Abstract

Parental duties can be overwhelming, particularly when parents lack sufficient resources to cope with parenting demands, leading to parental burnout. Research has shown that parental burnout is positively related to neglect and abuse behaviors towards their children; however, few studies have examined parental burnout within the family system, including examining parenting styles as an antecedent, and most research has ignored the potential influence of fathers’ parental burnout. This study aimed to explore the influence of fathers’ parenting stress and parenting styles on internalizing and externalizing problem behaviors in a sample of junior high school students and the mediating effect of parental burnout. Questionnaire data from 236 students (56.4% girls) and their fathers (age: M = 39.24, SD = 5.13) were collected on 3 different time points. Fathers were asked to report their parenting stress and parenting styles at Time 1, and parental burnout at Time 2, and students were asked to report their internalizing and externalizing behaviors at Time 3. The results indicated that: (1) fathers’ parenting stress and negative parenting styles were positively related to parental burnout, and fathers’ positive parenting styles were negatively related to parental burnout; (2) fathers’ parental burnout was positively related to children’s internalizing and externalizing problem behavior; and (3) fathers’ parental burnout could mediate the relationship between parenting stress, negative parenting styles, and internalizing and externalizing problem behavior. These results suggested that fathers’ roles in the parenting process were not negligible, and more attention should be given to prevention and intervention methods for fathers’ parental burnout.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

When parents lack the resources needed to handle stressors related to parenting, they may develop parental burnout (Mikolajczak & Roskam, 2018). Parental burnout refers to a variety of negative symptoms, such as emotional exhaustion, emotional alienation from children, and decreased parenting efficacy (Roskam et al., 2017). Recently, parental burnout has been extensively studied by numerous researchers in over 40 countries (Roskam et al., 2021). Existing researches has primarily focused on its measurement (e.g., Cheng et al., 2020; Kawamoto et al., 2018; Szczygieł et al., 2020), and antecedents (e.g., Brianda et al., 2020; Sorkkila & Aunola, 2020). However, there are still several limitations of study on parental burnout.

First, as empirical research on parental burnout was not conducted until Roskam et al. (2018) proposed the measurement of parental burnout, studies on the antecedents of parental burnout remain insufficient. Based on the conception of parental burnout (Mikolajczak & Roskam, 2018), an important antecedent variable of parental burnout is parenting stress. However, the relationship between parental burnout and parenting stress are generally accepted and still need more empirical research to support. Second, another important antecedent may be the parenting styles. As parenting styles are embodied in all aspects of parenting activities, and different parenting styles might result different parenting experiences (Crnic & Coburn, 2021). However, to our best knowledge, there was only one study preliminarily explored the relationship between parenting style and burnout (Mikkonen et al., 2022). therefore, the relationship between parenting styles and parental burnout remains to be further discussed. Third, prior studies related the consequences of parental burnout mainly focused on the effects on parents themselves (Mikolajczak & Roskam, 2020), pay relatively less attention to the direct effects of parental burnout on children (Chen et al., 2021). Considering the aim of parenting is healthy development of their children, more researches are needed to explore the relationship between parental burnout and children’ development. One of the important indicators of mental health was problem behavior, whereas there was only one prior study examined the effect of parental burnout on problem behavior (e.g., Chen et al., 2021). Therefore, the relationship between parental burnout and problem behavior of their children needs to be further discussed.

In addition, previous studies mainly focused on mothers’ parental burnout, and thus most of the samples consisted of mothers only (Chen et al., 2021; Lebert-Charron, et al., 2021). Moreover, even if the studies contained both fathers and mothers, most of them combined fathers and mothers into one sample (e.g., LeVigouroux-Nicolas, et al., 2017; Sorkkila & Aunola, 2020). However, as fathers have become increasingly more involved in parenting (e.g., Xie et al., 2021), more attention should be paid to fathers’ parental burnout.

Above all, to address these gaps, this study aimed to examine the relationships between fathers’ parenting stress, parenting styles, and parental burnout, and the mediating effects of parental burnout were also examined.

Parenting stress and parental burnout

Parenting stress is conceptualized as a form of stress experienced by parents during childrearing (Kochanova et al., 2021). In fact, parenting can be one of the most taxing jobs one undertakes (Mikolajczak et al., 2019). From birth on, children can put their parents under considerable stress (e.g., Crnic & Low, 2002). According to the balance between risks and resources theory (BR2; Mikolajczak & Roskam, 2018), parental burnout occurs when parents in chronic parenting stress and do not have sufficient resources to cope. Therefore, the parenting stress is an important antecedent of parental burnout, However, due to the empirical research of parental burnout did not been conducted until recently, empirical studies directly focused on the relationship between parenting stress and parental burnout are still not enough. Based on this, hypothesis 1 was proposed.

-

Hypothesis 1: Fathers’ parenting stress would positively predict parental burnout.

Parenting styles and parental burnout

Parenting styles refer to constellations of parental attitudes and behaviors toward children, which create a general emotional climate for parent–child interaction and parental socialization (Darling & Steinberg, 1993). Parenting styles play a profound and long-lasting role in children’s development (Marcone et al., 2020), with different parenting styles resulting in different parenting experiences (Crnic & Coburn, 2021). According to BR2 theory, positive parenting styles could be related to the gain of parenting resources, and negative parenting styles could be related to the depletion of parenting resources (Mikolajczak & Roskam, 2018).

Influenced by the traditional familial conception of a “loving mother, strict father” rooted in early Chinese patriarchal society (Ling, 2019), fathers in China tend to adopt harsh parenting behaviors, such as authoritative control, restriction, and interference towards their children (Marcone et al., 2020). Such parenting behaviors may cause children to form anxious or avoidant parent–child attachments, which, in turn, can lead to increases in fathers’ stress reactions (Smyth et al., 2015), inefficient parenting styles (Adam et al., 2004), poor parent–child relationships (Holstein et al., 2021), and reduce fathers’ parenting self-efficacy (Mikolajczak et al., 2018b; Roskam & Mikolajczak, 2021); thus, increasing the risks of parental burnout (Cheng et al., 2020; Mikolajczak et al., 2019). In contrast, positive parenting styles may result in healthy parent–child relationships, a warm and loving family atmosphere, and increased parenting self-efficacy among fathers (Mikolajczak et al., 2018b; Roskam & Mikolajczak, 2021). Furthermore, positive parenting styles are associated with decreased perceptions of role limitations and the presence of external resources to cope with parenting risk factors, which may result in decreased burnout (Marcone et al., 2020; Roskam & Mikolajczak, 2021; Zhang et al., 2019). In view of research has demonstrated that parenting styles affect parenting demands and resources (Mikolajczak et al., 2018b) and parental burnout result from the unbalance of parenting demands and resources. Therefore, hypothesis 2 was proposed.

