Abstract

DSM-5 classifies Selective Mutism (SM) among anxiety disorders, and a majority of children with SM comply with symptomatology of Social Anxiety Disorder (SAD). It is still discussed whether SM constitutes a discrete disorder entity or merely an extreme form of SAD. Past research that compared anxiety levels in both disorders resulted in conflicting conclusions, which might be due to the adoption of questionnaire measures or experimental designs that comprised in vivo situations. In vivo situations contain the possibility to avoid the feared situations for children with SM by remaining silent, which is not true for children with SAD. Participants aged eight to 18 years (M = 13.30 years, SD = 3.26) with above cut-off symptomatology in SM (n = 52), SAD (n = 18), and typical development (n = 41) participated in an online-based study. They evaluated 21 videos with neutral, embarrassing, or speech-demanding situations with respect to their anxiety elicitation. There was no general difference in anxiety levels between participants with elevated SM and SAD symptomatology, and both groups rated embarrassing situations similarly. However, only children with SM features experienced speech-demanding situations as anxiety eliciting, as embarrassing situations and more so than participants in both other groups. Results of the present study indicate that SM is an anxiety disorder with a specific anxiety pattern rather than an extreme form of SAD. In addition to typical social phobic situations, interventions for children with SM should also address situations involving speech demands.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Selective Mutism (SM) is a mental disorder comprising symptoms of consistent failure to speak in certain social situations despite speaking in others (American Psychiatric Association 2013). The fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) classified SM among anxiety disorders for the first time. This decision was based on a significant number of studies indicating anxiety as a central phenomenon of SM, a common etiology between SM and other anxiety disorders, as well as results from initial treatment studies (Muris and Ollendick 2015). The disorder is associated with the child’s severely impaired psychosocial functioning in several social contexts, and both social and educational development can be influenced considerably (Bergman et al. 2002).

Particularly, the relationship between SM and SAD has been discussed controversially. Social Anxiety Disorder is characterized by fear of a negative evaluation by others due to assumed embarrassing behavior in a social situation (American Psychiatric Association 2013). The high comorbidity rate of SAD in children with SM gives us an initial indication of major overlap between these disorders (Bergman et al. 2013; Gensthaler et al. 2016b; Levin-Decanini et al. 2013; Muris and Ollendick 2015). However, while some researchers assume SM to be an extreme form of SAD with remaining silent as an avoidance mechanism, others believe the disorders to be separate entities with a significant overlap. So far, research results provide mixed results regarding this discussion.

Some results suggest that SM is an extreme form of SAD (Black and Uhde 1995; Carbone et al. 2010; Muris et al. 2016). In clinical interviews conducted with the parents present, it was determined that children with SM had a higher rate of anxiety than children with SAD. The results were the same during experimental tasks given by independent observers. (Yeganeh et al. 2006; Yeganeh et al. 2003; Young et al. 2012). Furthermore, SM and SAD are thought to share similar etiological factors. Here, behavioral inhibition was found to be a strong predictor for both disorders (Biederman et al. 2001; Gensthaler et al. 2016a; Muris et al. 2016). In a retrospective parent-rated questionnaire (Gensthaler et al. 2013), children with SM were rated to be more behaviorally inhibited than children with SAD. Additionally, increased prevalence of a cluster of related disorders including SM, SAD, and shy/anxious personality traits was detected in family members of patients with SM, revealing an overlapping genetic etiology (Chavira et al. 2007; Kristensen and Torgersen 2001; Sharp et al. 2007; Stein et al. 2011). Furthermore, comparable parenting features such as overprotection and control were found to be associated with both disorders (Muris and Ollendick 2015). One common methodological feature of the studies that speak in favor of SM as an extreme form of SAD is that they are exclusively based on other-ratings.

