Abstract

Background

The growing movement toward more accountable care delivery and the increasing number of people with chronic illnesses underscores the need for primary care practices to engage patients in their own care.

Objective

For adult primary care practices seeing patients with diabetes and/or cardiovascular disease, we examined the relationship between selected practice characteristics, patient engagement, and patient-reported outcomes of care.

Design

Cross-sectional multilevel observational study of 16 randomly selected practices in two large accountable care organizations (ACOs).

Participants

Patients with diabetes and/or cardiovascular disease (CVD) who met study eligibility criteria (n = 4368) and received care in 2014 were randomly selected to complete a patient activation and PRO survey (51% response rate; n = 2176). Primary care team members of the 16 practices completed surveys that assessed practice culture, relational coordination, and teamwork (86% response rate; n = 411).

Main Measures

Patient-reported outcomes included depression (PHQ-4), physical functioning (PROMIS SF12a), and social functioning (PROMIS SF8a), the Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care instrument (PACIC-11), and the Patient Activation Measure instrument (PAM-13). Patient-level covariates included patient age, gender, education, insurance coverage, limited English language proficiency, blood pressure, HbA1c, LDL-cholesterol, and disease comorbidity burden. For each of the 16 practices, patient-centered culture and the degree of relational coordination among team members were measured using a clinician and staff survey. The implementation of shared decision-making activities in each practice was assessed using an operational leader survey.

Key Results

Having a patient-centered culture was positively associated with fewer depression symptoms (odds ratio [OR] = 1.51; confidence interval [CI] 1.04, 2.19) and better physical function scores (OR = 1.85; CI 1.25, 2.73). Patient activation was positively associated with fewer depression symptoms (OR = 2.26; CI 1.79, 2.86), better physical health (OR = 2.56; CI 2.00, 3.27), and better social health functioning (OR = 4.12; CI 3.21, 5.29). Patient activation (PAM-13) mediated the positive association between patients’ experience of chronic illness care and each of the three patient-reported outcome measures—fewer depression symptoms, better physical health, and better social health. Relational coordination and shared decision-making activities reported by practices were not significantly associated with higher patient-reported outcome scores.

Conclusions

Diabetic and CVD patients who received care from ACO-affiliated practices with more developed patient-centered cultures reported lower PHQ-4 depression symptom scores and better physical functioning. Diabetic and CVD patients who were more highly activated to participate in their care reported lower PHQ-4 scores and better physical and social outcomes of care.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Forty-six million Americans have diagnosed cardiovascular disease (CVD), diabetes, or both, representing a combined annual healthcare cost of $354 billion.1 – 3 It is increasingly recognized that greater efforts to engage patients in their care are needed to improve outcomes for these populations.4 – 9 While there is a growing body of literature on patient engagement and patient-reported outcomes of care,10 – 13 little is known about what practices can do to encourage greater patient engagement and how such engagement might be associated with better patient-reported outcomes of care.14 – 16

To address this gap in knowledge, we studied 16 primary care practices belonging to two large ACOs that implemented a variety of patient engagement initiatives for patients with cardiovascular disease (CVD), diabetes, or both. We hypothesized that patients receiving care from practices that made greater efforts to engage them, that were more patient-centered, that better coordinated their work with one another, and for which patients reported better experiences in receiving care would be associated with higher patient-reported outcomes of care. We also hypothesized that the relationship between patient experience of care and patient-reported outcomes would be mediated by the degree of patient activation.

METHODS

Study Design and Data Sources

We had the opportunity to study naturally occurring differences in the rate of implementation of patient engagement initiatives in two large ACOs—Advocate Health Care (AHC) in Chicago, IL, and DaVita HealthCare Partners (DHCP) in Los Angeles, CA. Key background characteristics of the two ACOs are shown in Table 1. Each is a large and long-established healthcare organization participating in the Medicare Shared Savings Program and in other risk-bearing contracts that create incentives to increase patient involvement in their care in order to achieve better outcomes and to reduce the costs associated with emergency department visits and preventable hospital admissions and re-admissions.