-

Hypothesis 2: Fathers’ negative parenting styles would positively predict parental burnout, while positive parenting style would negative predict parental burnout.

Parental burnout and problem behaviors

Problem behaviors are defined as abnormal behaviors, with severity and duration beyond the age range permitted by social moral norms, which can be divided into internalizing problem behaviors and externalizing problem behaviors (Achenbach, 1991). Externalizing problem behaviors are those behaviors that are destructive, including aggression and skipping classes (Kovacs & Devlin, 1998), where negative emotions are directed toward others (Campbell et al., 2000; Roeser et al., 1998) whereas internalizing problem behaviors are related to anxiety and mood disorders, including depression, anxiety, and withdrawal (Eisenberg et al., 2001; Roeser et al., 1998), such that negative emotions are directed inward, rather than toward others (Roeser et al., 1998).

According to family system theory, family members are influenced each other (Bowen, 1976). parental burnout may occur in the family system and its negative effects may go beyond themselves and spill over to parent–child systems. Therefore, Parental burnout could be an antecedent of adolescents’ problem behaviors (Chen et al., 2021). Previous studies have shown that parental burnout can increase conflict between couples (Mikolajczak & Roskam, 2020), and adolescents’ exposure to spousal conflicts may increase both their internalizing (Philbrook et al., 2018; Xuan et al., 2018), and externalizing problems (Peng et al., 2021; Petersen et al., 2015). Furthermore, parental burnout can increase parental neglect and abuse (Brianda et al., 2020; Mikolajczak et al., 2019; Sorkkila & Aunola, 2020). Parental neglect has been identified as a risk factor for adolescents’ delinquency (Mak, 1994) and can predict adolescents’ internalizing problems (Tirfeneh & Srah, 2019), withdrawal (Choi et al., 2020), and psychological disorders (Sajid & Shah, 2021). In addition, parental violence can predict adolescents’ post-traumatic stress disorder (Haj-Yahia et al., 2019), decrease adolescent self-control (Willems et al., 2018), and increase the likelihood of adolescents being aggressive or victimized (Davis et al., 2020; Xia et al., 2018). In view of prior studies have supported the prediction of parental burnout on adolescents’ problem behaviors (e.g., Chen et al., 2021). Therefore, hypothesis 3 was proposed.

-

Hypothesis 3: Fathers’ parental burnout would positively predict children’s internalizing and externalizing problem behaviors.

Mediating effect of parental burnout

As noted above, based on the BR2 theory (Mikolajczak & Roskam, 2018), parenting stress and parenting styles could be associated with parental burnout. Simultaneously, according to family system theory (Bowen, 1976), fathers’ parental burnout could be associated with adolescents’ problem behavior. In addition, prior studies have shown that Fathers’ parenting stress could increase the risk of their children’s externalizing (Barroso et al., 2018; Silinskas et al., 2020) or internalizing problems (Silinskas et al., 2020). And the negative parenting styles are closely related to children’s active or passive violent behavior (Ong et al., 2018) and aggressive behavior (Russ et al., 2003). However, when parents adopt positive parenting styles, the democratic and harmonious family atmosphere provides children with additional resources, and their children have a decreased likelihood of problematic behaviors (Skinner et al., 2022). With the combination of BR2 theory (Mikolajczak & Roskam, 2018) and family system theory (Bowen, 1976), taken Hypotheses 1–3 together, hypotheses 4 and 5 were proposed:

-

Hypothesis 4: Parental burnout would mediate the relationship between parenting stress and problem behaviors.

-

Hypothesis 5: The relationship between parenting style and problem behavior would be mediated by parental burnout.

The present study

The present study aimed to examine how fathers’ parenting stress and parenting styles are associated with their children’s problem behaviors as well as the mediating effect of parental burnout in a sample of junior high school students and their fathers. The present study selected a sample of junior high school students and their fathers for several reasons. First, junior high school students are in their adolescence, a development stage that involves autonomy seeking and engaging in rebellious behaviors (Crnic & Coburn, 2021). Further, when children enter adolescence, most parents experience increased stress, uncertainty, and vulnerability, resulting in increased parenting stress (Crnic & Coburn, 2021).

Existing literature on parental burnout has primarily focused on mothers (e.g., Chen et al., 2021; Meeussen & Laar, 2018), resulting in parental burnout among fathers receiving insufficient attention. In traditional Chinese culture, there is a well-known saying— “If a son is uneducated, his dad is to blame,” emphasizing the importance of fathers’ role in their children’s education (Gao & Zhang, 2021). With societal progress, the traditional Chinese family division model of “men work outside, women do the housework at home” has also changed (Wang et al., 2021a), and fathers have become increasingly involved in the parenting activities of their children. Therefore, this study targeted a sample of fathers. The framework of the present study is shown in Fig. 1.

Methods

Participants and procedures

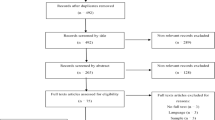

The current study included 455 seven-grade students and their fathers from a middle school in Henan Province as participants, and the data were collected on three separate occasions with an interval of 15 days. Participants were told that the study aimed to examine “work and study conditions.” Fathers were asked to report their parenting stress and parenting styles at Time 1 and parental burnout at Time 2, and students were asked to report their internalizing and externalizing behaviors at Time 3. The investigator distributed questionnaires to the students who were also asked to deliver the questionnaires to their fathers at home. When the fathers completed their questionnaires, the students returned the questionnaires to the investigators in their school. In the third round of data collection, students were asked to complete a questionnaire during class. Both the fathers and students were asked to provide the last four digits of the father’s phone number, which was used to match the three sets of questionnaire data.