Nevertheless, other findings contradict that assumption, implying that SM and SAD display two discrete entities of disorders. According to this concept it is assumed that SM and SAD do indeed overlap considerably but that they also significantly differ regarding specific characteristics (Manassis et al. 2003). Most importantly, it is supposed that anxiety levels are comparable between both disorders. The most convincing research findings supporting this assumption are those addressing comorbidities in children with SM compared to SAD. One recent study systematically compared the comorbidity profiles of children with SM and SAD with a standardized clinical interview. It was found that children with SM had Separation Anxiety Disorder and Oppositional Defiant Disorder as well as Agoraphobia during adolescence more frequently than participants with SAD. In contrast, the latter exhibited Major Depression and Generalized Anxiety disorder more frequently than participants with SM (Gensthaler, Maichrowitz, et al. 2016). A latent class analysis on behavior symptoms in children with SM found only a small group of n = 16 to be exclusively anxious (Cohan et al. 2008). The majority of children with SM were found to additionally display symptoms of mild oppositional behavior (n = 58) or delayed communication (n = 56). In direct comparison, children with SM were found to exhibit more language related impairments than those with SAD (Manassis et al. 2003; McInnes et al. 2004). Furthermore, studies that assessed anxiety levels using self- and parent- and teacher-rated questionnaires indicated comparable levels of social anxiety in both groups (Manassis et al. 2003; McInnes et al. 2004; Yeganeh et al. 2003; Young et al. 2012; Levin-Decanini et al. 2013; Viana et al. 2009), which conflicts with the assumption that SM is an extreme form of SAD. From a methodological point of view, and most importantly for the current study, it can be noted that studies incorporating self-ratings of the children indicate comparable levels of anxiety rather than SM to be an extreme form of SAD.

A major shortcoming of some of the previously mentioned studies is associated with the susceptibility to over−/underreporting of anxiety levels in self- and other ratings. Here, quasi-experimental studies with the emphasis to compare anxiety levels between children with SM and SAD would provide a more objective insight. The only quasi-experimental study conducted so far compared children with SM and SAD regarding psychophysiological measures in a role-play and read-aloud paradigm (Young et al. 2012). Surprisingly, while children with SAD displayed elevated changes in skin conductance and blood pressure, children with SM did not differ from typically developing peers. However, it cannot be ruled out that the results of this in-vivo designed study are due to the effective avoidance of anxious arousal, since all children with SM failed to speak during the role-play. Due to this confounding variable, results must be interpreted with caution.

Taken together, there is evidence of both models, SM as an extreme form of SAD as well as separate entities with significant overlap. Only one study addressed this topic with an quasi-experimental study design so far, however, the in-vivo task was confounded by active avoidance of children with SM. Furthermore, sample sizes in many studies were small due to the difficult recruitment of children with SM, and significant differences might not have been found due to lack of power. The current quasi-experimental study was designed with the aim to compare children with SM and SAD, both, to each other and to typically-developing children with respect to anxiety levels in different social situations which were presented in-sensu in order to rule out effective avoidance in children with SM. Study participants rated the anxiety-eliciting potential of different video clips of embarrassing, speech-demanding or neutral situations we had shown them. In accordance with studies that have directly addressed the children with the help of self-ratings, we expected children with SM to rate the videos with embarrassing situations as being comparably anxiety-eliciting as children with SAD. Furthermore, we assumed children with SM to rate speech-demanding situations as more anxiety provoking than children with SAD and typically-developing children.

Materials and Methods

Sample

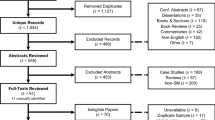

Initially, n = 888 participants started the online-survey, of which n = 264 finished it. Of these 264 participants, n = 153 were younger than 8 years of age and therefore did not take part in the video rating which required reading skills. Therefore, our final sample consisted of n = 111 children and adolescents (n = 84 female) with n = 52 participants with above threshold SM symptoms, n = 18 participants with above threshold SAD symptoms, and n = 41 typically-developing participants (TD). All participants were aged between eight and 18 years (M = 13.30 years, SD = 3.26). Descriptive information on the different groups is found in Table 1. There were no between-group differences in age, gender, or multilingualism. However, more children in the SM group were reported to have experienced delayed speech development than those in the SAD group. Furthermore, children with SM demonstrated more SM-specific symptomatology (FSSM severity scale) than all other groups, while social phobic symptomatology (SPAIK) in the SM and SAD groups was similar.

