Abstract

Exercise addiction is an extensively studied topic in the sport science and psychology literature as reflected by the more than 1000 papers published in the field. However, only about 12 cases were published in the area, which may suggest that there is difficulty in reaching and studying affected individuals. Relying on the Components Model of Addiction, we performed an extensive search on non-scholar websites (i.e. popular media websites) and identified 100 cases that met the eligibility criteria. These cases reflect the several physical, psychological and social consequences that may accompany the dysfunction, as well as numerous exercise activities to which individuals may become addicted. The findings also raise the question whether women are more affected than men, or perhaps women are more open than men to disclose their problem, as based on the four to one ratio of the identified cases. The current work supports the large volume of research in the field of exercise addiction, because either the prevalence of the dysfunction is greater than expected, or people are more open to disclose their problem on Internet sites.

Similar content being viewed by others

Exercise is a form of planned physical activity that requires energy expenditure to sustain the work of the muscles (Caspersen et al. 1985). Exercising to a level at which an individual loses control over the exercise behaviour turns into a compulsory activity, resulting in a dysfunction referred to as exercise addiction (Griffiths 1997; Szabo 2010) or exercise dependence (Hausenblas and Downs 2002). Exercise addiction is listed among behavioural addictions (Egorov and Szabo 2013) like gambling disorder, but due to inconclusive and limited scientific evidence for being a unique mental dysfunction, the condition is not listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association 2013). Apart from the characteristic symptoms of addictions (in general), such as salience, mood modification, withdrawal symptoms, tolerance and relapse, on which the Components Model of Addiction (Griffiths 2005) is based, to be classified as an addiction one’s exercise behaviour must trigger, physical, psychological, or social harm (Szabo 2010). Indeed, without negative consequence(s), even an excessive amount of exercise may not be considered dysfunctional (Szabo and Kovacsik 2019). Further, actual cases of exercise addiction (with identifiable negative consequences) are seldom reported in the literature and, therefore, the objective of this work was to explore whether such cases could be identified on popular media websites.

Although one study reported that out of 300 fitness centre participants 125 (42%) could be addicted to exercise (Lejoyeux et al. 2008), the estimated risk for exercise addiction is ‘relatively low’, ranging from 0.3 to 0.5%, as based on a Hungarian representative population-wide study (Monók et al. 2012). However, even this figure is enormously high. If one considers the population of the United Kingdom, which is almost 68 million (Worldmeters.com 2019), and that 13% of this nation’s population claims to exercise regularly (five or more times per week), while 34% claims to exercise with some regularity (one to four times per week) based on recent statistical data (European Commission 2018), then only among those who exercise five or more times per week we might find over 25 thousand people at risk or affected by exercise addiction (0.3% of the 13% of the 68 million)! However, if one searches the over 1000 articles published on exercise addiction (Szabo and Kovacsik 2019), will hardly find a few (i.e. 12) case studies published in scholastic papers. Consequently, one may conclude that there is an exaggerated research effort in the area, which based on the number of identified cases is not justified, and that the few cases reported in the literature are insufficient to support a clause for exercise addiction to be included in a future edition of the DSM.

Indeed, we could only identify a few published cases of exercise addiction. The first was reported by Veale (1995) on a 27-year woman who was disinterested in life apart from running. A later case covered the morbid exercise pattern of a 25-year-old female martial artist (Griffiths 1997). The case of a 50-year-old male cyclist was published 7 years later (Kotbagi et al. 2014). One year later, in a self-help book about exercise addiction, Schreiber and Hausenblas (2015) present nine cases of exercise addiction, which starts with the case of the first author. This latter was also published in an academic journal (Hausenblas et al. 2017). These cases add up to 12, suggesting that currently there is approximately one identified case of exercise addiction for every100 article published in the area (Szabo and Kovacsik 2019).

Given that the media also shows interest in exercise addiction, we hypothesized that we will be able to identify more cases of exercise addiction in the public media than in the scholastic literature. The rationale for this presumption was that academicians and researchers could hardly reach out for exercises addicts and that health professionals getting in contact with them might be preoccupied with helping the patients rather than doing research. The objective of the work was to reveal that the abundant scholastic research in the area may not be in vain, because there might be significantly more cases of exercise addiction than the dozen published in academic writings.

