Abstract

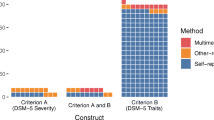

The DSM-5 creation process and outcome underlines a core tension in psychiatry between empirical evidence that mental pathologies tend to be dimensional and a historical emphasis on delineating categorical disorders to frame psychiatric thinking. The DSM has been slow to reflect dimensional evidence because doing so is often perceived as a disruptive paradigm shift. As a result, other authorities are making this shift, circumventing the DSM in the process. For example, through the Research Domain Criteria (RDoC), NIMH now encourages investigators to focus on a dimensional and neuroscientific conceptualization of mental disorder research. Fortunately, the DSM-5 contains a dimensional model of maladaptive personality traits that provides clinical descriptors that align conceptually with the neuroscience-based dimensions delineated in the RDoC and in basic science research. Through frameworks such as the DSM-5 trait model, the DSM can evolve to better incorporate evidence of the dimensionality of mental disorder.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance

Widiger TA, Simonsen E, Krueger RF, Livesley JW, Verheul R. Personality disorder research agenda for the DSM-V. J Pers Disord. 2005;19:315–38.

Brown TA, Campbell LA, Lehman CL, Grisham JR, Mancill RB. Current and lifetime comorbidity of the DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders in a large clinical sample. J Abnorm Psychol. 2001;110:585–99.

Kupfer DJ, Kuhl EA, Regier DA. DSM-5—the future arrived. JAMA. 2013;309(16):1691–2. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.2298. Reviews efforts of the DSM-5 Task Force co-chairs (Kupfer and Regier) to make DSM better reflect evidence of the dimensional nature of psychopathology.

Whooley O, Horwitz AV. The paradox of professional success: grand ambition, furious resistance, and the derailment of the DSM-5 revision process. In: Paris J, Philips J, editors. Making the DSM-5: concepts and controversies. New York: Springer; 2013. p. 75–92.

Verheul R. Clinical utility of dimensional models for personality pathology. J Pers Disord. 2005;19:283–302.

Skodol AE, Morey LC, Bender DS, Oldham JM. The ironic fate of the personality disorders in DSM-5. Personal Disord. 2013;4:342–9. doi:10.1037/per0000029.

Morey LC, Skodol AE, Oldham JM. Clinician judgments of clinical utility: a comparison of DSM-IV-TR personality disorders and the alternative model for DSM-5 personality disorders. J Abnorm Psychol. 2014;123:398–405. doi:10.1037/a0036481.

Lilienfeld SO, Waldman ID. Comorbidity and chairman Mao. World Psychiatry. 2004;3:26–7.

Maj M. ‘Psychiatric comorbidity’: an artifact of current diagnostic systems? Br J Psychiatry. 2005;186:182–4.

Krueger RF, Hopwood CJ, Wright, AGC, Markon KE. DSM-5 and the Path toward Empirically Based and Clinically Useful Conceptualization of Personality and Psychopathology. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2014;21(3):245–261. doi:10.1111/cpsp.12073

Gunderson JG. Introduction to section IV: personality disorders. In: Widiger TA, Frances A, Pincus H, et al., editors. DSM IV sourcebook, vol. 2. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1996.

Eaton N, Krueger RF, Keyes KM, Skodol AE, Markon KE, Grant BF, et al. Borderline personality disorder co-morbidity: relationship to the internalizing-externalizing structure of common mental disorders. Psychol Med. 2011;41:1041–50.

James LM, Taylor J. Revisiting the structure of mental disorders: borderline personality disorder and the internalizing/externalizing spectra. Br J Clin Psychol. 2008;47:361–80.

Ramos V, Canta G, deCastro F, Leal I. Discrete subgroups of adolescents diagnosed with borderline personality disorder: a latent class analysis of personality features. J Pers Dis. 2014. In press.

Conway C, Hammen C, Brennan P. A comparison of latent class, latent trait, and factor mixture models of DSM-IV borderline personality criteria in a community setting: implications for DSM-5. J Pers Disord. 2012;26:793–803.

Hallquist MN, Wright AGC. Mixture modeling methods for the assessment of normal and abnormal personality part I: cross-sectional models. J Pers Assess. 2014;96(3):256–68.

Haslam N, Holland E, Kuppens P. Categories versus dimensions in personality and psychopathology: a quantitative review of taxometric research. Psychol Med. 2012;42:903–20.

Ahmed AO, Green BA, Goodrum NM, Doane NJ, Birgenheir D, Buckley PF. Does a latent class underlie Schizotypal personality disorder? Implications for schizophrenia. J Abnorm Psychol. 2013;122:475–91.

Kendler KS, Myers J. The boundaries of the internalizing and externalizing genetic spectra in men and women. Psychol Med. 2014;44(3):647–55. doi:10.1017/S0033291713000585

Eaton NR, Krueger RF, Markon KE, Keyes K, Skodol AE, Wall M, et al. The structure and predictive validity of the internalizing disorders. J Abnorm Psychol. 2013;122:86–92.

MacDonald III AW, Krueger RF. Mapping the country within: a special section on reconceptualizing the classification of mental disorders. J Abnorm Psychol. 2013;122:891–3.

Maj M. Keeping an open attitude towards the RDoC project. World Psychiatry. 2014;13:1–3.

Trull TJ, Widiger TA. Dimensional models of personality: the five factor model and the DSM-5. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2013;15:135–46.

Costa Jr PT, Widiger TA. Personality disorders and the five-factor model of personality. 3rd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2012.

Harkness AR, McNulty JL. The Personality Psychopathology Five (PSY-5): Issues from the pages of a diagnostic manual instead of a dictionary. In: Strack S, Lorr M, editors. Differentiating normal and abnormal personality. New York: Springer; 1994. p. 291–315.

Wright AGC, Simms LJ. On the structure of personality disorder traits: conjoint analyses of the CAT-PD, PID-5, and NEO-PI-3 trait models. Personality Disord: Theory Res Treat. 2014;5:43–54.

Krueger RF, Markon KE. The role of the DSM-5 personality trait model in moving toward a quantitative and empirically based approach to classifying personality and psychopathology. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2014;10:477–501. doi:10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032813-153732. Provides a recent review of empirical literature on the DSM-5 personality trait model.

Shiner RL. The development of personality disorders: perspectives from normal personality development in childhood and adolescence. Dev Psychopathol. 2009;21:715–35.

Adelstein JS et al. Personality is reflected in the brain’s intrinsic functional architecture. PLoS One. 2011;6(11):e27633. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0027633. Provides evidence that aspects of the intrinsic functional organization of the brain reflect major domains of human personality.

First MB. Clinical utility: a prerequisite for the adoption of a dimensional approach in DSM. J Abnorm Psychol. 2005;114(4):560–4.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Conflict of Interest

Robert F. Krueger, Christopher J. Hopwood, and Aidan G. C. Wright declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Kristian E. Markon was an Adviser to the DSM-5 Personality and Personality Disorders Workgroup.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Psychiatric Diagnosis

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Krueger, R.F., Hopwood, C.J., Wright, A.G.C. et al. Challenges and Strategies in Helping the DSM Become More Dimensional and Empirically Based. Curr Psychiatry Rep 16, 515 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-014-0515-3

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-014-0515-3