Abstract

Problematic social media use consists of use that interferes with individuals’ functioning, such as for example in failing to complete important tasks. A number of studies have investigated the association of trait mindfulness with problematic social media use. This meta-analysis synthesised research from 14 studies and a total of 5355 participants to examine the association between mindfulness and problematic social media use across studies. A lower level of mindfulness was associated with more problematic social media use, with a weighted effect size of r = -.37, 95% CI [-.42, -.33], k = 14, p < .001.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The use of social media, which allows for the exchange of information and ideas through online platforms, has increased rapidly worldwide. Accumulated research evidence indicates that social media use can lead to problematic symptoms in some individuals (Kuss & Griffiths, 2017). Such problematic use involves devoting a great amount of time and energy using social media, to the degree that an individual’s social activities, interpersonal relationships, studies, job, or health and wellbeing are impaired (Sun & Zhang, 2021).

In a comprehensive review of conceptualisations of problematic social media use, Sun and Zhang (2021) summarised problematic social media use as involving maladaptive use of social media that interferes with individuals’ functioning, for example in failing to complete important tasks or failing to regulate the amount of time spent engaging in social media use. Harm associated with problematic social media use can include poor sleep, depression, anxiety, and psychological distress (Keles et al., 2020; Marino et al., 2018). Adolescents are potentially at a greater risk of developing problematic social media use due to their limited capacity for self-regulation and vulnerability to peer pressure (Keles et al., 2020).

Some controversy surrounds how this problematic use should be classified (Kardefelt-Winther et al., 2017). For example, Sun and Zhang (2021) argued that it is premature to pathologise excessive social media use, and there is currently no official diagnosis for any disorder involving the use of modern technology (Aarseth et al., 2017). Framing of social media use by the media in some countries has caused concerns about the technology (Lundahl, 2021), and in response some researchers have suggested suggest that the broad opportunities and unknown consequences provided by social media platforms may accentuate the proclivity to panic about the harms of the new technology (Walsh, 2020).

Theories of mindfulness

Mindfulness involves awareness of the present moment in an open and non-judgmental manner (Brown & Ryan, 2003). Mindfulness differs from other kinds of self-awareness traditionally studied because it does not have a cognitive or intellectual foundation and is, instead, viewed as having a foundation in nonevaluative perception (Brown & Ryan, 2003). As Li (2021) pointed out, important aspects of mindfulness are attention and awareness. Trait or dispositional mindfulness is characterised by a general tendency for non-critical attentional focus on present experiences, cognitions, perceptions, and emotions (Rosenthal et al., 2021). Studies have shown that trait mindfulness is associated with lower neuroticism and negative affect (Giluk, 2009), better mental health, more adaptive cognitive processes, more effective processing and regulation of emotion, and fewer symptoms of depression and anxiety (Tomlinson et al., 2018).

Research findings also indicate that interventions that increase trait mindfulness can reduce symptoms of various mental disorders and improve health. Meta-analyses have found that mindfulness-based interventions can reduce symptoms of depression and anxiety (Hofmann et al., 2010), post-traumatic stress (Hopwood & Schutte, 2017), and other disorders (Cavicchioli et al., 2018). Further, meta-analyses have found that mindfulness training impacts telomerase and telomere length, which are biomarkers connected to physical health (Schutte & Malouff, 2014; Schutte et al., 2020).

Mindfulness and problematic social media use

Researchers have begun identifying various individual differences associated with problematic social media use, such as the Big Five characteristics and mindfulness (Kircaburun et al., 2019). Studies investigating these individual differences suggest that greater levels of trait mindfulness may be associated with lower problematic use (e.g., Kircaburun et al., 2019; Weaver & Swank, 2021). Mindfulness can be improved through mindfulness-based interventions (Sommers-Spijkerman et al., 2021). Thus, the connection between mindfulness and problematic social media use may be of special interest to those working on preventing or treating problematic use.

Attention and awareness are central in the relationship between mindfulness and problematic social media use. Dispositional mindfulness involves greater capacity for attentional focus, which predicts fewer symptoms of problematic use (Throuvala et al., 2020). A low level of trait mindfulness limits one’s ability to direct attention and awareness to tasks and goals instead of being distracted by notifications and habitual social media checking behaviour, and may be related to problematic use (Du et al., 2021). Similarly, the improved attentional focus in individuals with greater trait mindfulness may reduce the likelihood of developing problematic social media use as mindfulness may reduce the frequency of distraction through a greater awareness of current thoughts and emotions (Throuvala et al., 2020). Problematic social media use may involve difficulties regulating negative emotions (Brand et al., 2019), which is a characteristic of individuals with low dispositional mindfulness (Giluk, 2009).

