Abstract

Background

Face-to-face formal evaluation sessions between clerkship directors and faculty can facilitate the collection of trainee performance data and provide frame-of-reference training for faculty.

Objective

We hypothesized that ambulatory faculty who attended evaluation sessions at least once in an academic year (attendees) would use the Reporter-Interpreter-Manager/Educator (RIME) terminology more appropriately than faculty who did not attend evaluation sessions (non-attendees).

Design

Investigators conducted a retrospective cohort study using the narrative assessments of ambulatory internal medicine clerkship students during the 2008–2009 academic year.

Participants

The study included assessments of 49 clerkship medical students, which comprised 293 individual teacher narratives.

Main Measures

Single-teacher written and transcribed verbal comments about student performance were masked and reviewed by a panel of experts who, by consensus, (1) determined whether RIME was used, (2) counted the number of RIME utterances, and (3) assigned a grade based on the comments. Analysis included descriptive statistics and Pearson correlation coefficients.

Key Results

The authors reviewed 293 individual teacher narratives regarding the performance of 49 students. Attendees explicitly used RIME more frequently than non-attendees (69.8 vs. 40.4 %; p < 0.0001). Grades recommended by attendees correlated more strongly with grades assigned by experts than grades recommended by non-attendees (r = 0.72; 95 % CI (0.65, 0.78) vs. 0.47; 95 % CI (0.26, 0.64); p = 0.005). Grade recommendations from individual attendees and non-attendees each correlated significantly with overall student clerkship clinical performance [r = 0.63; 95 % CI (0.54, 0.71) vs. 0.52 (0.36, 0.66), respectively], although the difference between the groups was not statistically significant (p = 0.21).

Conclusions

On an ambulatory clerkship, teachers who attended evaluation sessions used RIME terminology more frequently and provided more accurate grade recommendations than teachers who did not attend. Formal evaluation sessions may provide frame-of-reference training for the RIME framework, a method that improves the validity and reliability of workplace assessment.

Similar content being viewed by others

BACKGROUND

As the medical education community increasingly embraces competency-based education, there is a growing need for faculty development of assessment skills.1 In the busy clinical setting, with multiple competing demands, faculty have found brief training in a common frame of reference during their usual activities to be an acceptable and useful approach.2,3 Such frame-of-reference training helps ensure that faculty understand and share the same “mental model” of trainee performance.4 The goal of this study was to examine the impact of regularly scheduled formal evaluation sessions on faculty assessments of medical students during their internal medicine clerkship, including the frequency and accuracy of the faculty’s use of the Reporter-Interpreter-Manager/Educator (RIME) assessment framework.5

The concept of a “shared mental model” (or a shared frame of reference) comes from the literature on teamwork.6 Teams are “two or more individuals who have specific roles, perform interdependent tasks, are adaptable, and share a common goal”.7 The group of teachers working with medical students on a clinical clerkship comprises such a team. Shared mental models are “an organizing knowledge structure of the relationships between the task the team is engaged in and how the team members will interact.”8 Such a shared model offers team members a readily accessible and internalized understanding of the task, and of how team member behaviors are coordinated, tasks are anticipated, and actions can be predicted.9 Essentially, shared mental models allow team members to “draw on their own well-structured knowledge as a basis for selecting actions that are consistent and coordinated with those of their teammates.”10 Communication among team members can be difficult because of external or structural factors, such as those that might occur with a team of teachers working with students during clinical clerkships. In such circumstances, the need for a shared mental model is even greater.10

The RIME framework is a well-established framework (model)5,11 and it maps to both the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) competency framework12 and to entrustable professional activities (EPAs).13 RIME is a synthetic framework; success at each level requires that a trainee demonstrate the integration of necessary knowledge, skills, and attitudes.5 For example, to be a successful Reporter, a trainee must reliably, honestly, and accurately gather and communicate information about a patient in both spoken and written formats, and must engage with patients, families, and members of the healthcare team in the setting of real patient care. RIME can be used to establish a baseline of minimum expectations for a given context (e.g., year in medical school or year in residency training).

