Background

This meta-analysis examined differences in health-related quality of life (HRQoL) between seekers of surgical and non-surgical treatment, and non-treatment seekers, over and above differences that are explained by weight, age, and gender.

Methods

Our literature search focused on the ‘Impact of Weight on Quality of Life-Lite’ (IWQOL-Lite) and the ‘Short Form-36’ (SF-36) questionnaires. Included were studies published between 1980 and April 2006 providing pre-treatment descriptive statistics of adult overweight, obese or morbidly obese persons. Excluded were elderly and ill patient groups.

Results

54 articles, with a total number of nearly 100,000 participants, met the inclusion criteria. Persons seeking surgical treatment demonstrated the most severely reduced HRQoL. IWQOL-Lite scores showed larger differences between populations than SF-36 scores. After adjustment for weight, the population differences on the IWQOL disappeared. In contrast, the differences on the SF-36 between the surgical treatment seeking population and the other populations were maintained after adjustment for weight.

Conclusion

The IWQOL-Lite questionnaire predominantly reflects weight-related HRQoL, whereas the SF-36 mostly reflects generic HRQoL that is determined by both weight and other factors. Our metaanalysis provides reference values that are useful when explaining or evaluating obesity-specific (IWQOL-Lite) or generic (SF-36) HRQoL, weight, and demographic characteristics of obese persons seeking or not seeking surgical or non-surgical treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

An increasing number of people are facing the burden of obesity, which is defined as a body mass index (BMI) of ≥30 kg/m2.1,2 This worldwide epidemic is a concern to health professionals, because obesity is closely linked to risk factors associated with impaired health, shortened life expectancy,3 and reduced health-related quality of life (HRQoL).4 Our meta-analysis focuses on the impact of obesity on HRQoL. HRQoL is of relevance as an outcome measure in obesity, when treatment options are evaluated in terms of risks and benefits with regard to the health, well-being, and general functioning of the patient. HRQoL may differ among subgroups of obese persons, who seek surgical or non-surgical treatment, or who do not seek treatment for their overweight. Some studies demonstrated greater impairment of HRQoL in people seeking treatment, especially treatment of greater intensity.5–8 The quantification of HRQoL in obese people seeking and not seeking treatment will indicate whether over and above other possible factors such as weight, age, and gender, the HRQoL differs among persons who seek a specific kind of treatment for obesity. In addition, such a quantification will provide reference data that are useful when evaluating the baseline status of obese individuals who apply for weight-reducing interventions.

The literature of the past 26 years was reviewed in order to examine differences in baseline HRQoL between seekers of surgical treatment, seekers of non-surgical treatment, and non-treatment seekers. We additionally investigated the role of weight, age, and gender in the associations between HRQoL and treatment status.

Materials and Methods

Selection of Studies

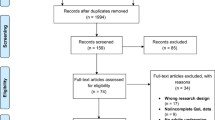

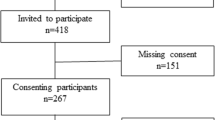

This meta-analysis comprises empirical studies in the English, French, German, or Dutch scientific literature. Included were reports of studies with adult, but not elderly or ill, populations, who were overweight (BMI ≥25 kg/m2), obese (BMI ≥30 kg/m2), or morbidly obese (BMI ≥40 kg/m2) and who were seeking or not-seeking treatment for their weight. Non-empirical studies (dissertations, reviews, and books) were excluded. To be included in the metaanalysis, pre-treatment descriptive statistics of the HRQoL (mean, SD) had to be available in the identified research reports or obtainable from the authors. We limited our search to the frequently used ‘Impact of Weight on Quality of Life-Lite’ (IWQOL-Lite) and ‘Short form-36’ (SF-36) questionnaires. The search strategy for identification of relevant literature was carried out in three phases. Figure A1 (see Appendix) presents the flow diagram. Eligibility was independently determined by two authors (AMAvN, EJMW).

