ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

Since 1990, the National Cancer Institute (NCI) and Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) have collaborated to create linked data resources to improve our understanding of patterns of care, health care costs, and trends in utilization. However, existing data linkages have not included measures of patient experiences with care.

OBJECTIVE

To describe a new resource for quality of care research based on a linkage between the Medicare Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS®) patient surveys and the NCI’s Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) data.

DESIGN

This is an observational study of CAHPS respondents and includes both fee-for-service and Medicare Advantage beneficiaries with and without cancer. The data linkage includes: CAHPS survey data collected between 1998 and 2010 to assess patient reports on multiple aspects of their care, such as access to needed and timely care, doctor communication, as well as patients’ global ratings of their personal doctor, specialists, overall health care, and their health plan; SEER registry data (1973–2007) on cancer site, stage, treatment, death information, and patient demographics; and longitudinal Medicare claims data (2002–2011) for fee-for-service beneficiaries on utilization and costs of care.

PARTICIPANTS

In total, 150,750 respondents were in the cancer cohort and 571,318 were in the non-cancer cohort.

MAIN MEASURES

The data linkage includes SEER data on cancer site, stage, treatment, death information, and patient demographics, in addition to longitudinal data from Medicare claims and information on patient experiences from CAHPS surveys.

KEY RESULTS

Sizable proportions of cases from common cancers (e.g., breast, colorectal, prostate) and short-term survival cancers (e.g., pancreas) by time since diagnosis enable comparisons across the cancer care trajectory by MA vs. FFS coverage.

CONCLUSIONS

SEER-CAHPS is a valuable resource for information about Medicare beneficiaries’ experiences of care across different diagnoses and treatment modalities, and enables comparisons by type of insurance.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Since 1998, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has sponsored annual administrations of the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS®) surveys to assess the health care experiences of Medicare enrollees in Medicare Advantage (MA) and fee-for-service (FFS) health plans.1 Previous studies have used data from these surveys to assess differences in patient experiences by plan types (i.e., MA vs. FFS), racial/ethnic groups, and care delivery setting (e.g., hospital inpatient, outpatient, nursing home).2 – 7 Existing research has also examined the experiences of specific subgroups of patients, such as those with depression or kidney disease.8 , 9 However, to date, the CAHPS measures have had limited use in assessing the experiences of patients with cancer.

Currently, there are approximately 13.7 million cancer survivors in the United States.10 , 11 The prevalence of cancer is projected to grow significantly in the future, given improvements in detection and treatment, and the growing size of the population aged 65 and older.10 – 12 Furthermore, the process of receiving appropriate cancer care is often complex, time-consuming, expensive, and fraught with administrative barriers.13 – 16 Due to these complexities, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) and the National Cancer Institute (NCI) have released several reports that emphasize the importance of patient-centered care in the treatment of cancer patients and the use of patient-centered measures to evaluate the quality of care that these patients receive.13 , 14 , 17 , 18

This paper describes a new data set that links data from Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) with CAHPS Medicare survey data and results from a collaborative effort between NCI, the SEER registries, and CMS. These data provide a rich opportunity for analyses of Medicare beneficiaries’ experiences with their care at various stages of the cancer care continuum, including: the initial year after diagnosis, when patients are most likely to receive cancer treatments; the years of post-treatment follow-up care; those of long-term cancer survivorship; and the final end-of-life care phase. Analyses from these data have the potential to fill an important gap in existing knowledge by enabling comparisons of patients’ care experiences between MA and FFS beneficiaries and between patients with and without cancer. For Medicare FFS beneficiaries, the SEER-CAHPS data set also allows for the evaluation of their health care utilization and costs of care.

METHODS

Data Sources

Four principal sources of data comprise the linked SEER-CAHPS data set: 1) CAHPS data for all Medicare MA and FFS beneficiaries between 1998 and 2010; 2) SEER data for CAHPS survey respondents with cancer living in a SEER region; 3) Medicare claims data for all FFS beneficiaries who were CAHPS survey respondents; and 4) Medicare Enrollment Database (EDB) eligibility and demographic data for all CAHPS survey respondents.

