Abstract

With reference to social-ecological, self-determination, attributional, and social cognitive theories, the current study examined whether gender, age, altruistic motivation to defend victims, and tendency to blame the victims, at the individual level, and the prevalence of reinforcing and defending, at the classroom level, were associated with bullying. A sample of 901 Swedish students (9–13 years old, M = 11.00, SD = .83) from 43 classrooms filled out a questionnaire. Multilevel regression analyses revealed that the perpetration of bullying was positively associated with the prevalence of reinforcing at the classroom level and blaming the victims at the individual level, whereas it was negatively associated with altruistic motivation to defend victims of bullying at the individual level. Furthermore, students with high altruistic motivation to defend victims of bullying were less inclined to bully, independent of the classroom level of reinforcing. The current study suggests that bullying prevention and intervention programs should: explicitly target bystander behaviors, in particular to reduce the prevalence of reinforcing bullying; include efforts to strengthen altruistic self-concept and motivation to defend victims; and prevent, challenge, and counteract tendencies among students to blame the victim.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Bullying generally means that “an individual or a group of individuals repeatedly attacks, humiliates, and/or excludes a relatively powerless person” (Salmivalli 2010, p. 112). It is a serious problem in schools (Espelage et al. 2016; Rigby 2017; Young-Jones et al. 2015), and victims of bullying are at higher risk of developing mental-health problems such as low self-esteem, depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation and behaviors (Farrington et al. 2012; Gini and Pozzoli 2013; Reijntjes et al. 2010). According to the social-ecological framework (Bronfenbrenner 1979; Espelage 2014; Espelage and Swearer 2011), bullying is established, sustained, and changed over time as a result of reciprocal associations between individual and contextual factors. The most proximal social influences on children’s behaviors are situated within the microsystem, which consists of individuals or groups of individuals with whom the child interacts in the immediate environment, such as homes or schools (Bronfenbrenner 1979; Espelage 2014). In the school context, the peer ecology of the classroom microsystem is a significant everyday source of social influence on children’s behaviors toward others in school. As stated by Gini (2008):

Even if a child empathizes with the victim and thinks that bullying is wrong, group-level variables (i.e., need for peer acceptance, weakening of control or inhibition of aggressive tendencies, diffusion of responsibility, etc.) may encourage him or her to join in bullying, to sustain the bully or, at least, to remain aside. (p. 336)

In the current study, we examined whether students’ altruistic motivation to defend victims and their tendency to blame the victim, at the individual level, and the prevalence of reinforcing bullying and of defending victims of bullying, at the classroom level, were associated with bullying perpetration.

1.1 Individual factors

1.1.1 Gender and age

Gender differences in aggression and bullying might be explained in terms of gender-specific socialization across various socialization agents, including parents, peers, teachers, other adults, and the media, in which girls are more encouraged to engage in nurturing and caring behaviors, whereas aggression is more socially acceptable for boys (Carlo 2014). According to the two-cultures theory (Underwood 2004), children in middle childhood tend to play and socialize within their peer groups in a gender-segregated way, manifested as distinctive boy and girl cultures. Compared to girls, boys engage in higher rates of rough-and-tumble play, direct aggression, and competitive activities. They are more concerned with who is tougher than whom, talk with each other more directly and forcefully, are more prone to focus on themselves and to ignore the concerns of others, and are more inclined to be assertive in peer conflicts (for a review, see Underwood 2004). In line with this gender-specific socialization, previous studies have found boys to be more inclined than girls to use direct aggression (for a meta-analysis, see Card et al. 2008) and to bully others (for meta-analyses, see Cook et al. 2010; Mitsopoulou and Giovazolias 2015). Therefore, we hypothesized that boys would engage more in bullying perpetration than girls.

Developmental changes in preadolescence and early adolescence include more anxiety about friendships, conformity to peer pressure, and concerns about peer-group status, which in turn can lead to increased bullying and more negative attitudes toward victims (Smith 2010). Several studies have examined the relationship between age and bullying. Whereas Cook et al. (2010) meta-analysis revealed a weak but significant positive association between age and bullying, Kljakovic and Hunt’s (2016) meta-analysis showed a weak but significant negative association. Cook et al. (2010) included studies with participants in K-12 settings (5–18 years old), whereas Kljakovic and Hunt (2016) only included studies with a longitudinal or prospective design and with participants aged between 11 and 18 years. In line with this, a recent longitudinal Dutch study with data from 2230 participants revealed an overall decrease in bullying perpetration between pre- and late adolescence (Kretschmer et al. 2017). The current study was conducted in Sweden, and according to a national report from the Swedish National Agency for Education (2016), 9% of students in grades 4–6 (preadolescents), 3% of students in grades 7–9 (adolescents), and 2% of students in upper secondary school (late adolescents) reported that they felt bullied at school, which indicates that bullying seems to be more prevalent among preadolescents than adolescents in Sweden. This, in turn, supports Kljakovic and Hunt’s (2016) meta-analysis and the Dutch longitudinal study. However, due to the mixed findings and the small effect sizes reported in the two meta-analyses, and the rather limited age range in the current study (grades 4–6), age was included as a control variable in the present study but without a clear hypothesis.