Participants were assigned to the SM group if they scored above the clinical cut-off in a questionnaire for diagnosing SM (FSSM) regardless of their score on a questionnaire for SAD (SPAIK). To be assigned to the SAD group, the SAD questionnaire’s score had to be above the clinical cut-off for that diagnosis. Finally, participants were assigned to the group TD if neither score was above the relevant cut-off. Inclusion criteria comprised an age of the child between eight and 18 years as well as the ability to read. An exclusion criterion for the group TD was any mental disorder indicated by their parents.

Procedure

All children and their parents participated in an anonymous online-based study conducted with the help of UNIPARK software. The survey was advertised through different media such as mental health professionals, inpatient and outpatient clinics, newspapers, online-forums, and schools. It was indicated on flyers that children and one parent were needed to participate in the study. Initially, participants and their parents were informed about the study, and informed consent was given by button press. Parents had to answer several questions first. During the second part, children were asked to execute tasks that consisted of questions as well as the ratings of different video clips. Parents were instructed not to get involved in their child’s task and to let them answer the questions independently. The study was approved by our local Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Psychology and Sports Science of the University of Giessen (Germany).

Assessment

Frankfurt Scale of Selective Mutism (FSSM) (Gensthaler et al. 2018)

The Frankfurt Scale of Selective Mutism (FSSM) is a parent-rated questionnaire developed to diagnose and evaluate Selective Mutism in children aged between three and 18 years. There are different versions for kindergarteners aged 3 to 7 years, schoolchildren aged 6 to 11 years, and teens aged 12 to 18 years. The questionnaire consists of a Diagnostic Scale with ten yes-no questions about the children’s overall speaking behavior. A score of 7 and higher indicates Selective Mutism. The Severity Scale comprises 41 or 42 questions regarding the specific speaking behavior at kindergarten/school, in public, and at home that are answered on a 5-point-Likert-Scale. An evaluation of the FSSM revealed excellent reliability scores (α = .90–.98) and validity with a one-factor solution for the Severity Scale (Gensthaler et al. 2018). The diagnostic scale differentiates excellently between children with SM and a combined group of children with SAD, internalizing disorders and control children with sensitivities of 94% to 97% and specificities of 90% to 95% (AUC = .97 to .99) (Gensthaler et al. 2018). In the current study, we applied the sum score of the Diagnostic Scale (range 0–10) and the Severity Scale’s relative score (range 0–1). The age appropriate version (either FSSM 6–11 or FSSM 12–18) for each participant was applied. In the current study, reliability coefficients were high with α = .927 (FSSM 6–11), respectively α = .926 (FSSM 12–18) for the Diagnostic Scale and α = .927 (FSSM 6–11), respectively α = .978 (FSSM 12–18) for the Severity Scale.

Social Phobia and Anxiety Inventory for Children (German version: SPAIK) (Melfsen and Warnke 2001)

The German version of the Social Phobia and Anxiety Inventory for children (SPAIK) was adopted to assess symptoms of social phobia and social anxiety in participants. This self-rated questionnaire consists of 26 items defining various social situations in children and adolescents aged eight to 17 years. Somatic, cognitive, and behavioral reactions to these situations are assessed on a 3-point-Likert-Scale. Past research has indicated good reliability (α = .92) and validity, and a cut-off-value of 20 resulted in good discrimination between children with and without Social Anxiety. The total sum-score was used for this study (range 0–52).