Phase 1. The first phase determined which generic and obesity-specific instruments had been used to assess HRQoL in obese populations. The PubMed and PsycINFO databases were systematically searched from 1980 until April 2006 with the following key words (quality of life) AND (overweight OR obesity). This yielded 1,071 titles from PubMed and 170 titles from PsycINFO. After exclusion of studies with children, elderly, and disease groups as well as non-empirical studies, 432 titles resulted. The abstracts were evaluated to determine whether the article was about HRQoL as related to seeking or not-seeking treatment for overweight or obesity. The remaining 150 abstracts included a wide range of instruments. Only studies that applied the frequently used obesity-specific IWQOLLite questionnaire (18 articles) and the generic SF-36 questionnaire (47 articles) were selected; two articles used both instruments.

Phase 2. The second phase searched additional articles with IWQOL-Lite or SF-36 data for overweight, obese, or morbidly obese persons. The databases Web of Science, PubMed, and PsycINFO were searched until April 2006 with the following search strategy: (Impact of Weight on Quality of Life-Lite OR IWQOL-Lite OR Medical Outcome Survey Short-Form OR Short-Form 36 OR SF-36 OR Rand-36) AND (overweight OR obesity). The search resulted in one additional article that used the IWQOL-Lite and another 14 studies applying the SF-36.

Phase 3. The 82 full text articles of the abstracts identified in phase 2 were scrutinized. The aim of this third phase was to identify articles with the needed descriptive statistics (mean, SD). The authors of 24 studies have sent missing statistics upon request. When more articles of the same author(s) were found, the data were checked for duplications. In case of overlapping data sets, we asked the authors which data were the most recent and complete. This last phase left 54 articles (8 IWQOL-Lite, 44 SF-36, 2 IWQOL-Lite and SF-36) for metaanalysis. All articles were published after 1996.

Instruments

Impact of Weight on Quality of Life-Lite (IWQOLLite). The 31 items of the IWQOL-Lite assess the impact of weight on quality of life in five areas (physical function, self-esteem, sexual life, public distress, work) and additionally yields a total score.5 The five response categories range from “never true” to “always true”. The IWQOL-Lite has adequate psychometric properties: Cronbach’s alphas range from .90 to .94 for the scales and is .96 for the total scale.9 The test-retest stability coefficients range from .81 to .88 for the scales and is .94 for the total scale.10 The validity of the instrument is supported by findings such as sensitivity to weight loss11 and the results of confirmatory factor analysis. 9 The meta-analysis uses transformed scores ranging from 0 to 100, with 100 representing the best and 0 the worst quality of life. A change of 7.7–12 points (depending on baseline severity) on the IWQOL-Lite total transformed score represents a clinically meaningful change.12

Medical Outcomes Study SF-36 Health Status Survey (SF-36). The SF-36 is a 36-item generic questionnaire measuring subjective health status.13 It comprises eight domains of functioning: 1) physical functioning, 2) role limitations due to physical problems, 3) bodily pain, 4) general health, 5) vitality, 6) social functioning, 7) role limitations due to emotional problems, and 8) mental health. Transformed scores range from 0 (poor health) to 100 (good health). The SF-36 has adequate psychometric characteristics, including good construct validity, high internal consistency, and high test-retest stability.13 A population difference of ≥5 points on any scale is considered clinically significant.13

Data Extraction

Five populations were distinguished: 1) the general population, 2) general obese people, 3) non-treatmentseeking obese people, 4) conservative treatment-seeking obese patients, and 5) surgical treatment-seeking obese patients. All populations consisted of several groups, with exception of the non-treatment population, which comprised a single group in both the IWQOL-Lite7 and the SF-368 meta-analysis. Studies recruiting participants from a community sample were considered to belong to the ‘general population’; some of these studies identified groups who were obese or morbidly obese.14–17 Participants who were recruited from the general population specifically because of their obesity were considered to be part of the ‘general obese population’. This ‘general obese population’ differs from the ‘non-treatment-seeking population’ in the sense that non-treatment-seeking persons are known to intentionally choose not to be treated for their obesity. Identified groups in the selected articles were assigned to a population following the recruitment criteria of the original study. The following data were extracted from the selected studies: BMI, age, gender, type of population, and means and standard deviations of the HRQoL variables.