1.1.2 Altruism toward victims

Altruism can be seen as “a form of unconditional kindness without the expectation of a return” (Hung et al. 2011, p. 418). Batson et al. (2004) define altruism as “a motivational state with the ultimate goal of increasing another person’s welfare” (p. 360; altruism and altruistic motivation are thus used interchangeably, see e.g., Batson and Ahmad 2009, pp. 5–6), and is contrasted with egoism. The latter can be defined as “a motivational state with the ultimate goal of increasing one’s own welfare” (Batson et al. 2004, p. 360). In accordance with Batson et al. (2004), we use the term altruism to refer to motivation, as opposed to behavior, and we assume that altruistic motivation is based on altruistic values. Prosocial or helping behavior can be driven by altruistic motivation, egoistic motivation, a mixture of both, or by other motives. Nevertheless, in contrast to egoistic motives, such as gaining social rewards and self-rewards or avoiding social sanctions or self-sanctions (i.e., extrinsic motivation), altruism can be understood as intrinsic motivation (Hung et al. 2011) or autonomous motivation (Gagné 2003; Gagné and Deci 2005). Within a self-determination theoretical framework (Deci and Ryan 2000), autonomous motivation can be further subdivided into three components: “intrinsic motivation (e.g., when helping in itself gives joy), integrated regulation (e.g., when being a volunteer is central to one’s identity), and identified regulation (e.g., when volunteering is considered to support an important personal cause)” (Haivas et al. 2012, p. 1197).

According to self-determination theory (Deci and Ryan 2000; Ryan and Connell 1989), autonomously motivated behaviors make people feel that they are the “origin” of the behavior rather than a “pawn” acting out the behavior, whereas controlled motivation is experienced as emanating either from external contingencies and controls or from self-imposed pressures, such as feelings of shame, guilt, or pride. According to self-determination theory, egoistic motivation to help someone in need is thus based on gaining rewards, advantages or benefits (e.g., making friends, receiving social approval or acceptance, and enhancing popularity) or avoiding punishments, sanctions or disadvantages (e.g., losing friends, being victimized, losing face, experiencing social disapproval/sanctions, and loss of benefits), and thus in line with the concept of controlled motivation (e.g., Gagné and Deci 2005; Haivas et al. 2012). Previous research has shown that autonomous motivation predicts stronger persistence than controlled motivation in several domains, such as academic performance (Niemiec and Ryan 2009; Taylor et al. 2014), health behavior changes and maintenance (Ng et al. 2012; Ryan et al. 2008), and job performance (Moran et al. 2012). Autonomous motivation has also been found to be associated with prosocial behavior (Hardy et al. 2015), and defender behavior in school bullying (Jungert et al. 2016).

In addition, altruism has been associated with greater prosocial behavior (for a review, see Bierhoff 2002) as well as defender behavior in both bullying (Lodge and Frydenberg 2005; Tani et al. 2003) and homophobic harassment situations (Poteat and Vecho 2016). Furthermore, and of interest for the current study, altruism has been associated with less aggression among adults (for a meta-analysis, see Jones et al. 2011). Although altruistic motivation to defend victims can be considered a vital component of moral agency (helping and defending the victim) in bullying situations, it is still unclear whether it is associated with less bullying behavior among children. However, with reference to its negative association with aggression among adults, we hypothesized that altruism would be negatively associated with bullying among children.

1.1.3 Blaming the victim

In her review, Moriarty (2008) concludes that there is a historical tendency to place responsibility for victimization on the victim, at least to some degree. There are widespread assumptions about “born victims” and shared responsibility between victims and offenders as well as a widespread tendency to blame the victims in our society. They are often considered to be deficient in some way, and therefore can be distinguished from non-victims based on their attitudes, behavior, or characteristics, which, in turn, are assumed to be the cause of their victimization. “If they were not different, they would not be victimized. Victims are then warned that they must change in order to become like the non-victim group if they are to avoid victimization, and if they fail to avoid victimization they are to blame” (Moriarty 2008, p. 31). The process of creating “culturally legitimate victims” is devastating to victims, who are further traumatized when society then engages in victim blaming (Moriarty 2008). Several studies have in fact found that a common explanation among children and adolescents for why bullying occurs is that the victim is different, odd, or deviant in some way (for a review, see Thornberg 2011). Moriarty (2008) argues that the concept of victim precipitation, in other words, the social perception that victims precipitate their own victimization, “provides a cultural framework which offenders can use to rationalize their behavior” (p. 32).

According to Lerner’s (1980) just world hypothesis, people tend to assume that victims have earned their suffering by their actions or characteristics. Blaming the victim is a way of maintaining a belief in having agency to avoid bad things by doing good things. According to Weiner’s (1995) attributional theory, blaming the victim functions as a self-serving attribution that allows perpetrators and bystanders to distance themselves from the victims and their sufferings. With reference to attributional theory tradition, the defensive attribution hypothesis (Burger 1981) states that, when observers blame the victim, they maintain the perception that the reasons for the victim’s situation are dispositional and not caused by an unpredictable set of circumstances beyond anyone’s control. By making sure that they are different from the victim, they can therefore avoid the victim’s suffering. Within Bandura’s (1999, 2016) social cognitive theory of moral disengagement, blaming the victim is considered to be a social-cognitive mechanism that distorts moral cognition, allowing the perpetrators to self-exonerate their inhumane behavior and, thus, allowing them to avoid feeling guilt or remorse.

According to previous research, bullying behavior has been associated with blaming the victim (Garland et al. 2017; Hara 2002; Thornberg 2015b; Thornberg and Jungert 2014; Thornberg and Knutsen 2011). An exception is one study in which the link was only found among 12-year-old boys, and not among 12-year-old girls or 9-year-old children (Gini 2008). Previous studies have shown boys to be more inclined to blame the victim than girls (Gini 2008; Hara 2002; Thornberg and Jungert 2014), which might help to explain the findings that boys more often bully others. In the current study, we hypothesized that blaming the victim would be positively associated with bullying.

