in South Carolina, USA. Such associations were investigated separately for race and gender groups (Black males; Black females; White males; and White females) given possible demographic differences in peer victimization and life satisfaction among adolescents (Huebner et al. 2000; Valois et al. 2001; Valois et al. 2003).

2 Methods

2.1 Participants

Data for this study are derived from the evaluation efforts of a federally funded (US Departments of Health & Human Services, Education and Juvenile Justice) Safe Schools/Health Students project. The overall goal of this project was to decrease substance use, violent and aggressive behaviors while increasing mental health services and improving academic performance for students in the school district.

Self-report data were collected from 1,404 9th–12th graders from three district high schools, the alternative education center, and the career education center (with the exception of students in full-time special education classes) in a rural South Carolina county, USA.

2.2 Data Collection/Instrumentation

The Health Risk Behavior Questionnaire (HRBQ) was developed by the evaluation team in conjunction with project and school district teachers and staff. It was determined at the outset that the HRBQ would satisfy self-report data collection needs for this funded project involving high school students (grades 9 through 12) in the school district. Items for this questionnaire had been utilized in previous national and state Youth Risk Behavior Survey studies and Safe Schools/Healthy Students and have been field-tested for content validity and reliability (Brener et al. 1995, 2002). The 94 item HRBQ consisted of the following sections with corresponding items: Demographics (grade, gender, ethnicity, eligibility for a free/reduced price lunch, primary adults who live in the home); Body weight and height; Hours worked at a job for pay during the school year and participation in groups, organizations or activities during the school year; Violent and aggressive behaviors (weapon carrying, physical fighting, dating violence); Depression and suicide ideation and attempted suicide; victimization; Suspension from school; Substance abuse (tobacco, alcohol use, marijuana), and other, sexual risk behaviors, Weight management behaviors; Physical activity; Decision making/impulsive behavior; Social situation confidence; and Student life satisfaction/quality of life. Each item had appropriate response options established from field studies and psychometric scaling-(Brener et al. 1995, 2002).

The “passive permission” approach for parental permission was utilized. Parent notification forms were distributed at least 5 days in advance of questionnaire administration and parents who did not want their children to participate were required to return the appropriate signed permission form. The HRQB questionnaire was anonymous (no names), voluntary in nature (a student could opt out on the day of completion) and asked only that the student respond on the scantron answer sheet with a code number to identify his/her respective school for reporting purposes. Trained data collectors conducted questionnaire administration emphasizing anonymity, privacy and confidentially. The research was approved by the referent university’s review board for the rights of human subjects in research and the school district’s review board for data collection by outside evaluators.

The evaluation team subsequently examined each of the 1,404 scantron sheets for data quality and 94% contained usable data. Of the usable data, 1,252 responses were used for analyses in this study.

2.2.1 Life-Satisfaction Instrumentation

The Brief Multidimensional Life Satisfaction Scale (BMSLSS) included in the HRBQ was based on the 6 domains (satisfaction with: family, friends, school, self, living environment, and a global item, overall life) of the Multidimensional Students’ Life Satisfaction Scale (Huebner 1994; Seligson et al. 2003). The BMSLSS has been validated for use with children/adolescents aged 8 to 18 (see Huebner et al. 2006 for a review). The BMSLSS has six items, one for each domain. The six items were “I would describe my satisfaction with my family life as”; “I would describe my satisfaction with my friendships as”; “I would describe my satisfaction with my school experience as”; “I would describe my satisfaction with myself as”; “I would describe my satisfaction with where I live as”; and a global question “I would describe my satisfaction with my overall life as.” Seven response options from the widely used Terrible-Delighted Scale were used for each of these questions: (a) terrible, (b) unhappy, (c) mostly dissatisfied, (d) mixed (equally satisfied and dissatisfied), (e) mostly satisfied, (f) pleased, and (g) delighted (Andrews and Withey 1976). The scale demonstrated acceptable internal consistency with a Cronbach’s alpha of .85.

2.2.2 Peer Victimization Instrumentation

The five self-report items on frequency of being bullied were utilized from the 2006 California Healthy Kids Survey (California Healthy Kids Survey 2006). Bully behavior items were based on a past 12 months basis and asked the participant “how many times were you harassed or bullied because of: 1) Your religion; 2) Your gender (being male or female); 3) Your race, ethnicity, or national origin; 4) Because someone thought you were gay or lesbian; and 5) Because of a physical or mental disability.” Response options for the bullying items were: 1) 0 times; 2) 1 time; 3) 2 or 3 times; 4) 4 or 5 times; 6) 6 or 7 times; 7) 8 or 9 times; 8) 10 or 11 times; and 9) 12 or more times (over the past 12 months). An additional item from the CDC YRBS was added to the HRBQ and asked, “During the past 30 days, on how many days did you not go to school (truant) because you felt you would be unsafe at school or on your way to or from school?” Response options for this item were: 1) 0 days; 2) 1 day; 3) 2 or 3 days; 4) 4 or 5 days; and 6) 6 or more days (Kolbe 1990). These items have content validity and reliability based on field testing and utilization in the California Health Schools Survey and the CDC Youth Risk Behavior Survey respectively (California Healthy Kids Survey 2006; Brener et al. 1995, 2002).

