Abstract

Understanding risk and protective factors associated with Internet Gaming Disorder (IGD) has been highlighted as a research priority by the American Psychiatric Association, (2013). The present study focused on the potential IGD risk effect of anxiety and the buffering role of family cohesion on this association. A sample of emerging adults all of whom were massively multiplayer online (MMO) gamers (18–29 years) residing in Australia were assessed longitudinally (face-to-face: N = 61, Mage = 23.02 years, SD = 3.43) and cross-sectionally (online: N = 64, Mage = 23.34 years, SD = 3.39). IGD symptoms were assessed using the nine-item Internet Gaming Disorder Scale-Short Form (IGDS-SF9; Pontes & Griffiths Computers in Human Behavior, 45, 137–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.12.006, 2015). The Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI; Beck and Steer, 1990) and the balanced family cohesion scale (BFC; Olson Journal of Marital & Family Therapy, 3(1) 64–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0606.2009.00175.x, 2011) were applied to assess anxiety and BFC levels, respectively. Linear regressions and moderation analyses confirmed that anxiety increased IGD risk and that BFC weakened the anxiety-related IGD risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

Video games refer to any interactive games that are available to play on a number of different formats (e.g., arcade machines, gaming consoles, personal computers, tablets, smartphones, etc.) and played in a variety of modes (e.g., single player, online multiplayer, local co-op) and genres (e.g., action, adventure, strategy). Gaming has been shown to have positive effects in a wide range of areas (considering the individual’s general adaptation) including learning performance (Green and Bavelier 2012; Green et al. 2010), prosocial behavior (Greitemeyer and Osswald 2010; Gentile et al. 2009), mood regulation (Bowman and Tamborini 2012; Russoniello et al. 2009), and cognitive abilities (e.g., visual short term memory; Boot et al. 2008). However, excessive video gaming (both online and offline) has been associated with increased experiences of loneliness (Lemmens et al. 2011; Caplan et al. 2009), aggression (Kim et al. 2008; Caplan et al. 2009), depression (Caplan et al. 2009; Wei et al. 2012), social anxiety (Lee and Leeson 2015; Lo et al. 2005) and low self-esteem (Lemmens et al. 2011), as well as having positive applications in the health field (Griffiths et al. 2017). These associations may be explained using the Compensatory Internet Use hypothesis, which assumes that individuals who are less psychologically resilient are more likely to turn to online applications (i.e., video games) to compensate for their difficulties offline. For example, individuals who have fears regarding negative evaluation and difficulties with offline social settings may rely on the online gaming environment for more accessible social communication, as a less distressing environment (Valkenburg and Peter 2009, 2013). Therefore, online gaming can be a positive activity for some, and problematic for others, particularly vulnerable populations. With this understanding of individual factors as well as shared addictive processes (Griffiths 2005a), Internet Gaming Disorder (IGD) was introduced as a potential disorder for further study in the latest (fifth) edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013).

IGD has been described as the relentless use of online videogames (generally with other players) that causes significant distress to the user (APA 2013). Similarities between IGD and other forms of addictions have been highlighted. More specifically, it has been suggested that IGD comprises common addiction components (Griffiths et al. 2014) such as mood modification (i.e., the way the object of addiction is used to modify the user’s mood), tolerance (i.e., the gradual building-up of resistance resulting in the need to engage more with the object of addiction), withdrawal symptoms (i.e., negative experiences when the object of the addiction is not present), conflict (compromising of all other things in the individual’s life such as educational/occupational duties, relationships, etc.), and relapse (i.e., reverting back to the addiction after a period of abstinence) (APA 2013; Anderson et al. 2016).

Several factors have been found to enhance IGD vulnerability. Indicatively, online games with a higher risk of developing IGD appear to share specific characteristics such as competing groups, teamwork, social communication, successive challenges, and accessibility to online games (APA 2013). Furthermore, comorbid psychopathological manifestations including attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), major depressive disorder (MDD), and neglecting of one’s health have all been associated with IGD (APA 2013). Despite the significant progress in the field, further research considering risk and protective factors of IGD has been recommended (APA 2013). To further this aim, the present study explores the possible risk effect of anxiety and the possible protective effect of family cohesion experiences on the IGD risk of more anxious individuals.

Massively Multiplayer Online Games

Research has shown that not all players of online games are equally at-risk in developing IGD, which is due in part to the diverse range of game types available (Kuss and Griffiths 2012). One type, massively multiplayer online (MMO) games, are games in which players can interact with each other simultaneously, as they are connected via the online medium to a large player base, which offers opportunity for competitive and cooperative goals that can be both challenging and immersive (Steinkuehler and Williams 2006; Lee et al. 2015). In this context, MMOs require the development of an online character (avatar) through which the player interacts with both the virtual world and other players (Elliot et al. 2012). Research has consistently demonstrated excessive online use behaviors among MMO players and higher rates of IGD prevalence compared to players of other game genres (Caplan et al. 2009; Müller et al. 2014; Stavropoulos et al. 2016). More specifically, MMO players have been found to play longer, and exhibit irritability when not able to play (Berle et al. 2015), as well as lower self-regulation, increased impulsivity, and reduced agreeableness (Collins et al. 2012). These traits have been closely associated with other forms of addiction (Tayeebi et al. 2013), indicating that MMO players are a specific risk population. Based on this prior research, the present study focuses on MMO players during the significant (from a developmental perspective) and concurrently understudied period of emergent adulthood (Kuss and Griffiths 2012).

Emergent Adulthood

The age group of emergent adulthood is broadly defined as the 18–29 year age group in industrialized countries (Arnett 2000; Arnett et al. 2014). Arnett (2000) suggested that emergent adulthood is a time for change and discovery and is an important age range for scholarly attention. Simultaneously, emergent adulthood has been characterized as a critical period for the development of addictions more generally (Stone et al. 2012), and online-related addictions more particularly (Sussman and Arnett 2014). In Australia (where the present study was carried out), the vast majority of gamers are emergent adults, who typically play to relieve boredom and to have fun (Brand and Todhunter 2015). Interestingly, DSM-5 estimates the prevalence of IGD to be between 12 and 20% during the initiation phase of emergent adulthood (APA 2013)—although this was based on non-nationally representative survey studies—while recreational online use increases during the same period (Yen et al. 2009). Finally, many types of addictive behaviors that were initiated during emergent adulthood have been shown to continue over the life course (Ashenhurst, Harden, Corbin, & Fromme, 2015). Despite clear evidence to suggest the importance of studying IGD symptoms during emergent adulthood, much remains unknown about IGD in this age group, because the international literature has disproportionally emphasized adolescence (Müller et al. 2015; Rehbein et al. 2015).