Based on the existing literature, we developed a baseline survey of 39 patient activation and engagement activities (available online, Appendix 1). The survey was completed by a clinical or operational leader from each of the 44 AHC and 27 DHCP practices. Practices were scored based on their responses to the 39-item instrument indicating the extent of implementation of each activity within their practice. From each ACO, we randomly sampled four practices from the top quartile and four from the bottom quartile of the score distribution in order to maximize the baseline variance in patient activation and engagement activities of the study sites. This yielded a total of 16 practices for analysis—eight scoring in the highest quartile and eight in the lowest quartile of implementation of patient engagement activities (see Table 2 for descriptive characteristics of the 16 practice sites). The eight from the highest quartile scored an average of 79.1 (range 71.8–100) of the 100 possible points for each of the questions on the baseline survey, and those in the lowest quartile scored an average of 30.6 (range 5.1–42.0) out of the 100 possible points for each question.

We based sample size power calculations on the detection of clinically meaningful changes in PROMIS physical function scores17 and on blood pressure, assuming a 50% rate of response to the patient survey. This resulted in sampling 273 adult patients with CVD and/or diabetes who had at least one visit in 2014 from each practice using the inclusion criteria shown in Table 3. From the electronic health record we collected data on blood pressure, glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol levels, comorbid conditions, sociodemographic characteristics, and insurance status on each patient. We collected data on patient-reported outcomes of care (PROs), patient assessment of the chronic illness care that they received (PACIC), and patient-reported activation and engagement (PAM) from a mailed survey administered in both English and Spanish, as needed, with telephone follow-up, obtaining a 51% completion rate (n = 2176). We also collected survey data from adult primary care team members at each of the 16 practices regarding the extent to which the practice exhibited a patient-centered culture and the degree of relational coordination existing among the people occupying different roles on the team, including primary care physicians, nurses, medical assistants, diabetic nurse educators, nutritionists, and receptionists.18 , 19 We obtained an overall 86% response rate from the team members (n = 411). The study was approved by the institutional review board (IRB) of the University of California, Berkeley, prior to data collection.

Patient-Reported Outcomes

PROs included the validated 12-item Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Physical Function form (Short Form 12a), the validated eight-item PROMIS Social Function form (Short Form 8a), and the validated four-item Patient Health Questionnaire for Depression and Anxiety (PHQ-4) emotional health screening tools17 , 20 , 21 (available online, Appendix 2). The Cronbach alpha internal consistency reliability coefficients were 0.92, 0.95, and 0.87, respectively.22

Practice-Level Independent Variables

Practice-reported patient engagement in decision-making activities was measured by a seven-item subscale (α = 0.89) based on factor analysis of the 39-item baseline survey. The items included in the subscale were as follows: “clinicians encourage patients to discuss their work, home life, and social situation”; “staff note patient preferences for treatment in the patient’s record”; “clinicians consistently involve patients in developing treatment goals”; “physicians have follow-up discussions with patients regarding their treatment options and preferences”; “ clinicians discuss the importance of patient advance directives”; “clinicians discuss the hospice care options with patients”; and “clinicians discuss the availability of hospital-based and community-based palliative care”. The response categories included the following: “Yes, fully implemented”; “Yes, partially implemented”; “Yes, but not regularly”; and “No”. This measure was calculated as a continuous score from 0 to 7. We hypothesized that the efforts of practices to better engage patients would be positively associated with better patient-reported outcomes of care through the increased motivation and participation of patients in achieving treatment goals.6 , 16

