Abstract

Adolescents living in single-mother households are more likely to have behavioral health conditions, but are less likely to utilize any behavioral health services. Using nationally representative mother-child pair data pooled over 6 years from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, the study finds that when single mothers were uninsured, their adolescent children were less likely to utilize any behavioral health services, even when the children themselves were covered by insurance. The extension of health coverage under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) to uninsured single mothers could improve the behavioral health of the adolescent population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The expansions in insurance coverage under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) are expected to increase the number of users of mental health and substance abuse services.1 – 3 Although much of the focus of the literature on the ACA and behavioral health services utilization has been on adults, less is known about adolescents (ages 12–17). An estimated 10% of adolescents (2.8 million) had a major depressive episode (MDE) in the past 12 months, and 5% of adolescents (1.3 million) had a substance use disorder (SUD).4 Given that one of the most common barriers to behavioral health treatment among adolescents is cost,5 increased access to insurance coverage under the ACA can be expected to increase behavioral health services utilization among adolescents, especially those living in a single-mother household—a group that has risen dramatically in size (from 4% in 1970 to 24% in 2010) over the past four decades.6

A substantial number of adolescents (approximately 34 million) have gained health insurance coverage through the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) in 1997, the CHIP reauthorization in 2015, and the recent expansions in Medicaid coverage under the ACA.7 , 8 These programs have given them access to a range of mental health and substance abuse services. In addition, an estimated 4.2 million uninsured adolescents will gain coverage through the ACA7as a result of subsidies to purchase private insurance, prohibition of pre-existing condition exclusions, expanded Medicaid eligibility, and parity requirements. While the number of adolescents with insurance has increased, it is unclear what factors may affect adolescents’ utilization of behavioral health services. Research suggests that parents of uninsured children were more likely to report unmet mental health needs for their children than did parents of insured children.9

Children and adolescents in single-mother families are more likely to have mental health conditions than those living with both biological parents.10 – 12 Almost one-quarter (24%) of the 75 million children in the USA under the age of 18 live in a single-mother family, and over half of them have low income.6 Prior research has shown that children in single-parent families are less likely to receive certain types of preventive care and also less likely to have a usual source of care, compared to two-parent families.13 , 14 Many single-mother families have limited financial resources available to cover children’s education, child care, and health care costs;15 , 16 on average, poor families live further away from health care facilities, have less access to transportation, and less flexibility in their jobs to attend to their children’s health care.13 Children of single mothers are thus likely to have lower health services use. Indeed, studies have found that children of single mothers were more likely to have unmet health care needs than children in two-parent families, and they were also more likely to be in fair or poor health compared to children in two-parent families.12 , 17 – 19 Single mothers might also face additional challenges in obtaining treatment for their children compared to married mothers, such as not having adequate time to take the child to appointments.

However, the role of insurance in behavioral health services utilization among children in single-mother households has not been explored. One study found that for insured children, parental insurance status was independently associated with children’s use of health care services.20 Specifically, insured children in that study with at least one parent who lacked coverage were more likely to go without necessary health care and preventive counseling services. While it examined parental insurance status, however, that study did not focus on single mothers, nor did it explore behavioral health services. In addition, research on the influence of health insurance coverage on adolescents’ utilization of behavioral health services focused only on the adolescents’ own health insurance status.5 , 9 , 15 Research has shown that parental behaviors and characteristics, especially those of mothers, are a significant predictor of many adolescent health outcomes, including those related to substance abuse and mental health.21 , 22 Thus, it is likely that mothers’ health insurance status might be an important predictor of adolescent behavioral health treatment utilization independent of the health insurance status of the adolescents themselves.

This paper contributes to the literature on health insurance and behavioral health treatment utilization in several important ways. First, the paper examines the influence of single mothers' health insurance on adolescents' utilization of behavioral health services. This is an important but omitted area in the literature, especially given estimates that have shown persistently high lack of insurance rates among single parents in recent years.23 Second, the study utilized a unique nationally representative data set of mother and adolescent pairs. The data made it possible to control for both mother and child characteristics in the empirical model, resulting in more robust estimates of the impact of single mothers’ health insurance status on behavioral health utilization of their adolescent children.

