Abstract

The activity of play has been ever present in human history and the Internet has emerged as a playground increasingly populated by gamers. Research suggests that a minority of Internet game players experience symptoms traditionally associated with substance-related addictions, including mood modification, tolerance and salience. Because the current scientific knowledge of Internet gaming addiction is copious in scope and appears relatively complex, this literature review attempts to reduce this confusion by providing an innovative framework by which all the studies to date can be categorized. A total of 58 empirical studies were included in this literature review. Using the current empirical knowledge, it is argued that Internet gaming addiction follows a continuum, with antecedents in etiology and risk factors, through to the development of a “full-blown” addiction, followed by ramifications in terms of negative consequences and potential treatment. The results are evaluated in light of the emergent discrepancies in findings, and the consequent implications for future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

The activity of play has been ever present in human history. Playing games is pleasurable and entertaining, and it is a way of relaxation stepping out of the daily routine and enjoying something distinct from everyday life. In his cultural analysis of play, Huizinga (1938) refers to play as “a free activity (…) outside “ordinary” life as being “not serious”, but at the same time absorbing the player intensely and utterly. (…) It proceeds within its own proper boundaries of time and space according to fixed rules and in an orderly manner. It promotes the formation of social groupings which tend to surround themselves with secrecy and to stress their difference from the common world by disguise or other means” (Huizinga 1938, p. 13). Therefore, not only is play an enjoyable pastime activity, it is a social activity as well. It connects likeminded people, thereby fostering sociocultural protocols of behaviors associated with gameplay.

With the Internet, a new playground has emerged. In effect, the Internet offers a wide variety of games to play, which are distributed across a variety of game genres. These include (but are not restricted to) casual Browser Games (CBGs) such as DarkOrbit, First-Person or Ego-Shooters (FPSs) such as Counterstrike, Massively Multiplayer Online Role-Playing Games (MMORPGs) such as World of Warcraft (WoW), and Simulation Games (SGs) such as Second Life, to name but the most important. Furthermore, there exist hybrid forms, such as Massively Multiplayer Online Role-Playing First-Person Shooters (MMORPFPSs), such as Neocron, which combine distinct genres within one game. CBGs are played on an Internet browser and are free and easily accessible. FPSs are online tactics-shooters played from an ego-perspective in a 3D-game world. This is the game genre most frequently played in e-sports.

MMORPGs are played by hundreds of thousands of users throughout the world simultaneously. In-game, players frequently socialize in guildsFootnote 1 and cooperate in order to reach game-relevant goals. Moreover, they play roles by taking on virtual personae, so-called avatars, such as magicians or warriors. Finally, Simulation Games simulate real life in a metaverse where everything that can be done in actual life can be done in a virtual, second life as well. The broad appeal of these games is outlined by the NPD’s 2009 software sales ranking: The Sims 3 was sold most, followed by WoW’s Wrath of the Lich King (The NPD Group 2010). The next games in the ranking see an alteration between other versions of these two games, indicating that the public’s current preference is for MMORPGs and real life simulations. This preference may be explained by the fact that “(p)lay enables the exploration of that tissue boundary between fantasy and reality, between the real and the imagined, between the self and the other. In play we have license to explore, both our selves and our society. In play we investigate culture, but we also create it” (Silverstone 1999, p. 64). Therefore, the blurring of the boundaries between the real and the virtual appears particularly relevant for these two most frequently played game genres.

The latest software sale rankings demonstrate that Internet games attract many gamers. This appeal is even greater for a small minority of people who play excessively. Research suggests that this minority may experience symptoms traditionally associated with substance-related addictions, such as mood modification, tolerance, and behavioral salience (Hsu et al. 2009; Ko et al. 2009; Mehroof and Griffiths 2010; Wölfling et al. 2008; Young, 2009). In order to avoid potential conceptual confusion, this review will refer to the phenomenon as Internet gaming addiction, although researchers tend to use a variety of different conceptualizations. This topic will be addressed in more detail in the section on classification and assessment. Nonetheless, in the last few years, research on Internet gaming addiction has proliferated. A relatively large number of studies were published, addressing topics as diverse as classification, etiology, and phenomenology of this behavioral addiction. There have also been recent reviews on whether the concept of Internet gaming addiction is even a valid concept (e.g., Griffiths 2010a) but such debate is not the focus of this paper. Because the current scientific knowledge of Internet gaming addiction is copious in scope and appears relatively complex, this literature review attempts to reduce this confusion by providing an innovative framework by which all the studies to date can be categorized.

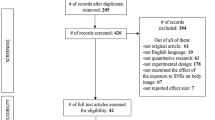

Methodology

A comprehensive literature search was conducted using the database Web of Knowledge. The following search terms (and their derivatives) were entered in relation to online video gaming: ‘excessive’, ‘problematic’, ‘compulsive’, and ‘addictive’. In addition, further studies were identified from supplementary sources, such as Google Scholar, and these were added in order to generate a more inclusive literature review. Studies were selected in accordance with the following inclusion criteria. Studies had to (i) contain empirical data (including everything from case studies through to surveys with thousands of participants), (ii) have been published after 2000 (as there were no studies on this topic prior to that date), and (iii) contain some kind of analysis relating to Internet gaming addiction. If studies referred to gaming addicts without specifying whether these were online and/or offline gamers, due to online games’ popularity it was assumed that at least some of the participants were online gamers and therefore these studies were included in the review. It should also be noted that studies investigating the playing of gambling games for free were excluded from the analysis as these have been examined in detail elsewhere in other reviews on internet gambling (e.g., Griffiths and Parke 2010; King et al. 2010).

Results

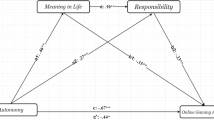

Three main categories of studies were identified, namely those concerned with (i) etiology, (ii) pathology and (iii) ramifications of Internet gaming addiction. Each of these also contained sub-topics that are conceptualized in the schematic framework in Fig. 1. The findings within each of these categories are described. This is followed by an evaluation of these studies in the final section of the paper.

Based upon the scientific empirical literature, it is argued that Internet gaming addiction appears to follow a continuum, with antecedents in etiology and risk factors, through to the development of a “full-blown” addiction, followed by ramifications in terms of negative consequences and potential treatment. These stages are interdependent as the risk factors influence the pathogenesis of addiction and the latter may similarly reinforce the former. Likewise, addiction leads to clinically significant negative consequences for the individual, which in turn may augment the pathological status of the former, requiring the individual to seek professional treatment.

This conceptual framework is further developed by drawing upon the relevant studies identified from the empirical literature. It should also be noted that only a small number of the studies exclusively fell within only one of the main categories and the associated sub-categories. Accordingly, many of the studies listed below are included in more than one of the sub-categories. Likewise, the sub-categories of psychophysiology and comorbidity were not placed in one of the main three categories, because they appeared to more closely resemble the intersection between the etiology and pathology of Internet gaming addiction.

Etiology/Risk

A number of studies have focused on illuminating the etiology of, and specifying risk factors for, Internet gaming addiction. These include internal factors, namely personality traits and motivations for playing, as well as an external factor, the structural game characteristics. Each of these is dealt with below.

Personality Traits

The first internal risk factor identified in the review was personality traits of gamers, which has been investigated in twelve studies (Allison et al. 2006; Caplan et al. 2009; Chiu et al. 2004; Chumbley and Griffiths 2006; Jeong and Kim 2010; Kim et al. 2008; Ko et al. 2005; Lemmens et al. 2010; Mehroof and Griffiths 2010; Parker et al. 2008; Peters and Malesky 2008; Porter et al. 2010). The methodologies employed ranged from a case study of an adolescent gamer (Allison et al. 2006) to a larger sample of this population (Parker et al. 2008), middle school and high school students (Chiu et al. 2004; Jeong and Kim 2010; Ko et al. 2005), undergraduate students (Chumbley and Griffiths 2006; Mehroof and Griffiths 2010), and large samples of MMORPG players (Caplan et al. 2009; Kim et al. 2008; Peters and Malesky 2008), as well as an unspecified sample of video gamers (Porter et al. 2010).