Experimental Video Task

During the experimental video task, participants were confronted with 21 short video clips lasting eight to 29 s that they were asked to rate with respect to their anxiety elicitation. An “anxiety thermometer” served this purpose. Children were instructed to indicate on the thermometer how much fear they would feel if they were in the same situation as the protagonist in the video (from 0 = no anxiety to 10 = great anxiety). All video clips were created with the help of amateur actors who re-enacted typical school situations. The video clips were shot from the first-person perspective of one of the students in the classroom. Video clips were presented in random order. Six video clips yielded neutral non-embarrassing situations without any verbal demands for the protagonist (e.g., the entire class is watching a film). Another six video clips demonstrated embarrassing situations without verbal demands for the protagonist (e.g., the protagonist’s pencil case accidently falls down, makes a loud noise, and everybody looks at him). Finally, the remaining nine video clips showed non-embarrassing situations including verbal demands (e.g., the teacher asks the protagonist to read a text aloud).

Statistical Analysis

In the first step, a factor analysis was conducted of the children’s ratings on the 21 video clips to see whether they revealed the intended structure. A principal component analysis (PCA) with oblimin rotation was conducted. All anti-image-correlations were > .85, and the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin coefficient was .93, indicating adequate sampling for the factor analysis. The factor extraction was executed with the help of the elbow-criterion, resulting in a three-factor solution.

According to the factor solution, means for the resulting factors were calculated and compared between groups in an analysis of variances (mixed ANOVA) with the independent factor group (SMxSADxTD) and dependent factor video category (AxBxC). Post-hoc-tests (two-tailed) were conducted for significant main effects and interactions with corrections for multiple testing according to Bonferroni.

Results

Factor loadings of the three-factor solution, together with a short description of the video content, are illustrated in Table 2.

Altogether, 69.40% of the variance was explained by this solution. All but one video loaded on the original category. A closer inspection of the video content indicated that the situation, although nonverbal, was not as embarrassing for the protagonist as the other nonverbal videos. Therefore, the video was removed from further calculations, resulting in the evaluation of 20 videos (6× neutral, 5× embarrassing, 9× verbal). Means and standard deviations for children with SM characteristics, SAD characteristics, and TD are found in Table 3. In order to control for potential influences of age on the video ratings, bivariate correlations between age and the three category ratings were conducted. Age did not correlate significantly with the rating of the neutral videos (r = .011, p = .906) nor with the ratings of the embarrassing (r = .021, p = .829) or speech-demanding (r = −.026, p = .787) video ratings. Therefore, age was not included as a covariate in the further analysis.

Analysis of variances resulted in an effect of group (F(2,108) = 31.36, p < .001, d = 1.53), an effect of video category (F(2,216) = 137.64, p < .001, d = 2.26) and a significant interaction effect group x video category F(4,216) = 10.18, p < .001, d = .87) with large effect sizes throughout. Post-hoc tests for the factor group indicated that both children in the SM and SAD groups provided higher anxiety ratings than the TD group (p < .001), at the same time, anxiety ratings by SM and SAD did not differ (p = .319). Post-hoc tests for the dependent factor video category yielded significant differences between the anxiety ratings among the three videos (all p < .001) with the lowest ratings for the neutral videos and highest ratings for the embarrassing videos. Finally, the interaction effect is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Figure 1 shows that the SM and SAD groups rated the embarrassing videos similarly in terms of their anxiety-eliciting, while the SM group rated the videos containing verbal demands highest. Dependent post-hoc tests for each group indicated that with an alpha-correction for multiple testing (α = .002), children with SM rated verbal and embarrassing videos similarly (p = .013) while the TD group’s ratings of the neutral and verbal videos did not differ (p = .021). All other video ratings differed significantly (p < .001) on the corrected alpha level. Independent t-tests between two groups (alpha corrected; α = .002) indicated similar ratings from the SM and SAD groups of neutral (p = .309) and embarrassing (p = .864) videos and from the SAD and TD groups of neutral videos (p = .008). All other comparisons were significant (p < .001) despite alpha adjustment.