Methods

Dataset

This study utilized parent-child pair data from the 2008–2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), a nationally representative survey of the non-institutionalized population in the USA conducted annually by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). The NSDUH collects detailed information on use of alcohol and illicit drugs, mental health, and behavioral health treatment utilization. Each year, NSDUH also samples pairs of one parent and an adolescent who live in the same household. This pair-data component of the NSDUH is done by using a preprogrammed algorithm selection, which allows NSDUH to select either one or two sample persons for interview among all eligible household members and contains data on spouse or partner pair, parent-child pair, and sibling pair.24 , 25 Analyses for the present study were conducted on approximately 700 (unweighted) adolescents (ages 12 to 17) with a behavioral health condition (MDE or SUD), living in a single-mother household, whose biological mother was also selected for and completed the interview. The sampling algorithm of selecting a maximum of two persons from any household precludes the possibility of obtaining information from an adolescent and both parents. In addition, since the focus of the analysis is to estimate the impact of mothers' health insurance status on behavioral health services utilization among adolescents, the multivariable analysis is limited to insured adolescents only (N = 600). It is important to note that there are no significant differences between insured and uninsured adolescents in the sample. Comprehensive information on the NSDUH data collection methods and survey design has been made available by SAMHSA.4 , 24

Measures

The NSDUH asks respondents questions intended to assess symptoms of MDE and SUD during the past year, using the criteria specified within the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.26 MDE is defined as a period of at least 2 weeks when the adolescent experienced a depressed mood or loss of interest or pleasure in daily activities, and other additional symptoms, and SUD includes symptoms such as withdrawal, tolerance, use in dangerous situations, trouble with the law, and interference in major obligations at work, school, or home during the past year associated with alcohol use or any illicit drug use disorder.

In order to estimate the impact of mothers' health insurance status on adolescent behavioral health treatment utilization, the study used three dichotomous measures of behavioral health treatment during the year as outcome variables in the study: (1) any mental health treatment, (2) any substance abuse treatment, and (3) any behavioral health (mental health or substance abuse) treatment. Mental health treatment as available in the NSDUH refers to the use of one or more of the following types of services during the year: outpatient treatment services, inpatient treatment services, and use of any psychotropic medication. Substance abuse treatment refers to the use of any outpatient or inpatient treatment services during the year (including substance use treatment at a private physician’s office and substance abuse-related emergency room visit).

The primary independent variable of interest in the empirical models was the health insurance status of the biological mother. The coefficient on this variable estimated how the mothers' insurance status was related to the behavioral health treatment of the adolescent with a behavioral health disorder, irrespective of the adolescents' own health insurance status. Health insurance status was measured by a categorical variable with four mutually exclusive categories: private insurance, Medicaid (including those with dual eligibility also enrolled in Medicare), uninsured, and other insurance (e.g., veteran’s insurance, TRICARE, etc.). Other parental correlates included as control variables in this study were mothers' behavioral health status (any mental illness, SUD, both, or none), indicators of receiving mental health treatment and substance abuse treatment, general self-rated health (excellent, very good, good, or fair/poor), employment (full-time, part-time, unemployed, or other, which included students, persons keeping house or caring for children full time, retired or disabled persons, or other persons not in the labor force), education (less than high school, high school graduate, some college, or college graduate), and federal poverty status (less than 138% of the federal poverty line (FPL), 138% to 400% FPL, or 400% FPL or more). The Andersen behavioral model of health care utilization was used to guide the selection of covariates.27

Adolescent correlates included in this study were age, gender, race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, non-Hispanic other, or Hispanic), general self-reported health status, and whether the adolescent had public insurance. These variables were also selected based on the Andersen behavioral model of health care utilization.27

Data Analysis

Three separate logistic regressions were estimated to calculate odds ratios for adolescent and mother correlates of (1) any mental health treatment, (2) any substance abuse treatment, and (3) any behavioral health (mental health or substance abuse) treatment by adolescents. All estimates were weighted to account for NSDUH’s complex survey design and to yield national estimates for the subset of adolescents with a behavioral health disorder living in a single biological mother household (weighted pooled N ≈ 1 million).

Results

As shown in Table 1, approximately 44% of adolescents with a behavioral health disorder living in a single-mother household received some form of behavioral health treatment. Among adolescents with a behavioral health disorder living in a single-mother household, the rate of mental health treatment utilization was substantially higher than substance abuse treatment (42 versus 6%). Only 7% of the adolescents with a behavioral health disorder were uninsured, and Medicaid was the most frequent source of coverage (48%), followed by private insurance (35%), and other type of insurance (10%). Among mothers, private insurance coverage rates were similar to those of adolescents, but the rate of Medicaid coverage was lower (30%). However, the rate of having no insurance was higher (26%) among the mothers compared to the adolescents. In terms of national estimates, this translates to about a quarter of a million single mothers of adolescents with behavioral health conditions not having any health insurance. Approximately 55% of the mothers in the sample did not have any behavioral health disorder; 55% were also employed full time. However, a majority of them (54%) had incomes under 138% of the FPL. Among the mothers, the most common education category was completed high school only (39%).

