Abstract

Counter-intuitively, sociodemographic characteristics account for a small proportion of explained variance in parental burnout. The present study conducted during the Covid-19 pandemic asks whether (i) sociodemographic characteristics are more predictive of parental burnout than usual in a situation of lockdown, (ii) situational factors, that is, the specific restrictive living conditions inherent in the context of lockdown, predict parental burnout better than sociodemographic characteristics do, and (iii) the impact of both sociodemographic and situational factors is moderated or mediated by the parents’ subjective perception of the impact that the health crisis has had on their parenting circumstances. Results show that, within the context of lockdown, both sociodemographic and situational factors explain a negligible proportion of variance in parental burnout. By contrast, parents’ cognitive appraisals of their parenthood within the context of the health crisis were found to play both a crucial mediating and moderating role in the prediction of parental burnout.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Parental burnout occurs in response to chronic and overwhelming parenting stress (Mikolajczak et al., 2019; Mikolajczak, Brianda, et al., 2018; Mikolajczak, Raes, et al., 2018; Mikolajczak & Roskam, 2018; Mikolajczak et al., 2020). It is defined by four core symptoms: (i) intense exhaustion resulting from one’s parental role, (ii) loss of fulfillment in one’s parental role, (iii) emotional distancing from one’s children, and (iv) a striking perceived contrast between previous and current parental self (Mikolajczak et al., 2019; Roskam et al., 2021). Importantly, parental burnout is distinct from job burnout and depression: these three conditions show moderate correlations (Mikolajczak et al., 2019), factorial distinctiveness, and separable consequences (Mikolajczak et al. 2020).

Parental burnout is quite common: point prevalence estimates range from 5 to 9% in Western countries (Roskam et al., 2021). What is more, parental burnout is significant because its consequences can be dramatic both for the parent and the child, including suicidal ideation and poor health in the parent (Brianda et al., 2020a, b), and long-term damage to psychological and physical development in the child (Hansotte et al., 2020; Mikolajczak et al., 2019).

According to the Balance between Risks and Resources (BR2) model (Mikolajczak & Roskam, 2018), parental burnout results from a chronic imbalance between risk and protective factors. One may intuitively think that objective sociodemographic characteristics (such as being a single parent, having a low income, or having a child with specific needs) might constitute major risk factors for parental burnout. Yet, counter-intuitively, objective sociodemographic factors only explain a small proportion of variance in parental burnout. This has been consistently demonstrated across independent studies which rely on large samples of participants originating from different cultures around the globe (Arikan et al., 2020; Gannagé et al., 2020; Matias et al., 2020; Mikolajczak, Brianda, et al., 2018; Mikolajczak, Raes, et al., 2018; Mousavi et al., 2020; Roskam et al., 2021; Stănculescu et al., 2020; Szczygieł et al., 2020).

But, what if sociodemographic factors– hitherto found to be hardly significant in predicting parental burnout– would predict parental burnout better in the context of lockdown due to the Covid-19 pandemic? When the world went into lockdown to protect its people’s health, governments all around the world imposed stay-at-home orders shutting schools, banning all non-essential travel, businesses and gatherings, and making telework mandatory. Hence, the workforce whose job could not apply to telework was put on temporary unemployment due to force majeure. Numerous families had to struggle hard to go through the crisis and re-balance their everyday life. All families’ daily hassles considerably worsened since parents ended up cooped up with partner and children while teleworking (sometimes with an extra workload), had to improvise as teachers and some of them even experienced financial distress due to temporary unemployment. To make matters worse, the less fortunate could not benefit from outdoor spaces nearby their house where the family could, at least for a little while, escape from the oppressive feeling of being closed in.

If sociodemographic factors have consistently failed to predict parental burnout outside the context of the current health crisis, it may be explained by the fact that, before the outbreak of the pandemic, all parents (at risk and non-at-risk groups) usually managed to alleviate the impact of sociodemographic factors by relying on the valuable support of friends, grand-parents or relatives who helped with young and little autonomous children or went for a walk with the children to compensate for a small living area, for instance. If this is the case, sociodemographic factors could predict parental burnout better during the lockdown, since parents are now deprived of the external resources which they ordinarily leaned on to alleviate their parenting burden. The health crisis could thus be viewed as a naturally induced psychological stress test that may allow to better study the predictive weight of sociodemographic stressors in the absence of compensatory resources. Hence, the predictive power of socio-demographics during the lockdown might be further increased by adding into the model the situational factors that are specifically relevant in the context of lockdown.

Depending on the parent’s sociodemographic situation, that is, at risk for parental burnout (single-parent, economically distressed parent, parent living with a child with special needs, etc.) versus not at risk, parents might develop a specific subjective perception of the impact that the health crisis has had on their parenthood. Hence, if sociodemographic and/or situational factors are predictive of parental burnout in the context of the current health crisis, we could further assume a mediating effect of cognitive appraisals (i.e., the individual’s subjective perception of the situation) (Arnold, 1960; Lazarus, 1991; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984) on the association between these factors and parental burnout. In that regard, we could hypothesize that the parents who are more at risk for parental burnout would be steered towards negatively appraising the effect of the health crisis on their parenting conditions, thereby increasing their parental burnout symptoms. By contrast, the parents who are not at risk for parental burnout would tend to appraise the effect of the coronavirus global pandemic on their parenting conditions as more positive, thereby lessening their parental burnout level.