Discussion

The present quasi-experimental study was designed to compare anxiety levels in children with SM features, SAD features, and TD in in sensu presented social situations entailing different levels of embarrassment and verbal demands. By adopting this experimental procedure, we were able to rule out effective avoidance of children with SM by remaining silent during speech demanding situations and to obtain sophisticated patterns of anxiety levels in different social situations beyond general trait anxiety symptoms that are usually assessed by adopting questionnaires.

In line with our hypothesis and the assumption that SM and SAD are separete entities with overlapping symptomatology, children with SM and SAD features did not exhibit different levels of anxiety in general: Participants with SM and SAD symptoms rated videos containing embarrassing situations higher and as being similarly anxiety-eliciting than did the TD group. Moreover, the SM and SAD groups’ self-ratings differed in neither the social anxiety questionnaire nor their total anxiety rating across all videos. This result is in line with studies that indicated comparable levels of social anxiety in both groups with the help of self- and parent- and teacher-rated questionnaires (Manassis et al. 2003; McInnes et al. 2004; Yeganeh et al. 2003; Young et al. 2012) (Levin-Decanini et al. 2013; Viana et al. 2009). This finding is the first quasi-experimental proof of a phenomenological overlap between these disorders in their social phobic symptomatology on the one hand and of the assumption that SM is not an extreme form of SAD but characterized by more of a specific pattern of anxiety to certain social situations. Our results contradict the finding from another quasi-experimental study of psychophysiological functioning in children with SM and SAD conducting a role play and performing a read-aloud task (Young et al. 2012). In that study, only participants with SAD exceeded the arousal levels of TD, whose scores resembled those of their SM group. However, in the latter study, children with SM could avoid eliciting arousal by remaining silent, a factor that differs from our study’s protocol, whereby participants experienced the situations in sensu. Furthermore, differences between groups potentially responsible for their findings, as well as extreme standard deviations within groups, make a solid interpretation of their result difficult.

Over and above the evidence of common fear-eliciting situations in children with SM and SAD, our results indicate SM-specific feared situations, namely social situations involving verbal demands even in the absence of an embarrassing component. Children with SM features rated the respective situations to be more anxiety-eliciting than did children in the SAD and TD groups, a result in line with those studies assuming phenomenological differences between the disorders despite their considerable overlap (Gensthaler et al. 2016b; Manassis et al. 2003; McInnes et al. 2004). These differences predominantly concern language-related symptomatology but also differences in a general comorbidity profile. However, the fear of non-embarrassing situations entailing speech-demands does not seem to exclusively affect children with SM features, as those with SAD features rated these situations as being more anxiety-eliciting than neutral situations. Nevertheless, while the children with SM characteristics rated embarrassing and speech-demanding videos alike, we observed a clear difference between the two categories with respect to their anxiety elicitation in the children with SAD features. We therefore believe that these findings reveal a potential difference in cognitive representations of feared situations in children with SM and SAD characteristics. Taken together, our results illustrate comparable anxiety levels between the two disorders regarding overall anxiety to social situations, and specifically the feared situations of being negatively evaluated by others during an embarrassing situation. Additionally, we were able to show differentiating aspects of fear-eliciting situations regarding those with speech-demands which are more pronounced in children with SM features than in those with SAD features.

Our study has several limitations to consider. The main limitations have to do with our anonymous online-based study design. This decision initially originated from the fact that SM is a rather rare disorder and more participants are recruitable nationwide than regionally. Secondly, the threshold for participants in both our SM and SAD groups to participate anonymously and online is lower than it would be for studies in a laboratory, which results in greater representativeness regarding our groups. However, the disadvantages of our online setup are that the participants’ grouping relied solely on questionnaires rather than a comprehensive clinical interview. However, the FSSM was proved to be an excellent measure to differentiate between SM, SAD and typically developing children, as sensitivity and specificity values are at least comparable to those of clinical interviews. Furthermore, we cannot entirely rule out that individuals other than the given child and its parent participated in the study. Additionally, it was not possible to assess comorbidities comprehensively. Considering the comorbidity profile might have given insights into subgroup effects as well as factors that might have had an influence on the anxiety levels of the children beyond the primary psychopathology. Particularly the differentiation between subgroups within the SM group regarding SAD comorbidity (SM-only, SM-SAD-combined) could provide valuable insights into the disorder and could further clarify the relationship between SM and SAD. Therefore, an online-study is a good starting point for the assessment of an understudied disorder like SM to gain some first results that can help us to obtain a matured hypothesis, but this research definitely should be completed by laboratory research with more comprehensive diagnostic assessments that also contain information on other comorbidities.