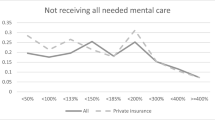

As indicated previously, since the focus of the study is to understand the impact of the mothers’ insurance status on behavioral health treatment of the adolescents, regardless of the adolescents’ own insurance status, the analysis concentrates only on insured adolescents, resulting in an unweighted sample size of 600. By looking at patterns of behavioral health treatment (Table 2) among insured adolescents in the study sample, it is evident that behavioral health services utilization is higher among adolescents whose mother is also insured. Specifically, Table 2 shows that among insured adolescents with a behavioral health disorder, the rate of treatment utilization is 50% when the mother is insured, as compared to 27% when the mother is uninsured. For mental health treatment, the rate of utilization is 56% when the mother is insured and 44% when the mother is uninsured. The difference in treatment utilization is particularly pronounced for substance abuse treatment, where utilization is only 2% when the mother is uninsured and is 16% when the mother is insured.

Table 3 presents estimates from the three logistic regression models that account for an extensive set of control variables. Estimates indicate that among insured adolescents, those whose mothers have private insurance or Medicaid had between 2 to 3 times the odds of obtaining any behavioral health treatment when compared to those with uninsured mothers (p < 0.001). For mental health treatment, having a mother with private insurance or Medicaid was also associated with between 2 and 3 times the odds of obtaining mental health treatment compared with having a mother without any health insurance (p < 0.001). Substance abuse treatment exhibited the largest impact of mothers' insurance, with odds ratios of approximately 19 and 23, respectively, for mothers' private insurance and Medicaid coverage (p < 0.01).

As indicated previously, all the adolescents in the multivariate analysis had some type of health insurance; however, including adolescents who are uninsured in the analysis resulted in a similar but larger estimate of the impact of mothers’ insurance, demonstrating the robustness of the findings (results not reported but available upon request). Other correlates that had a significant impact on adolescent behavioral health treatment include adolescents' race and gender. Maternal characteristics, such as whether the mother had obtained any mental health treatment and whether she was employed part-time, also had a significant impact on behavioral health treatment among adolescents. However, these correlates were only statistically significant for any behavioral health treatment and any mental health treatment models, not for the any substance abuse treatment model.

Discussion

While the effect of health insurance coverage on utilization of behavioral health treatment by adolescents has been studied previously,5 , 9 past research has focused on insurance coverage of the children rather than on that of the parents. The current study is the first to empirically examine the relationship of single mothers’ health insurance coverage on behavioral health services utilization by their adolescent children. Utilizing a unique data set of mother and child pairs that enabled us to control for the insurance status of the adolescent while examining the insurance status of the mother, the current study found that when single mothers were uninsured, their adolescent children had lower odds of utilizing behavioral health services, even when the children themselves were covered by insurance. More specifically, the findings showed that among insured adolescents with a behavioral health disorder, the odds of any behavioral health treatment utilization were between 2 and 3 times higher when the mother had private insurance or Medicaid compared to when the mother was uninsured. The impact of mothers' health insurance was larger for adolescents' substance abuse treatment compared to mental health treatment. In the analysis, substance use-related emergency department visits are included as part of SUD treatment. Although such visits might not constitute ideal treatment for SUD, they were included in the analysis because they are routinely included in reports issued by federal agencies as well as the general literature describing utilization of substance abuse treatment.28 There is also emerging evidence of the effectiveness of brief interventions for substance abuse delivered in emergency department settings.29 , 30

Another important result of the analysis is the association of mothers' mental health treatment utilization with adolescents’ behavioral health treatment and mental health treatment in particular. This may imply that when mothers are familiar with the behavioral health services themselves, they are also more likely to seek treatment for their adolescent child. However, it is important to note that utilization of SUD treatment by the mothers was not associated with substance abuse treatment by the adolescent, which is a topic that could be an important direction for future research. In addition, the results also showed that non-Hispanic Black adolescents had lower odds of receiving behavioral health treatment. This finding is consistent with the literature documenting lower levels of behavioral health treatment utilization among minority populations.31 Female adolescents, on the other hand, had higher odds of receiving behavioral health treatment.