Method

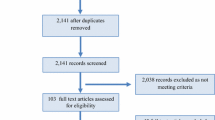

We searched the Internet by using the Google search engine and employing relevant and appropriate search terms (Table 1), such as exercise addiction and exercise addict. The three key inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) articles must be in English language, (2) at least one of the six symptoms of the Components Model of Addiction (Griffiths 2005) must be identified through the reading of the article, and (3) the affected person must have had suffered at least one physical, psychological or social damage (negative consequence). We, the two authors, agreed 100% on the presence of the set criteria in the sequentially coded articles that can be verified in Table 2. While we did not impose a period limit, we imposed an upper limit to the search number, which was set to 100. This limit is a delimitation of the study set because it was deemed enough to expose a much wider existence of exercise addiction than currently could be estimated from the scholastic literature. In fact, this number is nearly nine (9) times more than the cases available in academic writings. The search strategy is summarized in Table 1. The link to each case is provided in the Appendix and it is also available, with a screenshot (a saved picture) of the page reporting the included article, at the Mendeley data repository (DOI: 10.17632/sdcj3vgchz.1).

Results

The results are summarized in Table 2. The table reveals that there are four times more cases of exercise addiction reported by women, or reported on women (81) than men (19) in the 100 cases found on the Internet. Only 35 articles reported the age of the individual, which ranged from 24 to 59 years (M = 34.65 ± SD = 9.24). Body building and running were forms of exercises involved in more than half of the 100 cases. Cycling was reported in 15 cases. More than half of the cases involved more than one form of exercise. In most cases, readers could identify four or more symptoms from the Components Model of Addictions (Griffiths 2005), and most cases involved an identifiable loss or damage in two out of three categories (i.e. physical, psychological or social). Finally, nearly one fifth (19) of the cases exposed a loss or damage in all three categories.

Discussion

In appreciating the current results, one should keep in perspective that the bulk of the over 1000 articles published in the field reported cross-sectional studies using questionnaires to assess the risk for exercise addiction on a Likert scale spectrum. Two of the extensively employed tools are the Exercise Addiction Inventory (Terry et al. 2004) and Exercise Dependence Scale (Hausenblas and Downs 2002). The results based on these tools could often trigger a ‘false alarm’ in that high-risk scores may not necessarily reflect problematic exercise behaviour (Szabo 2018). Indeed, questionnaires are not diagnostic tools. However, since exercise addiction is not listed in the DSM, there is no ‘official’ diagnosis criteria for the dysfunction. Experts in the field rely on the DSM criteria form gambling disorder (Hausenblas and Downs 2002), or the symptom-based Components Model of Addiction (Griffiths 2005), which was also adopted in the current study. In addition to symptoms, the peer-reviewed published case studies all contain some sort of harm or damage to the individual due to her/his exercise habits (Szabo 2018). This criteria of at least on damage or negative consequence, whether physical, psychological or social, was also set in the current study. However, even those meeting the selection criteria (all included 100 cases) of experiencing one or more symptoms and negative consequences cannot be diagnosed in lack of accepted clinical diagnosis criteria. It is obvious that the 100 cases reported here are not superior to the 12 already published cases, but they are not inferior either, because neither in the scholastic publication nor in these Internet articles could the diagnosis of exercise addiction be established, while in both sources there were symptoms as well as negative consequences to the affected individual stemming from her/his unhealthy exercise behaviour.

One is likely to appreciate the fact that not all cases of exercise addiction surface on the Internet. Only a few affected individuals may feel that their case could help them (writing it out) or others (warning, preventing) by sharing their story. Consequently, we may expect more similar cases to exist, which may partially dissolve the concern about the disproportionally high number of research articles on exercise addiction (> 1000) in contrast to the reported cases (12; Szabo and Kovacsik 2019). Nevertheless, the path of researchers and that of the exercise addiction-affected individuals may seldom cross. The latter group when awaking to the problem turns to specialized health professionals and not to researchers, while researchers try to screen for exercise addicts within healthy exercising samples. Moreover, the screening tools used by researchers merely screens for individuals at risk (and stops there), who might never become addicted to exercise (Szabo 2018), and therefore, prevalence estimates based on this method may be inaccurate (Maraz et al. 2015).