CAHPS

The CAHPS program began in 1995 and has produced a suite of survey and reporting kits to assess patient experiences with health care in the United States.19 CMS has sponsored annual administration of CAHPS surveys to Medicare MA beneficiaries since 1998 and to FFS beneficiaries since 2001. The CAHPS Medicare-stratified sampling methodology is discussed in detail by Zaslavsky et al. (2012).20 Surveys are distributed by mail with telephone follow-up of non-respondents. The CAHPS Medicare surveys assess patient reports of multiple aspects of their care and include multi-item composites to summarize reports, which are described below:

-

Getting needed care

-

How often was it easy to get appointments with specialists?

-

How often was it easy to get the care, tests, or treatment you thought you needed through your health plan?

-

-

Getting care quickly

-

When you needed care right away, how often did you get care as soon as you thought you needed?

-

Not counting times you needed health care right away, how often did you get an appointment for your health care at a doctor’s office or clinic as soon as you thought you needed?

-

How often did you see the person you came to see within 15 min of your appointment time?

-

-

Doctor Communication

-

How often did your personal doctor explain things in a way that was easy to understand?

-

How often did your personal doctor listen carefully to you?

-

How often did your personal doctor show respect for what you had to say?

-

How often did your personal doctor spend enough time with you?

-

-

Health plan customer service

-

How often did your health plan’s customer service give you the information or help you needed?

-

How often did your plan’s customer service staff treat you with courtesy and respect?

-

The surveys also elicit global ratings of the personal doctor, specialists, overall health care, and the health plan. While some CAHPS items have changed over time, the core concepts assessed remained fairly constant. CAHPS surveys also collect information on a variety of patient characteristics, including: age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, smoking status, general health status, comorbid health conditions (e.g., heart disease, stroke, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), language of the survey (English or Spanish), and proxy assistance. In addition, CAHPS surveys field quality of life measures, including SF-36 measures of physical and mental health for certain years.

SEER

The SEER program collects incidence and survival information for all new cancer cases in defined U.S. geographic areas, with a unique case identification number for each patient. The SEER program began in 1973 and now covers approximately 28 % of the U.S. population, with data from nine states (California, Connecticut, Iowa, New Mexico, Utah, Hawaii, Kentucky, New Jersey, and Louisiana) and from selected regions in Georgia, Michigan, and Washington.21 , 22 SEER collects demographic and disease-specific information on cancer patients, including: age, gender, race/ethnicity, marital status, month and year of diagnosis, primary tumor site, tumor morphology, and stage. SEER registries also collect data on treatment, including surgical and radiation treatments provided as the first course of therapy.

Medicare Claims

For Medicare FFS beneficiaries who responded to the CAHPS surveys, we obtained Standard Analytic Files from CMS: Inpatient, Outpatient, Hospice, and Home Health Agency. We also obtained the National Claims History (NCH) Durable Medical Equipment file and the Carrier file, which contains claims submitted by non-institutional providers such as physicians, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners. For inpatient information, including hospital and skilled nursing facilities, we used the Medicare Provider Analysis and Review file. All of these claims files contain diagnosis codes, procedure codes, dates of service, provider information, service charges, and Medicare payments. All files include a health insurance claim number (HICN) for each beneficiary that can be used to identify the same beneficiary across files. Notably, claims files were not available for Managed Care beneficiaries.

Medicare Enrollment Database (EDB)

The EDB is the master file that contains enrollment and entitlement data for all Medicare beneficiaries. For each CAHPS respondent, we obtained the following information: Part A and Part B coverage, HMO enrollment, third-party payer of premiums in either Part A or Part B, Medicaid enrollment, disability status, state of residence, age, gender, race/ethnicity, date of birth, and date of death (if applicable).

File Linkage

We identified beneficiaries who responded to the CAHPS FFS or MA surveys between 1998 and 2010, and linked them to the SEER data and Medicare claims, for FFS beneficiaries. To determine if a survey was taken in a SEER region, we compared the date the CAHPS survey was received with the respondent’s location at that time. For surveys from 2007 to 2010, we have the exact date of survey receipt; for earlier years, we imputed a receipt date using the midpoint of the survey collection interval range. Respondents with at least 1 day of residence in a SEER state in the year the survey was received or in the year immediately prior were identified as residing in a SEER state. Because some surveys were administered early in a given year and the CAHPS Medicare items ask about care received in the previous 6 months, we included a 1-year look-back period to obtain a more comprehensive understanding of respondents’ care experiences.