Patient centeredness was measured by a five-item scale (α = 0.92) used in previous research,23 composed of each team member’s degree of agreement with the following statements: 1) the practice does a good job of assessing current patient needs and expectations; 2) staff promptly resolve patient complaints; 3) patients’ complaints are studied to identify patterns and to prevent the same problems from recurring; 4) the organization uses data from patients to improve services; and 5) the organization uses data on customer expectations and/or satisfaction/experiences when designing new services (available online, Appendix 4). We hypothesized that these types of patient-responsive practice behaviors would be associated with better patient-reported outcomes of care given that existing research has found them to be positively associated with greater use of evidence-based care management processes.23

The seven-item between-role relational coordination measure α = 0.87 used in previous research18 , 19 , 24 , 25 asked each team member to assess the frequency, timeliness, accuracy, and problem-solving focus of communication with each other team member with whom they interacted, in addition to the degree of shared goals, shared knowledge, and mutual respect among team members (available online, Appendix 3). For example, each team member was asked, “How frequently do people in each of these groups communicate with you about patients with diabetes and/or cardiovascular disease?” With regard to shared knowledge, each team member was asked, “Do people in each of these groups know about the work you do with patients with diabetes and/or cardiovascular disease?” For purposes of these analyses, we restricted the role relationships to those involving the patient’s primary care physician, the nurse, and the medical assistant, as they most frequently interacted with each other and with the patient. Based on existing research, we hypothesized that greater within-group relational coordination would be positively associated with better patient-reported outcomes.17 , 18

Patient-Reported Independent Variables

Patients’ perceptions of their chronic illness care were assessed by the 11-item Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (PACIC) scale used in previous research26 – 28 (α = 0.93). Sample items included the following: “Over the past six months, when I received care for my chronic condition, how often was I: given choices about treatments to think about; helped to set specific goals to improve my eating or exercise; and helped to plan ahead so I could take care of my condition even in hard times”. Response categories included “never”, “sometimes”, “usually”, and “always”. We hypothesized that patients who reported that they were more satisfied with their chronic illness care would report better patient-reported outcomes.27

We measured patient activation using the 13-item Patient Activation Measure (PAM) developed by Hibbard et al.29 (α = 0.90). Sample questions completed by all surveyed patients included “When all is said and done, I am the person who is responsible for managing my health condition;” “I am confident that I can take actions that will help prevent or minimize some symptoms or problems associated with my health condition” and “I am confident that I can follow through on medical treatments I need to do at home”. Response categories were “strongly disagree”, “disagree”, “agree”, and “strongly agree”. The PAM has been associated with positive health behaviors such as aerobic exercise and receiving preventive cancer screenings as well as more favorable emotional health and lower costs of care.6 , 16 , 30 In addition to a continuous measure, the response scores were summarized into four quartiles representing different categories of activation levels. An individual in the lowest level is a passive participant in healthcare decisions. An individual in the second level of activation has the knowledge and confidence to take a more active role in their healthcare, but has not yet done so. In the third level of activation, the patient plays an active role in making healthcare decisions with their providers. In the highest level of activation, the patient has the knowledge and confidence to take action concerning their own healthcare, even during times of stress.30 Extending previous research noted above, we hypothesized that PAM would be positively associated with PROs of physical function, social function, and depression symptoms, and would largely mediate the positive association of better patient experiences of chronic care and better patient-reported outcomes of care.

Control Variables

From the electronic health record, we collected data on the presence or absence of up to 13 co-morbid medical conditions, including other forms of heart failure, atherosclerosis, aortic aneurysm, aortocoronary bypass, hypertension, asthma, emphysema, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), mood disorders, other nonorganic psychoses, anxiety, adjustment reaction, and depression.

We controlled for the patient’s latest reported blood pressure <140/90 mmHg; LDL-C ≤ 100 mg/dl, and HbA1c ≤8.0%. We also adjusted for patient age, sex, education, insurance status, and limited English language proficiency.