Personality traits were assessed using a variety of measures, including the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (Butcher et al. 1989), the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire (Eysenck and Eysenck 1996), the NEO Personality Inventory (Costa and McCrae 1985), a boredom inclination scale (Farrell 1990), the Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire (Buss and Perry 1992), the Narcissistic Personality Disorder Scale (Hwang 1995), the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (Rosenberg 1965), the Self-Control Scale (Tangney et al. 2004), emotional intelligence (Bar-On and Parker 2000), self-efficacy (based on Muris 2001; Sherer et al. 1982), and the Arnett Inventory of Sensation-Seeking (Arnett 1994).

In terms of the results, the following personality traits were found to be significantly related to Internet gaming addiction: avoidant and schizoid interpersonal tendencies (Allison et al. 2006), loneliness and introversion (Caplan et al. 2009), social inhibition (Porter et al. 2010), aggression and hostility (Caplan et al. 2009; Chiu et al. 2004; Kim et al. 2008; Mehroof and Griffiths 2010), boredom inclination (Chiu et al. 2004), sensation-seeking (Chiu et al. 2004; Mehroof and Griffiths 2010), diminished self-control and narcissistic personality traits (Kim et al. 2008), low self-esteem (Ko et al. 2005), neuroticism (Mehroof and Griffiths 2010; Peters and Malesky 2008), state and trait anxiety (Mehroof and Griffiths 2010), low emotional intelligence (Parker et al. 2008), low self-efficacy in real life as opposed to high self-efficacy in the virtual world (Jeong and Kim 2010), and diminished agreeableness (Peters and Malesky 2008). In summation, Internet gaming addiction appears to be accompanied with a variety of personality traits, which can be subsumed under the key characteristics of introversion, neuroticism and impulsivity. However, it must be noted that the personality traits that appear to have an association with Internet gaming addiction may not be unique to the disorder, and therefore until further research has been undertaken, it is hard to assess the etiological significance of such findings.

Motivations for Playing

A number of motivations for playing that put a player at risk for Internet gaming addiction were identified from the literature. In total, thirteen studies were identified (Beranuy et al. 2010; Caplan et al. 2009; Grüsser et al. 2005; Hsu et al. 2009; Hussain and Griffiths 2009b; King and Delfabbro 2009a, 2009b; King et al. 2011; Lu and Wang 2008; Ng and Wiemer-Hastings 2005; Wan and Chiou 2006a, 2006b, 2007). These included qualitative studies of MMORPG players (Beranuy et al. 2010), both adolescent and adult gamers (King and Delfabbro 2009b), and adolescent online game addicts (Wan and Chiou 2006b). Quantitative studies included large samples of MMORPG players (Caplan et al. 2009; Hussain and Griffiths 2009b; Ng and Wiemer-Hastings 2005), online game players (Lu and Wang 2008), video game players (King and Delfabbro 2009a; King et al. 2011), both adolescents and MMORPG players (Wan and Chiou 2006a), secondary school children (Grüsser et al. 2005), adolescents (Wan and Chiou 2007), and college students (Hsu et al. 2009). Apart from the specification of MMORPGs as game genre a number of participants were playing as mentioned above, in the other studies no explicit reference to game type was discernible.

Motivations for playing were assessed by the following means: semi-structured interviews (Beranuy et al. 2010; King and Delfabbro 2009b; Wan and Chiou 2006b) as well as theoretical frameworks (Choi et al. 2000; Myers, 1990; Williams et al. 2008). In addition to this, a number of assessment instruments were used, namely a questionnaire for assessing computer game play behavior in children (CSVK; Thalemann et al. 2004), an adapted version of the Exercise Addiction Inventory (Terry et al. 2004), the Video Game Playing Motivation Scale (PVGT; based on Young 1998), the Two-Factor Evaluation on Needs for Online Games (TENO; Wan and Chiou 2006a), and the Online Gaming Motivation Scale (Wan and Chiou 2007).

The results of the studies indicated that Internet gaming addiction is related to the following motivations for playing: coping with negative emotions, stress, fear and escape (Grüsser et al. 2005; Hussain and Griffiths 2009b; King and Delfabbro 2009a; Ng and Wiemer-Hastings 2005; Wan and Chiou 2006a, 2006b), dissociation (Beranuy et al. 2010), virtual friendship/relationships (Beranuy et al. 2010; Caplan et al. 2009; Hsu et al. 2009; King and Delfabbro 2009a; Ng and Wiemer-Hastings 2005), entertainment (Beranuy et al. 2010; Wan and Chiou 2006b), playfulness and loyalty (Lu and Wang 2008), empowerment, mastery, control, recognition, completion, excitement and challenge (King and Delfabbro 2009b; King et al. 2011; Wan and Chiou 2006b), curiosity and obligation (Hsu et al. 2009), reward (Hsu et al. 2009; King et al. 2010), immersion (Caplan et al. 2009), and generally high intrinsic motivation to play as opposed to extrinsic motivation (Wan and Chiou 2007). In summation, it appears that it is particularly motivations related to dysfunctional coping, socialization and personal satisfaction that serve as risk factors for developing Internet gaming addiction.

Structural Characteristics of the Game

Certain structural characteristics of the game itself are thought to make playing online games particularly appealing to persons who play excessively. A total of four studies were identified that have analyzed such characteristics (Chumbley and Griffiths 2006; King et al. 2010; Smahel et al. 2008; Thomas and Martin 2010). The samples included in the studies were MMORPG players (Smahel et al. 2008), video game players (King et al. 2010), and students within different stages in their education (Chumbley and Griffiths 2006; Thomas and Martin 2010). Again, for the last two participant groups, no specification with regards to game genre was referred to.

The methods employed to investigate structural characteristics of the game included: high and negative reinforcement of play via the game’s structural characteristics as based on the skill for playing required and investigated via self-report, as well as affective and playability measurements scored on Likert scales (Chumbley and Griffiths 2006), the Video Game Structural Characteristics Survey (King et al. 2010), questions about the relationship of the gamers to their virtual characters (Smahel et al. 2008), and game addiction with regards to different game genres (Thomas and Martin 2010).

The results indicated that structural characteristics of games appear to be related to addiction. More specifically, Internet games and arcade games were found to be more addictive than offline video games although these three different types of games were inadequately defined by the authors particularly in relation to internet games (Thomas and Martin 2010). Moreover, it has been found that structural characteristics affect players’ mood. That is, negative reinforcement led to frustration, whereas positive reinforcement resulted in game persistence, hypothetically allowing to link positive reinforcement to addiction (Chumbley and Griffiths 2006). In addition to this, particular game features were enjoyed significantly more by addicted players, namely adult content, finding rare in-game items, and watching videogame cut-scenes (King et al. 2010). Finally, addicted players appeared to be particularly proud of their avatars, i.e., they wanted to be like their virtual characters, and viewed the latter as superior compared to themselves (Smahel et al. 2008). In summation, certain structural characteristics of Internet games appear to put players at risk for developing an addiction to these games. Most notably, Internet games constructed in such a way so as to reinforce playing by various means appear to have a higher addictive potential than those that do not contain these structures, such as offline games.

Pathophysiology

Pathophysiology is one of the sub-categories that falls between etiology and pathology of Internet gaming addiction and thus it represents an aspect of the intersection between risk factors and the actual development of pathological behaviors and cognitions. Several studies have assessed the relationship between Internet gaming addiction and physiology. In total, seven such studies were identified (Cultrara and Har-El 2002; Dworak et al. 2007; Han et al. 2010; Hoeft et al. 2008; Ko et al. 2009; Thalemann et al. 2007). With regards to methods and participants, these studies included one case study of an adolescent role-playing gamer (Cultrara and Har-El 2002), as well as a small sample of young teenagers (Dworak et al. 2007), several studies comparing gaming addicts and healthy controls (Han et al. 2010; Han et al. 2007; Ko et al. 2009; Thalemann et al. 2007), as well as a student sample (Hoeft et al. 2008).