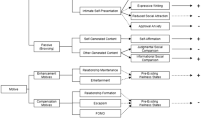

2.3 Data Analysis

Previous research utilizing correlational analysis indicated that the six variables for life satisfaction could be computed in an amalgam variable (Zullig et al. 2001; Valois et al. 2003). After pooling the global variable to five other life satisfaction variables, all six were collapsed into one quasi-continuous dependent variable ranging in score from 6 (1 × 6) to 42 (7 × 6). The life satisfaction score was registered as a mean value with lower scores indicating reduced life satisfaction and higher scores indicating increased life satisfaction. The pooled variable was divided into three outcome levels, dissatisfied, mixed, and satisfied. Mean Satisfaction Scores (MSS) ranging from 6 to 27 were classified as dissatisfied; MSS of 28–34 were mixed and MSS of 35 and higher were satisfied.

The independent variables for this study were the peer victimization variables that included: being truant from school because of a fear of bullying in the last 30 days; being bullied because of religion in the past 12 months; being bullied because of gender in the past 12 months; being bullied because of race, ethnicity, or national origin in the past 12 months; being bullied because of others perception of one’s sexual orientation in the past 12 months; and being bullied because of physical or mental disability in the past 12 months. Responses to the victimization variables were dichotomized as to whether or not adolescents had experienced any form of victimization in the past 12 months for five variables and within the past 30 days for the one variable on truancy due to fear of being bullied on the way to school or coming home from school (Table 1).

A polychotomous logistic regression analysis was performed to determine the likelihood of occurrence between variables of interest. Subjects were analyzed according to four race/gender groups; Black males, White males, Black females, and White females. Students who reported any other race/ethnic group were eliminated from the analysis because of their small numbers. Stepwise logistic regression was performed to obtain the probability of being classified as dissatisfied or at mid-range level of life-satisfaction if a student self-reported experiences of victimization. All analyses were performed using Statistical Analysis System, PC SAS 9.1.3 statistical package (Statistical Analysis System 2006).

3 Results

3.1 Description of Participants

Twelve hundred fifty two subjects were utilized for this analysis. Five hundred ninety nine (47.84%) participants in the sample were males and 653 (52.16%) were females. There was also nearly even distribution of the sample regarding race/ethnicity. Six hundred sixty two students (53.63%) self-identified as Black and 581 self-identified as White (46.37%). Three-hundred twelve males identified as Black (24.92%) and 287 as White (22.92%). Of the female population, Blacks were the highest percentage of the sample with 359 participants (28.67%). There were 294 White females thereby composing 23.48% of the sample.

3.2 Self-Reported Life Satisfaction

Reports of perceived life satisfaction were analyzed according to race and gender. Three-hundred eighty seven participants (30.91%) reported being mostly dissatisfied with their lives. Four-hundred sixty seven (37.30%) of the participants reported equal amounts of satisfaction and dissatisfaction and 392 (31.31%) described their lives as being “Mostly satisfied” to “Delighted.” Males reported greater dissatisfaction with life (n = 197, 15.74%) than females (n = 190, 15.18%).

Black females were most likely to report being equally satisfied and dissatisfied with life (n = 143, 11.42%). White females were also likely to be classified into the middle-range satisfaction group (n = 117, 9.35%) indicating that females are apt to be equally satisfied and dissatisfied with life (Table 2).

Blacks displayed the greatest satisfaction with life with 17.73% of participants classified as satisfied. Of the Black males, 103 were classified reporting being satisfied with life (8.23%). Ninety eight were categorized into the mixed range level (7.83%) and 107 were mostly dissatisfied (8.55%) (Table 2).

For White males, 6.87% (n = 86) reporting being satisfied with their lives while 7.19% (n = 90) were dissatisfied. One hundred nine (8.71%) were categorized into the mixed group (Table 2). For Black females 9.5% (n = 119) reported being satisfied with life, 7.75% (n = 97) reported equal amounts of satisfaction and dissatisfaction, and 11.42% (n = 143) were mostly dissatisfied (Table 2).

For White females 6.71% (n = 84) reported being satisfied with life, 9.35% (n = 117) reported equal amounts of satisfaction and dissatisfaction, and 7.43% (n = 93) were mostly dissatisfied (Table 2).

3.3 Self-Reported Victimization

Frequencies and percents for the victimization variables are listed in Table 1. Participants in the study reported frequent and salient victimization. A total of 5.76% (n = 72) of the public high school students in the sample reported truancy because they felt unsafe at school or on their way to and from school (Table 1).

With 116 subjects (9.27%) reporting peer victimization based on race, ethnicity, or national origin, this basis for victimization was the most prevalent in this sample. Forty White males (3.19%) reported being victimized based on race, making this subpopulation most susceptible to this form of victimization in this sample. Thirty-five (2.80%) White females reported this form of victimization as well, indicating that harassment owing to race, ethnicity or national origin was most likely to occur among Whites (Table 1).

With 7.51% (n = 94) of the sample reporting being victimized based on gender, this was the second most common cause for victimization. Females were most likely to experience this form of harassment or bullying with 31 (2.48%) Black females and 35 (2.80%) White females reporting being victimized based on gender (Table 1).

Blacks were most likely to have been truant from school because they wanted to avoid being victimized. A reported 23 (1.84%) Black males and 21 (1.68%) Black females reported missing school to avoid being victimized by their peers (Table 1).