To illustrate the mediating effect of the cognitive appraisals, think of the parents whose child needs specific medical or psychological care. Their difficult daily routine coupled with the harsh living conditions (caused by governmental restrictions due to the Covid-19 pandemic), might cause them to develop negative appraisals of the impact that the health crisis has had on their parenthood, thereby exposing them more importantly to parental burnout. This mediating effect of appraisals may be particularly salient during the pandemic. Indeed, before the outbreak of the pandemic, many parents (at-risk and non-at-risk groups) usually managed to alleviate the impact of sociodemographic factors by relying on various resources. These resources may have fostered more positive appraisals of their situation, thereby masking the link between sociodemographic factors and parental burnout. Hence, in the context of the Covid-19 global pandemic, sociodemographic factors may predict parental burnout better than usual because the parents are now deprived of the external resources. This sudden deprivation might thus steer these parents towards negatively appraising their parenthood, and therefore put them at higher risk for parental burnout.

While cognitive appraisals could act as mediators of the relationship between sociodemographic and/or situational factors and parental burnout, they could also act as moderators of the relationship. Indeed, appraisals (positive or negative) are not only determined by circumstances. They are also determined by stable individual factors such as personality and emotional competences. Some people have a natural tendency to appraise events positively (e.g., people with high emotional competence; Mikolajczak & Luminet, 2008), while others have a natural inclination to appraise them negatively (e.g., people high on neuroticism; Schneider, 2004; Tong, 2010). Based on this, we could posit the existence of a moderating effect of the parents’ cognitive appraisals in the relationship between sociodemographic characteristics and parental burnout. In that regard, we could hypothesize that sociodemographic and/or situational factors may increase parental burnout symptoms (only) when parents develop negative appraisals of the health crisis on their parenting circumstances. Conversely, the potentially deleterious effect of sociodemographic and/or situational factors may be alleviated when parents make positive appraisals of their parenting conditions within the Covid-19 pandemic.

The aim of this study is fourfold. First, it aims at investigating whether in the current Covid-19 pandemic context, objective sociodemographic factors predict parental burnout better than in non-pandemic contexts. To achieve this first goal, we will use a second set of data for comparison purposes (see Participants section below). Second, it sets out to investigate whether objective situational factors related to the Covid-19 context (e.g., teleworking, homeschooling, being locked down with partner, etc.) are predictive of parental burnout. Third, it aims to test whether the impact of sociodemographic as well as situational factors on parental burnout may be mediated by the parent’s cognitive appraisals. Finally, this research investigates whether the parent’s cognitive appraisals might moderate the impact of the relationship between socio-demographics as well as situational factors and parental burnout.

We hypothesize that:

-

1.

in the current context of the Covid-19 global pandemic, sociodemographic factors are more predictive of parental burnout than usual, that is in non-pandemic contexts;

-

2.

the situational factors related to the specific restrictive living conditions that ensue from governmental decisions to fight the Covid-19 global pandemic (i.e., teleworking, teaching one’s children, being locked down with one’s partner, being subject to a change in financial situation, having the possibility– or not to enjoy large open spaces nearby the house) account for parental burnout symptoms over and above sociodemographic factors;

-

3.

the positive and negative appraisals that the parents have of the impact that the Covid-19 pandemic has had on their parenthood mediate the relationship between sociodemographic as well as situational factors and parental burnout;

-

4.

the positive and negative appraisals that the parents have of the impact that the Covid-19 pandemic has had on their parenthood will also moderate the relationship between sociodemographic as well as situational factors and parental burnout.

Material and Methods

Preregistration

We preregistered the analysis plan, methodology and a description of the dataset. De-identified data are available via the Open Science Framework and can be accessed at https://osf.io/x7vhc/?view_only=59fe6935f02c4924a09df524c0bf9af7. The only deviations from this analysis plan were as follows: we opted to use the sociodemographic variable that informs us about the exact number of children living under the same roof as the participant instead of the variable that informs us about the number of biological and/or adopted children the participant has; we created a new variable (i.e., number of children aged under four years old or under) in order to allow the comparison of bivariate correlations across two different sets of data (see Participants section below); and we computed a new continuous variable summing the number of physiological and/or psychological problems the participant has ever encountered.

Participants

A convenience sample of 1,212 parents (1,097 mothers and 115 fathers) living in Belgium took part in the survey. Data collection took place from March to May 2020, that is, during the strict lockdown in Belgium due to the Covid-19 health crisis. Note that during this strict lockdown, the Belgian government severely curtailed public life by giving stay-at-home orders. Companies had to organize teleworking wherever it was possible, schools and non-essential shops had to close (except for (pet) food shops and pharmacies whose access was limited to one person per ten square meters for a maximum duration of thirty minutes per customer). Belgian police were requested to strictly enforce the confinement and to impose heavy fines in case of non-compliance with the established rules.

The study was presented as part of an international study designed to understand better the factors which lead to fulfillment in one’s parenthood and those which lead to exhaustion while parenting. We concealed the specific objectives of the study in order to avoid (self-) selection bias. Participants were recruited through social networks, e-mails and word-of-mouth. The sociodemographic features of the participants are presented in Table 1. Respondents were invited to complete an online survey on Qualtrics after signing an online informed consent form.

The inclusion criteria were (i) being a parent having at least one child still living under the same roof, (ii) living in a country in a situation of lockdown due to the Covid-19 health crisis, (iii) being an over 18 years old parent, and (iv) being fluent in French. Almost all participants met these inclusion criteria except for 0.36% of them (N = 6) who reported living in a country that was not in a situation of lockdown. These subjects were removed from the dataset.

To ensure that the participants responded seriously, three attentional check questions were randomly added in the survey. 7.07% of the subjects (N = 119) failed for at least one of the three attentional check items and were thus removed from our analyses.

