Abstract

Residential transience may contribute to adverse mental health. However, to date, this relationship has not been well-investigated among urban, impoverished populations. In a sample of drug users and their social network members (n = 1,024), we assessed the relationship between transience (frequently moving in the past 6 months) and depressive symptoms, measured by the CES-D, among men and women. Even after adjusting for homelessness, high levels of depressive symptoms were 2.29 [95%CI = 1.29–4.07] times more likely among transient men compared to nontransient men and 3.30 [95% CI = 1.10–9.90] times more common among transient women compared to nontransient women. Stable housing and mental health services need to be available, easily accessible, and designed so that they remain amenable to utilization under transient circumstances.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Housing instability, a common problem among individuals living in urban environments, has been linked to poor health status, HIV risk behaviors, violence, and mental health problems including depression.1–4

Housing instability has been operationalized in a variety of ways including being “literally homeless” (i.e., living on the street or outdoors) or living in a temporary housing situation such as a shelter or single-room occupancy (SRO).5 , 6 There is a tendency among researchers to focus on the physical place or structure of residence. Other dimensions of housing stability, such as residential transience or frequently changing residences, have begun to receive attention in the published literature.7 , 8

Increasing evidence suggests that frequent moving may have health implications. In a study of a variety of housing situations, Weir and colleagues found that individuals who reported having two or more residences in the past 6 months were more likely to engage in risky sex behaviors including unprotected intercourse and exchanging sex for money or drugs.9 Likewise, our previous research demonstrated that residential transience was associated with HIV drug-related behaviors including sharing needles and going to a shooting gallery.10 Transient individuals also tended to be younger, have lower income, and were less likely to have a main sexual partner than nontransient respondents, suggesting that these individuals may have differing needs.10

Research among children has consistently demonstrated a negative association between residential mobility and mental health problems.11 In a longitudinal study, Gilman and colleagues found that moving three or more times before the age of 7 years was significantly associated with depression diagnosis by age 14.12 Although prior research suggests that relocation and moving is associated with poor mental health problems including anxiety and schizophrenia, much of this research is based on population studies and has focused on moving as an infrequent stressful life event.13–15

There is a lack of research that has explored the impact of frequent relocation on the psychological well-being of urban-disadvantaged adults. Individuals with low socioeconomic status have higher rates of depression compared to the general population.16 This association may be because of stressful life events, less control of life events, and fewer social and economic resources to meet the demands of these stressors. It is likely that similar factors contribute to transience, which may heighten vulnerability to additional stressors in turn.

In addition, the experience of relocation may influence men and women differently, which would have differential impacts on their psychological well-being. In a study conducted in Madrid, Munoz and colleagues compared depression levels between homeless individuals (defined as sleeping mainly on the street, shelters, abandoned buildings, or outdoors) to a group of individuals who were at risk for homelessness (defined as utilizing services designed to serve homeless individuals).17 Both groups reported high rates of depressive symptoms, but rates of depression were highest among homeless women. In a longitudinal study of over 10,000 Chicago residents, Magdol found a significant relationship between residential mobility and depression.18 In an analysis stratified by gender, women who reported at least one move within a 5-year period had significantly higher CES-D scores compared to women who did not move. There was no significant association between moving and depression among men. These findings both indicate that housing instability is linked to psychological well-being and that important gender differences may exist.

Women experience depression more often than men.19 , 20 Several explanations for this disparity have been offered including differences in opportunities, increased stress among women, role captivity, lack of economic resources, biological factors, and role strain.21 Although researchers have not examined gender differences in the link between transience and depression, recent research indicates that women, compared to men, experience higher exposure to housing-related stressors.22 In a community sample of couples, Nazroo and researchers found that women were more likely to experience depression after a stressful life event related to children, housing, or reproduction compared to their male partners.23 As the effect did not hold for other life stressors, the researchers suggested that the association was because of women’s increased roles in these areas.

The purpose of the present study is to examine the association between residential transience and depressive symptoms in a sample of inner-city residents. We also explore if this relationship exists for both men and women. The rationale for exploring gender differences is twofold. First, as there is a disparity in depression rates among men and women, research is needed to identify additional contributors of depression. Second, the experience of frequent relocation may affect men and women differently as moving may be a result of different types of circumstances such as change in partner or eviction. We anticipated that even after accounting for homelessness, frequency of residential relocation would be associated with depressive symptoms.

