Abstract

The aim of the current study was to examine whether moral disengagement and defender self-efficacy at individual level and collective efficacy to stop peer aggression at classroom level were associated with defending and reinforcing in school bullying situations in late childhood. Self-reported survey data were collected from 1060 Swedish students from 70 classrooms in 29 schools. Multilevel analysis found that greater defender self-efficacy at individual level and collective efficacy to stop peer aggression at classroom level were associated with greater defending. We also found that greater moral disengagement and less (but very weakly) defender self-efficacy at individual level and less collective efficacy to stop peer aggression at classroom level were associated with greater reinforcing. The positive relationship between moral disengagement and reinforcing and the negative relationship between defender self-efficacy and reinforcing were less strong in classroom high in collective efficacy to stop aggression.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Bullying, defined as repeated inhumane, aggressive or offensive actions directed at individuals who are disadvantaged or less powerful in relation to the perpetrator(s) (Jimerson et al. 2010). Victims are at a heightened risk of developing internalizing and externalizing problems (Fisher et al. 2016; Gini et al. 2018a), including negative educational outcomes such as school absence and lower academic achievement (Fry et al. 2018; Nakamoto & Schwartz 2010). Bullying is a social phenomenon that occurs in and is influenced by social context (Hymel et al. 2015; Salmivalli 2010). Peers are present as witnesses or bystanders in the vast majority of school bullying events (Craig et al. 2000; O’Connell et al. 1999). A bystander is defined as any student who witnesses a bullying incident (Polanin et al. 2012). Salmivalli et al. (1996) identified four participant roles that students who witness bullying may have in the bullying process: assistants are those who join the ringleader bullies and participate in the bullying, reinforcers support and provide positive feedback to bullies by cheering and laughing, outsiders remain passive or neutral and try to stay outside, and defenders take sides with the victims by helping, supporting, and comforting them. How peers react and act as bystanders matters. At classroom level, reinforcing has been positively linked with greater bullying (Kärnä et al. 2010; Nocentini et al. 2013; Salmivalli et al. 2011; Thornberg and Wänström 2018), whereas defending has been associated with less bullying (Kärne et al. 2010; Nocentini et al. 2013; Salmivalli et al. 2011). These two bystander responses are two opposite ways to take sides in bullying situations (Pöyhönen et al. 2012), and demonstrate the moral agency students as bystanders may or may not, manifest in school bullying.

Although qualitative interview studies indicate that students think that in general, they should intervene and help the victim when witnessing bullying (Chen et al. 2016; Forsberg et al. 2014, 2018; Thornberg et al. 2018), a range of individual and contextual factors might facilitate as well as inhibit their moral agency as bystanders, and some of those are also recognized by the students themselves (Chen et al. 2016; Forsberg et al. 2014, 2018; Thornberg et al. 2018). In the current study, we examined bystanders’ moral agency in school bullying, and we have delimited our focus on moral disengagement and defender self-efficacy at the individual level and collective efficacy to stop peer aggression at classroom level.

1.1 Social-cognitive theory

According to the social-cognitive theory (Bandura 1999, 2002, 2016), moral agency is both inhibitive and proactive. Whereas the former refers to the ability to refrain from behaving inhumanely, the latter, “grounded in a humanitarian ethic, is manifested in compassion for the plight of others and efforts to further their well-being, often at personal costs” (Bandura 2016, pp. 1–2). In a school bullying context and from a bystander position, the ability to refrain from reinforcing bullying and the capacity to defend the victim can thus be considered as manifestations of moral agency. However, people do not always regulate their actions in accordance with humanitarian ethics (Bandura 2016). According to the social-cognitive theory, moral agency is related to the so-called triad codetermination, which refers to the interplay between personal, behavioral, and environmental influences in the motivation and regulation of behavior. There are many social and psychological processes that could deactivate self-regulation, disengage moral self-sanction from inhumane conduct, inhibit humane, moral and prosocial behaviors, and create incitements or pressure to act inhumanely (Bandura 2016).

1.1.1 Moral disengagement

Within the social-cognitive theory (Bandura 1999, 2002, 2016), moral disengagement refers to a set of self-serving cognitive distortions by which self-regulation based on moral standards can be deactivated and moral self-sanctions can be disengaged, which in turn facilitates inhumane behavior without any feelings of remorse or guilt. Moral disengagement and its mechanisms are learned through social interactions with others, and can develop into habits or dispositions. Examples of moral disengagement mechanisms are moral justification (i.e., using worthy ends or moral purposes to excuse pernicious means), diffusion of responsibility (i.e., diluting personal responsibility because other people are also involved), disregarding or distorting the negative or harmful consequences of the actions, and blaming the victim (i.e., believing that the victim deserves his or her suffering). Moral disengagement is associated with greater aggression, including bullying (for a meta-analyses, see Gini et al. 2014; Killer et al. 2019), assisting and reinforcing (Gini 2006; Sjögren et al. 2020; Thornberg and Jungert 2013), and less defending (Doramajian and Bukowski 2015; Gini 2006; Gini et al. 2018b; Mazzone et al. 2016; Obermann 2011; Pozzoli et al. 2016; Thornberg and Jungert 2013, 2014; Thornberg et al. 2015, 2017; for a meta-analysis, see Killer et al. 2019; for exceptions, see Barchia and Bussey 2011b; Sjögren et al. 2020) in bullying and peer aggression among students.