Although the “answer required” option in Qualtrics was set, some participants started the survey completion but terminated before reaching the end of the survey. We observed an attrition rate of 19.2% (N = 324). Binary logistic regression analyses were carried out on each independent variable separately to avoid the cumulative effect of missing data on the variables. These analyses revealed statistically significant differences among the subjects who dropped out: younger parents (B = -.02, p < 0.05), partnered parents (B = -.23, p < 0.001), the fact of being a parent with at least one physiological or physical problem (B = 0.57, p < 0.001), the fact of living in a spacious house (B = 0.004, p < 0.001), and the fact of being locked down with one’s partner (B = .57, p < 0.05). Although we cannot assume that data are missing completely at random (MCAR), the subjects displaying missing values on the variables of interest in this study were listwise deleted (see Limitations section).

We finally examined implausible and/or contradictory values. For example, the level of education [i.e., number of successfully completed school years from the age of 6] could not exceed the participant’s age minus 6. One participant was found displaying implausible and contradictory values and was thus removed from the analyses.

To test Hypothesis 1 exclusively, we drew upon a previously obtained second set of data composed of 1,689 parents (1,457 mothers and 232 fathers) living in Belgium before the lockdown period (viz., from January 2018 to November 2019) (Roskam et al., 2021). Comparison was made possible since the two datasets were collected according to the same procedure in the framework of the International Investigation of Parental Burnout (IIPB) Consortium (see Procedure section below) among Belgian parents. In that regard, these two sets share identical inclusion criteria, recruitment methods, and use of Qualtrics. A comprehensive description of this second set of data as well as the database itself are available on OSF at: https://osf.io/94w7u/?view_only=a6cf12803887476cb5e7f17cfb8b5ca2

Procedure

In March 2020, on the initiative of Prof. van Bakel from the University of Tilburg, each member of the International Investigation of Parental Burnout (IIPB) Consortium (Roskam et al., 2021) was invited to collect data to examine the prevalence of parental burnout during the Covid-19 global pandemic. The goal of this international data collection (whose complete protocol is presented in the current article’s online supplementary material) was to compare the prevalence of parental burnout in usual living conditions (i.e., from January 2018 to November 2019, see Roskam et al., 2021) with the prevalence of parental burnout within the context of the Covid-19 health crisis in 2020 (van Bakel et al., in preparation). In the scope of this international study led by van Bakel, a wide range of variables were probed, of which only some are relevant to the current study (see Measures section below for a comprehensive overview of the variables of interest in this research).

The present study was approved by the Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Socio-demographic Questions

The survey measured the following socio-demographic features of the participants: gender, age, educational attainment, type of the family (two-parent, single parent, homo-parental, other), number of children living in the household, number of children aged from 0 to 4, number of children aged from 5 to 9, number of children aged from 10 to 14, number of children aged from 15 to 18, number of children aged over 19, number of children displaying physiological or psychological problem, number of physiological or psychological problem of the parent, and living area of the house.

Situational Factors Related to the Covid-19 Lockdown Context

We included the following measures to assess the impact of the lockdown due to the Covid-19 global pandemic: is the parent working from home (teleworking), is the parent teaching his or her children (homeschooling), is the parent locked down with his or her partner, has the parent experienced any change in his or her financial situation, and are there any outdoor spaces nearby the house?

Cognitive Appraisals Questions

Two items designed to probe the participants’ cognitive appraisals of the impact that the Covid-19 health crisis has had on their parenthood were assessed: positive appraisal [When you think of the coronavirus health crisis, to what extent do you think it has had a positive impact on your parenthood and on your attitudes towards your children (e.g., experiencing more quality time, having closer contact)], negative appraisal [When you think of the coronavirus health crisis, to what extent do you think it has had a negative impact on your parenthood and on your attitudes towards your children (e.g., experiencing less quality time, having more conflicts)].

A comprehensive description of the sociodemographic, situational and cognitive appraisals measures is available in the current article’s online supplementary material.

Parental Burnout

We measured parental burnout with the Parental Burnout Assessment (PBA (Roskam et al., 2018)), a 23-item self-report questionnaire assessing the four core symptoms of parental burnout, namely, Emotional exhaustion (9 items) (e.g., I’m so tired out by my role as a parent that sleeping doesn’t seem like enough), Emotional distancing from one’s children (3 items) (e.g., I do what I’m supposed to do for my child(ren) but nothing more), Loss of pleasure in one’s parental role (5 items) (e.g., I don’t enjoy being with my child(ren)), and Contrast with previous parental self (6 items) (e.g., I am ashamed of the parent I have become). The items of the PBA use a Likert scale that ranges from 0 to 6 (viz., never, a few times a year, once a month or less, a few times a month, once a week, a few times a week, every day). Summing every item scores of the PBA enables to compute the individual’s parental burnout global score, which theoretically ranges from 0 to 138. The higher the score, the higher the level of parental burnout. Since we have no specific hypothesis regarding the sub-scales of the PBA, we used the global score exclusively. Its internal consistency was excellent (Cronbach’s α = 0.98).

Statistical Analyses

Preliminary Analyses

After a few preliminary checks on the dataset (e.g., attentional checks, implausible answers, etc. (see Participants section)), we performed additional analyses regarding normality, potential collinearity issues, statistical power and bivariate correlation of the two cognitive appraisals items. For a detailed report of these analyses, please consult the online supplementary material of the current paper.

Main Analyses

All analyses were performed using SPSS Version 27 (IBM Corp., 2020) except for the analyses of mediation and moderation related to Hypotheses 3 and 4 respectively, for which we used Stata Version 16 (Stata Corp. LLC, 2019).