Methods

Data were collected from participants in the STEP into Action (STEP) study. The STEP study is an HIV prevention intervention for active drug injectors and their social network members. Participants (i.e., primary participants) were recruited through targeted outreach and local advertisements. Eligibility criteria included: (1) 18 years or older; (2) no participation in other HIV prevention or social network studies in the past year; (3) self-reported injection of heroin or cocaine; (4) willingness to introduce at least one social network member to the study; and (5) Baltimore City resident. Primary participants referred their social network members to the study. Eligibility criteria for social network members included: (1) 18 years or older and one of the following: (2) self-reported heroin or cocaine use; (3) drug partner of primary participants (i.e., used drugs with primary participant); or (4) sex partner of primary participant. Although all primary participants were drug users, not all social network members used drugs.

Baseline data were collected through face-to-face interviews that lasted approximately 2 h. Participants were compensated with $35 for completion of the baseline visit. All study protocols were approved by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Institutional Review Board before implementation.

Measures

Residential transience was assessed by asking participants “In the past 6 months, how many times did you move?” Responses were recoded as “one or no moves in the past 6 months” and “two or more moves.”

Depressive symptoms were assessed through administration of the Centers for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D).24 The CES-D is a 20-item scale with four response categories including: (1) rarely or none of the time; (2) some or a little of the time; (3) occasionally or a moderate amount of time; (4) most or all of the time. A summary score for all responses was computed, and the variable was recoded as high depression symptomology or “depressed” (16 or higher) vs. low symptomology or “not depressed” (less than 16). Previous research has shown that CES-D scores of 16 or higher are predictive of clinical depression in community and urban samples.25 , 26 Thus, this cutpoint is used as a standard proxy for depressive symptoms.

In addition to these main variables of interest, we also measured several sociodemographics, such as age, employment, and education, and drug-related behaviors (refer to Table 1). Homelessness was measured by asking participants “At any time in the past 6 months, have you been homeless?” Two drug-related behaviors were assessed: (1) injection drug use in the past 6 months; and (2) use of heroin, cocaine, or crack (regardless of administration) in the past 6 months. Because of the skewed distribution, several sociodemographic characteristics were dichotomized.

Data Analysis

The data for the present study were collected from primary and network participants (n = 1,024) who completed baseline study visits from March 2004 through March 2006. Data were analyzed using Stata Version 8.0 (StataCorp, 2005) and SPSS 15.0 (SPSS, 2006). Exploratory analysis was conducted to examine the distributions and associations among study variables. Data were stratified by gender. As the outcome (depression) was a dichotomous variable, data were analyzed using logistic regression. In each of the gender multivariate models, we controlled for several covariates, including homelessness, education, race, employment, prison history, and drug use, that were associated with depression in the bivariate analyses. As the sample was comprised of participants and their social network members, the general estimating equation (GEE) was employed to account for correlation among variables. GEE adjusts for variance within and between clusters of social network members.27

Results

Sample Characteristics

The characteristics of the study population are presented in Table 1. Data were collected from 1,024 participants who were primarily African American (82.1%) with a mean age of 43 years. Approximately 60% (n = 621) of the participants were male and 40% (n = 403) were female. Whereas 142 (13.9%) participants moved two or more times in the past 6 months, approximately one third (33.7%) reported homelessness in the past 6 months. Most had used heroin, cocaine, or crack in the past 6 months (94.9%), many (82%) through injection drug use. Close to half completed 12 or more years of education (45.9%) and had a monthly income less than $500 (50.9%). The majority had a current main partner at the time of the survey (59.7%), and over one quarter had spent time in prison in the past 6 months (26.8%).

Comparison of Males and Females

In this sample, 89 (14.3%) males and 53 (13.2%) females reported moving two or more times in the past 6 months. There were several statistically significant differences by gender. Males were more likely to report recent homelessness (36.7% vs. 29.0%, p < 0.05), to be employed at least part-time (21.3% vs. 9.2%, p < 0.001), to have spent time in prison in the past 6 months (31.6% vs. 19.4%, p < 0.001), and to have injected drugs in the past 6 months (86.3% vs. 75.9%, p < 0.001). Women were more likely to have monthly incomes less than $500 (p < 0.001). Approximately 59% of males and 71.5% of females (p < .001) reported high levels of depressive symptoms (CES-D score ≥16).