The associations between Internet gaming addiction and physical problems were assessed by the following means: functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI; Han et al. 2010; Hoeft et al. 2008; Ko et al. 2009), electroencephalography (EEG; Thalemann et al. 2007), genotyping (Han et al. 2007), polysomnographic measures and visual and verbal memory tests (Dworak et al. 2007), and medical examinations including the patient’s history, and physical, radiologic, intraoperative, and pathologic findings (Cultrara and Har-El 2002).

The results of the fMRI studies conducted revealed that during computer game cue presentation, gaming addicts showed similar neural processes and increased activity in brain areas associated with substance-related addictions and other behavioral addictions, such as pathological gambling. Significantly stronger activation in addicts relative to healthy controls was found in the left occipital lobe, parahippocampal gyrus, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, nucleus accumbens, right orbitofrontal cortex, bilateral anterior cingulate, medial frontal cortex, and the caudate nucleus (Han et al. 2010; Hoeft et al. 2008; Ko et al. 2009). Moreover, the gaming addicts’ emotional processing of game-relevant cues was found to be increased relative to that of casual gamers (Thalemann et al. 2007).

In a similar vein, those addicted to Internet gaming were found to have a higher prevalence of two polymorphisms of the dopaminergic system that are associated with substance-related addictions, namely the Taq1A1 allele of the dopamine D2 receptor and the Val158Met in the Catecholamine-O-Methyltransferase (COMT) genes (Han et al. 2007). Additionally, excessive online game play was associated with significantly reduced amounts of slow-wave sleep and declines in verbal memory performance and a prolonged sleep-onset latency (Dworak et al. 2007). Finally, it was reported that one patient excessively moved his jaw and tongue during online game play, to the end that he developed muscle hypertrophy and associated physical problems (Cultrara and Har-El 2002).

However, it must also be noted that although gaming addicts displayed stronger activation compared to non-addicts in these studies, the question remains as to whether this is specific to gaming addiction, or general to any activity that generates arousal (e.g., gambling), and whether these findings reflect causes or effects. Based on the studies presented here, it cannot be proved that the findings reported attest to the severity of the mental health problem if effects found are the result of exposure, anymore than differences in dopaminergic activity between drug and non-drug users attest to the severity of mental health problems for society at large. Despite such limitations, these studies appear to show that neither the causes nor the consequences of Internet gaming addiction are restricted to psychosocial factors. More specifically, the results of scientific studies demonstrate that Internet gaming addiction is associated with a wide variety of physiological, biochemical and neurological aberrations from the norm. This attests to the apparent severity of this mental health problem for society at large.

Comorbidity

Comorbidity was found to be one of the two categories that the current scientific literature focuses on that cannot adequately be subsumed under one of the main categories presented in the framework. The occurrence of further (sub)clinical symptoms can be a risk factor for Internet gaming addiction as well as an accompanying condition in such a way that they are interdependent. Therefore, in this review no claims regarding the direction of relationship are made.

A total of five studies assessing Internet gaming addiction and its comorbidity were identified (Allison et al. 2006; Batthyány et al. 2009; Chan and Rabinowitz 2006; Batthyány et al. 2009; Peng and Liu 2010). With regards to methodology, the participant groups investigated in the studies were relatively diverse. One study included the case of an adolescent gamer (Allison et al. 2006), and quantitative studies included high school students (Chan and Rabinowitz 2006), college students (Batthyány et al. 2009), online gamers (Peng and Liu 2010), as well as children diagnosed with ADHD (Han et al. 2009).

Internet gaming addiction was found to be associated with symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, depression, social phobia (Allison et al. 2006), school phobia (Batthyány et al. 2009), ADHD (Allison et al. 2006; Batthyány et al. 2009; Chan and Rabinowitz 2006; Han et al. 2009), as well as psychosomatic symptoms (Batthyány et al. 2009). These results reflect some of the findings of the section concerned with personality traits in that some of the latter may demarcate premorbid levels of diagnosed pathology.

Pathology/Addiction

Several studies have assessed pathological characteristics of addiction to Internet gaming. This section is subdivided into three sub-categories, namely the classification and assessment, epidemiology and phenomenology of Internet gaming addiction.

Classification/Assessment

A total of seven studies focusing on the classification and assessment of Internet gaming addiction were identified (Charlton and Danforth 2007; Griffiths 2010a, b; Kim and Kim 2010; King et al. 2010; Salguero and Moran 2002; Skoric et al. 2009; van Rooij et al. 2010). In terms of methodology, two case studies of male online gamers were included (Griffiths 2010a, b), large samples of adult MMORPG players (Charlton and Danforth 2007), elementary school video gamers (Skoric et al. 2009), student and non-student video game players (King et al. 2009), teenagers (Salguero and Moran 2002), elementary and high school students (Kim and Kim 2010), and secondary school adolescents (van Rooij et al. 2010).

In each of the studies, different terminologies were applied for similar phenomena, ranging from compulsive Internet use (van Rooij et al. 2010), problem video game playing (King et al. 2009; Salguero and Moran 2002) and problematic online game use (Kim and Kim 2010) to video game addiction (Skoric et al. 2009) and online gaming addiction (Charlton and Danforth 2007; Griffiths 2010a, b). Similarly, a variety of measurement instruments was used in order to assess the specified problematic/addictive behaviors, namely the Compulsive Internet Use Scale (Meerkerk et al. 2009), the Problematic Video Game Playing Test (adapted from Young 1998), the Problem Video Game Playing Scale (Salguero and Moran 2002), the Problematic Online Game Use Scale (Kim and Kim 2010), an assessment of addiction tendencies (based on American Psychiatric Association 2000), the Addiction-Engagement Questionnaire (modified from Charlton 2002), and the Game Addiction Scale (based on Lemmens et al. 2009).

The results of the studies indicate that Internet gaming addiction appears to be a viable construct worthy of individual and independent investigation (van Rooij et al. 2010). It must be noted that the researchers working on this study used the terms addiction and compulsive use interchangeably, so that it seems appropriate to refer to addictions in this case. Furthermore, it was emphasized that addiction cannot be equated with problematic use. Some of the studies suggest that problematic game playing lies on a continuum towards addiction, as it can result in addiction symptoms, namely salience, mood modification, tolerance, withdrawal, conflict, and relapse (Griffiths 2010b; King et al. 2009; Salguero and Moran 2002). Others adopt more detailed approaches to classification, claiming that problematic use is characterized by investing much time and energy in the game, euphoria, tolerance, denial, and a preference for online relationships (Kim and Kim 2010). This finding is in line with the result that addiction core criteria (conflict, withdrawal symptoms, relapse, reinstatement, and behavioral salience) must be distinguished from peripheral criteria (cognitive salience, tolerance, and euphoria), for only the former were found to load on an addiction factor (Charlton and Danforth 2007). In a similar vein, it was found that addiction does not equal excessive engagement: Only when significant negative consequences of excessive gaming occur can one speak of an addiction (Griffiths 2010a, 2010b; Skoric et al. 2009). A more detailed evaluation of this finding will take place in the discussion.

Epidemiology

From the literature, ten studies were identified assessing the prevalence of Internet gaming addiction (Batthyány et al. 2009; Grüsser et al. 2005; Grüsser, Thalemann, and Griffiths 2007a; Jeong and Kim 2010; Ng and Wiemer-Hastings 2005; Porter et al. 2010; Rehbein et al. 2010; Thomas and Martin 2010; Yee 2006a, 2006b). The following samples were included: 1,231 students in grades 3 to 5 (Batthyány et al. 2009), 323 children with a mean age of 12 years (Grüsser et al. 2005), 44,910 9th graders (Rehbein et al. 2010), 600 middle and high school students (Jeong and Kim 2010), 2,031 secondary, college and university students (Thomas and Martin 2010), 7,069 gamers with a mean age of 21 years (Grüsser et al. 2007a), 91 MMORPG and offline game players (Ng and Wiemer-Hastings 2005), 1,945 video gamers predominantly below 30 years (Porter et al. 2010), and 30,000 MMORPG players (Yee 2006a, 2006b). The prevalence of Internet gaming addiction was assessed with the measures referred to in the sections on motivations for playing and classification/assessment.