Research studies have started to investigate whether improvements to trait mindfulness can reduce symptoms of problematic social media use (Throuvala et al., 2020; Weaver, 2021). In a study examining the effect of mindfulness training on smart phone use, Throuvala et al., (2020) found that this training reduced some aspects of problematic use. A possible path between increased mindfulness and less problematic use may by that improving mindfulness increases top-down cognitive control and emotional regulation, which both predict fewer symptoms of problematic use (Weaver & Swank, 2019).

Rationale and objectives

A theoretical rationale for predicting that higher mindfulness is associated with less problematic social media use is that the attentional focus involved in mindfulness allows individuals to focus on goal-relevant thoughts and behaviours (Du et al., 2021; Li, 2021; Throuvala et al., 2020), with less likelihood of being distracted by social media notifications or habitual checking of social media platforms. A number of studies have investigated the relationship between mindfulness and problematic social media use. The association of mindfulness with problematic social media use across studies is not known and a meta-analysis can fill this gap in the literature. The present meta-analysis synthesised research on the association between trait mindfulness and problematic social media use. It was hypothesised that across studies greater mindfulness would be associated with lower problematic use.

Method

Search strategy

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses statement (Page et al., 2021) guided the search strategy and reporting of the meta-analysis. The protocol for this meta-analysis was published in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews, registration number [removed to preserve anonymity of the authors]. We systematically searched the following databases: EBSCO, EBSCO Open Dissertations, ProQuest, and PubMed. No restrictions were placed on publication date, language, or peer review status. The search terms were Mindful* AND ("social media addiction" OR “social networking addiction” OR "Facebook addiction" OR "problematic social media use" OR “problematic social networking” OR “problematic social network” OR “problematic Facebook use" OR “compulsive social media use” OR “compulsive social networking” OR “compulsive social network” OR “compulsive Facebook use” OR "social media dependence" OR “social networking dependence” OR “social network dependence” OR "Facebook dependence"). Reference lists of included articles were searched to identify additional relevant research, then forward citation searches with Google Scholar were used to identify further relevant research. Studies were screened by title and abstract, and then full text. We emailed the authors of included articles to request any unpublished data that met the criteria for inclusion in the meta-analysis.

Eligibility criteria

To be included in this meta-analysis, studies had to measure problematic social media use (not simply use or frequent use) and trait mindfulness (not state mindfulness), and report the Pearson r correlation for the association of these variables or provide statistical information that could be converted to r.

Data extraction and coding

Data extracted from each study to calculate weighted effect sizes were the Pearson r correlation coefficient and sample size. We also extracted the mean age of the sample, the percentage of female participants, the scales used to measure mindfulness and problematic social media use and their reliability, and whether there was apparent evidence of validity for these scales. When studies did not report needed information, we contacted the author of the study to obtain the missing information. A missing association was obtained through this approach for one study (Turel & Osatuyi, 2017). Two authors independently coded the data required for the effect-size and moderator analyses. The agreement between the two coders was 96%. Disagreements were resolved by consensus among the researchers.

Data analysis

Analyses were performed using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Software (version 3.3.070). The meta-analysis used a random-effects model, as the true effect size likely varies across studies due to significant heterogeneity in sample characteristics and the questionnaires used to assess mindfulness and problematic social media use. Heterogeneity of effect sizes was evaluated using (i) Cochran’s Q test of variance of effect sizes across studies, (ii) the I2 statistic of proportion of true variation in observed effects, and (iii) tau2 estimate of variance of true effects among studies (Higgins, 2008).

We evaluated the impact of publication bias with Egger’s test for funnel plot asymmetry (Egger et al., 1997), Begg’s rank correlation test (Begg & Mazumdar, 1994), and Duval and Tweedie’s trim-and-fill method (Duval & Tweedie, 2000). We used multivariate meta-regression to test for significant study quality, sex- and age-related moderator effects.

A supplementary analysis examined effect sizes for the subset of studies that also reported a standardised beta the effect size when control variables, such as time 2 scores when time 1 scores were assessed at time 1, or factors such as fear of missing out were controlled, in a multivariate analysis. Ferguson (2015) pointed out that bivariate associations tend to overestimate the true relationship between variables when control variables are not included.