Statistical Methods

To account for the clustering of patients within the 16 practices, we used hierarchical linear models (HLM), with patients as the first-level analysis and practices as the second level31 to estimate the association between predictors and each PRO. Given the relative skewness of the PROs toward more positive outcomes, and for ease of interpretation, we report logistic regression results dichotomizing patients’ scores above or below the median on each of the PHQ-4 depression symptom, physical, and social outcome measures. For these analyses, the results are reported as odds ratios (ORs). We also estimated multilevel linear regression models using continuous PRO measures, and obtained nearly identical results (data not shown). We tested for the mediating effect of PAM on each of the patient-reported PHQ-4 depression, physical, and social outcomes by running multilevel mediation tests32 to estimate the direct and indirect effect of PAM on PROs.

We conducted a number of sensitivity analyses involving different measures of disease burden, including 2+ comorbid conditions, 3+ comorbid conditions, and whether the patient had one or more mental health conditions or at least one physical plus at least one mental health condition.33 – 36 We also examined the effect of including a broader number of patient care team roles in the measure of relational coordination, including diabetes nurse educators, social workers, and receptionists. We tested for a number of potential moderating interaction effects involving disease burden and the PAM to see whether the effects might be greatest for the sickest patients. We also tested for an interaction effect of patient-reported shared decision-making and PAM to see whether shared decision-making mattered most for patients who were very highly activated or were very disengaged. The intraclass correlation coefficient in all models supported model assumptions (p < 0.001). We analyzed the data using Stata language 14.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX) and considered the regression coefficients significant at a level of ≤ 0.05.

RESULTS

Table 4 shows the descriptive statistics for key study variables. Tables 5 and 6 show the logistic regression results with and without the PAM included, respectively. The intraclass correlation coefficient (p < 0.001) supported model assumptions. As indicated in Table 5, patients receiving care from teams with more developed patient-centered cultures were significantly more likely to score above the median on the PHQ-4 on having fewer depression symptoms (OR 1.56; 1.08–2.25 CI) and above the median on better physical health scores (OR 1.85; 1.27–2.72 CI). Also, patients reporting better assessment of their chronic illness care were significantly more likely to score above the median on the PHQ-4 reporting fewer depression symptoms (OR 1.24; 1.11–1.38 CI), and to have above-median physical health scores (OR 1.26; 1.12–1.41 CI) and above-median social health scores (OR 1.26; 1.13–1.40 CI). Relational coordination was not significantly associated with patient-reported outcomes, while practice site reporting efforts to engage patients was slightly negatively associated with the PHQ-4 depression symptoms (OR 0.96; 0.92–0.99 CI), and physical (OR 0.95; 0.91–0.99 CI) and social (OR 0.96; 0.92–0.99 CI) patient-reported outcomes.

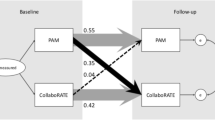

As shown in Table 6, the association of patients’ perception of their chronic illness care was mediated by patient activation, with more highly activated patients more than twice as likely to score above the median on having fewer PHQ-4 depression symptoms (OR 2.26; 1.79–2.86 CI) and having above-median better physical health scores (OR 2.56; 2.00–3.27 CI), and more than four times as likely to be above the median (OR 4.12; 3.21–5.29 CI) on the measure of social health. The formal mediation tests indicated that all association of patients’ perception of their chronic illness care was mediated by the PAM (all p < 0.0001).32 Patients receiving care from more patient-centered teams continued to be significantly more likely to be above the median in being less depressed (OR 1.51; 1.04–2.19 CI) and have above-median better physical health scores (OR 1.85; 1.24–2.73 CI).

When adjusting for diagnosed mental health conditions instead of overall disease burden, we found nearly identical results to those reported above, with the association between patients’ perception of their chronic illness care and patient-reported outcomes being entirely mediated by the PAM (data not shown).