To link CAHPS respondents to the SEER data, we used a prior linkage of persons in SEER who had been matched to Medicare enrollment to create the SEER-Medicare data. As part of the SEER-Medicare linkage, the SEER cancer registries send individual identifiers for all persons in their files to be matched against Medicare’s master enrollment file. The resulting file contains the SEER case number paired with the person’s HICN. CAHPS respondents included in the SEER data were designated as the cancer group. We defined a comparison group that consisted of all Medicare beneficiaries who did not have cancer (as defined by our SEER linkage), but who did have at least 1 day of residence in a SEER region either in the year that they completed the CAHPS survey or in the year prior. Data from beneficiaries who did not have cancer according to SEER data and did not reside in a SEER region in the year of or the year prior to the survey were excluded from this comparison group, but their information was retained in the data set. For all CAHPS FFS respondents, we obtained and linked Medicare claims from CMS for all available years (i.e., 2002–2011). We anticipate the SEER-CAHPS data set will be publicly available to researchers in late 2016.

Data Description and Analysis

In order to describe the strengths and the scope of the SEER-CAHPS data set, we conducted several descriptive analyses, examining specific subgroups that may be of interest to researchers. We identified the number of CAHPS respondents classified as having cancer, the number of those without cancer, and those who lived and did not live in a SEER region during the time of the survey. For each of these groups of respondents, we calculated the proportion who took the MA and FFS surveys for each survey year.

After looking at the overall sample, we then conducted further analyses focused on the cancer and non-cancer comparison groups. We describe several key characteristics of the respondents in these two groups, stratified by insurance type. The majority of the variables from CAHPS that are presented in this paper were collected from single survey items: gender, race/ethnicity, education, Spanish survey, and general health status. For the race/ethnicity variable, patients of Hispanic origin received a Hispanic classification regardless of other race status. Smoking behavior and proxy assistance were both constructed from multiple survey items.23

Age was derived using the date that the survey was received by CMS and the respondent’s date of birth as it appeared on the EDB. SEER region was based upon the date of survey receipt and was taken from the year in which the survey was received for both the cancer and non-cancer groups. For 99 % of these respondents, SEER region status in the survey year remained unchanged from the prior year.

SEER data include multiple measures of cancer stage. We report results based on SEER historic stage, which includes the following categories: In situ; localized; regional; distant; or unstaged. Prostate cancer is the only cancer that uses the “localized/regional” combined category. Treatment data from SEER indicates if the patient’s initial course of therapy included surgery, radiation, or both. Given the incomplete ascertainment of chemotherapy data by SEER registries, chemotherapy is not included in the public-use SEER data.

For researchers interested in specific cancers, we conducted stratified analyses by FFS and MA and identified the total number of respondents for 19 different cancer types. For each cancer, we identified the timing of the CAHPS survey with respect to date of cancer diagnosis (i.e., prior to first cancer diagnosis, within 2, 3–5, 6–10, and 11+ years after diagnosis). It should be noted that these time points were chosen to capture multiple phases in the cancer care trajectory, but can be grouped differently (e.g., diagnosed within 1 year). For the four most prevalent cancers (breast, prostate, colorectal, and lung), we conducted stratified analyses by FFS/ MA status and present the number of cases by time since diagnosis for each cancer stage and by initial treatment type (i.e., surgery, radiation, or both) (Appendix Tables 7, 8 and 9).

In total, the analytic file contains data from 3,059,747 Medicare beneficiaries, representing 3,383,661 CAHPS surveys taken between 1998 and 2010. The number of surveys exceeds the number of individual beneficiaries, because a small percentage of respondents answered the survey multiple times. For those with multiple surveys, we analyzed only their first survey taken.

RESULTS

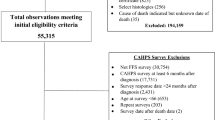

Figure 1 provides information on the number of respondents in the SEER-CAHPS data set by their cancer status, SEER status, and insurance plan (FFS/MA) at the time of the survey. For respondents in the cancer group, Figure 1 provides information on the number of individuals who took surveys either before or after their first cancer diagnosis. The average annual CAHPS response rate was 71 % (Appendix Table 5).