In the first round of data collection, 455 fathers completed the survey; in the second round, 417 fathers completed the survey; and in the third round, 375 students completed the survey. In total, 236 paired data points were matched. Fathers had a mean age of 39.24 years (SD = 5.13), with 166 having a high school education or less and 70 having a bachelor’s degree or higher. The sample of students included 133 girls (56.4%) and 103 boys (43.6%).

Meanwhile, the G*power was used to calculate the minimum sample size needed for the hypothesized model. The effect size ƒ2 was set at 0.15, significant level (α) was set at 0.05, the power at 0.95, then inputting number of our tested predictors 4 and total number of predictors 4. The result showed that 129 samples were needed to validate hypotheses of this study, which means that 236 samples that enrolled in our study met the requirement of sample size for data analysis.

Measures

Parenting stress

Parenting stress was measured using the Chinese version of the Parenting Stress Index-Short Form (Abidin, 1990; Ren, 1995), consisting of 36 items. Each item was rated using a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), with a higher score representing higher stress levels. An example item was, “Since I have had this child, I have been unable to do other new things.” The Cronbach’s α in the current study was 0.90.

Parenting styles

Parenting style was measured using the Parenting Styles Questionnaire (Li & Xu, 2001) that consisted of 75 items measured on four dimensions: Negative Parenting Behavior, Positive Parenting Behavior, Family Atmosphere, Educational Expectations, and Confusion. In this study, only two dimensions, including 54 items, were examined: Negative Parenting Behavior (e.g., “I often threaten my child when s/he does something wrong”) and Positive Parenting Behavior (e.g., “When the child does something wrong, I patiently express my true thoughts in a reasonable way”). Each item was rated on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (completely inconsistent) to 5 (completely consistent). In this study, the Cronbach’s α coefficients for positive and negative parenting styles were 0.88 and 0.86, respectively.

Parental burnout

Parental burnout was measured using the Chinese short version of the Parental Burnout Assessment (s-PBA; Wang et al., 2021b). It consisted of seven items, and each item was rated using a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (completely inconsistent) to 7 (completely consistent), with a higher score representing higher burnout. An example was, “I feel as though I’ve lost my direction as a dad/mom.” For the current sample, the Cronbach’s α was 0.85.

Internalizing and externalizing problems

Internalizing and externalizing problem behaviors were measured using the subscale of the Chinese version of the Youth Self-Report (YSR; Achenbach, 1991; Wang et al., 2005). The original questionnaire consists 8 factor with 112 items. In the present study, internalizing (e.g., “I often cry.”) and externalizing (e.g., “I often fight.”) problem behaviors included 53 items that were measured. The questionnaire consists of 53 items, each rated on a 3-point scale ranging from 0 (never) to 2 (often), with higher scores representing higher levels of problem behaviors. In this study, the Cronbach’s α coefficients for the internalizing and externalizing scales were 0.84 and 0.82, respectively.

Data analysis

The data were analyzed in detail using SPSS 22.0 and AMOS 24.0. First, common method bias and missing data were analyzed. Second, descriptive statistics and a correlation matrix are calculated. Third, a structural equation model (SEM) analysis was conducted to calculate the path coefficients between the variables, and the bootstrap mediating effects procedure was used to test the mediating effects of fathers’ parental burnout on parenting stress, parenting styles, and problem behaviors. Evaluation of model fit was assessed using inferential goodness-of-fit statistics (χ2) and several other indices, including the comparative fit index (CFI), tucker-lewis coefficien (TLI), normed fit index (NFI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and standardized root mean squared residual (SRMR). Values close to or greater than 0.95 are desirable on the CFI, TLI, and NFI, while the RMSEA and SRMR should preferably be less than or equal to 0.08 (Hu & Bentler, 1999; MacCallum et al., 1996). Point estimates of the indirect effects and 95% confidence intervals for the effects were calculated using a bootstrapping method with 5000 samples (Preacher et al., 2007).

In addition, when we checked the distribution of the data, parental burnout scores did not show a normal distribution. In accordance with a prior study (Mikolajczak et al., 2018a), the PBA scores were normalized by log transformations (skewness = 1.995 and kurtosis = 3.875). When the correlation analysis was conducted with the transformed scores, there were no significant differences between the results of the transformed scores and the original ones, so we reported the results of the original scores.

Results

Common method bias

Harman’s one-way test was used to test for common method bias, and all items used in the questionnaire in the study were put together for exploratory factor analysis, including parental burnout, parenting styles, parenting stress, and problem behavior questionnaires. The results showed 46 initial eigenvalues greater than 1, and the maximum factor variance explained was 12.64% (less than 40%), so there was no common method bias problem in this study.

Missing data analysis

Before conducting the hypothesis testing, Welch’s test was conducted between participants who completed the questionnaire and those who dropped out. There were no significant differences between fathers’ age (t = -0.81, df = 446.81, p = 0.42), fathers’ education level (t = -0.78, df = 452.92, p = 0.44), and students’ gender (t = -1.21, df = 449.89, p = 0.23). These results suggest that removing incomplete questionnaires did not bias our result significantly.

Descriptions and correlations

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics and Pearson’s correlations of all variables. Parenting stress was positively correlated with parental burnout (r = 0.31, p = 0.000). Negative parenting styles were also positively correlated with parental burnout (r = 0.26, p = 0.000), while positive parenting styles were negatively correlated with parental burnout (r = -0.23, p = 0.000). In addition, parental burnout was positively correlated with internalizing (r = 0.32, p = 0.000) and externalizing problem behaviors (r = 0.19, p = 0.003).

Hypotheses testing of SEM

Parenting stress and parenting style were the independent variables in the path analysis, with internalizing and externalizing problem behaviors as dependent variables. Parental burnout was an intermediary variable to create an SEM to test the study hypotheses. The model fit the data well: χ 2 = 3.9, p = 0.000, CFI = 1.000 > 0.95, NFI = 0.987 > 0.95, TLI = 1.019 > 0.95, RMSEA = 0.000 < 0.08, SRMR = 0.02 < 0.08 (Hu & Bentler, 1999; MacCallum et al., 1996). The results of path analysis are presented in Table 2.