Risk and Resilience Framework (RRF)

Taking into consideration previous empirical findings and contemporary research recommendations, the present study adopts the Risk and Resilience Framework (RRF) in examining IGD among emergent adult MMO gamers (Anderson et al. 2016; Arnett et al. 2014; Arnett 2000). Resilience is defined as the combination of aspects and experience (i.e., protective factors and resources) that allow an individual to be unaffected by something problematic (Masten 2001). In contrast, risk is defined as involving aspects and experiences of individuals that make them susceptible to developing problematic disorders and behaviors (Grewirtz and Edleson 2007). In this context, the RRF posits that behaviors constantly vary on a continuum because of the interplay between developmental (age-related), individual (person-related), and contextual risk and protective factors (Masten 2014). In the present study, risk and RRF are used to explore IGD risk factors at the individual level (e.g., anxiety) and IGD resilience factors at the contextual level (e.g., family cohesion).

Anxiety

A significant relationship between anxiety and addictive behaviors, and technological addictions in particular, has been repeatedly demonstrated (Andreassen et al. 2016; Buckner and Schmidt 2009; Cooper et al. 2014; Essau et al. 2014; Lee and Stapinski 2012; Parhami et al. 2014; Sareen et al. 2006; Van Der Maas 2016). Furthermore, anxiety-related factors such as sensitivity to stress, perceived uncontrollability, and avoidance have also been shown to be associated with addiction severity (Forsyth et al. 2003). Nevertheless, the association between anxiety and addiction is considered bidirectional (Kushner et al. 2000). Anxiety and addictive behaviors can both initiate the other, and anxiety can contribute to the maintenance of, and relapse to an addictive behavior (Dalbudak et al. 2014). This has broadly been explained on the basis of addictive behaviors (such as IGD) providing immediate gratification and relief from anxiety, and thus functioning as maladaptive anxiety addressing mechanisms (Douglas et al. 2008; Griffiths 2005a, b; Griffiths et al. 2016; Marlatt and Donovan 2005; Mehroof and Griffiths 2010). Along this line, Caplan (2002) suggests that social anxiety predicts preference for online social interactions and leads to negative outcomes associated with problematic Internet use. This is in consensus with several studies suggesting an association between anxiety manifestations and excessive Internet use (Cole and Hooley 2013; Lee and Leeson 2015; Lo et al. 2005). Despite these few studies, there is generally a dearth of specialized (longitudinal) research emphasizing on potential buffers (i.e., protective factors) of anxiety’s effect on IGD. The present study therefore contributes to the field by exploring the potential protective role of family cohesion in both a cross-sectional and longitudinal manner.

Family Cohesion

In addition to anxiety, contextual factors have been implicated as being critical for the development of behavior in general (Cicchetti and Toth 2009), addictions in general (Griffiths 2005a, b), and technological addictions in particular (Douglas et al. 2008). More specifically, IGD-related studies have highlighted the need to pay equal attention to individual, cultural and online contexts (Kuss 2013). In that line, family contextual factors including parenting attitudes, family communication, and cohesion have been found to act protectively for excessive Internet use, whereas others, such as exposure to family conflicts, have been shown to increase it (Park et al. 2008). In this context, the significance of family cohesion has been illustrated for understanding addictive behaviors (Reeb et al. 2015). Family cohesion is described as the “emotional bonding among family members and the feeling of closeness that is expressed by feelings of belonging and acceptance within the family” (Johnson et al. 2001, p. 306). Cohesive families appear to function in a number of ways that may reduce addictive behaviors (i.e., binge drinking and smoking initiation; Rajesh et al. 2015; Solloski et al. 2015). In particular, cohesive families appear likely to decrease IGD escaping motives (i.e., individuals may not abscond to the virtual world due to their satisfying family context). Furthermore, such families may positively moderate other external stressors (i.e., peer issues), that could precipitate IGD behaviors, by providing a place of belonging, and a safe outlet for relieving tension (Rajesh et al. 2015; Solloski et al. 2015). This is in consensus with literature indicating family cohesion to have a buffering role in the associations between discomfort and distress and psychopathological behaviors, such as post-traumatic stress disorder (Farrell et al. 1995; Ibanez et al. 2015; Kaur and Kearney 2013). Subsequently, one might assume that higher levels of family cohesion moderate (i.e., buffer) IGD risk for more anxious individuals. The rationale for this hypothesis is twofold. Firstly, adaptive emotion regulation strategies through communication and sharing are promoted in more cohesive families (Li and Warner 2015) and therefore, individuals may have less urge to abscond online. Secondly, family cohesion has been related to greater connectedness and, as expected, is inversely related to neglect (Manzi et al. 2006; Wark et al. 2003). It therefore follows that a strong family base could reduce IGD risk. The present study is (to the best of the authors’ knowledge) the first that aims to assess this hypothesis.

The Present Study

The present study utilizes the RRF to explore the IGD risk effect of anxiety (as a factor related to the gamer) and the potential buffering effect of family cohesion on this association (as a moderating factor related to the gamer’s context). More specifically, a combination of cross-sectional and longitudinal data of Australian MMO gamers, aged 18–29 years is examined to address the following two hypotheses:

-

H1: Based on the available literature, it was hypothesized that higher anxiety symptoms would function (both cross-sectionally and longitudinally) as an IGD risk factor (i.e., individuals with higher anxiety levels will report higher IGD scores; Ahmadi et al., 2014; Dalbudak et al. 2014).

-

H2: It was hypothesized that higher levels of family cohesion would buffer (i.e., negatively moderate) the effect of anxiety on IGD symptoms over time (Kaur & Kearney 2013; Ibanez et al. 2015; Johnson et al. 2001; Priest & Denton, 2012).