In order to test Hypothesis 1 (i.e., sociodemographic factors will predict parental burnout better in a context of lockdown than usual), we compared the bivariate correlations between the sociodemographic variables and the parental burnout scores obtained in Belgium before the health crisis (viz., from January 2018 to November 2019) with the correlations obtained during the strict lockdown in Belgium (viz., from March to May 2020). To allow the comparison, we performed our analyses only on the sociodemographic variables that were common in the two datasets. We carried out z-tests relying on Eid et al. (2011) calculations to compare the bivariate correlations obtained from the two sets of data. First, we examined and compared the Spearman bivariate correlations for the following sociodemographic variables: gender, age, educational attainment, number of children living under the same roof, number of children aged four years old and under [none, at least one]). Second, regarding the categorical variable family type [two parents, single parent, other (i.e., step-family, homo-parental, multigenerational, polygamous, other)], we ran ANOVAs with post-hoc tests across the two datasets to discover what categories of the family type predictor might differ from the others. The effect sizes were appreciated relying on the eta squares thresholds established by Cohen (1988) (0.01 = small, 0.06 = medium, 0.14 = large).

In order to test Hypothesis 2 (i.e., situational factors related to the Covid-19 global pandemic will predict parental burnout over and above sociodemographic factors), we ran a hierarchical linear regression. In step one, we entered the sociodemographic variables known to be predictive of parental burnout: gender, age, educational attainment, family type [two parents, single parent, other], number of children living in the household, number of children aged from 0 to 4 [none, one, two or more], number of children aged from 5 to 9 [none, one, two or more], number of children aged from 10 to 14 [none, one, two or more], number of children aged from 15 to 18 [none, one, two or more], number of children aged 19 and over [none, one, two or more], number of children displaying a medical, physical, emotional, cognitive or behavioral problem [none, at least one], number of physiological or psychological problem of the parent and finally, house living surface. In step two, while controlling for the above-mentioned sociodemographic predictors, we entered the situational variables inherent in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic, that is, teleworking, teaching one’s children, being locked down with– or without one’s partner, having the possibility– or not to enjoy large open spaces nearby the house, being subject– or not to a change in financial situation. Regarding the teleworking categorical variable [no work because of Covid-19, reduced workload, same workload, extra workload, no paid activity at the moment, continue doing same job], we ran ANOVAs to find out which of its categories were significant.

To test Hypothesis 3 (i.e., parents’ cognitive appraisals will mediate the relationship between sociodemographic as well as situational factors and parental burnout), we ran a mediation model that included (i) the eight sociodemographic and situational factors that were statistically significant from previous analyses (see Statistical Analyses section above related to Hypothesis 2), namely, gender, having children aged four years old or under, having at least one child displaying a medical, physical, emotional, cognitive or behavioral problem, being a parent displaying at least one physiological or psychological problem, having no professional activity, being teleworking with extra workload, not being locked down with one’s partner, not being able to benefit from open spaces nearby the house, (ii) two mediators (i.e., positive appraisal and negative appraisal) and (iii) the parental burnout dependent variable. The mediation model controlled for the covariations between the eight entered predictors and for the covariation between the two mediators.

Finally, in order to test Hypothesis 4 (i.e., parents’ cognitive appraisals will moderate the relationship between sociodemographic as well as situational factors and parental burnout), we performed a moderation analysis. We mean-centered the variables before introducing them into the model to reduce multicollinearity between the main effects and the interaction terms (Cohen et al., 2013). The moderation model included (i) the eight sociodemographic and situational factors used in the above mediation model (i.e., gender, having children aged four years old or under, having at least one child displaying a medical, physical, emotional, cognitive or behavioral problem, being a parent displaying at least one physiological or psychological problem, having no professional activity, being teleworking with extra workload, not being locked down with one’s partner, not being able to benefit from open spaces nearby the house), (ii) two moderators (i.e., positive appraisal and negative appraisal) and (iii) the parental burnout dependent variable. The moderation model controlled for the covariations between the eight entered predictors and for the covariation between the two moderators.

A simplified version of the two conceptual models of mediation and moderation respectively is outlined in Fig. 1.

Results

-

Hypothesis 1: Sociodemographic factors will predict parental burnout better in a context of lockdown than usual.

Although modest in size (∣ < 0.30∣), the correlations globally revealed slight changes between the two periods (before and during the lockdown due to the Covid-19 pandemic). The results related to the gender and the age of the parent as well as the fact of having at least one child aged four years old or under, revealed no change in the direction of the association but change in the force of this association. Hence, before the lockdown, mothers were found to display greater parental burnout scores than fathers, but this difference was significantly reduced during the lockdown, z = -2.90, p < 0.01 (rs before lockdown = 0.20; rs during lockdown = 0.09). Regarding the age of the parent, before the lockdown, the older the parents were, the lesser they experienced parental burnout, and this was significantly more salient in the context of lockdown where the correlation almost tripled, z = -2.77, p < 0.01 (rs before lockdown = -.06; rs during lockdown = -.16). As for the parents who had at least one child aged four years old or under, they displayed even greater parental burnout symptoms during the lockdown, z = 2.16, p < 0.05 (rs before lockdown = 0.09; rs during lockdown = 0.17). The fourth correlation related to the educational attainment of the parent showed a change both in the direction and in the force of the association since, before the lockdown period, the more educated parents seemed less at risk for parental burnout. The opposite was true during the lockdown, where the more educated parents were significantly more at risk, z = 1.99, p < 0.01 (rs before lockdown =-.05; rs during lockdown = .29). Finally, only the z-test related to the number of children living under the same roof as the parent was not statistically significant, z = -1.24, p > 0.05 (rs before lockdown = 0.13; rs during lockdown = .09), meaning that there was no change neither in the direction nor in the force of association between this sociodemographic factor and parental burnout before and during the lockdown due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