As shown in Table 2, parenting stress had a positive predictive effect on parental burnout (β = 0.22, p = 0.001). Thus, hypothesis 1 was supported. Both negative parenting styles (β = 0.12, p = 0.086) and positive parenting styles (β = -0.11, p = 0.088) had a marginally significant effect on parental burnout, indicating that negative and positive parenting styles were predictors of parental burnout. Thus, hypothesis 2 was supported. Parental burnout was also a significant positive predictor of internalizing (β = 0.32, p = 0.000) and externalizing behavior problems (β = 0.19, p = 0.002). Thus, hypothesis 3 was supported.

Parental burnout had a mediating effect on the relationship between fathers’ parenting stress and students’ problem behaviors, with significant indirect effects (Internalizing: β = 0.03, p = 0.007, 95% CI [0.011, 0.065]; Externalizing: β = 0.01, p = 0.007, 95% CI [0.003, 0.035]). Thus, hypothesis 4 was supported. Moreover, the mediating effects of parental burnout in the relationship between fathers’ negative parenting styles and students’ problem behaviors were significant (Internalizing: β = 0.02, p = 0.023, 95% CI [0.003, 0.062]; Externalizing: β = 0.01, p = 0.024, 95% CI [0.001, 0.032]). However, the relationship between fathers’ positive parenting styles and students’ problem behaviors were not mediated by fathers’ parental burnout as the mediating effect was not significant (Internalizing: β = -0.02, p = 0.076, 95% CI [-0.059, 0.002]; Externalizing: β = -0.01, p = 0.084, 95% CI [-0.027, 0.001]). Therefore, hypothesis 5 was partially supported. The results are shown in Fig. 2.

Result of analyzed model. Notes: χ2 = 3.9, p = 0.000, CFI = 1.000 > 0.95, NFI = 0.987 > 0.95, TLI = 1.019 > 0.95, RMSEA = 0.000 < 0.08, SRMR = 0.02 < 0.08, Dark arrows indicate the significant hypothesized paths. Faded double-curved arrows signify concurrent associations between the variables. †p < 0.10, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001. The path coefficients are standardized

Discussion

When individuals experience chronic and overwhelming parenting stress (Mikolajczak et al., 2019) or use inappropriate parenting styles (Mikolajczak et al., 2018b), they may develop parental burnout. Burned-out parents are at increased risk for neglect and violence toward their children (Mikolajczak et al., 2018a), leading to internalizing and externalizing problems behavior in children (Beckmann, 2021). This study aimed to examine how fathers’ parenting stress and parenting styles are associated with children’s problem behaviors through the mediating effect of parental burnout within a sample of junior high school students and their fathers. Overall, the results generally supported our hypotheses.

Parenting stress and parenting style were found to predict parental burnout over time, consistent with previous research. The risk of parental burnout has been shown to increase when fathers’ parenting stress exceeds their coping resources (Mikolajczak & Roskam, 2020; Mikolajczak et al., 2019). Fathers who are influenced by the traditional culture of Chinese fathers as “the head of the family” may be likely to have harsh parenting styles, such as authoritative control. Thus, they have problems with listening to their children, impairing the parent–child relationship, which in turn, increases feelings of burnout (Holstein et al., 2021). In contrast, fathers who implement positive parenting styles are likely to form good parent–child relationships (Skinner et al., 2022), improve their parenting self-efficacy, and reduce the likelihood of parental burnout (Mikolajczak & Roskam, 2020).

Moreover, our results indicated that parental burnout had predictive effects on students’ internalizing and externalizing problem behaviors. Junior high school students are already at increased risk for problem behaviors (Crnic & Coburn, 2021); fathers, as one of the closest to their children (Silinskas et al., 2020), can directly influence their adolescents’ internal or external problem behaviors when they are experiencing parental burnout (Mikolajczak et al., 2019; Roskam et al., 2018). The negative influence of fathers’ parental burnout on children can be sizable; therefore, researchers should pay attention to fathers to detect, prevent, and intervene when they experience parental burnout (Yu, 2021).

The mediating role of parental burnout was also identified. Fathers experience parental burnout when they face chronic parenting stress due to the excessive demands placed on them by parenting activities (Meeussen & Laar, 2018; Mikolajczak et al., 2018b), a lack of spousal support (Mikolajczak et al., 2018b), low family income (Kawamoto et al., 2018), parent–child tension (Yu, 2021), and difficulty maintaining healthy parent–child relationships due to negative parenting styles (Gong, 2020). This creates a sense of frustration relating to parenting and a gradual dislike in their role as a father (Mikolajczak et al., 2019). Fathers who are burned out may alienate their children (Mikolajczak et al., 2018a). Adolescence is a period of higher incidence of problem behaviors, when adolescents realize that their previously intimate father is distancing themselves, which may harm their parent–child relationship and lead to self-doubt and internalizing problems in adolescents, such as depression and withdrawal (Shen et al., 2021). Prior studies have found that parents experiencing burnout also engage in violent behaviors toward their children in their daily parenting activities (Mikolajczak et al., 2018a). Adolescents may have greater self-esteem than they had in childhood, and their fathers’ violent behavior may increase their rebellious behavior, resulting in increased problem behaviors (Ding, 2020). Thus, fathers’ parenting stress and negative parenting styles may indirectly affect students’ internalizing and externalizing problem behaviors through fathers’ parental burnout.

Theoretical implications

This study explored the factors influencing fathers’ parental burnout and examined the potential sequelae of their parental burnout on adolescents in the Chinese cultural context. It may also expand the field’s understanding of fathers’ parental burnout (Mikolajczak et al., 2019), enriching the research about the relationship between parental burnout and children’s problem behaviors and providing a new understanding of the negative effect of parental burnout on children’s development.

Previous parenting research has been primarily concerned with mothers (e.g., Chen et al., 2021; Hubert & Aujoulat, 2018). However, fathers’ involvement in parenting is essential for their children’s development (Gao & Zhang, 2021). This study’s focus on the relationships between parental burnout and parenting stress, parenting styles, and problem behaviors from the perspective of fathers provides theoretical and practical basis for identifying pathways to problem behaviors among children.