Another limitation is that girls were over-represented. Although this over-representation applied to all three groups and there were no gender-ratio group differences, this might compromise our results’ generalizability. Lastly, our sample size of participants with SAD features was rather small, and different raters (self vs. parent) filled in the questionnaires for the SM and SAD symptomatology due to availability of alternatives for this large age group. In this connection, one must consider that our study’s children were much older than the average age of SM’s onset. This might limit our study’s representativeness further, because more severely affected and/or chronically impaired children participated. At the same time and from a developmental view, anxiety-related cognitions might be more pronounced in the age group we assessed compared to younger ages.

Conclusion

Children with SM features demonstrate typical social phobic fears to the same extent as children with SAD features but, additionally and to the same extent, fears about speech-demanding situations. Conceptually speaking, this observation supports the assumption that while SM is not an extreme form of SAD, both disorders are distinct entities with an overlap regarding social fears and a specific profile regarding speech demanding situations. Further research might address this difference by adopting a wider range of assessments including both behavioral and psychophysiological measures in the laboratory. Our clinical results indicate that interventions for children with SM should target both fields - typical social phobic situations as well as situations containing speech demands. Therefore, exposure therapy for children with SM should be more comprehensive with respect to target situations than for those with SAD.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5) (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Bergman, R. L., Piacentini, J., & McCracken, J. T. (2002). Prevalence and description of selective mutism in a school-based sample. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 41(8), 938–946. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200208000-00012.

Bergman, R. L., Gonzalez, A., Piacentini, J., & Keller, M. L. (2013). Integrated behavior therapy for selective Mutism: A randomized controlled pilot study. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 51(10), 680–689. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2013.07.003.

Biederman, J., Hirshfeld-Becker, D. R., Rosenbaum, J. F., Hérot, C., Friedman, D., Snidman, N., Kagan, J., & Faraone, S. V. (2001). Further evidence of association between behavioral inhibition and social anxiety in children. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 158, 1673–1679. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.158.10.1673.

Black, B., & Uhde, T. W. (1995). Psychiatric characteristics of children with selective mutism: A pilot study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 34(7), 847–856. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199507000-00007.

Carbone, D., Schmidt, L. A., Cunningham, C. C., McHolm, A. E., Edison, S., St Pierre, J., & Boyle, M. H. (2010). Behavioral and socio-emotional functioning in children with selective Mutism: A comparison with anxious and typically developing children across multiple informants. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 38(8), 1057–1067. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-010-9425-y.

Chavira, D. A., Shipon-Blum, E., Hitchcock, C., Cohan, S., & Stein, M. B. (2007). Selective mutism and social anxiety disorder: All in the family? Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 46(11), 1464–1472. https://doi.org/10.1097/chi.0b013e318149366a.

Cohan, S. L., Charira, D. A., Shipon-Blum, E., Hitchcock, C., Roesch, S. C., & Stein, M. B. (2008). Refining the classification of children with selective Mutism: A latent profile analysis. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 37(4), 770–784. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374410802359759.

Gensthaler, A., Möhler, E., Resch, F., Paulus, F., Schwenck, C., Freitag, C. M., & Goth, K. (2013). Retrospective assessment of behavioral inhibition in infants and toddlers: Development of a parent report questionnaire. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 44(1), 152–165. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-012-0316-z.