The ANOVAs we further ran in order to compare the situation between the two periods regarding the categorical family type variable indicated that during the lockdown, being a partnered parent (M = 32.70, SD = 31.43), a single parent (M = 38.71, SD = 34.94), or a parent in any other type of family (M = 31.55, SD = 31.31) did not account for any difference in parental burnout scores, F(2,1193) = 2.46, p > 0.05, \(\eta\) 2 = 0.004. By contrast, although we obtained a very small effect size, before the lockdown, we observed a difference between partnered parents (M = 35.53, SD = 29.78), and single parents (M = 42.11, SD = 35.73), the latter displaying more parental burnout symptoms. No difference appeared between other types of family (M = 41.98, SD = 35.53) and partnered or single parents, F(2,1649) = 5.65, p < 0.01, \(\eta\) 2 = 0.007.

Hence, although modest in size, the slight changes in the association between some sociodemographic factors and parental burnout (revealed by the z-tests), support Hypothesis 1 which assumed that socio-demographics would predict parental burnout better in a context of lockdown than usual.

-

Hypothesis 2: Situational factors related to the Covid-19 global pandemic will predict parental burnout over and above sociodemographic factors.

In step one, the results of the hierarchical regression (see Table 2) showed that during the lockdown, sociodemographic characteristics continued to explain very little variance in parental burnout, R2 = 0.14, F(13,1182) = 16.54, p < 0.001.

In step two, while controlling for sociodemographic factors, we added situational factors (i.e., the specific living conditions associated with the lockdown). Seven sociodemographic and situational predictors turned out statistically significant, with risk for parental burnout associated with. Regarding the sociodemographic predictors, we observed: female gender (B = 8.24, p < 0.01), having at least one child aged four years old or under (B = 9.25, p < 0.01), having at least one child displaying a medical, physical, emotional, cognitive or behavioral problem (B = 11,46, p < 0.001), and finally, the parents themselves who display a physiological or psychological problem (B = 7.30, p < 0.001). Among the statistically significant situational predictors related to the covid-19 specific living conditions we observed: working from home (B = 1.21, p < 0.05) (for which the results of the ANOVA indicated that the parents who are not working (M = 46.25, SD = 36.11) and those who are teleworking with an extra workload (M = 40.13, SD = 33.07) are the most at risk for parental burnout, F(5,1206) = 7,67, p < 0.001, \(\eta\)2= 0.03), being a parent locked down without one’s partner (B = 3.08, p < 0.05) and finally, not being able to rely on large outdoor spaces where one’s children can go and let off steam (B = 6.84, p < 0.05). While controlling for the sociodemographic features, situational factors were found to explain hardly any more variance than socio-demographics, R2 = 0.15, ∆R2 = 0.01., F(18,1177) = 13.04, p < 0.001.

Consequently, despite a very trivial increment in R-squared (1%), Hypothesis 2, that assumed that situational factors related to the Covid-19 pandemic would predict parental burnout over and above socio-demographics, can be validated.

-

Hypothesis 3: Parents’ cognitive appraisals (positive and negative) will mediate the relationship between sociodemographic as well as situational factors and parental burnout.

We ran a model that tested the mediating effect of positive and negative appraisals respectively on the relationship between each of the eight sociodemographic and situational factors that turned out statistically significant from Hypothesis 2 and parental burnout. For the convenience of the reader, only the significant mediating effects that are relevant to Hypothesis 3 are outlined in Fig. 2. The bivariate relations between the variables under consideration is presented in Table 3 and the results related to direct, indirect and total effects are presented in Table S2 of the current paper’s online supplementary material.

The mediation path model accounted for 45% of the explained variance in parental burnout. Three of the eight sociodemographic and situational predictors introduced in the mediation path model appeared to be mediated by the cognitive appraisals made by the parents about the impact that the coronavirus health crisis had had on their parenthood: gender (direct effect: β = 3.25, p > 0.05); indirect effect: β = 4.25, p < 0.05) with direct positive effect towards negative appraisals (β = .24, p < 0.01), which indicated that mothers were more prone to negative appraisals than fathers. Having at least one child with a medical, physical, emotional, cognitive or behavioral problem (direct effect: β = 5.33, p < 0.01); indirect effect: β = 6.98, p < 0.001), with a direct negative effect towards positive appraisals (β = -.26, p < 0.01) and a direct positive effect towards negative appraisals (β = .33, p < 0.001), meaning that the parents who have a child living with physical, behavioral or psychological issues tended to make less positive appraisals and more negative appraisals about their parenting circumstances when they thought of the impact that the health crisis had had on their parenthood. Working from home with extra workload (direct effect: β = -2.46, p > 0.05); indirect effect: β = -6.76, p < 0.01), with a direct positive effect towards positive appraisals (β = .34, p < 0.05) and a direct negative effect towards negative appraisals (β = -.30, p < 0.05) indicated that the parents whose workload had remained unchanged were steered towards making positive appraisals. By contrast, the parents who were teleworking with an additional workload were steered towards making negative appraisals about the impact that the coronavirus health crisis has had on their parenthood. In turn, positive and negative appraisals relate to parental burnout.

The results related to Hypothesis 3 (according to which parents’ cognitive appraisals would mediate the relationship between socio-demographics as well as situational factors and parental burnout) support the Hypothesis, in particular for socio-demographics.

-

Hypothesis 4: Parents’ cognitive appraisals (positive and negative) will moderate the relationship between sociodemographic as well as situational factors and parental burnout.