Despite the finding that in accord with the 12 published cases, the current 100 cases also suggest that more women may be affected than men, we think that an alternative explanation may be that women are keener to disclose their story than men. Nevertheless, a literature review suggests that women may be more prone to exercise addiction than men (Fattore et al. 2014), but contrary evidence also exists (Szabo et al. 2013). Apparently, the gender differences in exercise addiction call for more research in the future. The present study also confirms that body building, running and cycling may be linked most closely to exercise addiction. However, in most cases there were multiple forms of exercise involved. While age was only disclosed in 35 out of the 100 cases, it appears that adults of any age could be affected.

The current study was able to identify 100 cases of exercise addiction based on symptoms and consequences criteria accepted in the literature. This number is nearly nine times higher than the number of cases of exercise addiction reported in scholastic writings over the past 25 years. The disproportion may be related to the search medium. In a research setting, it is hard to meet individuals affected by exercise addiction. In the public media, like the Internet, victims of the dysfunction apparently share their experiences for various reasons. If we could locate 100 cases meeting the criteria for exercise addiction, it is likely that the number of affected exercisers may be much higher. Therefore, we can reinforce that exercise addiction is a real problem that affects numerous individuals. Research to date could not produce enough evidence, as illustrated by only 12 cases published in 25 years, which might be one reason why the dysfunction is not included in the DSM-5. The 100 cases reported here may stimulate a new avenue of research on public media where scholars can have an easier access to exercise-addicted individuals.

The current study has some limitations stemming primarily from its delimitations. For example, we examined only English websites, used only the Google search engine and limited the number or records to 100. It is possible that more and/or more severe cases could be located if one uses other search engines and other sets no language delimitation. Another limitation, beyond the authors’ control, is the reliability of the publicly reported cases.

Conclusion

This study identified 100 cases of exercise addiction, meeting the current research (not clinical) classification of the dysfunction, on non-academic websites. This finding, contrasted with the meagre number of earlier reported cases, justifies the wider existence of exercise addiction as a real problem for the affected individuals. It also justifies the abundant research in this scholastic area, as reflected by over 1000 publications in field. Simultaneously, it warns researchers in the area that they may be searching in the dark, because screening out real addicts from among a group of healthy exercisers, especially with a risk-assessing instrument, is unlikely to be fruitful. Indeed, it was recommended that questionnaire-screening should be followed up with interviews to identify the addicted exercisers (Szabo et al. 2015). All cases presented here include symptoms and consequences of dysfunctional exercise and support the existence of exercise addiction as a real, and perhaps more prevalent than estimated, problem. Future investigations should examine these individuals more closely to develop a set of robust clinical criteria which will help in the diagnosis, and inclusion in the next DSM, of the disorder.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Caspersen, C. J., Powell, K. E., & Christenson, G. M. (1985). Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: definitions and distinctions for health-related research. Public Health Reports, 100(2), 126–130 retrievd from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1424733/pdf/pubhealthrep00100-0016.pdf. Accessed 17 Mar 2020.

Egorov, A. Y., & Szabo, A. (2013). The exercise paradox: an interactional model for a clearer conceptualization of exercise addiction. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 2(4), 199–208. https://doi.org/10.1556/jba.2.2013.4.2.

European Commission (2018). Special Eurobarometer 472. Wave EB88.4. Report: Sport and Physical Activity. Retrieved from: https://ec.europa.eu/commfrontoffice/publicopinion/index.cfm/survey/getsurveydetail/instruments/special/surveyky/2164. Accessed 17 Mar 2020.

Fattore, L., Melis, M., Fadda, P., & Fratta, W. (2014). Sex differences in addictive disorders. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology, 35(3), 272–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yfrne.2014.04.003.

Griffiths, M. D. (1997). Exercise addiction: a case study. Addiction Research, 5(2), 161–168. https://doi.org/10.3109/16066359709005257.

Griffiths, M. D. (2005). A ‘components’ model of addiction within a biopsychosocial framework. Journal of Substance Use, 10(4), 191–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/14659890500114359.

Hausenblas, H. A., & Downs, D. S. (2002). How much is too much? The development and validation of the Exercise Dependence Scale. Psychology & Health, 17(4), 387–404. https://doi.org/10.1080/0887044022000004894.

Hausenblas, H. A., Schreiber, K., & Smoliga, J. M. (2017). Addiction to exercise. BMJ, j1745. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j1745.