In many medical school clerkships, an academic leader (e.g., clerkship director, clerkship site director, or residency program director) regularly meets with faculty who are working with the trainees being evaluated.11 These formal evaluation sessions serve a tripartite function.14 First, evaluation sessions allow for collecting and recording teachers’ written and verbal assessments of trainee clinical and academic performance. Second, the evaluations from these sessions turn into multi-source feedback for the trainee. Third, the sessions facilitate faculty development in the form of real-time, case (trainee)-based frame-of-reference training, calibrating teachers’ observations. Specifically, when teachers describe trainee performance, the moderator can ask for additional details and clarifications, and can use the frame of reference with the teachers to increase a shared understanding in order to meet a common goal. Such frame-of-reference training can improve rater consistency with expert assessments.4,15

Formal evaluation sessions improve the identification of students with knowledge deficits16,17 and poor professional comportment.18 Medical students identified as marginal using RIME and formal evaluation sessions were nearly 13 times more likely to receive low ratings from their internship program directors, regardless of the specialty field of residency training.19 Implementing RIME and evaluation sessions reduces grade inflation,20 improves student and teacher satisfaction,2 and is feasible across clerkship disciplines.21 RIME has construct validity, with an association of RIME descriptors and final examination performance in an internal medicine clerkship16 and also with the “growing independence” of the learner.3 This evaluation process has also been shown to achieve a remarkable degree of inter-site consistency in a multi-site clerkship.22 Finally, in a 2005 survey, RIME or evaluation sessions were used by approximately 40 % of US internal medicine clerkships.11

The use of formal evaluation sessions as frame-of-reference training has been described3,14 but its effectiveness has not been as clearly documented. To address the goal of this study, we compared individual teacher narratives (single-teacher written and transcribed verbal comments about student performance) submitted by faculty who attended evaluation sessions (attendees) to teacher narratives submitted by faculty who did not attend the evaluation sessions (non-attendees). Our hypothesis was that attendees would use the RIME framework more frequently and more accurately in their teacher narratives than non-attendees.

METHODS

At the time of this study, the internal medicine clerkship at the Uniformed Services University consisted of 6 weeks on the inpatient wards and 6 weeks in ambulatory general and subspecialty clinics. There were seven clerkship sites throughout the continental US. At each site, there was an orientation for all teachers, which typically included a discussion of clerkship goals and objectives, with an emphasis on describing the RIME framework and expectations of student performance. This information was also provided in handouts, including emails with attachments of the orientation materials. In addition, formal evaluation sessions were facilitated by the clerkship director or site clerkship directors every 3 weeks during the 12-week clerkship, with excellent faculty and house staff attendance during the inpatient medicine portion of the clerkship.14 During the ambulatory portion of the clerkship, scheduling conflicts or teachers being located at a single teaching site remote from the main teaching hospital (e.g., community-based location) could preclude attendance at formal evaluation sessions. Outpatient faculty who were not able to attend evaluation sessions would have received the orientation materials.

Formal evaluation sessions during the ambulatory portion of the clerkship typically occurred over the lunch hour, and faculty members would come to the clerkship director or site clerkship director’s office, submit an evaluation form, and discuss their students' performance. The process can be described as follows. Briefly, at the evaluation session, the site director orients the faculty to the purpose of the session, describes the RIME framework and each level, reinforces expectations for recommendations of less than Passing, Pass (Reporter), High Pass (Interpreter), and Honors (Manager/Educator), and then asks the teacher to comment on the student’s performance (usually moving from open- to closed-ended questions). The site director will make handwritten notes of the teacher’s comments. The faculty (including all present) and site director can and will engage in dialogue to clarify comments, ask for examples, problem-solve, or seek clarification if a teacher’s recommended grade is not consistent with their verbal and/or written comments. In this way, the site director helps the teacher understand how their description links to the RIME framework and reinforces expectations.

All teachers are asked to complete an evaluation form comprising 17 domains of performance, with each domain containing a description of behaviors and performance within each of the five possible ratings (unacceptable, needs improvement, acceptable, above average, or outstanding).4 The form has a space for written comments and a description of RIME and how it is linked to a grade recommendation (e.g., Interpreter = "High Pass"). The combination of each individual teacher’s written comments and the site director’s notes of that teacher’s verbal comments at the evaluation session is called the teacher’s narrative. The combination of all teachers’ narratives on a single student is the clerkship narrative. Typically, the clerkship narrative for a student on ambulatory is approximately 1.5 typed, single-spaced pages long.