1.1.2 Defender self-efficacy

Moral agency is also dependent on the belief in one’s capacities in acting in accordance with moral standards (Bandura 2016). Perceived external and internal constraints can lead to low outcome expectations and distrust in one’s ability to perform, and thus inhibit moral behavior. The concept self-efficacy refers to the beliefs in one’s capacities to organize and execute the lines of action required to produce given attainments, and whereas high self-efficacy motivates action if the action is in line with personal standards and goals, low self-efficacy will inhibit action (Bandura 1997). Bandura (1997) argues that people’s beliefs in their capacity to act efficiently vary across different domains of activities, and therefore, to understand moral agency of bystanders in bullying situations (i.e., to defend the victims), we need to examine their defender self-efficacy.

Defender self-efficacy could be defined as the belief in one’s capacities to successfully intervene in bullying or peer aggression to defend a victim (Thornberg et al. 2017) and has, in accordance with the social-cognitive theory (Bandura 1997), been associated with greater defender behavior (Barchia and Bussey 2011b; Doramajian and Bukowski 2015; Peets et al. 2015; Pöyhönen et al. 2010, 2012; Thornberg and Jungert 2013; Thornberg et al. 2017; van der Ploeg et al. 2017). The possible association between defender self-efficacy and reinforcing is still rather unknown since only a few studies have explored this. One study has found defender self-efficacy to be associated with less pro-bullying behavior (i.e., assisting and reinforcing; Thornberg and Jungert 2013). In another study (Pöyhönen et al. 2012), defender self-efficacy was significantly and negatively correlated with reinforcing but when defender self-efficacy was included together with other variables within a regression analysis, the association became insignificant. However, in the same regression analysis, the less the students expected bullying to decrease and that the victim would feel better as a consequence of defending, the more likely they were to reinforce the bully. Nevertheless, more research is needed to examine the possible negative relationship between defender self-efficacy and reinforcing in school bullying among students.

1.1.3 Collective efficacy to stop peer aggression

The bystander literature within social psychology has revealed that the presence of other bystanders can inhibit helping behavior (“bystander effect” and “social inhibition”) as well as facilitating helping behavior (“social facilitation”) toward people in need, depending on factors such as how the other bystanders behave in the emergency situation and shared social norms and beliefs in the group (Abbate and Ruggieri 2016; Fischer et al. 2011; Garcia et al. 2009). Although social-cognitive theory assumes that perceived self-efficacy is the foundation of human agency (Bandura 1997), “people do not live in social isolation, nor can they exercise control over major aspects of their lives entirely on their own” (Bandura 1997, p. 477). Social-cognitive theory extends the concept of human agency to also include collective agency in which people are interdependent, pool their competence and resources, and work together to solve problems and gain common goals (Bandura 1997; Fernández-Ballesteros et al. 2002).

Collective efficacy is an emergent group-level attribute (Bandura 1997; Fernández-Ballesteros et al. 2002) that reflects a group’s capacity to work together to produce given attainments (Hymel et al. 2015). Bandura (1997) defines it as “a group’s shared beliefs in its conjoint capabilities to organize and execute the courses of action required to produce given levels of attainments” (p. 477), and has positive effects on group performance (for a review, see Fernández-Ballesteros et al. 2002). Collective efficacy to stop peer aggression is a specific kind of perceived collective efficacy and refers to the shared beliefs in the ability of students and teachers to work together to stop peer aggression in schools (Barchia and Bussey 2011a, b). So far, only a few studies have examined collective efficacy to stop peer aggression. Individually perceived collective efficacy to stop aggression has been found to predict less aggression (Barchia and Bussey 2011a) and greater defending (Barchia and Bussey 2011b) among Australian adolescents. Further research is needed to examine collective efficacy as a group characteristic (e.g., classroom level) and its possible associations with various bystander behaviors in school bullying, including reinforcing and defending.

1.2 Current study

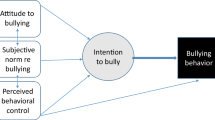

The aim of the current study was to examine whether moral disengagement and defender self-efficacy at the individual level and collective efficacy to stop peer aggression at the classroom level were associated with defending and reinforcing in school bullying situations in late childhood. First, we hypothesized that moral disengagement would be associated with greater reinforcing and less defending. Second, we hypothesized that defender self-efficacy would be associated with greater defending and less reinforcing. Third, we hypothesized that collective efficacy to stop peer aggression at the classroom level would be associated with greater defending and less reinforcing.

Because social-cognitive theory (Bandura 1997, 2016) emphasize that behaviors are produced by interdependent associations between individual and contextual factors (the triad codetermination manifested as the interplay between personal, behavioral, and environmental influences), we also assumed we would find, at least some, cross-level interaction effects. However, because of the lack of previous empirical research, the literature did not offer us any clear hypotheses to deduce and test. Possible cross-level interactions between moral disengagement and collective efficacy, and between defender self-efficacy and collective efficacy on defending and reinforcing were therefore examined in an exploratory manner.