Single mothers are disproportionately unemployed or working in low-wage jobs with few health benefits.6 The expansion in insurance coverage resulting from the implementation of the ACA is expected to result in higher rates of insurance among single mothers. Behavioral health is considered an essential health benefit under the ACA, and the benefits of the ACA clearly extend not only to the individual with newly acquired health coverage (single mothers in this case), but also to their children.32 Evidence from this study indicates that coverage expansion could be very important for this group, especially since health insurance coverage is determined more at the family level and it is generally the parents who make decisions regarding treatment utilization of their children.20 It is important to note that parents may have various insurance coverage options under the ACA (e.g., Medicaid expansion, private insurance purchased through the exchanges). This study uses data that predate the full implementation of the policies that made these options available. Future research could examine how behavioral health treatment utilization differs depending on the type of coverage obtained.

Despite the strength of the empirical model used in this study, the results should be interpreted in light of a few limitations. First, the data are cross-sectional. Consequently, the results cannot be interpreted as causal, even though the study was able to account for the insurance status of both the mother and the child. Second, it is possible that mothers' insurance is capturing other factors which are not included in the model but which are correlated with insurance. The study tries to control for other maternal characteristics that can influence treatment seeking of their adolescent children by including variables for mothers' education, employment, income, health, and utilization of behavioral health services in the model. Exploratory qualitative research is needed to better understand the impact of health insurance on treatment utilization. Also, there is evidence that single-mother families are more likely than two-parent families to have a grandmother or other adult female relative in the household.17 However, it is not clear what effect, if any, the presence of other female relatives may have on treatment-seeking behavior. Third, measures were not available in the data set to assess the reasons why the health insurance of the mothers might affect adolescent utilization of behavioral health treatment (e.g., the mothers' attitudes and beliefs regarding behavioral health treatment are not captured in the data).

Implications for Behavioral Health

Utilizing a unique nationally representative data set of mother and adolescent pairs, this study documents the importance of health insurance for single mothers in increasing treatment utilization among children with a behavioral health disorder. The findings provide further insight into why adolescents with a behavioral health disorder in single-mother households may have lower utilization of both mental health and substance abuse treatment services, despite having health insurance themselves. Extending health coverage to uninsured single mothers and achieving parity of coverage for behavioral health services is expected to improve the behavioral health of this adolescent population.

Despite high rates of labor force participation among single mothers, more than one-fourth (27%) of single mothers did not have health insurance prior to the full implementation of the ACA.6 Thus, if health insurance coverage for single mothers increases following the implementation of ACA, it might benefit not only the single mothers themselves, but also their children.

Examination of the mechanism by which parental health insurance increases utilization of an adolescent’s behavioral health services could be an important direction for future studies. Another important topic for future research is whether the mechanism through which mothers obtain coverage (e.g., Medicaid expansion, private insurance) impacts the utilization of behavioral health services by their adolescent children.

References

Ali MM, Teich J, Woodward A, et al. The implications of the Affordable Care Act for behavioral health services utilization. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2016; 43(1): 11 – 22.

Ali MM, Teich J, Mutter R. The role of perceived need and health insurance in substance use treatment: Implications for the Affordable Care Act. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2015; 54: 14 – 20.

Mark TL, Wier LM, Malone K, et al. National estimates of behavioral health condition and their treatment among adults newly insured under the ACA. Psychiatric Services. 2015; 66(4): 426 – 429.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Substance use and mental health estimation from the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Overview of findings. Rockville: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics & Quality, 2014.http://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUHresultsPDFWHTML2013/Web/NSDUHresults2013.htm. Published September 4, 2014. Accessed 23 April 2015.

DiCola LA, Gaydos LM, Druss BG, et al. Health insurance and treatment of adolescents with co-occurring major depression and substance use disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2013; 52(9): 953 – 960.

Population Research Bureau. U.S. children in Single-Mother Families. http://www.prb.org/Publications/Reports/2010/singlemotherfamilies.aspx. Published May 1, 2010. Accessed 23 April 2015.

Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. The Affordable Care Act and adolescents. http://aspe.hhs.gov/health/reports/2013/Adolescents/rb_adolescent.cfm Published August 1, 2013. Accessed 23 April 2015.

Selden T, Dubay L, Miller GE, et al. Many families may face sharply higher costs if public health insurance for their children is rolled back. Health Affairs. 2015; 34(4): 697-706.