We designed a retrospective cohort study using the clerkship narrative of ambulatory internal medicine clerkship students during the 2008–2009 academic year. We did not study the inpatient portion of our clerkship, given the near-universal evaluation session attendance by that group of teachers. From the two principal clinical sites of the clerkship, we selected all clerkship narratives that contained input from at least one non-attendee teacher. The other five clerkship sites did not have a sufficient number of non-attendees and were thus excluded from the study. Attendees were teachers who attended at least one formal evaluation session during the academic year. Attendees and non-attendees spent an equivalent amount of time with their assigned student (1–2 half-days per week over a 6-week period).

From this overall clerkship narrative, we masked the individual teachers' narratives from every student who worked with at least one non-attendee in order to conceal the student name, faculty name, evaluation session attendance, clerkship site, time of the academic year, and recommended grades from the faculty. These individual teacher narratives were the unit of analysis. Six coders, all of whom had at least 5 years of experience with the RIME framework as clerkship site directors, reviewed these individual teacher narratives. Each teacher’s narrative was reviewed by at least two coders. Coders counted the number of explicit RIME utterances, (e.g., “Reporter”, “reporting”, or “reports” would be counted as Reporter) as the primary measure. If RIME was not explicitly used, coders decided whether RIME was implicit within the teacher’s narrative (e.g. “Student accurately and reliably gathers patient data” would be counted as an implicit statement of Reporter). Finally, coders assigned the grade recommendation they felt was best supported by the teacher’s narrative. In our clerkship, grades were as follows: Fail = failure to meet expectations; Low Pass = inconsistently meets expectations; Pass = Reporter; High Pass = Interpreter; Honors = Manager/Educator. Recommended grades can also reflect a transition (e.g., Pass/High Pass), and transitional recommendations were used by teachers and coders alike. Six coding conferences were held to ensure methodological consistency among coders and to resolve disagreements between coders. Rather than calculating inter-rater reliability, all disagreements between coders were resolved by consensus among the coders during the coding conferences.

Primary Outcome

The primary endpoint was the comparison of the rate of RIME utterances used in teacher narratives between attendees and non-attendees. We compared the number of explicit RIME utterances per teacher narrative and the proportion of teacher narratives with explicit RIME utterances between the two groups using chi-square or t tests, as appropriate. For both comparisons, the effect size (Cohen’s d) was calculated.

Secondary Outcomes

Secondary endpoints included a correlation of teacher-recommended grades to the student’s final grade and their total clinical points (defined below) using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. No individual teacher’s recommended grade accounted for more than 4 % of the total clinical points. We compared these correlation coefficients between attendees and non-attendees. The final student grade is a weighted summation of clinical points and exam points. Clinical points (70 % of the final grade) are a summation of grades recommended by all teachers in the clerkship, weighted by the amount of time that the teacher spent with the student. Exam points (30 % of the grade) are earned on three clerkship exams: the National Board of Medical Examiners (NBME) subject examination in medicine, and two locally developed examinations (a multiple-choice examination of commonly ordered tests, with fair internal consistency (median KR-20 of 0.5) and a video-based clinical reasoning exam (with a reliability of 0.74–0.83).23 We transformed teacher-recommended grades and expert grade assignments into a point score, with Fail = 0, Low Pass = 2, Pass = 4, High Pass = 6, and Honors = 8. This allowed us to compare teacher-recommended grades to the expert grade assignment using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. All confidence intervals and hypothesis tests for correlation coefficients were constructed using the Fisher r-to-z transformation.24

This study was approved as exempt by the institutional review board at the National Naval Medical Center in Bethesda, MD.