The results of the studies indicate that approximately 12% of students in third to fifth grades played computer games excessively (i.e., were classified as abusers and/or addicts), 10% abused these games (i.e., they scored between 7 and 13 on the Fragebogen zum Computerspielverhalten bei Kindern und Jugendlichen [CSVK-R]), and 3% could be categorized as being dependent upon engaging with them (i.e., they scored 13 and above on the CSVK-R) (Batthyány et al. 2009). Furthermore, 9% of 12-year old children fulfilled the criteria for excessive computer and video game playing (Grüsser et al. 2005). Three percent of male and 0.3% of female ninth graders could be diagnosed as being dependent on video games, while 5% of boys and 0.5% of girls were at risk for developing dependence (Rehbein et al. 2010). Four percent of students met the criteria for addiction to video arcade games, and 5% for computer games and the Internet respectively (Thomas and Martin 2010). Finally, 2.2% of middle and high school students were found to be addicted to Internet games (Jeong and Kim 2010).

The studies including gamers specifically reveal higher prevalence rates. Problematic gaming behaviors were present in 8% of video gamers (Porter et al. 2010). Other researchers claimed that 12% of online gamers met at least three criteria for addiction (Grüsser et al. 2007a). In addition to this, the findings suggest that 12% of MMORPG players preferred to talk to people in game rather than in real life and were happier in game than anywhere else (Ng and Wiemer-Hastings 2005). Furthermore, 8% of MMORPG players spent a minimum of 40 h in game per week, 61% spent a minimum of ten hours in game continuously, 30% stayed in game although they did not enjoy it, 18% experienced academic, health, financial or relationship problems, and 50% considered themselves to be addicted (Yee 2006a, 2006b). Nevertheless, although a number of studies have assessed the prevalence of Internet gaming addiction, they used dissimilar assessment instruments as well as cut-offs and included diverse participant groups. This may explain the large variability in prevalence percentages. Therefore, the quoted results do not allow for making definite overall claims with regards to epidemiology at this point in time.

Phenomenology

Ten studies have investigated the experience of Internet gaming addiction from a phenomenological perspective (Allison et al. 2006; Chappell et al. 2006; Charlton and Danforth 2007; Chou and Ting 2003; Hussain and Griffiths 2009a; Rau et al. 2006; Seah and Cairns 2007; Wan and Chiou 2006a, 2006b; Wood and Griffiths 2007). The methodologies used were qualitative, including a case study of an adolescent excessive MMORPG player (Allison et al. 2006), ten adolescent online game addicts (Wan and Chiou 2006b), and 12 Everquest players (Chappell et al. 2006), and quantitative, including 442 adult MMORPG players (Charlton and Danforth 2007), adults (Chou and Ting 2003; Hussain and Griffiths 2009a), adult and teenage online gamers (Rau et al. 2006), students (Seah and Cairns 2007; Wood and Griffiths 2007), and 16–24-year old adolescents and MMORPG players (Wan and Chiou 2006a).

The experiences of different aspects of Internet gaming addiction were assessed using different methodologies, such as psychiatric interviews (Allison et al. 2006), in-depth interviews assessed with interpretative phenomenological frameworks (Chappell et al. 2006), and content analysis (Wan and Chiou 2006b). In addition to this, several studies have assessed flow experience (Chou and Ting 2003; Wan and Chiou 2006a), immersion (Seah and Cairns 2007) and associated time loss (Rau et al. 2006; Wood and Griffiths 2007) during game-play quantitatively, as based on Csikszentmihalyi’s (1990) conceptualization of flow (i.e., the optimum experience a person achieves when performing an activity). Finally, the Addiction-Engagement Questionnaire (modified from Charlton 2002) has also been used.

The results suggest that Internet gaming addiction is associated with large amounts of time, i.e., up to 16 h per day, spent in game, lack of sleep and a shortage of social and romantic contacts (Allison et al. 2006). Moreover, it is experienced similarly to any other substance-related addiction (Hussain and Griffiths 2009a), in such a way that salience, mood modification, conflict, withdrawal symptoms, cravings and relapse occurred (Chappell et al. 2006; Charlton and Danforth 2007). Additionally, online game addicts perceived gaming as providing compensation for needs which were not met in their real lives, and that it has become the focus of their lives (Wan and Chiou 2006b).

In terms of flow and associated experiences, the studies found that the experience of flow and in-game immersion was associated with addiction (Chou and Ting 2003; Seah and Cairns 2007). Another study found that it was game novices who experienced more flow when playing for about one hour, whereas for expert players it took longer to experience flow (Rau et al. 2006). In line with this and contrary to the results of the above mentioned studies, it was also found that flow negatively correlated with addictive inclination (Wan and Chiou 2006a). Furthermore, it has also been found that the experience of time loss does not necessarily precipitate addiction (Wood and Griffiths 2007). These findings will be evaluated in the discussion.

Ramifications

Several studies have assessed the ramifications of Internet gaming addiction. These can be summarized primarily as negative consequences that may require professional treatment. These topics are dealt with below.

Negative Consequences

Nineteen studies have highlighted the negative consequences of Internet gaming addiction beyond the comorbidities outlined earlier (Allison et al. 2006; Batthyány et al. 2009; Chan and Rabinowitz 2006; Chiu et al. 2004; Chuang 2006; Dworak et al. 2007; Griffiths et al. 2004; Grüsser, Thalemann and Griffiths 2007a; Hussain and Griffiths 2009a, 2009b; Jeong and Kim 2010; King and Delfabbro 2009b; Lemmens et al. 2010; Liu and Peng 2009; Peters and Malesky 2008; Rehbein et al. 2010; Skoric et al. 2009; Yee 2006a, 2006b). These have been investigated in children (Batthyány et al. 2009; Skoric et al. 2009), teenagers (Allison et al. 2006; Chan and Rabinowitz 2006; Chiu et al. 2004; Dworak et al. 2007; Jeong and Kim 2010; Lemmens et al. 2010; Rehbein et al. 2010), teenagers and adults (King and Delfabbro 2009b), MMORPG players (Griffiths et al. 2004; Grüsser, Thalemann and Griffiths 2007a; Hussain and Griffiths 2009a, 2009b; Liu and Peng 2009; Peng and Liu 2010; Peters and Malesky 2008; Yee 2006a, 2006b), and epilepsy patients (Chuang 2006).

The negative consequences were assessed via a variety of psychological tests and psychiatric interviews, academic achievement, EEG, MRI, polysomnographic measurements, visual and verbal memory tests, asking what was sacrificed for gaming, the psychosocial context of gaming behavior, social competence, preference for a virtual life, relationship formation, the Internet Addiction Scale modified for video games (Widyanto and McMurran 2004), Conners’ Parent Rating Scale (Conners et al. 1998), Questionnaire on Computer Game Behavior of Children (Thalemann et al. 2004), the Questionnaire for Differentiated Assessment of Addiction (Grüsser et al. 2007b), the Exercise Addiction Inventory (adapted from Terry et al. 2004), the Game Addiction Scale (Lemmens et al. 2009), the UCLA Loneliness Scale (Russell 1996), the Satisfaction with Life Scale (Diener et al. 1985), the Self-Esteem Scale (Rosenberg et al. 1989), the Negative Life Consequences Scale (Liu et al. 2008), the Generalized Problematic Internet Use Scale (Caplan 2002), the social control subscale of the Social Skill Inventory (Riggio 1989), the CES Depression Scale (Mirowsky and Ross 1992), and the Videogame Dependency Scale (adapted from Rehbein and Borchers 2009).