The third most common cause for victimization was based on sexual orientation (n = 85). Whites females were most likely to report being victimized based on sexual orientation (n = 31, 2.48%). Black males were least likely to be harassed or bullied because of sexual orientation (n = 13, 1.04%). Black females and White males were almost equally likely to report sexual orientation as the basis of victimization (n = 21, 1.68% and n = 20, 1.60% respectively) (Table 1).

There were 66 students who reported being victimized on the basis of physical or mental disability (Table 1). Black females and White males reported similar levels of being victimized (n = 20, 1.60% and n = 19, 1.52% respectively). White females and Black males also reported similar levels of experience with physical or mental disability as a basis for harassment or bullying (n = 14, 1.12% and n = 13, 1.04% respectively) (Table 1).

Victimization based on religion was the least likely to be reported in this sample (n = 58). White males and females were most likely to report victimization on this basis. There were 18 (1.44%) White males that reported this and 16 White females (1.28%). Eleven (0.88%) Black males and 13 (1.04%) Black females reported experiencing harassment or bullying based on religion (Table 1).

3.4 Mid-Range Adolescent Life Satisfaction and Bulling Behavior

A significant protective relationship was found for Black males between having mid-range feelings of life satisfaction and being truant from school in the past 30 days because of peer victimization (OR = .17). Being truant because one was victimized appears to have a protective effect. If odds-ratios are less than 1, then the risk in exposed persons is less than that of non-exposed. Black males who were truant were .17 times less likely to report mid-range feelings of life-satisfaction than those who were not truant.

In addition, significant protective relationships were established for White females who were at the mid-range level of life satisfaction and were victimized because of gender, race, ethnicity, national origin, and disability (OR = .41, OR = .40, and OR = .23 respectively). White females who were victimized based on gender were .41 times less likely report mid-range feelings of life-satisfaction than those who were not victimized. Also, White females who were victimized based on race, ethnicity, and national origin were .40 times less likely to report mid-range life satisfaction than those who were not bullied. Finally, a White Female was .23 times less likely to report mid-range level of life-satisfaction than other youth. Owing to the lack of frequent or significant association among peer victimization and mid-range life satisfaction, these data are neither tabled nor discussed.

3.5 Life Dissatisfaction and Bullying Behavior Peer Victimization

Black Males

For Black males there was a significant negative relationship between lower levels of life satisfaction and recent truancy from school (OR = 3.18), being victimized because of religion in the past year (OR = 5.59), being victimized because of gender (OR = 3.07), being victimized because of sexual orientation (OR = 4.51), and finally, being victimized because of a mental or physical disability (OR = 4.09).

Black males who were truant from school (past 30 days) because of a fear of victimization were 13.2 times more likely report dissatisfaction with life compared to those who had not been truant. Individuals who had been victimized because of religion were 5.6 times more likely to report lowered levels of life satisfaction than the referent group who had not been victimized. Likewise, adolescents who had been bullied on the basis of gender were 3.07 times more likely to be dissatisfied with life than their counterparts who were not victimized. Those who were bullied because of sexual orientation were 4.5 times more likely to report lower levels of life-satisfaction and those who were victimized because of mental or physical disability were 4.1 times more likely to experience dissatisfaction with life than non-bullied Black male students (Table 3).

White Males

Victimized White males were more likely than other White males to report dissatisfaction with life regarding truancy from school (OR = 3.97), being victimized because of race, ethnicity, or national origin (OR = 2.46), sexual orientation (OR = 3.42), and mental or physical disability (2.92).

White males who were truant from school during the past 30 days because of a fear of being victimized were 4.0 times more likely to report dissatisfaction with life than White males who were not bullied. Also, White males who were victimized because of race, ethnicity, or national origin were 2.5 times more likely to report lower levels of life satisfaction. Being bullied because of sexual orientation increased a White males’ likelihood of reporting lower life satisfaction by 3.4 times. Finally, White males who were victimized based on mental or physical disability were 2.9 times more likely to report dissatisfaction with life than other White males (Table 3).

Black Females

For Black females there were significant relationships detected between the victimization variables and low levels of self-reported life satisfaction. Dissatisfaction with life was significantly and negatively associated with being victimized because of religion (OR = 4.50), race/ethnicity/national origin (OR = 2.53), and physical or mental disability (OR = 2.97).

Black females who were victimized because of religion within the past year were 4.5 times more likely to report dissatisfaction with life. Likewise, Black females who were victimized because of race, ethnicity, or national origin were 2.5 times more likely to report life dissatisfaction than other Black females. Lastly, Black females who were victimized because of physical or mental disability were 3.0 times more likely than Black females who have not been bullied to report dissatisfaction with life (Table 3).

White Females

White females who were dissatisfied with life displayed significant negative associations with various dimensions of victimization. White females who were truant from school because of bullying (OR = 4.84), bullied because of gender (OR = 4.52), race (OR = 3.88), and mental or physical disability (OR = 7.35) were more likely to report be classified as dissatisfied than White females who were not bullied (Table 3).

4 Discussion

Results demonstrated that a number of public high school students in this USA sample reported overall dissatisfaction with their lives. The results of this study also revealed that a substantial number of students from this public high school adolescents were victims of bullying behavior. Furthermore, this study identified significant relationships between self-reported life satisfaction and various forms of peer victimization (e.g., victimization motivated by religion, gender, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, or disability). Most importantly, this study demonstrated that the relationships between life satisfaction and the different forms of peer victimization varied as a function of the students’ race and gender backgrounds, suggesting that the impact of specific forms of victimization may not be universal.

