Abstract

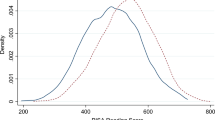

Countries’ education systems are often compared using academic achievement measures from large-scale assessments like PISA. These exercises are criticized because achievement is but one of the aims of education and comparisons don’t take into account each country’s socio-demographic composition, cultural and historical background and organizational features. We use data from OECD countries to assess countries that can serve as models for education policy to promote both high mathematics achievement and student well-being. We adopt a novel methodological approach based on imputation methods to simultaneously estimate mathematics achievement and students’ sense of belonging while taking into account countries’ socio-demographic and organizational features. Results indicate that, in general, education systems have been able to organize and use their resources to promote either mathematics performance or student well-being, but not both simultaneously. The East Asian approach to education is successful in promoting student achievement in mathematics while Austria, Norway and Spain have greater success in promoting students’ sense of belonging.

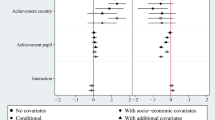

Source Own calculations based on PISA 2012 Database

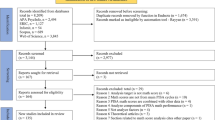

Source Own calculation based on PISA 2012 Database

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In Canada, the correlation between PISA reading scores and students’ actual grades in reading is 0.34 (the correlation between actual grades in mathematics and actual grades in reading is 0.38) (OECD 2010a: 78). The correlation between self-reported grades in reading and PISA reading scores ranges from 0.58 in Poland to 0.19 in the Flemish Community of Belgium, possibly reflecting different approaches to grading (OECD 2012b: 53).

By focusing only on mathematics scores, this paper may be arbitrarily reducing academic to mathematics as measured by PISA. It thus ignores achievement in reading or science (as well as that in other, non-measured domains). However, the latent correlation between mathematics and reading is 0.85 and between mathematics and science is 0.89 (OECD 2014: 230). As a result, adding reading and science scores to the analysis or running them separately for reading and science do not change the results presented. Grades in a particular could also be included, but they generally do not measure the same set of skills or attributes across countries (OECD 2012b).

The PISA 2012 Technical Report (OECD 2014) and the PISA Data Analysis Manual (OECD 2009a) suggest that, when computing estimates with standard errors, each estimate ought to be calculated separately based on each plausible value and then averaged to calculate the point estimate and combined to calculate both the population sampling and test item sampling error. In cases where standard errors are of no interest, the point estimate is obtained more efficiently by averaging the five plausible values and estimating the coefficient of interest on the basis of this average.

Full details on the assessment, sampling, design, rotation and scoring of PISA assessments can be found in the PISA 2012 Technical Report (OECD 2014).

Such is the logic of decomposition techniques to analyze the sources of differences in outcomes across groups. One such decomposition is the Oaxaca-Blinder decomposition (Barrera-Osorio et al. 2011).

Additionally, the difference between the two groups can include the interaction between assets and effects if the effect for a given asset becomes stronger as this asset becomes more or less prevalent. For the purposes of this study, we assume that there are no interactions between assets and effects, a likely assumption given the high percentage of variance explained in the models (see R2 columns in Tables S2 and S3) and the fact that for most of the assets measured in PISA there is already a restricted range given that schools and students are sampled, and that schools and students around the world share many attributes (Benavot et al. 1991; Boli et al. 1985; Meyer et al. 1992).

A preliminary step was performed to correct for missing data, see paragraph below on missing data in this section. This step thus draws on each country’s dataset with no missing data.

Although the imputation literature suggests the use of between 5 and 10 imputations (i.e. multiple imputation) to correctly and efficiently account for the uncertainty in imputation in the variance of the estimates (Allison 2002), we only impute once with the possibility of adding variability with Mark Chain Monte Carlo methods (i.e. stochastic imputation). Stochastic imputation is preferred over multiple imputation in our case because the latter is computationally intensive and the exploratory nature of this paper limits the need to produce unbiased standard errors yielded by multiple imputation.

A complete dataset is needed for our analyses to ensure that estimates for a country’s achievement and sense of belonging are based only on the country’s assets and only on the model country’s effects. If the country has missing data, the imputation procedure would use information from the model country to complete information about the country’s assets, thus biasing the country’s assets and the subsequent estimates for achievement and sense of belonging. SAS’s PROC MI was used for this purpose. In both instances, SAS PROC MI is used with no specification on the range of possible imputed values.

Tables S2 and S3 in the supplementary materials provide the regression coefficients of the relationship between each independent variable and mathematics performance and sense of belonging. They give an indication of the way each asset is related to student outcomes in each of the model countries.