1.2 Contextual factors

1.2.1 Classroom prevalence of reinforcing and defending

During the last few decades, researchers have increasingly theorized and empirically examined bullying as a social psychological phenomenon (for reviews, see Hymel et al. 2015; Saarento and Salmivalli 2015; Salmivalli 2010). Peer pressure has been found to be one of the most important predictors of bullying in the school context (for a meta-analysis, see Cook et al. 2010). Peer pressure can be understood as a pressure to feel, think, and behave in ways that are consistent with certain peer norms, and previous research has found that students are more inclined to display aggression when classroom peer norms favor aggression (Kuppens et al. 2008; Salmivalli and Voeten 2004). Furthermore, Saarento and Salmivalli (2015) argue that classroom norms can be reflected in explicit behaviors when students witness peer aggression or bullying. Their reactions provide direct feedback to the perpetrators in a way that can affect whether the aggression continues. Volke et al. (2014) define bullying as an “aggressive goal-directed behavior that harms another individual within the context of a power imbalance” (p. 328, italics in original), and they state that reputation (social dominance) is the most commonly cited benefit of bullying. Thus, bullying can be considered a function of the context (cf., Sundel and Sundel 2005) in which peers’ reactions can reinforce or inhibit (punish) bullying.

According to the participant role approach (Salmivalli 1999), there are, in addition to the bully role and the victim role, four possible bystander roles: assistants who join in and help the ringleader bullies, reinforcers who support and thus signal their approval of the bullying by laughing or cheering, outsiders who remain passive and try to stay away, and defenders who help and support the victim, and who therefore may display disapproval of the bullying or toward the bully depending on whether their intervention is more direct (e.g., telling the bully to stop bullying) or indirect (e.g., comforting the victim). In the current study, and in line with previous studies (e.g., Kärnä et al. 2010), we have focused on reinforcing and defending as classroom contextual factors.

Previous research has revealed that between-classroom variability in bullying can be explained in part by the prevalence of bystander behaviors. The more classmates reinforce bullying and fail to defend the victims, the more often bullying is likely to occur (Kärnä et al. 2010; Nocentini et al. 2013; Salmivalli et al. 2011). In their review, and with reference to previous studies, Saarento and Salmivalli (2015) conclude that bullies might be even more sensitive to reinforcing than defending. It is therefore reasonable to hypothesize that bullying is more prevalent in classrooms in which reinforcing is more common and defending is less common as bystander reactions, although the association between defending and bullying might be weaker than the association between reinforcing and bullying.

2 The current study

The aim of the current study was to examine whether gender, age, altruistic motivation to defend victims, and the tendency to blame the victim, at the individual level, and the prevalence of reinforcing and defending, at the classroom level, were associated with bullying. We hypothesized that being a boy, having a greater tendency to blame the victim and being exposed to a higher prevalence of reinforcing at the classroom level would all be associated with greater bullying. In contrast, we hypothesized that being a girl, having a greater altruistic motivation to defend victims and being exposed to a higher prevalence of defending at classroom level would be associated with less bullying. Age was included as a covariate. Because social-ecological theory emphasizes that bullying is produced by interdependent associations between individual and contextual factors, we also expected to find some cross-level effects. However, due to the lack of previous studies, the literature did not offer us any clear hypotheses to deduce and test. Therefore, possible cross-level interactions between the theoretical constructs were examined in an exploratory fashion.

3 Method

3.1 Participants

The study participants consisted of 901 students (48% girls) from 43 primary classrooms in 15 public schools located in two small villages in the countryside and in different neighborhoods of two midsize cities in Sweden (age range = 9–13 years old, M = 11.00, SD = .83). In Swedish primary schools, students have one classroom (homeroom) in which most of their lessons take place, and they have the same classroom teacher across most school subjects. Normally, they have one teacher in grades 1–3, who is then replaced by another classroom teacher in grades 4–6. Our study focused on students in grades 4–6. Socio-economic status was not directly measured in the study; however, the sample of public schools represented a wide range of socio-geographic locations and socio-economic statuses. Most participants were of Swedish ethnicity, and only a minority (16%) had an immigrant background; that is, either they were born in another country or at least one of their parents was born in another country. The original sample consisted of 996 students (48% girls), but 95 of those (10%) did not participate for various reasons: 74 students because they did not obtain parental consent, 19 because they were absent due to sickness during the data collection, and two because they did not want to. The participation rate was evenly spread over grades and gender.Footnote 1 We obtained written parental consent and oral student assent from all 901 participants.

3.2 Measures

3.2.1 Gender and age

Participants completed a question about their gender (0 = girl, 1 = boy), and a question about their age (i.e., “How old are you?” followed by, “I’m …… years and …… months old”).

3.2.2 Altruistic motivation

Three items from a developed self-rating scale on various motivations to defend victims of bullying (Thornberg 2015a) were used to measure altruistic motivation to defend bullying victims. The participants were asked: “What makes you want to help a bullied student?” The items used in the current study were: “Because I think it’s important to help people who are mistreated by others,” “Because I’m a person who cares about others,” and “Because I think it’s important to fight violence, oppression, and injustice.” Response options for each item were on a four-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = partly disagree, 3 = partly agree, 4 = strongly agree). The items were averaged for each participant (Cronbach’s α = .63).

3.2.3 Blaming the victim

Two items from the Short Moral Disengagement in Bullying scale (Thornberg and Jungert 2013) were used to measure the tendency to blame the victim in bullying situations. The included items were: “A person who is bullied only has him- or herself to blame” and “Some people deserve to be bullied.” Response options for each item were on a seven-point scale (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree). The items were averaged for each participant (Spearman-Brown coefficient = .59).