4.1 Victimization Associated with Truancy

A significant relationship was observed between lower levels of life satisfaction and truancy (past 30 days) due to a fear of victimization for Black males, White males, and White females (Table 3). This finding is congruent with previous literature that suggests an association between victimization and truancy (Glew et al. 2005; Siziya et al. 2007). Other studies extend these findings and suggest that students who bully, as well as victims, experience feelings of unhappiness at school (Rigby and Slee 1993; Gladstone et al. 2006).

Black males displayed the greatest levels of life dissatisfaction owing to victimization that promotes truancy. Perhaps gang activity among Black males, which is pervasive nationally and in the southeast USA, may contribute to the fear of being victimized. Therefore, truancy may act as a psychological defense mechanism against being physically or psychologically threatened by gangs (Egley 2002; Small et al. 2000).

Despite the psychological benefits, the effects of truancy can be deleterious to the quality of life for victimized students. Truancy has been associated with impaired academic achievement, fewer financial and educational opportunities, risky sexual behaviors, and substance abuse (Henry and Huizinga 2007; Best et al. 2006; White et al. 2001). Being victimized by peers has previously been associated with a higher likelihood of future unemployment, thus hindering the future earning potential of victimized adolescents (Gladstone et al. 2006).

4.2 Victimization Based on Religion

In this study, there was a significant relationship between being victimized because of religion (past 12 months) and reporting lower levels of life satisfaction for Black males and Black females. Perhaps, African–Americans, in the USA who have been found to display high levels of religiosity are affected by attacks on their faith in different ways than non-Blacks (Taylor et al. 1999).

There has been little research that evaluates relationships between religion and being bullied among adolescents. However, researchers posit that in general, practicing religion is protective against adolescent victimization though this relationship is indirect. (Schreck et al. 2007; Nonnemaker et al. 2003). Of particular interest is the Garrity et al. (1997) argument that people who are perceived to be “different” are at increased likelihood for victimization. Perhaps individuals who are being victimized because of their religion (especially those who may be religious minorities) are targeted by perceptions of being “different” by their peers in this southeastern USA state.

4.3 Victimization Based on Gender

Black males and White females who were victimized because of gender were found to be dissatisfied with life (Table 3) in this study. Females reported a higher prevalence of being victimized than males (Table 1) conflicting with previous research (Haynie et al. 2001; Craig et al. 2009). The school district for this study is relatively close to a major metropolitan area with an increasing gang population. Perhaps the Black males in this study have been victimized via gang recruiting activities or reluctance to join a gang. Violent and aggressive behaviors in females have caught up to male prevalence rates (Steffensmeier et al. 2005) and perhaps for this study White females are being victimized via gender from other aggressive White females and males.

Black females in this sample, reporting victimization because of gender, did not report lower life satisfaction than their White counterparts. Perhaps this finding can be attributed to the same resiliency factors, (religiosity, family support) among Black Women that help to allay other poor psychological outcomes (i.e. poor body image and suicide; Gibbs 1997; Johnson et al. 2004).

Research suggests that adolescent males are more likely to be targeted for physical forms of victimization, whereas females are more often involved in relational forms of victimization (e.g., rumor spreading, social exclusion; Wang et al. 2009). Victimization that adolescents in this study experienced is likely contingent upon the gender of the perpetrator. When adolescents victimize, it is often done in a manner that damages goals valued by their respective gender peer group. For example, males are more likely to use physical forms of victimization because themes of physical dominance are highly valued among males. Females, on the other hand, are more likely to focus on relational issues, social interactions, and forming intimate connections with others. Therefore, aggressive adolescent females will likely victimize a peer by attempting to damage peer relationships (Borg 1999; Wang et al. 2009). It should be noted that victims were not asked in this study to report who was committing the acts of victimization, therefore it is unclear whether students were victimized by individuals of the same or opposite gender. It is possible that males were victimizing females and vice-versa. In addition, it is difficult to determine whether the forms of victimization that the adolescents in this sample experienced were overt or relational.

4.4 Victimization Based on Race, Ethnicity, or National Origin

A significant relationship between dissatisfaction with life and being victimized because of race, ethnicity, or national origin was established for three of the four race/gender groups (White males, White females, and Black females). It should be noted again here, that this sample was approximately 54% Black and 46% White. White males and White females who were dissatisfied with life reported the highest prevalence of victimization owing to race, ethnicity, or national origin (Table 3).

In turn, this study does not support the view that ethnic minorities are at increased likelihood of being victimized by their peers of another race. Blacks are at decreased risk of peer victimization than Whites (Spriggs et al. 2007; Wang et al. 2009). Research also demonstrates that the interaction of race/ethnicity within the social environment (i.e., prevalence of one group greater than another) and ethnicity of the non-dominant group is a useful predictor of victimization risk (Graham and Juvonen 2002; Verkuyten and Thijs 2002). As for school settings, classrooms of homogenous ethnic composition are less prone to incidents of aggression and victimization than classes of heterogeneous makeup (Veervort et al. 2010).