Statistical Analysis

For each population the weighted means of BMI, age, the percentage of women, and HRQoL variables were computed. Inverse variance weights (the sample size divided by the variance) were used as weighing procedure. The METAF.SPS macro18 compared the weighted means of the populations by meta-analytic analog to analysis of variance. We specified the random effects model using the method-of-moments plug in estimate of the METAF.SPS macro for the between-study variance.

To examine the influence of person characteristics on HRQoL, weighted multiple regression using the METAREG.SPS macro (random effects model)18 examined differences between populations before and after adjustment for BMI, age, and gender, respectively. For each analysis, the dichotomized population indicators, i.e., belonging or not belonging to the general obese, non-treatment-seeking, conservative treatment-seeking, or surgical treatment-seeking population, were entered in regression analysis. The BMI, age, and the proportion of female participants were entered in separate analyses to examine the effects of these variables on quality of life. To graphically display the magnitude of differences between populations, effect sizes (statistic d) were computed. These statistics express the deviation from the norm group in standard deviation units.19 Effect size values between 0.2 and 0.5, between 0.5 and 0.8, and >0.8 reflect small, moderate, and large deviations, respectively.19

All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS version 11.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL).

Results

Impact of Weight on Quality of Life-Lite (IWQOL-Lite)

Comparison between Groups. The literature search yielded 27 groups from 11 studies, including over 6,000 individuals: five groups from the general population, 14,20 one non-treatment-seeking group,7 14 conservative treatment-seeking groups,5,14,21–23 and seven surgical treatment-seeking groups.5,7,24–26

No studies of the general obese population were found. Table A1 (see Appendix) shows frequencies and weighted means of the groups. The general, nontreatment, conservative treatment and surgical treatment populations differed significantly from each other with respect to BMI (P<.001) and age (P=.02), but not gender (P=.51). The weighted mean BMI was highest in the surgical treatment population (51 kg/m2), followed by the non-treatment-seeking population (44 kg/m2), the conservative treatment population (37 kg/m2), and the general population (29 kg/m2). The weighted mean age of the non-treatment population (49 yrs) was high as compared to the surgical treatment population (41 yrs), conservative treatment population (40 yrs) and the general population (37 yrs). All populations included considerably more women than men; the percentages of women varied between 68% for the general population and 83% for the surgical treatment population. The four populations differed significantly from each other on all IWQOL-Lite scales (P<.001).

Figure 1 shows the mean deviations from the norm in standard deviation units, effect size d.19 The HRQoL of the general population reflected a moderate to small (−0.8 < d < −0.3) deviation from the norm. The non-treatment and the conservative treatment populations had an intermediate position between the general population and the surgical treatment-seeking population. Mean deviations from the norm were large for the non-treatment-seeking population (−3.3 < d < −2.4) as well as for the conservative treatment population (−3.0 < d < −1.6). The surgical treatment-seeking population (−5.5 < d < −2.8) demonstrated very severely reduced HRQoL scores on all scales.

Adjustment for Weight, Age, and Gender. Table 1 shows the unadjusted mean IWQOL-Lite scores of the populations as well as these scores after adjustment for BMI, age, and gender, respectively. The significance levels with the unadjusted means show that the non-treatment, conservative treatment, and surgical treatment populations have a significantly reduced HRQoL on all dimensions as compared to the other populations. The HRQoL differences between populations fully disappeared after adjustment for BMI. After this adjustment, the surgical treatment population even obtained the best score on public distress. This is probably due to over-correction as a consequence of the very high correlation between BMI and public distress (r = −.90) in this meta-analysis. Adjustment for age and gender did hardly influence the HRQoL scores.