3.2.4 Bystander behavior

A 15-item bystander behavior scale (Thornberg et al. 2017) was used to measure bystander behavior in bullying situations. The scale covers all four possible participant bystander roles according to the participant role model (i.e., assistant, reinforcer, outsider, and defender; Salmivalli 1999), but in the current study we only included reinforcing and defending in the analyses. The participants were asked: “Try to remember situations in which you have seen a student being bullied (for example: teased, mocked, physically assaulted, or frozen out). What do you usually do?” Two items described reinforcing (“I laugh and cheer the bullies on,” “I encourage the bullies by shouting and laughing,” Spearman-Brown coefficient = .69); and five items described defending (e.g., “I tell them to stop fighting with the students,” “I tell a teacher,” “I comfort the bullied student,” Cronbach’s α = .80). Response options for each item were on a four-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = partly disagree, 3 = partly agree, 4 = strongly agree). Because we intended to measure participants’ self-reports of how they typically responded when they had witnessed bullying, the items were provided on an “agree–disagree” scale, as opposed to a “never–always” scale. The latter type of wording might increase the risk of confounding with the perceived frequency of witnessing bullying (cf., Thornberg and Jungert 2013). The items measuring reinforcing and defending were averaged for each participant, and the classroom averages were then calculated for each classroom.

3.2.5 Bullying perpetration

A five-item scale was developed in the current study to measure bullying perpetration. The participants were presented with a list of behavioral items and asked to rate: “How often has this happened at school in the past three months?” The items were, “I tease one or more students,” “I beat one or more students,” “I’m with others and freeze one or more students out,” “I spread mean rumors about one or more students” and “I threaten one or more students.” The participants indicated how often they had engaged in the behavior described in each item on a five-point scale (1 = “Never happened,” 2 = “A couple of times,” 3 = “2 or 3 times a month,” 4 = “About once a week” and 5 = “Several times a week”; Cronbach’s α = .92). Scores were averaged for each participant.

3.3 Procedure

Participants filled out the questionnaire in their ordinary classroom settings. Five student–teachers, at the end of their teacher training, were present in the classrooms during the data gathering (one student-teacher in each classroom). They explained the study procedure, reassured students that their participation was confidential, and assisted participants who needed help. The participants were also informed that they had the option of withdrawing from the study at any time. The participating students responded anonymously to the questionnaire.

3.4 Statistical models

We used multilevel regression models to analyze the dependent variable bullying (Bully) in order to account for the structure of students nested within classrooms. First, a model with the individual-level variables gender, age, altruism (AL) and blaming the victim (BTV) was estimated:

where bullyij is the bullying score for the ith student in the jth classroom, \(\alpha_{j}\) is the intercept in classroom j, \(\beta_{1}\) to \(\beta_{4}\) are regression slopes for individual effects, \(\varepsilon_{ij}\) is a student residual, \(\alpha\) is the mean intercept across classes, and \(u_{j}\) is a classroom residual. It is assumed that \(u_{j} \sim N\left({0,\sigma_{u}^{2}} \right)\), \(\varepsilon_{ij} \sim N\left({0,\sigma_{\varepsilon}^{2}} \right)\) and \(\text{cov} (u_{j} ,\varepsilon_{ij} ) = 0\), where \(\sigma_{u}^{2}\) is the variance between classrooms, and \(\sigma_{\varepsilon }^{2}\) is the variance within classrooms.

In the second model, the classroom-level variables reinforcing (RF) and defending (DF) were added:

where \(\beta_{1}\) to \(\beta_{4}\) are regression slopes for individual effects and \(\gamma_{1}\) to \(\gamma_{2}\) are regression slopes for classroom effects. The assumptions for model 2 are the same as for model 1.

In a third model, we explored the effects of classroom-level variables on the relationships between the individual-level variables altruism and blaming the victim and the dependent variable bullying by allowing the regression slopes for these variables to vary between classes:

where \(\beta_{3j}\) and \(\beta_{4j}\) are the regression slopes for altruism and blaming the victim in classroom j, \(\beta_{3}\) and \(\beta_{4}\) are mean regression coefficients across classrooms, \(\gamma_{1}\) to \(\gamma_{6}\) are regression slopes for classroom effects, and \(u_{0j}\) to \(u_{2j}\) are classroom residuals. It is assumed that the classroom residuals have a multivariate normal distribution with mean vector 0 and covariance matrix \(\varPsi\).

If we substitute the bottom two equations for \(\beta_{3j}\) and \(\beta_{4j}\) into the top equation, we can see that the effects of classroom variables (RF and DF) on the relationships between bullying and the individual variables (AL and BTV) will be estimated by four cross-level interaction terms.

4 Results

4.1 Descriptive statistics and correlations

Table 1 presents the results of the descriptive statistics for individual- and classroom-level variables. Pairwise correlations at the individual and classroom levels are presented in Tables 2 and 3. In Table 3, the class mean for the dependent variable bullying was used. As shown, altruism was negatively correlated with bullying, whereas blaming the victim was positively correlated with bullying. At the classroom level, bullying was negatively correlated with defending and positively correlated with reinforcing. In other words, classrooms with higher levels of reinforcing and lower levels of defending in bullying situations tended to have higher levels of bullying.

4.2 Multilevel analyses

Table 4 displays estimates and standard errors from analyses in SAS for models 1, 2 and 3. All variables, except gender, were grand mean centered. The intra-class correlation (ICC) was .03, indicating that 3% of the total variance in bullying was between classes. As shown (model 1), altruism was negatively associated with bullying, and blaming the victim was positively associated with bullying, controlling for gender and age. The class intercept variance was significant (although small), indicating that the classes vary in their mean bullying scores.

Altruism and blaming the victim were still associated with bullying when classroom-level variables were added (model 2). In addition, the classroom-level variable reinforcing was positively associated with bullying.