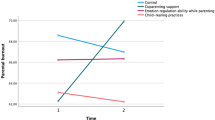

This last hypothesis was tested while running a model that examined the moderating effect of positive and negative appraisals respectively on the relationship between each of the same eight predictors used in the mediation analyses (see Hypothesis 3 section above) and parental burnout. For the convenience of the reader, only the significant interaction terms and the bivariate correlations of the variables introduced in the model are depicted in Fig. 3 and presented in Table 3 respectively. As for the results related to the ((non-significant) main effects and interaction terms, they are presented in Table S3 of the current article’s online supplementary material.

Significant interaction effects of positive and negative appraisal respectively in the relationships between gender and parental burnout (Interaction term 1), child aged four years old or under and parental burnout (Interaction term 2) and parent living with physical or psychological issues and parental burnout (Interaction term 3)

The moderation model accounted for 47% of the variance in which four statistically significant main effects were observed: having at least one child aged four years old or under, (β = .14, p < 0.001), having at least one child displaying a medical, physical, emotional, cognitive or behavioral problem (β = .07, p < 0.01), being a parent displaying a physiological or psychological problem (β = .09, p < 0.001), having no professional activity (β = .06, p < 0.05). We further observed three significant interaction terms. Thus, positive appraisal was a significant moderator of the relationship between gender (β = -.34, p < 0.05) and parental burnout. It was also a significant moderator of the relationship between the fact of having at least one child aged four years old or under (β = -.11, p < 0.01) and parental burnout. As for negative appraisal, it was found to moderate the relationship between the fact of being a parent displaying a physiological or psychological problem and parental burnout (β = .21, p < 0.05). The plotted interactions terms (see Fig. 3) indicated that at low levels of positive appraisal, mothers are more prone to parental burnout than fathers and that at high levels of positive appraisals, the opposite is true. Positive appraisals hence revealed themselves as a protective factor, especially for mothers. Having at least one child aged four years old or under does not represent a risk factor for parental burnout when coupled with high levels of positive appraisals, while it does, in case of low levels of positive appraisals. Finally, regarding the parents who live with a physiological or psychological problem, it appeared that high levels of negative appraisal significantly increased their risk for parental burnout.

Thereupon, Hypothesis 4 (according to which parents’ cognitive appraisals would moderate the relationship between socio-demographics as well as situational factors and parental burnout) is supported, in particular for socio-demographics.

Discussion

The results of the present study do not only corroborate the consistent conclusions drew from previous studies around the globe according to which objective sociodemographic characteristics account for a low amount of explained variance in parental burnout (Arikan et al., 2020; Gannagé et al., 2020; Matias et al., 2020; Mousavi et al., 2020; Roskam et al., 2021; Stănculescu et al., 2020; Szczygieł et al., 2020), but they also show that, within a context of lockdown caused by the coronavirus pandemic, these objective sociodemographic characteristics continue to have a little predictive power.

Although we had expected that the restrictive living conditions inherent in the context of the health crisis would have propelled parents in a downward spiral towards parental burnout, this was not the case. Yet, some slight changes were observed between the two periods. Special caution must nonetheless be taken while interpreting the results since the correlations are negligible and probably turned out statistically significant because of the large sample sizes.

During the lockdown, the difference in parental burnout levels was lessened between mothers and fathers (mothers usually scoring higher than fathers on the parental burnout scale). We hypothesize that staying enclosed at home lifted up the Western societies prescribes that pressurize mothers to be perfect (Christler, 2013, as cited in Meeussen & Van Laar, 2018). Another explanation for this phenomenon could be that, fathers, as of then cooped up in the house with partner and offspring, were more largely exposed to the daily hassle associated with parenting. Since the comparison was made between two independent samples, it makes it impossible to disentangle which explanation is best suited here. Also, being older as a parent seemed to decrease parental burnout during the lockdown, thereby suggesting that maturity and expertise in parenthood might be protective factors against parental burnout. The lockdown that isolated parents with young and little autonomous children found these parents even more exhausted than usual, probably due to the absence of practical (e.g., day care) and emotional external support to alleviate the very demanding job of caring for toddlers (Parkes et al., 2015). Surprisingly, the lockdown did not exacerbate the precarious situation of single parents.

Although counter-intuitive, situational factors (or the specific restrictive living conditions ensuing from governmental decisions to fight the Covid-19 pandemic) were found to account for a very low amount of explained variance in parental burnout. By all accounts, assuming the central role played by the cognitive appraisals made by the parents about their own parenting circumstances, is the key to understanding why statistical models that only include objective socio-demographics and/or situational predictors remain hardly predictive of parental burnout.

The positive and negative appraisals made by the parents about the impact that the health crisis has had on their parenthood, revealed themselves as potent underlying factors to explain an important proportion of variance in parental burnout. In the case of mediation, it appeared that the favorable or the deleterious sociodemographic environment of the parents steers them towards– respectively– positively or negatively appraising their parenting circumstances. Furthermore, we observed that risk factors could be mitigated (moderating shield effect) or exacerbated (moderating aggravating effect) once moderated by positive or negative appraisals respectively. When risk factors are moderated by negative appraisals, they become highly predictive of parental burnout and put the parent at higher risk for the condition.

Hence, the results related to the mediation and the moderation analyses convey the compelling message that sociodemographic and situational risk factors for parental burnout do not represent such a heavy risk for parental burnout, unless they are mediated and/or moderated by cognitive processes tinged with negativity. Although preliminary, these results call for additional experimental studies that would refine our understanding of the mediation and moderation role of cognitive appraisals in parental burnout. If cognitive appraisals are systematically found to play both a mediation and a moderation role, it will be further informative to conduct research that would seek to find out how these two mechanisms can be combined in a unique model.