Among the control variables, women reported lower outcome scores than men; those with a post-baccalaureate degree reported higher outcome scores than those with less education, and those with greater disease burden experienced lower outcome scores. Limited English language proficiency had no significant relationship with any of the outcome scores. Diabetic and CVD patients aged 65 and older reported significantly lower depression scores, consistent with national data indicating that those over age 65 report being in better mental health than other age groups.37

Additional sensitivity analyses (not shown) did not change the main results reported in Tables 5 and 6. None of the interaction effects were statistically significant. In other analyses (not shown), we also controlled for blood pressure, HbA1c, and LDL levels, and found no associations between these intermediate outcomes and any of the PROs.

DISCUSSION

As hypothesized, patients receiving care from practices with a more patient-centered culture as reported by primary care team members were less likely to report depression symptoms and more likely to report better physical health outcomes. It is important to note that the patient-centered culture measure is based on primary care team members who have direct daily contact with patients. This is in contrast to the high-level aggregated 39-item measure reported by the practice administrator, which was found to be slightly negatively associated with patient-reported outcomes. The implication of this seeming contradiction for clinical leaders is to focus improvement efforts on a culture that actively uses patient data and feedback to meet patient needs and expectations. The cultural dimension may be more important than simply increasing the number of activities the practice uses in patient engagement efforts. This finding holds true even when patient activation levels are taken into account.

Also, as hypothesized, patients’ experiences of chronic illness care were positively associated with fewer depression symptoms and better physical and social functioning. As predicted, and consistent with a recent Australian study,38 these associations were mediated by more highly activated and engaged patients. The relationships among patient chronic illness care experiences, the PAM, and patient-reported outcomes of care suggest that actions or interventions to better engage patients may have a dual benefit. More engaged patients rate the care they receive more highly and they report better outcomes of care. This may be because more highly activated, engaged patients ask more questions to have their concerns addressed and, as a result, are more satisfied with their care experience and more motived to achieve desired outcomes.

Contrary to the hypothesized relationship, greater coordination among team members was not associated with better patient-reported outcomes. Including patient reports of relational coordination among team members in future research may yield different results.39 – 41

Limitations

These findings should be considered within the context of certain limitations. There were relatively small but, due to the large sample size, statistically significant differences between respondents and non-respondents to the patient survey for a few sociodemographic characteristics. The response percentage was higher among female than male patients (54.7% vs. 49.0%, p < 0.0001) and among those 65 years of age or older than under age 65 (53.8% vs. 46.2%, p < 0.0001), and those with only diabetes or only CVD had somewhat lower response rates (49.12% and 47.69%, respectively) than those with both diabetes and CVD (56.53%; p = 0.0002).

Since the findings are based on cross-sectional data, we cannot conclude that having a more patient-centered practice culture will result in better patient-reported outcomes of care, or that having more highly activated patients will automatically result in better patient-reported outcomes of care. Longitudinal studies are needed to build on these analyses. Where feasible, randomized controlled trials of specific practice culture interventions and/or specific patient activation interventions can extend the current analysis.

Finally, our findings cannot be generalized to the larger population of patients receiving care from ACO primary care practices across the country, particularly those serving a higher percentage of safety-net and Medicaid patients, given that the results are based on just two non-randomly selected ACOs who were specifically interested in the research collaboration.

CONCLUSION

Overall, the findings suggest the importance of having a patient-centered culture that enables primary care team members to actively engage their patients in care that is associated with achieving outcomes important to patients.42 The importance and use of patient-reported outcome measures is likely to grow with their inclusion as quality measures in the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA) legislation that, by 2019, will reward physicians who choose to practice in ACO-like arrangements with a 5% bonus, or they can remain on a fee schedule with a smaller percentage increase in compensation for achieving predetermined cost and quality metrics.43 Private sector value-based payment arrangements incorporating patient-reported outcome measures are also emerging.44

There are a number of challenges to incorporating the use of patient-reported outcome measures into everyday practice, including how best to integrate them into the electronic health record and the overall flow of clinical work, how to most efficiently collect the information from patients, and how to decide when the information obtained is likely to alter treatment or provide useful insights for focusing on patients that may require greater attention.45 – 48 Nevertheless, a number of organizations are successfully addressing these challenges.49 Aggregated across patients over time, patient-reported outcomes can also provide an important baseline for conducting population-based research, working toward achieving improvements in overall population health.