Method

Participants

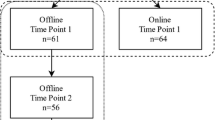

Participants involved in the cross-sectional (online and face-to-face) component of the present study were 125 emerging adultsFootnote 1 (Mage = 23.34, SD = 3.29, Minage = 18, Maxage = 29, Males = 49, 77.6%). Additionally, 61 participants were involved in the longitudinal (face-to-face) component (Mage = 23.34, SD = 3.39, Minage = 18, Maxage = 29, Males = 49, 77.6%). To ensure there were no significant differences between the cross-sectional and longitudinal participants on each of the variables, independent samples t tests and chi-squared analyses were conducted. No significant differences were found.Footnote 2 Time point 1 (T1), Time point 2 (T2) and Time Point 3 (T3) (longitudinal data) were used to assess the longitudinal part of Hypothesis 1 and Hypothesis 2 related to over time effects.Footnote 3 The estimated maximum sampling errors with a size of 125 (cross-sectional sample) and a size of 61 (longitudinal sample) are 8.77 and 12.55% (Z = 1.96, confidence level 95%) respectively. Demographic characteristics of the sample are listed in Table 1. For sample collection process see Fig. 1.

Measures

Internet Gaming Disorder Scale–Short Form 9 (IGDS-SF9)

Pontes and Griffiths’ (2015) IGS-SF9 includes nine items that assess the degree of Internet Gaming Disorder (IGD) symptoms. The IGDS-SF9 is based on the nine criteria for IGD outlined in the DSM-5 (APA 2013). Participants were asked to respond on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Never) to 5 (Very often) concerning their gaming behaviors (e.g., “Do you feel more irritability, anxiety or even sadness when you try to either reduce or stop your gaming activity?”). The score derived is a composite score, 9 (minimal IGD symptoms) to 45 (maximum IGD symptoms). The instrument demonstrated high Internal reliability (Cronbach α = .92) in the present study.

Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI)

The Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) is a 21-item scale used to assess participants’ anxiety (Beck and Steer 1990). Participants were asked to indicate how much a symptom “bothered” them in the past month (e.g., “Feeling hot”), ranging from 1 (Not at all) to 4 (Severely). Total scores were generated by summing all items, resulting in a range from 21(lower severity) to 84 (higher severity). Higher and lower scores indicate higher and lower severity of anxiety symptoms respectively. In the present study, internal consistency was excellent (Cronbach α = .95).

Balanced Family Cohesion Subscale

To assess family cohesion, and in consensus with previous studies (Jin 2015), the Balanced Family Cohesion Subscale of the Family Adaptability and Cohesion Evaluation Scale-FACES IV (Olson 2011) was used. The scale comprised of seven items, with participants required to answer questions that refer to the balance (e.g., connected without being emotionally disengaged and enmeshed) connectedness with their family members (e.g., “Although family members have individual interests, they still participate in family activities”). Participants were required to respond on a scale ranging from 1 (Never or definitely) to 5 (Strongly agree), items’ scores were added resulting to a range of 7 to 35. Higher scores indicate higher levels of balanced family cohesion and lower scores indicate lower levels of balanced family cohesion. In the present study the scale’s internal consistency was considered good to excellent (Cronbach α = .89).

Procedure

The project was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the authors’ university. Participants were recruited from the general community (including staff and students of the university) using traditional (i.e., information flyers) and electronic (i.e., email, social media) advertising methods.Footnote 4 The longitudinal sample was collected face-to-face over a three-month period between June 2016 and September 2016. Mutually agreed data collection appointments (25–35 min) were arranged with participants by a trained research team of five undergraduate students and two postgraduate students. No compensation was provided to the participants.

Online collection took place over a 1-month period (June 1, 2016 and July 1, 2016). Eligible individuals interested in participating and unable or unwilling to attend face-to-face testing sessions were invited to register with the study via a Survey-Monkey link available on MMO websites and forums. Individuals that chose to participate online were provided with a brief description of the study (i.e., methods, aims, conditions) and directed to click a button to provide informed consent (i.e., digitally sign).

Statistical Analysis

To assess H1, two linear regression analyses (one cross-sectional and one longitudinal) were conducted to determine if anxiety was an IGD risk factor. To assess H2, a moderation analysis was conducted via Process software (Hayes 2013) to determine if the interaction between anxiety and balanced family cohesion positively moderated (buffered) IGD symptoms. The longitudinal data were used to explore this relationship following relevant literature recommendations, which suggest longitudinal data is required to support causative associations (Winer et al. 2016). In accordance with these suggestions, participants’ anxiety scores at T1 were entered as the independent variable, balanced family cohesion at T2 was entered as the moderator, and IGD at T3 was used as the outcome variable. Finally, the Johnson Neyman (J–N) technique was applied to derive regions of significance (i.e., points of transition) of the moderation effect of balanced family cohesion on the association between anxiety and IGD symptoms (Preacher et al. 2007).

Results

The analyses’ assumptions, descriptive statistics and inter-correlations between the examined variables were assessed before calculating the results. To dimensionally assess (on a continuum from minimum to maximum) the association between anxiety and IGD symptoms H1, a linear regression analysis was first conducted on the cross-sectional data. More specifically, IGD symptoms were inserted as the dependent variable and anxiety was inserted as an independent variable. The effect of anxiety accounted for a significant 23.6% of the IGD variance (R2 = .24, F(1, 120) = 36.98, p < .001). According to the regression coefficient, one-unit increase in anxiety predicted a .32 increase in IGD scores (b = .32, SE(b) = .05, β = .49, p < .001).

The linear regression model described above was repeated using the longitudinal data. IGD symptoms assessed at T3 were inserted as the dependent variable, and anxiety at T1 as the independent variable. Anxiety at T1 accounted for a significant 8.9% of the variance in IGD symptoms at T3, R2 = .09, F(1, 56) = 5.48, p = .023. More specifically, one-unit of increase in anxiety at T1 predicted .16 of increase in IGD symptoms at T3 (b = .16, SE (b) = .07, β = 30, t = 2.34, p < .05).

