Abstract

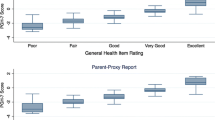

Quality of life (QoL) is an important index that allows health practitioners to understand the overall health status of an individual. One commonly used reliable and valid QoL instrument with parallel items on parent and child questionnaires, the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory Version 4.0 (PedsQL), has been being developed since 1997. However, the use of parent- and child-reported PedsQL is still under development. Using multitrait-multimethod (MTMM) analyses and absolute agreement analyses across parent and child questionnaires can further help health practitioners understand the construct of PedsQL, and the feasibility of PedsQL in clinical. We analyzed the questionnaires of 254 parent–child dyads. MTMM through confirmatory factor analyses and percent of smallest real difference (SRD%) were used for analyzing. Our results supported the construct validity of the PedsQL. Four traits (physical, emotional, social, and school) and two methods (parent-proxy reports and child self-reports) were distinguished by MTMM. Moreover, the results of absolute agreements suggested that parent-rated and child-rated PedsQL are close (SRD% = 17.88–30.55 %); thus, a parent-rated PedsQL can be a secondary outcome representing a child’s health. We conclude that the PedsQL is useful for measuring children’s QoL, and has helpful clinical implications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Please note that Model 2 also provides the information of agreement between parents and children. However, we used other statistical methods (including ICC, SEM, and SRD) to examine the agreement based on the reason that Model 2 can only provide the overall agreement. In other words, Model 2 provides the agreement of the entire QoL, while other statistical methods we used provide the agreement for each QoL domain (e.g., physical and psychosocial domains).

The ICC shares the same terms of variances in the repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA): variance between participants and that within participants. Of the variance within participants, it can be separated as variance between methods and residual variance. Therefore, we could have the following model: xij = μ + αi + βj + εij, where β represents for participants, α for methods (i.e., parent- and child-rated PedsQL in this study), and ε for residual. Then, the ICC can be computed as β variance divided by the sum of α, β, and ε variances. Based on the formula, we could easily know that a high value of ICC shows a fair degree of agreement between the methods. In addition, ICC simultaneously accounts for bias (i.e., whether children rate the PedsQL lower or higher than parents do) and association (i.e., whether children and parents understand the meaning of the PedsQL in the same way).

SEM equals to the square root of the error variance: SEM = √σ2 error = √σ2 methods + √σ2 residual, where σ2 methods represents for the variance of child- and parent-rated PedsQL. Because ICC is computed as σ2 methods divided by total σ2, 1−ICC = σ2 residual divided by total σ2. SEM then can be calculated as: SEM = σtotal × √(1−ICC). Hence, based on the formula of SEM, we could examine the differences between child- and parent-rated PedsQL.

SRD = 1.96 × SEM × √2, where 1.96 represents the 95 % confidence interval from a normal distribution, and √2 is used to account for the additional uncertainty introduced by using difference scores from the 2 independent measurements with the same variances (in our study, they are child-rated and parent-rated PedsQL). The variance of the difference scores (SD2 diff) can be computed from three sources: variances of the child-rated (SD2 child) and parent-rated (SD2 parent) scores, and the covariance (covchild, parent) between them. Therefore, SD2 diff = SD2 child−2 × covchild, parent + SD2 parent. Because the Pearson correlation (r) can be defined as the ratio of the covariance divided by the product of the corresponding SDs (i.e., SDchild × SDparent), covchild, parent is substituted by r × SDchild × SDparent. And SD2 diff = SD2 child−2 × r × SDchild × SDparent + SD2 parent. Assuming child-rated and parent-rated PedsQL have equal variability in the population, we can get SD2 diff = 2 × SD2 child−2 × r × SD2 child = 2 × SD2 child × (1−r). Taken square root in both sides: SDdiff = SDchild × √2 (1−r). Assuming child-rated and parent-rated PedsQL are independent, the Pearson correlation r is zero, and the last term is reduced to SDdiff = SDchild × √2. Hence, using √2 to multiply SEM is to conservatively consider the possibly largest uncertainty.

The primary benefit of using SRD% is that it is independent of the units of measurement, and readers can easily understand the magnitude of a bias is. Another benefit of using the total range is that total range is the same across samples, while standard deviation will be changed in different samples.

Model 1 only accounts for QoL trait; Model 2 only accounts for different methods (i.e., child- and parent-rated PedsQL); Model 3 accounts for one general QoL trait and two methods; Models 4 and 5 account for both four QoL traits and two methods. Therefore, comparing Models 4 and 1 helps us understand the method effects; Models 4 and 2 helps us examine the trait effects, that is, whether child- and parent-rated QoL were satisfactory converged, and indicates convergent validity. The difference between Models 4 and 3 is that Model 4 used QoL as separated traits, while Model 3 used QoL as one general trait. Therefore, comparing the two models help we understand the discriminant between the four QoL traits, and discriminant validity can be tested.