Gender and age were included as covariates. Numerous studies have revealed that girls score higher than boys on defending (Barchia and Bussey 2011b; Doramajian and Bukowski 2015; Gini et al. 2015; Obermann 2011; Pöyhönen et al. 2010, 2012; Pozzoli and Gini 2012; Thornberg and Jungert 2013; Thornberg et al. 2015; Trach et al. 2010). Some studies have, in addition, found that boys score higher than girls on reinforcing (Pöyhönen et al. 2012; Salmivalli and Voeten 2004; Thornberg and Jungert 2013). Based on previous findings, we hypothesized that girls would be more engaged in defending than boys, whereas boys would be more engaged in reinforcing than girls. Concerning age, previous research has revealed that defending tends to decline with age (Barchia and Bussey 2011; Pöyhönen et al. 2010; Pozzoli and Gini 2012; Rigby and Johnson 2006; Salmivalli and Voeten 2004; Trach et al. 2010), whereas reinforcing tends to increase with age (Pöyhönen et al. 2012; Salmivalli and Voeten 2004). We therefore hypothesized that age would be negatively associated with defending and positively associated with reinforcing.

2 Methods

2.1 Participants

The participants in the current study consisted of 1060 students (487 [46%] girls, 573 [54%] boys) from 70 classrooms in 29 schools located in small villages in the countryside and in different neighborhoods of midsize cities in the middle and southern parts of Sweden. The age range of the sample was 10–14 years old (M = 11.63, SD = .83). Socio-economic status was not directly measured in the study, but the sample of the public schools represented a wide range of socio-geographic locations and socio-economic statuses. The vast majority of the participants were of Swedish ethnicity, and only a small minority (6%) had a foreign background, that is, either they had been born in another country or both their parents were born in another country. The original sample consisted of 1416 students (666 girls [47%] and 750 boys [53%]; thus, the gender ratio was found to be equivalent between the original sample and the final sample). Three-hundred-and-fifty-six of those did not participate for various reasons. In the study, we excluded 256 students because their parents did not grant an active consent, 58 students were absent at the data collection session, 16 students did not want to participate, and five students were excluded due to difficulties to participate. In addition, 21 students were dropped because they did not fill out any information in at least one of the scales included in the current study. We obtained parental consent and student consent from all 1060 participating students.

Some students did not fill out all the items in the scales. 1048 students had complete information on defending (15 students had 1 item missing), 1044 had complete information on reinforcing (21 students had 1 item missing), 978 on moral disengagement (77 students had 1 item missing), 1058 on defender self-efficacy (8 students had 1 item missing), and 1026 on collective efficacy (43 students had 1 item missing). Because most of the students had complete information, or only one item missing on the scales, we used all the available item responses when constructing the index scores for each student. Our analyses were thus based on all 1060 students who had complete (or incomplete) information on the measured variables included in the present study.

2.2 Procedure

The study received ethical approval from the Regional Ethical Review Board at Linköping. The participants completed a questionnaire in their regular classroom. The third, fourth and fifth authors were individually present in the classrooms during the survey administration. They explained the study procedure, reassured students that their participation was voluntary and confidential, and assisted the participants who needed help. The participants responded anonymously to the questionnaire.

2.3 Measures

Socio-demographic scale Participants completed a socio-demographic scale that included questions about their age (i.e., “How old are you?” followed by, “I’m… years and… months old”), gender (0 = girl, 1 = boy), and Swedish versus foreign background (i.e., “Were you born in Sweden? Was your mother born in Sweden? Was your father born in Sweden?”). Participants who reported that they were born in another country and/or that both their parents were born in another country were categorized with foreign background.

Moral disengagement An 18-item moral disengagement in bullying scale (Thornberg and Jungert 2014) was used to measure the tendency to morally disengage in bullying situations (e.g., “It’s okay to harm another person a couple of times a week if you do that to protect your friends”, “If my friends begin to bully a classmate, I can’t be blamed for being with them and bullying that person too”, “Saying mean things to a certain person a couple of times a week doesn’t matter. It’s just about joking a little with the person”, “If you can’t be like everybody else, you have to blame yourself if you get bullied”). Response options for each item were on a seven-point scale (1 = “strongly disagree” to 7 = “strongly agree”). The 18 items were averaged into one scale score. A CFA model with one factor was estimated with DWLS in R using the Lavaan package, indicating good fit of the model (\(\chi^{2}_{\text{Robust}} (135)\) = 966.385, p < .001, RMSEARobust = .053, (90% C.I.: .050; .056), CFIRobust = .926, SRMRRobust = .086, Cronbach’s α = .87).

Defender self-efficacy A 5-item scale was used to measure defender self-efficacy (Thornberg et al., 2017). Participants were asked to estimate how true the following statements were, starting with, “I feel that I’m very good at…” which was then followed by the five items (e.g., “…helping students who are bullied”, “…telling students who are bullying someone to stop doing that”, “…getting a group to stop making up stories/lying about another student”. Response options for each item were on a seven-point scale (1 = disagree to 7 = agree). The average of these five items was computed for each student. A one factor model indicated good fit (\(\chi^{2}_{\text{Robust}} (5)\) = 12.414, p = .030, RMSEARobust = .017 (90% C.I.: .000; .030), CFIRobust = 1.000, SRMRRobust = .013, Cronbach’s α = .90).