RESULTS

During the 2008–2009 academic year at the two clerkship sites under study, 49 of 71 (69 %) students worked with at least one non-attendee attending physician. All 293 single-teacher narratives of these 49 students were masked and reviewed by the coders. Of the 293 teacher narratives, 199 came from 82 attendee teachers and 94 came from 38 non-attendee teachers. Over the course of the year under study, attendees attended half of the evaluation sessions when they were working with students (mean 51 %, range 10–100 %).

Attendees used explicit RIME utterances more frequently than non-attendees. There were 1.9 RIME utterances per attendee narrative, compared to 0.9 per non-attendee narrative (p < 0.0001 (t test), d = 0.55). Of the attendee narratives, 69.8 % contained at least one RIME utterance, compared to 40.4 % by non-attendees (p < 0.0001 [chi square], d = 0.55).

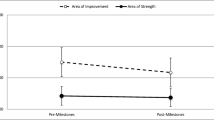

Grade recommendations from both attendees and non-attendees correlated significantly with student academic performance. Correlation coefficients were higher for attendees for both clinical points [r = 0.63, p < 0.01, 95 % CI (0.54, 0.71) vs. 0.52, p < 0.01, 95 % CI (0.36, 0.66); p = 0.21] and exam points [r = 0.41, p < 0 .02, 95 % CI (0.29, 0.52) vs. 0.26, p < 0.02, 95 % CI (0.06, 0.44)]. However, there was no statistical difference between the correlation coefficients for attendees and non-attendees for clinical points (p = 0.21) or exam points (p = 0.17).

Grades recommended by attendees correlated strongly and significantly with grades assigned by the expert coders, while grades recommended by non-attendees were moderately correlated [r = 0.72; 95 % CI (0.65, 0.78) vs. 0.47; 95 % CI (0.26, 0.64); p = 0.005 for comparison)].

Expert coders found that, overall, 60.4 % of teacher narratives contained explicit RIME utterances, while an additional 30 % used RIME implicitly. However, deeper inspection revealed that attendees used RIME far more frequently than non-attendees. Ninety-eight percent of teacher narratives by attendees contained RIME either explicitly or implicitly, compared to 74.5 % of narratives submitted by non-attendees (p < 0.001, chi square; d = 0.80).

DISCUSSION

In this retrospective cohort study in the outpatient portion of an internal medicine clerkship, teachers who attended formal evaluation sessions during which they received frame-of-reference training used explicit RIME terminology more frequently and recommended grades more consistent with experts than teachers who did not attend the formal evaluation sessions. These sessions provided a contextual approach to rater assessment, which has been shown to enhance consistency with expert raters.25 Not only were the changes statistically significant, but the effect size was moderately strong as well.

Formal evaluation sessions are feasible2 and allow for the desired direct communication between raters and academic managers.26 The impact of such training was seen in a prior study in which students recognized that approximately half of their residents and attending physicians were using RIME terminology within the first year of implementation of evaluation sessions during an inpatient clerkship.2 Attendance rates in that study were over 70 %. In our study, with a mean attendance rate of only 51 %, evaluation session attendees still used RIME terminology more effectively than non-attendees.

Because we measured evaluation session attendance only during the study year, it is possible that both groups of teachers had attended evaluation sessions at some point in the past. The difference between groups uncovered in this study may be due to additional ongoing rater training rather than episodic exposure to this form of faculty development. Our findings, like those of Battistone and others,2,27 may also reflect the ease of use and the intuitive nature of the RIME framework.

RIME was first implemented at the Uniformed Services University,5 and this may explain why we found explicit RIME use in 60 % of teacher narratives overall and implicit use in an additional 30.4 %. Even so, we believe our findings demonstrate that one can achieve consistency in evaluation and use of a specific framework when faculty are trained and guided in its use and application to real student “cases”. Proper instruction of raters in utilizing a common framework for assessment must involve “training, feedback and reflection” and “interaction with others involved.”26

While this current study focused on the outcome, and we did not audio-record the evaluation sessions, Hauer et al. did audio-record evaluation sessions,3, allowing the authors to conclude about the process (10) that “serial evaluation sessions created an environment that allowed faculty to communicate honest opinions and concerns, anticipate developmental progress, and generate collaborated learning plans…”.3 Her study corroborated findings from the teamwork literature that not only do highly functioning teams operate using a shared mental model, but they also communicate well6–10 and evaluation sessions ensure that both occur.