References

Campbell, D. T., & Fiske, D. W. (1959). Convergent and discriminant validation by the multitrait-multimethod matrix. Psychological Bulletin, 56, 81–105.

Chan, K. S., Mangione-Smith, R., Burwinkle, T. M., Rosen, M., & Varni, J. W. (2005). The PedsQL: reliability and validity of the short-form generic core scales and asthma module. Medical Care, 43(3), 256–265.

Chen, H.-M., Hsieh, C.-L., Lo, S. K., Liaw, L.-J., Chen, S.-M., & Lin, J.-H. (2007). The test-retest reliability of 2 mobility performance tests in patients with chronic stroke. Neurorehabilitation and Neural Repair, 21(4), 347–352.

Chen, H.-M., Chen, C.-C., Hsueh, I.-P., Huang, S.-L., & Hsieh, C.-L. (2009). Test-retest reproducibility and smallest real difference of 5 hand function tests in patients with stroke. Neurorehabilitation and Neural Repair, 23(5), 435–440.

Chun, C.-A., Moos, R. H., & Cronkite, R. C. (2005). Culture: a fundamental context for the stress and coping paradigm. In P. T. P. Wang & L. C. J. Wong (Eds.), Handbook of multicultural perspectives on stress and coping (pp. 29–53). New York: Springer.

Cremeens, J., Eiser, C., & Blades, M. (2006a). Characteristics of health-related self-report measures for children aged three to eight years: a review of the literature. Quality of Life Research, 15(4), 739–754.

Cremeens, J., Eiser, C., & Blades, M. (2006b). Factors influencing agreement between child self-report and parent proxy-reports on the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory™ 4.0 (PedsQL™) generic core scales. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 4, 58.

Eiser, C., & Morse, R. (2001). Can parents rate their child’s health-related quality of life? Results of a systematic review. Quality of Life Research, 10(4), 347–357.

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s consequences (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Hoyle, R. H., & Panter, A. T. (1995). Writing about structural equation modeling. In R. H. Hoyle (Ed.), Structural equation modeling: Concepts, issues, and application. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Huang, C.-J., & Michael, W. B. (2002). Multitrait-multimethod analyses of scores on a Chinese version of the dimensions of self-concept scale. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 62(2), 355–372.

Huguet, A., & Miró, J. (2008). Development and psychometric evaluation of a Catalan self- and interviewer-administered version of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory version 4.0. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 33(1), 63–79.

Jozefiak, T., Larsson, B., Wichstrom, L., Mattejat, F., & Ravens-Sieberer, U. (2008). Quality of life as reported by school children and their parents: a cross-sectional survey. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 6, 34.

Kenny, D. A., & Kashy, D. A. (1992). Analysis of multitrait-multimethod matrix by confirmatory factor analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 112, 165–172.

Kline, R. B. (1998). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford Press.

Kobayashi, K., & Kamibeppu, K. (2010). Measuring quality of life in Japanese children: development of the Japanese version of the PedsQL. Pediatrics International, 52, 80–88.

Limbers, C. A., Newman, D. A., & Varni, J. W. (2008). Factorial invariance of child self-report across age subgroups: a confirmatory factor analysis of ages 5 to 16 years utilizing the PedsQL 4.0 generic core scales. Value in Health, 11(4), 659–668.

Lin, C.-Y., Luh, W.-M., Yang, A.-L., Su, C.-T., Wang, J.-D., & Ma, H.-I. (2012a). Psychometric properties and gender invariance of the Chinese version of the self-report Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory Version 4.0: short form is acceptable. Quality of Life Research, 21(1), 177–182.

Lin, C.-Y., Su, C.-T., & Ma, H.-I. (2012b). Physical activity patterns and quality of life of overweight boys: a preliminary study. Hong Kong Journal of Occupational Therapy, 22(1), 31–37.

Lin, C.-Y., Luh, W.-M., Cheng, C.-P., Yang, A.-L., Su, C.-T., & Ma, H.-I. (2013a). Measurement equivalence across child self-reports and parent-proxy reports in the Chinese version of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory Version 4.0. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 44(5), 583–590.

Lin, C.-Y., Su, C.-T., Wang, J.-D., & Ma, H.-I. (2013b). Self-rated and parent-rated quality of life for community-based obese and overweight children. Acta Paediatrica, 102(3), e114–e119.

Marsh, H. W., & Bailey, M. (1991). Confirmatory factor analysis of multitrait-multimethod data: a comparison of alternative models. Applied Psychological Measurement, 15, 47–70.