The results of these studies show that Internet gaming addiction can lead to a wide variety of negative consequences. These include psychosocial problems, namely an obsession with gaming, no real life relationships (Allison et al. 2006), inattention (Batthyány et al. 2009; Chan and Rabinowitz 2006), aggressive/oppositional behavior and hostility (Chan and Rabinowitz 2006; Chiu et al. 2004), stress (Batthyány et al. 2009), maladaptive coping (Batthyány et al. 2009; Hussain and Griffiths 2009a, 2009b), decreased academic achievement (Chiu et al. 2004; Jeong and Kim 2010; Rehbein et al. 2010; Skoric et al. 2009), declines in verbal memory performance (Dworak et al. 2007), sacrificing hobbies, sleep, work, education, socializing, time with partner/family as well as associated problems (Batthyány et al. 2009; Griffiths et al. 2004; King and Delfabbro 2009b; Liu and Peng 2009; Peng and Liu 2010; Peters and Malesky 2008; Rehbein et al. 2010; Yee 2006a, 2006b), dissociation (Hussain and Griffiths 2009a), lower psychosocial well-being and loneliness (Lemmens et al. 2010), maladaptive cognitions (Peng and Liu 2010), and increased thoughts of committing suicide (Rehbein et al. 2010). Moreover, psychosomatic problems were found to be consequences of Internet gaming addiction. These included psychosomatic challenges (Batthyány et al. 2009), seizures (Chuang 2006), and sleep abnormalities (Allison et al. 2006; Dworak et al. 2007). Altogether, the relatively long list of potential negative consequences clearly indicates that Internet gaming addiction is a phenomenon that cannot be taken lightly and deserves more extensive recognition.

Treatment

Three studies have particularly assessed the treatment of Internet gaming addiction (Beranuy et al. 2010; Han et al. 2010; Han et al. 2009). These studies included a qualitative analysis of nine male MMORPG addicts aged 16–26 years (Beranuy et al. 2010), a comparative study of video game addicts and healthy controls between 17 and 29 years of age (Han et al. 2010), and a sample of 62 children with Internet video game addiction and comorbid ADHD (Han et al. 2009).

With regards to methodology, one investigation (Beranuy et al. 2010) was a descriptive analytic-relational study using semi-structured interview protocols including questions on sociodemographics, family, reasons for therapy, relationships, game usage, and symptom exploration. Its aim was to explore addictive playing of MMORPGs in players undergoing treatment for their gaming addiction. Another study (Han et al. 2010) was experimental, using fMRI for assessing brain activation during game cue exposure in addicts compared to healthy controls, as well as psychometric measurements, including the Internet Addiction Test (Young 1998), Beck’s Depression Inventory (Beck and Steer 1993), and the structured clinical diagnostic interview (First et al. 1996, 1997). Its aim was to investigate the effects of bupropin sustained release treatment on Internet video game addicts. The final study (Han et al. 2009) used a computerized neurocognitive function test (Kim et al. 2006), the Internet Addiction Test (Young 1998), and the ADHD Rating Scale (So et al. 2002) to assess the effects of methylphenidate on Internet video game play in children with ADHD.

The results demonstrated that Internet gaming addiction develops as playing times increase significantly, as loss of control, a narrow behavioral focus and serious life conflicts appear. Moreover, the addiction symptoms were similar to those experienced by persons addicted to substances, including salience, mood modification, loss of control, craving, and serious adverse effects, and a variety of further psychosocial problems (Beranuy et al. 2010). Furthermore, following a six-week period of psychopharmacological treatment, craving for Internet video game play as well as brain activities associated with addictions in Internet video game addicts were significantly decreased, while daily life functioning was increased (Han et al. 2010). Finally, an eight-week psychopharmacological treatment targeting ADHD symptoms resulted in a decrease in Internet gaming addiction and playing times (Han et al. 2009). The efficacy of psychopharmacological treatment for treating Internet gaming addiction once again highlights the biochemical underpinnings of this disorder. This demonstrates not only that Internet gaming addiction is a potential mental health concern worthy of treatment, but also that this treatment may alleviate a wide variety of psychosocial problems as a result of the addiction to playing these games.

Discussion

This systematic review has demonstrated that research into Internet gaming addiction has proliferated over the last few years. From the published studies, it appears that the current scientific knowledge of Internet gaming addiction can be categorized into etiology, pathology, and associated ramifications. In terms of etiology, it would appear that personality traits, motivations for playing, and the structural characteristics of the games are of particular importance. Furthermore, pathophysiology and comorbidity appear to be intersections between risk factors and the actual development of pathological behaviors and cognitions. The analysis of pathology itself can be furthermore subclassified into its assessment and addiction classification, as well as epidemiology and phenomenology. Finally, the ramifications of Internet gaming addiction were found to be negative consequences, which allow for the behavior to be classified as pathological as based on established clinical standards (American Psychiatric Association 2000). In line with this, Internet gaming addiction may require professional treatment.

On a neuronal and biochemical level, Internet gaming addiction appears to be similar to other substance-related addictions, thus supporting the assumption that it is an addiction, albeit a behavioral one, like gambling addiction (Batthyány and Pritz 2009; Grüsser and Thalemann 2006). Firstly, the studies presented suggest that Internet gaming addicts’ brains react to game-relevant cues the way that substance addicts’ brains react to rewards associated with substance-related addictions (Kalivas and Volkow 2005; Knutson and Cooper 2005). Secondly, the efficacy of psychopharmacological interventions that may alleviate Internet gaming addiction symptoms, support its biochemical, cognitive, and behavioral basis. Thirdly, the genetic polymorphisms found in Internet gaming addicts are similar to those associated with reward dependence in alcohol (Blum et al. 1990), cocaine addictions (Noble et al. 1993), and pathological gambling (Comings et al. 1996). To summarize, Internet gaming addiction is a behavioral addiction that appears to be similar to substance-related addictions and thus it supports the idea of a syndrome model of addiction. Put simply, Shaffer et al. (2004) suggest that each addiction – whether it be to gambling, drugs, sex, or the Internet – might be a distinctive expression of the same underlying syndrome (i.e., addiction is a syndrome with multiple opportunistic expressions). These findings emphasize the pathological status of Internet gaming addiction and demarcate the latter as a mental health concern that is increasingly gaining recognition.

Another aspect that deserves closer scrutiny is the dissimilarity of findings with regards to whether (and in how far) flow experience is associated with addiction to Internet games. Studies are ambiguous in suggesting that flow correlates with addiction, as some seem to suggest a relationship (Chou and Ting 2003; Seah and Cairns 2007), whereas other findings imply the opposite (Wan and Chiou 2006b; Wood and Griffiths 2007). From a theoretical perspective, flow is characterized as an optimal experience (Csikszentmihalyi 1990). No one would disagree with the fact that addiction is anything but optimal. Therefore, being addicted to the flow state experienced during Internet gaming may carry with it the problems that addiction implies. The dissimilarity between the findings may be explained by different conceptualizations of addiction employed in such a way that excessive engagement is equated with pathology. However, it has been shown that a distinction between excess and addiction makes sense from a scientific point of view (Charlton and Danforth 2007; Griffiths 2010a, b).

Against this background, it seems likely that excessive players experience flow because their game playing is principally characterized by excitement and challenge (Wan and Chiou 2006b), which lies at the heart of flow experience. Flow occurs when a person is absorbed by a task in which the task’s level of challenge and the individual’s skill are matched (Csikszentmihalyi 1990). Contrary to this, it seems unlikely that addicted players experience flow, for they tend to continue playing although they do not enjoy it (Yee 2006a, 2006b), which attests to the compulsiveness of their behaviors. Therefore, it appears probable that addicts have already left the flow experience behind. This provides additional support to the idea that some players who engage in Internet gaming excessively can develop a full-blown addiction to it.