Medical Outcomes Study SF-36 Health Status Survey (SF-36)

Comparison between Groups. For the SF-36, 88 groups from 46 studies were analyzed, involving nearly 88,000 individuals: 35 groups from the general population,15–17,24,27–34 7 groups from the general obese population,35–38 1 non-treatment-seeking group,8 25 groups from the conservative treatmentseeking population,8,30,35–52 and 20 groups from the surgical treatment-seeking population.24,25,53–66

Table A2 (Appendix) shows frequencies and weighted means of the groups. The populations differed from each other with respect to BMI (P<.001) and gender (P=.05), but not age (P=.70). Concerning BMI, non-treatment (33 kg/m2), general obese (35 kg/m2), and conservative treatment (36 kg/m2) populations had an intermediate position between the morbidly obese surgical population (47 kg/m2) and the general population (28 kg/m2). The weighted mean age of the populations varied between 36 years for the non-treatment population and 44 years for the conservative treatment population. All populations included more women than men. The percentages of women varied between 54% for the general obese population and 86% for the surgical treatment population. The five populations differed significantly from each other on all SF-36 scales (P<.001).

Figure 2 shows the deviations from the norm13 in standard deviation units. HRQoL of the general population was about equal to the norm group (−0.1 < d < 0.1). The non-treatment-seeking population (−0.3 < d < 0.0), the general obese population (−0.5 < d < −0.2), and the conservative treatment population (−0.4 < d < −0.2) showed zero to moderate deviations from the norm. The surgical treatment population showed large to moderate deviations from the norm (−1.6 < d < −0.5).

Mean deviation from the norm group in standard deviation units on the SF-36 for five populations. PF: Physical functioning, PR: Physical Role — role limitations due to physical problems, PA: Bodily pain, GH: General health, VI: Vitality, SF: Social functioning, ER: Emotional role — Role limitations due to emotional problems, MH: Mental health.

Adjustment for Weight, Age, and Gender. Table 2 represents the unadjusted mean SF-36 scores of the populations as well as these scores after adjustment for BMI, age, and gender, respectively. The significance levels with the unadjusted means demonstrate that the conservative treatment and surgical treatment populations report a highly significant reduced HRQoL as compared to the other populations. With a few exceptions, after adjustment for BMI, differences between populations disappeared for the non-treatment, conservative treatment, and general obese populations. The exceptions concern the two mental health scales: role limitations due to emotional problems (ER) and Mental Health (MH), which remained low after weight was taken into account. After adjustment for BMI, the surgical treatment population as compared to the other populations still demonstrated a relatively low HRQoL on 5 of the 8 scales. Adjustment for age and gender did not affect the SF-36 HRQoL scores to a large extent.

Discussion

This meta-analysis is the first that summarizes and analyzes HRQoL in diverse obese populations. Studies in well-defined samples provided the data. The strengths of our study are the large sample sizes with the non-treatment-seeking population as the only exception, the geographical diversity of the groups with North and South American, European, Asian, and Australian studies included, and the use of two well-established and validated HRQoL measures. These strengths contribute to the generalizability of the findings. In agreement with several studies, 29,47,54,55 it was shown that obese persons experience a poorer HRQoL compared to the general population. In particular, those seeking surgical treatment reported by far the most severely reduced HRQoL. The results obtained with the two instruments are discussed separately, because of the different results after correction for body weight. IWQOL-Lite quality of life scores of obese populations deviated very much from scores of the norm group. However, these differences disappeared after adjustment for body weight, suggesting that body weight is a main determinant of HRQoL as assessed with this instrument. Our observations suggest that IWQOL-Lite scores will improve after successful weight reduction, as has been reported in two studies.11,20 These previous analyses and our findings indicate the usefulness of the IWQOL-Lite when one aims to explicate or evaluate weight-dependent HRQoL.

In contrast to the IWQOL-Lite, the SF-36 questionnaire suggested a less extreme deviation from the norm for obese populations. Not surprisingly,66 the surgical treatment-seeking obese population demonstrated a large deviation from the norm on virtually all aspects of HRQoL. The reduction in HRQoL for the other obese populations tended to be zero to moderate. Covariance analysis suggested that HRQoL as assessed with this generic instrument is only partly dependent on differences in body weight. In the surgical population, the reduced quality of life on five of the eight dimensions was not solely explained by weight. Also, the reduced scores on the two mental health scales in the general obese population and the conservative treatment population were not explained by weight alone. These findings, therefore, suggest that other factors than weight alone affect the quality of life of obese persons as measured by the SF-36. This result emphasizes the validity of the SF-36 as a partly weight-independent outcome measure for general quality of life.