Table 1 provides information on variables and topic areas in the data set. Table 2 presents information on demographic characteristics and health status, stratified by cancer status and Medicare coverage (MA/FFS). In total, the sample residing in the SEER area includes 150,750 individuals with cancer and 571,318 individuals without cancer with similar proportions of MA (65 %) and FFS surveys (35 %) in each group. A greater proportion of respondents with cancer were 75 years and older, and male, relative to those without cancer among both MA and FFS beneficiaries. Race/ethnicity and education levels were similar between groups, although higher proportions of minorities were in the non-cancer cohort for both MA and FFS insurance types. FFS respondents had a higher percentage of dual eligibles (i.e., those with Medicare and Medicaid) compared to those with MA coverage for both the cancer (13 vs. 6 %) and non-cancer (21 vs. 11 %) cohorts. Health status and smoking status were similar between the cancer and non-cancer cohorts and across insurance types.

Tables 3 and 4 provide information for MA and FFS respondents by cancer type and time since diagnosis. For the most common cancers (i.e., prostate, breast, colorectal), there are relatively large sample sizes at each of the major time periods post-diagnosis. Across each individual type of cancer, most surveys were taken after the first cancer diagnosis and provide sizable proportions of cases diagnosed within 2, 3–5, 6–10, and 11 or more years. For example, among individuals with colorectal cancer covered by MA insurance, there are between 1652 and 2535 cases at each of these time points (Table 3). Among their FFS counterparts, there are between 868 and 1608 colorectal cancer cases (Table 4).

Among individuals diagnosed with more aggressive cancers, such as pancreatic cancer, the majority of surveys occurred prior to their cancer diagnosis, likely due to the short-term survival associated with these cancers. With more than 1000 cases of pancreatic cancer among individuals with MA insurance, researchers would be able to examine questions that have implications for end-of-life care and make comparisons to those with FFS coverage. Similarly, given the late stage at diagnosis, most of the lung cancer cases occur during the earlier time points in the cancer care trajectory, with sizable samples enabling comparisons by insurance type.

Additional information about SEER-CAHPS respondents is available in the Appendix tables, including data on response rates, number of respondents by SEER region, and stage information among cancer survivors by MA and FFS insurance status. Notably for respondents with the four most common cancers (i.e., breast, colorectal, lung, and prostate), localized stage was the most common, and the relative distribution of stages was similar across insurance types (Appendix Table 9).

DISCUSSION

Patient-centered care is an important component of high quality care delivered to individuals with cancer. However, limited information exists regarding patient experiences with cancer care, such as access to needed services and the quality of patient–provider communication.24 The SEER-CAHPS data set provides an important opportunity to increase understanding of the care delivered to older cancer patients in the U.S. over multiple years.

Pairing CAHPS surveys with claims and SEER data makes it possible to stratify patients beyond what is possible with the survey data, the claims information, or SEER data alone. Cancer patients have complex health care needs and extensive interaction with the health care system, including diagnostic services, treatment, post-treatment follow-up, and end-of-life care. Therefore, quality of care is a central aspect of their experiences in navigating cancer care and making important medical decisions. While researchers have begun to explore patient experiences, more studies are needed to provide comparative information about the care experiences of cancer patients and their non-cancer counterparts, many of whom may be living with other chronic conditions. SEER-CAHPS linked data will allow investigators to directly compare large groups of these patients by assessing their care across different points in the cancer care continuum.

Additionally, researchers will be able to compare patient experiences by type of cancer or treatment modality (e.g., cancer stage, surgical and/or radiation treatment). This linkage will allow them to explore issues by time in the disease’s course; for example, is a more recently diagnosed patient likely to report better or worse experiences with health care than a long-term survivor? Researchers will also be able to link patient experiences to outcomes, such as mortality or survival, and determine if experiences and outcomes vary by demographic characteristics.

Furthermore, this linkage enables comparisons of different models of healthcare coverage, since Medicare beneficiaries can enroll in either MA or FFS plans. Research comparing experiences of care by coverage type may provide valuable insights to policymakers in the era of healthcare reform and help Medicare beneficiaries make informed decisions about their care.

Researchers can also assess cancer patients in certain phases of their disease trajectory or in specific care settings (e.g., hospice care). For instance, the SEER-CAHPS data can help to better understand patients’ perceptions of care at the end of life, which is an area of growing interest.25 Experiences can be compared between individuals in skilled nursing facilities and other patients, as well as between patients undergoing more and less aggressive treatment. Moreover, the experiences of cancer patients can be compared to experiences of patients who ultimately die of causes other than cancer, and this may help address gaps in the existing literature.