In relation to this, another important finding from the studies is the distinction that has been made between excessive engagement and addiction (Charlton and Danforth 2007; Griffiths 2010a, b; Skoric et al. 2009). Excessive (problematic) engagement was found in approximately 8–12% of young persons, whereas addiction seems to be present in 2–5% of children, teenagers and students. Furthermore, one study found that 12% of online game players met at least three addiction criteria (Grüsser et al. 2007a, b). This is in line with adopting either monothetic or polythetic formats for addiction diagnosis, as set forth by Lemmens et al. (2009). In the former, all addiction criteria must be met in order to diagnose someone with gaming addiction, whereas in the latter, only half of them need to be endorsed. What follows as a consequence of the utilization of these dissimilar frameworks is the apparent discrepancy between prevalence estimates.

From the studies reviewed, it furthermore appears that MMORPG players particularly experienced symptoms associated with addiction, such as tolerance, mood modification, and negative psychosocial consequences, and half of them acknowledged that they were addicted to playing these games. In comparison to the general population of youth and young adults, it may be deduced that the prevalence of Internet gaming addiction is relatively high in the collective population of the MMORPG players that were included in the studies referenced. It has also been claimed that “MMOGs are particularly good at simultaneously tapping into what is typically formulated as game/not game, social/instrumental, real/virtual. And this mix is exactly what is evocative and hooks many people” (Taylor 2006, pp. 153–154). This emphasizes the importance of the particular game genre’s structural characteristics in the etiology of Internet gaming addiction, which may necessitate further scientific exploration.

Although this systematic literature review is specific in that it does not present Internet gaming addiction as a type of Internet addiction, it must be conceded that in the studies that were included, dissimilar foci were adopted with regards to the respective game genres analyzed. As mentioned in the introduction, a variety of games are accessible and playable via the Internet, each of which may entail dissimilar addictive potentials. For a number of studies, particularly those dealing with video games, it is unclear to what extent these games were specifically played on the Internet or offline. Furthermore, there are multiple forms of Internet gaming ranging from multi-player to single games, and complex to simple skills-based. In this review, no attempt was made to compare findings across similar types of gaming (often because the authors of the studies themselves had not made these distinctions), raising the question of the validity of combining studies reporting MMORPG, video games and other non-specified game genres. In light of this, researchers are advised to carefully describe the games their participants are playing in order to circumvent this difficulty and to increase the external validity of their findings to specific populations.

It should also be noted that there are different cultural and social factors associated with the environment that participants were recruited from in various studies that are outlined in this review. This could be highly relevant given that many studies on Internet gaming have been conducted in South East Asian countries where the social infrastructure fosters the promotion of professional competitions located in large venues that include social interactions among players, or where strong ego and image identities are derived from public recognition of gaming skills.

With regards to psychopathological status, it seems fruitful to distinguish between excessive engagement and addiction as suggested by past research (Charlton and Danforth 2007). This is a requirement particularly when taking into consideration the context of the American Psychiatric Association’s definition of what constitutes a mental disorder worthy of professional treatment. According to the APA, a mental disorder is a “clinically significant behavioral or psychological syndrome or pattern that occurs in an individual and that is associated with present distress (…) or disability (i.e., impairment in one or more important areas of functioning) or with a significantly increased risk of suffering death, pain, disability, or an important loss of freedom” (American Psychiatric Association 2000, p. xxxi). Accordingly, only when the condition is experienced as significantly impairing can one speak of an addiction, which is clearly not the case for excessive gamers who enjoy themselves while playing their games and for whom their gaming does not result in significant negative consequences. In line with this, researchers must be cautious in deploying the label “addiction” for it does not merely denote the extreme utilization of substances or engagement in certain behaviors, but it demarcates a genuine mental health problem.

For that reason, future researchers are advised to properly investigate what they claim to be an addiction in order to make sure that their identification of pathology is commensurate with clinical parlance even within the confinements of research using surveys for diagnosis only. Related to this is the utilization of a wide variety of assessment instruments to diagnose addiction, most of which have not been validated. Likewise, many studies used non-representative self-selected samples and small sample sizes. This obstructs the comparability of results, but it also puts into question the validity of diagnosis. Clearly, future researchers are advised not to develop additional measurement instruments, but to assess the validity and reliability of those already constructed against the official criteria of substance dependence as established by the American Psychiatric Association (2000).

Notes

A guild is a social grouping of people in-game, usually established around common goals, such as accessing the respective game’s high-end content collectively (Ducheneaut et al. 2007).

References

Allison, S. E., von Wahlde, L., Shockley, T., & Gabbard, G. O. (2006). The development of the self in the era of the Internet and role-playing fantasy games. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 163(3), 381–385.

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders—Text revision. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association.

Arnett, J. (1994). Sensation seeking: a new conceptualization and a new scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 16, 289–296.

Bar-On, R., & Parker, J. D. A. (2000). The Bar-On EQ-i:YV: Technical manual. Toronto: Multi-Health Systems.

Batthyány, D., & Pritz, A. (Eds.). (2009). Rausch ohne Drogen. Wien: Springer.

Batthyány, D., Müller, K. W., Benker, F., & Wölfling, K. (2009). Computer game playing: clinical characteristics of dependence and abuse among adolescents. Wiener Klinsche Wochenschrift, 121(15–16), 502–509.

Beck, A. T., & Steer, R. (1993). Manual for the Beck depression inventory. San Antonio: The Psychological Corporation.

Beranuy, M., Carbonell, X., & Griffiths, M. (2010). A qualitative analysis of online gaming addicts in treatment. Submitted manuscript.

Blum, K., Noble, E. P., Sheridan, P. J., et al. (1990). Allelic association of human dopamine D2 receptor gene in alcoholism. Journal of the American Medical Association, 263, 2055–2060.

Buss, A. H., & Perry, M. (1992). The aggression questionnaire. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63, 452–459.

Butcher, J. N., Dahlstrom, W. G., Graham, J. R., Tellegen, A., & Kaemmer, B. (1989). The Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2 (MMPI-2): Manual for administration and scoring. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Caplan, S. E. (2002). Problematic internet use and psychosocial well-being: development of a theory-based cognitive-behavioral measurement instrument. Computers in Human Behavior, 18(5), 553–575.

Caplan, S. E., Williams, D., & Yee, N. (2009). Problematic internet use and psychosocial well-being among MMO players. Computers in Human Behavior, 25(6), 1312–1319.

Chan, P. A., & Rabinowitz, T. (2006). A cross-sectional analysis of video games and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms in adolescents. Annals of General Psychiatry, 5(1), 16–26.

Chappell, D., Eatough, V., Davies, M. N. O., & Griffiths, M. D. (2006). Everquest—It’s just a computer game right? An interpretative phenomenological analysis of online gaming addiction. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 4, 205–216.

Charlton, J. P. (2002). A factor-analytic investigation of computer ‘addiction’ and engagement. British Journal of Psychology, 93, 329–344.

Charlton, J. P., & Danforth, I. D. W. (2007). Distinguishing addiction and high engagement in the context of online game playing. Computers in Human Behavior, 23(3), 1531–1548.

Chiu, S. I., Lee, J. Z., & Huang, D. H. (2004). Video game addiction in children and teenagers in Taiwan. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 7(5), 571–581.

Choi, D., Kim, H., & Kim, J. (2000). A cognitive and emotional strategy for computer game design. Journal of MIS Research, 10, 165–187.

Chou, T. J., & Ting, C. C. (2003). The role of flow experience in cyber-game addiction. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 6(6), 663–675.

Chuang, Y. C. (2006). Massively multiplayer online role-playing game-induced seizures: a neglected health problem in Internet addiction. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 9(4), 451–456.

Chumbley, J., & Griffiths, M. (2006). Affect and the computer game player: the effect of gender, personality, and game reinforcement structure on affective responses to computer game-play. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 9(3), 308–316.

Comings, D. E., Rosenthal, R. J., Lesieur, H. R., et al. (1996). A study of the dopamine D2 receptor gene in pathological gambling. Pharmacogenetics, 6, 223–234.

Conners, C. K., Sitarenios, G., Parker, J. D., & Epstein, J. N. (1998). The revised Conners’ Parent Rating Scale (CPR-R): Factor structure, reliability, and criterion validity. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 26(4), 257–268.

Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1985). The NEO personality inventory manual. Odessa: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: the psychology of optimal experience. New York: HarperCollins.

Cultrara, A., & Har-El, G. (2002). Hyperactivity-induced suprahyoid muscular hypertrophy secondary to excessive video game play: a case report. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, 60(3), 326–327.

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71–75.

Ducheneaut, N., Yee, N., Nickell, E., & Moore, R. J. (2007). The life and death of online gaming communitites: A look at guilds in World of Warcraft. San Jose: Paper presented at the CHI.

Dworak, M., Schierl, T., Bruns, T., & Struder, H. K. (2007). Impact of singular excessive computer game and television exposure on sleep patterns and memory performance of school-aged children. Pediatrics, 120(5), 978–985.

Eysenck, H. J., & Eysenck, S. G. B. (1996). Manual of the Eysenck Personality Scales (EPS adult) (revisedth ed.). London: Hodder & Stoughton Educational.

Farrell, E. (1990). Hanging in and dropping out: Voices of at-risk high school students. New York: Teachers College Press.

First, M. B., Gibbon, M., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. W. (1996). Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders: Clinician Version (SCID-CV): Administration booklet. Washington, D. C.: American Psychiatric Press.

First, M. B., Gibbon, M., Spitzer, R. L., Williams, J. B. W., & Benjamin, L. S. (1997). Structural Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (R) Axis II Personality Disorders (SCID-II). Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Press.

Griffiths, M. D. (2010a). Online gaming addiction: Fact or fiction? In W. Kaminski & M. Lorber (Eds.), Clash of realities (pp. 191–203). Munch: Kopaed.

Griffiths, M. D. (2010b). The role of context in online gaming excess and addiction: some case study evidence. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 8(1), 119–125.

Griffiths, M. D., & Parke, J. (2010). Adolescent gambling on the internet: a review. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, 22, 59–75.

Griffiths, M. D., Davies, M. N. O., & Chappell, D. (2004). Demographic factors and playing variables in online computer gaming. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 7(4), 479–487.

Grüsser, S. M., & Thalemann, C. N. (Eds.). (2006). Verhaltenssucht—Diagnostik, Therapie, Forschung. Bern: Hans Huber.

Grüsser, S. M., Thalemann, R., Albrecht, U., & Thalemann, C. N. (2005). Exzessive Computernutzung im Kindesalter—Ergebnisse einer psychometrischen Erhebung. Wiener Klinische Wochenschrift, 117(5–6), 188–195.

Grüsser, S. M., Thalemann, R., & Griffiths, M. D. (2007a). Excessive computer game playing: evidence for addiction and aggression? Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 10(2), 290–292.

Grüsser, S. M., Wölfling, K., Düffert, S., et al. (2007b). Questionnaire on differentiated assessment of addiction (QDAA). Göttingen: Hogrefe.

Han, D. H., Lee, Y. S., Yang, K. C., Kim, E. Y., Lyoo, I. K., & Renshaw, P. F. (2007). Dopamine genes and reward dependence in adolescents with excessive internet video game play. Journal of Addiction Medicine, 1(3), 133–138.

Han, D. H., Lee, Y. S., Na, C., Ahn, J. Y., Chung, U. S., Daniels, M. A., et al. (2009). The effect of methylphenidate on Internet video game play in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 50(3), 251–256.

Han, D. H., Hwang, J. W., & Renshaw, P. F. (2010). Bupropion sustained release treatment decreases craving for video games and cue-induced brain activity in patients with Internet video game addiction. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 18(4), 297–304.

Hoeft, F., Watson, C. L., Kesler, S. R., Bettinger, K. E., & Reiss, A. L. (2008). Gender differences in the mesocorticolimbic system during computer game-play. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 42(4), 253–258.

Hsu, S. H., Wen, M. H., & Wu, M. C. (2009). Exploring user experiences as predictors of MMORPG addiction. Computers & Education, 53(2), 990–999.

Huizinga, J. (1938). Homo ludens: A study of the play-element in culture. Boston: Beacon.

Hussain, Z., & Griffiths, M. D. (2009a). The attitudes, feelings, and experiences of online gamers: a qualitative analysis. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 12(6), 747–753.

Hussain, Z., & Griffiths, M. D. (2009b). Excessive use of massively-multi-player online role-playing games: a pilot study. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction., 7, 563–571.

Hwang, S. T. (1995). Development of diagnostic criteria for personality disorder. Seoul: Yonsei University. Master‘s thesis.

Jeong, E. J., & Kim, D. W. (2010). Social activities, self-efficacy, game attitudes, and game addiction. Cyberpsychology, Behavior & Social Networking, e-pub ahead of print.

Kalivas, P. W., & Volkow, N. D. (2005). The neural basis of addiction: a pathology of motivation and choice. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 162, 1403–1413.

Kim, M. G., & Kim, J. (2010). Cross-validation of reliability, convergent and discriminant validity for the problematic online game use scale. Computers in Human Behavior, 26(3), 389–398.

Kim, S. W., Shin, I. S., Kim, J. M., Yang, S. J., Shin, H. Y., & Yoon, J. S. (2006). Association between attitude toward medication and neurocognitive function in schizophrenia. Clinical Neuropharmacology, 29, 197–205.

Kim, E. J., Namkoong, K., Ku, T., & Kim, S. J. (2008). The relationship between online game addiction and aggression, self-control and narcissistic personality traits. European Psychiatry, 23(3), 212–218.

King, D. L., & Delfabbro, P. (2009a). Motivational differences in problem video game play. Journal of CyberTherapy & Rehabilitation, 2(2), 139–149.

King, D. L., & Delfabbro, P. (2009b). Understanding and assisting excessive players of video games: a community psychology perspective. The Australian Community Psychologist, 21(1), 62–74.

King, D. L., Delfabbro, P. H., & Zajac, I. T. (2009). Preliminary validation of a new clinical tool for identifying problem video game playing. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, e-pub ahead of print.

King, D. L., Delfabbro, P. H., & Griffiths, M. D. (2010). The convergence of gambling and digital media: implications for gambling in young people. Journal of Gambling Studies, 26, 175–187.

King, D. L., Delfabbro, P. H., & Griffiths, M. D. (2011). The role of structural characteristics in problematic video game play: an empirical study. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. doi:10.1007/s11469-010-9289-y.

Knutson, B., & Cooper, J. C. (2005). Functional magnetic resonance imaging of reward prediction. Current Opinion in Neurology, 18, 411–417.

Ko, C. H., Yen, J. Y., Chen, C. C., Chen, S. H., & Yen, C. F. (2005). Gender differences and related factors affecting online gaming addiction among Taiwanese adolescents. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 193(4), 273–277.

Ko, C. H., Liu, G. C., Hsiao, S. M., Yen, J. Y., Yang, M. J., Lin, W. C., et al. (2009). Brain activities associated with gaming urge of online gaming addiction. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 43(7), 739–747.

Lemmens, J. S., Valkenburg, P. M., & Peter, J. (2009). Development and validation of a game addiction scale for adolescents. Media Psychology, 12(1), 77–95.

Lemmens, J. S., Valkenburg, P. M., & Peter, J. (2010). Psychosocial causes and consequences of pathological gaming. Computers in Human Behavior, e-pub ahead of print.

Liu, M., & Peng, W. (2009). Cognitive and psychological predictors of the negative outcomes associated with playing MMOGs (massively multiplayer online games). Computers in Human Behavior, 25, 1306–1311.

Liu, M., Ko, H., & Wu, J. (2008). The role of positive/negative outcome expectancy and refusal self-efficacy of Internet use on Internet addiction among college students in Taiwan. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 11, 451–457.

Lu, H. P., & Wang, S. M. (2008). The role of Internet addiction in online game loyalty: an exploratory study. Internet Research, 18(5), 499–519.