Kotbagi, G., Muller, I., Romo, L., & Kern, L. (2014). Pratique problématique d’exercice physique: un cas clinique. Annales Médico-Psychologiques, Revue Psychiatrique, 172(10), 883–887. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amp.2014.10.011.

Lejoyeux, M., Avril, M., Richoux, C., Embouazza, H., & Nivoli, F. (2008). Prevalence of exercise dependence and other behavioral addictions among clients of a Parisian fitness room. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 49(4), 353–358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2007.12.005.

Maraz, A., Király, O., & Demetrovics, Z. (2015). Commentary on: Are we overpathologizing everyday life? A tenable blueprint for behavioral addiction research. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 4(3), 151–154. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.4.2015.026.

Monók, K., Berczik, K., Urbán, R., Szabo, A., Griffiths, M. D., Farkas, J., et al. (2012). Psychometric properties and concurrent validity of two exercise addiction measures: a population wide study. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 13(6), 739–746. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2012.06.003.

Schreiber, K., & Hausenblas, H. A. (2015). The truth about exercise addiction: Understanding the dark side of thinspiration. Lanham, MD, USA: Rowman & Littlefield.

Szabo, A. (2010). Addiction to exercise: a symptom or a disorder? New York: Nova Science.

Szabo, A. (2018). Addiction, passion, or confusion? New theoretical insights on exercise addiction research from the case study of a female body builder. Europe’s Journal of Psychology, 14(2), 296–316. https://doi.org/10.5964/ejop.v14i2.1545.

Szabo, A., & Kovacsik, R. (2019). When passion appears, exercise addiction disappears. Swiss Journal of Psychology, 78(3-4), 137–142. https://doi.org/10.1024/1421-0185/a000228.

Szabo, A., De La Vega, R., Ruiz-Barquín, R., & Rivera, O. (2013). Exercise addiction in Spanish athletes: investigation of the roles of gender, social context and level of involvement. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 2(4), 249–252. https://doi.org/10.1556/jba.2.2013.4.9.

Szabo, A., Griffiths, M. D., de la Vega Marcos, R. D., Mervó, B., & Demetrovics, Z. (2015). Methodological and conceptual limitations in exercise addiction research. The Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine, 88(3), 303–308.

Terry, A., Szabo, A., & Griffiths, M. (2004). The exercise addiction inventory: a new brief screening tool. Addiction Research and Theory, 12, 489–499. https://doi.org/10.1080/16066350310001637363.

Veale, D. (1995). Does primary exercise dependence really exist? In J. Annett, B. Cripps, & H. Steinberg (Eds.), Exercise addiction: motivation for participation in sport and exercise (pp. 1–5). Leicester: British Psychological Society.

Worldmeters.com (2019). U.K. Population (Live). Retrieved from: https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/uk-population/. Accessed 17 Mar 2020.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Eötvös Loránd University (ELTE).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics

The current study uses publicly available data, which is not subject to ethical clearance.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

All the listed web addresses were active on November 23, 2019

Case 1 https://www.theguardian.com/society/2002/sep/18/health.lifeandhealth

Case 2-4 https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2007/dec/04/healthandwellbeing.health

Case 5 https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB118277761367847006

Case 6 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1SVh-YOh3uw

Case 7-8 https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052748703439504576116083514534672

Case 9 https://lifeinsight.co.uk/2011/09/how-i-became-an-exercise-addict/

Case 10 https://www.prevention.com/life/a20435802/what-is-exercise-addiction/

Case 11 https://www.katyhaldiman.com/blog/tales-of-an-exercise-addict-with-autoimmune-disease

Case 12 https://www.runningwithspoons.com/2013/03/12/guest-post-overcoming-exercise-addiction/

Case 13 https://eu.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2013/05/06/mika-brzezinski-eating-disorders/2126465/

Case 14-15 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ne4pJ9QZQMM

Case 16 https://www.everydayhealth.com/news/addicted-exercise-carries-story/

Case 17-20 https://www.self.com/story/how-to-know-addicted-to-exercise

Case 21 https://www.thefix.com/content/biggest-loser-or-biggest-addict

Case 22 http://katalysthealthblog.com/from-exercise-addict-to-fitness-lover/

Case 23 https://www.wired.com/2014/10/my-strava-problem/

Case 25 https://hellogiggles.com/news/exercise-addiction/

Case 26 https://jessicapatay.com/?p=457

Case 28 https://www.runnersworld.com/women/a20800575/are-you-addicted-to-running/

