Abstract

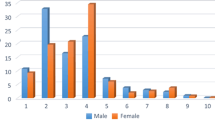

Medical claims were analyzed from 2810 military children who visited a civilian emergency department (ED) or hospital from 2000 to 2014 with behavioral health as the primary diagnosis and TRICARE as the primary/secondary payer. Visit prevalence was estimated annually and categorized: 2000–2002 (pre-deployment), 2003–2008 (first post-deployment), 2009–2014 (second post-deployment). Age was categorized: preschoolers (0–4 years), school-aged (5–11 years), adolescents (12–17 years). During Afghanistan and Iraq wars, 2562 military children received 4607 behavioral health visits. School-aged children’s mental health visits increased from 61 to 246 from pre-deployment to the second post-deployment period. Adolescents’ substance use disorder (SUD) visits increased almost 5-fold from pre-deployment to the first post-deployment period. Mental disorders had increased odds (OR = 2.93, 95% CI 1.86–4.61) of being treated during hospitalizations than in EDs. Adolescents had increased odds of SUD treatment in EDs (OR = 2.92, 95% CI 1.85–4.60) compared to hospitalizations. Implications for integrated behavioral health and school behavioral health interventions are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Fort Benning, Fort Bliss, Fort Bragg, Fort Campbell, Fort Carson, Fort Hood, Fort Irwin, Fort Knox, Fort Lewis, Fort Polk, Fort Riley, Fort Shaer, Fort Stewart, Fort Wainwright.

References

U.S. Department of Defense. Report on the impact of deployment of members of the Armed Forces on their dependent children. Washington, DC: Author; 2010.

Sogomonyan F, Cooper J. Trauma faced by children in military families: What every policymaker should know. New York, NY: Columbia University;2010.

De Pedro KMT, Astor RA, Benbenishty R, et al. The children of military service members. Review of Educational Research. 2011;81(4):566–618.

Gorman GH, Eide M, Hisle-Gorman E. Wartime military deployment and increased pediatric mental and behavioral health complaints. Pediatrics. 2010:1058–1066.

White CJ, de Burgh HT, Fear NT, et al. The impact of deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan on military children: A review of the literature. International Review of Psychiatry. 2011;23(2):210–217.

Sullivan K, Capp G, Gilreath T, et al. Substance abuse and other adverse outcomes for military-connected youth in California: Results from a large-scale normative population survey. JAMA Pediatrics. 2015;169(10):922–928.

Gorman GH, Eide M, Hisle-Gorman E. Wartime military deployment and increased pediatric mental and behavioral health complaints. Pediatrics. 2010;126(6):1058–1066.

Flake EM, Davis BE, Johnson PL, et al. The psychosocial effects of deployment on military children. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics. 2009;30(4):271–278 https://doi.org/10.1097/DBP.1090b1013e3181aac1096e1094.

Cederbaum JA, Gilreath TD, Benbenishty R, et al. Well-being and suicidal ideation of secondary school students from military families. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2014;54(6):672–677.

Gilreath TD, Cederbaum JA, Astor RA, et al. Substance use among military-connected youth: The California healthy kids survey. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2013;44(2):150–153.

Chartrand MM, Frank DA, White LF, et al. Effect of parents’ wartime deployment on the behavior of young children in military families. Archives of Pediatric & Adolescent Medicine. 2008;162(11):1009–1014.

Kelley ML. The effects of military-induced separation on family factors and child behavior. American journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1994;64(1):103–111.

Aranda MC, Middleton LS, Flake E, et al. Psychosocial screening in children with wartime-deployed parents. Military Medicine. 2011;176(4):402–407.

Astor R, De Pedro K, Gilreath T, et al. The promotional role of school and community contexts for military students. Clinical Child Family Psychological Review. 2013;16(3):233–244.

Flake EM, Davis BE, Johnson PL, et al. The psychosocial effects of deployment on military children. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics. 2009;30(4):271–278.

Gilreath TD, Astor RA, Cederbaum JA, et al. Prevalence and correlates of victimization and weapon carrying among military-and nonmilitary-connected youth in Southern California. Preventive medicine. 2014;60:21–26.

Reed SC, Bell JF, Edwards TC. Weapon carrying, physical fighting and gang membership among youth in Washington state military families. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2014.

Chandra A, Martin LT, Hawkins SA, et al. The impact of parental deployment on child social and emotional functioning: Perspectives of school staff. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2010;46(3):218–223.

Mansfield AJ, Kaufman JS, Marshall SW, et al. Deployment and the use of mental health services among U.S. Army wives. New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;362(2):101–109.

Larson M, Mohr BA, Lorenz L, et al. General and specialist health care utilization in military children of Army service members who are deployed. In: MacDermid Wadsworth S, Riggs DS, eds. Military deployment and its consequences for families. New York, NY: Springer; 2014:87–110.

Larson M, Mohr BA, Adams RS, et al. Association of military deployment of a parent or spouse and changes in dependent use of health care services. Medical Care. 2012;50:821–828.

Eide M, Gorman G, Hisle-Gorman E. Effects of parental military deployment on pediatric outpatient and well-child visit rates. Pediatrics. 2010;126(1):22.

Hisle-Gorman E, Eide M, Coll EJ, et al. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and medication use by children during parental military deployments. Military Medicine. 2014;179(5):573–578.

U.S. Department of Defense. Military health system review. Washington, DC: Author; 2014.