Collective efficacy to stop peer aggression A Swedish version (Wänström et al. 2017) of Barchia and Bussey’s (2011a, b) 10-item scale was used to measure collective efficacy to stop aggression. Participants were asked, “How well can the students and teachers at your school…” followed by the 10 items (e.g., “…work together to stop bullying”, “…work together to stop students punching each other?”, “…work together to stop students spreading rumors about each other?”). They rated each item on a seven-point scale (1 = “not well”, 2 = “just a little”, 3 = “a little”, 4 = “somewhat”, 5 = “moderately”, 6 = “quite a lot”, 7 = “very well”). The 10 items were averaged into one scale. A one factor model indicated good fit (\(\chi^{2}_{\text{Robust}} (35)\) = 892.096, p < .001, RMSEARobust = .064 (90% C.I.: .060; .067), CFIRobust = .990, SRMRRobust = .056, Cronbach’s α = .93). Collective efficacy for the classroom group was then computed as the classroom average.

Defending and reinforcing in bullying A 9-item scale was designed to measure defending and reinforcing in bullying situations. With reference to research showing that students might have varying understandings of the word “bullying” (Frisén et al. 2008; Guerin and Hennessy 2002; Purcell 2012), and that the word itself is considered to be negatively value-loaded (Felix et al. 2011) and associated with a risk of under-reporting, our defending–reinforcing scale did not provide the word bullying with an a priori definition. Instead, the definition was built into the questions. The participants were first asked, “If a student repeatedly gets punched, kicked, violently shoved or is held with force by students who are stronger, more popular, or more in charge in comparison to that student, what do you usually do?” representing physical bullying, and followed by a set of items. Next, the participants were asked, “If a student is repeatedly teased or called names by students who are stronger, more popular, or more in charge in comparison to that student, what do you usually do?” representing verbal bullying, and followed by a set of items.

The scale covered two subscales. The 5-item defender scale included two items in response to physical bullying and three items in response to verbal bullying (“I tell them to stop messing with the student” and “I step between and try to make them stop” in both forms of bullying, and “I tell a teacher” in verbal bullying; Cronbach’s α = .87). The 4-item reinforcer scale included two items in response to physical bullying and two items in response to verbal bullying (“I laugh and cheer at those who mess with the student” and “I think it’s fun so I stand and watch and laugh”; Cronbach’s α = .75). A two factor model indicated good fit (\(\chi^{2}_{\text{Robust}} (26)\) = 197.857, p < .001, RMSEARobust = .051 (90% C.I.: .044;.058), CFIRobust = .984, SRMRRobust = .058).

2.4 Statistical models

Separate multilevel regression models were analyzed for the dependent variables defending and reinforcing. First, a model with only the control variables gender and age was estimated for each dependent variable, allowing the intercept to vary between classrooms: Model 1 is shown below:

where DVij is the defending and reinforcing score, respectively, for the i:th student in the j:th classroom, \(\alpha_{j}\) is the intercept in classroom j, \(\beta_{1}\) to \(\beta_{2}\) are regression slopes for individual effects, εij is a student residual, α is the mean intercept across classes, and uj is a classroom residual. It is assumed that \(u_{j} \sim N\left( {0,\sigma_{u}^{2} } \right)\), \(\varepsilon_{ij} \sim N\left( {0,\sigma_{\varepsilon }^{2} } \right)\) and \(\text{cov} (u_{j} ,\varepsilon_{ij} ) = 0\), where σ2u is the variance between classrooms, and σ2ɛ is the variance within classrooms.

In the second model, the individual variables Moral Disengagement (MD) and Defender Self-Efficacy (DSE) were added. Model 2 is shown below:

where β1 to β4 are regression slopes for individual effects. The assumptions for model 2 are the same as for model 1.

In the third model, we added the classroom variable Collective Efficacy (CE). To explore the possibility that the relationships between MD and the dependent variable, and DSE and the dependent variable, were different in different classrooms, we added equations for the slopes of MD and DSE. Model 3 is shown below:

where β3j and β4j are the regression slopes for MD and DSE respectively in classroom j, β3 and β4 are mean regression coefficients across classrooms, to γ3 are regression slopes for classroom effects, and u1j to u2j are classroom residuals. It is assumed that the classroom residuals have a multivariate normal distribution with mean vector 0 and covariance matrix Ψ.

If we substitute the bottom two equations for β3j and β4j into the top equation, we can see that the effects of CE on the relationships between the dependent variable and the individual variables (MD and DSE) will be estimated by two interaction terms.

3 Results

3.1 Descriptive statistics and correlations

Table 1 presents results from descriptive statistics and gender differences. As shown, boys scored significantly higher than girls in reinforcing and moral disengagement but neither defending nor defender self-efficacy were found to differ significantly between boys and girls. Pairwise correlations are presented in Table 2. As all correlations were calculated at individual level, collective efficacy here represents the individuals’ perceived collective efficacy to stop aggression. Age was negatively correlated with defender self-efficacy, collective efficacy and defending, and positively but very weakly correlated with reinforcing. Moral disengagement was positively correlated with collective efficacy and reinforcing. Defender self-efficacy was positively correlated with collective efficacy and defending and negatively correlated with reinforcing. Finally, collective efficacy was positively correlated with defending and negatively correlated with reinforcing. The correlations between the individual variables were not as high as to indicate a problem with multicollinearity (highest r = − .472).

3.2 Multilevel analyses

Table 3 displays estimates and standard errors from analyses in R, using the lme4 package, for models 1, 2 and 3, with dependent variables defending and reinforcing, respectively. All variables, except gender, were grand mean centered. Effect sizes in Table 3 are standardized (for all quantitative variables) or partially standardized (for gender) regression coefficients (see Lorah, 2018). They can thus be interpreted as the expected change in the number of standard deviations in the dependent variable, followed by a one standard deviation change (or difference in gender) in the independent variable.