To address H2, a moderation analysis was conducted adopting the methodology recommended by Hayes (2013). The model examined the moderating (buffering) effect of balanced family cohesion (Moderator) at T2 on the association between anxiety (IV) at T1 and IGD (DV) symptoms at T3. The model estimated the following:

IGD T3 = a + b1 anxiety T1 + b2 balanced family cohesion T2 + b3 [anxiety T1 × balanced family cohesion T2];

Findings indicated that the full model accounted for 17.88% of variance in IGD at T3. The slope of the regression line for the overall model was significant (F(3, 54) = 3.92, p = .01). An inspection of the interaction coefficient indicated that anxiety at T1 and balanced family cohesion at T2 significantly interacted (protective effect) in predicting IGD scores at T3, b = − .04, t(54) = −2.30, p = .03. Findings indicated that when an individual presented concurrently with a higher point (than the intercept) in anxiety at T1 and a higher point in balanced family cohesion at T2, then IGD symptoms at T3 reduce by .04. A visual representation of this buffering/protective effect is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Finally, the Johnson Neyman (J–N) technique was applied to derive regions of significance (points of transition) of the moderation effect in the sample (Preacher et al. 2007). Findings demonstrated that the buffering effect of balanced family cohesion at T2 on the association between anxiety at T1 and IGD at T3, started from the minimum values of the moderator and had a ceiling point for values of balanced family cohesion exceeding 29.74. This means that after this point, the moderation/buffering effect of balanced family cohesion at T2 on the association between anxiety at T1 and IGD at T3 had reached its maximum protective effect, b = .06, t(54) = .66, p = .51, (see Fig. 2).

Discussion

The present study used a Risk and Resilience Framework (RRF) approach to examine cross-sectional and over time variations (three points across a period of 3 months, 1 month apart each) of IGD behaviors among an Australian sample of MMO gamers, assessed online and/or face-to-face. More specifically, it investigated whether higher anxiety levels functioned as an IGD risk factor; and whether higher levels of family cohesion reduced IGD risk of more anxious individuals. Linear regression and moderation analyses demonstrated that higher anxiety associated with increased IGD behaviors both cross-sectionally and longitudinally. Furthermore, higher anxiety gamers were significantly less susceptible to IGD over time, when they experienced higher levels of family cohesion. These findings imply the need to consider the interplay between individual- and family-related factors when examining IGD and planning relevant prevention and intervention strategies.

Anxiety

Using the RRF (Masten 2014), anxiety was shown to be a factor (related to the player) that increased IGD risk. More specifically, results suggested that emergent adult MMO players who reported higher anxiety were inclined to have higher IGD scores. This is in consensus with previous research indicating the role of anxiety as a risk factor for addictions in general (Buckner and Schmidt 2009; Cooper et al. 2014; Parhami et al. 2014; Sareen et al. 2006; Van Der Maas 2016), and for online-related addictive behaviors in particular (Andreassen et al. 2016; Lee and Stapinski 2012).

It is likely that excessive use of online games may relieve symptoms of anxiety (Mehroof and Griffiths 2010). This explanation is in accord with the Compensatory Internet Use hypothesis, which suggests that individuals who are less psychologically resilient may turn to online communications (e.g., via online games) to compensate for their difficulties offline (i.e. anxiety; Valkenburg and Peter 2009, 2013). Applying this to the present study, it would mean that participants with higher anxiety levels are more likely turn to online games to compensate for their real-world life difficulties, where they are more anxious, because this would provide relief from the thoughts or experiences that may precipitate and/or perpetuate their anxiety symptoms. Conceptually, there are several aspects of a person’s real life such as social interaction and fear of negative evaluation, which could act as anxiety triggers (i.e., stress-related issues) and appear not to be evident whilst gaming (Mehroof & Griffiths 2010). In this context, the Compensatory Internet Use Hypothesis for explaining the IGD risk of more anxious gamers aligns with an extensive body of literature, which suggests that addictive behaviors (in general) provide immediate gratification and relief from anxiety and distress (Akin and İskender 2011; Douglas et al. 2008; Griffiths 2005a, b; Griffiths et al. 2016).

Family Cohesion as a Buffer of the IGD Risk Effect of Anxiety

Interestingly, the present study demonstrated that more anxious emergent adults, who play MMOs and experienced higher levels of family cohesion were at lower IGD risk (than their equally anxious co-players, who reported lower family cohesion levels). Additionally, a ceiling effect was found for high scores of family cohesion, meaning that after a specific point, higher levels of family cohesion would not further reduce the IGD risk of more anxious gamers. Along this line, the buffering effect that family cohesion had on the association between anxiety and IGD was substantially stronger when family cohesion increased between low and average levels. To the best of the author’s knowledge, this is the first study that has examined the potential protective effect of higher family cohesion for more anxious gamers. Nevertheless, the findings were in consensus with previous research suggesting that family cohesion may have a significant role in preventing the development of addictions (Solloski et al. 2015; Rajesh et al. 2015; Manzi et al. 2006; Wark et al. 2003; Li and Warner 2015). There are two potential reasons why this might be the case. Firstly, adaptive emotion regulation strategies via communication and sharing are promoted in more cohesive families (Li and Warner 2015), and therefore, individuals may have less urge to abscond online (via excessive gaming). Secondly, family cohesion has been related to increased connectedness and less neglect (Manzi et al. 2006; Wark et al. 2003). This may mean that individual players would be more likely to talk and gain relief regarding issues causing them anxiety within more cohesive families. These options could deter more anxious gamers from the excessive use of online games to address their anxiety-related discomfort and distress.

However, reinforcing family cohesion is not a panacea for IGD in more anxious gamers. The ceiling effect indicated that higher family cohesion positively moderates the IGD risk until a specific point and can be more effective when raising the family cohesion levels from low to average. This could be interpreted as the result of family cohesion levels not exclusively moderating the IGD risk of more anxious gamers (Anderson et al. 2016). Other factors, such as game-related features (i.e., avatar graphs, gaming structure) may also contribute and/or accommodate gaming over-involvement of more anxious individuals, and their effect could be more significant when family cohesion is experienced (Anderson et al. 2016). Future research should build upon these findings by more clearly delineating the potential basis of family cohesion’s positive role and providing guidelines for more effective IGD prevention and treatment efforts.

Limitations, Implications, Future Research and Conclusions

The present study has several strengths including (i) a concurrent examination of online and face-to-face participants; (ii) a combination of cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses; (iii) an emphasis on an under-researched high risk population for IGD (emergent adult MMO gamers), and (iv) a focus on both individual- and contextual-related factors, as well as their interplay in relation to IGD.