Wooten NR, Brittingham JA, Pitner RO, et al. Purchased behavioral health care received by military health system beneficiaries in civilian medical facilities, 2000–2014. Military Medicine. 2018;183(7–8):e278-e290.

Defense Health Agency. Evaluation of the TRICARE program: Access, cost, and quality (Fiscal Year 2015 report to Congress). Washington, DC 2015.

South Carolina Education Oversight Committee. Educational performance of military-connected children. Columbia, SC: Author; 2015.

Torreon B. U.S. periods of war and dates of recent conflicts. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service; 2015.

Belasco A. The cost of Iraq, Afghanistan, and other Global War on Terror Operations since 9/11. Washington, DC: Congresional Research Service; 2014.

Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center [AFHSC]. AFHSC surveillance case definitions. Silver Spring, MD: Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch; 2012.

Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker B, et al. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. arXiv preprint arXiv:14065823. 2014.

Seiffge-Krenke I. Stress, coping, and relationships in adolescence. Psychology Press; 2013.

Lincoln A, Swift E, Shorteno-Fraser M. Psychological adjustment and treatment of children and families with parents deployed in military combat. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2008;64(8):984–992.

Mmari KN, Roche KM, Sudhinaraset M, et al. When a parent goes off to war: Exploring the issues faced by adolescents and their families. Youth & Society. 2008;40(4):455–475.

Mmari K, Bradshaw C, Sudhinaraset M, et al. Exploring the role of social connectedness among military youth: Perceptions from youth, parents, and school personnel. Child and Youth Care Forum. 2010;39(5):351–366.

Huebner AJ, Mancini JA. Adjustments among adolescents in military families when a parent is deployed: A final report submitted to the Military Family Research Institute and the Department of Defense Quality of Life Office. Falls Church, VA: Virginia Tech, Department of Human Development;2005.

Bradshaw CP, Sudhinaraset M, Mmari K, et al. School transitions among military adolescents: A qualitative study of stress and coping. School Psychology Review. 2010;39(1):84.

Barnes VA, Davis H, Treiber FA. Perceived stress, heart rate, and blood pressure among adolescents with family members deployed in Operation Iraqi Freedom. Military Medicine. 2007;172(1):40.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA]. Behavioral health barometer: South Carolina, 2015. Rockville, MD: SAMHSA; 2015.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA]. Behavioral health barometer: United States, 2015. Rockville, MD: SAMHSA;2015.

Naeger S. Emergency department visits involving underage alcohol use: 2010 to 2013. Rockville, MD: Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration;2016.

Davis BE. Parental wartime deployment and the use of mental health services among young military children. Pediatrics. 2010:peds. 2010–2543.

National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. 2015 Profile of unique veteran users. 2016. Available at https://www.va.gov/vetdata/; accessed 15 March 2016.

Resnick A, Jacobson M, Kadiyala S, et al. How deployments affect the capacity and utilization of Army treatment facilities. Santa Monica, CA 2014.

U.S. Government Accountability Office. Army needs to improve oversight of Warrior Transition Units. Washington, DC: GAO; 2016.

Capp G, Benbenishty R, Moore H, et al. Partners at learning: A service-learning approach to serving public school students from military families. Military Behavioral Health. 2017:1–10.

Faran ME, Johnson PL, Ban P, et al. The evolution of a school behavioral health model in the US Army. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2015;24(2):415–428.

Lester P, Liang L-J, Milburn N, et al. Evaluation of a family-centered preventive intervention for military families: Parent and child longitudinal outcomes. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2016;55(1):14–24.

Moore KD, Fairchild AJ, Wooten NR, et al. Evaluating behavioral health interventions for military-connected youth: A systematic review. Military Medicine. 2017;182(11–12):e1836-e1845.

Wooten N, Tavakoli AS, Al-Barwani MB, et al. Comparing behavioral health models for reducing risky drinking among older male veterans. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2017;43(5):545–555.

Krahn D, Bartels S, Coakley E, et al. PRISM-E: Comparison of integrated care and enhanced specialty referral models in depression outcomes. Psychiatric Services. 2006;57(7):946–953.

Acknowledgements

Data are from the records of the South Carolina Revenue and Fiscal Affairs Office (SC RFA), Health and Demographics, whose authorization to release these data does not imply endorsement of this study or its findings by either the Division of Research and Statistics or the Data Oversight Council. The authors acknowledge programming assistance from Mr. Chris Finney, SC RFA, Health and Demographics Division, in creating the data extract used in this study and research assistance from Tamara L. Grimm, MSW.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA #K01DA037412, PI: Nikki R. Wooten, PhD).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Wooten is a lieutenant colonel in the U.S. Army Reserves and Mr. Moore is a lieutenant junior grade in the U.S. Naval Reserves, but neither conducted this study as a part of their official military duties. All other authors report no conflicts of interest. The opinions and assertions herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official views of the Department of Defense, SC RFA, NIDA, or the National Institutes of Health.

Presentation Information

This study was presented as an oral presentation at the annual meeting of the Society for Social Work and Research, New Orleans, LA, January 14–17, 2017.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wooten, N.R., Brittingham, J.A., Sumi, N.S. et al. Behavioral Health Service Use by Military Children During Afghanistan and Iraq Wars. J Behav Health Serv Res 46, 549–569 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11414-018-09646-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11414-018-09646-0