Results

Results of literature search

The study selection process is shown in the PRISMA chart in Fig. 1. Twelve of the included studies were identified through keyword searches and two were identified using the forward citation searches with Google Scholar. Key characteristics of the 14 included studies are displayed in Table 1. Twelve of the studies were cross-sectional. One of the included studies was experimental and tested a 10-day intervention in a pre-post design (Throuvala et al., 2020); we used the correlation between mindfulness and problematic social media use at baseline as the effect size. One of the included studies was longitudinal (Du et al., 2021); we used the correlation between mindfulness and problematic social media use at T1 as the effect size for the main analysis and the effect size at T2 with the effect size at T1 as a covariate for the supplemental analysis. Two studies measured problematic Facebook use (Eşkisu et al., 2020; Turel & Osatuyi, 2017), one study measured WhatsApp use (Apaolaza et al., 2019), and the remaining studies measured problematic social media use in general. We were unable to investigate the type of social media was a potential moderator because not enough studies measured problematic use of social media platforms other than Facebook. The final sample included 5355 participants (61% females, mean age = 22 years). The data file used to run the analyses is at [https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/FPG7U].

Quality assessment

To assess the quality of research included in the present meta-analysis, the determining study characteristic was whether valid and reliable scales were used to measure mindfulness and problematic social media use. All the studies included in the meta-analysis measured mindfulness using scales with evidence of reliability and validity. All but one study (Liu et al., 2022) measured problematic social media use with scales having apparent evidence of reliability and validity as described below. We used reliability and validity of scales to create a four-point quality measure, with one point given for acceptable reliability and evidence of validity for each of the two measures used in the bivariate association measurement in each study. A consideration regarding quality comes from, Almourad et al. (2020), who pointed out that measurement of problematic use of digital technology, such as social media use, can be difficult. This difficulty stems in part from divergent conceptualisations, as well as possible overlap between the functionality of devices. Thus, measures of problematic social media use may capture somewhat different aspects of this problematic use.

Scales measuring mindfulness

Seven studies measured mindfulness with the Mindful Attention and Awareness Scale (MAAS; Brown & Ryan, 2003), for which evidence of validity and reliability has been reported in several languages (Deng et al., 2012; Jermann et al., 2009). Two studies used the Child and Adolescent Mindfulness Measure (CAMM; Greco et al., 2011); evidence of reliability and validity has been reported for the CAMM in several languages (Chen et al., 2022; Chiesi et al., 2017). One study measured mindfulness with the Five-Factor Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ; Baer et al., 2006), and two studies used the Acting with Awareness subscale of the FFMQ; evidence suggests that both the FFMQ and the Acting with Awareness subscale are valid and reliable measures of mindfulness (Christopher et al., 2012). Gainza Perez (2022) reported a separate correlation for problematic social media use for each facet of mindfulness measured by the FFMQ instead of a correlation for overall mindfulness, so we chose the correlation reported for the Acting with Awareness subscale as the effect size for the study, since this subscale has the strongest association with overall mindfulness measured by the FFMQ (Christopher et al., 2012). Correia (2019) adapted the MAAS to measure mindful attention and awareness while using social media and provided evidence of validity and reliability for this newly created scale.

Scales measuring problematic social media use

Five studies measured social media use with the Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale (BSMAS; Andreassen et al., 2016), which was adapted from the Bergen Facebook Addiction Scale (BFAS; Andreassen et al., 2012. Four studies measured social media use with the Compulsive Social Networking Scale (Serenko & Turel, 2015), which was adapted from the Compulsive Buying Scale (Faber & O'Guinn, 1992). One study measured problematic use with the Social Media Use Questionnaire (Xanidis & Brignell, 2016). One study used the Social Media Self-Control Failure Scale (Du et al., 2018). One study used the Social Media Disorder Scale (van den Eijnden et al., 2016). One study adapted the Chen Internet Addiction Scale (Ceyhan et al., 2019; Chen et al., 2003) to specifically measure problematic Facebook use by replacing “Internet” with “Facebook” in every item. Evidence of validity and reliability was provided for each of the above scales in the study which developed the scale.

Only one study measured problematic social media use with a scale without apparent evidence of validity (Liu et al., 2022). This study measured problematic social media use with the Mobile Phone Addiction Type Scale (Liu, 2019) which was developed in an unpublished doctoral dissertation. While Liu et al. (2022) reported evidence of reliability for this scale, they did not report information indicating that the scale has evidence of validity.

