Abstract

Pay-for-performance (P4P) has become a prominent component of health care funding in the Affordable Care Act (ACA) era. Although the ACA’s future remains unclear, these programs receive bipartisan support and will likely continue to be a part of payment policies. At the same time, racial and class disparities remain among the most pressing of the many challenges facing the US health system. We review evidence of the effects of P4P on disparities at the population and individual levels. Providers caring for predominantly minority patients or those with lower socioeconomic status are known to have poorer quality metrics. Financial penalties run the risk of exacerbating disparities along race and class lines and across hospitals. The evidence regarding P4P programs is mixed, with safety-net hospitals facing greater penalties but with some improvement in outcomes among minority patients. A better understanding of the longitudinal effects of these plans is needed, and policymakers should be conscious of the risks in expanding these programs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Pay-for-performance (P4P) programs have the potential to improve quality of care and reduce costs. Health care providers are incentivized through compensation to provide better-quality care based on outcome and/or process measures. With rising health care costs and poorer health outcomes in the US than in other countries, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) expanded the use of P4P in Medicare programs as a means of achieving better quality and value. The ACA created a number of alternative payment models (APMs), with a focus on value in health care delivery through accountable care organizations (ACOs). The passage of the Medicare and Children’s Health Insurance Reauthorization Program (MACRA) deepened the federal government’s commitment to APMs. Although aspects of these policies might change in the coming years, the concept of pay-for-performance has historically received bipartisan support.

In this context, it is important to understand the impact of P4P on health care disparities. Research has clearly shown that lower socioeconomic status (SES) and minority race are associated with worse health outcomes, less access to care, and lower life expectancy.1,2 The conceptual goal of P4P and APMs is to incentivize value through rewarding higher-quality care at lower cost. However, even if P4P is effective in improving value, whether P4P improves quality for all groups of patients remains unclear. As health care disparities remain one of our country’s major health challenges, it is crucial that policymakers monitor the impact of these policies on populations already with poorer health outcomes. P4P could exacerbate disparities, improve quality for all groups equally, or even attenuate disparities.

There are several conceptual reasons to be concerned that P4P and value-based programs might worsen health disparities. First, providers in underserved areas already suffer from poorer outcomes and process measures. Programs that apply punitive financial measures to these hospitals could worsen the lack of resources in underserved areas.

Second, P4P programs choose specific quality metrics over others. Focusing attention on some quality metrics may sacrifice attention to other aspects of quality. As such, the care for those patients could suffer. For example, efforts targeting certain diseases (HIV, substance use disorders, mental health disorders) may be more relevant to vulnerable patients than metrics such as hospital-acquired infections, time to acute myocardial infarction treatment, or readmission rates.

Third, in populations with a smaller proportion of minority, low-income, or sicker patients, providers might choose to avoid underserved patients. The patients known to be associated with poorer health outcomes might very well be from predominantly minority or low-SES groups.

EVIDENCE OF POOR QUALITY IN MINORITY AND LOW-INCOME POPULATIONS

Minority and poorer populations are associated with providers with poorer quality metrics. Hospitals that serve a greater proportion of poor, black, and Hispanic patients are associated with worse outcomes and rates of safety events.3,4 Hospitals that care for a disproportionate black population have demonstrated worse outcomes than other hospitals for both their black and white Medicare beneficiaries.5 Black patients are significantly more likely to be readmitted to the hospital after major surgery, but they also have lower 30-day adjusted mortality and higher-rated patient experiences.6 In terms of quality improvement, hospitals with a larger Medicaid population have demonstrated poorer performance in measures for acute myocardial infarction and heart failure.7 In addition, safety-net hospitals tended to have smaller gains in quality performance over 3 years and were less likely to be high-performing than non-safety-net hospitals.8

OUTCOMES OF CURRENT P4P AND VALUE-BASED PROGRAMS

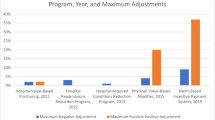

VBP/HRRP

Medicare’s Value-Based Purchasing (VBP) Program and Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP) are two of the most recent P4P programs introduced by the Centers for Medicare &Medicaid Services (CMS). Safety-net hospitals have been more likely to incur financial penalties in these programs than other hospitals. In California, despite having lower 30-day adjusted mortality, safety-net hospitals were more likely to incur financial penalties than non-safety net hospitals.9 This issue likely points to the question of risk adjustment when considering quality metrics across populations. When adjusting performance measures for SES, the proportion of safety-net hospitals penalized in HRRP programs dropped by 10%.10 Although safety-net hospitals bore a larger burden of penalties, they were able to improve 30-day readmissions and reduce readmission rate disparities relative to non-safety-net hospitals.11 In this setting, financially weakening resource-poor institutions could reduce their ability to attract caregivers or to invest in care delivery, ultimately perpetuating disparities.

ACO

ACOs focus on value through cost reduction coupled with accountability for quality. While much of the Medicare ACO data has yet to be analyzed in terms of disparities, ACO physician participation is lower in areas that are predominantly black or poor.12 A recent national survey of ACOs found that those serving more minority patients were associated with worse scores on 23 of 25 quality measures. ACOs will face the same challenges as any P4P program, dealing with the same issues of already poorer quality in low-income and minority populations.13 This race- and income-based differential access to the care coordination provided by ACOs with better resources could potentially exacerbate disparities in certain parts of the country. In a private insurance ACO, a greater increase in process measures was found among low-income versus higher-income groups, with no significant difference in outcome measures.14 additional data would be helpful for understanding the effects of ACOs on disparities.