4.5 Victimization Based on Sexual Orientation

Males, both Black and White, displayed a significant association with being victimized because of perceived sexual orientation and dissatisfaction with life. Previous research has determined associations between victimization because of sexual orientation to several negative outcomes (Rivers 2004). Specifically, studies have demonstrated that the effects of victimization on sexual minority youth contribute to alcohol and other substance abuse, running away from home, truancy, and suicide ideation (Friedman et al. 2006; Hershberger and D’Augelli 1995; Huebner et al. 2004a, b; Pilkington and D’Augelli 1995; Rivers 2000, 2004; Valois et al. 2003; Zullig et al. 2001).

Of particular interest is that gay, lesbian, bisexual, and questioning youth are at increased risk of suicide ideation compared to heterosexual youth (Silenzio et al. 2007). Indeed, victimization has been found to mediate the relationship between suicidality and being a sexual minority (Friedman et al. 2006).

It is also interesting to note that, there was no significant association between life satisfaction and being bullied/victimized owing to perceived sexual orientation for females (Black or White) in this study. Perhaps in this sample of high school adolescents in the southeastern USA, male adolescents are less accepting of other males who might be gay, or questioning vis-à-vis their sexual orientation and subsequently victimize those perceived to be gay. In comparison, females who are lesbian, or questioning their sexual orientation do not seem to upset or threaten other (presumed heterosexual) females and in turn, are not bullied or victimized. This finding might also be explained by the negative reaction to the movie “Brokeback Mountain” that contained overt gay male sexual behavior compared to the less negative reaction to the Britney Spears and Madonna kiss that took place at a television awards show. Although highly speculative, it could be fair to state that some cultural groups in the USA might be more comfortable with female same-sex behavior compared to male same-sex behavior.

4.6 Victimization Based on Physical or Mental Disability

Significant associations between lower levels of life satisfaction and peer victimization based on physical or mental disability (past 12 months) were reported for all four race/gender groups, reflecting the particularly serious and pervasive nature of this form of victimization (Table 3). Previous research suggests that adolescents with intellectual disability are at increased risk of being victimized. One study conducted in the UK demonstrated that 59% of disabled high school students were victimized compared to 16% of mainstream children (Sheard et al. 2001). In a 1992 study, Branston et al. found that 37% of students with mental disabilities were victimized compared to 25% of mainstream college students (Branston et al. 1999).

Cleave and Davis suggest that having a developmental disability is linked to being a bully-victim (Cleave and Davis 2006). In addition to the poor mental health aspects associated with being victimized, perhaps the bully-victim status (associated with depression, anxiety etc.) of mentally or physically disabled students indicates further rationale for reduced quality of life/life satisfaction (Kaltiala-Heino et al. 2000).

4.7 Implications

Taken together, these results suggest the importance of different forms of peer victimization to early adolescents’ overall life satisfaction. Furthermore, the strength of the associations between the adolescents’ life satisfaction in relation to peer victimization variables varied for different race and gender groups. Research needs to be conducted to assess the generalizability of these findings to other groups, in particular other minority groups (ethnic, religious, disabled, socio-economic and sexual) and older adolescents. If possible, longitudinal studies should be conducted exploring the directionality of relationships between life satisfaction and peer victimization, beginning in middle school and extending in older adolescence and/or young adulthood. For example, Martin and colleagues (2008) explored longitudinal (1 year) relationships among middle school students’ life satisfaction and peer victimization and prosocial experiences. Results revealed the possibility of bidirectional relationships between early adolescents’ life satisfaction and relational victimization. However, the evidence was stronger for the effect of life satisfaction on relational victimization, that is, lower levels of life satisfaction appeared to be a risk factor for the likelihood of future peer victimization experiences. Additional research needs to explore the possible mediators, especially psychosocial mediators of the associations among life satisfaction and peer victimization (e.g., reduced self-esteem, ability to self defend, reduced self-efficacy for prosocial behaviors, learned helplessness, and social support).

Study limitations should be noted here. These include the use of a cross-sectional study where no temporal sequence of reduced satisfaction as a precursor for non-physical activity behavior can be determined; the use of a geographical sample that may represent youth in this USA southern state, but may not be nationally representative; and the elimination of subjects with missing data on variables of interest as required by the logistic regression analysis program. Such elimination can introduce biases; however, not seriously threatening.

There are several strengths within this study. These include: the large sample size (1,252 subjects for final analysis); the near parity of Black and White students in the sample; and a very high student response rate. Moreover, the dichotomization of victimization and life satisfaction variables allowed detection of conservative relationships and therefore the magnitude of risk may be underestimated (i.e., more toward the null hypothesis of no association among the variables of interest). Also, data were collected from an entire school district for 9th–12th graders representing a universe of high school students.

The findings of this study suggest the need for well-articulated, comprehensive, and possibly race and gender—specific educational interventions to confront and prevent peer victimization. Furthermore, if sound strategies to combat peer victimization are to be formulated, they should be implemented on school-wide levels, not only because many incidents of victimization occur on school grounds, but also because schools function as an important environment for social development (Whitney et al. 1994; MacDonald et al. 2005). “Whole School” approaches that incorporate assessment of victimization and associated academic and mental health variables, school conferences, increased supervision, parent–teacher meetings, communication building with parents, bullies, and victims, and forming bully prevention committees have been found to be effective in reducing incidents of school victimization (Kaltiala-Heino et al. 2000). Furthermore, the use of technology, such as school-sponsored anonymous reporting of victimization via phone and e-mail demonstrated promise for reducing acts of victimization in public high schools in Houston, Texas (Virun 2006). The incidence of victimization indicates a need for proactive efforts by administrators to reduce school victimization. However, an exclusive emphasis on “whole school” approaches might not be equally effective for specific race or gender groups in all situations, as suggested in this study. Comprehensive intervention programs may thus have to include, smaller-scale, contextually-focused intervention components (e.g., group vs. school-wide activities) to be most effective.