However, there are several limitations that need to be considered. Firstly, IGD was assessed by focusing on a specific group of online gaming genres. There are multiple online gaming genres, and therefore characteristics of those who play them may vary accordingly. Secondly, the sample size was relatively small (N = 125), suggesting that limitations may exist when extrapolating the results. Thirdly, the longitudinal design applied referred to a relatively short timeframe. Fourth, the present study used self-report measures that may have affected reliability because participant responses can be influenced by mood and situational factors at the time when the assessment occurred (Smith & Handler, 2007). Finally, different directions of the causal relationships between the variables involved in the study could have been examined (i.e., low family cohesion mediated by anxiety on IGD risk).

Within the context of the aforementioned limitations, the findings have several important clinical implications. Considering IGD prevention, the findings suggest that individuals who report higher anxiety need to be prioritized, especially when they are situated in families with lower family cohesion levels. In relation to treatment directions, cognitive-behavior therapy may be useful to promote awareness in regard to the use of IGD as a potential maladaptive emotional compensation strategy. Furthermore, family therapy promoting higher family cohesion levels may prove beneficial in reducing IGD risk of higher anxiety players.

In line with these suggestions, the present study prompts several further research avenues within the IGD field. Future research should more deeply investigate the longitudinal interplay between individual (i.e. age, gender, societal, cultural background) and gaming-related factors (i.e. game genre, game structure, character development). Furthermore, increasing the length of the longitudinal design could greatly benefit knowledge considering time-related variations in the association between anxiety and IGD, and well as the anxiety-family cohesion interaction. Investigating other potential protective factors that reduce the association between anxiety and IGD may also add to the extant knowledge.

Notes

This study is a part of a wider project of the authors’ university that addresses the interplay between individual, gaming and proximal context factors in the development of Internet Gaming Disorder symptoms in emergent adults. Instruments used in the data include the: (i) Internet Gaming Disorder - Short Form 9 (9 items; Pontes & Griffiths, 2015); (ii) Beck Depression Inventory - second edition (21 items; Beck and Steer, 1990); (iii) Beck Anxiety Inventory (Beck & Steer, 1990); (iv) Hikikomori-Social Withdrawal Scale (5 items; Teo et al., 2015); (v) Attention Deficit Hyperactivity self-report scale (18 items; Kessler et al., 2005); (vi) Ten item personality inventory (Gosling, Rentfrow & Swann, 2003); (vii) The Balanced Family Cohesion Scale (Olson, 2011); (viii) Presence Questionnaire (10 items; Faiola, Newlon, Pfaff, & Smyslova, 2013); (ix); Online Flow Questionnaire (5 items; Chen Wigand & Nilan, 2000) (x) Self-Presence Questionnaire (Ratan & Hasler, 2010); (xi) Gaming-Contingent Self-Worth Scale (12 items; Beard & Wickham, 2016); and (xiii) a fitness tracker (Fitbit flex), assessing physical activity, for face-to-face data collection only.

To ensure that there were no significant differences between the online and face-to-face samples considering their demographic and Internet use characteristics, independent sample t-tests and chi-square analyses were conducted. Findings did not indicate any significant differences in regards to gender (x2 = .21, df = 1, p = .89), the age of the participants (t = −.54, df = 120, p = .59) and their years of internet use (t = 2.35, df = 122, p = .06). Therefore, online and face-to-face data (i.e., TP1) were combined (i.e., analyzed together) to investigate cross-sectional questions.

The longitudinal design was assessed for attrition. Assessments’ frequency for each participant varied within a range of 1–3 (Maverage = 2.57). Time Point 1 comprised 61 participants, Time Point 2 comprised 56 participants (8.20% attrition), and Time Point 3 comprised 43 participants (29.51% attrition). In line with literature recommendations, attrition, in relation to the studied variables, was assessed using Little’s Missing Completely At Random test (MCAR), which was insignificant (MCAR X2 = 1715.79, p = 1.00; Little & Rubin, 2014). In order to avoid list-wise deletion, which would reduce the sample’s power, maximum likelihood imputation (five times) of values was applied (Gold & Bentler, 2000).

In line with the approval received by the ethics committee of the participating university, the flyers: (i) indicated that participants were required to participate on three separate measurement occasions approximately 1 month apart; (ii) included an email address to contact the investigators; and (iii) clearly described the process and stages of the data collection (face-to-face and online). MMO and MMORPG players, aged between 18 and 29 years, interested in the study received the Plain Language Information Statement (PLIS). The PLIS clearly indicated that participation was voluntary and that participants could independently decide to withdraw from the study at any point. Individuals who choose to participate were required to provide informed consent.

References

Ahmadi, J., Amiri, A., Ghanizadeh, A., Khademalhosseini, M., Khademalhosseini, Z., Gholami, Z., & Sharifian, M. (2014). Prevalence of addiction to the internet, computer games, DVD and video and its relationship to anxiety and depression in a sample of Iranian high school students. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Behaviour Sciences, 8(2), 75–80 Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4105607/

Akin, A., & İskender, M. (2011). Internet addiction and depression, anxiety and stress. International Online Journal of Educational Sciences, 3(1), 138–148.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington: Author.

Anderson, E. L., Steen, E., & Stavropoulos, V. (2016). Internet use and problematic Internet use: a systematic review of longitudinal research trends in adolescence and emergent adulthood. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2016.1227716.

Andreassen, C. S., Billieuz, J., Griffiths, M. D., Kuss, D. J., Demetrovics, Z., Mazzoni, E., & Pallesen, S. (2016). The relationship between addictive use of social media and videogames and symptoms of psychiatric disorders: a large-scale cross sectional study. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 30(2), 252–262. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000160.

Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood. A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55(5), 469–480. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.5.469.

Arnett, J. J., Žukauskienė, R., & Sugimura, K. (2014). The new life stage of emerging adulthood at ages 18–29 years: implications for mental health. The Lancet Psychiatry, 1(7), 569–576. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(14)00080-7.

Ashenhurst, J. R., Harden, K. P., Corbin, W. R., & Formme, K. (2015). Trajectories of binge drinking and personality change across emerging adulthood. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 29(4), 978–991. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000116

Beard, C. L., & Wickham, R. E. (2016). Gaming-contingent self-worth, gaming motivation, and internet gaming disorder. Computers in Human Behavior, 61, 507–515. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.03.046

Beck, A. T., & Steer, R. A. (1990). Manual for the Beck anxiety inventory. San Antonio: Psychological Corporation.