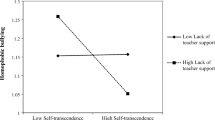

When cross-level interactions were added (model 3), the associations between the individual variables altruism and bullying as well as blaming the victim and bullying remained significant, as did the positive association between the classroom-level variables reinforcing and bullying. As shown, the interaction between the individual-level variable altruism and the classroom-level variable reinforcing was negative and significant, indicating that reinforcing had a negative effect (− 1.324) on the altruism slope (mean slope = − .095). This effect is illustrated in Fig. 1, for classes with low (1 standard deviation below the mean), medium, and high (1 standard deviation above the mean) reinforcing mean scores. As seen, the negative association between altruism and bullying was stronger for classes with high reinforcing mean scores, whereas it was close to flat for classes with low reinforcing means. In other words, students with high levels of altruism tended to score low on bullying independently of the prevalence of reinforcing at the classroom level, whereas students with low levels of altruism seemed to be more influenced by the prevalence of reinforcing. In addition (see Table 4), the association between blaming the victim and bullying (mean slope = .077) varied significantly between classes.

5 Discussion

5.1 Individual factors

Consistent with our hypotheses, and after controlling for gender and age, both altruism toward victims and the tendency to blame victims uniquely contributed to explaining the variance of bullying perpetration. Whereas previous findings have shown that altruism is linked with greater prosocial behavior (Bierhoff 2002), including defending in school bullying (Lodge and Frydenberg 2005; Tani et al. 2003), and less aggression among adults (Jones et al. 2011), the current findings contribute to the literature by demonstrating that altruistic motivation to defend victims was associated with less bullying perpetration among pre-adolescents. Thus, altruism seems to be a vital component of moral agency in bullying situations, not only in terms of promoting defending but also in inhibiting bullying perpetration. A high pattern of altruistic motivation might be associated with what Staub (2003) calls prosocial value orientation, which “consists of a positive view of human beings, caring about other people’s welfare, and a feeling of personal responsibility for others’ welfare” (p. 16), which is expected to be linked to habits of helping others as well as habits of not harming others.

In line with previous studies (Garland et al. 2017; Hara 2002; Thornberg 2015b; Thornberg and Jungert 2014; Thornberg and Knutsen 2011), as well as with attributional theory (Weiner 1995) and social cognitive theory of moral disengagement (Bandura 1999, 2016), blaming the victims was associated with greater bullying perpetration in the present study. With reference to attribution theory, Gini (2008) argues that “in the case of potentially harmful events, blaming other individuals is a very real self-serving attribution and, in particular, blaming the victims for their fate allows people to distance themselves from thoughts of suffering” (p. 337). As a social-cognitive mechanism that distorts moral cognition (Bandura 1999, 2016), blaming the victims helps those who bully to reduce or neutralize empathic concerns or distress (Hoffman 2000) and to prevent them from feeling guilt or remorse (Bandura 1999, 2016).

Gender was significantly associated with bullying in the bivariate correlation analysis, which means that boys bullied more than girls, as we expected (cf., Mitsopoulou and Giovazolias 2015). However, when included as a control variable in the multilevel analysis, gender was no longer significantly associated with bullying. In addition, we found no associations between age and bullying in the current study, which is partly in line with the small effect sizes and mixed findings of previous meta-analyses (Cook et al. 2010; Kljakovic and Hunt 2016), but might also be due to the fact that our sample only included students from grades 4–6 in Swedish schools.

5.2 Classroom contextual factors

Our findings support previous research showing that the between-classroom variability of bullying can be partly explained by the prevalence of reinforcing and defending (Kärnä et al. 2010; Nocentini et al. 2013; Salmivalli et al. 2011). In accordance with our hypotheses, the bivariate correlation analyses demonstrated that the more classmates reinforced bullying and the less they defended the victims in bullying incidents, the more often bullying was likely to occur. However, after controlling for gender, age, altruism toward victims and blaming the victims at the individual level, the only bystander behavior that contributed to explaining the variance of bullying perpetration was the prevalence of reinforcing. This could be in line with previous findings showing that the association between reinforcing and bullying is stronger than the association between defending and bullying (e.g., Salmivalli et al. 2011), and with Saarento and Salmivalli’s (2015) conclusion that bullies might be more sensitive to reinforcing than defending.

There might be several possible explanations as to why defending was not significantly associated with bullying in the multilevel analysis in the current study. In the Finnish and Italian studies (Kärnä et al. 2010; Nocentini et al. 2013; Salmivalli et al. 2011), the samples were larger (resulting in more statistical power) and the measurement of bystander behaviors was based on peer nominations, whereas the measurement of bystander behaviors in the current study was based on self-reports. Differences in bullying measurements and statistical modeling, as well as in the inclusion of other variables in the statistical models, might also help explain the differences between the results. Furthermore, in Kärnä and colleagues’ (2010) study, victimization was measured instead of bullying perpetration, and at the classroom level in the multilevel growth model in the Italian study (Nocentini et al. 2013), only pro-bullying (i.e., assistant and reinforcer) behavior was associated with the baseline level of bullying (intercept), whereas defending was associated with a decrease in bullying over time (slope). However, our findings, together with the Finnish and Italian studies, suggest that a high prevalence of reinforcing at the classroom level is a risk factor for bullying. As a bystander reaction to bullying, it provides direct feedback to the bullies, and encourages their bullying behavior, suggesting that bullying is a function of the peer context (cf., Sundel and Sundel 2005) and a goal-directed behavior (Volke et al. 2014) seeking to achieve social rewards.