Using all OECD countries as potential models for each other shows that those omitted from the selection of potential countries do not become educational policy examples for the remaining countries (results available upon demand). Countries not chosen as potential models for this paper include Chile, Greece, Italy, Greece, Mexico and Portugal (vertically stratified); Denmark, Estonia, Iceland and Sweden (Nordic); Australia, Ireland New Zealand and the United Kingdom (Anglo-Saxon); Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Switzerland (highly stratified Saxon); and the Czech Republic, Hungary, the Slovak Republic and Slovenia (Eastern European). Israel and Turkey were not chosen as potential models as their educational systems do not fall neatly into one of the six abovementioned types of education systems. In full models only Iceland becomes a model for sense of belonging in 16 countries, but the particular characteristics of this country make its characteristics potentially harder to replicate elsewhere (e.g. a total of only 204 schools for students in compulsory education).

The exploratory nature of this paper reduces the need for standard errors, thus reducing the need for more than one imputation, as is the case in multiple imputation. More than one imputation would greatly increase the computational demands of this analysis without any major improvement in the estimation of point estimates.

Tables S2 and S3 in the supplementary materials show the results of the simultaneous estimation for average mathematics achievement and sense of belonging, for all pairs of OECD and model countries. They also provide a fit of the models for each country. On average across OECD countries, the variables included in the analyses account for 69% of the variance in student mathematics achievement and 36% of the variance in students’ index of sense of belonging. Explained variance is relatively similar across OECD countries, indicating that the model proposed and used for the estimation of hypothetical scores is adequate.

References

Allison, P. (2002). Missing data. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Baker, D., & LeTendre, G. (2005). National differences, global similarities: World culture and the future of schooling. Stanford: Stanford Social Sciences.

Barrera-Osorio, F., Garcia-Moreno, V., Patrinos, H., & Porta, E. E. (2011). Using the oaxaca-blinder decomposition technique to analyze learning outcomes changes over time: An application to Indonesia’s results in PISA mathematics. In World Bank Policy research working paper series, 5584.

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117, 497–529.

Becker, B. E., & Luthar, S. S. (2002). Social-emotional factors affecting achievement outcomes among disadvantaged students: Closing the achievement gap. Educational Psychologist, 37(4), 197–214.

Benavot, A., Cha, Y. K., Kamens, D., Meyer, J. W., & Wong, S. Y. (1991). Knowledge for the masses—World models and national curricula, 1920–1986. American Sociological Review, 56(1), 85–100.

Boli, J., Ramirez, F. O., & Meyer, J. W. (1985). Explaining the origins and expansion of mass education. Comparative Education Review, 29(2), 145–170.

Buchmann, C. (2011). Frontiers in comparative and international sociology of education: American distinctiveness and global diversity. In M. Hallinan (Ed.), Frontiers in sociology of education (pp. 35–51). New York: Springer.

CAE - Conseil d’Analyse Économique. (2011). Évaluer la Performance Économique, le Bien-Être et la Soutenabilité. Paris: La Documentation Française.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1991). A motivational approach to self: Integration in personality. In R. Dienstbier (Ed.), Nebraska symposium on motivation: Perspectives on motivation (Vol. 38, pp. 237–288). Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Dupriez, V., Dumay, X., & Vause, A. (2008). How do school systems manage pupils’ heterogeneity? Comparative Education Review, 52(2), 245–273.

Goodenow, C. (1992). Strengthening the links between educational psychology and the study of social contexts. Educational Psychologist, 27(2), 177–196.

Goodenow, C. (1993). Classroom belonging among early adolescent students: Relationships to motivation and achievement. Journal of Early Adolescence, 13, 21–43.

Hagerty, B. M. K., Lynch-Sauer, J., Patusky, K., Bouwsema, M., & Collier, P. (1992). Sense of belonging: A vital mental health concept. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 6, 172–177.

Institute of Medicine, National Academy of Sciences, & National Academy of Engineering. (2007). Rising above the gathering storm: Energizing and employing America for a brighter economic future. Washington: The National Academies Press.

Kerckhoff, A. C. (1995). Institutional arrangements and stratification processes in industrial societies. Annual Review of Sociology, 21, 323–347.

LeTendre, G., Hofer, B., & Shimizu, H. (2003). What is tracking? Cultural expectations in the United States, Germany, and Japan. American Educational Research Journal, 40(1), 43–89.

Levin, H. (2012). More than just test scores. Prospects, 42(3), 269–284.

Loveless, T. (2013). International tests are not all the same. The Brown Center Chalkboard, No. 1. Washington, DC: Brookings.

Loveless, T. (2014). PISA’s China problem continues: A response to Schleicher, Zhang and Tucker. The Brown Center Chalkboard, No. 50. Washington, DC: Brookings.