Meta-analytic effect size

The random-effects model showed a significant association between lower mindfulness and greater problematic social media use (r = -0.37, 95% CI [-0.42, -0.33], k = 14, p < 0.001). Figure 2 shows the forest plot of correlations between mindfulness and problematic social media use for each study. There was significant heterogeneity in effect sizes across the included studies (Q(13) = 44.53, p < 0.001, I2 = 70.81, tau2 = 0.007). Half of the included studies also reported a standardised beta after controlling for other variables. The effect size for studies controlling for other variable, with beta converted to r for comparison with the results of the main analysis, was somewhat lower ((r = -0.30, 95% CI [-0.38, -0.22], k = 7, p < 0.001) than the effect size for the main analysis.

Moderator analyses

Study quality was not a significant moderator of the main effect size (coefficient = -0.07, p = 0.23). Two studies were excluded from the multivariate meta-regression examining the moderating effect of sex of participants because these studies did not report the proportion of female participants (Hassan & Pandey, 2021; Liu et al., 2022). No significant association was found between effect size and proportion of females in the sample (coefficient = 0.000, p = 1.00). Sample age also was not significant as a moderator (coefficient = 0.006, p = 0.29).

Sensitivity analyses and publication bias

Sensitivity analyses using the one-study removed method showed that the findings of the meta-analysis were robust to the removal of any of the included studies. Removing any one study from the analysis resulted in a pooled effect size between r = -0.36 and r = -0.39, significant at p < 0.001.

Figure 3 shows the funnel plot of effect sizes for the 14 included studies. Egger’s test for asymmetry of the funnel plot was not significant (p = 0.72) and Begg’s rank test was not significant (p = 0.91); both tests suggested that the results were not affected by publication bias. The trim-and-fill analysis indicated that it was not necessary to adjust the estimated effect size by imputing missing studies. The results of these analyses indicate that it is unlikely the results of the meta-analysis were impacted by publication bias.

Discussion

The present meta-analysis synthesised research investigating the association between trait mindfulness and problematic social media use. The meta-analysis found a significant association of r = -0.37 between lower trait mindfulness and greater problematic use across studies. This is a medium effect size according to Cohen’s (1992) criteria. This significant relationship across studies between mindfulness and problematic social media use expands the realms in which mindfulness may play an important role. Previous research indicates that mindfulness is important in settings ranging from the therapeutic (Khoury et al., 2013), to organisations (Reb, et al., 2020) to classrooms (Wang et al., 2021).

The association found in the present meta-analysis does not indicate the nature of the causal relationship between these variables. It is possible that a low level of trait mindfulness causes problematic social media use and/or vice-versa. Additionally, other factors, such as poor mental health or difficult life circumstances might lead to both less mindfulness and greater tendency towards problematic use. The supplementary analysis examining the effect size of standardised betas for studies that included control variables, which found a lower effect size than the analysis of bi-variate association, provides some support for this proposition.

Two studies have provided evidence that improving mindfulness reduces problematic social media use (Throuvala et al., 2020; Weaver, 2021), and one study has found that problematic social media use reduces mindfulness, which consequently causes further future problematic use (Du et al., 2021). Experimental evidence suggests that mindfulness-based interventions that improve mindfulness also reduce symptoms of problematic use (Throuvala et al., 2020; Weaver, 2021).

Throuvala et al. (2020) provided experimental evidence that mindfulness-based interventions can reduce symptoms of problematic social media use. The researchers tested the effectiveness of a 10-day online mindfulness-based intervention, which resulted in significant increases in mindfulness and reductions in problematic use for the 72 participants who received the intervention. A similar result was found by Weaver (2021) in a 5-week mindfulness-based intervention. It is also possible that problematic social media use reduces a person’s trait mindfulness, since social media use can lead to a diminished capacity to be attentive and aware of current tasks and goals (Du et al., 2021). Du et al. (2021) provided evidence suggesting that the relationship between mindfulness and problematic social media use is bi-directional, using a 3-wave longitudinal study design. Their study found partial support for the hypothesis that greater problematic social media use at Time 1 predicted lower mindfulness at Time 2, which in turn predicted greater problematic social media use at Time 3 (Du et al., 2021).