3.2.1 Defending

As shown by the intraclass correlation (ICC), 9.1% of the variation in defending scores was between classrooms. The variance between classrooms was significant (p < .001 from a likelihood ratio test). As shown in Table 3, older students scored lower on defending, on average, however this relationship did not persist as more variables entered the regression equations. Students who scored higher on defender self-efficacy also tended to score higher on defending. The variance of the moral disengagement slope (p = .560) and the defender self-efficacy slope (p = .999) were not significant, and model 3 was thus reduced to a variance component model by omitting the terms u1j and u2j. As shown, students belonging to classrooms with higher levels of collective efficacy tended to score higher on defending, on average. There were no significant interaction effects between class- and individual level variables for defending.

3.2.2 Reinforcing

As presented in Table 3, only 2.3% of the total variation in reinforcing scores was between classrooms. In addition, the variance between classrooms was not significant according to a likelihood ratio test (p = .055), and we therefore decided to reduce the models (1 to 3) to regression models. Girls scored lower on reinforcing, however this effect was no longer significant as more variables were added (in model 3). Students who scored higher on moral disengagement and lower on defender self-efficacy tended to score higher on reinforcing. In addition, students in classrooms with higher levels of collective efficacy scored lower, on average, on reinforcing. The positive relationship between moral disengagement and reinforcing was less strong in these classrooms (see Fig. 1), as was the negative relationship between defender self-efficacy and reinforcing (see Fig. 2).

4 Discussion

The current study investigated to what extent defending and reinforcing in school bullying were related to moral disengagement in bullying situations, defender self-efficacy, and collective efficacy to stop peer aggression while controlling for gender and age in late childhood. Although boys were more inclined to act as reinforcers than girls, and defending declined with age, these associations were no longer significant when included together with the social-cognitive correlates in the multilevel regression models.

4.1 Moral disengagement

In accordance with our hypothesis and the very few previous studies (Gini 2006; Sjögren et al. 2020; Thornberg and Jungert 2013), it was found that moral disengagement was positively associated with reinforcing, suggesting that students with a stronger tendency to morally disengage in bullying situations are more inclined to laugh and cheer on the bullies when witnessing school bullying. In other words, moral disengagement is not only linked to greater bullying perpetration (Gini et al. 2014) but also to a bystander behavior that previous studies have shown to be associated with a higher bullying prevalence among classmates (Kärnä et al. 2010; Nocentini et al. 2013; Salmivalli et al. 2011; Thornberg and Wänström 2018).

Contrary to our hypothesis and previous studies (e.g., Gini 2006; Gini et al. 2018b; Pozzoli et al. 2016; Thornberg et al. 2015; Thornberg et al., 2017), but in line with Barchia and Bussey’s (2011b) and Sjögren and colleagues' studies, moral disengagement was not significantly associated with defending in the current study. This relationship tends to be significant but weak in other studies (e.g., Gini et al. 2018b; Mazzone et al. 2016; Thornberg et al. 2017), particularly in comparison to how moral disengagement is related to bullying (Gini 2006; Thornberg et al. 2015) and reinforcing (Gini 2006; Sjögren et al. 2020; Thornberg and Jungert 2013). In Killer and colleagues' (2019) meta-analysis, the negative link between moral disengagement and defending was in fact weaker than the positive link between moral disengagement and bullying. A possible explanation to our findings might therefore be that the negative association between moral disengagement and defending varies in weakness across samples in a way that could include an insignificant relationship in some samples, such as in the current study and in Barchia and Bussey’s (2011b) and Sjögren and colleagues' studies. In sum, moral disengagement seems to be a more important construct in explaining inhibitive moral agency (the ability to refrain from behaving inhumanely; Bandura 2016) such as aggression, bullying and reinforcing, than proactive moral agency (the ability to help others in need and efforts to further their well-being, often at personal costs; Bandura 2016) such as defending a victim in bullying, at least among students in bullying and peer aggression situations.

4.2 Defender self-efficacy

The findings of the present study further demonstrated that defender self-efficacy was associated with greater defending, which supports our hypothesis and previous research (e.g., Barchia and Bussey 2011b; Doramajian and Bukowski 2015; Peets et al. 2015; Pöyhönen et al. 2012; Thornberg et al. 2017; van der Ploeg et al. 2017). Thus, our study suggests that the capacity to enact moral agency among students when they are witnessing school bullying is dependent on their beliefs in their individual capacities to successfully intervene and help the victim, which, in turn, supports the social-cognitive theory of moral agency (Bandura 2016). In accordance with our hypothesis and a few previous studies (Pöyhönen et al. 2012; Sjögren et al. 2020; Thornberg and Jungert 2013), defender self-efficacy was found to be linked to greater reinforcing, even though the link was weak. Thus, low defender self-efficacy does not only inhibit defending and increases the risk that students remain passive as bystanders (e.g., Thornberg and Jungert 2013; Thornberg et al. 2017) but also that they laugh and cheer on the bullies. Regardless, whereas moral disengagement seems to be more important in explaining reinforcing (inhibitive moral agency when witnessing school bullying), defender self-efficacy appears to be more important in explaining defending (proactive moral agency when witnessing school bullying).