DeRinge LA, Porterfield S. The influence of health insurance on parent’s reports of children’s unmet mental health needs. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2009; 13: 176 – 186.

Reczek, C., Spiker, R., Liu, H. Crosnoe, R. Family Structure and Child Health: Does the Sex Composition of Parents Matter. Demography. In-Press.

Bode, A.A., George, M.W., Weist, M.D. et al. The Impact of Parent Empowerment in Children’s Mental Health Services on Parenting Stress. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2016; 25: 3044.

Bramlett MD, Blumberg SJ. Family Structure and Children’s Physical and Mental Health. Health Affairs. 2007; 26(2): 549 – 558.

Gorman BK, Braverman J. Family structure differences in health care utilization among U.S. chldren. Social Science and Medicine. 2008; 67:1766-1775.

Blackwell DL. Family structure and children’s health in the United States: Findings from the National Health Interview Survey, 2001-2007. National Center for Health Statistics, 2008

Clarke TC, Arheart KL, Muenning P, et al. Health care access and utilization among children of single working and nonworking mothers in the United States. International Journal of Health Services. 2011; 41(1): 11 – 26.

Ali, MM., Ajilore, O. Can marriage reduce risky health behavior for African-Americans? Journal of Family and Economic Issues. 2011; 32(2): 191 – 203.

Heck KE, Parker JD. Family Structure, Socioeconomic Status, and Access to Health Care for Children. Health Services Research.2002; 37:1 .

Langton CE, Berger LM. Family Structure and Adolescent Physical Health, Behavior, and Emotional Well-Being. Social Services Review. 2011; 85(3)323-357.

Krueger PM, Jutte DP, Franzini L, et al. Family structure and multiple domains of child well-being in the United States: a cross-sectional study. Population Health Metrics.2015;13:6.

DeVoe JE, Marino M, Angier H, et al. Effect of expanding Medicaid for parents on children’s health insurance coverage: Lessons from the Oregon experiment randomized trial. JAMA Pediatrics. 2015; 169(1):e143145.

Halfon N, Hochstein M.Life course health development: an integrated framework for developing health, policy, and research. Milbank Quarterly. 2002;80(3):433-479.

Harold GT, Rice F, Hay DF, et al. Familial transmission of depression and antisocial behavior symptoms: disentangling the contribution of inherited and environmental factors and testing the mediating role of parenting. Psychological Medicine. 2011;41(6):1175-1185.

Urban Institute. Health insurance coverage for parents under the ACA as of September 2014. http://hrms.urban.org/quicktakes/Health-Insurance-Coverage-for-Parents-as-of-September-2014.html.Published September 1, 2014. Accessed 23 April 2015.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Questionnaire Dwelling Unit-Level and Person Pair-level Sampling Weight-Calibration. Rockville: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics & Quality, 2014.

Ali, MM., Dean, D., Hedden, S. The influence of parental comorbid mental illness and substance use disorder on adolescent substance use disorder. Addictive Behaviors. 2016;59:35-41.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-IV) (4th ed.). Washington, DC 1994.

Andersen RM. Revisiting the Behavioral Model and Access to Medical Care: Does it Matter? Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995; 36(1), 1. doi:10.2307/2137284.

Saloner B, Karthikeyan S. changes in substance abuse treatment use among individuals with opioid use disorders in the United States, 2004-2013. JAMA. 2015; 314(14): 1515 – 1517.

Cunningham RM, Chermack ST, Ehrlich PF, et al. Alcohol interventions among underage drinkers in the ED: A randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2015;136(4):e783-93.

Deluca P, Coulton S, Alam MF, et al. Linked randomized controlled trials of face-to-face and electronic brief intervention methods to prevent alcohol related harm in young people aged 14-17 years presenting to Emergency Departments (SIPS junior). BMC Public Health.2015; 15:345.

Cummings JR, Wen H, Bruss BJ. Racial/Ethnic Differences in Treatment for Substance Use Disorder among U.S. Adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2011; 50(12): 1265 – 1274.

National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL). Children’s Health Insurance program overview. http://www.ncsl.org/research/health/childrens-health-insurance-program-overview.aspx. Published April 17, 2015. Accessed 23 April 2015.

Acknowledgements

The views expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) or the US Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ali, M.M., Teich, J.L. & Mutter, R. The Impact of Single Mothers’ Health Insurance Coverage on Behavioral Health Services Utilization by Their Adolescent Children. J Behav Health Serv Res 45, 46–56 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11414-017-9550-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11414-017-9550-2