The current SF-36 findings suggest that obese persons experience limitations in their daily life and work due to emotional problems that are not fully explained by the magnitude of excess weight. An implication of this finding is that weight reduction alone will not suffice when attempting to positively affect mental health of these individuals. A subgroup of obese persons may need specific attention for emotional problems.

In contrast to expectation,5–7 HRQoL as assessed by the IWQOL-lite failed to differ between the populations after adjustment for weight. Also, contrary to expectation, the general obese population and the conservative treatment-seeking population had virtually similar SF-36 scores. Only in the surgical treatment population, reduced physical and role functioning was observed that was not fully explained by weight. This may reflect the impact of co-morbid cardiovascular or joint problems that could be an additional reason to choose for or to be referred to surgical treatment. Overall, our analyses suggest that only in the surgical treatment population, reduced physical functioning is a reason for seeking treatment over and above weight and weight-related quality of life.

Besides weight, age and gender were included as variables in the meta-analysis. Previous studies suggested that obese persons who seek treatment have a higher weight, are older, and are more often female than obese persons not seeking treatment.7,8 Our results consistently confirmed that the weight of the surgical treatment population is higher than the weight of the other populations. No clear findings emerged with respect to age. Although epidemiological studies suggest that there is hardly a sex difference in obesity,1,67 all included populations, and most of all the surgical treatment-seeking population, included more women than men. Thus, especially females who are on average between 40–50 years old are more inclined to participate in research and to seek treatment for their obesity.

A weakness of the present study is that the general obese population is likely to be a rather heterogeneous population including not only persons that do or do not intend to seek treatment for their obesity, but also individuals who choose their own diets or alternative treatments. Another weakness of metaanalytic techniques is that rather homogeneous group means of age and gender are used, whereas multiple regression analysis uses the full range of these variables. Therefore, the possibility that age and gender affect HRQoL is not definitively refuted by our findings. A further major weakness of our study and this specific field in general is that only two studies have investigated the intentionally nontreatment-seeking population.7,8 The small sample size in these studies hampers the generalizability of these findings. Future studies should focus on the non-treatment population, including the large group of non-treatment seeking men, with the aim to examine and analyze the factors which account for their reluctance to seek professional help to reduce weight and to improve health and HRQoL.

In conclusion, both the IWQOL-Lite and the SF-36 findings demonstrate a reduced HRQoL for the obese population, especially for the morbidly obese population seeking surgical treatment. The IWQOL-Lite questionnaire predominantly reveals weight-related quality of life, whereas the SF-36 apparently assesses generic quality of life that is also determined by other factors than weight. Reductions in mental health could not be explained in terms of the magnitude of weight excess alone. This meta-analysis provides reference values that are useful when explaining or evaluating obesityspecific (IWQOL-Lite) and generic (SF-36) health-related quality of life, weight, and demographic characteristics of obese persons seeking or not seeking surgical or non-surgical treatment.

References

Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL et al. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2000. JAMA 2002; 288: 1723–7.

Popkin BM. Global nutrition dynamics: the world is shifting rapidly toward a diet linked with noncommunicable diseases. Am J Clin Nutr 2006; 84: 289–98.

Bray GA. Medical consequences of obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2004; 89: 2583–9.

Jia H, Lubetkin EI. The impact of obesity on health-related quality-of-life in the general adult US population. J Public Health 2005; 27: 156–64.

Kolotkin RL, Crosby RD, Williams GR. Health-related quality of life varies among obese subgroups. Obes Res 2002; 10: 748–56.

Karlsson J, Sjostrom L, Sullivan M. Swedish obese subjects (SOS)–an intervention study of obesity. Two-year followup of health-related quality of life (HRQL) and eating behavior after gastric surgery for severe obesity. Int J Obes 1998; 22: 113–26.