This research represents a milestone since it reveals that cognitive processes, and more specifically, cognitive appraisals, are truly and importantly operative in parental burnout. These groundbreaking findings raise significant social and health issues of direct applied relevance and will hopefully be echoed by governmental authorities. It is high time policymakers allocated additional resources to social, clinical and educational sectors whose task would consist in highlighting the efficacy and the qualities of the individual in his or her parenting role (breeding ground for positive cognitive appraisals) instead of focusing primarily on the aspects that have yet to be improved (breeding ground for negative cognitive appraisals). Likewise, positive psychology can make an important contribution to the joint endeavor by helping parents to hold generalized favorable expectancies about their parenting competences and by calling upon their self-benevolence and self-compassion; powerful pathways towards lightening the crippling burden imposed by the omnipresence of moralizing positive parenting policy campaigns.

These findings also demand a revision of the current etiological model of parental burnout (Mikolajczak & Roskam, 2018): cognitive appraisals should be integrated in the model. More than the objective imbalance between stressors and resources, our results suggest that it is the perceived imbalance between stressors and resources that leads to parental burnout.

Revisiting the essence of the genesis of parental burnout in the light of cognitive appraisals has the potential to bring about crucial advances in the domain of parental burnout research, which will not only serve cognitive science (Mikolajczak et al., 2021) but will also provide new avenues for prevention programs and effective treatments.

Limitations and Future Directions

Although this paper breaks new ground by showing the mediating and moderating role of cognitive appraisals in parental burnout, important limitations arise from this cross-sectional and observational study. First, the subjects displaying missing data on the variables of interest in the study were listwise deleted. Therefore, we cannot exclude that a bias was introduced. Second, the underrepresentation of fathers in our sample makes it difficult to generalize our results. Long-established gender roles often give mothers more agency when it comes to parenting topics. This might be the key to understanding why there was much less incentive for fathers to enroll in the study (and in parenting studies more generally). Third, the study design does not allow to infer causation directions. Whether cognitive appraisals might be truly predictive of parental burnout, and whether they should be considered as a cause or as a consequence of parental burnout hence remains unclear. Finally, the cognitive appraisals measure would gain in robustness by investigating both primary appraisals (relevance of the stressful situation to the individual) and secondary appraisals (coping potential of the individual) instead of just relying on a general positive versus negative interpretation of the situation. Despite the aforementioned limitations, the study paves the way for further promising research that would probe the role of cognitive processes in parental burnout. In that respect, this study calls for follow-up experimental studies that would manipulate the parents’ cognitive appraisals.

Concluding Comment

The present study revealed that objective sociodemographic characteristics are hardly any more predictive of parental burnout in a context of lockdown than usual. It further showed that situational factors (or the specific restrictive living conditions associated with the lockdown due to the Covid-19 pandemic) also constitute a poor candidate for the prediction of parental burnout. By contrast, cognitive appraisals were found to play a crucial mediating and moderating role in parental burnout. These findings pressingly call for research at the intersection of cognitive and applied sciences.

Data Availability

The analysis plan, methodology and a description of the dataset was preregistered on the Open Science Framework (OSF). De-identified data, Supplementary Material, SPSS 26 and Stata 16 syntaxes used for analyses are shared publicly on OSF at https://osf.io/x7vhc/?view_only=0d5e4f78e57442d3b73fb4a00f749cdb

References

Aafjes-van Doorn, K., Kamsteeg, C., & Silberschatz, G. (2020). Cognitive mediators of the relationship between adverse childhood experiences and adult psychopathology: A systematic review. Development and Psychopathology, 32(3), 1017–1029. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579419001317

Arikan, G., Üstündağ‐Budak, A. M., Akün, E., Mikolajczak, M., & Roskam, I. (2020). Validation of the Turkish version of the Parental Burnout Assessment (PBA). New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1002/cad.20375

Arnold, M. B. (1960). Emotion and personality. Columbia University Press.

Ayduk, O., Mischel, W., & Downey, G. (2002). Attentional mechanisms linking rejection to hostile reactivity: The role of “hot” versus “cool” focus. Psychological Science, 13(5), 443–448. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00478

Brianda, M. E., Roskam, I., Gross, J. J., Franssen, A., Kapala, F., Gérard, F., & Mikolajczak, M. (2020a). Treating parental burnout: Impact of two treatment modalities on burnout symptoms, emotions, hair cortisol, and parental neglect and violence. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics., 89(5), 330–332. https://doi.org/10.1159/000506354

Brianda, M. E., Roskam, I., & Mikolajczak, M. (2020b). Hair cortisol concentration as a biomarker of parental burnout. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 117, 104681. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2020.104681

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Erlbaum.

Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S. G., & Aiken, L. S. (2013). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. Routledge.

Christler, J. C. (2013). Womanhood is not as easy as it seems: Femininity requires both achievement and restraint. Psychology of Men and Masculinities, 14(2), 117–120. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031005

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 499–512. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.499

Eid, M., Gollwitzer, M., & Schmitt, M. (2011). Statistik und Forschungsmethoden Lehrbuch. Beltz.

Gannagé, M., Besson, E., Harfouche, J., Roskam, I., & Mikolajczak, M. (2020). Parental Burnout in Lebanon: Validation Psychometric Properties of the Lebanese Arabic Version of the Parental Burnout Assessment. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 1– 15. https://doi.org/10.1002/cad.20383

Hansotte, L., Nguyen, N., Roskam, I., Stinglhamber, F., & Mikolajczak, M. (2020). Are all burned out parents neglectful and violent? A latent profile analysis. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-020-01850-x

IBM Corp. (2020). IBM SPSS Statistics for Macintosh, Version 27.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.