These results suggest that the relationship between mindfulness and problematic social media use may be intertwined, in that they may be bi-directional and that other factors may influence both mindfulness and problematic social media use. Higher trait mindfulness may be a protective factor that prevents the development of problematic use, and similarly, low trait mindfulness may be a risk factor for the development of problematic use as diminished attention and awareness increases the likelihood of being distracted by notifications and automatic social media checking behaviour (Du et al., 2021). Mindfulness-based interventions may be effective for treating problematic social media use due to the improvements in top-down cognitive control resulting from these interventions (Rosenthal et al., 2021). These improvements in cognition can aid in changing the automatic and habitual responses to cravings and external stimuli that lead an individual to engage in problematic behaviour (Brand et al., 2019; Rosenthal et al., 2021).

A reciprocal relationship would mean that the effects of low mindfulness on problematic social media use are compounded or amplified, since low trait mindfulness can result in greater problematic use, which leads to further reductions in mindfulness, creating a harmful spiral. A reciprocal relationship also suggests that the effects of mindfulness interventions on problematic social media use could lead to a beneficial upward spiral, with greater mindfulness leading to lower problematic use, which may lead to further improvement in trait mindfulness.

Limitations

All the included studies used self-report measures of mindfulness and problematic social use and therefore relied on participants’ awareness of their own behaviour. That awareness could be low in some individuals. Further, few studies measuring problematic use on a social media platform other than Facebook met the inclusion criteria, so we were unable to conduct a moderator analysis examining whether the relationship between mindfulness and problematic use varies between different social media platforms. Finally, it is unclear to what extent demand characteristics may have influenced participant responses across studies.

Directions for future research

There is currently limited experimental evidence indicating whether mindfulness training is effective for reducing symptoms of problematic social media use. Further research is needed to investigate the duration of mindfulness training that is required to cause a significant and lasting improvement in trait mindfulness and problematic use. Studies are also needed to investigate whether the benefits of these interventions last over time and whether mindfulness-based interventions that are conducted over a longer period of time result in greater or longer-lasting reductions in problematic use, as was found, for example, for effects of mindfulness training on post-traumatic stress (Hopwood & Schutte, 2017). More experimental and longitudinal studies are needed to evaluate whether problematic social media use reduces mindfulness and to investigate a potential reciprocal relationship between low mindfulness and symptoms of problematic use.

Data availability

The data used in the analyses is available at [https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/FPG7U].

References

* Indicates studies included in the meta-analysis

Aarseth, E., Bean, A. M., Boonen, H., Colder Carras, M., Coulson, M., Das, D., Deleuze, J., Dunkels, E., Edman, J., Ferguson, C. J., Haagsma, M. C., Helmersson Bergmark, K., Hussain, Z., Jansz, J., Kardefelt-Winther, D., Kutner, L., Markey, P., Nielsen, R. K. L., Prause, N., . . . Van Rooij, A. J. (2017). Scholars’ open debate paper on the World Health Organization ICD-11 Gaming Disorder proposal. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 6(3), 267–270. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.5.2016.088

Almourad, M. B., McAlaney, J., Skinner, T., Pleya, M., & Ali, R. (2020). Defining digital addiction: Key features from the literature. Psihologija, 53(3), 237–253. https://doi.org/10.2298/PSI191029017A

Andreassen, C. S., Torsheim, T., Brunborg, G. S., & Pallesen, S. (2012). Development of a Facebook Addiction Scale. Psychological Reports, 110(2), 501–517. https://doi.org/10.2466/02.09.18.PR0.110.2.501-517

Andreassen, C. S., Billieux, J., Griffiths, M. D., Kuss, D. J., Demetrovics, Z., Mazzoni, E., & Pallesen, S. (2016). The relationship between addictive use of social media and video games and symptoms of psychiatric disorders: A large-scale cross-sectional study. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 30(2), 252–262. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000160

Apaolaza, V., Hartmann, P., D’Souza, C., & Gilsanz, A. (2019). Mindfulness, compulsive mobile social media use, and derived stress: The mediating roles of self-esteem and social anxiety. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 22(6), 388–396. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2018.0681

Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., Hopkins, J., Krietemeyer, J., & Toney, L. (2006). Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment, 13(1), 27–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191105283504

Begg, C. B., & Mazumdar, M. (1994). Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics, 50(4), 1088–1101. https://doi.org/10.2307/2533446

*Bilgiz, S., & Peker, A. (2021). The mediating role of mindfullnes in the relationship between school burnout and problematic smartphone and social media use. International Journal of Progressive Education, 17(1), 68-85.