References

American Diabetes Association. Data from the 2011 national diabetes fact sheet 2013 [accessed 2016, December 22]. Available from: http://www.diabetes.org/diabetes-basics/diabetes-statistics/.

Heidenreich PA, Trogdon JG, Khavjou OA, Butler J, Dracup K, Ezekowitz MD, et al. Forecasting the future of cardiovascular disease in the United States: a policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123(8):933–44.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Fact Sheet, 2011. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2011.

Coleman K, Austin BT, Brach C, Wagner EH. Evidence on the chronic care model in the new millennium. Health Aff (Millwood). 2009;28(1):75–85. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.28.1.75.

Lin GA, Halley M, Rendle KA, Tietbohl C, May SG, Trujillo L, et al. An effort to spread decision aids in five California primary care practices yielded low distribution, highlighting hurdles. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(2):311–20.

Hibbard JH, Mahoney ER, Stock R, Tusler M. Do increases in patient activation result in improved self-management behaviors? Health Serv Res. 2007;42(4):1443–63.

Hibbard JH, Stockard J, Mahoney ER, Tusler M. Development of the patient activation measure (PAM): Conceptualizing and measuring activation in patients and consumers. Health Serv Res. 2004;39(4):1005–26.

Mosen DM, Schmittdiel J, Hibbard J, Sobel D, Remmers C, Bellows J. Is patient activation associated with outcomes of care for adults with chronic conditions? J Ambulatory Care Manage. 2007;30(1):21–9.

Delbanco T, Walker J, Bell SK, Darer JD, Elmore JG, Farag N, et al. Inviting patients to read their doctors’ notes: a quasi-experimental study and a look ahead. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(7):461–70. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-157-7-201210020-00002.

Juul L, Maindal HT, Zoffmann V, Frydenberg M, Sandbaek A. A cluster randomised pragmatic trial applying self-determination theory to type 2 diabetes care in general practice. BMC Fam Pract. 2011;12:130. doi:10.1186/1471-2296-12-130.

Zoffmann V, Kirkevold M. Realizing empowerment in difficult diabetes care: a guided self-determination intervention. Qual Health Res. 2012;22(1):103–18. doi:10.1177/1049732311420735.

Williams GC, Lynch M, Glasgow RE. Computer-assisted intervention improves patient-centered diabetes care by increasing autonomy support. Health Psychol. 2007;26(6):728–34. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.26.6.728.

Gagliardi AR, Legare F, Brouwers MC, Webster F, Badley E, Straus S. Patient-mediated knowledge translation (pkt) interventions for clinical encounters: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2016;11:26. doi:10.1186/s13012-016-0389-3.

Health policy brief: Patient engagement. Health Aff (Millwood). February 14, 2013.

LeBlanc ES, Rosales AG, Kachroo S, Mukherjee J, Funk KL, Nichols GA. Do patient or provider characteristics impact management of diabetes? Am J Manag Care. 2015;21(9):597–606.

Rodriguez HP, Rogers WH, Marshall RE, Safran DG. Multidisciplinary primary care teams: effects on the quality of clinician-patient interactions and organizational features of care. Med Care. 2007;45(1):19–27.

Cella D, Riley W, Stone A, Rothrock N, Reeve B, Yount S, et al. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005-2008. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(11):1179–94. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.011.

Gittell JH, Fairfield KM, Bierbaum B, Head W, Jackson R, Kelly M, et al. Impact of relational coordination on quality of care, postoperative pain and functioning, and length of stay: a nine-hospital study of surgical patients. Med Care. 2000;38(8):807–19.