5.3 Interplay between individual and contextual factors

The present study is the first to examine whether high levels of altruism toward victims might weaken the association between the classroom-level prevalence of reinforcing and bullying perpetration. In line with the social-ecological framework (Espelage 2014; Espelage and Swearer 2011), the current findings reveal a cross-level interaction effect that sheds some light on the interplay between individual- and classroom-level contextual factors in relation to bullying. Students with high altruistic motivation to defend victims in bullying were less inclined to bully, independently of the classroom level of reinforcing. In contrast to bullying or refraining from bullying others in order to gain social rewards and to avoid social sanctions, altruistic motivation might be understood as a more autonomous motivation in which refraining from bullying others is perceived to be a voluntary and self-determined action rather than controlled by peer pressure or other external contingencies. According to the self-determination theory (Deci and Ryan 2000; Ryan and Connell 1989), autonomous motivation predicts stronger persistence than external or controlled motivation across several domains (e.g., Tayler et al. 2015; Ryan et al. 2008; Moran et al. 2012). In contrast, those with low altruistic motivation to defend victims were more dependent on the classroom prevalence of reinforcing, and thus more inclined to bully if the classroom level of reinforcing was high.

5.4 Limitations

Despite the many strengths of this study, some limitations should be noted. First, the variables have been assessed through self-reporting, which might inflate variable associations due to shared methods variance at the individual level. Self-reporting is also vulnerable to careless marking, social desirability and intentionally exaggerated responses, which could inflate or diminish the estimates (Cornell and Bandyopadhyay 2010). Second, we adopted a cross-sectional design, and are therefore unable to pinpoint the direction of effects. For example, it is not clear whether blaming the victim is a predictor of bullying perpetration, or if bullying predicts the propensity to blame the victims. It is also possible that the relations found in the study are reciprocal. Future research needs to adopt a longitudinal design to examine this further. Third, there were only 43 classrooms. Non-significant findings at the classroom level (i.e., defending) should therefore be interpreted with caution. Fourth, two scales (blaming the victims and altruistic motivation) were only measured by two and three items, respectively, and therefore had fairly low internal reliabilities. Future studies might use more items to measure these constructs. Finally, because we studied students within a particular age span and from particular areas in Sweden, our sample may or may not be similar to the population of students with whom readers primarily work or have an interest in.

5.5 Implications

The above limitations aside, the present findings have some practical implications. In line with some other studies (Kärnä et al. 2010; Nocentini et al. 2013; Salmivalli et al. 2011), our study suggests that bullying prevention and intervention programs should explicitly target bystander behaviors, in particular in order to reduce the prevalence of reinforcing bullying. Whereas Polanin et al.'s (2012) meta-analysis of 11 studies on school-based interventions designed to change bystanders’ behaviors revealed an increase in bystanders’ defending in bullying situations as compared with control groups, further research is needed to examine how programs can reduce bystanders’ reinforcing, as such efforts would reduce or remove the social approval, rewards and encouragement of bullying. For instance, educational efforts aimed at increasing students’ acceptance of others, which implies a positive attitude toward others in general, might be considered as one means of influencing bystander behaviors, as it has been found to be associated with pro-victim attitudes (Rigby and Bortolozzo 2013). School factors such as school climate (Bibou-Nakou et al. 2012) and the general quality of relationships among students at the classroom level (Thornberg et al. 2017) might also be considered in order to influence the prevalence of bullying and various bystander behaviors.

Moreover, bullying prevention should include efforts to strengthen altruistic self-concept and motivation to defend victims among the students for at least two reasons. Our findings showed that high altruism toward victims was associated with less bullying perpetration and, in addition, weakened the positive association between the classroom level of reinforcing and bullying perpetration, and thus seemed to have made students more resistant to peer influence that encouraged and rewarded bullying. Thus, moral education aimed at enabling students to develop a moral identity with altruistic values and altruistic motivation to help others in distress (cf., Carlo 2014) should be part of the bullying prevention program. Finally, prevention and intervention programs should prevent, challenge, and counteract tendencies among students to blame the victim, in order to reduce bullying. For example, Moriarty (2008) points to some of the fallacies in victim blaming such as the use of tautological reasoning (or circular thinking), placing undue responsibility on victims, creating culturally legitimate victims, excusing offenders’ behaviors and diminishing responsibility, and bullying prevention programs could help students to be aware of these issues.

Notes

Results from a multilevel logistic regression analysis with participation/non-participation as the response variable and gender and grade as the predictors indicated no significant effects.

References

Bandura, A. (1999). Moral disengagement in the perpetration of inhumanities. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 3, 193–209.

Bandura, A. (2016). Moral disengagement: How people do harm and live with themselves. New York: Worth.

Batson, C. D., & Ahmad, N. Y. (2009). Empathy-induced altruism: A threat to the collective good. In S. R. Thye & E. J. Lawler (Eds.), Altruism and prosocial behavior in groups (Advanced in group processes (Vol. 26, pp. 1–23). Emerald Group: Bingley.

Batson, C. D., Ahmad, N. Y., & Stocks, E. L. (2004). Benefits and liabilities of empathy-induced altruism. In A. G. Miller (Ed.), The social psychology of good and evil (pp. 359–385). New York: Guilford Press.

Bibou-Nakou, I., Tsiantis, J., Assimopoulos, H., Chatzilambou, P., & Giannakopoulou, D. (2012). School factors related to bullying: A qualitative study of early adolescent students. Social Psychology of Education, 15, 125–145.

Bierhoff, H.-W. (2002). Prosocial behaviour. Hove: Psychology Press.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Burger, J. M. (1981). Motivational biases in the attribution of responsibility of the defensive-attribution hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 90, 496–512.

Card, N. A., Stucky, B. D., Sawalani, G. M., & Little, T. D. (2008). Direct and indirect aggression during childhood and adolescence: A meta-analytical review of gender differences, intercorrelations, and relations to maladjustment. Child Development, 79, 1185–1229.