Finally, large enough sample sizes exist within subgroups to compare patients in several different categories (e.g., stage, cancer type, racial/ethnic group). Additional cancer cases will also become available, with future data linkages enabling further comparisons. For those with FFS coverage, the data include a 10-year trajectory of claims data that provides a more informed overall picture of the beneficiary. In assessing trends in patient experiences over time, researchers can also explore how these are influenced by changes in Medicare, especially those changes that have the most influence on patients’ experiences with care.

Although these data can provide powerful new insights into the health care experiences of Medicare beneficiaries, some limitations exist. While claims data are relatively complete for FFS beneficiaries, no claims data are available for MA beneficiaries. This gap in claims information may limit sample sizes for some analyses and precludes analyses that rely on claims to compare FFS and MA. Furthermore, while we have a large sample of cancer survivors representing several different cancers in the SEER-CAHPS data set, analyses limited to certain specific cancer types and stages might not be feasible.

Additionally, the data included in the SEER database cover 28 % of the U.S. population and are only available for specific regions. Since there may be differences in demographics and care received in unrepresented areas, caution must be exercised when making inferences from this sample to the entire Medicare population.

CAHPS surveys have also changed over the years. As a result, researchers must contend with a diversity of survey types, not only within a given year, but also across different years. In analyzing CAHPS survey data that span more than a decade, some challenges may exist related to changes over time. However, there are survey items, such as the global ratings of care and composite scores of patient experiences, that are consistently available.

In conclusion, the SEER-CAHPS linkage provides opportunities to explore many research areas that existing data sets cannot address. SEER-CAHPS is a unique and comprehensive source of information about Medicare beneficiaries that includes patients’ experience of care (from CAHPS), their diagnoses and treatment modalities (from SEER), and their Medicare claims activity (from CMS). These data can provide important information about the quality, cost, and utilization of health care among beneficiaries, and contribute significantly to evaluations of Medicare policies. Researchers can also conduct analyses examining patient experiences among individuals with and without cancer, many of whom may be living with other chronic conditions, such as diabetes or heart disease. In summary, this data set has the potential to inform many research areas, address gaps in the existing literature, and assist clinicians and policymakers to improve the quality of care for all Medicare beneficiaries, particularly those diagnosed with cancer.

REFERENCES

Schnaier JA, Sweeny SF, Williams VS, Kosiak B, Lualin JS, Hays RD, Harris-Kojetin LD. Special issues addressed in the CAHPS survey of medicare managed care beneficiaries. Consumer assessment of health plans study. Med Care. 1999;37(3 Suppl):MS69–MS78.

Elliott MN, Haviland AM, Orr N, Hambarsoomian K, Cleary PD. How do the experiences of medicare beneficiary subgroups differ between managed care and original medicare? Health Serv Res. 2011;46(4):1039–1058. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2011.01245.x.

Farley DO, Elliott MN, Haviland AM, Slaughter ME, Heller A. Understanding variations in medicare consumer assessment of health care providers and systems scores: California as an example. Health Serv Res. 2011;46(5):1646–1662. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2011.01279.x.

Goldstein E, Elliott MN, Lehrman WG, Hambarsoomian K, Giordano LA. Racial/ethnic differences in patients’ perceptions of inpatient care using the HCAHPS survey. Med Care Res Rev. 2010;67(1):74–92. doi:10.1177/1077558709341066.

Rodriguez HP, von Glahn T, Elliott MN, Rogers WH, Safran DG. The effect of performance-based financial incentives on improving patient care experiences: a statewide evaluation. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(12):1281–1288. doi:10.1007/s11606-009-1122-6.

Weech-Maldonado R, Hall A, Bryant T, Jenkins KA, Elliott MN. The relationship between perceived discrimination and patient experiences with health care. Med Care. 2012;50(9 Suppl 2):S62–S68. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e31825fb235.

Weinick RM, Elliott MN, Volandes AE, Lopez L, Burkhart Q, Schlesinger M. Using standardized encounters to understand reported racial/ethnic disparities in patient experiences with care. Health Serv Res. 2011;46(2):491–509. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01214.x.

Paddison CA, Elliott MN, Haviland AM, Farley DO, Lyratzopoulos G, Hambarsoomian K, Dembosky JW, Roland MO. Experiences of care among medicare beneficiaries with ESRD: Medicare Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) survey results. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;61(3):440–449. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.10.009.