References

Andrews, F. M., & Withey, S. B. (1976). Social indicators of well-being: Americans’ perceptions of life quality. New York: Plenum.

Antaramian, S. P., Huebner, E. S., Hills, K. J., & Valois, R. F. (2010). A dual-factor model of mental health: Toward a more comprehensive understanding of youth functioning. Journal of Orthopsychiatry (In review).

Berlan, E. D., Corliss, H. L., Field, A. E., Goodman, E., & Austin, S. B. (2010). Sexual orientation and bullying among adolescents in the growing up today study. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 46(4), 366–371.

Best, D., Manning, V., Gossop, M., Gross, S., & Strang, J. (2006). Excessive drinking and other problem behaviors among 14–16 year old schoolchildren. Addictive Behaviors, 31, 1424–1435.

Borg, M. G. (1999). The extent and nature of bullying among primary and secondary school children. Education Research, 42, 137–153.

Boulton, M. J., Trueman, M., & Murray, L. (2008). Associations between peer victimization, fear of future victimization and disrupted concentration on class work among junior school pupils. The British Journal of Educational Psychology, 67, 473–489.

Branston, P., Fogarty, G., & Cummins, R. A. (1999). The nature of stressors reported by people with an intellectual disability. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 12, 1–10.

Brener, N. D., Collins, J. L., Kann, L., Warren, C. W., & Williams, B. L. (1995). Reliability of the Youth Risk Behavior Survey questionnaire. American Journal of Epidemiology, 141(6), 575–580.

Brener, N. D., Kann, L., McManus, T., Kinchen, S. A., Sundberg, E. C., & Ross, J. G. (2002). Reliability of the 1999 Youth Risk Behavior Survey Questionnaire. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 31, 336–342.

California Healthy Kids Survey. (2006). California Healthy Kids Survey, HSQ 2006–2007, Version H9-Fall 2006. Sacramento: California Department of Education.

Carlyle, K. E., & Steinman, K. J. (2007). Demographic differences in the prevalence, co-occurrence, and correlates of adolescent bullying at school. The Journal of School Health, 77(9), 623–629.

Cleave, J. V., & Davis, M. M. (2006). Bullying and peer victimization among children with special health care needs. Pediatrics, 118, 1212–1219.

Craig, W., Harel-Fisch, Y., Fogel-Grinvald, H., Dostaler, S., Hetland, J., Simons-Morton, B., et al. (2009). A cross-national profile of bullying and victimization among adolescents in 40 countries. International Journal of Public Health, 54(2), 216–224.

Diener, E., Suh, E., Oishi, S., Lucas, R. E., & Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective well-being: three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125, 276–302.

Due, P., Holstein, B. E., Lynch, J., Diderichsen, F., Gabhain, S. N., Scheidt, P., et al. (2005). Bullying and symptoms among school-aged children: international comparative cross sectional study in 28 countries. European Journal of Public Health, 15(2), 128–32.

Egley, A. J. (2002). OJJDP Fact Sheet; National Youth Gang Survey Trends from 1996 to 2000. US Department of Justice.

Eisenberg, M. E., & Aalsma, M. C. (2005). Bully and peer victimization: Position paper by the Society for Adolescent Medicine. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 36, 88–91.

Eisenberg, M. E., Neumark-Sztainer, D., & Story, M. (2003). Associations of weight-based teasing and emotional well-being among adolescents. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 157(8), 733–738.

Epp, J. (1986). Achieving health for all: A framework for health promotion. Ottawa: Health and Welfare Canada.

Fekkes, M., Pijpers, F. I., Fredriks, A. M., Vogels, T., & Verloove-Vanhorick, S. P. (2006). Do bullied children get ill, or do ill children get bullied? A prospective cohort study on the relationship between bullying and health-related symptoms. Pediatrics, 117, 1568–1574.

Friedman, M. S., Koeske, G. F., Silvestre, A. J., Korr, W. S., & Sites, E. W. (2006). The impact of gender role nonconforming behavior, bullying, and social support on suicidality among gay male youth. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 38, 621–623.

Garrity, C., Jens, K., Porter, W., Sager, N., & Short-Camilli, C. (1997). Bully proofing your school: creating a positive environment. Intervention in School Clinic, 32, 235–243.

Gibbs, J. T. (1997). African–American suicide: a cultural paradox. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 27(1), 68–79.

Gladstone, G. L., Parker, G. B., & Malhi, G. S. (2006). Do bullied children become anxious and depressed adults?: A cross-sectional investigation of the correlates of bullying and anxious depression. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 194(3), 201–208.

Glew, G. W., Ming-Yu, F., Katon, W., Rivara, F. P., & Kernic, M. A. (2005). Bullying, psychosocial adjustment and academic performance in elementary school. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 159, 1026–1031.

Graham, S., & Juvonen, J. (2002). Ethnicity, peer harassment and adjustment in middle school: an exploratory study. Journal of Early Adolescence, 22, 173–99.