Carlo, G. (2014). The development and correlates of prosocial moral behaviors. In M. Killen & J. G. Smetana (Eds.), Handbook of moral development (2nd ed., pp. 208–234). New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Cook, C. R., Williams, K. R., Guerra, N. G., Kim, T. E., & Sadek, S. (2010). Predictors of bullying and victimization in childhood and adolescence: A meta-analytic investigation. School Psychology Quarterly, 25, 65–83.

Cornell, D. G., & Bandyopadhyay, S. (2010). The assessment of bullying. In S. R. Jimerson, S. M. Swearer, & D. L. Espelage (Eds.), Handbook of bullying in schools: An international perspective (pp. 265–276). New York, NY: Routledge.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The ‘‘what’’ and ‘‘why’’ of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11, 227–268.

Espelage, D. L. (2014). Ecological theory: Preventing youth bullying, aggression, and victimization. Theory into Practice, 53, 257–264. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.4014.947216.

Espelage, D. L., Hong, J. S., & Mebane, S. (2016). Recollections of childhood bullying and multiple forms of victimization: Correlates with psychological functioning among college students. Social Psychology of Education, 19, 715–728.

Espelage, D. L., & Swearer, S. M. (Eds.). (2011). Bullying in North American schools (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

Farrington, D. P., Lösel, F., Ttofi, M. M., & Theodorakis, N. (2012). School bullying, depression and offending behaviour later in life. Stockholm: National Council for Crime Prevention.

Gagné, M. (2003). The role of autonomy support and autonomy orientation in prosocial behavior engagement. Motivation and Emotion, 27, 199–223.

Gagné, M., & Deci, E. L. (2005). Self-determination theory and work motivation. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26, 331–363.

Garland, T. S., Policastro, C., Richards, T. N., & Miller, K. S. (2017). Blaming the victim: University student attitudes toward bullying. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 26, 69–87.

Gini, G. (2008). Italian elementary and middle school students’ blaming the victim of bullying and perception of school moral atmosphere. The Elementary School Journal, 108, 335–354.

Gini, G., & Pozzoli, T. (2013). Bullied children and psychosomatic problems: A meta-analysis. Pediatrics, 132, 720–729.

Haivas, S., Hofmans, J., & Pepermans, R. (2012). Self-determination theory as a framework for exploring the impact of the organizational context on volunteer motivation: A study of Romanian volunteers. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 41, 1195–1214.

Hara, H. (2002). Justifications for bullying among Japanese schoolchildren. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 5, 197–204.

Hardy, S. A., Dollahite, D. C., Johnson, N., & Christensen, J. B. (2015). Adolescent motivations to engage in pro-social behaviors and abstain from health-risk behaviors: A self-determination theory approach. Journal of Personality, 83, 479–490.

Hoffman, M. L. (2000). Empathy and moral development. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hung, S.-Y., Durcikova, A., Lai, H.-M., & Lin, W.-M. (2011). The influence of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation on individuals’ knowledge sharing behavior. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 69, 415–427.

Hymel, S., McClure, R., Miller, M., Shumka, E., & Trach, J. (2015). Addressing school bullying: Insights from theories of group processes. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 37, 16–24.

Jones, S. E., Miller, J. D., & Lynam, D. R. (2011). Personality, antisocial behavior, and aggression: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Criminal Justice, 39, 329–337.

Jungert, T., Pioddi, B., & Thornberg, R. (2016). Early adolescents’ motivation to defend victims in school bullying and their perceptions of student–teacher relationships: A self-determination theory approach. Journal of Adolescence, 53, 75–90.

Kärnä, A., Voeten, M., Poskiparta, E., & Salmivalli, C. (2010). Vulnerable children in varying classroom contexts: Bystanders’ behaviors moderate the effects of risk factors on victimization. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 56, 261–282.

Kljakovic, M., & Hunt, C. (2016). A meta-analysis of predictors of bullying and victimisation in adolescence. Journal of Adolescence, 49, 134–145.

Kretschmer, T., Veenstra, R., Dekovic, M., & Oldenhinkel, A. J. (2017). Bullying development across adolescence, its antecedents, outcomes, and gender-specific patterns. Development and Psychopathology, 29, 941–955.

Kuppens, S., Grietens, H., Onghena, P., Michiels, D., & Subramanian, S. V. (2008). Individual and classroom variables associated with relational aggression in elementary-school aged children: A multilevel analysis. Journal of School Psychology, 46, 639–660.

Lerner, M. J. (1980). The belief in a just world: A fundamental delusion. New York, NY: Plenum.

Lodge, J., & Frydenberg, E. (2005). The role of peer bystanders in school bullying: Positive steps toward promoting peaceful schools. Theory into Practice, 44, 329–336.

Mitsopoulou, E., & Giovazolias, T. (2015). Personality traits, empathy and bullying behavior: A meta-analytic approach. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 21, 61–72.

Moran, C. M., Diefendorff, J. M., Kim, T., & Liu, Z. (2012). A profile approach to self-determination theory motivations at work. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 81, 354–363.

Moriarty, L. J. (2008). Controversies in victimology (2nd ed.). Newark, NJ: Matthew Bender & Company.

Ng, J. Y. Y., Ntoumanis, N., Thøgersen-Ntoumani, C., Deci, E. L., Ryan, R. M., Duda, J. L., et al. (2012). Self-determination theory applied to health contexts: A meta-analysis. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 7, 325–340.

Niemiec, C. P., & Ryan, R. M. (2009). Autonomy, competence, and relatedness in the classroom: Applying self-determination theory to educational practice. Theory and Research in Education, 7, 133–144.