Kolotkin RL, Crosby RD, Pendleton R et al. Health-related quality of life in patients seeking gastric bypass surgery vs non-treatment-seeking controls. Obes Surg 2003; 13: 371–7.

Fontaine KR, Bartlett SJ, Barofsky I. Health-related quality of life among obese persons seeking and not currently seeking treatment. Int J Eat Disord 2000; 27: 101–5.

Kolotkin RL, Crosby RD, Kosloski KD et al. Development of a brief measure to assess quality of life in obesity. Obes Res 2001; 9: 102–11.

Kolotkin RL, Crosby RD. Psychometric evaluation of the impact of weight on quality of life-lite questionnaire (IWQOL-lite) in a community sample. Qual Life Res 2002; 11: 157–71.

Kolotkin RL, Crosby RD, Williams GR et al. The relationship between health-related quality of life and weight loss. Obes Res 2001; 9: 564–71.

Crosby RD, Kolotkin RL, Williams GR. An integrated method to determine meaningful changes in health-related quality of life. J Clin Epidemiol 2004; 57: 1153–60.

Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 1992; 30: 473–83.

Engel S, Kolotkin R, Teixeira P. Psychometric and crossnational evaluation of a Portuguese version of the Impact of Weight on Quality of Life-Lite (IWQOL-Lite) Questionnaire. Eur Eat Disord Rev 2005; 13: 133–43.

Brown WJ, Dobson AJ, Mishra G. What is a healthy weight for middle aged women? Int J Obes 1998; 22: 520–8.

Larsson U, Karlsson J, Sullivan M. Impact of overweight and obesity on health-related quality of life–a Swedish population study. Int J Obes 2002; 26: 417–24.

Huang IC, Frangakis C, Wu AW. The relationship of excess body weight and health-related quality of life: evidence from a population study in Taiwan. Int J Obes 2006; 30: 1250–9.

Lipsey MW, Wilson DB. Practical Meta-analysis. Applied Social Research Method Series, Vol. 49. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications 2001.

Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. New York: Academic Press 1977.

Boan J, Kolotkin RL, Westman EC et al. Binge eating, quality of life and physical activity improve after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity. Obes Surg 2004; 14: 341–8.

Kolotkin RL, Westman EC, Ostbye T et al. Does binge eating disorder impact weight-related quality of life? Obes Res 2004; 12: 999–1005.

Lustig RH, Greenway F, Velasquez-Mieyer P et al. A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dosefinding trial of a long-acting formulation of octreotide in promoting weight loss in obese adults with insulin hypersecretion. Int J Obes 2006; 30: 331–41.

Rieger E, Wilfley DE, Stein RI et al. A comparison of quality of life in obese individuals with and without binge eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord 2005; 37: 234–40.

De Zwaan M, Mitchell JE, Howell LM et al. Two measures of health-related quality of life in morbid obesity. Obes Res 2002; 10: 1143–51.

Dymek MP, Le Grange D, Neven K et al. Quality of life after gastric bypass surgery: a cross-sectional study. Obes Res 2002; 10: 1135–42.

White MA, O’Neil PM, Kolotkin RL et al. Gender, race, and obesity-related quality of life at extreme levels of obesity. Obes Res 2004; 12: 949–55.

Brown WJ, Mishra G, Kenardy J et al. Relationships between body mass index and well-being in young Australian women. Int J Obes 2000; 24: 1360–8.

Burns CM, Tijhuis MA, Seidell JC. The relationship between quality of life and perceived body weight and dieting history in Dutch men and women. Int J Obes 2001; 25: 1386–92.

Doll HA, Petersen SE, Stewart-Brown SL. Obesity and physical and emotional well-being: associations between body mass index, chronic illness, and the physical and mental components of the SF-36 questionnaire. Obes Res 2000; 8: 160–70.