Maslow, A. (1954). Motivation and personality. New York: Harper & Row.

Meyer, H. et al. (2014). An open letter: To Andreas Schleicher, OECD, Paris, Global Policy Comment, http://www.globalpolicyjournal.com/blog/05/05/2014/open-letter-andreas-schleicher-oecd-paris. Reprinted as Meyer, H. et al. (2014). OECD and pisa tests are damaging education worldwide—Academics, The Guardian, http://www.theguardian.com/education/2014/may/06/oecd-pisa-tests-damaging-education-academics.

Meyer, J., Ramirez, F., & Soysal, Y. (1992). World expansion of mass education, 1870–1980. Sociology of Education, 65(2), 128–149.

Muñoz, J. (1918). Historia Elemental de la Pedagojía Chilena. Santiago: Casa Editorial Minerva.

Murray, H. A. (1938). Explorations in personality. New York: Oxford University Press.

OECD. (2009a). PISA data analysis manual: SAS (2nd ed.). Paris: OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2009b). Doing better for children. Paris: OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2010a). Pathways to success: How knowledge and skills at age 15 shape future lives in Canada. PISA: OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2010b). PISA 2009 results: What makes a school successful? Resources, policies and practices (Vol. IV). Paris: OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2011). Strong performers, successful reformers: Lessons from PISA for the United States. Paris: OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2012a). Learning beyond fifteen: Ten years after PISA. Paris: OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2012b). Grade expectations: How marks and education policies shape students’ ambitions. Paris: OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2012c). PISA 2012 assessment framework. Paris: OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2013a). OECD skills outlook 2013: First results from the survey of adult skills. Paris: OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2013b). PISA 2012 results: What students know and can do. Paris: OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2013c). PISA 2012 results: What makes a school successful? Resources, policies and practices. Paris: OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2013d). PISA 2012 results: Ready to learn, students’ engagement, drive and self-beliefs. Paris: OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2013e). PISA 2012 results: Equity through excellence, giving every student the chance to succeed. Paris: OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2014). PISA 2012 technical report. Paris: OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2017). PISA 2015 results (Volume III): Students' well-being. Paris: OECD Publishing. doi:10.1787/9789264273856-en.

Osterman, K. F. (2000). Students’ need for belonging in the school community. Review of Educational Research, 70, 323–367.

Rogers, C. (1951). Client-centered therapy: Its current practice, implications and theory. London: Constable.

Sahlberg, P. (2011). Finnish lessons. New York: Teachers College Press.

Schleicher, A. (2015). Attacks on Pisa are entirely unjustified. Times Education Supplement, https://www.tes.com/article.aspx?storycode=6345213.

Sheldon, K. M., Elliot, A. J., Kim, Y., & Kasser, T. (2001). What’s satisfying about satisfying events? Comparing ten candidate psychological needs. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80, 325–339.

Simola, H. (2005). The Finnish miracle of PISA: Historical and sociological remarks on teaching and teacher education. Comparative Education, 41(4), 455–470.

Stankov, L. (1999). Mining on the ‘No Man’s Land’ between intelligence and personality. In P. L. Ackerman, P. C. Kyllonen, & R. D. Roberts (Eds.), Learning and individual differences: Process, trait, and content determinants (pp. 315–338). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Sternberg, R. J. (1995). In search of the human mind. Orlando: Harcourt Brace.

Stewart, W. (2013). Is Pisa fundamentally flawed? Times Education Supplement, https://www.tes.com/article.aspx?storycode=6344672.

Stinson, D. W. (2004). Mathematics as ‘Gate-Keeper’: Three theoretical perspectives that aim toward empowering all children with a key to the gate. Mathematics Educator, 14(1), 8–18.

Tinto, V. (1975). Dropout from higher education: A theoretical synthesis of recent research. Review of Educational Research, 45(1), 89–125.

Vallerand, R. J. (1997). Toward a hierarchical model of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. In M. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (pp. 271–360). New York: Academic Press.

Winship, C., & Radbill, L. (1994). Sampling weights and regression analysis. Sociological Methods & Research, 23(2), 230–257.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Marilyn Achiron, Tommaso Agasisti and the anonymous reviewers for their insight that improved the quality of the manuscript. The analyses presented are based on publicly available PISA 2012 data (www.pisa.oecd.org). The responsibility for opinions expressed in this article rests solely with their authors, and publication does not constitute an endorsement by the International Labour Office or by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development of the opinions expressed in it.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Montt, G., Borgonovi, F. Combining Achievement and Well-Being in the Assessment of Education Systems. Soc Indic Res 138, 271–296 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-017-1644-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-017-1644-y