Practical implications

The present study provided further evidence of the importance of fathers in child-rearing. Fathers need to recognize their own parental burnout and their children’s problem behaviors and need to be aware of the effects of their own parental burnout (Roskam et al., 2018; Sorkkila & Aunola, 2020), parenting stress (Silinskas et al., 2020), and parenting styles (Ong et al., 2018; Skinner et al., 2022) on their children’s development. Fathers should be supported so they can recognize their own parenting challenges and make appropriate, timely adjustments. Fathers also need to learn how to cope with their own stress, treat their children with positive and supportive attitudes, and develop good parent–child relationships (Yu, 2021).

Limitations and future directions

This study provided new evidence on fathers’ parental burnout within the Chinese cultural context; however, some limitations should be noted. First, the present study used a convenience sample that included only seventh-grade students and their fathers from one middle school in central China, without involving groups from other regions and grades; thus, it is unclear whether these findings can be universally generalized. Therefore, future studies should expand the sampling regions and grades and evaluate our hypothesized model with samples from different backgrounds to verify the universality of our research conclusions.

Further, this study only examined fathers’ parenting styles as two broad constructs of positive and negative parenting styles. However, some researchers indicated that parenting styles are not limited to the positive and negative styles (e.g., Maccoby & Martin, 1983). Different parenting styles may have different influences on both parents and their children (Beckmann, 2021; Marcone et al., 2020). Thus, future research should examine the relationship between parenting styles, parental burnout, and children's problem behaviors in greater depth with more refined parenting styles.

Finally, despite our study collected data in different times to avoid common method bias (Podsakoff et al., 2003), and matched fathers’ and adolescent’ answer in statistical analysis, our study was not a longitudinal design. Future research could adopt a more logical justification design, such as collecting the total variable measure as baseline data for the first time, and a potential growth model, or a cross-lagged model could be adopted in statistical analysis to infer the causal relationship among variables.

Conclusions

This study makes a valuable contribution to the field’s understanding of the development of parental burnout among fathers and its effects on their children. Specifically, the results indicated that fathers’ parenting stress and negative parenting styles could affect their parental burnout over time, predicting their children’s internalizing and externalizing problem behaviors. These findings underscore the importance of recognizing that fathers’ negative behaviors and attitudes toward parenting have adverse effects on fathers themselves but could also harm their children’s physical and mental health.

Data availability

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

References

Abidin, R. R. (1990). Parenting Stress Index (PSI). Pediatric Psychology Press.

Achenbach, T. M. (1991). Manual for the self-report and 1991 YSR profile. University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry.

Adam, E. K., Gunnar, M. R., & Tanaka, A. (2004). Adult attachment, parent emotion, and observed parenting behavior: Mediator and moderator models. Child Development, 75(1), 110–122. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00657.x

Barroso, N. E., Mendez, L., Graziano, P. A., & Bagner, D. M. (2018). Parenting stress through the lens of different clinical groups: A systematic review & meta-analysis. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 46(3), 449–461. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-017-0313-6

Beckmann, L. (2021). Does parental warmth buffer the relationship between parent-to-child physical and verbal aggression and adolescent behavioural and emotional adjustment? Journal of Family Studies, 27(3), 366–387. https://doi.org/10.1080/13229400.2019.1616602

Bowen, M. (1976). Theory in the practice of psychotherapy. Family Therapy: Theory and Practice, 4(1), 2–90.

Brianda, M. E., Roskam, I., Gross, J. J., Franssen, A., Kapala, F., Gérard, F., & Mikolajczaka, M. (2020). Treating parental burnout: Impact of two treatment modalities on burnout symptoms, emotions, hair cortisol, and parental neglect and violence. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 89(5), 330–332. https://doi.org/10.1159/000506354

Campbell, S. B., Shaw, D. S., & Gilliom, M. (2000). Early externalizing behavior problems: Toddlers and preschoolers at risk for later maladjustment. Development and Psychopathology, 12(3), 467–488. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.105.4.518

Chen, B.-B., Qu, Y., Yang, B., & Chen, X. (2021). Chinese mothers’ parental burnout and adolescents’ internalizing and externalizing problems: The mediating role of maternal hostility. Developmental Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0001311

Cheng, H., Wang, W., Wang, S., Li, Y., Liu, X., & Li, Y. (2020). Validation of a Chinese Version of the Parental Burnout Assessment. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 321–331. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00321

Choi, O., Choi, J., & Kim, J. (2020). A longitudinal study of the effects of negative parental child-rearing attitudes and positive peer relationships on social withdrawal during adolescence: An application of a multivariate latent growth model. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 25(1), 448–463. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2019.1670684

Crnic K, & Low C (2002). Everyday stresses and parenting. In M. F. Bornstein (Ed.), Handbook of parenting. Volume 5: practical issues in parenting (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Crnic, K. A., & Coburn, S. S. (2021). Stress and parenting. In M. H. Bornstein (Ed.), Psychological insights for understanding COVID-19 and families, parents, and children (pp. 103–130). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

Darling, N., & Steinberg, L. (1993). Parenting style as context: An integrative model. Psychlogical Bulletin, 113(3), 487–496. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.113.3.487

Davis, J. P., Ingram, K. M., Merrin, G. J., & Espelage, D. L. (2020). Exposure to parental and community violence and the relationship to bullying perpetration and victimization among early adolescents: A parallel process growth mixture latent transition analysis. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 61(1), 77–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12493

Ding, X. (2020). A study on the relationship between problem behavior of high-grade primary school students, parenting style and parent-child relationship [Unpublished master’s thesis]. Southwest University.

Eisenberg, N., Cumberland, A., Spinrad, T. L., Fabes, R. A., Shepard, S. A., Reiser, M., Murphy, B. C., Losoya, S. H., & Guthrie, I. K. (2001). The relations of regulation and emotionality to children’s externalizing and internalizing problem behavior. Child Development, 72(4), 1112–1134. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00337

Gao, S., & Zhang, B. (2021). A study on the relationship between fatherhood and social communication ability of middle school students. Education and Teaching Research, 35(11), 104–117. https://doi.org/10.13627/j.cnki.cdjy.2021.11.009 (In Chinese).