Mental Health Data

Table 2 displays the data on the comparison between depressed participants and participants who were not depressed as reported through CES-D scores. As shown in the table, severe depressive symptoms did not vary by age, income level, having a main partner, and injection drug use. Depression was more common among individuals who moved two or more times (p < 0.001) and who reported homelessness in the past 6 months (p < 0.001). In addition, depression was more common among participants who were African Americans (p < 0.01), had less than a high school education (p < 0.01), were not employed (p < 0.001), spent time in prison (p < 0.01), and used heroin or cocaine (p < 0.01) in the past 6 months.

Multivariate Results

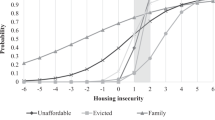

Table 3 shows the results of multivariate analyses conducted separately for males and females. Overall, depression was more common among women than men. Transient males were 2.29 times more likely to have higher depressive symptoms than nontransient males (95%CI = 1.29, 4.07). Among women, transient individuals were 3.30 times more likely to be depressed (95%CI = 1.10, 9.90). Males who reported being employed at least part-time (p < 0.01) and had at least a high school diploma (p < 0.05) had a lower likelihood of being depressed.

Among females, being employed at least part-time (p < 0.05) and being African American (p < 0.05) were associated with decreased odds of depressive symptoms.

Discussion

This study has shown that residential transience or frequent relocation in a 6-month period is associated with depression, independent of homelessness. Although the association between transience and depression was not significantly different for men and women, the strength of this association was higher among women. This finding may be a result of differences between men and women, as shown in the descriptive analyses. Consistent with other research, our study showed significantly higher levels of depressive symptoms among women compared to men.19 , 20 In addition, the men in this study were more likely to be employed at least part-time and to report monthly incomes greater than $500. Employment was an independent predictor of depression for both men and women, but income was not associated with depression. Nonetheless, it is possible that economic advantage among the men helps protect against the negative mental health implications of transience. It may also be that transience among women is driven more strongly by economic need, which may compound the effect of transience as a mental health stressor.

Our sample represented a marginalized inner-city population with high levels of drug use and low socioeconomic status. However, controlling for drug use in the final multivariate model provides evidence that the association between transience and depression is not unique only to drug users; thus, we believe that the findings do have relevance for nondrug users and for low-income urban residents regardless of drug use. The relationship between transience and depression may be explained by life in an urban environment. Housing-related stressors, such as physical decay of the structure and high crime activity, are common in urban neighborhoods.28 , 29 These housing stressors may have a negative impact on one’s psychological well-being. Another contributing factor may be neighborhood violence. Crime and violence are common stresses in urban neighborhoods that contribute to depression.30 Individuals who experience violence or live in a violent neighborhood may be more likely to relocate and experience depressive symptoms.

In addition, the impetus for moving among inner-city residents may be different than for the general population. Research among the general population points to life-course changes, such as employment, housing conditions, and neighborhood characteristics, as common contributors to residential moves.31 , 32 In contrast, our qualitative data (data not shown) indicates that low-income urban residents move for a variety of negative and positive reasons, including changes in relationships, eviction, becoming sober, financial problems, and disasters such as fires. In contrast, it is possible that moving because of an unpredictable event such as eviction or loss of job may contribute more strongly to increased depressive symptoms. It is also likely that each of these events leads to stress and is further detrimental to one’s psychological well-being. Instability in one area of life is likely to exacerbate other difficulties, creating further stress and challenges to one’s ability to achieve stable life circumstances. Because women are often caregivers and guardians of children, they may experience additional concerns under transient circumstances.

One pathway through which transience may impact depression is disruption or change in social relationships. Frequent relocation may challenge one’s ability to maintain social relationships. Specifically, individuals who move frequently may experience decreased social support and disruption of existing social networks.33 Likewise, individuals who move around may have greater difficulty developing social bonds with other people thus leading to social isolation. Particularly under stressful circumstances, this disruption in social networks may further contribute to depressive symptoms and may make it more difficult to deal with associated stressors.