O’Toole TP, Cabral R, Blumen JM, Blake DA. Building high functioning clinical teams through quality improvement initiatives. Qual Prim Care. 2011;19(1):13–22.

Deutsch A, Gage B, Smith L, Kelleher C. Patient-reported outcomes in performance measurement. Washington, DC: National Quality Forum (NQF); 2012.

Rose M, Bjorner JB, Gandek B, Bruce B, Fries JF, Ware JE Jr. The promis physical function item bank was calibrated to a standardized metric and shown to improve measurement efficiency. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67(5):516–26. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.10.024.

Kaplan RM, Saccuzzo DP. Psychological testing: principles, applications, and issues. 7th ed. Brooks/Cole: Monterey, CA; 1982.

Wiley JA, Rittenhouse D, Shortell SM, Casalino L, Ramsay PP, Bibi S, et al. Managing chronic illness: Physician practices increased the use of care management and medical home processes. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015; Forthcoming.

Gittell JH, Beswick J, Goldmann D, Wallack SS. Teamwork methods for accountable care: relational coordination and TeamSTEPPS®. Health Care Manag Rev. 2015;40(2):116–25. doi:10.1097/HMR.0000000000000021.

Gittell JH, Weinberg DB, Bennett AL, Miller JA. Is the doctor in? A relational approach to job design and the coordination of work. Hum Resour Manag. 2008;47(4):729–55. doi:10.1002/hrm.20242.

Glasgow RE, Wagner EH, Schaefer J, Mahoney LD, Reid RJ, Greene SM. Development and validation of the patient assessment of chronic illness care (PACIC). Med Care. 2005;43(5):436–44.

Glasgow RE, Whitesides H, Nelson CC, King DK. Use of the Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (PACIC) with diabetic patients: relationship to patient characteristics, receipt of care, and self-management. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(11):2655–61.

Gugiu PC, Coryn C, Clark R, Kuehn A. Development and evaluation of the short version of the Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care instrument. Chronic Illness. 2009;5(4):268–76. doi:10.1177/1742395309348072.

Hibbard JH, Mahoney ER, Stockard J, Tusler M. Development and testing of a short form of the patient activation measure. Health Serv Res. 2005;40(6p1):1918–30.

Greene J, Hibbard JH, Sacks R, Overton V, Parrotta CD. When patient activation levels change, health outcomes and costs change, too. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34(3):431–7. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0452.

Bryk AS, Raudenbush SW. Hierarchical linear models: applications and data analysis methods. Newbury Park: Sage Publications; 1992.

Krull JL, MacKinnon DP. Multilevel modeling of individual and group level mediated effects. Multivar Behav Res. 2001;36(2):249–77. doi:10.1207/S15327906MBR3602_06.

Hare DL, Toukhsati SR, Johansson P, Jaarsma T. Depression and cardiovascular disease: a clinical review. Eur Heart J. 2014;35(21):1365–72. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/eht462.

Fiedorowicz JG. Depression and cardiovascular disease: an update on how course of illness may influence risk. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2014;16(10):492. doi:10.1007/s11920-014-0492-6.

Semenkovich K, Brown ME, Svrakic DM, Lustman PJ. Depression in type 2 diabetes mellitus: prevalence, impact, and treatment. Drugs. 2015;75(6):577–87. doi:10.1007/s40265-015-0347-4.

Vancampfort D, Mitchell AJ, De Hert M, Sienaert P, Probst M, Buys R, et al. Type 2 diabetes in patients with major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of prevalence estimates and predictors. Depress Anxiety. 2015;32(10):763–73. doi:10.1002/da.22387.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The state of aging and health in America 2013. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2013.

Aung E, Donald M, Williams GM, Coll JR, Doi SA. Influence of patient-assessed quality of chronic illness care and patient activation on health-related quality of life. Int J Qual Health Care. 2016. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzw023.

Weinberg DB, Lusenhop RW, Gittell JH, Kautz CM. Coordination between formal providers and informal caregivers. Health Care Manag Rev. 2007;32(2):140–9. doi:10.1097/01.HMR.0000267790.24933.4c.