Gong, Y. (2020). An empirical study on the influence of parenting style on parent-child relationship: Based on the data of China Education Tracking Survey. Mental Health Education in Primary and Secondary Schools, 28, 24–27. (In Chinese).

Haj-Yahia, M. M., Sokar, S., Hassan-Abbas, N., & Malka, M. (2019). The relationship between exposure to family violence in childhood and post-traumatic stress symptoms in young adulthood: The mediating role of social support. Child Abuse & Neglect, 92, 126–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.03.023

Holstein, B. E., Pant, S. W., Ammitzbøll, J., Laursen, B., Madsen, K. R., Skovgaard, A. M., & Pedersen, T. P. (2021). Parental education, parent-child relations and diagnosed mental disorders in childhood: Prospective child cohort study. European Journal of Public Health, 31(3), 514–520. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckab053

Hu, L.-T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Hubert, S., & Aujoulat, I. (2018). Parental burnout: When exhausted mothers open up. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, Article 1021. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01021

Kawamoto, T., Furutani, K., & Alimardani, M. (2018). Preliminary Validation of Japanese Version of the Parental Burnout Inventory and Its Relationship With Perfectionism. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, Article 970. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00970

Kochanova, K., Pittman, L. D., & McNeela, L. (2021). Parenting stress and child externalizing and internalizing problems among low-income families: Exploring transactional associations. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 53(1), 76–88. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-020-01115-0

Kovacs, M., & Devlin, B. (1998). Internalizing disorders in childhood. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 39(1), 47–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-7610.00303

Le Vigouroux, S., Scola, C., Raes, M.-E., Mikolajczak, M., & Roskam, I. (2017). The big five personality traits and parental burnout: Protective and risk factors. Personality and Individual Differences, 119, 216–219.

Lebert-Charron, A., Wendland, J., Vivier-Prioul, S., Boujut, E., & Dorard, G. (2021). Does perceived partner support have an impact on mothers’ mental health and parental burnout? Marriage & Family Review, 1–21,. https://doi.org/10.1080/01494929.2021.1986766

Li, Y., & Xu, D. (2001). Preparation and trial of questionnaires on parenting styles. Journal of the Third Military Medical University, 12, 1494–1495. (In Chinese).

Ling, L. (2019). An analysis on the problem of “Parental Consistency” in early childhood family education. Intellect, 14, 134. (In Chinese).

MacCallum, R. C., Browne, M. W., & Sugawara, H. M. (1996). Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychological Methods, 1(2), 130–149. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.1.2.130

Maccoby, E., & Martin, J. (1983). Socialization in the context of the family: Parent-child interaction. Handbook of Child Psychology, Vol. 4 Socialization, Personality, and Social Development, 4, 1–101.

Mak, A. S. (1994). Parental neglect and overprotection as risk factors in delinquency. Australian Journal of Psychology, 46(2), 107–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049539408259481

Marcone, R., Affuso, G., & Borrone, A. (2020). Parenting styles and children’s internalizing-externalizing behavior: The mediating role of behavioral regulation. Current Psychology, 39(1), 13–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-017-9757-7

Meeussen, L., & Laar, C. V. (2018). Feeling pressure to be a perfect mother relates to parental burnout and career ambitions. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, Article 2113. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02113

Mikkonen, K., Veikkola, H.-R., Sorkkila, M., & Aunola, K. (2022). Parenting styles of Finnish parents and their associations with parental burnout. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03223-7

Mikolajczak, M., Raes, M.-E., Avalosse, H., & Roskam, I. (2018b). Exhausted parents: Sociodemographic, child-related, parent-related, parenting and family-functioning correlates of parental burnout. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27(2), 602–614. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0892-4

Mikolajczak, M., Gross, J. J., & Roskam, I. (2019). Parental burnout: What is it, and why does it matter? Clinical Psychological Science, 7(6), 1319–1329. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702619858430

Mikolajczak, M., Brianda, M. E., Avalosse, H., & Roskam, I. (2018a). Consequences of parental burnout: Its specific effect on child neglect and violence. Child Abuse & Neglect, 80(1), 134–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.03.025

Mikolajczak, M., & Roskam, I. (2018). A theoretical and clinical framework for parental burnout: The balance between risks and resources (BR2). Frontiers in Psychology, 9, Article 886. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00886

Mikolajczak, M., & Roskam, I. (2020). Parental burnout: Moving the focus from children to parents. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 2020(174), 7–13. https://doi.org/10.1002/cad.20376

Ong, M. Y., Eilander, J., Saw, S. M., Xie, Y., Meaney, M. J., & Broekman, B. F. P. (2018). The influence of perceived parenting styles on socio-emotional development from pre-puberty into puberty. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 27(1), 37–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-017-1016-9

Peng, Y., Yang, X., & Wang, Z. (2021). Parental marital conflict and growth in adolescents’ externalizing problems: The role of respiratory sinus arrhythmia. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 43(3), 518–531. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-020-09866-9

Petersen, I. T., Bates, J. E., Dodge, K. A., Lansford, J. E., & Pettit, G. S. (2015). Describing and predicting developmental profiles of externalizing problems from childhood to adulthood. Development and Psychopathology, 27(3), 791–818. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579414000789

Philbrook, L. E., Erath, S. A., Hinnant, J. B., & El-Sheikh, M. (2018). Marital conflict and trajectories of adolescent adjustment: The role of autonomic nervous system coordination. Developmental Psychology, 54(9), 1687–1696. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000501

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 885(879), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63, 539–569. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452

Preacher, K. J., Rucker, D. D., & Hayes, A. F. (2007). Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 42, 185–227. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273170701341316

Ren, W. (1995). A study on the relationship between parental pressure, response strategy and satisfaction of parent-child relationship in young children [Unpublished master’s thesis]. National Taiwan Normal University.