Another explanation for the association between transience and depression is that frequently moving around may interfere with accessing health and social services and other resources. Duchon and researchers found that residential mobility was associated with lack of a usual source of health care and dependence on emergency rooms.7 The authors suggest that mobility may prevent individuals from being attached to care providers. Thus, they are more likely to utilize emergency rooms as their usual source of care. Similarly, transience is likely to disrupt consistent and appropriate mental health care and utilization of other social services, such as employment and public assistance. Likewise, transient individuals may not have a permanent address that is required for a variety of services. In addition to formal health and social services, transience may also interrupt informal sources of care such as self-help and church groups.

Although we found a significant association between transience and depression, it is important to note that an unmeasured factor, such as occurrence of a traumatic event, may contribute to both transience and depression and may be partially responsible for this association. Women in unstable living circumstances often become victims of violence.34 In a qualitative study among women, Tomas and Dittmar found that women relocate from one residence to another as a way of coping with unfortunate circumstance such as interpersonal abuse.35 This abuse would cause both the transience and depression.

The present study has several limitations that should be noted. First, the data were cross-sectional. In addition, there is a temporal limitation. Transience was assessed in the past 6 months, yet depressive symptoms were measured in the past week. Our data do not include information on the length of time since the last move and, therefore, we cannot determine whether recent transience is more highly associated with recent depressive symptoms. Finally, the study population was a disadvantaged group which limits its generalizability.

Many researchers have shown that homelessness is detrimental to mental health; our data suggest that frequent relocation is also a substantial contributor to poor mental health status.36 Therefore, these findings indicate that housing strategies should be implemented such that affordable housing is plentiful and accessible, but also that strategies are needed to ensure that housing can be sustained over time. This may include emergency assistance programs and low threshold housing options that make housing more attainable for those who use substances or have severe mental illness. In addition, economic programs which offer assistance to individuals who are at risk of losing their home are needed, such as emergency cash assistance and budgeting guidelines. Likewise, job training and placement services may overcome any financial barriers that lead to transience. In addition to providing stable housing, mental health services need to be available and easily accessible among urban residents and designed so that they remain amenable to utilization under transient circumstances.

References

Hwang SW, Tolomiczenko G, Kouyoumdjian FG, Garner RE. Interventions to improve the health of the homeless: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2005;29(4):311–319.

Pavao J, Alvarez J, Baumrind N, Induni M, Kimerling R. Intimate partner violence and housing instability. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(2):143–146.

Rosenthal D, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Batterham P, Mallett S, Rice E, Milburn NG. Housing stability over two years and HIV risk among newly homeless youth. AIDS Behav. 2007;11(6):831–841.

Schanzer B, Dominguez B, Shrout PE, Caton CL. Homelessness, health status, and health care use. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(3):464–469.

Hahn JA, Kushel MB, Bangsberg DR, Riley E, Moss AR. BRIEF REPORT: the aging of the homeless population: fourteen-year trends in San Francisco. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(7):775–778.

Thompson VV, Ragland KE, Hall CS, Morgan M, Bangsberg DR. Provider assessment of eligibility for hepatitis C treatment in HIV-infected homeless and marginally housed persons. AIDS. 2005;19(Suppl 3):S208–S214.

Duchon LM, Weitzman BC, Shinn M. The relationship of residential instability to medical care utilization among poor mothers in New York City. Med Care. 1999;37(12):1282–1293.

Henny KD, Kidder DP, Stall R, Wolitski RJ. Physical and sexual abuse among homeless and unstably housed adults living with HIV: prevalence and associated risks. AIDS Behav. 2007;11(6):842–853.

Weir BW, Bard RS, O’Brien K, Casciato CJ, Stark MJ. Uncovering patterns of HIV risk through multiple housing measures. AIDS Behav. 2007;11(Suppl 2):31–44.

German D, Davey MA, Latkin CA. Residential transience and HIV risk behaviors among injection drug users. AIDS Behav. 2007;11(Suppl 2):21–30.