Since exposure to frame-of-reference training was strongly associated with adoption of the RIME terminology, the question arises regarding what to do for teachers who do not attend evaluation sessions, and an answer to this question would require further inquiry with non-attendees. These teachers could be offered faculty development in other formats, such as workshops or video-teleconferencing, but there is no data to support that these methods are any more or less effective than the brief frame-of-reference training provided during evaluation sessions.

There are limitations to our project. This was a retrospective design, and we can only report observed associations. It is difficult to fully disentangle the effect of the RIME framework from the evaluation sessions for attendees. However, the consistent finding of improvement in the attendee group speaks strongly to the added benefit of the formal evaluation sessions in helping faculty develop a shared mental model of student performance. During these sessions, the site director guides teachers toward using the RIME terminology, and this may be the reason it was used more frequently, but not universally, by attendees. Even if this were the case, we consider that to be a measure of success—the sessions are designed to help faculty learn and apply the evaluation framework. We did not collect demographic information about the teachers and thus may have overlooked other information that could have contributed to the findings. Finally, it is possible that those attending evaluation sessions were engaged in self-improvement, and thus better qualified to evaluate students, though attendance rates among attendees were still low (51 %).

CONCLUSIONS

Regularly scheduled real-time, face-to-face evaluation sessions during which teachers and clerkship directors meet to discuss performance can be an effective form of faculty development, as attendance at these evaluation sessions was strongly associated with faculty adoption of the RIME evaluation framework and framework-consistent grade assignment. Although not yet studied, evaluation sessions could play a role within other frameworks, such as the more elaborate competency framework and milestones of the ACGME. Using evaluation sessions is simple, “low-tech”, and powerful; they can be embedded in the usual activities of faculty; and they capitalize on an interactive process of dialogue not possible through the monologue of paper or electronic means.

References

Holmboe ES, Ward DS, Reznick RK, et al. Faculty development in assessment: the missing link in competency-based medical education. Acad Med. 2011;86(4):460–7. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e31820cb2a7.

Battistone MJ, Milne C, Sande MA, Pangaro LN, Hemmer PA, Shomaker TS. The feasibility and acceptability of implementing formal evaluation sessions and using descriptive vocabulary to assess student performance on a clinical clerkship. Teach Learn Med. 2002;14(1):5–10. doi:10.1207/s15328015tlm1401_3.

Hauer KE, Mazotti L, O'Brien B, Hemmer PA, Tong L. Faculty verbal evaluations reveal strategies used to promote medical student performance. Med Educ Online. 2011;16. doi:10.3402/meo.v16i0.6354

Pangaro LN, Holmboe ES. Evaluation Forms and Global Rating Scales. In: Holmboe ES, Hawkins RM, eds. Practical Guide to the Evaluation of Clinical Competence. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby, Inc.; 2008:24–43.

Pangaro L. A new vocabulary and other innovations for improving descriptive in-training evaluations. Acad Med. 1999;74(11):1203–7.

Salas E, Stout RJ, Cannon-Bowers JA, eds. The Role of Shared Mental Models in Developing Shared Situational Awareness 1993. Orlando, FL: Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University Press; 1994.

Baker DP, Day R, Salas E. Teamwork as an essential component of high-reliability organizations. Health Serv Res. 2006;41(4 Pt 2):1576–98. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00566.x.

Baker DP, Salas E, King H, Battles J, Barach P. The role of teamwork in the professional education of physicians: current status and assessment recommendations. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2005;31(4):185–202.

Westli HK, Johnsen BH, Eid J, Rasten I, Brattebo G. Teamwork skills, shared mental models, and performance in simulated trauma teams: an independent group design. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2010;18:47. doi:10.1186/1757-7241-18-47.

Mathieu JE, Heffner TS, Goodwin GF, Salas E, Cannon-Bowers JA. The influence of shared mental models on team process and performance. J Appl Psychol. 2000;85(2):273–83.