Roeser, R. W., Eccles, J. S., & Strobel, K. R. (1998). Linking the study of schooling and mental health: Selected issues and empirical illustrations at…. Educational Psychologist, 33(4), 153–176. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep3304_2

Roskam, I., Aguiar, J., Akgun, E., Arikan, G., Artavia, M., Avalosse, H., Aunola, K., Bader, M., Bahati, C., & Barham, E. J. (2021). Parental burnout around the globe: A 42-country study. Affective Science, 2(1), 58–79. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42761-020-00028-4

Roskam, I., Brianda, M. E., & Mikolajczak, M. (2018). A step forward in the conceptualization and measurement of parental burnout: The Parental Burnout Assessment (PBA). Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 758–769. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00758

Roskam, I., & Mikolajczak, M. (2021). The slippery slope of parental exhaustion: A process model of parental burnout. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 77, Article 101354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2021.101354

Roskam, I., Mikolajczak, M., & Raes, M.-E. (2017). Exhausted parents: Development and preliminary validation of the Parental Burnout Inventory. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, Article 163. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00163

Russ, E., Heim, A., & Westen, D. (2003). Parental bonding and personality pathology assessed by clinician report. Journal of Personality Disorders, 17(6), 522–536. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi.17.6.522.25351

Sajid, B., & Shah, S. N. (2021). Perceived parental rejection and psychological maladjustment among adolescents of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Ilkogretim Online, 20(4), 1311–1318. https://doi.org/10.17051/ilkonline.2021.04.148

Shen, Z., Huang, L., Ye, M., & Lian, R. (2021). The effect of parental psychological control on adolescent problem behavior: The mediating role of parent-child relationship. Journal of Guizhou Normal University, 37(12), 78–84. (In Chinese).

Silinskas, G., Kiuru, N., Aunola, K., Metsäpelto, R.-L., Lerkkanen, M.-K., & Nurmi, J.-E. (2020). Maternal affection moderates the associations between parenting stress and early adolescents’ externalizing and internalizing behavior. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 40(2), 221–248. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431619833490

Skinner, A. T., Gurdal, S., Chang, L., Oburu, P., & Tapanya, S. (2022). Dyadic coping, parental warmth, and adolescent externalizing behavior in four countries. Journal of Family Issues, 43(1), 237–258. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X21993851

Smyth, N., Thorn, L., Oskis, A., Hucklebridge, F., Evans, P., & Clow, A. (2015). Anxious attachment style predicts an enhanced cortisol response to group psychosocial stress. Stress, 18(2), 143–148. https://doi.org/10.3109/10253890.2015.1021676

Sorkkila, M., & Aunola, K. (2020). Risk factors for parental burnout among Finnish parents: The role of socially prescribed perfectionism. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 29(3), 648–659. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01607-1

Szczygieł, D., Sekulowicz, M., Kwiatkowski, P., Roskam, I., & Mikolajczak, M. (2020). Validation of the Polish version of the Parental Burnout Assessment (PBA). New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 2020(174), 137–158. https://doi.org/10.1002/cad.20385

Tirfeneh, E., & Srah, M. (2019). Prevalence of depression and its association with parental neglect among adolescents at governmental high schools of Aksum town, Tigray, Ethiopia, 2019: A cross-sectional study. Depression Research and Treatment, 2020, Article 6841390. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.2.17823/v1

Wang, J., Zhang, Y., & Liang, Y. (2005). Analysis of Achenbach Adolescent Self-Assessment Scale among Middle School Students in Beijing. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, (02), 131–133+152. (In Chinese).

Wang, W., Wang, S., Cheng, H. W. Y., & Li, Y. (2021a). The mediating role of paternal parenting burnout between parenting stress and adolescent mental health. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 29(04), 858–861. https://doi.org/10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2021.04.040 (In Chinese).

Wang, W., Wang, S., Cheng, H. W. Y., & Li, Y. (2021b). Revision of the simplified Parental Burnout Scale Chinese version. Chinese Journal of Mental Health, 35(11), 941–946. (In Chinese).

Willems, Y. E., Li, J.-B., Hendriks, A. M., Bartels, M., & Finkenauer, C. (2018). The relationship between family violence and self-control in adolescence: A multi-level meta-analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(11), Article 2468. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15112468

Xia, Y., Li, S. D., & Liu, T.-H. (2018). The interrelationship between family violence, adolescent violence, and adolescent violent victimization: An application and extension of the cultural spillover theory in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(2), Article 371. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15020371

Xie, M., Fan, L., Wang, W., & Yongxin, Li. (2021). The mediating role of parenting burnout between fatherly psychological control and aggressive behavior and depression in children. Journal of Henan University (Medical Scienc), 40(05), 367–371. (In Chinese).

Xuan, X., Chen, F., Yuan, C., Zhang, X., Luo, Y., Xue, Y., & Wang, Y. (2018). The relationship between parental conflict and preschool children’s behavior problems: A moderated mediation model of parenting stress and child emotionality. Children and Youth Services Review, 95, 209–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.10.021

Yu, G. (2021). Parent burnout” in family education: A mental health perspective. Educational Research, Tsinghua University, 42(06), 21–28. https://doi.org/10.14138/j.1001-4519.2021.06.002108 (In Chinese).

Zhang, J., Zou, Y., Sheng, W., & Zhang, C. (2019). Parental parenting burnout: A new perspective on family parenting research. Special Education in China, 07, 91–96. (In Chinese).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Yifan Ping, Wei Wang, Yimin LI and Yongxin Li. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Yifan Ping and Wei Wang, all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Institute of Psychology and Behavior, Henan University. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Parenting stress

1. I often have the feeling that I cannot handle things very well | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

2. I find myself giving up more of my life to meet my children's needs than I ever expected | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

3. I feel trapped by my responsibilities as a parent | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

4. Since having this child I have been unable to do new and different things | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

5. Since having a child I feel that I am almost never able to do things that I like to do | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

6. I am unhappy with the last purchase of clothing I made for myself | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

7. There are quite a few things that bother me about my life | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

8. Having a child has caused more problems than I expected in my relationship with my spouse(male/female friend). | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

9. I feel alone and without friends | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

10. When I go to a party I usually expect not to enjoy myself | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

11. I am not as interested in people as I used to be | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

12. I don't enjoy things as I used to | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

13. My child rarely does things for me that make me feel good | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

14. Most times I feel that my child does not like me and does not want to be close to me | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