Berle, D., Starcevic, V., Poter, G., & Fenech, P. (2015). Are some games associated with more life interference and psychopathology than other? Comparing massively multiplayer online role-playing games with other forms of video games. Australian Journal of Psychology, 67(2), 105–114. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajpy.12066.

Boot, W. R., Kramer, A. F., Simons, D. J., Fabiani, M., & Gratton, G. (2008). The effect of video game playing on attention memory and executive control. Acta Psychologica, 129(3), 387–398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2008.09.005.

Bowman, N. D., & Tamborini, R. (2012). Task demand and mood repair: the intervention potential of computer games. New Media & Society, 14(8), 1339–1357. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444812450426.

Brand, J. E., & Todhunter, S. (2015). Digital Australia 2016. Eveleigh: IGEA.

Buckner, J. D., & Schmidt, N. B. (2009). Understanding social anxiety as a risk for alcohol use disorders: fear of scrutiny, not social interaction fears, prospectively predicts alcohol use disorders. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 43(4), 477–483. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.04.012.

Caplan, S. E. (2002). Problematic internet use and psychosocial well-being: development of a theory-based cognitive-behavioral measurement instrument. Computers in Human Behavior, 18(5), 553–575. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0747-5632(02)00004-3.

Caplan, S., Williams, D., & Yee, N. (2009). Problematic Internet use and psychosocial well-being among MMO players. Computers in Human Behavior, 25(6), 1312–1319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2009.06.006.

Chen, H., Wigand, R. T., & Nilan, M. (2000). Exploring web users’ optimal flow experiences. Information Technology & People, 13(4), 263–281. https://doi.org/10.1108/09593840010359473

Cicchetti, D., & Toth, S. L. (2009). The past achievements and future promises of developmental psychopathology: the coming of age of a discipline. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 50(1–2), 16–25. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01979.x.

Cole, S. H., & Hooley, J. M. (2013). Clinical and personality correlates of MMO gaming: anxiety and absorption in problematic Internet use. Social Science Computer Review, 31(4), 424–435. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439312475280.

Collins, E., Freeman, J., & Chamarro-Premuzic, T. (2012). Personality traits associated with problematic and non-problematic massively multiplayer online role playing game use. Personality and Individual Differences, 52(2), 133–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.09.015.

Cooper, R., Hildebrandt, S., & Gerlach, A. L. (2014). Drinking motives in alcohol use disorder patients with and without social anxiety disorder. Anxiety, Stress and Coping, 27(1), 113–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2013.823482.

Dalbudak, E., Evren, C., Aldemir, S., & Evren, B. (2014). The severity of internet addiction risk and its relationship with the severity of borderline personality features, childhood traumas, dissociative experiences, depression and anxiety symptoms among Turkish university students. Psychiatry Research, 219(3), 577–582. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2014.02.032.

Douglas, A., Mills, J. E., Niang, M., Stepchenkova, S., Byun, S., Ruffini, C., et al. (2008). Internet addiction- meta-synthesis of qualitative research for the decade 1996–2006. Computers in Human Behavior, 24(6), 3027–3044. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2008.05.009.

Elliot, L., Golub, A., Ream, G., & Dunlap, E. (2012). Video game genre as a predictor of problem use. Cyberpsycology, Behavior and Social Networking, 15(3), 155–161. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2011.0387.

Essau, C. A., Lewinsohn, P. M., Olaya, B., & Seeley, J. R. (2014). Anxiety disorders in adolescents and psychosocial outcomes at age 30. Journal of Affective Disorders, 163, 125–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2013.12.033.

Faiola, A., Newlon, C., Pfaff, M., & Smyslova, O. (2013). Correlating the effects of flow and telepresence in virtual worlds: Enhancing our understanding of user behavior in game-based learning. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(3), 1113–1121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.10.003

Farrell, M. P., Barnes, G. M., & Banerjee, S. (1995). Family cohesion as a buffer against the effects of problem-drinking fathers on psychological distress, deviant behavior, and heavy drinking in adolescents. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 36(4), 377–385.

Forsyth, J. P., Parker, J. D., & Finlay, C. G. (2003). Anxiety sensitivity, controllability, and experiential avoidance and their relation to drug of choice and addiction severity in a residential sample of substance-abusing veterans. Addictive Behaviors, 28(5), 851–870. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-4603(02)00216-2.

Gentile, D. A., Anderson, C. A., Yukawa, S., Ihoei, N., Saleem, M., Ming, L. K., Shibuya, A., Liau, A. K., Khoo, A., Bushman, B. J., Huesmann, L. R., & Sakamoto, A. (2009). The effect of prosocial video games on prosocial behaviors: international evidence from correlational, longitudinal, and experimental studies. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 35(6), 752–763. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167209333045.

Gold, M. S., & Bentler, P. M. (2000). Treatments of missing data: A Monte Carlo comparison of RBHDI, iterative stochastic regression imputation, and expectation-maximization. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 7, 319–355. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0703

Green, C. S., & Bavelier, D. (2012). Learning, attention control and action video games. Current Biology, 22, 197–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2012.02.012.

Green, C. S., Li, R., & Bavelier, D. (2010). Perceptual leading during action playing video games. Topics in Cognitive Science, 2(2), 202–216. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1756-8765.2009.01054.x.

Greitemeyer, T., & Osswald, S. (2010). Effects of prosocial video games on prosocial behavior. Journal of Personality and Psychological Association, 92(2), 211–221. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016997.

Grewirtz, A. H., & Edleson, J. L. (2007). Young children’s exposure to intimate partner violence: towards a developmental risk and resilience framework for research and intervention. Journal of Family Violence, 22(3), 151–163. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-007-9065-3.

Griffiths, M. D. (2005a). A “components” model of addiction within a biopsychosocial framework. Journal of Substance Use, 10(4), 191–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/14659890500114359.

Griffiths, M. D. (2005b). The biopsychosocial approach to addiction. Psyke & Logos, 26(1), 9–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/14659890500114359.

Griffiths, M. D., King, D. L., & Demetrovics, Z. (2014). DSM-5 internet gaming disorder needs a unified approach to assessment. Neuropsychiatry, 4(1), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.2217/NPY.13.82.