Meerkerk, G. J., Van Den Eijnden, R., Vermulst, A. A., & Garretsen, H. F. L. (2009). The Compulsive Internet Use Scale (CIUS): some psychometric properties. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 12(1), 1–6.

Mehroof, M., & Griffiths, M. D. (2010). Online gaming addiction: the role of sensation seeking, self-control, neuroticism, aggression, state anxiety, and trait anxiety. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 13(3), 313–316.

Mirowsky, J., & Ross, C. E. (1992). Age and depression. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 33, 187–205.

Muris, P. (2001). A brief questionnaire for measuring self-efficacy in youths. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 23(3), 145–149.

Myers, D. (1990). A Q-study of game player aesthetics. Simulation & Gaming, 21, 375–396.

Ng, B. D., & Wiemer-Hastings, P. (2005). Addiction to the internet and online gaming. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 8(2), 110–113.

Noble, E. P., Blum, K., Khalsa, M. E., et al. (1993). Allelic association of the D2 dopamine receptor gene with cocaine dependence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 33, 271–285.

Parker, J. D. A., Taylor, R. N., Eastabrook, J. M., Schell, S. L., & Wood, L. M. (2008). Problem gambling in adolescence: relationships with internet misuse, gaming abuse and emotional intelligence. Personality and Individual Differences, 45(2), 174–180.

Peng, W., & Liu, M. (2010). Online gaming dependency: a preliminary study in China. CyberPsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 13(3), 329–333.

Peters, C. S., & Malesky, L. A. (2008). Problematic usage among highly-engaged players of massively multiplayer online role playing games. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 11(4), 480–483.

Porter, G., Starcevic, V., Berle, D., & Fenech, P. (2010). Recognizing problem video game use. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 44(2), 120–128.

Rau, P. L. P., Peng, S. Y., & Yang, C. C. (2006). Time distortion for expert and novice online game players. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 9(4), 396–403.

Rehbein, F., & Borchers, M. (2009). Suechtig nach virtuellen Welten? Exzessives Computerspielen und Computerspielabhaengigkeit in der Jugend [Addicted to virtual worlds? Excessive video gaming and video game addiction in adolescents]. Kinderaerztliche Praxis, 80, 42–49.

Rehbein, F., Psych, G., Kleimann, M., Mediasci, G., & Mossle, T. (2010). Prevalence and risk factors of video game dependency in adolescence: results of a German nationwide survey. CyberPsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 13(3), 269–277.

Riggio, R. (1989). The social skill inventory manual (Researchth ed.). Palo: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and adolescent self-image. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Rosenberg, M., Schooler, C., & Schoenbach, C. (1989). Self-esteem and adolescent problems: modeling reciprocal effects. American Sociological Review, 54, 1004–1018.

Russell, D. (1996). The UCLA Loneliness Scale (Version 3): reliability, validity, and factor structure. Journal of Personality Assessment, 66, 20–40.

Salguero, R. A. T., & Moran, R. M. B. (2002). Measuring problem video game playing in adolescents. Addiction, 97(12), 1601–1606.

Seah, M., & Cairns, P. (2007). From immersion to addiction in videogames. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 22nd British HCI Group Annual Conference on People and Computers: Culture, Creativity, Interaction—Volume I, Liverpool, UK.

Shaffer, H. J., LaPlante, D. A., LaBrie, R. A., Kidman, R. C., Donato, A. N., & Stanton, M. V. (2004). Toward a syndrome model of addiction: multiple expressions, common etiology. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 12(6), 367–374.

Sherer, M., Maddux, J. E., Mercandante, B., Prentice-Dunn, S., Jacobs, B., & Rogers, R. W. (1982). The Self-Efficacy Scale: construction and validation. Psychological Reports, 51, 663–671.

Silverstone, R. (1999). Rhetoric, play, performance: revisiting a study of the making of a BBC documentary. In J. Gripsrud (Ed.), Television and common knowledge (pp. 71–90). London: Routledge.

Skoric, M. M., Teo, L. L. C., & Neo, R. L. (2009). Children and video games: addiction, engagement, and scholastic achievement. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 12(5), 567–572.

Smahel, D., Blinka, L., & Ledabyl, O. (2008). Playing MMORPGs: connections between addiction and identifying with a character. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 11(6), 715–718.

So, Y. K., Noh, J. N., Kim, Y. S., Ko, S. G., & Koh, Y. J. (2002). The reliability and validity of Korean parent and teacher ADHD rating scale. Journal of the Korean Neuropsychiatric Association, 41, 283–289.

Tangney, P. J., Baumeister, R. F., & Boone, A. L. (2004). High self-control predicts good adjustment, less pathology, better grads, and interpersonal success. Journal of Personality, 72, 272–322.

Taylor, T. L. (2006). Play between worlds. Exploring online game culture. Cambridge: MIT.

Terry, A., Szabo, A., & Griffiths, M. (2004). The exercise addiction inventory: a new brief screening tool. Addiction Research & Theory, 12(5), 489–499.

Thalemann, R., Albrecht, U., Thalemann, C., & Grüsser, S. M. (2004). Kurzbeschreibung und psychometrische Kennwerte des “Fragebogens zum Computerspielverhalten bei Kindern (CSVK). Zeitschrift für Psychologie und Medizin, 16, 226–233.

Thalemann, R., Wölfling, K., & Grüsser, S. M. (2007). Specific cue reactivity on computer game-related cues in excessive gamers. Behavioral Neuroscience, 121(3), 614–618.

The NPD Group. (2010). 2009 US video game industry and PC game software retail sales reach $20.2 billion. Retrieved November 4, 2010, from http://www.npd.com/press/releases/press_100114.html.

Thomas, N. J., & Martin, F. H. (2010). Video-arcade game, computer game and Internet activities of Australian students: participation habits and prevalence of addiction. Australian Journal of Psychology, 62(2), 59–66.

van Rooij, A. J., Schoenmakers, T. M., van de Eijnden, R., & van de Mheen, D. (2010). Compulsive Internet use: the role of online gaming and other Internet applications. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 47(1), 51–57.

Wan, C. S., & Chiou, W. B. (2006a). Psychological motives and online games addiction: a test of flow theory and humanistic needs theory for Taiwanese adolescents. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 9(3), 317–324.

Wan, C. S., & Chiou, W. B. (2006b). Why are adolescents addicted to online gaming? An interview study in Taiwan. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 9(6), 762–766.

Wan, C. S., & Chiou, W. B. (2007). The motivations of adolescents who are addicted to online games: a cognitive perspective. Adolescence, 42(165), 179–197.

Widyanto, L., & McMurran, M. (2004). The psychometric properties of the Internet Addiction Test. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 7(4), 443–450.

Williams, D., Yee, N., & Caplan, S. E. (2008). Who plays, how much, and why? Debunking the stereotypical gamer profile. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 13, 993–1018.

Wölfling, K., Thalemann, R., & Grusser-Sinopoli, S. M. (2008). Computer game addiction: A psychopathological symptom complex in adolescence. Psychiatrische Praxis, 35(5), 226–232.

Wood, R. T. A., & Griffiths, M. D. (2007). Time loss whilst playing video games: is there a relationship to addictive behaviors? International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 5, 141–149.

Yee, N. (2006a). The demographics, motivations and derived experiences of users of massively-multiuser online graphical environments. PRESENCE: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments, 15, 309–329.

Yee, N. (2006b). The psychology of MMORPGs: emotional investment, motivations, relationship formation, and problematic usage. In R. Schroeder & A. Axelsson (Eds.), Avatars at work and play: Collaboration and interaction in shared virtual environments (pp. 187–207). London: Springer.

Young, K. (1998). Caught in the net. New York: Wiley.

Young, K. (2009). Understanding online gaming addiction and treatment issues for adolescents. American Journal of Family Therapy, 37(5), 355–372.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kuss, D.J., Griffiths, M.D. Internet Gaming Addiction: A Systematic Review of Empirical Research. Int J Ment Health Addiction 10, 278–296 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-011-9318-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-011-9318-5