15. My child smiles at me much less than I expected | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

16. When I do things for my child I get the feeling that my efforts are not appreciated very much | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

17. When playing, my child doesn't often giggle or laugh | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

18. My child doesn't seem to learn as quickly as most children | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

19. My child doesn't seem to smile as much as most children | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

20. My child is not able to do as much as I expected | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

21. It takes a long time and it is very hard for my child to get used to new things | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

22. I expected to have closer and warmer feelings for my child than I do and this bothers me | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

23. Sometimes my child does things that bother me just to be mean | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

24. My child seems to cry or fuss more often than most children | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

25. My child generally wakes up in a bad mood | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

26. I feel that my child is very moody and easily upset | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

27. My child does a few things which bother me a great deal | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

28. My child reacts very strongly when something happens that my child doesn't like | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

29. My child gets upset easily over the smallest thing | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

30. My child's sleeping or eating schedule was much harder to establish than I expected | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

31. There are some things my child does that really bother me a lot | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

32. My child turned out to be more of a problem than I had expected | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

33. My child makes more demands on me than most children | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

34. I feel that I am: | 1. not very good at being a parent | 2. a person who has some trouble being a parent | 3. an average parent | 4. a better than average parent | 5. a very good parent | |||||

35. I have found that getting my child to do something or stop doing something is: | 1. much harder than I expected | 2. somewhat harder than I expected | 3. about as hard as I expected | 4. somewhat easier than I expected | 5. much easier than I expected | |||||

36. Think carefully and count the number of things which your child does that bother you. For example, dawdles, refuses to listen, overactive, cries, interrupts, fights, whines, etc. Please circle the number which includes the number of things you counted | 1. 10 + | 2. 8–9 | 3. 6–7 | 4. 4–5 | 5. 1–3 | |||||

Parenting styles scale (Time 1)

1 In order to avoid negative effects, I don't think children can choose books to read by themselves (为了避免不良影响, 我认为不能让孩子自己选择书本来读) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

2 I think it is important to let children have an opportunity to express their own views (我认为应该让孩子有机会表达他们的观点) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

3 I often blame children as “stupid” “worthless” (我经常骂孩子 “笨蛋”、 “没出息”) … | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

Parental burnout

1. I can't stand my role as father/mother anymore | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

2. I feel like I can’t take any more as a parent | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

3. When I get up in the morning and have to face another day with my child, I feel exhausted before I’ve even started | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

4. I feel completely run down by my role as a parent | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

5. I don't think I'm the good father/mother that I used to be to my child(ren) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

6. I tell myself that I’m no longer the parent I used to be | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

7. I'm no longer able to show my child(ren) how much I love them | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

Problem behavior

1. I have an allerge (describe) | 0 | 1 | 2 |

2. I argue a lot | 0 | 1 | 2 |

3. I act like the opposite sex | 0 | 1 | 2 |

4. I cry a lot | 0 | 1 | 2 |

5. I am mean to others | 0 | 1 | 2 |

6. I try to get a lot of attention | 0 | 1 | 2 |

7. I destroy my own things | 0 | 1 | 2 |

8. I destroy things belonging to others | 0 | 1 | 2 |

9. I disobey my parents | 0 | 1 | 2 |

10. I disobey at school | 0 | 1 | 2 |

11. I don’t feel guilty after doing something I shouldn’t | 0 | 1 | 2 |

12. I am willing to help others when they need help | 0 | 1 | 2 |

13. I am afraid of certain animals situations or places, other than school(describe): | 0 | 1 | 2 |

14. I am afraid of going to school | 0 | 1 | 2 |

15. I am afraid I might think or do something bad | 0 | 1 | 2 |

16. I feel that I have to be perfect | 0 | 1 | 2 |

17. I feel that no one loves me | 0 | 1 | 2 |

18. I feel worthless or inferior | 0 | 1 | 2 |

19. I get in many fights | 0 | 1 | 2 |

20. I hang around with kids who get in trouble | 0 | 1 | 2 |

21. I would rather be alone than with others | 0 | 1 | 2 |

22. I lie or cheat | 0 | 1 | 2 |

23. I am nervous or tense | 0 | 1 | 2 |

24. I am too fearful or anxious | 0 | 1 | 2 |

25. I feel too guilty | 0 | 1 | 2 |

26. I physically attack people | 0 | 1 | 2 |

27. I would rather be with older kids than with kids my own | 0 | 1 | 2 |

28. I refuse to talk | 0 | 1 | 2 |

29. I run away from home | 0 | 1 | 2 |

30. I scream a lot | 0 | 1 | 2 |

31. I am secretive or keep things to myself | 0 | 1 | 2 |

32. I am self-conscious or easily embarrassed | 0 | 1 | 2 |

33. I set fires | 0 | 1 | 2 |

34. I am shy | 0 | 1 | 2 |

35. I steal at home | 0 | 1 | 2 |

36. I steal from places other than home | 0 | 1 | 2 |

37. I am stubborn | 0 | 1 | 2 |

38. My moods or feelings change suddenly | 0 | 1 | 2 |

39. I am suspicious | 0 | 1 | 2 |

40. I swear or use dirty language | 0 | 1 | 2 |

41. I think about kill myself | 0 | 1 | 2 |

42. I tease others a lot | 0 | 1 | 2 |

43. I have a hot temper | 0 | 1 | 2 |

44. I think about sex too much | 0 | 1 | 2 |

45. I threaten to hurt people | 0 | 1 | 2 |

46. I am too concerned about being neat or clear | 0 | 1 | 2 |

47. I cut classes or skip school | 0 | 1 | 2 |

48. I cut classes or skip school | 0 | 1 | 2 |

49. I am unhappy, sad, or depressed | 0 | 1 | 2 |

50. I am louder than other kids | 0 | 1 | 2 |

51. I use alcohol or drugs for nonmedical (describe): | 0 | 1 | 2 |

52. I keep from getting involved with others | 0 | 1 | 2 |

53. I worry a lot | 0 | 1 | 2 |

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ping, Y., Wang, W., Li, Y. et al. Fathers’ parenting stress, parenting styles and children’s problem behavior: the mediating role of parental burnout. Curr Psychol 42, 25683–25695 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03667-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03667-x