Griffiths, M. D., Van Rooij, A. J., Kardefelt-Winther, D., Starcevic, V., Király, O., Pallesen, S., et al. (2016). Working towards an international consensus on criteria for assessing Internet Gaming Disorder: a critical commentary on Petry et al. (2014). Addiction, 111(1), 167–175. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13057.

Griffiths, M. D., Kuss, D. J., & Ortiz de Gortari, A. (2017). Videogames as therapy: an updated selective review of the medical and psychological literature. International Journal of Privacy and Health Information Management, 5(2), 71–96. https://doi.org/10.4018/IJPHIM.2017070105.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. New York: Guilford Press.

Ibanez, G. E., Dillion, F., Sanchez, M., Rosa, M., Tan, L., & Villar, M. E. (2015). Changes in family cohesion and acculturative stress among recent Latino immigrants. Journal of Ethnic Cultural Diversity in Social Work, 24(3), 219–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2013.845278.

Jin, B. (2015). Family cohesion and child functioning among South Korean immigrants in the US: The mediating role of Korean parent-child closeness and the moderating role of acculturation (Doctoral dissertation). New York: Syracuse University Retrieved from http://surface.syr.edu/etd.

Johnson, H. J., LaVoie, J. C., & Mahoney, M. (2001). Interparental conflict and family cohesion: predictors of loneliness, social anxiety and social avoidance in late adolescence. Journal of Adolescent Research, 16(3), 304–318. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558401163004.

Kaur, H., & Kearney, C. A. (2013). Ethnic identity, family cohesion, and symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder in maltreated youth. Journal of Aggression, 22(10), 1085–1095. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2013.845278

Kessler, R. C., Adler, L., Ames, M., Demler, O., Faraone, S., Hiripi, E. V. A., & Ustun, T. B. (2005). The world health organization adult ADHD self-report scale (ASRS): A short screening scale for use in the general population. Psychological Medicine, 35(02), 245–256. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291704002892.

Kim, E. J., Namkoong, K., Ku, T., & Kim, S. J. (2008). The relationship between online game addiction and aggression, self-control and narcissistic personality traits. European Psychiatry, 23(3), 212–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2007.10.010.

Kushner, M. G., Abrams, K., & Borchardt, C. (2000). The relationship between anxiety disorder and alcohol use disorders: a review of major perspective and findings. Clinical Psychology Review, 20(2), 149–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-7358(99)00027-6.

Kuss, D. J. (2013). Internet gaming addiction: current perspectives. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 6, 125–137. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S39476.

Kuss, D. J., & Griffiths, M. D. (2012). Online gaming addiction in children and adolescents: a review of empirical research. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 1(1), 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1556/JBA.1.2012.1.1.

Lee, B. W., & Leeson, P. R. N. M. (2015). Online gaming in the context of social anxiety. Psychology of Addictive Behavior, 29(2), 473–482. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000070.

Lee, B. W., & Stapinski, L. A. (2012). Seeking safety on the internet: relationship between social anxiety and problematic internet use. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 26(1), 197–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.11.001.

Lee, Z. W. Y., Cheung, C. M. K., & Chan, T. K. H. (2015). Massively multiplayer online game addiction: instrument development and validation. Information Management, 52(4), 413–430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2015.01.006.

Lemmens, J. S., Valkenburg, P. M., & Peter, J. (2011). Psychosocial causes and consequences of pathological gaming. Computers in Human Behavior, 27(1), 144–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2010.07.015.

Li, Y., & Warner, L. A. (2015). Parent-adolescent conflict, family cohesion, and self-esteem among Hispanic adolescents in immigrant families: a comparative analysis. Family Relations, 64(5), 579–591. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12158.

Little, R. J., & Rubin, D. B. (2014). Statistical analysis with missing data. Hoboken: Wiley.

Lo, S. K., Wang, C. C., & Fang, W. (2005). Physical interpersonal relationships and social anxiety among online game players. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 8(1), 15–20. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2005.8.15.

Manzi, C., Vignoles, V. L., Regalia, C., & Scabini, E. (2006). Cohesion and enmeshment revisited: differentiation, identity, and well-being in two European cultures. Journal of Marriage and Family, 68(3), 673–689. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00282.x.

Marlatt, G. A., & Donovan, D. M. (2005). Relapse prevention: maintenance strategies in the treatment of addictive behaviors (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

Masten, A. S. (2001). Ordinary magic. Resilience processes in development. American Psychologist, 56(3), 227–238. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.227.

Masten, A. S. (2014). Invited commentary: resilience and positive youth development frameworks in developmental science. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43(6), 1018–1024. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-014-0118-7.

Mehroof, M., & Griffiths, M. D. (2010). Online gaming addiction: the role of sensation seeking, self-control, neuroticism, aggression, state anxiety, and trait anxiety. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 13(3), 313–316. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2009.0229.

Müller, K. W., Beutel, M. E., Egloff, B., & Wölfling, K. (2014). Investigating risk factors for Internet gaming disorder: a comparison of patients with addictive gaming, pathological gamblers and healthy controls regarding the big five personality traits. European Addiction Research, 20(3), 129–136. https://doi.org/10.1159/000355832.

Müller, K. W., Janikian, M., Dreier, M., Wölfling, K., Beutel, M. E., Tzavara, C., Richardson, C., & Tsitsika, A. (2015). Regular gaming behaviour and internet gaming disorder in European adolescents: results from a cross-national representative survey of prevalence, predictors, and psychopathological correlates. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 24(5), 565–574. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-014-0611-2.

Olson, D. (2011). Faces IV and the circumplex model: validation study. Journal of Marital & Family Therapy, 3(1), 64–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0606.2009.00175.x.

Parhami, I., Mojtabai, R., Rosenthal, R. J., Afifi, T. O., & Fong, T. W. (2014). Gambling and the onset of comorbid mental disorders: a longitudinal study evaluating severity and specific symptoms. Journal of Psychiatric Practice, 20(3), 207–219. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.pra.0000450320.98988.7c.

Park, S. K., Kim, J. Y., & Cho, C. B. (2008). Prevalence of internet addiction and correlation with family factors among south Korean adolescents. Adolescence, 43(172), 895–909.