Lazarus, R. S. (1991). Emotion and adaptation. Oxford University Press.

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer Publishing Company.

Lebert-Charron, A. (2020). Le burnout parental : Etudes des facteurs associés, rôle du conjoint, mise à l’épreuve du modèle transactionnel et identifications de profils de mères à risque. Unpublished doctoral Dissertation, Université Paris-Descartes, France.

Matias, M., Aguiar, J., César, F., Braz, C. A., Barham, E. J., Leme, V., … , Fontaine, A. M. (2020). The Brazilian–Portuguese version of the Parental Burnout Assessment: Transcultural adaptation and initial validity evidence. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 1– 17. https://doi.org/10.1002/cad.20374

Meeussen, L., & Van Laar, C. (2018). Feeling pressure to be a perfect mother relates to parental burnout and career ambitions. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 2113. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02113

Mikolajczak, M., Brianda, M. E., Avalosse, H., & Roskam, I. (2018a). Consequences of parental burnout: Its specific effect on child neglect and violence. Child Abuse & Neglect, 80, 134–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.03.025

Mikolajczak, M., Gross, J. J., & Roskam, I. (2019). Parental burnout: What is it and why does it matter? Clinical Psychological Science, 7, 1319–1329. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702619858430

Mikolajczak, M., Gross, J. J., & Roskam, I. (2021). Beyond job burnout: Parental burnout! Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 25(5), 333–336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2021.01.012

Mikolajczak, M., Gross, J. J., Stinglhamber, F., Lindahl Norberg, A., & Roskam, I. (2020). Is parental burnout distinct from job burnout and depressive symptoms? Clinical Psychological Science, 8(4), 673–689. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702620917447

Mikolajczak, M., & Luminet, O. (2008). Trait emotional intelligence and the cognitive appraisal of stressful events: An exploratory study. Personality and Individual Differences, 44(7), 1445–1453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2007.12.012

Mikolajczak, M., Raes, M. E., Avalosse, H., & Roskam, I. (2018b). Exhausted parents: Sociodemographic, child-related, parent-related, parenting and family-functioning correlates of parental burnout. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27(2), 602–614. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0892-4

Mikolajczak, M., & Roskam, I. (2018). A theoretical and clinical framework for parental burnout: The balance between risks and resources (BR2). Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 886. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00886

Mousavi, S.F., Mikolajczak, M., & Roskam, I. (2020). Parental burnout in Iran: Psychometric properties of the Persian (Farsi) version of the parental burnout assessment (PBA). New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 1– 16. https://doi.org/10.1002/cad.20369

Parkes, A., Sweeting, H., & Wight, D. (2015). Parenting stress and parent support among mothers with high and low education. Journal of Family Psychology, 29(6), 907. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000129

Roskam, I., Aguiar, J., Akgun, E., Arikan, G., Artavia, M., Avalosse, H., Aunola, K., Bader, M., Bahati, C., Barham, E. J., Besson, E., Beyers, W., Boujut, E., Brianda, M. -E., Brytek-Matera, A., Carbonneau, N., César, F., Bhen, B. B., Dorard, G., … Mikolajczak, M. (2021). Parental burnout around the globe: A 42-country study. Affective Science. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42761-020-00028-4

Roskam, I., Brianda, M. E., & Mikolajczak, M. (2018). A step forward in the conceptualization and measurement of parental burnout: The Parental Burnout Assessment (PBA). Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 758. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00758

Schneider, T. R. (2004). The role of neuroticism on psychological and physiological stress responses. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 40(6), 795–804. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2004.04.005

Stănculescu, E., Roskam, I., Mikolajczak, M., Muntean, A., & Gurza, A. (2020). Parental burnout in Romania: Validity of the Romanian version of the parental burnout assessment (PBA‐RO). New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 1–18. 10.1002.cad.20384

StataCorp. (2019). Stata Statistical Software: Release 16. StataCorp LLC.

Szczygieł, D., Sekulowicz, M., Kwiatkowski, P., Roskam, I., & Mikolajczak, M. (2020). Validation of the Polish version of the Parental Burnout Assessment (PBA). New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 1‐22. https://doi.org/10.1002/cad.20385

Tong, E. M. (2010). Personality influences in appraisal–emotion relationships: The role of neuroticism. Journal of Personality, 78(2), 393–417. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2010.00620.x

Van Bakel et al., (n.d.) in preparation.

Funding

A.W. is a Research Fellow of the Fonds de la Recherche Scientifique – FNRS. This fund did not exert any influence or censorship on the present work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

On the initiative of Hedwig van Bakel (H.v.B.), Isabelle Roskam (I.R.) and Moïra Mikolajczak (M.M.) collected the data, developed the study concept and design. I.R. and Aline Woine (A.W.) performed the data analyses and interpretation. I.R. and A.W. drafted the manuscript. M.M., James Gross (J.G.) and H.v.B. provided revisions. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

M.M. and I.R. founded the Training Institute for Parental Burnout (TIPB) which trains professionals on parental burnout. The TIPB did not participate in the funding of this study, nor did it influence the process or the results in any way.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the ethical committee of the UCLouvain in Belgium and was carried out in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

ESM 1

(PDF 601 KB)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Woine, A., Mikolajczak, M., Gross, J. et al. The role of cognitive appraisals in parental burnout: a preliminary analysis during the COVID-19 quarantine. Curr Psychol 42, 30585–30598 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02629-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02629-z