Hemmer PA, Papp KK, Mechaber AJ, Durning SJ. Evaluation, grading, and use of the RIME vocabulary on internal medicine clerkships: results of a national survey and comparison to other clinical clerkships. Teach Learn Med. 2008;20(2):118–26. doi:10.1080/10401330801991287.

Rodriguez RG, Pangaro LN. AM Last Page. Mapping the ACGME competencies to the RIME framework. Acad Med. 2012;87(12):1781. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e318271eb61.

Pangaro L, ten Cate O. Frameworks for learner assessment in medicine: AMEE Guide No. 78. Med Teach. 2013;35(6):e1197–210. doi:10.3109/0142159x.2013.788789.

Hemmer PA, Pangaro L. Using formal evaluation sessions for case-based faculty development during clinical clerkships. Acad Med. 2000;75(12):1216–21.

Gorman CA, Rentsch JR. Evaluating frame-of-reference rater training effectiveness using performance schema accuracy. J Appl Psychol. 2009;94(5):1336–44. doi:10.1037/a0016476.

Griffith CH 3rd, Wilson JF. The association of student examination performance with faculty and resident ratings using a modified RIME process. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(7):1020–3. doi:10.1007/s11606-008-0611-3.

Hemmer PA, Pangaro L. The effectiveness of formal evaluation sessions during clinical clerkships in better identifying students with marginal funds of knowledge. Acad Med. 1997;72(7):641–3.

Hemmer PA, Hawkins R, Jackson JL, Pangaro LN. Assessing how well three evaluation methods detect deficiencies in medical students' professionalism in two settings of an internal medicine clerkship. Acad Med. 2000;75(2):167–73.

Lavin B, Pangaro L. Internship ratings as a validity outcome measure for an evaluation system to identify inadequate clerkship performance. Acad Med. 1998;73(9):998–1002.

Battistone MJ, Pendleton B, Milne C, Battistone ML, Sande MA, Hemmer PA, Shomaker TS. Global descriptive evaluations are more responsive than global numeric ratings in detecting students' progress during the inpatient portion of an internal medicine clerkship. Acad Med. 2001;76(10 Suppl):S105–7.

Espey E, Nuthalapaty F, Cox S, et al. To the point: Medical education review of the RIME method for the evaluation of medical student clinical performance. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197(2):123–33. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2007.04.006.

Durning SJ, Pangaro LN, Denton GD, et al. Intersite consistency as a measurement of programmatic evaluation in a medicine clerkship with multiple, geographically separated sites. Acad Med. 2003;78(10 Suppl):S36–8.

Hemmer PA, Dong T, Durning SJ, Pangaro L. Novel Examination for Evaluating Medical Student Clinical Reasoning: Reliability and Association with Patients Seen. Mil. Med. 2015. In Press.

Fisher R. On the 'probable error' of a coefficient of correlation deduced from a small sample. Metron. 1921;1:3–32.

Govaerts MJ, Schuwirth LW, Van der Vleuten CP, Muijtjens AM. Workplace-based assessment: effects of rater expertise. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2011;16(2):151–65. doi:10.1007/s10459-010-9250-7.

Govaerts MJ, Van de Wiel MW, Schuwirth LW, Van der Vleuten CP, Muijtjens AM. Workplace-based assessment: raters' performance theories and constructs. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2012. doi:10.1007/s10459-012-9376-x.

Bloomfield L, Magney A, Segelov E. Reasons to try 'RIME'. Med Educ. 2007;41(11):1104. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02884.x.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to express their gratitude to Eric S. Holmboe, MD, for his thoughtful review of an earlier version of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

The study was reviewed and approved as exempt from further review by the institutional review board at the National Naval Medical Center in Bethesda, MD.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors, and do not represent the opinions of the Uniformed Services University, the Department of Defense, or other federal agencies.

Previous Presentations

This publication is based on research presented at the Clerkship Directors in Internal Medicine National Meeting in Anaheim, CA, on October 22, 2011.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hemmer, P.A., Dadekian, G.A., Terndrup, C. et al. Regular Formal Evaluation Sessions are Effective as Frame-of-Reference Training for Faculty Evaluators of Clerkship Medical Students. J GEN INTERN MED 30, 1313–1318 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-015-3294-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-015-3294-6