Pontes, H. M., & Griffiths, M. D. (2015). Measuring DSM-5 internet gaming disorder: development and validation of a short psychometric scale. Computers in Human Behavior, 45, 137–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.12.006.

Preacher, K. J., Rucker, D. D., & Hayes, A. F. (2007). Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 42(1), 185–227. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273170701341316.

Priest, J. B., & Denton, W. (2012). Anxiety disorders and Latinos. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 34(4), 557–575. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739986312459258

Rajesh, V., Diamond, P. M., Spitz, M. R., & Wilkinson, A. V. (2015). Smoking initiation among Mexican heritage youth and the role of family cohesion and conflict. Journal of Adolescent Health, 57(1), 24–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.01.021.

Ratan, R., & Hasler, B. S. (2010). Exploring self-presence in collaborative virtual teams. PsychNology Journal, 8(1), 11–31 Retrieved from https://scholars.opb.msu.edu/en/publications/exploring-self-presencein-collaborative-virtual-teams-2

Reeb, B. T., Chan, S. Y. S., Conger, K. J., Martin, M. J., Hollis, N. D., Serido, J., & Russell, S. T. (2015). Prospective effects of family cohesion on alcohol-related problems in adolescence: similarities and differences by race/ethnicity. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 44(10), 1941–1953. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-014-0250-4.

Rehbein, F., Kliem, S., Baier, D., Mößle, T., & Petry, N. M. (2015). Prevalence of internet gaming disorder in German adolescents: diagnostic contribution of the nice DSM-5 criteria in a state-wide representative sample. Addiction, 110(5), 842–851. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.12849.

Russoniello, C. V., O’Brien, K., & Parks, J. M. (2009). EEG, HRV and psychological correlates while playing bejeweled II: a randomized controlled study. Studies in Health Technology and information, 144, 189–192.

Sareen, J., Chartier, M., Paulus, M. P., & Stein, M. B. (2006). Illicit drug and anxiety disorders: findings from two community surveys. Psychiatry Research, 142(1), 11–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2006.01.009.

Smith, S. R., & Handler, L. (2007). The clinical assessment of child and adolescents. New York: Routledge.

Solloski, K. L., Monk, J. K., & Durtschi, J. A. (2015). Trajectories of early binge drinking: a function of family cohesion and peer use. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 42(1), 76–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmft.12111.

Stavropoulos, V., Kuss, D. J., Griffiths, M. D., & Motti-Stefanidi, F. (2016). A longitudinal study of adolescent internet addiction: the role of conscientiousness and class room hostility. Journal of Adolescent Research, 31(4), 442–473. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558415580163.

Steinkuehler, C. A., & Williams, D. (2006). Where everybody knows your screen name: online games as “third places”. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 11(4), 885–909. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2006.00300.x.

Stone, A. L., Becker, L. G., Huber, A. M., & Catalano, R. F. (2012). Review of risk and protective factors of substance use and problem use in emerging adulthood. Addictive Behaviors, 37(7), 747–775. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.02.014.

Sussman, S., & Arnett, J. J. (2014). Emerging adulthood: developmental period facilitative of the addictions. Evaluation & the Health Professions, 37(2), 147–155. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163278714521812.

Tayeebi, K., Abolghasemi, A., Alilu, M. M., & Monirpoor, N. (2013). The comparison of self-regulation and affective control in methamphetamine and narcotic addicts and non-addicts. International Journal of High Risk Behaviors & Addiction, 1(4), 172–177. https://doi.org/10.5812/ijhrba.8442.

Teo, A. R., Fetters, M. D., Stufflebam, K., Tateno, M., Balhara, Y., Choi, T. Y., & Kato, T. A. (2015). Identification of the hikikomori syndrome of social withdrawal: Psychosocial features and treatment preferences in four countries. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 61(1), 64–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764014535758

Valkenburg, P. M., & Petet, J. (2009). Social consequences of the internet for adolescents. Current Directions in Psychological Sciences, 18(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01595.x.

Valkenburg, P. M., & Petet, J. (2013). The differential susceptibility to media effect model. Journal of Communication, 63(2), 221–243. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12024.

Van Der Maas, M. (2016). Problem gambling, anxiety and poverty: an examination of the relationship between poor mental health and gambling problems across socio-economic status. International Gambling Studies, 16(2), 281–295. https://doi.org/10.1080/14459795.2016.1172651.

Wark, M. J., Kruczek, T., & Boley, A. (2003). Emotional neglect and family structure: impact on student functioning. Child Abuse & Neglect, 27(9), 1033–1043. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0145-2134(03)00162-5.

Wei, H. T., Chen, M. H., Huang, P. C., & Bai, Y. M. (2012). The association between online gaming depression: an internet survey. BMC Psychiatry, 12(1), 92. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-12-92.

Winer, E. S., Cervone, D., Bryant, J., McKinney, C., Liu, R. T., & Nadorff, M. R. (2016). Distinguishing mediational models and analyses in clinical psychology: atemporal associations do not imply causation. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 72(9), 947–955. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22298.

Yen, J. Y., Yen, C. F., Chen, C. S., Tang, T. C., & Ko, C. H. (2009). The association between adult ADHD symptoms and internet addiction among college students: the gender difference. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 12(2), 18–91. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2008.0113.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have any interests that could constitute a real, potential or apparent conflict of interest with respect to their involvement in the publication. The authors also declare that they do not have any financial or other relations (e.g. directorship, consultancy or speaker fee) with companies, trade associations, unions or groups (including civic associations and public interest groups) that may gain or lose financially from the results or conclusions in the study. Sources of funding are acknowledged.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of University’s Research Ethics Board and with the 1975 Helsinki Declaration.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Appendix

Appendix

Correlations and Descriptive Statistics

A Pearson correlational analysis demonstrated a significant positive relationship between anxiety and IGD symptoms in the cross-sectional data, r(122) = .49, p < .001. Associations among IGD at all time points, family cohesion at all time points, and anxiety at all times points, using Pearson correlation coefficients are presented in Table 2. Means and standard deviations are presented in Table.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Adams, B.L.M., Stavropoulos, V., Burleigh, T.L. et al. Internet Gaming Disorder Behaviors in Emergent Adulthood: a Pilot Study Examining the Interplay Between Anxiety and Family Cohesion. Int J Ment Health Addiction 17, 828–844 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-018-9873-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-018-9873-0