Brand, M., Wegmann, E., Stark, R., Müller, A., Wölfling, K., Robbins, T. W., & Potenza, M. N. (2019). The interaction of person-affect-cognition-execution (I-PACE) model for addictive behaviors: Update, generalization to addictive behaviors beyond internet-use disorders, and specification of the process character of addictive behaviors. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 104, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.06.032

Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 822–848. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822

Cavicchioli, M., Movalli, M., & Maffei, C. (2018). The clinical efficacy of mindfulness-based treatments for alcohol and drugs use disorders: A meta-analytic review of randomized and nonrandomized controlled trials. European Addiction Research, 137–162. https://doi.org/10.1159/000490762

Ceyhan, E., Boysan, M., & Kadak, M. T. (2019). Associations between online addiction attachment style, emotion regulation depression and anxiety in general population testing the proposed diagnostic criteria for internet addiction. Sleep and Hypnosis, 21(2), 123–139. https://doi.org/10.5350/Sleep.Hypn.2019.21.0181

Chen, S.-H., Weng, L.-J., Su, Y.-J., Wu, H.-M., & Yang, P.-F. (2003). Development of a Chinese Internet Addiction Scale and its psychometric study. Chinese Journal of Psychology, 45, 279–294.

Chen, X., Liang, K., Huang, L., Mu, W., Dong, W., Chen, S., Chen, S., & Chi, X. (2022). The psychometric properties and cutoff score of the Child and Adolescent Mindfulness Measure (CAMM) in Chinese primary school students. Children, 9(4), 499. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9040499

Chiesi, F., Dellagiulia, A., Lionetti, F., Bianchi, G., & Primi, C. (2017). Using item response theory to explore the psychometric properties of the Italian version of the Child and Adolescent Mindfulness Measure (CAMM). Mindfulness, 8(2), 351–360. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-016-0604-y

Christopher, M. S., Neuser, N. J., Michael, P. G., & Baitmangalkar, A. (2012). Exploring the psychometric properties of the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire. Mindfulness, 3(2), 124–131. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-011-0086-x

*Correia, J. (2019). Mindfulness: A potential mitigating mechanism for conditioned problematic social media use (Publication No. 13883036) [Doctoral dissertation, Washington State University]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.

Deng, Y.-Q., Li, S., Tang, Y.-Y., Zhu, L.-H., Ryan, R., & Brown, K. (2012). Psychometric properties of the Chinese translation of the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS). Mindfulness, 3(1), 10–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-011-0074-1

Du, J., van Koningsbruggen, G. M., & Kerkhof, P. (2018). A brief measure of social media self-control failure. Computers in Human Behavior, 84, 68–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.02.002

*Du, J., Kerkhof, P., & van Koningsbruggen, G. M. (2021). The reciprocal relationships between social media self-control failure, mindfulness and wellbeing: A longitudinal study. PLoS One, 16(8), e0255648. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0255648

Duval, S., & Tweedie, R. (2000). Trim and fill: A simple funnel-plot–based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics, 56(2), 455–463. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0006-341X.2000.00455.x

Egger, M., Smith, G. D., Schneider, M., & Minder, C. (1997). Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ, 315(7109), 629–634. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629

*Eşkisu, M., Çam, Z., Gelibolu, S., & Rasmussen, K. R. (2020). Trait mindfulness as a protective factor in connections between psychological issues and Facebook addiction among Turkish university students. Studia Psychologica, 62(3), 213–231. https://doi.org/10.31577/sp.2020.03.801

Faber, R. J., & O’Guinn, T. C. (1992). A clinical screener for compulsive buying. Journal of Consumer Research, 19(3), 459–469. https://doi.org/10.1086/209315

Ferguson, C. J. (2015). Pay no attention to that data behind the curtain: On angry birds, happy children, scholarly squabbles, publication bias, and why betas rule metas. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(5), 683–691. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691615593353

*Gainza Perez, M. A. (2022). The protective influence of mindfulness facets on the relationship between negative core beliefs and social media addiction among latinx college students (Publication No. 29209062) [Masters Thesis, The University of Texas at El Paso]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.