4.3 Collective efficacy to stop peer aggression

Even though between-classroom variability in bullying can be partly explained by the prevalence of reinforcing and defending bystander responses (e.g., Kärne et al. 2010; Nocentini et al. 2013), relatively little is known about how contextual factors in the peer group at the classroom level are associated with such bystander behaviors. To our knowledge, the current study was the first to examine how collective efficacy to stop peer aggression as a group characteristic at the classroom level might be related to defending and reinforcing in school bullying. Barchia and Bussey’s (2011b) study was the first one to examine whether individually perceived collective efficacy to stop peer aggression was associated with defending. Their findings indicated that adolescents with a stronger individual belief in the ability of students and teachers to work together to stop peer aggression in schools, were in fact more inclined to defend victims in peer aggression situations. Our results add to their findings by suggesting that students who belonged to a classroom peer group with a stronger shared belief to stop peer aggression in schools were more inclined to defend victims in school bullying situations. In addition, our findings revealed that a higher degree of collective efficacy to stop aggression at the classroom level was also related to less reinforcing in school bullying. Thus, the current study suggests that collective efficacy to stop aggression is a contextual protective factor at the classroom level that facilitates classmates to defend victims at the same time as it inhibits them to reinforce bullying as bystanders.

4.4 Interplay between collective efficacy and individual social-cognitive factors

In line with the assumption of codetermination within the social-cognitive theory (Bandura 1997, 2016), we found cross-level interaction effects that shed some light on the interplay between classroom collective and individual social-cognitive correlates on reinforcing. Students who scored high in moral disengagement as well as students with low defender self-efficacy were more likely to reinforce bullying as bystanders if they belonged to a classroom with low collective efficacy to stop peer aggression. Thus, a weak shared belief in the peer group at the classroom level to stop peer aggression in schools seems to function as a risk factor that amplifies the individual risk factor of high moral disengagement in making students more inclined to reinforce school bullying as bystanders, at the same time as it made those with a low defender self-efficacy more inclined to reinforce bullying as well. Taken together, our findings support Bandura’s (1997, 2016) social-cognitive theory which states that actions are the products of the interplay of personal and social influences.

4.5 Limitations

Some limitations of the study should be noted. First, we adopted a cross-sectional design, and are therefore unable to draw causal conclusions and pinpoint the direction of effects. The social-cognitive theory not only assumes that cognitions predict behaviors, but also that behaviors predict cognition, and thus, suggests bidirectional effects between cognitions and behaviors as it proposes a codetermination or interplay between environmental, individual, and behavioral influences (Bandura 1997, 2016). Future research should examine the associations between moral disengagement, defender self-efficacy, collective efficacy, defending and reinforcing longitudinally. Second, the self-reported data in the current study might inflate variable associations at the individual levels due to shared methods variance. Self-reporting is also vulnerable to social desirability, careless marketing, and intentionally exaggerated responses. Finally, because we studied students within a particular age span and from particular areas in Sweden, our sample may or may not be similar to the population of students with whom readers primarily work or have an interest in.

4.6 Practical implications

As school bullying is linked to less defending and greater reinforcing among classmates (e.g., Kärnä et al. 2010; Nocentini et al. 2013), bullying prevention should include efforts to target these bystander behaviors. The current findings suggest the importance of developing interventions to (a) counteract and reduce moral disengagement in order to decrease reinforcing, and (b) increase students’ beliefs in their capacity to defend victims in order to increase defending. According to the social-cognitive theory (Bandura 1997; Fernández-Ballesteros et al. 2002), human agency cannot be reduced to individual characteristics independent of contextual factors. People are interdependent, and there is an interplay between contextual and individual factors. Collective agency means that people pool their competences and resources, and work together to achieve things. As Pöyhönen et al. (2012) stated, “It may therefore not be the most effective practice to aim to change cognitions and values of individual students, but to address the whole group (school or class) simultaneously” (p. 738). Our findings support this approach and suggest that bullying prevention should include efforts at the classroom level to develop and strengthen the student groups’ shared beliefs in the ability of students and teachers to work together to stop peer aggression in schools in order to promote and increase defending and inhibit and decrease reinforcing.

References

Abbate, C., & Ruggieri, S. (2016). The effect of social norms and the presence of bystanders on altruistic behavior. In T. Steele (Ed.), Prosocial behavior: Perspectives, influences and current research (pp. 33–71). Hauppauge, NY: Nova Science.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York, NY: Freeman and Company.

Bandura, A. (1999). Moral disengagement in the perpetration of inhumanities. Personality and Social Psychology Review,3, 193–209. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr0303_3.

Bandura, A. (2002). Selective moral disengagement in the exercise of moral agency. Journal of Moral Education,31, 101–119.

Bandura, A. (2016). Moral disengagement: How people do harm and live with themselves. New York: Worth.

Barchia, K., & Bussey, K. (2011a). Individual and collective social cognitive influences on peer aggression: Exploring the contribution of aggression efficacy, moral disengagement, and collective efficacy. Aggressive Behavior,37, 107–120.

Barchia, K., & Bussey, K. (2011b). Predictors of student defenders of peer aggression victims: Empathy and social cognitive factors. International Journal of Behavioral Development,35, 289–297. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025410396746.

Chen, L.-M., Chang, L. Y. C., & Cheng, Y.-Y. (2016). Choosing to be a defender or an outsider in a school bullying incident: Determining factors and the defending process. School Psychology International,37, 298–302. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034316632282.