Greenspoon, P. J., & Saklofske, D. H. (1997). Validity and reliability of the multidimensional students’ life satisfaction scale. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 15, 138–155.

Hawker, D. S., & Boulton, M. J. (2000). Twenty years’ research on peer victimization and psychosocial maladjustment: A meta-analytic review of cross-sectional studies. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 41, 441–455.

Haynie, D. L., Nansel, T. R., & Eitel, P. (2001). Bullies, victims and bully/victims: Distinct groups of youth at-risk. Journal of Early Adolescence, 21, 29–50.

Henry, K. L., & Huizinga, K. L. (2007). Truancy’s effect on the onset of drug use among urban adolescents placed at–risk. Journal of Adolescent Health, 40(4), e9–e17.

Hershberger, S. L., & D’Augelli, A. R. (1995). The Impact of victimization on the mental health and suicidality of lesbian, gay, and bisexuality youths. Developmental Psychology, 31, 65–74.

Huebner, E. S. (1994). Preliminary development and validation of a multidimensional life satisfaction scale for children. Psychological Assessment, 6, 149–158.

Huebner, E. S. (2004). Research on assessment of life satisfaction of children and adolescents. Social Indicators Research, 66, 3–33.

Huebner, E. S., Gilman, R., & Laughlin, J. E. (1999). A multi-method investigation of the multidimensionality of children’s well-being reports: Discriminant validity of life satisfaction and self-esteem. Social Indicators Research, 46, 1–22.

Huebner, E. S., Drane, J. W., & Valois, R. F. (2000). Adolescents’ perceptions of their quality of life. School Psychology International, 21(3), 281–292.

Huebner, D. M., Rebchook, G. M., & Kegeles, S. M. (2004a). Experiences of harassment, discrimination, and physical violence among young gay and bisexual men. American Journal of Public Health, 94, 1200–1203.

Huebner, E. S., Valois, R. F., Suldo, S. M., Smith, L. C., McKnight, C. G., Seligson, J. J., et al. (2004b). Perceived quality of life: a neglected component of adolescent health assessment and intervention. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 34(4), 270–278.

Huebner, E. S., Seligson, J. L., Valois, R. F., & Suldo, S. M. (2006). A review of the brief multidimensional students’ life satisfaction scale. Social Indicators Research, 79, 477–484.

Jessor, R. (1993). Successful adolescent development among youth in high risk settings. The American Psychologist, 48(2), 117–126.

Johnson, C., Crosby, R., Engel, S., Mitchell, J., Powers, P., Wittrock, D., et al. (2004). Gender, ethnicity, self-esteem and disordered eating among college athletes. Eating Behaviors, 5(2), 147–156.

Kaltiala-Heino, R., Rimpela, M., Rantanen, P., & Rimpela, A. (2000). Bullying at school: an indicator of adolescents at risk for mental disorders. Journal of Adolescence, 23, 661–674.

Kolbe, L. J. (1990). An epidemiological surveillance system to monitor the prevalence of youth behaviors that most affect health. American Journal of Health Education, 21(6), 44–48.

Lewinsohn, P. M., Redner, J., & Seeley, J. R. (1991). The relationship between life satisfaction and psychosocial variables: New perspectives. In F. Strack, M. Argyle, & N. Schwartz (Eds.), Subjective well being (pp. 141–169). Oxford: Pergamon.

MacDonald, J. M., Piquero, A. R., Valois, R. F., & Zullig, K. J. (2005). The relationship between life satisfaction, risk-taking behaviors and youth violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 20(11), 1495–1518.

Martin, K., Huebner, E. S., & Valois, R. F. (2008). Does life satisfaction predict victimization experiences in adolescence? Psychology in the Schools, 45(8), 1–9.

Menesini, E., Modena, M., & Tani, F. (2009). Bullying and victimization in adolescence: concurrent and stable roles and psychological health symptoms. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 170(2), 115–133.

Nonnemaker, J. M., McNeely, C. A., & Blum, R. W. (2003). Public and private domains of religiosity and adolescent health risk behaviors: evidence from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Social Science & Medicine, 57(11), 2049–2054.

Olweus, D. (1993). Bullying at school: what we know and what we can do. Cambridge: Blackwell.

Park, H. S., Schepp, K. G., Jang, E. H., & Koo, H. Y. (2006). Predictors of suicidal ideation among high school students by gender in South Korea. The Journal of School Health, 76(5), 181–188.

Pilkington, N. W., & D’Augelli, A. R. (1995). Victimization of lesbian gay and bisexual youth in community settings. Journal of Community Psychology, 23, 33–56.

Proctor, C. L., Linley, P. A., & Maltby, J. (2008). Youth life satisfaction: a review of the literature. Journal of Happiness Studies, 10, 583–630.

Raphael, D. (1996). The determinants of adolescent health: Evolving definitions, recent findings, and proposed research agenda. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 19, 6–16.

Renwick, R., Brown, I., & Nagler, N. (Eds.). (1996). Quality of life in health promotion and rehabilitation: conceptual approaches, Issues and applications. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Rigby, K., & Slee, P. T. (1993). Dimensions of interpersonal relation among Australian children and implications for psychological well-being. The Journal of Social Psychology, 133, 33–42.

Rivers, I. (2000). Social exclusion, absenteeism, and sexual minority youth: Support for learning. British Journal of Learning Support, 5, 13–18.