CONCLUSION

As efforts continue toward developing optimal P4P arrangements, several controversies remain. There is uncertainty regarding how best to risk-adjust for providers that serve more low-income and minority patients. While many argue that adjusting for social risk is necessary, there is concern that adjustments will lower quality standards. The US Department of Health & Human Services (HHS) recently released recommendations that encourage the identification of metrics specific to social risk that will prevent inequitable penalties, while maintaining high targets for improvement.15 Overall, evidence to support substantive conclusions regarding the largest and most recent P4P programs and their effects on disparities is largely mixed and still inadequate. The evidence we do have suggests that these programs at least have the potential to reduce disparities, but their effects vary widely, and further investigation is necessary. There may be a more dynamic effect of P4P on providers over an extended period of time, as initial financial losses incurred from penalties could ultimately stimulate more lasting change. However, such longitudinal effects have yet to be determined.

Moving forward, longitudinal studies on the VBP, HRRP, and ACO programs would help provide a greater understanding of how and why outcomes differ across race/ethnicity and SES over time. Both intra- and inter-hospital disparities should be analyzed to determine how these interventions and incentives affect practices in the same setting and across settings. Analysis of quality metrics should seek to identify those metrics that are most challenging among disadvantaged populations. The long-term effects of annual penalties are not yet known, and will be important for the sustainability of these programs. Additional work is also needed to examine variation in performance among provider groups with similar patient populations.

The current uncertain federal health policy environment notwithstanding, P4P approaches are likely here to stay. Hopefully, programs meant to increase quality will also increase equity. Equity itself could be incorporated into performance metrics associated with P4P, with potential rewards for reducing disparity in a population. Furthermore, as P4P expands, research exploring the relative effects of policies on disadvantaged populations will be essential. As the evidence base grows, policymakers and researchers must work together to ensure that these new programs are not harmful to the most disadvantaged within our health system.

References

Braveman PA, Cubbin C, Egerter S, Williams DR, Pamuk E. Socioeconomic disparities in health in the United States: what the patterns tell us. Am J Public Health. 2010; 100 (Suppl 1):S186–96.

Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, the Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care, Institute of Medicine. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2003.

Ly DP, Lopez L, Isaac T, Jha AK. How do black-serving hospital perform on patient safety indicators? Implications for national public reporting and pay-for-performance? Med Care. 2010;48(12) 1133–7.

Jha AK, Orav EJ, Zheng J, Epstein AM. The characteristics and performance of hospitals that care for elderly Hispanic Americans. Health Aff (Project Hope). 2008;27(2):528–37.

Jha AK, Epstein AM. Governance around quality of care at hospitals that disproportionately care for black patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(3):297–303.

Tsai TC, Orav EJ, Joynt KE. Disparities in surgical 30-day readmission rates for Medicare beneficiaries by race and site of care. Ann Surg. 2014;259(6):1086–90.

Werner RM. Comparison of Change in Quality of Care Between Safety-Net and Non–Safety-Net Hospitals. JAMA. 2008;299(18):2180

Gilman M, Hockenberry JM, Adams EK, Milstein AS, Wilson IB, Becker ER. The Financial Effect of Value-Based Purchasing and the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program on Safety-Net Hospitals in 2014: A Cohort Study. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(6):427–36.

Gilman M, Adams EK, Hockenberry JM, Wilson IB, Milstein AS, Becker ER. California safety-net hospitals likely to be penalized by ACA value, readmission, and meaningful-use programs. Health Aff (Project Hope). 2014;33(8):1314–22.

Glance LG, Kellermann AL, Osler TM, Li Y, Li W, Dick AW. Impact of Risk Adjustment for Socioeconomic Status on Risk-adjusted Surgical Readmission Rates. Ann Surg. 2016;263(4):698–704.

Carey K, Lin MY. Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program: Safety-Net Hospitals Show Improvement, Modifications To Penalty Formula Still Needed. Health Aff (Project Hope). 2016;35(10):1918–1923.

Yasaitis LC, Pajerowski W, Polsky D, Werner RM. Physicians’ Participation In ACOs Is Lower In Places With Vulnerable Populations Than In More Affluent Communities. Health Aff (Project Hope). 2016;35(8):1382–90.

Lewis VA, Fraze T, Fisher ES, Shortell SM, Colla CH. ACOs Serving High Proportions Of Racial And Ethnic Minorities Lag In Quality Performance. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(1): 57–66.

Song Z, Rose S, Chernew ME, Safran DG. Lower-Versus Higher-Income Populations In The Alternative Quality Contract: Improved Quality And Similar Spending. Health Aff (Project Hope). 2017;36(1)74–82

Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary of Planning and Evaluation. Report to Congress: social risk factors and performance under Medicare’s value-based payment programs. https://aspe.hhs.gov/pdf-report/report-congress-social-risk-factors-and-performance-under-medicares-value-based-purchasing-programs. Accessed: July 10, 2017.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Jason H. Wasfy is the recipient of a KL2 TR001100 Career Development Award funded in the area of health disparities research. All other authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shakir, M., Armstrong, K. & Wasfy, J.H. Could Pay-for-Performance Worsen Health Disparities?. J GEN INTERN MED 33, 567–569 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4243-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4243-3