Kaukua J, Pekkarinen T, Sane T et al. Health-related quality of life in obese outpatients losing weight with very-lowenergy diet and behaviour modification — a 2-y follow-up study. Int J Obes 2003; 27: 1233–41.

Le Pen C, Levy E, Loos F et al. “Specific” scale compared with “generic” scale: a double measurement of the quality of life in a French community sample of obese subjects. J Epidemiol Community Health 1998; 52: 445–50.

Skalska H, Sobotik Z, Jezberova D et al. Use and evaluation of the Czech version of the SF-36 questionnaire self-reported health status of medical students. Cent Eur J Public Health 2000; 8: 88–93.

Surtees PG, Wainwright NW, Khaw KT. Obesity, confidant support and functional health: cross-sectional evidence from the EPIC-Norfolk cohort. Int J Obes 2004; 28: 748–58.

Yancy WS, Jr., Olsen MK, Westman EC et al. Relationship between obesity and health-related quality of life in men. Obes Res 2002; 10: 1057–64.

Dalle Grave R, Todesco T, Banderali A et al. Cognitivebehavioural guided self-help for obesity: a preliminary research. Eat Weight Disord 2004; 9: 69–76.

Kaukua J, Pekkarinen T, Sane T et al. Health-related quality of life in WHO class II-III obese men losing weight with very-low-energy diet and behaviour modification: a randomised clinical trial. Int J Obes 2002; 26: 487–95.

Patrick DL, Bushnell DM, Rothman M. Performance of two self-report measures for evaluating obesity and weight loss. Obes Res 2004; 12: 48–57.

Rippe JM, Price JM, Hess SA et al. Improved psychological well-being, quality of life, and health practices in moderately overweight women participating in a 12-week structured weight loss program. Obes Res 1998; 6: 208–18.

Chaput JP, Drapeau V, Hetherington M et al. Psychobiological impact of a progressive weight loss program in obese men. Physiol Behav 2005; 86: 224–32.

Fontaine KR, Barofsky I, Andersen RE et al. Impact of weight loss on health-related quality of life. Qual Life Res 1999; 8: 275–7.

Goulis DG, Giaglis GD, Boren SA et al. Effectiveness of home-centered care through telemedicine applications for overweight and obese patients: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Obes 2004; 28: 1391–8.

Hayward LM, Sullivan AC, Libonati JR. Group exercise reduces depression in obese women without weight loss. Percept Mot Skills 2000; 90: 204–8.

Laferrere B, Zhu S, Clarkson JR et al. Race, menopause, health-related quality of life, and psychological well-being in obese women. Obes Res 2002; 10: 1270–5.

Lee PH, Chang WY, Liou TH et al. Stage of exercise and health-related quality of life among overweight and obese adults. J Adv Nurs 2006; 53: 295–303.

Marchesini G, Solaroli E, Baraldi L et al. Health-related quality of life in obesity: the role of eating behaviour. Diabetes Nutr Metab 2000; 13: 156–64.

Marchesini G, Natale S, Chierici S et al. Effects of cognitive-behavioural therapy on health-related quality of life in obese subjects with and without binge eating disorder. Int J Obes 2002; 26: 1261–7.

Marchesini G, Bellini M, Natale S et al. Psychiatric distress and health-related quality of life in obesity. Diabetes Nutr Metab 2003; 16: 145–54.

Masheb RM, Grilo CM. Quality of life in patients with binge eating disorder. Eat Weight Disord 2004; 9: 194–9.

Ni Mhurchu C, Bennett D, Lin R et al. Obesity and health-related quality of life: results from a weight loss trial. NZ Med J 2004; 117: U1211.

Samsa GP, Kolotkin RL, Williams GR et al. Effect of moderate weight loss on health-related quality of life: an analysis of combined data from 4 randomized trials of sibutramine vs placebo. Am J Manag Care 2001; 7: 875–83.

Teixeira PJ, Going SB, Houtkooper LB et al. Weight loss readiness in middle-aged women: psychosocial predictors of success for behavioral weight reduction. J Behav Med 2002; 25: 499–523.