Marsh, H. W., & Grayson, D. (1995). Latent variable models of multitrait-multimethod data. In R. H. Hoyle (Ed.), Structural equation modeling: Concepts, issues, and applications (pp. 177–198). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Portney, L. G., & Watkins, M. P. (2000). Foundations of clinical research: Applications to practice (2nd ed., p. 708). Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall Health.

Rankin, G., & Stokes, M. (1998). Reliability of assessment tools in rehabilitation: an illustration of appropriate statistical analyses. Clinical Rehabilitation, 12(3), 187–199.

Ravens-Sieberer, U., & Bullinger, M. (1998). Assessing health-related quality of life in chronically ill children with the German KINDL: first psychometric and content analytical results. Quality of Life Research, 7(5), 399–407.

Ravens-Sieberer, U., & Bullinger, M. (2000). KINDL R -Questionnaire for measuring health-related quality of life in children and adolescents revised version manual. http://www.kindl.org/english/manual/. Accessed 17 April 2015.

Ravens-Sieberer, U., Erhart, M., Wille, N., Wetzel, R., Nickel, J., & Bullinger, M. (2006). Generic health-related quality-of-life assessment in children and adolescents: methodological considerations. PharmacoEconomics, 24(12), 1199–1220.

Rosner, B. (2006). Fundamentals of biostatistics (6th ed.). Belmont: Thomson Brooks/Cole.

Roy, K. M., Roberts, M. C., & Canter, K. S. (2013). Anomalies in measuring health-related quality of life: using the PedsQL 4.0™ with children who have peanut allergy and their parents. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 8, 511–518.

Schweizer, K. (2010). Some guidelines concerning the modeling of traits and abilities in test construction. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 26(1), 1–2.

Sheffler, L. C., Hanley, C., Bagley, A., Molitor, F., & James, M. A. (2009). Comparison of self-reports and parent proxy-reports of function and quality of life of children with below-the-elbow deficiency. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, 91, 2852–2859.

Su, C.-T., Wang, J.-D., & Lin, C.-Y. (2013). Child-rated versus parent-rated quality of life of community-based obese children across gender and grade. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 11, 206.

Su, C.-T., Ng, H.-S., Yang, A.-L., & Lin, C.-Y. (2014). Psychometric evaluation of the Short Form 36 Health Survey (SF-36) and the World Health Organization Quality of Life Scale Brief Version (WHOQOL-BREF) for patients with schizophrenia. Psychological Assessment, 26(3), 980–989.

Thorndike, E. L. (1920). A constant error in psychological ratings. Journal of Applied Psychology, 4, 469–477.

Tomás, J. M., Hontangas, P. M., & Oliver, A. (2000). Linear confirmatory factor models to evaluate multitrait-multimethod matrices: the effects of number of indicators and correlation among methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 35(4), 469–499.

Trandis, H. C. (1995). Individualism & collectivism. Bulder: Westview Press.

Upton, P., Eiser, C., Cheung, I., Hutchings, H. A., Jenney, M., Maddocks, A., et al. (2005). Measurement properties of the UK-English version of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory 4.0 (PedsQL) generic core scales. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 3, 22.

Upton, P., Lawford, J., & Eiser, C. (2008). Parent–child agreement across child health-related quality of life instruments: a review of the literature. Quality of Life Research, 17(6), 895–913.

Varni, J. W., Seid, M., & Rode, C. A. (1999). The PedsQL: measurement model for the pediatric quality of life inventory. Medical Care, 37(2), 126–139.

Varni, J. W., Seid, M., & Kurtin, P. S. (2001). PedsQL 4.0: reliability and validity of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory version 4.0 generic core scales in healthy and patient populations. Medical Care, 39(8), 800–812.

Varni, J. W., Limbers, C. A., & Newman, D. A. (2008). Factorial invariance of the PedsQLTM 4.0 generic core scales self-report across gender: a multigroup confirmatory factor analysis with 11,356 children ages 5 to 18. Applied Research in Quality of Live, 3, 137–148.

World Health Organization. (1993). Study protocol for the World Health Organization project to develop a Quality of Life assessment instrument (WHOQOL). Quality of Life Research, 2(2), 153–159.

Young, D., Limbers, C. A., & Grimes, G. R. (2013). Is body mass index or percent body fat a stronger predictor of health-related quality of life in rural Hispanic youth? Applied Research in Quality of Life, 8, 519–529.

Acknowledgments

This research was, in part, supported by the Ministry of Education, Taiwan, R. O. C. The Aim for the Top University Project to the National Cheng Kung University (NCKU).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cheng, CP., Luh, WM., Yang, AL. et al. Agreement of Children and Parents Scores on Chinese Version of Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory Version 4.0: Further Psychometric Development. Applied Research Quality Life 11, 891–906 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-015-9405-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-015-9405-z