Craig, W. M., Pepler, D., & Atlas, R. (2000). Observations of bullying in the playground and in the classroom. School Psychology International,21, 22–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034300211002.

Doramajian, C., & Bukowski, W. M. (2015). A longitudinal study of the associations between moral disengagement and active defending versus passive bystanding during bullying situations. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly,61, 144–172. https://doi.org/10.13110/merrpalmquar1982.61.1.0144.

Felix, E. D., Sharkey, J. D., Green, J. G., Furlong, M. J., & Tanigawa, D. (2011). Getting precise and pragmatic about the assessment of bullying: The development of the California bullying victimization scale. Aggressive Behavior, 37(3), 234–247.

Fernández-Ballesteros, R., Díez-Nicolás, J., Carpara, G. V., Barbaranelli, C., & Bandura, A. (2002). Determinants and structural relation of personal efficacy to collective efficacy. Applied Psychology,51, 107–125. https://doi.org/10.1111/1464-0597.00081.

Fischer, P., Krueger, J. I., Greitemeyer, T., Vogrincic, C., Kastenmüller, A., Frey, D., et al. (2011). The bystander-effect: A meta-analytic review on bystander intervention in dangerous and non-dangerous emergencies. Psychological Bulletin,137, 517–537.

Fisher, B. W., Gardella, J. H., & Teurbe-Tolon, A. R. (2016). Peer cybervictimization among adolescents and the associated internalizing and externalizing problems: A meta-analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence,45, 172–1743.

Forsberg, C., Thornberg, R., & Samuelsson, M. (2014). Bystanders to bullying: Fourth- to seventh-grade students’ perspectives on their reactions. Research Papers in Education,29, 557–576.

Forsberg, C., Wood, L., Smith, J., Varjas, K., Meyers, J., Jungert, T., et al. (2018). Students’ views of factors affecting their bystander behaviors in response to school bullying: A cross-collaborative conceptual qualitative analysis. Research Papers in Education,33, 127–142. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2016.1271001.

Fry, D., Fang, X., Elliott, S., Casey, T., Zheng, X., Li, J., et al. (2018). The relationships between violence in childhood and educational outcomes: A global systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Abuse and Neglect,75, 6–28.

Garcia, S. M., Weaver, K., Darley, J. M., & Spence, B. T. (2009). Dual effects of implicit bystanders: Inhibiting vs. facilitating helping behavior. Journal of Consumer Psychology,19, 215–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2009.02.013.

Gini, G. (2006). Social cognition and moral cognition in bullying: What’s wrong? Aggressive Behavior,32, 528–539. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.20153.

Gini, G., Card, N. A., & Pozzoli, T. (2018a). A meta-analysis of the differential relations of traditional and cyber-victimization with internalizing problems. Aggressive Behavior,44, 185–198.

Gini, G., Pozzoli, T., & Bussey, K. (2015). The role of individual and collective moral disengagement in peer aggression and bystanding: A multilevel analysis. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology,43, 441–452. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-014-9920-7.

Gini, G., Pozzoli, T., & Hymel, S. (2014). Moral disengagement among children and youth: A meta-analytic review of links to aggressive behavior. Aggressive Behavior,40, 56–68.

Gini, G., Thornberg, T., & Pozzoli, T. (2018b). Individual moral disengagement and bystander behavior in bullying: The role of moral distress and collective moral disengagement. Psychology of Violence. https://doi.org/10.1037/vio0000223.

Guerin, S., & Hennessy, E. (2002). Pupils’ definitions of bullying. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 17(3), 249–261.

Hymel, S., McClure, R., Miller, M., Shumka, E., & Trach, J. (2015). Addressing school bullying: Insights from theories of group processes. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 37, 16–24.

Jimerson, S. R., Swearer, S. M., & Espelage, D. L. (Eds.). (2010). Handbook of bullying in schools: An international perspective. New York, NY: Routledge.

Kärnä, A., Voeten, M., Poskiparta, E., & Salmivalli, C. (2010). Vulnerable children in different classrooms: Classroom-level factors moderate the effect of individual risk on victimization. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly,56, 261–282. https://doi.org/10.1353/mpq.0.0052.

Killer, B., Bussey, K., Hawes, D. J., & Hunt, C. (2019). A meta-analysis of the relationship between moral disengagement and bullying roles in youth. Aggressive Behavior, 45(4), 450–462.

Lorah, J. (2018). Effect size measures for multilevel models: definition, interpretation, and TIMSS example. Large-scale Assessments in Education,6, 8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40536-018-0061-2.

Mazzone, A., Camodeca, M., & Salmivalli, C. (2016). Interactive effects of guilt and moral disengagement on bullying, defending and outsider behavior. Journal of Moral Education,45, 419–432. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057240.2016.1216399.

Nakamoto, J., & Schwartz, D. (2010). Is peer victimization associated with academic achievement? A meta-analytic review. Social Development,19, 221–242.

Nocentini, A., Menesini, E., & Salmivalli, C. (2013). Level and change of bullying behavior during high school: A multilevel growth curve analysis. Journal of Adolescence,36, 495–505. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.02.004.

Obermann, M.-L. (2011). Moral disengagement among bystanders to school bullying. Journal of School Violence,10, 239–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2011.578276.