Nocentini, A., Menesini, E., & Salmivalli, C. (2013). Level and change of bullying behavior during high school: A multilevel growth curve analysis. Journal of Adolescence, 36, 495–505.

Polanin, J. R., Espelage, D. L., & Pigott, T. D. (2012). A meta-analysis of school-based bullying prevention programs’ effects on bystander intervention behavior. School Psychology Review, 41, 47–65.

Poteat, V. P., & Vecho, O. (2016). Who intervenes against homophobic behavior? Attributes that distinguish active bystanders. Journal of School Psychology, 54, 17–28.

Reijntjes, A., Kamphuis, J. H., Prinzie, P., & Telch, M. J. (2010). Peer victimization and internalizing problems in children: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Child Abuse and Neglect, 34, 244–252.

Rigby, K. (2017). Bullying in Australian schools: The perceptions of victims and other students. Social Psychology of Education, 20, 589–600.

Rigby, K., & Bortolozzo, G. (2013). How schoolchildren’s acceptance of self and others relate to their attitudes to victims of bullying. Social Psychology of Education, 16, 181–197.

Ryan, R. M., & Connell, J. P. (1989). Perceived locus of causality and internalization: Examining reasons for acting in two domains. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 749–761.

Ryan, R. M., Patrick, H., Deci, E. L., & Williams, G. C. (2008). Facilitating health behaviour change and its maintenance: Interventions based on Self-Determination Theory. The European Health Psychologist, 10, 2–5.

Saarento, S., & Salmivalli, C. (2015). The role of classroom peer ecology and bystanders’ responses in bullying. Child Development Perspectives, 9, 201–205.

Salmivalli, C. (1999). Participant role approach to school bullying: Implications for interventions. Journal of Adolescence, 22, 453–459.

Salmivalli, C. (2010). Bullying and the peer group: A review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 15, 112–120.

Salmivalli, C., & Voeten, M. (2004). Connections between attitudes, group norms, and behaviour in bullying situations. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 23, 246–258.

Salmivalli, C., Voeten, M., & Poskiparta, E. (2011). Bystanders matter: Associations between reinforcing, defending, and the frequency of bullying behavior in classrooms. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 40, 668–676.

Smith, P. (2010). Bullying in primary and secondary schools: Psychological and organizational comparisons. In S. R. Jimersson, S. M. Swearer, & D. L. Espelage (Eds.), Handbook of bullying in schools: An international perspective (pp. 137–150). New York, NY: Routledge.

Staub, E. (2003). The psychology of good and evil: Why children, adults, and groups help and harm others. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sundel, M., & Sundel, S. S. (2005). Behavior change in the human services: Behavioral and cognitive principles and applications (5th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Swedish National Agency for Education. (2016). Attityder till skolan 2015 (Rapport 438). Stockholm: Wolters Kluwer.

Tani, F., Greenman, P. S., Schneider, B. H., & Fregoso, M. (2003). Bullying and the big five: A study of childhood personality and participant roles in bullying incidents. School Psychology International, 24, 131–146.

Taylor, G., Jungert, T., Mageau, G. A., Schattke, K., Dedic, H., Rosenfield, S., et al. (2014). A self-determination theory approach to predicting school achievement over time: The unique role of intrinsic motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 39, 342–358.

Thornberg, R. (2011). Young people’s representations of bullying causes. In M. Paludi (Ed.), The psychology of teen violence and victimization (Vol. 2, pp. 105–120). Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger.

Thornberg, R. (2015a). Motivation to defend bullying victim scale. Linköping: Linköping University.

Thornberg, R. (2015b). School bullying as a collective action: Stigma processes and identity struggling. Children & Society, 36, 310–320.

Thornberg, R. S. (2011). Bystander behavior in bullying situations: Basic moral sensitivity, moral disengagement and defender self-efficacy. Journal of Adolescence, 36, 475–483.

Thornberg, R., & Knutsen, S. (2011). Teenagers’ explanations of bullying. Child & Youth Care Forum, 40, 177–192.

Thornberg, R., & Jungert, T. (2013). Bystander behavior in bullying situations: Basic moral sensitivity, moral disengagement and defender self-efficacy. Journal of Adolescence, 36, 475–483.

Thornberg, R., & Jungert, T. (2014). School bullying and the mechanisms of moral disengagement. Aggressive Behavior, 40, 99–108.

Thornberg, R., Wänström, L., Hong, J. S., & Espelage, D. L. (2017). Classroom relationship qualities and social-cognitive correlates of defending and passive bystanding in school bullying in Sweden: A multilevel analysis. Journal of School Psychology, 63, 49–62.

Underwood, M. K. (2004). Gender and peer relations: Are the two gender cultures really all that different? In J. B. Kupersmidt & K. A. Dodge (Eds.), Children’s peer relations (pp. 21–36). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Volke, A. A., Dane, A., & Marini, Z. A. (2014). What is bullying? A theoretical redefinition. Developmental Review, 34, 327–343.

Weiner, B. (1995). Judgements of responsibility: A foundation for a theory of social conduct. New York, NY: Guilford.

Young-Jones, A., Fursa, S., Byrket, J. S., & Sly, J. S. (2015). Bullying affects more than feelings: The long-term implications of victimization on academic motivation in higher education. Social Psychology of Education, 18, 185–200.

Acknowledgements

This research was partially supported by a grant awarded to Robert Thornberg from The Swedish Research Council (Grant Number D0775301).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Thornberg, R., Wänström, L. Bullying and its association with altruism toward victims, blaming the victims, and classroom prevalence of bystander behaviors: a multilevel analysis. Soc Psychol Educ 21, 1133–1151 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-018-9457-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-018-9457-7