Giluk, T. L. (2009). Mindfulness, Big Five personality, and affect: A meta-analysis. Personality and Individual Differences, 47(8), 805–811. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2009.06.026

Greco, L. A., Baer, R. A., & Smith, G. T. (2011). Assessing mindfulness in children and adolescents: Development and validation of the Child and Adolescent Mindfulness Measure (CAMM). 606–614. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022819

*Hassan, Y., & Pandey, J. (2021). Demystifying the dark side of social networking sites through mindfulness. Australasian Journal of Information Systems, 25. https://doi.org/10.3127/ajis.v25i0.2923

Higgins, J. P. T. (2008). Commentary: Heterogeneity in meta-analysis should be expected and appropriately quantified. International Journal of Epidemiology, 37(5), 1158–1160. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyn204

Hofmann, S. G., Sawyer, A. T., Witt, A. A., & Oh, D. (2010). The Effect of Mindfulness-Based Therapy on Anxiety and Depression: A Meta-Analytic Review., 78(2), 169–183. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018555

Hopwood, T. L., & Schutte, N. S. (2017). A meta-analytic investigation of the impact of mindfulness-based interventions on post traumatic stress. Clinical Psychology Review, 57, 12–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2017.08.002

Jermann, F., Billieux, J., Larøi, F., d'Argembeau, A., Bondolfi, G., Zermatten, A., & Van der Linden, M. (2009). Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS): Psychometric properties of the French translation and exploration of its relations with emotion regulation strategies. 21, 506–514. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017032

Kardefelt-Winther, D., Heeren, A., Schimmenti, A., van Rooij, A., Maurage, P., Carras, M., Edman, J., Blaszczynski, A., Khazaal, Y., & Billieux, J. (2017). How can we conceptualize behavioural addiction without pathologizing common behaviours? Addiction, 112(10), 1709–1715. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13763

Keles, B., McCrae, N., & Grealish, A. (2020). A systematic review: The influence of social media on depression, anxiety and psychological distress in adolescents. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 25(1), 79–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2019.1590851

Khoury, B., Lecomte, T., Fortin, G., Masse, M., Therien, P., Bouchard, V., ... & Hofmann, S. G. (2013). Mindfulness-based therapy: a comprehensive meta-analysis. Clinical psychology review, 33(6), 763–771. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0272735813000731?via%3Dihub

Kircaburun, K., Alhabash, S., Tosuntaş, ŞB., & Griffiths, M. D. (2020). Uses and gratifications of problematic social media use among university students: A simultaneous examination of the Big Five of personality traits, social media platforms, and social media use motives. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 18, 525–547. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-018-9940-6

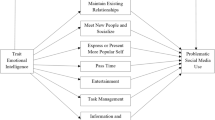

*Kircaburun, K., Griffiths, M. D., & Billieux, J. (2019). Trait emotional intelligence and problematic online behaviors among adolescents: The mediating role of mindfulness, rumination, and depression. Personality and Individual Differences, 139, 208-213.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2018.11.024

Kuss, D. J., & Griffiths, M. D. (2017). Social networking sites and addiction: Ten lessons learned. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(3), 311. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14030311

Li, W., Garland, E. L., McGovern, P., O’Brien, J. E., Tronnier, C., & Howard, M. O. (2017). Mindfulness-oriented recovery enhancement for internet gaming disorder in U.S. adults: A stage I randomized controlled trial. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 31, 393–402. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000269

Li, S. (2021). Psychological wellbeing, mindfulness, and immunity of teachers in second or foreign language education: a theoretical review. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 720340. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.720340

Liu, Q. (2019). Cumulative environmental risk and adolescent mobile phone addiction: The protective role of mindfulness [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Central China Normal University, Wuhan.

Liu, Q.-Q., Yang, X.-J., & Nie, Y.-G. (2022). Interactive effects of cumulative social-environmental risk and trait mindfulness on different types of adolescent mobile phone addiction. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-02899-1

Lundahl, O. (2021). Media framing of social media addiction in the UK and the US. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 45(5), 1103–1116. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12636

*Majeed, M., Irshad, M., Fatima, T., Khan, J., & Hassan, M. M. (2020). Relationship between problematic social media usage and employee depression: A moderated mediation model of mindfulness and fear of COVID-19. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.557987

Marino, C., Gini, G., Vieno, A., & Spada, M. M. (2018). The associations between problematic Facebook use, psychological distress and well-being among adolescents and young adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 226, 274–281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.10.007

Page, M. J., Moher, D., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., ... & McKenzie, J. E. (2021). PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n160

Reb, J., Allen, T., & Vogus, T. J. (2020). Mindfulness arrives at work: Deepening our understanding of mindfulness in organizations. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 159, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2020.04.001

Rosenthal, A., Levin, M. E., Garland, E. L., & Romanczuk-Seiferth, N. (2021). Mindfulness in treatment approaches for addiction — Underlying mechanisms and future directions. Current Addiction Reports, 8(2), 282–297. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-021-00372-w