Martino SC, Elliott MN, Kanouse DE, Farley DO, Burkhart Q, Hays RD. Depression and the health care experiences of medicare beneficiaries. Health Serv Res. 2011;46(6pt1):1883–1904. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2011.01293.x.

Siegel R, DeSantis C, Virgo K, Stein K, Mariotto A, Smith T, Cooper D, Gansler T, Lerro C, Fedewa S, Lin C, Leach C, Cannady RS, Cho H, Scoppa S, Hachey M, Kirch R, Jemal A, Ward E. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62(4):220–241. doi:10.3322/caac.21149.

American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2012. Atlanta: American Cancer Society. Available at: http://www.cancer.org/research/cancerfactsstatistics/cancerfactsfigures2012/index Accessed on 2 Dec 2014.

Howlander N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al. SEER cancer statistics review, 1975–2008. Bethesda MD: National Cancer Institute; 2011.

Institute of Medicine. Cancer care for the whole patient: meeting psychosocial health needs. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2007.

Institute of Medicine. Patient-Centered Cancer Treatment Planning: Improving the Quality of Oncology Care – Workshop Summary. 2011.

Taplin SH, et al. Introduction: understanding and influencing multilevel factors across the cancer care continuum. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2012;2012(44):2–10.

Zapka J, et al. Multilevel factors affecting quality: examples from the cancer care continuum. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2012;2012(44):11–19.

Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E. From cancer patient to cancer survivor: lost in translation. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2006.

Epstein RM, Street RL Jr. Patient-centered communication in cancer care: promoting healing and reducing suffering. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2007.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality 2011. CAHPS: Surveys and Tools to Advance Patient Centered Care. Available at: http://www.cahps.ahrq.gov/. Accessed on 2 Dec 2014.

Zaslavsky AM, Ayanian JZ, Zaborski LB. The validity of race and ethnicity in enrollment data for medicare beneficiaries. Health Serv Res. 2012;47(3):3000–3021.

National Cancer Institute 2011. Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results Available at: http://seer.cancer.gov/. Accessed on 2 Dec 2014.

Warren J, Klabundee CN, Schrag D, et al. Overview of the SEER-Medicare Data: Content, Research Applications, and Generalizability to the United States Elderly Population. Medical Care 40(8 Suppl):IV-3-18, August 2002.

Elliott MN, Beckett MK, Chong K, Hambarsoomians K, Hays RD. How do proxy responses and proxy-assisted responses differ? Health Serv Res. 2008;43(3):833–848. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2007.00820.x.

Arora NK, Reeve BB, Hays RD, Clauser SB, Oakley-Girvan I. Assessment of quality of cancer-related follow-up care from the cancer survivor’s perspective. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1280–1289.

Elliott MN, Haviland AM, Cleary PD, Zaslavsky AM, Farley DO, Klein DJ, Edwards CA, Beckett MK, Orr N, Saliba D. Care experiences of managed care medicare enrollees near the end of life. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(3):407–412. doi:10.1111/jgs.12121.

Acknowledgments

SEER is supported by an interagency agreement with Indian Health Service in Alaska (No. Y1-PC-0064) and the following contract agreements: Connecticut Department of Public Health (No. HHSN261201000024C); Emory University (No. HSN261201000025C); University of Iowa (No. HHSN261201000032C); University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey (No. HHSN261201000027C); University of Utah (No. HHSN261201000026C); Cancer Prevention Institute of California (No. HHSN261201000140C); University of Hawaii (No. HHSN261201000037C); University of New Mexico (No. HHSN261201000033C); Public Health Institute (No. HHSN261201000034C); University of Southern California (No. HHSN261201000035C); Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center (No. HHSN261201000029C); University of Kentucky Research Foundation (No. HHSN261201000031C); Wayne State University (No. HHSN261201000028C); and Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center (No. HHSN261201000030C). Data from this paper was presented at the Academy Health Annual Research Meeting on June 8–10, 2014.

Conflict of Interest

No authors have any conflicts to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

APPENDIX

APPENDIX

Table 5

Table 6

Table 7

Table 8

Table 9

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chawla, N., Urato, M., Ambs, A. et al. Unveiling SEER-CAHPS®: A New Data Resource for Quality of Care Research. J GEN INTERN MED 30, 641–650 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-014-3162-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-014-3162-9