Case 29 https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2015/mar/07/fitness-addiction-ill-scarlett-thomas

Case 30 https://www.theodysseyonline.com/self-diagnosed-exercise-addict

Case 31 https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/to-your-health/wp/2015/05/11/a-fitbit-fanatics-cry-for-help/

Case 32 https://greatist.com/connect/exercise-addiction-recovery#1

Case 34 https://www.thehealthymaven.com/exercise-addiction/

Case 35-36 https://www.thehealthymaven.com/exercise-addiction/

Case 37 https://www.todaysdietitian.com/newarchives/0916p62.shtml

Case 38 https://emilyfonnesbeck.com/returning-to-exercise-after-exercise-addiction-andor-disordered-eating/

Case 39-41 https://blonyx.com/blogs/blonyx-blog/5-signs-youre-addicted-to-working-out

Case 42 https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/confessions-of-a-midlife-fitness-addict-g9vn6wpnwh7

Case 43-44 https://www.tfflifestyle.com/tff036/

Case 45 https://www.thefinder.com.sg/healthy-living/fitness/true-story-i-was-exercise-addict/

Case 50-51 https://edition.cnn.com/2017/05/09/health/exercise-addiction-explainer/index.html

Case 53 https://www.refinery29.com/en-gb/exercise-addiction-symptoms

Case 55 https://psmag.com/social-justice/seduction-addiction-runners-confession-75187

Case 56-58 http://emilyanneswanson.com/exercise-addiction-beauty-christ-podcast/

Case 60 https://www.hellospoonful.com/blog/2017/12/22/10000-steps-fitbit-obessed/

Case 61 https://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/blog/what-i-learned-year-off-exercise

Case 62 https://metro.co.uk/2017/10/30/how-to-tell-when-going-to-the-gym-turns-into-an-addiction-7037953/

Case 63 https://www.esquire.com/lifestyle/health/a55197/exercise-bulimia/

Case 64-65 https://counseling.northwestern.edu/blog/exercise-addiction-intervention/

Case 68 https://www.independent.ie/life/are-you-addicted-to-exercise-37161261.html

Case 69 https://patient.info/news-and-features/how-to-spot-the-signs-of-an-exercise-addiction

Case 70-71 https://www.shape.com/lifestyle/mind-and-body/exercise-addiction-signs-treatment-recovery

Case 72 https://www.wellandgood.com/good-sweat/what-to-know-about-exercise-addiction/

Case 73 https://cfe.keltyeatingdisorders.ca/news/i-was-addicted-exercise-personal-story

Case 74 https://jennamayefitness.com/exercise-addiction-when-a-healthy-habit-goes-sideways/

Case 75 https://www.thecabinsydney.com.au/blog/exercise-addiction-when-exercise-becomes-unhealthy/

Case 77 https://www.thehealthy.com/exercise/fitness-addiction/

Case 78 https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/vba4dx/my-gamer-brain-is-addicted-to-the-peloton-exercise-bike

Case 80 https://www.naturally-nina.com/recovery/2018/5/31/exercise-in-eating-disorder-recovery

Case 83 https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/mbmv53/i-thought-running-was-a-release-it-was-really-an-addiction

Case 84 https://www.bucketlisttummy.com/how-i-overcame-exercise-addiction/

Case 85 https://www.beateatingdisorders.org.uk/your-stories/recovery/exercise-double-edged-sword

Case 86 https://exerciseright.com.au/how-i-overcame-exercise-addiction/

Case 90 https://www.balancedpursuits.com/episodes/stephanie-dankelson

Case 92 https://qz.com/quartzy/1595689/how-to-beat-a-marathon-training-addiction/

Case 95 https://ownitbabe.ca/i-didnt-work-out-for-a-year-and-here-is-what-happened/

Case 97 https://www.professorshouse.com/exercise-addiction/

Case 98 http://www.exercise-addiction.com/2014/09/09/lies-really-exercised-excessively/

Case 99-100 https://www.fitnessmagazine.com/health/conditions/exercise-addiction/

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Juwono, I.D., Szabo, A. 100 Cases of Exercise Addiction: More Evidence for a Widely Researched but Rarely Identified Dysfunction. Int J Ment Health Addiction 19, 1799–1811 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-020-00264-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-020-00264-6