Cramm JM, Nieboer AP. Relational coordination promotes quality of chronic care delivery in Dutch disease-management programs. Health Care Manag Rev. 2012;37(4):301–9. doi:10.1097/HMR.0b013e3182355ea4.

Leykum LK, Lanham HJ, Pugh JA, Parchman M, Anderson RA, Crabtree BF, et al. Manifestations and implications of uncertainty for improving healthcare systems: an analysis of observational and interventional studies grounded in complexity science. Implement Sci. 2014;9:165. doi:10.1186/s13012-014-0165-1.

Rathert C, Wyrwich MD, Boren SA. Patient-centered care and outcomes: a systematic review of the literature. Med Care Res Rev. 2013;70(4):351–79. doi:10.1177/1077558712465774.

Hahn J, Blom KB. The Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA; P.L. 114-10). Congressional Research Service, 2015 Nov 10, 2015.

Weldring T, Smith SM. Patient-reported outcomes (pros) and patient-reported outcome measures (proms). Health Serv Insights. 2013;6:61–8. doi:10.4137/HSI.S11093.

Lavallee DC, Chenok KE, Love RM, Petersen C, Holve E, Segal CD, et al. Incorporating patient-reported outcomes into health care to engage patients and enhance care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(4):575–82. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1362.

Rothman ML, Beltran P, Cappelleri JC, Lipscomb J, Teschendorf B. Patient-reported outcomes: conceptual issues. Value Health. 2007;10(Suppl 2):S66–75. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00269.x.

Revicki D, Hays RD, Cella D, Sloan J. Recommended methods for determining responsiveness and minimally important differences for patient-reported outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(2):102–9. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.03.012.

Greenhalgh J. The applications of pros in clinical practice: what are they, do they work, and why? Qual Life Res. 2009;18(1):115–23. doi:10.1007/s11136-008-9430-6.

Nelson EC, Hvitfeldt HF, Reid R, Grossman D, Lindblad S, Mastanduno MP, et al. Using patient-reported information to improve health outcomes and health care value: case studies from Dartmouth, Karolinska and Group Health. The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice, 2012.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the members of the study National Advisory Committee, Susan Edgman-Levitan, Massachusetts General Hospital, Jody Gittell, Brandeis University, Elizabeth Helms, California Chronic Care Coalition, Judith Hibbard, University of Oregon, Health Sciences Center Minerva Eggleston and Michael Bolingbroke, Patient Advisors for DaVita HealthCare Partners, and Linda Richard-Bey and Lawrence Richard-Bey, Patient Advisors for Advocate Health, as well as our Patient Advisory Committees at DaVita HealthCare Partners and Advocate Health. We thank Diane Rittenhouse, MD, MPH, University of California San Francisco, for her help in developing the co-morbidity measure used for analysis. We would also like to acknowledge Christine Moore, Janelle Howe, and Frederick Gonzales at DaVita HealthCare Partners, and Sharon Gardner and Jose Elizondo, MD, at Advocate Health, for their efforts coordinating data collection efforts at the participating ACOs, Caitlin Murray of the Center for the Study of Services for project management of the Patient Survey fielding, and Zosha Kandel for assistance in preparation of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

Research reported in this publication was funded through a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Award (IHS-1310-06821) and from grant no. RFA-HS-14-011 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), Centers of Excellence Award.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Disclaimer

The statements presented in this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), its Board of Governors, or Methodology Committee.

Additional information

Registration: ClinicalTrials.gov ID# NCT02287883

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(DOCX 16 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shortell, S.M., Poon, B.Y., Ramsay, P.P. et al. A Multilevel Analysis of Patient Engagement and Patient-Reported Outcomes in Primary Care Practices of Accountable Care Organizations. J GEN INTERN MED 32, 640–647 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3980-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3980-z