Gensthaler, A., Khalaf, S., Ligges, M., Kaess, M., Freitag, C. M., & Schwenck, C. (2016a). Selective mutism and temperament: The silence and behavioral inhibition to the unfamiliar. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 25(10), 1113–1120. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-016-0835-4.

Gensthaler, A., Maichrowitz, V., Kaess, M., Ligges, M., Freitag, C. M., & Schwenck, C. (2016b). Selective Mutism: The fraternal twin of childhood social phobia. Psychopathology, 49(2), 95–107. https://doi.org/10.1159/000444882.

Gensthaler, A., Dieter, J., Raisig, S., Hartmann, B., Ligges, M., Kaess, M., et al. (2018). Evaluation of a novel parent-rated scale for selective Mutism. Assessment, 107319111878732–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191118787328.

Kristensen, H., & Torgersen, S. (2001). MCMI-II personality traits and symptom traits in parents of children with selective mutism: A case-control study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 110(4), 648–652. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-843X.110.4.648.

Levin-Decanini, T., Connolly, S. D., Simpson, D., Suarez, L., & Jacob, S. (2013). Comparison of behavioral profiles for anxiety-related comorbidities including ADHD and selective mutism in children. Depression and Anxiety, 30, 857–864. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22094.

Manassis, K., Fung, D., Tannock, R., Sloman, L., Fiksenbaum, L., & McInnes, A. (2003). Characterizing selective mutism: Is it more than social anxiety? Depression and Anxiety, 18(3), 153–161. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.10125.

McInnes, A., Fung, D., Manassis, K., Fiksenbaum, L., & Tannock, R. (2004). Narrative skills in children with selective Mutism: An exploratory study. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 13(4), 304–315. https://doi.org/10.1044/1058-0360(2004/031).

Melfsen, S., & Warnke, A. (2001). SPAIK. Sozialphobie und -angstinventar für Kinder. Göttingen: Hogrefe.

Muris, P., & Ollendick, T. H. (2015). Children who are anxious in silence: A review on selective Mutism, the new anxiety disorder in DSM-5. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 18, 151–169. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-015-0181-y.

Muris, P., Hendriks, E., & Bot, S. (2016). Children of few words: Relations among selective Mutism, behavioral inhibition, and (social) anxiety symptoms in 3- to 6-year-olds. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 47(1), 94–101. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-015-0547-x.

Sharp, W. G., Sherman, C., & Gross, A. M. (2007). Selective mutism and anxiety: A review of the current conceptualization of the disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 21(4), 568–579. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.07.002.

Stein, M. B., Yang, B. Z., Chavira, D. A., Hitchcock, C. A., Sung, S. C., Shipon-Blum, E., & Gelernter, J. (2011). A common genetic variant in the Neurexin superfamily member CNTNAP2 is associated with increased risk for selective Mutism and social anxiety-related traits. BPS, 69(9), 825–831. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.11.008.

Viana, A. G., Beidel, D. C., & Rabian, B. (2009). Selective mutism: A review and integration of the last 15 years. Clinical Psychology Review, 29(1), 57–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2008.09.009.

Yeganeh, R., Beidel, D. C., Turner, S. M., Pina, A. A., & Silverman, W. K. (2003). Clinical distinctions between selective Mutism and social phobia: An investigation of childhood psychopathology. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 42(9), 1069–1075. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.CHI.0000070262.24125.23.

Yeganeh, R., Beidel, D. C., & Turner, S. M. (2006). Selective mutism: More than social anxiety? Depression and Anxiety, 23(3), 117–123. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20139.

Young, B. J., Bunnell, B. E., & Beidel, D. C. (2012). Evaluation of children with selective Mutism and social phobia a comparison of psychological and psychophysiological arousal. Behavior Modification, 36(4), 525–544. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145445512443980.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

All authors have no financial relationships to disclose and declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schwenck, C., Gensthaler, A. & Vogel, F. Anxiety levels in children with selective mutism and social anxiety disorder. Curr Psychol 40, 6006–6013 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00546-w

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00546-w