Dong M, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, et al. Childhood residential mobility and multiple health risks during adolescence and adulthood: the hidden role of adverse childhood experiences. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159(12):1104–1110.

Gilman SE, Kawachi I, Fitzmaurice GM, Buka L. Socio-economic status, family disruption and residential stability in childhood: relation to onset, recurrence and remission of major depression. Psychol Med. 2003;33(8):1341–1355.

Bolan M. The mobility experience and neighborhood attachment. Demography. 1997;34(2):225–237.

Lix LM, DeVerteuil G, Walker JR, Robinson JR, Hinds AM, Roos LL. Residential mobility of individuals with diagnosed schizophrenia: a comparison of single and multiple movers. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2007;42(3):221–228.

Stokols D, Shumaker SA. The psychological context of residential mobility and well-being. J Soc Issues. 1982;38(3):147–171.

Lorant V, Deliege D, Eaton W, Robert A, Philippot P, Ansseau M. Socioeconomic inequalities in depression: a meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157(2):98–112.

Munoz M, Crespo M, Perez-Santos E. Homeless effects on men’s and women’s health. Int J Ment Health. 2005;34(2):47–61.

Magdol L. Is moving gendered? The effects of residential mobility on the psychological well-being of men and women. Sex Roles. 2002;47(11/12):553–560.

Nolen-Hoeksema S, Larson J, Grayson C. Explaining the gender difference in depressive symptoms. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1999;77(5):1061–1072.

Weissman MM, Klerman GL. Sex differences and the epidemiology of depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1977;34(1):98–111.

Bird CE, Rieker PP. Gender matters: an integrated model for understanding men’s and women’s health. Soc Sci Med. 1999;48(6):745–755.

Kendler KS, Thornton LM, Prescott CA. Gender differences in the rates of exposure to stressful life events and sensitivity to their depressogenic effects. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(4):587–593.

Nazroo JY, Edwards AC, Brown GW. Gender differences in the onset of depression following a shared life event: a study of couples. Psychol Med. 1997;27(1):9–19.

Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1(3):385–401.

Boyd JH, Weissman MM, Thompson WD, Myers JK. Screening for depression in a community sample. Understanding the discrepancies between depression symptom and diagnostic sales. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1982;39:1195–1200.

Kim MT, Han HR, Hill M, Rose L, Roary M. Depression, substance use, adherence behaviors, and blood pressure in urban hypertensive black men. Ann Behav Med. 2003;26(1):24–31.

Zeger SL, Liang KY. Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics. 1986;42(1):121–130.

Smith CA, Smith CJ, Kearns RA, Abbott MW. Housing stressors, social support and psychological distress. Soc Sci Med. 1993;37(5):603–612.

Wong YL, Piliavin I. Stressors, resources, and distress among homeless persons: a longitudinal analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2001;52(7):1029–1042.

Curry A, Latkin C, Davey-Rothwell M. Pathways to depression: the impact of neighborhood violent crime on inner-city residents in Baltimore, Maryland, USA. Soc Sci Med. 2008;in press.

Clark WAV, Ledwith V. Mobility, housing stress, and neighborhood contexts: evidence from Los Angeles. Environ Plann A. 2006;38(1077):1093.

Shumaker SA, Stokols D. Residential mobility as a social issue and research topic. J Soc Issues. 1982;38(3):1–19.

Sluzki CE. Disruption and reconstruction of networks following migration/relocation. Fam Syst Med. 1992;10(4):359–363.

Wenzel SL, Tucker JS, Hambarsoomian K, Elliott MN. Toward a more comprehensive understanding of violence against impoverished women. J Interpers Violence. 2006;21(6):820–839.

Tomas A, Dittmar H. The experience of homeless women: an exploration of housing histories and the meaning of home. Hous Stud. 1995;10(4):493–516.

Martens WH. A review of physical and mental health in homeless persons. Public Health Rev. 2001;29(1):13–33.

Acknowledgement

Sources of Support

This work was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (grant no. 1RO1 DA016555).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Davey-Rothwell, M.A., German, D. & Latkin, C.A. Residential Transience and Depression: Does the Relationship Exist for Men and Women?. J Urban Health 85, 707–716 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-008-9294-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-008-9294-7