Schutte, N. S., & Malouff, J. M. (2014). A meta-analytic review of the effects of mindfulness meditation on telomerase activity. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 42, 45–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.12.017

Schutte, N. S., Malouff, J. M., & Keng, S.-L. (2020). Meditation and telomere length: A meta-analysis. Psychology & Health, 35(8), 901–915. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2019.1707827

Serenko, A., & Turel, O. (2015). Integrating technology addiction and use: An empirical investigation of Facebook users. AIS Transactions on Replication Research, 1(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.17705/1atrr.00002

Sommers-Spijkerman, M., Austin, J., Bohlmeijer, E., & Pots, W. (2021). New evidence in the booming field of online mindfulness: An updated meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JMIR Mental Health, 8(7), e28168. https://doi.org/10.2196/28168

*Sriwilai, K., & Charoensukmongkol, P. (2016). Face it, don't Facebook it: Impacts of social media addiction on mindfulness, coping strategies and the consequence on emotional exhaustion. Stress and Health, 32(4), 427-434.https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2637

Sun, Y., & Zhang, Y. (2021). A review of theories and models applied in studies of social media addiction and implications for future research. Addictive Behaviors, 114, 106699. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106699

*Throuvala, M. A., Griffiths, M. D., Rennoldson, M., & Kuss, D. J. (2020). Mind over matter: Testing the efficacy of an online randomized controlled trial to reduce distraction from smartphone use. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(13), 4842.https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17134842

Tomlinson, E. R., Yousaf, O., Vittersø, A. D., & Jones, L. (2018). Dispositional mindfulness and psychological health: A systematic review. Mindfulness, 9(1), 23–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-017-0762-6

*Turel, O., & Osatuyi, B. (2017). A peer-influence perspective on compulsive social networking site use: Trait mindfulness as a double-edged sword. Computers in Human Behavior, 77, 47-53.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.08.022

van den Eijnden, R. J. J. M., Lemmens, J. S., & Valkenburg, P. M. (2016). The Social Media Disorder Scale. Computers in Human Behavior, 61, 478–487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.03.038

Walsh, J. (2020). Social media and moral panics: Assessing the effects of technological change on societal reaction. International Journal of Cultural Studies. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367877920912257

Wang, Y., Derakhshan, A., & Zhang, L. J. (2021). Researching and practicing positive psychology in second/foreign language learning and teaching: the past, current status and future directions. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 731721. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.731721

Wartberg, L., Kriston, L., & Thomasius, R. (2020). Internet gaming disorder and problematic social media use in a representative sample of German adolescents: Prevalence estimates, comorbid depressive symptoms and related psychosocial aspects. Computers in Human Behavior, 103, 31–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.09.014

*Weaver, J. L., & Swank, J. M. (2021). An examination of college students’ social media use, fear of missing out, and mindful attention. Journal of College Counseling, 24(2), 132-145.https://doi.org/10.1002/jocc.12181.

Weaver, J. L., & Swank, J. M. (2019). Mindful connections: A mindfulness-based intervention for adolescent social media users. Journal of Child and Adolescent Counseling, 5(2), 103–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/23727810.2019.1586419

Weaver, J. L. (2021). A mindfulness-based intervention for adolescent social media users: A quasi-experimental study (Publication No. 28319126) [Doctoral dissertation, University of Florida]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.

Wong, H. Y., Mo, H. Y., Potenza, M. N., Chan, M. N. M., Lau, W. M., Chui, T. K., Pakpour, A. H., & Lin, C.-Y. (2020). Relationships between severity of Internet gaming disorder, severity of problematic social media use, sleep quality and psychological distress. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(6), 1879. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17061879

Xanidis, N., & Brignell, C. M. (2016). The association between the use of social network sites, sleep quality and cognitive function during the day. Computers in Human Behavior, 55, 121–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.09.004

Yao, Y.-W., Chen, P.-R., Li, C.-S.R., Hare, T. A., Li, S., Zhang, J.-T., Liu, L., Ma, S.-S., & Fang, X.-Y. (2017). Combined reality therapy and mindfulness meditation decrease intertemporal decisional impulsivity in young adults with Internet gaming disorder. Computers in Human Behavior, 68, 210–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.11.038

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval statement and informed consent

This study reports the results of a meta-analysis, thus ethics approval and informed consent are not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Meynadier, J., Malouff, J.M., Loi, N.M. et al. Lower Mindfulness is Associated with Problematic Social Media Use: A Meta-Analysis. Curr Psychol 43, 3395–3404 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04587-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04587-0