Wamsteker E, Geenen R, Iestra J et al. Beleving van obesitas. Gewichtsverlies en de kwaliteit van leven na een dieetbehandeling met maaltijdvervangers (The experience of obesity. Weight loss and quality of life after a low-caloric diet consisting of meal replacements.). Ned Tijdschr Diëtisten 2003; 58: 59–63.

Ahroni JH, Montgomery KF, Watkins BM. Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding: weight loss, co-morbidities, medication usage and quality of life at one year. Obes Surg 2005; 15: 641–7.

Choban PS, Onyejekwe J, Burge JC et al. A health status assessment of the impact of weight loss following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for clinically severe obesity. J Am Col Surg 1999; 188: 491–7.

Dixon JB, Dixon ME, O’Brien PE. Quality of life after Lapband placement: influence of time, weight loss, and comorbidities. Obes Res 2001; 9: 713–21.

Dymek MP, le Grange D, Neven K et al. Quality of life and psychosocial adjustment in patients after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a brief report. Obes Surg 2001; 11: 32–9.

Fabricatore AN, Wadden TA, Sarwer DB et al. Health-related quality of life and symptoms of depression in extremely obese persons seeking bariatric surgery. Obes Surg 2005; 15: 304–9.

Horchner R, Tuinebreijer MW, Kelder PH. Quality-of-life assessment of morbidly obese patients who have undergone a Lap-Band operation: 2-year follow-up study. Is the MOS SF-36 a useful instrument to measure quality of life in morbidly obese patients? Obes Surg 2001; 11: 212–8; discussion 9.

Horchner R, Tuinebreijer W. Improvement of physical functioning of morbidly obese patients who have undergone a Lap-Band operation: one-year study. Obes Surg 1999; 9: 399–402.

Larsen JK, Geenen R, van Ramshorst B et al. Psychosocial functioning before and after laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding: a cross-sectional study. Obes Surg 2003; 13: 629–36.

Malone M, Alger-Mayer S. Binge status and quality of life after gastric bypass surgery: a one-year study. Obes Res 2004; 12: 473–81.

Nguyen NT, Goldman C, Rosenquist CJ et al. Laparoscopic versus open gastric bypass: a randomized study of outcomes, quality of life, and costs. Ann Surg 2001; 234: 279–89; discussion 89–91.

Nickel C, Widermann C, Harms D et al. Patients with extreme obesity: change in mental symptoms three years after gastric banding. Int J Psychiatry Med 2005; 35: 109–22.

O’Brien PE, Dixon JB, Laurie C et al. A prospective randomized trial of placement of the laparoscopic adjustable gastric band: comparison of the perigastric and pars flaccida pathways. Obes Surg 2005; 15: 820–6.

Ohrstrom M, Hedenbro J, Ekelund M. Energy expenditure during treadmill walking before and after vertical banded gastroplasty: a one-year follow-up study in 11 obese women. Eur J Surg 2001; 167: 845–50.

Van Hout GC, Van Oudheusden I, Krasuska AT et al. Psychological profile of candidates for vertical banded gastroplasty. Obes Surg 2006; 16: 67–74.

Mokdad AH, Ford ES, Bowman BA et al. Prevalence of obesity, diabetes, and obesity-related health risk factors, 2001. JAMA 2003; 289: 76–9.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

The following supplementary material is available for this article from the corresponding author ( a.van.nunen@onsneteindhoven.nl ) and from www.obesitystudies.nl

Table A1. Characteristics and weighted means on the IWQOL-Lite quality of life questionnaire for four populations before treatment.

Table A2. Characteristics and weighted means on the SF-36 quality of life questionnaire for four populations before treatment.

Figure A1. Flow diagram of the search strategy leading to the 54 articles included in the meta-analysis.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0 ), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

van Nunen, A.M.A., Wouters, E.J.M., Vingerhoets, A.J.J.M. et al. The Health-Related Quality of Life of Obese Persons Seeking or Not Seeking Surgical or Non-surgical Treatment: a Meta-analysis. OBES SURG 17, 1357–1366 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-007-9241-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-007-9241-9