Rivers, I. (2004). Recollections of bullying at school and their long-term implications for lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals. Crisis, 25(4), 169–175.

Roland, E. (2002). Aggression, depression, and bullying others. Aggressive Behavior, 28, 198–206.

Saluja, G., Iachan, R., Scheidt, P. C., Overpeck, M. D., Sun, W., & Giedd, J. N. (2007). Prevalence and risk factors of depressive symptoms among young adolescents. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 158(8), 760–765.

Schreck, C. J., Burek, M. W., & Clark-Miller, J. (2007). He sends rain upon the wicked: a panel study of the influence of religiosity on violent victimization. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 22(7), 872–893.

Seligman, M., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology: an introduction. The American Psychologist, 55, 5–14.

Seligson, J. L., Huebner, E. S., & Valois, R. F. (2003). Preliminary validation of the Brief Multidimensional Student’s Life Satisfaction Scale (BMSLSS). Social Indicators Research, 61, 121–145.

Sheard, C., Clegg, J., Standen, P., & Cromby, J. (2001). Bullying and people with severe intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 45(5), 407–415.

Silenzio, V. M., Pena, J. B., Duberstein, P. R., Cerel, J., & Knox, K. L. (2007). Sexual orientation and risk factors for suicidal ideation and suicide attempts among adolescents and young adults. American Journal of Public Health, 97, 2017–2019.

Siziya, S., Muula, A. S., & Rudatsikira, E. (2007). Prevalence and correlates of truancy among adolescents in Swaziland: findings from the Global School-Based Health Survey. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 1(1), 15–23.

Small, M. A., Limber, S. P., & Kimbrough-Melton, R. L. (2000). Gangs in South Carolina: An exploratory study. Executive Summary, Clemson University, January 2000.

Spriggs, A. L., Iannotti, R. J., Nansel, T. R., & Haynie, D. L. (2007). Adolescent bullying involvement and perceived family, peer and school relations: commonalities and differences across race/ethnicity. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 41, 283–293.

Statistical Analysis System (SAS), PC SAS 9.1.3. (2006). SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina.

Steffensmeier, D., Schwartz, J., Zhong, H., & Ackerman, J. (2005). An assessment of recent trends in girls’ violence using diverse longitudinal sources: is the gender gap closing. Criminology, 43(2), 335–342.

Suldo, S. M., & Shaffer, E. J. (2008). Looking beyond psychopathology: the dual-factor model of mental health in youth. School Psychology Review, 37(1), 52–68.

Taylor, R. J., Mathis, J., & Chatters, L. M. (1999). Subjective religiosity among African Americans: a synthesis of findings from five national samples. Journal of Black Psychology, 25(4), 524–543.

Thompson, D., Whitney, I., & Smith, P. (2007). Bullying of children with special needs in mainstream schools. Support for Learning, 9(3), 103–106.

Van der Wall, M. F., De Wit, C. M., & Hirasing, R. A. (2003). Psychological health among young victims and offenders of direct and indirect bullying. Pediatrics, 111, 1312–1317.

Valois, R. F., Zullig, K. J., Huebner, E. S., & Drane, J. W. (2001). Relationship between life satisfaction and violent behaviors among adolescents. American Journal of Health Behavior, 25(4), 353–366.

Valois, R. F., Zullig, K. J., Huebner, E. S., & Drane, J. W. (2003). Life satisfaction and suicide among high school adolescents. Social Indicators Research, 66(1), 81–105.

Veervort, M., Scholte, R., & Overbeek, G. (2010). Bullying and victimization among adolescents: The role of ethnicity and ethnic composition of school class. Journal of Youth Adolescence, 39, 1–11.

Verkuyten, M., & Thijs, J. (2002). Racist victimization among children in the Netherlands: a short survey for assessing health and social problems of adolescents. The Journal of Family Practice, 38, 489–494.

Virun, S. (2006). School Promotes High Tech Tip Line. Houston Chronicle. HoustonChronicle.com/disp/story.mpl/metropolitan/4329783.html. Accessed 15 Nov 2006.

Wang, J., Iannotti, R. J., & Nansel, T. R. (2009). School bullying among adolescents in the United States: physical, verbal, relational and cyber. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 45, 368–375.

White, M. D., Fyfe, J. J., Campbell, S. P., & Goldkamp, J. S. (2001). The school–police partnership: Identifying at-risk youth through a truant recovery program. Evaluation Review, 25(5), 507–532.

Whitney, I., Rivers, I., Smith, P. K., & Sharp, S. (1994). The Sheffield project: Methodology and findings. In P. K. Smith & S. Sharp (Eds.), School bullying: Insights and perspectives (pp. 20–56). London: Routledge.

Wilkins-Shurmer, A., O’Callaghan, M. J., Najman, J. M., Bor, W., Williams, G. M., & Anderson, M. J. (2003). Association of bullying with adolescent health-related quality of life. Journal of Pediatric Child Health, 39, 436–441.

Zullig, K. J., Valois, R. F., Huebner, E. S., Oeltmann, J. E., & Drane, J. W. (2001). Relationship between perceived life satisfaction and adolescents’ substance abuse. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 29, 279–288.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kerr, J.C., Valois, R.F., Huebner, E.S. et al. Life Satisfaction and Peer Victimization Among USA Public High School Adolescents. Child Ind Res 4, 127–144 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-010-9078-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-010-9078-y