O’Connell, P., Pepler, D., & Craig, W. (1999). Peer involvement in bullying: Insights and challenges for observation. Journal of Adolescence,22, 437–452. https://doi.org/10.1006/jado.1999.0238.

Peets, K., Pöyhönen, V., Juvonen, J., & Salmivalli, C. (2015). Classroom norms of bullying alter the degree to which children defend in response to their affective empathy and power. Developmental Psychology,51, 913–920.

Polanin, J. R., Espelage, D. L., & Pigott, T. D. (2012). A meta-analysis of school-based bullying prevention programs' effects on bystander intervention behavior. School Psychology Review, 41, 47–65.

Pöyhönen, V., Juvonen, J., & Salmivalli, C. (2010). What does it take to stand up for the victim of bullying? Merrill-Palmer Quarterly,56, 143–163. https://doi.org/10.1353/mpq.0.0046.

Pöyhönen, V., Juvonen, J., & Salmivalli, C. (2012). Standing up for the victim, siding with the bully or standing by? Bystander responses in bullying situations. Social Development,21, 722–741. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.2012.00662.x.

Pozzoli, T., & Gini, T. (2012). Why do bystanders of bullying help or not? A multidimensional model. Journal of Early Adolescence,33, 315–340. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431612440172.

Pozzoli, T., Gini, G., & Thornberg, R. (2016). Bullying and defending behavior: The role of explicit and implicit moral cognition. Journal of School Psychology,59, 67–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2016.09.005.

Purcell, A. (2012). A qualitative study of perceptions of bullying in Irish primary schools. Educational Psychology in Practice, 28(3), 273–285.

Rigby, K., & Johnson, B. (2006). Expressed readiness of Australian schoolchildren to act as bystanders in support of children who are being bullied. Educational Psychology,26, 425–440. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410500342047.

Salmivalli, C. (2010). Bullying and the peer group: A review. Aggression and Violent Behavior,15, 112–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2009.08.007.

Salmivalli, C., Lagerspetz, K., Björkqvist, K., Österman, K., & Kaukiainen, A. (1996). Bullying as a group process: Participant roles and their relations to social status within the group. Aggressive Behavior,22, 1–15.

Salmivalli, C., & Voeten, M. (2004). Connection between attitudes, group norms, and behaviour in bullying situations. International Journal of Behavioral Development,28, 246–258. https://doi.org/10.1080/01650250344000488.

Salmivalli, C., Voeten, M., & Poskiparta, E. (2011). Bystanders matter: Associations between reinforcing, defending, and the frequency of bullying in classrooms. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology,40, 668–676. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2011.597090.

Sjögren, B., Thornberg, R., Wänström, L. & Gini, G. (2020). Bystander behaviour in peer victimisation: Moral disengagement, defender self-efficacy and student-teacher relationship quality. Research Papers in Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2020.1723679

Thornberg, R., & Jungert, T. (2013). Bystander behavior in bullying situations: Basic moral sensitivity, moral disengagement and defender self-efficacy. Journal of Adolescence,36, 475–483. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.02.003.

Thornberg, R., & Jungert, T. (2014). School bullying and the mechanisms of moral disengagement. Aggressive Behavior,40, 99–108. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21509.

Thornberg, R., Landgren, L., & Wiman, E. (2018). ’It depends’: A qualitative study on how adolescent students explain bystander intervention and non-intervention in bullying situations. School Psychology International,39, 400–415.

Thornberg, R., Pozzoli, T., Gini, G., & Jungert, T. (2015). Unique and interactive effects of moral emotions and moral disengagement on bullying and defending among school children. Journal of Elementary School,116, 322–337. https://doi.org/10.1086/683985.

Thornberg, R., & Wänström, L. (2018). Bullying and its association with altruism toward victims, blaming the victims, and classroom prevalence of bystander behaviors: A multilevel analysis. Social Psychology of Education,21, 1133–1151. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-018-9457-7.

Thornberg, R., Wänström, L., Hong, J. S., & Espelage, D. L. (2017). Classroom relationship qualities and social-cognitive correlates of defending and passive bystanding in school bullying in Sweden: A multilevel study. Journal of School Psychology,63, 49–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2017.03.002.

Trach, J., Hymel, S., Waterhouse, T., & Neale, K. (2010). Bystander responses to school bullying: A cross-sectional investigation of grade and sex differences. Canadian Journal of School Psychology,25, 114–130. https://doi.org/10.1177/0829573509357553.

van der Ploeg, R., Kretschmer, T., Salmivalli, C., & Veenstra, R. (2017). Defending victims: What does it take to intervene in bullying and how is it rewarded by peers? Journal of School Psychology,65, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2017.06.002.

Wänström, L., Pozzoli, T., Gini, G., Thornberg, R., & Alsaadi, S. (2017). Perceived collective efficacy to stop aggression at school: A validation of an Italian and a Swedish version of a scale for adolescents. European Journal of Developmental Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2017.1414695.

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by Linköping University. This research was partially supported by a grant awarded to Robert Thornberg from The Swedish Research Council (Grant Number D0775301).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Thornberg, R., Wänström, L., Elmelid, R. et al. Standing up for the victim or supporting the bully? Bystander responses and their associations with moral disengagement, defender self-efficacy, and collective efficacy. Soc Psychol Educ 23, 563–581 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-020-09549-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-020-09549-z